Chapter 2

Grammar on a Diet: Just the Basics

In This Chapter

Understanding the Russian case system

Understanding the Russian case system

Using nouns, pronouns, and adjectives

Using nouns, pronouns, and adjectives

Forming verbs in different tenses

Forming verbs in different tenses

One of the biggest differences between English and Russian is that English tends to have a fixed order of words, whereas Russian enjoys a free order of words.

In English, word order can often determine the meaning of a sentence. For example, in English you say, “The doctor operated on the patient,” but you never say, “The patient operated on the doctor.” It just doesn’t make sense.

In Russian, you can freely shift around the order of words in a sentence, because the Russian case system tells you exactly what role each word plays in the sentence. What’s a case? Read on.

Making the Russian Cases

Nominative case

A noun (or a pronoun or an adjective) always appears in the nominative case in an English-Russian dictionary. Its main function is to indicate the subject of the sentence. For example, in the sentence Bryenda izuchayet russkij yazyk (brehn-duh ee-zoo-chah-eht roos-keey yee-zihk; Brenda studies Russian), the word Bryenda, is the subject of the sentence and consequently is used in the nominative case.

Genitive case

Use the genitive case to indicate possession. It answers the question “Whose?” In the phrase kniga Anny (knee-guh ah-nih; Anna’s book), Anna is in the genitive case (Anny) because she’s the book’s owner.

Accusative case

The accusative case mainly indicates a direct object, which is the object of the action of the verb in a sentence. For example, in the sentence Ya lyublyu russkij yazyk (yah l’oou-bl’oo roo-skeey yee-zihk; I love Russian), the phrase russkij yazyk is in the accusative case because it’s the direct object.

Dative case

Use the dative case to indicate an indirect object, which is the person or thing toward whom the action in a sentence is directed. For example, in the sentence Ya dal uchityelyu sochinyeniye (yah dahl oo-chee-tee-lyu suh-chee-n’eh-nee-eh; I gave the teacher my essay), uchityelyu (oo-chee-tee-lyu; teacher) is in the dative case because it’s the indirect object.

Use the dative case after certain prepositions such as k (k; toward) and po (poh; along).

Instrumental case

As the name suggests, the instrumental case is often used to indicate the instrument that assists in the carrying out of an action. So, when you say that you’re writing a letter with a ruchka (rooch-kuh; pen), you have to put ruchka into the instrumental case, which is ruchkoj (rooch-kuhy).

Use the instrumental case after certain prepositions such as s (s; with), myezhdu (m’ehzh-doo; between), nad (naht; over), pod (poht; below), and pyeryed (p’eh-reet; in front of).

Prepositional case

Only used after certain prepositions. Older Russian textbooks often refer to it as the locative case, because it often indicates the location where the action takes place. It’s used with the prepositions v (v; in), na (nah; on), o (oh; about), and ob (ohb; about).

Building Your Grammar Base with Nouns and Pronouns

Nouns and pronouns are the building blocks of any sentence. In the following sections, you find out about genders, cases, and plurals of nouns.

Getting the lowdown on the gender of nouns

Unlike English nouns, every Russian noun has what’s called a grammatical gender: masculine, feminine, or neuter. Knowing a noun’s gender is important because it determines how the noun changes for each of the six cases.

The ending of a noun in its dictionary form (the nominative case) indicates the noun’s gender in most cases. Nouns ending in a consonant and j (an unusual letter) are masculine. Nouns ending in a or ya are feminine. If nouns end in o, ye, or yo, they are neuter. Nouns can be either feminine or masculine if they end in the soft sign (’).

Grammatical gender for words denoting living beings, in the majority of cases, coincides with biological gender. The word mal’chik (mahl’-cheek; boy) is a masculine noun and the word dyevushka (d’eh-voosh-kuh; girl) is a feminine noun, just as you’d expect.

