Chapter 1

I Say It How? Speaking Russian

In This Chapter

Understanding the Russian alphabet

Understanding the Russian alphabet

Pronouncing words properly

Pronouncing words properly

Discovering popular expressions

Discovering popular expressions

Welcome to Russian! Whether you want to read a Russian menu, enjoy Russian music, or just chat it up with your Russian friends, this is the beginning of your journey. In this chapter, you get all the letters of the Russian alphabet, discover the basic rules of Russian pronunciation, and say some popular Russian expressions and idioms.

Looking at the Russian Alphabet

If you’re like most English speakers, you probably think that the Russian alphabet is the most challenging aspect of picking up the language. But not to worry. The Russian alphabet isn’t as hard as you think.

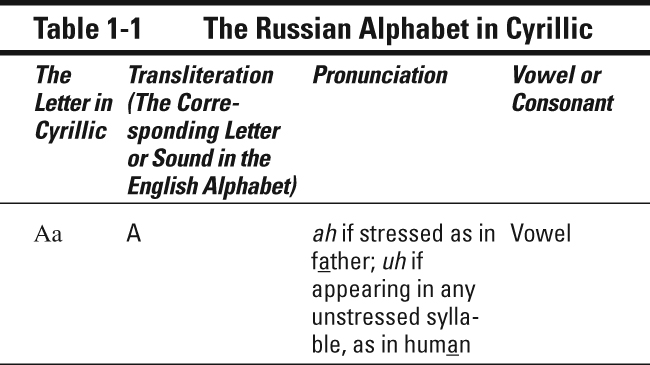

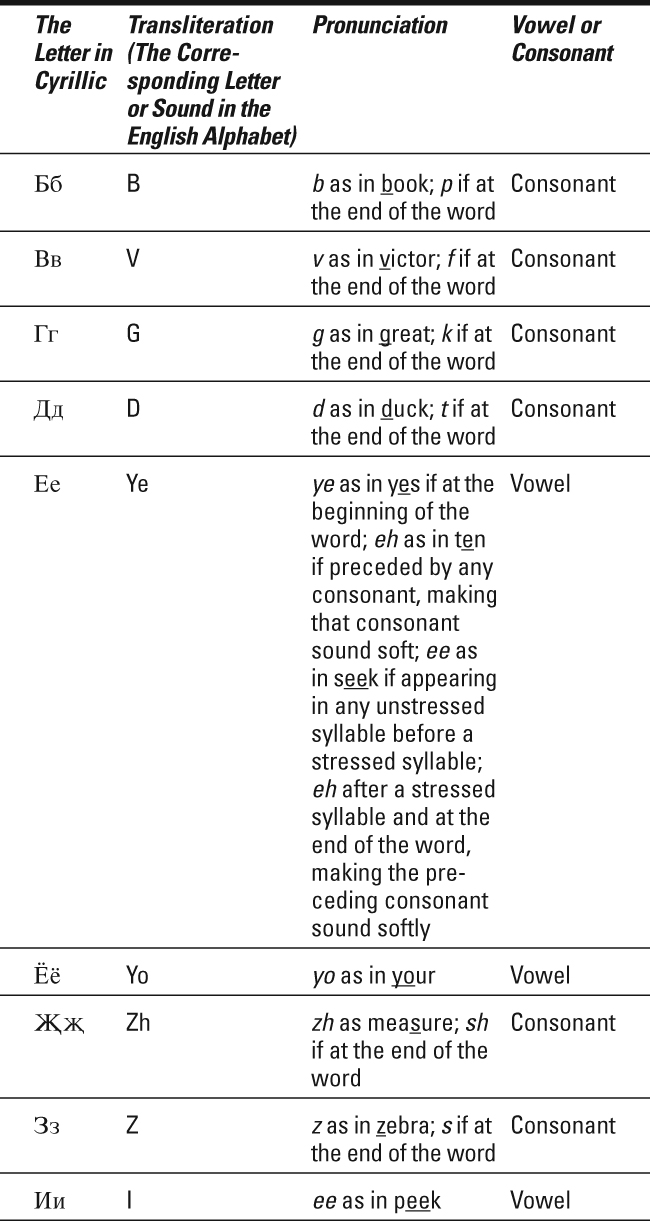

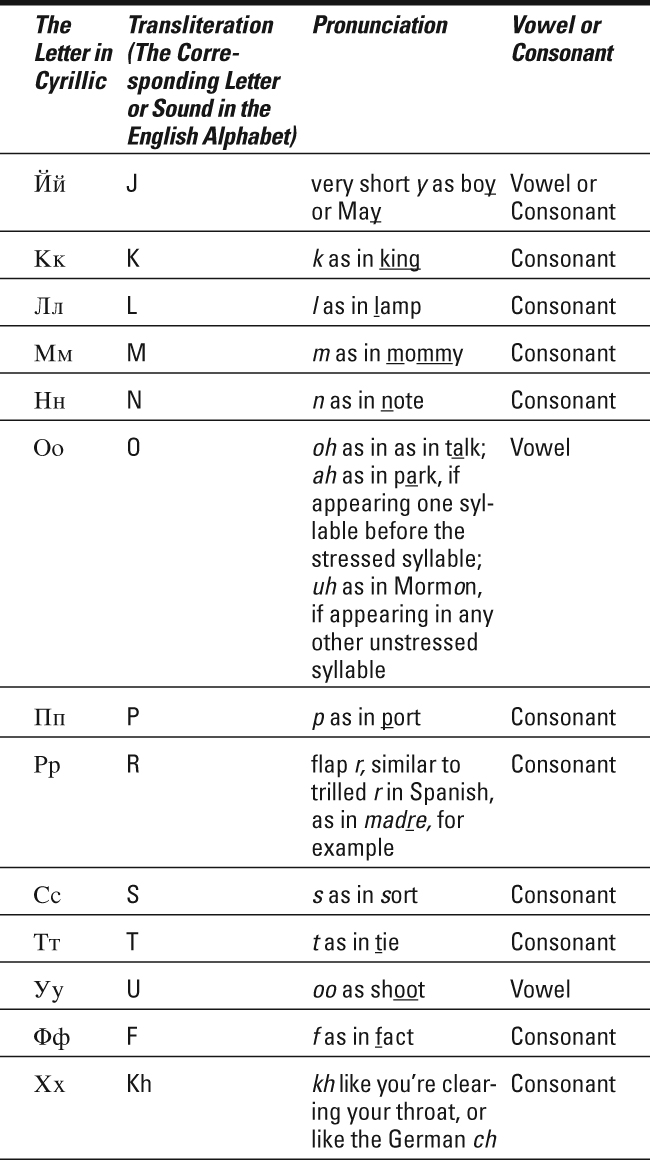

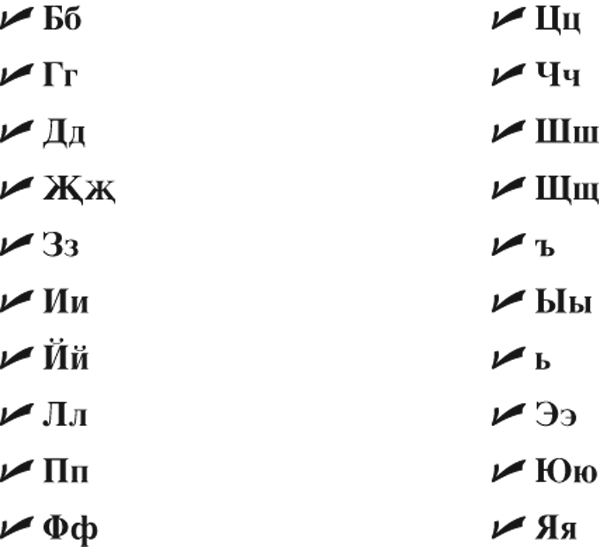

From A to Ya: Making sense of Cyrillic

The Russian alphabet is based on the Cyrillic alphabet, which was named after the ninth-century Byzantine monk, Cyril. But throughout this book, we convert all the letters into familiar Latin symbols, which are the same symbols we use in the English alphabet. This process of converting from Cyrillic to Latin letters is known as transliteration. We list the Cyrillic alphabet here in case you’re adventurous and brave enough to prefer reading real Russian instead of being fed with the ready-to-digest Latin version of it. And even if you don’t want to read the real Russian, check out Table 1-1 to find out what the whole fuss is about regarding the notorious “Russian alphabet.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

I know you! Familiar-looking, same-sounding letters

You may notice that some of the Russian letters in the previous section look a lot like English letters. The letters that look like English and are pronounced like English letters are

Whenever you read Russian text, you should be able to recognize and pronounce these letters right away.

