Chapter 9

I Get Around: Transportation

In This Chapter

Moving along with motion verbs

Moving along with motion verbs

Making your way through the airport

Making your way through the airport

Exploring public transportation

Exploring public transportation

Asking directions

Asking directions

As the Russian proverb has it, Yazyk do Kiyeva dovyedyot (ee-zihk dah kee-ee-vuh duh-vee-dyot), which translates as “Your tongue will lead you to Kiev,” and basically means, “Ask questions, and you’ll get anywhere.” This chapter gives you all the phrases you need to navigate your way through the transportation maze.

Understanding Verbs of Motion

Every language has a lot of words for things the speakers of that language know well. That’s why the Eskimos have 12 different words for snow. Russians have a lot of space to move around — maybe that’s why they have so many different verbs of motion.

Your choice of verb depends on many different factors and your intended message. To mention just a few factors, the choice depends on

Whether the motion is performed with a vehicle or without it

Whether the motion is performed with a vehicle or without it

Whether the motion indicates a regular, habitual motion

Whether the motion indicates a regular, habitual motion

Whether the motion takes place at the moment of speaking

Whether the motion takes place at the moment of speaking

Going by foot or vehicle habitually

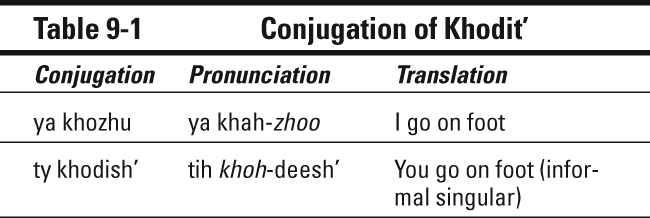

To indicate regular habitual motion in the present tense, you use the multidirectional verbs khodit’ (khah-deet’; to go on foot) and yezdit’ (yez-deet’; to go by vehicle). Think of places that you go to once a week, every day, two times a month, once a year, or every weekend. Most folks, for example, have to go to work every day. In Russian you say:

Ya khozhu na rabotu kazhdyj dyen’ (ya khah-zhoo nuh ruh-boh-too kahzh-dihy dyen’; I go to work every day) if you go by foot. (The verb khodit’ is conjugated in Table 9-1.)

Ya khozhu na rabotu kazhdyj dyen’ (ya khah-zhoo nuh ruh-boh-too kahzh-dihy dyen’; I go to work every day) if you go by foot. (The verb khodit’ is conjugated in Table 9-1.)

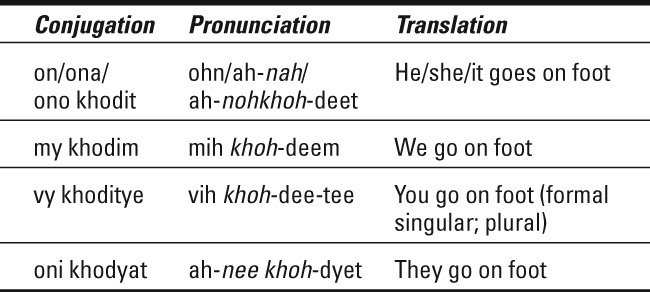

Ya yezzhu na rabotu kazhdyj dyen’ (ya yez-zhoo nuh ruh-boh–too kahzh-dihy dyen’; I go to work every day) if you go by vehicle. (The verb yezdit’ is conjugated in Table 9-2.)

Ya yezzhu na rabotu kazhdyj dyen’ (ya yez-zhoo nuh ruh-boh–too kahzh-dihy dyen’; I go to work every day) if you go by vehicle. (The verb yezdit’ is conjugated in Table 9-2.)