Checking out cases for nouns

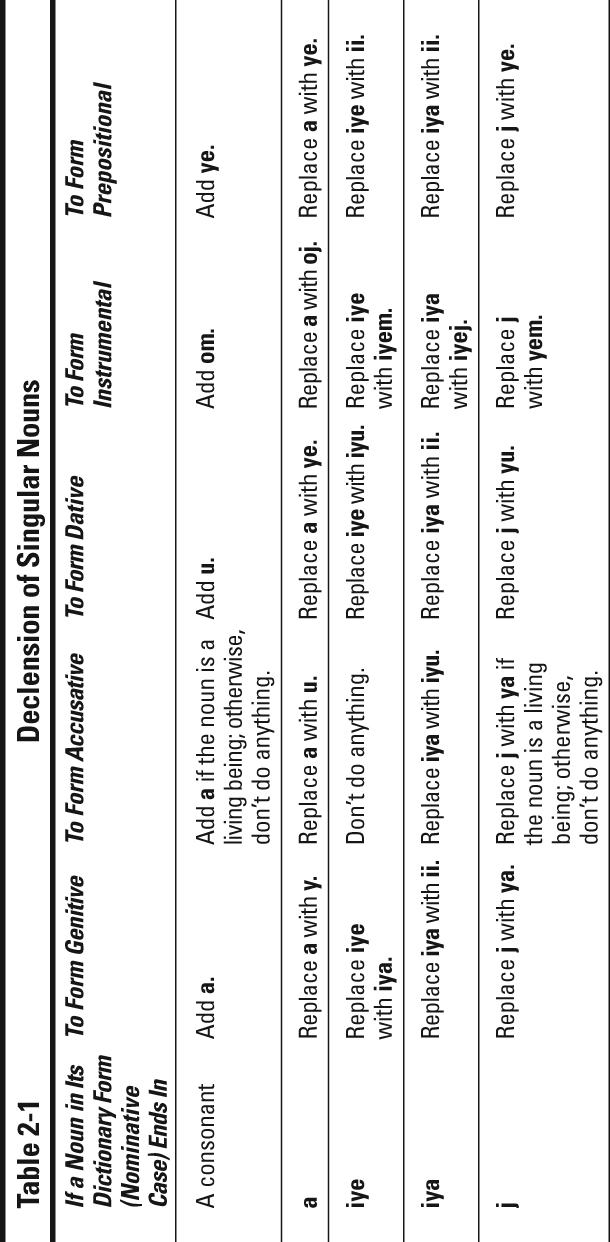

Noun declension is when you change the case endings for nouns. Table 2-1 shows you the declension for masculine, feminine, and neuter singular nouns for all the cases.

This table may look kind of scary at first, but it’s actually easy to use. Say you want to say “I bought my friend a car.” The first part of the sentence is ya kupil (ya koo-peel; I bought). But what should you do with the nouns car and friend? In this sentence, mashina (muh-shih-nuh; car) is a direct object of the action expressed by the verb kupil (koo-peel; bought). That means you have to put mashina into the accusative case.

The next step is to find the appropriate ending in Table 2-1. You find this ending in the second row, third column. The table says to replace a with u.

Now what about drug (drook; friend)? Because friend is the indirect object of the sentence (the person to whom or for whom the action of the verb is directed), it takes the dative case in Russian. Table 2-1 indicates that if a noun ends in a consonant (as does drug), you form the dative case by adding the letter u to the final consonant. The correct form for drug in this sentence is drugu (droog-oo). So here’s your complete sentence: Ya kupil drugu mashinu (yah koo-peel droog-oo muh-shih-noo; I bought my friend a car).