Playing tricks: Familiar-looking, different-sounding letters

.jpg)

: It looks like English Bb, at least the capital letter does, but it’s pronounced like the sound v as in victor or vase.

: It looks like English Bb, at least the capital letter does, but it’s pronounced like the sound v as in victor or vase.

: This one’s a constant annoyance for English speakers, who want to pronounce it like ee, as in the English word geese. In Russian, it’s pronounced that way only if it appears in an unstressed syllable. Otherwise, if it appears in a stressed syllable, it is pronounced like ye as in yes.

: This one’s a constant annoyance for English speakers, who want to pronounce it like ee, as in the English word geese. In Russian, it’s pronounced that way only if it appears in an unstressed syllable. Otherwise, if it appears in a stressed syllable, it is pronounced like ye as in yes.

: Don’t confuse this with the letter Ee. When two dots appear over the Ee, it’s considered a different letter, and it’s pronounced like yo as in your.

: Don’t confuse this with the letter Ee. When two dots appear over the Ee, it’s considered a different letter, and it’s pronounced like yo as in your.

: It’s not the English Hh — it just looks like it. Actually, it’s pronounced like n as in nick.

: It’s not the English Hh — it just looks like it. Actually, it’s pronounced like n as in nick.

: In Russian it’s pronounced like a trilled r and not like the English letter p as in pick.

: In Russian it’s pronounced like a trilled r and not like the English letter p as in pick.

: This letter is always pronounced like s as in sun and never like k as in victor.

: This letter is always pronounced like s as in sun and never like k as in victor.

: This letter is pronounced like oo as in shoot and never like y as in yes.

: This letter is pronounced like oo as in shoot and never like y as in yes.

: Never pronounce this letter like z or ks as in the word Xerox. In Russian, the sound it represents is a coarse-sounding, guttural kh, similar to the German ch. (See “Surveying sticky sounds,” later in this chapter, for info on pronouncing this sound.)

: Never pronounce this letter like z or ks as in the word Xerox. In Russian, the sound it represents is a coarse-sounding, guttural kh, similar to the German ch. (See “Surveying sticky sounds,” later in this chapter, for info on pronouncing this sound.)

How bizarre: Weird-looking letters

As you’ve probably noticed, quite a few Russian letters don’t look like English letters at all:

You may recognize several of these weird letters, such as  , from learning the Greek alphabet during your fraternity or sorority days.

, from learning the Greek alphabet during your fraternity or sorority days.

Sounding Like a Real Russian with Proper Pronunciation

Compared to English pronunciation, which often has more exceptions than rules, Russian rules of pronunciation are fairly clear and consistent.

Understanding the one-letter/ one-sound principle

Giving voice to vowels

Vowels are the musical building blocks of every Russian word. If you flub a consonant or two, you’ll probably still be understood. But if you don’t pronounce your vowels correctly, there’s a good chance you won’t be understood at all. So it’s a good idea to get down the basic principles of saying Russian vowels.