You also can specify the vehicle you’re using with one of these phrases:

yezdit’ na avtobusye (yez-deet’ nah uhf-toh-boo-see; to go by bus)

yezdit’ na avtobusye (yez-deet’ nah uhf-toh-boo-see; to go by bus)

yezdit’ na marshrutkye (yez-deet’ nah muhr-shroot-kee; to go by minivan)

yezdit’ na marshrutkye (yez-deet’ nah muhr-shroot-kee; to go by minivan)

yezdit’ na mashinye (yiez-deet’ nah muh-shih-nee; to go by car)

yezdit’ na mashinye (yiez-deet’ nah muh-shih-nee; to go by car)

yezdit’ na myetro (yez-deet’ nah mee-troh; to go by metro)

yezdit’ na myetro (yez-deet’ nah mee-troh; to go by metro)

yezdit’ na poyezdye (yez-deet’ nah poh-yeez-dee; to go by train)

yezdit’ na poyezdye (yez-deet’ nah poh-yeez-dee; to go by train)

yezdit’ na taksi (yez-deet’ nah tuhk-see; to go by taxi)

yezdit’ na taksi (yez-deet’ nah tuhk-see; to go by taxi)

Going by foot or vehicle at the present time

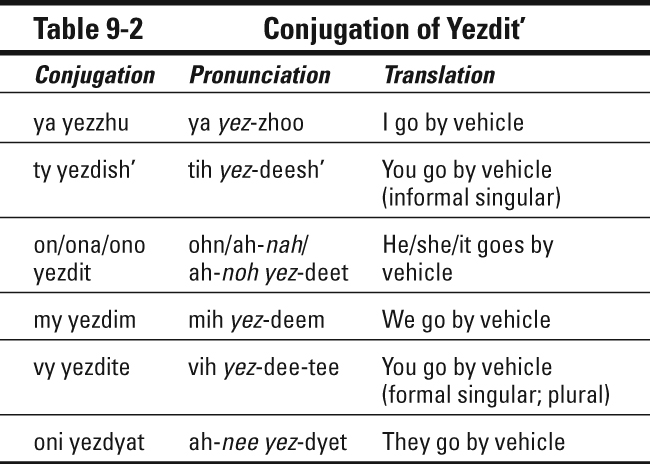

You use different verbs (called unidirectional verbs) to specify that you’re moving in a specific direction or to a specific place. You also use these verbs to indicate motion performed at the present moment.

For walking, use the verb idti (ee-tee; to go in one direction by foot), such as in the phrase Ya idu na rabotu (ya ee-doo nuh ruh-boh-too; I am walking to work). The verb idti is conjugated in Table 9-3.

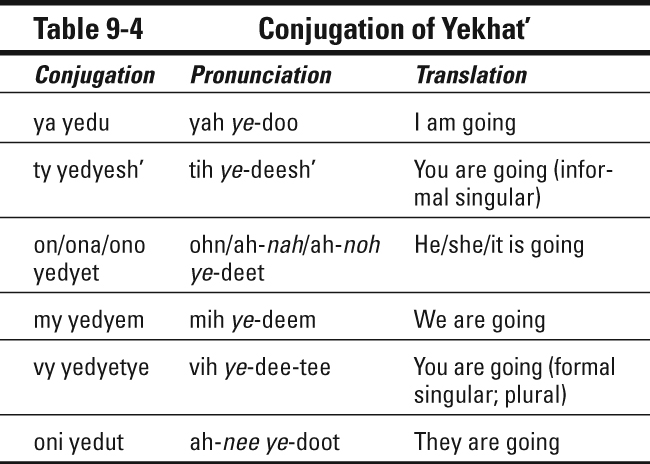

For moving by a vehicle, use the unidirectional verb yekhat’ (ye-khaht’; to go in one direction by a vehicle). The verb yekhat’ is conjugated in Table 9-4.

Explaining where you’re going

To tell where you’re going specifically, use the prepositions v (v; to) or na (nah; to) + the accusative case of the place you’re going:

Ya idu v tyeatr. (ya ee-doo f tee-ahtr; I am going to the theater.)

Ya idu v tyeatr. (ya ee-doo f tee-ahtr; I am going to the theater.)

Ona idyot na kontsyert. (ah-nah ee-dyot nuh kahn-tsehrt; She is going to the concert.)

Ona idyot na kontsyert. (ah-nah ee-dyot nuh kahn-tsehrt; She is going to the concert.)

For walking or driving around a place, use the preposition po (pah; around) + the dative case. (For more information on cases, see Chapter 2.)

Ona khodit po Moskvye. (ah-nah khoh-deet puh mahsk-vye; She walks around Moscow.)

Ona khodit po Moskvye. (ah-nah khoh-deet puh mahsk-vye; She walks around Moscow.)