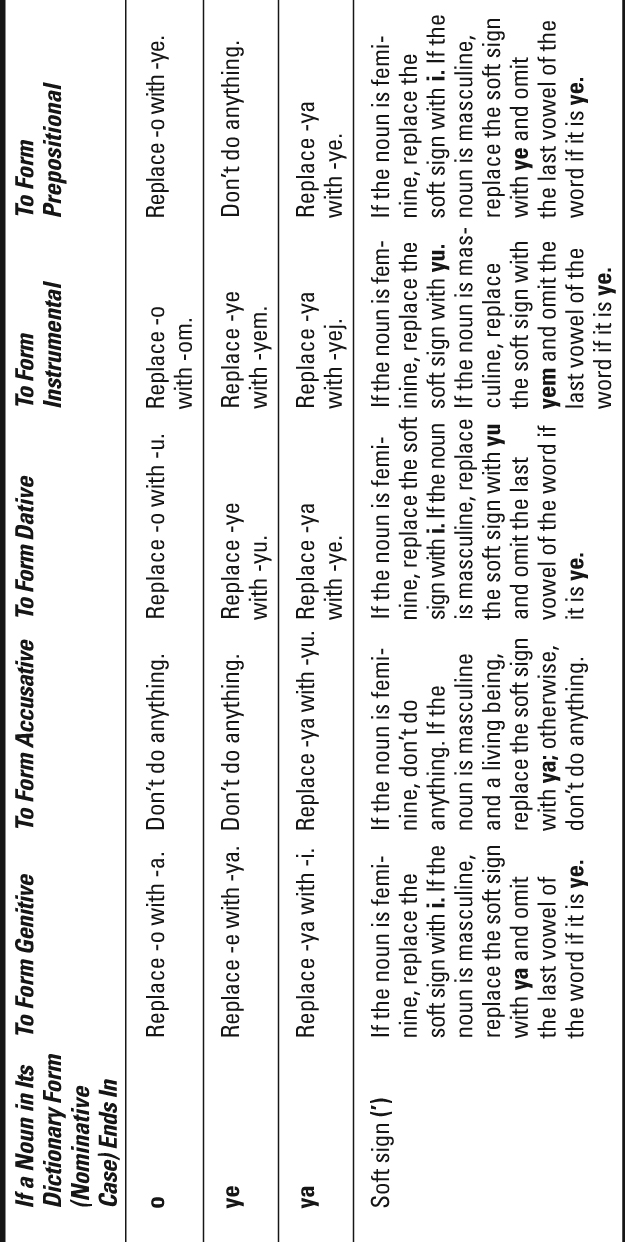

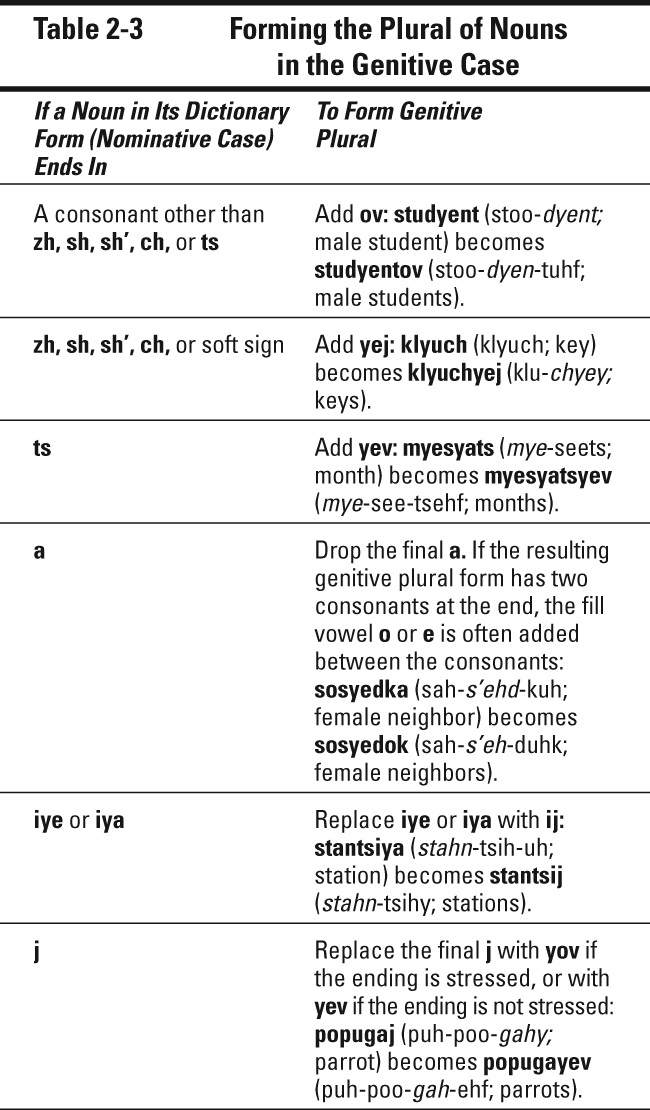

Putting plurals into their cases

As you probably guessed, Russian plural nouns take different endings depending on the case they’re in. Table 2-2 shows you the rules for plural formation in the nominative case.