That’s stretching it: Lengthening out vowels

Some stress is good: Accenting the right vowels

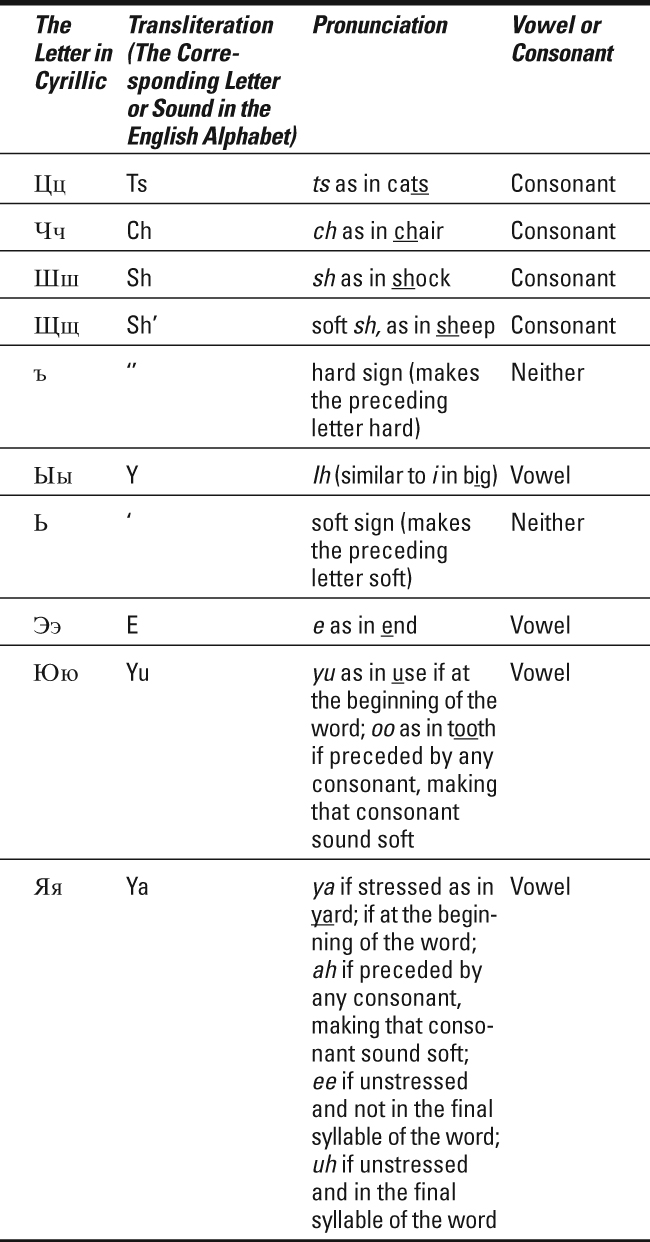

Vowels misbehavin’: Reduction

.jpg)

O, which is normally pronounced like oh, sounds like ah (like the letter a in the word father) if it occurs exactly one syllable before the stressed syllable, and like a neutral uh (like the letter a in the word about) if it appears in any other unstressed syllable.

O, which is normally pronounced like oh, sounds like ah (like the letter a in the word father) if it occurs exactly one syllable before the stressed syllable, and like a neutral uh (like the letter a in the word about) if it appears in any other unstressed syllable.

A, which is pronounced like ah when it’s stressed, is pronounced like a neutral uh (like the letter a in the word about) if it appears in any unstressed syllable.

A, which is pronounced like ah when it’s stressed, is pronounced like a neutral uh (like the letter a in the word about) if it appears in any unstressed syllable.

The honest-to-goodness truth is that when the letter a appears in the syllable preceding the stressed syllable, its pronunciation is somewhere between uh and ah. We don’t, however, want to burden you with excessive linguistic information, so we indicate the letter a as uh in all unstressed positions. Moreover, in conversational speech, catching the distinction is nearly impossible. If you say an unstressed a as uh, people will fully understand you.

Ye, which is pronounced like ye (as in yet) in a stressed syllable, sounds like ee (as in seek) in any unstressed syllable.

Ye, which is pronounced like ye (as in yet) in a stressed syllable, sounds like ee (as in seek) in any unstressed syllable.

When it appears at the end of a word, as in viditye (vee-dee-tee; [you] see [plural and formal singular]), or after another vowel, as in chayepitiye (chee-ee-pee-tee-eh; tea drinking), unstressed ye sounds like eh after another vowel at the end of the word.

An unstressed ya sounds either like ee (as in peek) if it’s unstressed (but not in the word’s final syllable) or like yuh if it’s unstressed in the final syllable of the word and also preceded by another vowel or ;; if it is preceded by a consonant, it is pronounced as uh and the preceding consonant is pronounced softly.