My yezdim po tsyentru goroda. (mih yez-deem pah tsehnt-roo goh-ruh-duh; We drive around downtown.)

My yezdim po tsyentru goroda. (mih yez-deem pah tsehnt-roo goh-ruh-duh; We drive around downtown.)

.jpg)

Navigating the Airport

The vocabulary in this section helps you plan and enjoy your trip by samolyot (suh-mah-lyot; plane).

You use a special verb of motion when you talk about flying: lyetyet’ (lee-tyet’; to fly). You can’t use the verb yekhat’ when you talk about traveling by plane, unless the plane is wheeling around the airport without actually leaving the ground. If the plane actually takes off, you have to use the verb lyetyet’.

Checking in and boarding your flight

When you arrive at the aeroport (ah-eh-rah-pohrt; airport), the following words will help you navigate:

bilyet (bee-lyet; ticket)

bilyet (bee-lyet; ticket)

informatsionnoye tablo (een-fuhr-muh-tsih-oh-nuh-ye tahb-loh; departures and arrivals display)

informatsionnoye tablo (een-fuhr-muh-tsih-oh-nuh-ye tahb-loh; departures and arrivals display)

myesto u okna (myes-tuh oo ahk-nah; window seat)

myesto u okna (myes-tuh oo ahk-nah; window seat)

myesto u prokhoda (myes-tuh oo prah-khoh-duh; aisle seat)

myesto u prokhoda (myes-tuh oo prah-khoh-duh; aisle seat)

myetalloiskatyel’ (mee-tah-luh-ees-kah-teel’; metal detector)

myetalloiskatyel’ (mee-tah-luh-ees-kah-teel’; metal detector)

nomyer ryejsa (noh-meer ryey-suh; flight number)

nomyer ryejsa (noh-meer ryey-suh; flight number)

otpravlyeniye (uht-pruhv-lye-nee-eh; departures)

otpravlyeniye (uht-pruhv-lye-nee-eh; departures)

pasport (pahs-puhrt; passport)

pasport (pahs-puhrt; passport)

posadochnyj talon (pah-sah-duhch-nihy tuh-lohn; boarding pass)

posadochnyj talon (pah-sah-duhch-nihy tuh-lohn; boarding pass)

pribytiye (pree-bih-tee-eh; arrivals)

pribytiye (pree-bih-tee-eh; arrivals)

ruchnoj bagazh (rooch-nohy buh-gahsh; carryon)

ruchnoj bagazh (rooch-nohy buh-gahsh; carryon)

ryegistratsiya (ree-geest-rah-tsih-ye; check-in)

ryegistratsiya (ree-geest-rah-tsih-ye; check-in)

sluzhba byezopasnosti (sloozh-buh bee-zah-pahs-nuhs-tee; security service)

sluzhba byezopasnosti (sloozh-buh bee-zah-pahs-nuhs-tee; security service)

Here are some questions you may hear or ask as you check in:

Vy budyetye sdavat’ bagazh? (vih boo-dee-tee zdah-vaht’ buh-gahsh?; Are you checking any luggage?)

Vy budyetye sdavat’ bagazh? (vih boo-dee-tee zdah-vaht’ buh-gahsh?; Are you checking any luggage?)

Vy ostavlyali vash bagazh byez prismotra? (vih ahs-tahv-lya-lee vahsh buh-gahsh byes pree-smoh-truh?; Have you left your luggage unattended?)

Vy ostavlyali vash bagazh byez prismotra? (vih ahs-tahv-lya-lee vahsh buh-gahsh byes pree-smoh-truh?; Have you left your luggage unattended?)

Kakoj u myenya nomyer vykhoda? (kuh-kohy oo mee-nya noh-meer vih-khuh-duh?; What’s my gate number?)

Kakoj u myenya nomyer vykhoda? (kuh-kohy oo mee-nya noh-meer vih-khuh-duh?; What’s my gate number?)

Eto ryejs v . . . ? (eh-tuh ryeys v . . . ?; Is this the flight to . . . ?)

Eto ryejs v . . . ? (eh-tuh ryeys v . . . ?; Is this the flight to . . . ?)