.jpg)

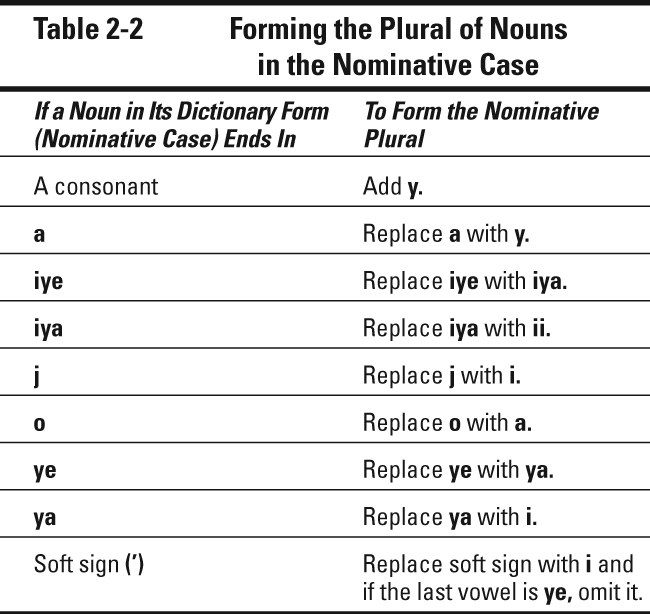

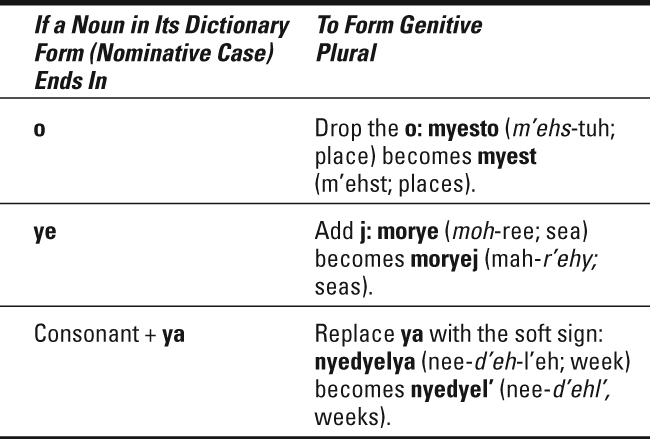

Changing plurals into the genitive case

Forming the plurals of nouns in the genitive case is a little trickier than in the other cases, so we deal with it first in Table 2-3.

Now, try to apply Table 2-3 to a real-life situation. Imagine that your friend asks you U tyebya yest’ karandash? (oo tee-b’ah yest’ kuh-ruhn-dahsh?; Do you have a pencil?). You say that you have a lot of pencils, but the word mnogo (mnoh-guh; many/a lot of) requires that the noun used with it take the genitive plural form. In your sentence, the word karandashi (kuh-ruhn-dah-shih; pencils) should take the form of genitive plural. What does Table 2-3 say about the ending sh? That’s right; you need to add the ending yej. You say U myenya mnogo karandashyej (oo mee-n’ah mnoh-guh kuh-ruhn-duh-shehy; I have many pencils).