An unstressed ya sounds either like ee (as in peek) if it’s unstressed (but not in the word’s final syllable) or like yuh if it’s unstressed in the final syllable of the word and also preceded by another vowel or ;; if it is preceded by a consonant, it is pronounced as uh and the preceding consonant is pronounced softly.

Here are some examples of how vowel reduction affects word pronunciation:

You write Kolorado (Colorado) but say kuh-lah-rah-duh. Notice how the first o is reduced to a neutral uh and the next o is reduced to an ah sound (because it’s exactly one syllable before the stressed syllable), and it’s reduced again to a neutral uh sound in the final unstressed syllable.

You write Kolorado (Colorado) but say kuh-lah-rah-duh. Notice how the first o is reduced to a neutral uh and the next o is reduced to an ah sound (because it’s exactly one syllable before the stressed syllable), and it’s reduced again to a neutral uh sound in the final unstressed syllable.

You write khorosho (good, well) but say khuh-rah-shoh. Notice how the first o is reduced to a neutral uh, the next o is reduced to ah (it precedes the stressed syllable), and o in the last syllable is pronounced as oh because it’s stressed.

You write khorosho (good, well) but say khuh-rah-shoh. Notice how the first o is reduced to a neutral uh, the next o is reduced to ah (it precedes the stressed syllable), and o in the last syllable is pronounced as oh because it’s stressed.

You write napravo (to the right) but say nuh-prah-vuh. Notice that the first a is reduced to a neutral uh (because it’s not in the stressed syllable), the second a is pronounced normally (like ah) and the final o is pronounced like a neutral uh, because it follows the stressed syllable.

You write napravo (to the right) but say nuh-prah-vuh. Notice that the first a is reduced to a neutral uh (because it’s not in the stressed syllable), the second a is pronounced normally (like ah) and the final o is pronounced like a neutral uh, because it follows the stressed syllable.

You write Pyetyerburg (Petersburg) but say pee-teer-boork. Notice how ye is reduced to the sound ee in each case, because it’s not stressed.

You write Pyetyerburg (Petersburg) but say pee-teer-boork. Notice how ye is reduced to the sound ee in each case, because it’s not stressed.

You write Yaponiya (Japan) but say yee-poh-nee-uh. Notice how the unstressed letter ya sounds like yee at the beginning of the word and like ye at the end of the word (because it’s unstressed and in the final syllable).

You write Yaponiya (Japan) but say yee-poh-nee-uh. Notice how the unstressed letter ya sounds like yee at the beginning of the word and like ye at the end of the word (because it’s unstressed and in the final syllable).

Saying sibilants with vowels

The letters zh, ts, ch, sh, and sh’ are called sibilants, because they emit a hissing sound. When certain vowels appear after these letters, those vowels are pronounced slightly differently than normal. After a sibilant, ye is pronounced like eh (as in end) and yo is pronounced like oh (as in talk). Examples are the words tsyentr (tsehntr; center) and shyol (shohl; went by foot [masculine]). The sound ee always becomes ih after one of these sibilants, regardless of whether the ee sound comes from the letter i or from an unstressed ye before the stressed syllable. Take, for example, the words mashina (muh-shih-nuh; car) and shyestoy (shih-stohy; the sixth).

Enunciating consonants correctly

Like Russian vowels, Russian consonants follow certain patterns and rules of pronunciation. If you want to sound like a real Russian, you need to keep the basics in the following sections in mind.

Say it, don’t spray it! Relaxing with consonants

When pronouncing the letters p, t, or k, English speakers are used to straining their tongue and lips. This strain results in what linguists call aspiration — a burst of air that comes out of your mouth as you say these sounds. To see what we’re talking about, put your hand in front of your mouth and say the word top. You should feel air against your hand as you pronounce the word.

Cat got your tongue? Consonants losing their voice

Some consonants (b, v, g, d, zh, and z) are called voiced consonants because they’re pronounced with the voice. But when voiced consonants appear at the end of a word, they actually lose their voice. This process is called devoicing. They’re still spelled the same, but in their pronunciation, they transform into their devoiced counterparts:

B is pronounced like p.

B is pronounced like p.

V is pronounced like f.

V is pronounced like f.

G is pronounced like k.