Handling passport control and Customs

After leaving the plane and walking through a corridor maze, you see a crowded hall with pasportnyj kontrol’ (pahs-puhrt-nihy kahnt-rohl’; passport control). Make sure you get into the right line: One line is for grazhdanye Rossii (grahzh-duh-nee rah-see-ee; Russian citizens), and one is for inostranniye grazhdanye (ee-nahs-trah-nih-ee grahzh-duh-nee; foreign citizens).

At passport control, you show your pasport (pahs-puhrt; passport) and viza (vee-zah; visa). A pogranichnik (puhg-ruh-neech-neek; border official) asks you Tsyel’ priyezda? (tsehl’ pree-yez-duh; The purpose of your visit?) You may answer:

chastnyj vizit (chahs-nihy vee-zeet; private visit)

chastnyj vizit (chahs-nihy vee-zeet; private visit)

rabota (ruh-boh-tuh; work)

rabota (ruh-boh-tuh; work)

turizm (too-reezm; tourism)

turizm (too-reezm; tourism)

uchyoba (oo-choh-buh; studies)

uchyoba (oo-choh-buh; studies)

After you pick up your bagazh, the next step is going through tamozhyennyj dosmotr (tuh-moh-zhih-nihy dahs-mohtr; Customs). The best way to go is zyelyonyj koridor (zee-lyo-nihy kuh-ree-dohr; nothing to declare passage way [literally: green corridor]). Otherwise, you have to deal with tamozhyenniki (tuh-moh-zhih-nee-kee; Customs officers) and answer the question Chto dyeklariruyete? (shtoh deek-luh-ree-roo-ee-tee; What would you like to declare?)

To answer, say Ya dyeklariruyu . . . (ya deek-luh-ree-roo-yu; I’m declaring . . .) + the word for what you are declaring in the accusative case. The following items usually need to be declared:

alkogol’ (uhl-kah-gohl’; alcohol)

alkogol’ (uhl-kah-gohl’; alcohol)

dragotsyennosti (druh-gah-tseh-nuhs-tee; jewelry)

dragotsyennosti (druh-gah-tseh-nuhs-tee; jewelry)

proizvyedyeniya iskusstva (pruh-eez-vee-dye-nee-ye ees-koost-vuh; works of art)

proizvyedyeniya iskusstva (pruh-eez-vee-dye-nee-ye ees-koost-vuh; works of art)

Conquering Public Transportation

Russians hop around their humongous cities with butterfly ease, changing two to three means of public transportation during a one-way trip to work. And so can you. You just need to know where to look for the information and how to ask the right questions, which you discover in the following sections.

Taking a taxi

vash adryes (vahsh ahd-rees; your address)

vash adryes (vahsh ahd-rees; your address)

Kuda yedyetye? (koo-dah ye-dee-tee; Where are you going?)

Kuda yedyetye? (koo-dah ye-dee-tee; Where are you going?)

You can ask for your fare while you’re ordering your cab: Skol’ko eto budyet stoit’? (skohl’-kuh eh-tuh boo-deet stoh-eet’?; How much would that be?) This fare is usually nonnegotiable. If you hail a cab in the street, however, you have plenty of room for negotiating.

Using minivans

Marshrutki have different routes, marked by numbers. You can recognize a marshrutka by a piece of paper with its number in the front window. To board a marshrutka, you need to go to a place where it stops. These places aren’t usually marked, so you need to ask a local Gdye ostanavlivayutsya marshrutki? (gdye uhs-tuh-nahv-lee-vuh-yut-sye muhr-shroot-kee?; Where do the minivans stop?)

Catching buses, trolley buses, and trams

The first difficulty with all this variety of Russian public transportation is that, in English, all these things are called “buses.” Here’s a short comprehensive guide on how to tell one item from another:

avtobus (uhf-toh-boos): A bus as you know it

avtobus (uhf-toh-boos): A bus as you know it

trollyejbus (trah-lyey-boos): A bus connected to electric wires above

trollyejbus (trah-lyey-boos): A bus connected to electric wires above

tramvaj (truhm-vahy): A bus connected to electric wires and running on rails

tramvaj (truhm-vahy): A bus connected to electric wires and running on rails

Unless you’re into orienteering, the best way to find your route is to ask the locals. Just ask these questions:

Kak mnye doyekhat’ do Krasnoj Plosh’adi? (kahk mnye dah-ye-khuht’ dah krahs-nuhy ploh-sh’ee-dee?; How can I get to the Red Square?)

Kak mnye doyekhat’ do Krasnoj Plosh’adi? (kahk mnye dah-ye-khuht’ dah krahs-nuhy ploh-sh’ee-dee?; How can I get to the Red Square?)

Etot avtobus idyot do Ermitazha? (eh-tuht uhf-toh-boos ee-dyot duh ehr-mee-tah-zhuh?; Will this bus take me to the Hermitage?)

Etot avtobus idyot do Ermitazha? (eh-tuht uhf-toh-boos ee-dyot duh ehr-mee-tah-zhuh?; Will this bus take me to the Hermitage?)

Gdye mozhno kupit’ bilyety? (gdye mohzh-nuh koo-peet’ bee-lye-tih?; Where can I buy tickets?)

Gdye mozhno kupit’ bilyety? (gdye mohzh-nuh koo-peet’ bee-lye-tih?; Where can I buy tickets?)

Hopping onto the subway

The Russian myetro (mee-troh; subway) is beautiful, clean, user-friendly, and cheap. It connects the most distant parts of such humongous cities as Moscow, and it’s impenetrable to traffic complications. During the day, trains come every two to three minutes. Unfortunately, it’s usually closed between 1:30 a.m. and 4:30 a.m. Around 4:30 a.m., you can easily locate a stantsiya myetro (stahn-tsee-ye meet-roh; subway station) on a Moscow street by a crowd of young people in clubbing clothes waiting for the myetro to open so they can go home.

To take the myetro, you need to buy a kartochka (kahr-tuhch-kuh; fare card) for any number of trips or a proyezdnoj (pruh-eez-nohy; pass). Both are available in the vyestibyul’ myetro (vees-tee-byul meet-roh; metro foyer).

Hopping on a train

Trains are a great way to travel. The types of trains, in the order of increasing price and quality, are

elyektrichka (eh-leek-treech-kuh; a suburban train)

elyektrichka (eh-leek-treech-kuh; a suburban train)

skorostnoj poyezd (skuh-rahs-nohy poh-ehst; a low-speed train)

skorostnoj poyezd (skuh-rahs-nohy poh-ehst; a low-speed train)

skoryj poyezd (skoh-rihy poh-ehst; a faster and more expensive train)

skoryj poyezd (skoh-rihy poh-ehst; a faster and more expensive train)

firmyennyj poyezd (feer-mee-nihy poh-eehst; a premium train [literally: company train])

firmyennyj poyezd (feer-mee-nihy poh-eehst; a premium train [literally: company train])

You can kupit’ bilyety (koo-peet’ bee-lye-tih; buy tickets) directly at the railway station, at a travel agency, or in a zhyelyeznodorozhnyye kassy (zhih-lyez-nuh-dah-rohzh-nih-ee kah-sih; railway ticket office).

You can start your dialogue with Mnye nuzhyen bilyet v (mnye noo-zheen bee-lyet v; I need a ticket to) + the name of the city you’re heading for, in the accusative case (see Chapter 2 for more on cases). The ticket salesperson will probably ask you the following questions:

Na kakoye chislo? (nuh kuh-koh-eh chees-loh?; For what date?)

Na kakoye chislo? (nuh kuh-koh-eh chees-loh?; For what date?)

Vam kupye ili platskart? (vahm koo-peh ee-lee pluhts-kahrt?; Would you like a compartment car or a reserved berth?)

Vam kupye ili platskart? (vahm koo-peh ee-lee pluhts-kahrt?; Would you like a compartment car or a reserved berth?)

V odnu storonu ili tuda i obratno? (v ahd-noo stoh-ruh-noo ee-lee too-dah ee ah-braht-nuh?; One way or round trip?)

V odnu storonu ili tuda i obratno? (v ahd-noo stoh-ruh-noo ee-lee too-dah ee ah-braht-nuh?; One way or round trip?)