G is pronounced like k.

D is pronounced like t.

D is pronounced like t.

Zh is pronounced like sh.

Zh is pronounced like sh.

Z is pronounced like s.

Z is pronounced like s.

Here are some examples:

You write Smirnov but pronounce it as smeer-nohf because v at the end of the word is pronounced like f.

You write Smirnov but pronounce it as smeer-nohf because v at the end of the word is pronounced like f.

You write garazh (garage) but say guh-rahsh, because at the end of the word, zh loses its voice and is pronounced like sh.

You write garazh (garage) but say guh-rahsh, because at the end of the word, zh loses its voice and is pronounced like sh.

Nutty clusters: Pronouncing consonant combinations

Russian speech often sounds like an endless flow of consonant clusters. Combinations of two, three, and even four consonants are quite common. Take, for example, the common word for hello in Russian — zdravstvujtye (zdrah-stvooy-teh), which has two difficult consonant combinations (zdr and stv). Or take the word for opinion in Russian — vzglyad (vzglyat). The word contains four consonants following one another: vzgl.

obstoyatyel’stvo (uhp-stah-ya-tehl’-stvuh; circumstance)

obstoyatyel’stvo (uhp-stah-ya-tehl’-stvuh; circumstance)

pozdravlyat’ (puh-zdruhv-lyat’; to congratulate)

pozdravlyat’ (puh-zdruhv-lyat’; to congratulate)

prestuplyeniye (pree-stoo-plyen-ee-ye; crime)

prestuplyeniye (pree-stoo-plyen-ee-ye; crime)

Rozhdyestvo (ruzh-deest-voh; Christmas)

Rozhdyestvo (ruzh-deest-voh; Christmas)

vzdor (vzdohr; nonsense)

vzdor (vzdohr; nonsense)

vzglyanut’ (vzglee-noot’; to look/glance)

vzglyanut’ (vzglee-noot’; to look/glance)

Surveying sticky sounds

Some Russian letters and sounds are hard for speakers of English. Take a look at some of them and find out how to pronounce them.

The bug sound zh

This sound corresponds to the letter  . It looks kind of like a bug, doesn’t it? It sounds like a bug, too! In pronouncing it, try to imitate the noise produced by a bug flying over your ear — zh-zh-zh . . . The sound is similar to the sound in the words pleasure or measure.

. It looks kind of like a bug, doesn’t it? It sounds like a bug, too! In pronouncing it, try to imitate the noise produced by a bug flying over your ear — zh-zh-zh . . . The sound is similar to the sound in the words pleasure or measure.

The very short i sound

This sound corresponds to the letter  . This letter’s name is i kratkoye, which literally means “a very short i,” but it actually sounds like the very short English y. This sound is what you hear when you say the word boy. You should notice your tongue touching the roof of your mouth when you say this sound.

. This letter’s name is i kratkoye, which literally means “a very short i,” but it actually sounds like the very short English y. This sound is what you hear when you say the word boy. You should notice your tongue touching the roof of your mouth when you say this sound.

The rolled sound r

This sound corresponds to the letter  in the Russian alphabet. To say it correctly, begin by saying an English r and notice that your tongue is rolled back. Now begin moving your tongue back, closer to your upper teeth and try to say this sound with your tongue in this new position. You’ll hear how the quality of the sound changes. This is the way the Russians say it.

in the Russian alphabet. To say it correctly, begin by saying an English r and notice that your tongue is rolled back. Now begin moving your tongue back, closer to your upper teeth and try to say this sound with your tongue in this new position. You’ll hear how the quality of the sound changes. This is the way the Russians say it.

The guttural sound kh

The corresponding Russian letter is  . To say it, imagine that you’re eating and a piece of food just got stuck in your throat. What’s the first reflex your body responds with? Correct! You will try to cough it up. Remember the sound your throat produces? This is the Russian sound kh. It’s similar to the German ch.

. To say it, imagine that you’re eating and a piece of food just got stuck in your throat. What’s the first reflex your body responds with? Correct! You will try to cough it up. Remember the sound your throat produces? This is the Russian sound kh. It’s similar to the German ch.