You can also tell the ticket salesperson what kind of seat you prefer: vyerkhnyaya polka (vyerkh-nee-ye pohl-kuh; top fold-down bed) or nizhnyaya polka (neezh-nye-ye pohl-kuh; bottom fold-down bed). On elyektrichki (eh-leek-treech-kee; suburban trains), which don’t have fold-down beds, seats aren’t assigned.

Asking “Where” and “How” Questions

When in doubt, just ask! In the following sections you discover how to ask for directions with two simple words: where and how.

Where is it?

If “where” indicates location rather than direction of movement and you aren’t using the so-called verbs of motion (to go, to walk, to drive, and so on), use the word gdye (where).

If “where” indicates location rather than direction of movement and you aren’t using the so-called verbs of motion (to go, to walk, to drive, and so on), use the word gdye (where).

If “where” indicates direction of movement rather than location, or in other words is used in a sentence with verbs of motion (to go, to walk, to drive, and so on), use the word kuda (where).

If “where” indicates direction of movement rather than location, or in other words is used in a sentence with verbs of motion (to go, to walk, to drive, and so on), use the word kuda (where).

So if you’re inquiring about location or destination you can ask:

Gdye blizhayshaya ostanovka avtobusa? (gdye blee-zhahy-shuh-ye uhs-tuh-nohf-kuh uhf-toh-boo-suh?; Where is the nearest bus stop?)

Gdye bibliotyeka? (gdye beeb-lee-ah-tye-kuh?; Where is the library?)

But if you’re asking about direction, you ask:

Kuda idyot etot avtobus? (koo-dah ee-dyot eh-tuht uhf-toh-boos?; Where is this bus going?)

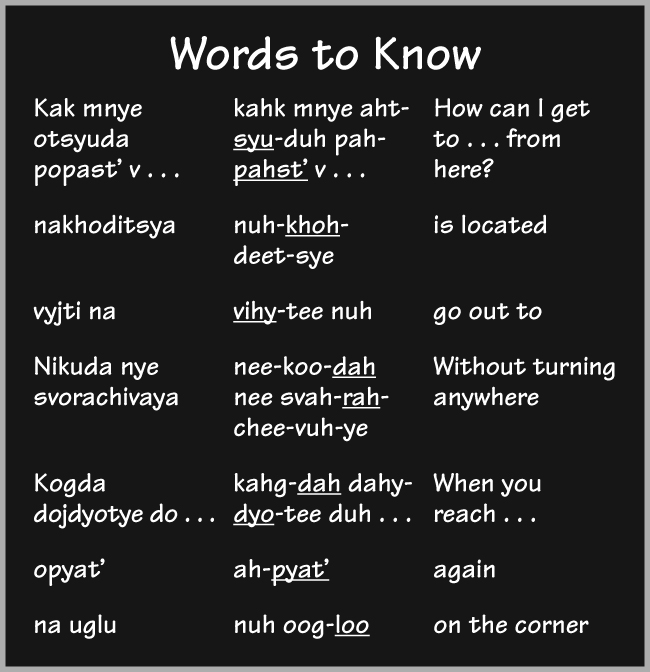

How do I get there?

Kak ya otsyuda mogu popast’ v muzyej? (kahk ya aht-syu-duh mah-goo pah-pahst’ v moo-zyey?; How do I get to the museum from here?)

Or you may want to make your question more impersonal by saying Kak otsyuda mozhno popast’ v (How does one get to . . . ?):

Kak otsyuda mozhno popast’ v muzyej? (kaht aht-syu-duh mohzh-nuh pah-pahst’ v moo-zyey?; How does one get to the museum from here?)

Understanding Specific Directions

When you’re done asking for directions, you need to understand what you’re being told. In the following sections, you find out about prepositions and other words people use when talking about directions in Russian.

Recognizing prepositions

Russian uses the same prepositions, v/na, to express both “to (a place)” and “in/at (a place).” When you use v/na to indicate movement, the noun indicating the place of destination takes the accusative case. If v/na is used to denote location, the noun denoting location is used in prepositional case. Compare these two sentences:

Ya idu v bibliotyeku. (ya ee-doo v beeb-lee-ah-tye-koo; I am going to the library.)

Ya idu v bibliotyeku. (ya ee-doo v beeb-lee-ah-tye-koo; I am going to the library.)

Ya v bibliotyekye. (ya v beeb-lee-ah-tye-kee; I am at the library.)

Ya v bibliotyekye. (ya v beeb-lee-ah-tye-kee; I am at the library.)

na lyektsiyu/na lyektsii (nuh lyek-tsih-yu/nuh lyek-tsih-ee; to a lecture/at a lecture)

na lyektsiyu/na lyektsii (nuh lyek-tsih-yu/nuh lyek-tsih-ee; to a lecture/at a lecture)

na stantsiyu/na stantsii (nuh stahn-tsih-yu/nuh stahn-tsih-ee; to a station/at a station)

na stantsiyu/na stantsii (nuh stahn-tsih-yu/nuh stahn-tsih-ee; to a station/at a station)

na urok/na urokye (nuh oo-rohk/nuh oo-roh-kee; to a class/at a class)

na urok/na urokye (nuh oo-rohk/nuh oo-roh-kee; to a class/at a class)

na vokzal/na vokzalye (nuh vahk-zahl/nuh vahk-zah-lee; to a railway station/at a railway station)

na vokzal/na vokzalye (nuh vahk-zahl/nuh vahk-zah-lee; to a railway station/at a railway station)

Some other prepositions that are helpful in directions are:

okolo (oh-kuh-luh; near) + a noun in the genitive case

okolo (oh-kuh-luh; near) + a noun in the genitive case

ryadom s (rya-duhm s; next to) + a noun in the instrumental case

ryadom s (rya-duhm s; next to) + a noun in the instrumental case

naprotiv (nuh-proh-teef; opposite, across from) + a noun in the genitive case

naprotiv (nuh-proh-teef; opposite, across from) + a noun in the genitive case

za (zah; behind, beyond) + a noun in the instrumental case

za (zah; behind, beyond) + a noun in the instrumental case

pozadi (puh-zuh-dee; behind) + a noun in the genitive case

pozadi (puh-zuh-dee; behind) + a noun in the genitive case

pyered (pye-reet; in front of) + a noun in the instrumental case

pyered (pye-reet; in front of) + a noun in the instrumental case

myezhdu (myezh-doo; between) + a noun in the instrumental case

myezhdu (myezh-doo; between) + a noun in the instrumental case

vnutri (vnoo-tree; inside) + a noun in the genitive case

vnutri (vnoo-tree; inside) + a noun in the genitive case

snaruzhi (snuh-roo-zhih; outside) + a noun in the genitive case

snaruzhi (snuh-roo-zhih; outside) + a noun in the genitive case

nad (naht; above) + a noun in the instrumental case

nad (naht; above) + a noun in the instrumental case

pod (poht; below) + a noun in the instrumental case

pod (poht; below) + a noun in the instrumental case

Keeping “right” and “left” straight

When people give you directions, they also often use these words:

sprava ot (sprah-vuh uht; to the right of) + a noun in the genitive case

sprava ot (sprah-vuh uht; to the right of) + a noun in the genitive case

napravo (nuh-prah-vuh; to the right)

napravo (nuh-prah-vuh; to the right)

slyeva ot (slye-vuh uht; to the left of) + a noun in the genitive case

slyeva ot (slye-vuh uht; to the left of) + a noun in the genitive case

nalyevo (nuh-lye-vuh; to the left)

nalyevo (nuh-lye-vuh; to the left)

na lyevoj storonye (nuh lye-vuhy stuh-rah-nye; on the left side)

na lyevoj storonye (nuh lye-vuhy stuh-rah-nye; on the left side)

na pravoj storonye (nuh prah-vahy stuh-rah-nye; on the right side)

na pravoj storonye (nuh prah-vahy stuh-rah-nye; on the right side)

Here’s a short exchange that may take place between you and a friendly-looking Russian woman:

You: Izvinitye, gdye magazin? (eez-vee-nee-tee gdye muh-guh-zeen?; Excuse me, where is the store?)

The woman: Magazin sprava ot aptyeki. (muh-guh-zeen sprah-vuh uht uhp-tye-kee; The store is to the right of the pharmacy.)

Making sense of commands

Here are some useful phrases in the imperative mood you may hear or want to use when giving directions:

Iditye praymo. (ee-dee-tee prya-muh; Go straight.)