The revolting sound y

To say this sound correctly, imagine that you’re watching something really revolting, like an episode or Survivor, where the participants are gorging on a plate of swarming bugs. Now recall the sound you make in response to this. This sound is pronounced something like ih, and that’s how you pronounce the Russian

(the transliteration is y). Because this letter appears in some of the most commonly used words, including ty (tih; you [informal]), vy (vih; you [formal singular and plural]), and my (mih; we), it’s important to say it as best you can.

(the transliteration is y). Because this letter appears in some of the most commonly used words, including ty (tih; you [informal]), vy (vih; you [formal singular and plural]), and my (mih; we), it’s important to say it as best you can.

The hard sign

This is the letter  . Although the soft sign makes the preceding sound soft (see the next section), the hard sign makes it — yes, you guessed it — hard. The good news is that this letter (which transliterates to ”) is rarely ever used in contemporary Russian. And even when it is, it doesn’t change the pronunciation of the word. So, why does Russian have this sign? For two purposes:

. Although the soft sign makes the preceding sound soft (see the next section), the hard sign makes it — yes, you guessed it — hard. The good news is that this letter (which transliterates to ”) is rarely ever used in contemporary Russian. And even when it is, it doesn’t change the pronunciation of the word. So, why does Russian have this sign? For two purposes:

To harden the previous consonant

To harden the previous consonant

To retain the hardness of the consonant before the vowels ye, yo, yu, and ya, which must be pronounced like at the beginning of the word.

To retain the hardness of the consonant before the vowels ye, yo, yu, and ya, which must be pronounced like at the beginning of the word.

Without the hard sign, these consonants would normally palatalize (soften). When a hard sign = separates a consonant and one of these vowels, the consonant is pronounced without palatalization, as in the word pod”yezd (pahd-yezd; porch), for example. However, don’t worry too much about this one if your native language is English. Native speakers of English rarely tend to palatalize their Russian consonants the way Russians do it. In other words, if you’re a native English speaker and you come across the situation described here, you probably make your consonant hard and, therefore, pronounce it correctly by default!

The soft sign

This is the letter ; (transliterated to ’), and it doesn’t have a sound. Its only mission in life is to make the preceding consonant soft. This sound is very important in Russian because it can change the meaning of a word. For example, without the soft sign, the word mat’ (maht’; mother) becomes mat, which means “obscene language.” And when you add a soft sign at the end of the word von (vohn; over there), it becomes von’ (vohn’) and means “stench.” See how important the soft sign is?

It is also used retain the softness of the consonant before the vowels ye, yo, yu, and ya, which must be pronounced as at the beginning of the word — for example, v’yuga (v’yoo-guh; blizzard). Another very important function of  is that it shows the grammatical gender (feminine) if it follows a sibilant at the end of the word; in this case,

is that it shows the grammatical gender (feminine) if it follows a sibilant at the end of the word; in this case,  does not affect pronunciation. Compare myech (mehch; sword [masculine]) and noch’ (nohch; night [feminine]).

does not affect pronunciation. Compare myech (mehch; sword [masculine]) and noch’ (nohch; night [feminine]).

So, here’s how you can make consonants soft:

1. Say the consonant — for example, l, t, or d.

Note where your tongue is. What you should feel is that the tip of your tongue is touching the ridge of your upper teeth and the rest of the tongue is hanging in the mouth like a hammock in the garden on a nice summer day.

2. While you’re still pronouncing the consonant, raise the body of your tongue and press it against the hard palate.

Can you hear how the quality of the consonant has changed? It sounds much softer now, doesn’t it? That’s how you make your consonants soft.

, which is transcribed as ‘ but only softens the preceding consonant.

, which is transcribed as ‘ but only softens the preceding consonant. . These letters (ye, yo, ya, and yu) preserve the y sound if they are at the beginning of the word (as in yes, your, yard, and youth).

. These letters (ye, yo, ya, and yu) preserve the y sound if they are at the beginning of the word (as in yes, your, yard, and youth). (zah-muhk; castle) is written za’mok, and zamok (zuh-mohk; lock) is written

(zah-muhk; castle) is written za’mok, and zamok (zuh-mohk; lock) is written  .

.