Iditye praymo. (ee-dee-tee prya-muh; Go straight.)

Iditye nazad. (ee-dee-tee nuh-zaht; Go back.)

Iditye nazad. (ee-dee-tee nuh-zaht; Go back.)

Iditye pryamo do . . . (ee-dee-tee prya-muh duh; Go as far as . . .) + the noun in the genitive case

Iditye pryamo do . . . (ee-dee-tee prya-muh duh; Go as far as . . .) + the noun in the genitive case

Podojditye k . . . (puh-duhy-dee-tee k; Go up to . . .) + the noun in the dative case

Podojditye k . . . (puh-duhy-dee-tee k; Go up to . . .) + the noun in the dative case

Iditye po . . . (ee-dee-tee puh; Go down along . . .) + the noun in the dative case

Iditye po . . . (ee-dee-tee puh; Go down along . . .) + the noun in the dative case

Iditye mimo . . . (ee-dee-tee mee-muh; Pass by . . .) + the noun in the genitive case

Iditye mimo . . . (ee-dee-tee mee-muh; Pass by . . .) + the noun in the genitive case

Povyernitye nalyevo! (puh-veer-nee-tee nuh-lye-vuh; Turn left or take a left turn.)

Povyernitye nalyevo! (puh-veer-nee-tee nuh-lye-vuh; Turn left or take a left turn.)

Povyernitye napravo! (puh-veer-nee-tee nuh-prah-vuh; Turn right or take a right turn.)

Povyernitye napravo! (puh-veer-nee-tee nuh-prah-vuh; Turn right or take a right turn.)

Zavyernitye za ugol! (zuh-veer-nee-tee zah-oo-guhl; Turn around the corner.)

Zavyernitye za ugol! (zuh-veer-nee-tee zah-oo-guhl; Turn around the corner.)

Pyeryejditye ulitsu! (pee-reey-dee-tee oo-leet-soo; Cross the street.)

Pyeryejditye ulitsu! (pee-reey-dee-tee oo-leet-soo; Cross the street.)

Pyeryejditye plosh’ad’! (pee-reey-dee-tee ploh-sh’uht’; Cross the square.)

Pyeryejditye plosh’ad’! (pee-reey-dee-tee ploh-sh’uht’; Cross the square.)

Pyeryejditye chyerez dorogu! (pee-reey-dee-tee cheh-reez dah-roh-goo; Cross the street/road.)

Pyeryejditye chyerez dorogu! (pee-reey-dee-tee cheh-reez dah-roh-goo; Cross the street/road.)

.jpg)

Describing Distances

Sometimes you don’t want detailed information about directions. You just want to know whether someplace is near or far and how long it takes to get there. Here are some helpful phrases:

Eto dalyeko? (eh-tuh duh-lee-koh?; Is it far away?)

Eto dalyeko? (eh-tuh duh-lee-koh?; Is it far away?)

Eto dovol’no dalyeko. Dvye ostanovki na tramvaye/avtobusye/trolyejbusye/myetro. (eh-tuh dah-vohl’-nuh duh-lee-koh. dvye uhs-tuh-nohf-kee nuh truhm-vahy-ee/uhf- toh-boo-see/trah-lyey-boo-see/meet-roh; That’s quite far away. Two stops by the tram/bus/trolleybus/metro.)

Eto dovol’no dalyeko. Dvye ostanovki na tramvaye/avtobusye/trolyejbusye/myetro. (eh-tuh dah-vohl’-nuh duh-lee-koh. dvye uhs-tuh-nohf-kee nuh truhm-vahy-ee/uhf- toh-boo-see/trah-lyey-boo-see/meet-roh; That’s quite far away. Two stops by the tram/bus/trolleybus/metro.)

Eto nedalyeko. Minut pyatnadtsat’ pyeshkom. (eh-tuh nee-duh-lee-koh. mee-noot peet-naht-suht peesh-kohm; It’s not far away. About fifteen minutes’ walk.)

Eto nedalyeko. Minut pyatnadtsat’ pyeshkom. (eh-tuh nee-duh-lee-koh. mee-noot peet-naht-suht peesh-kohm; It’s not far away. About fifteen minutes’ walk.)