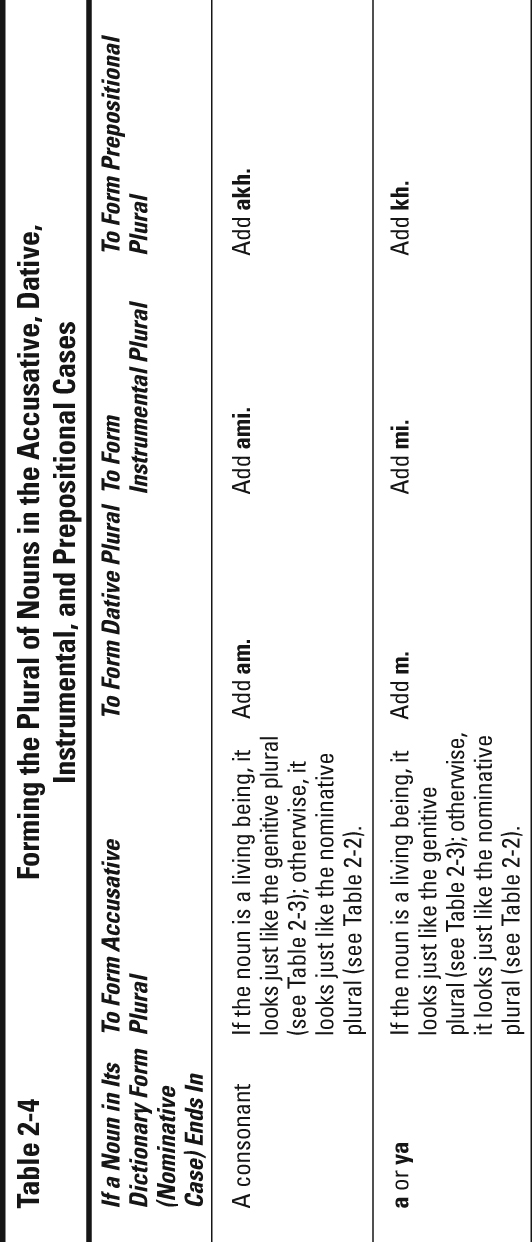

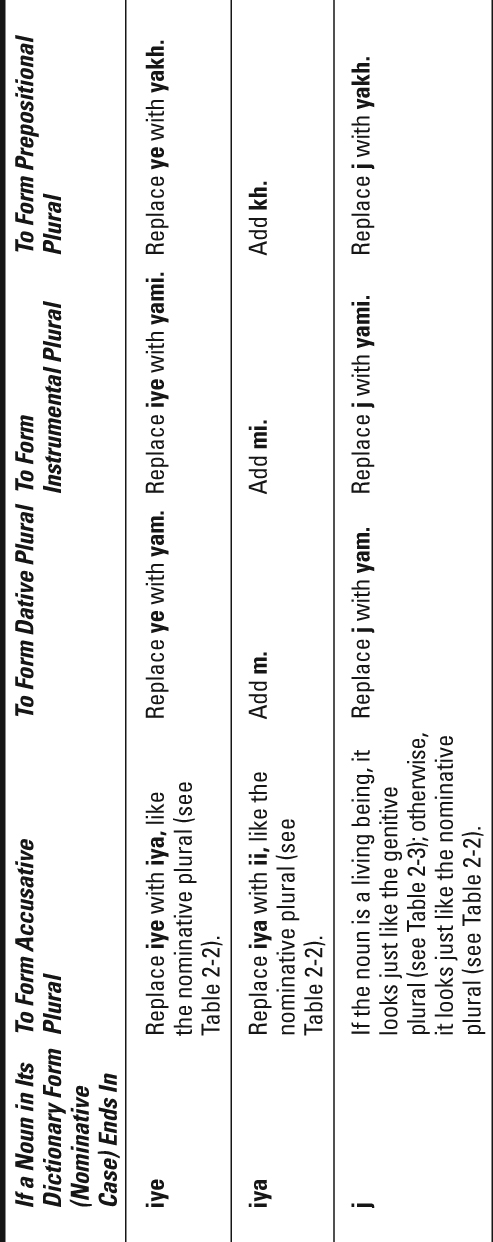

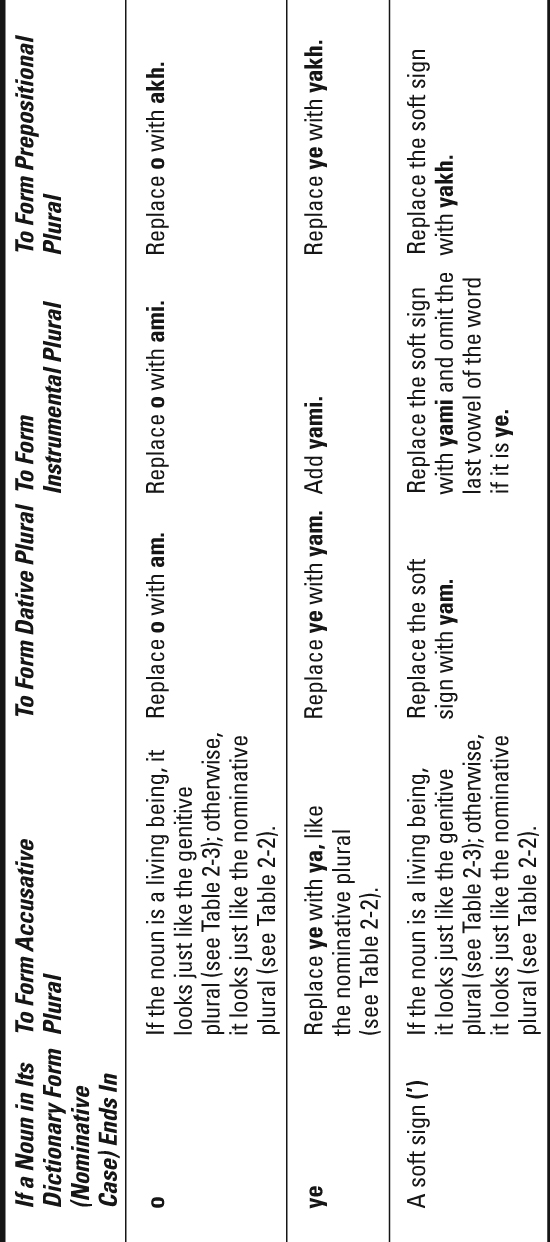

Setting plurals into other cases

Table 2-4 shows how to form the plurals of nouns for all the other cases.

Picking out pronouns

Pronouns are words like he, she, and it. They’re used in place of nouns to refer to someone or something that’s already been mentioned.

Major Russian pronouns include the following:

ya (ya; I)

ya (ya; I)

ty (tih; you [informal singular])

ty (tih; you [informal singular])

on (ohn; he)

on (ohn; he)

ona (ah-nah; she)

ona (ah-nah; she)

my (mih; we)

my (mih; we)

vy (vih; you [formal singular and plural])

vy (vih; you [formal singular and plural])

So what about it? In English, inanimate objects are usually referred to with the pronoun it, but in Russian, an inanimate object is always referred to with the pronoun corresponding to its grammatical gender. You translate the English pronoun into Russian with one of these pronouns:

on (ohn), if the noun it refers to is masculine

on (ohn), if the noun it refers to is masculine

ona (ah-nah), if the noun it refers to is feminine

ona (ah-nah), if the noun it refers to is feminine

ono (ah-noh), if the noun it refers to is neuter

ono (ah-noh), if the noun it refers to is neuter

oni (ah-nee), if the noun it refers to is plural

oni (ah-nee), if the noun it refers to is plural

For example, in the sentences Eto moya mashina. Ona staraya (eh-tuh mah-ya muh-shih-nuh ah-nah stah-ruh-yuh; That’s my car. It’s old), the pronoun it is translated as ona, because it refers to the Russian feminine noun mashina.

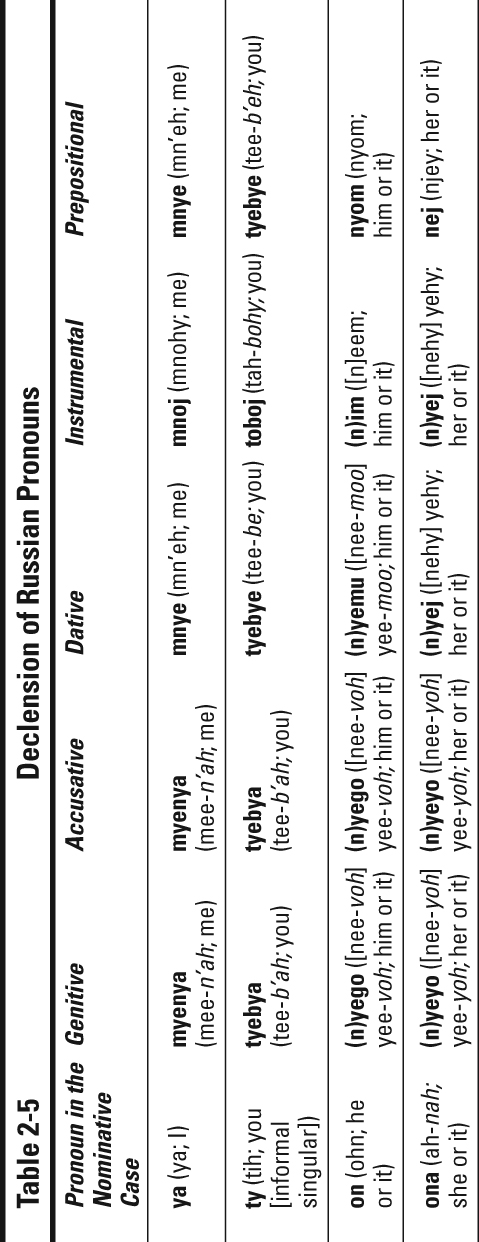

Placing basic pronouns into cases

Like nouns, Russian pronouns have different forms for all the cases. Table 2-5 shows the declension for pronouns.

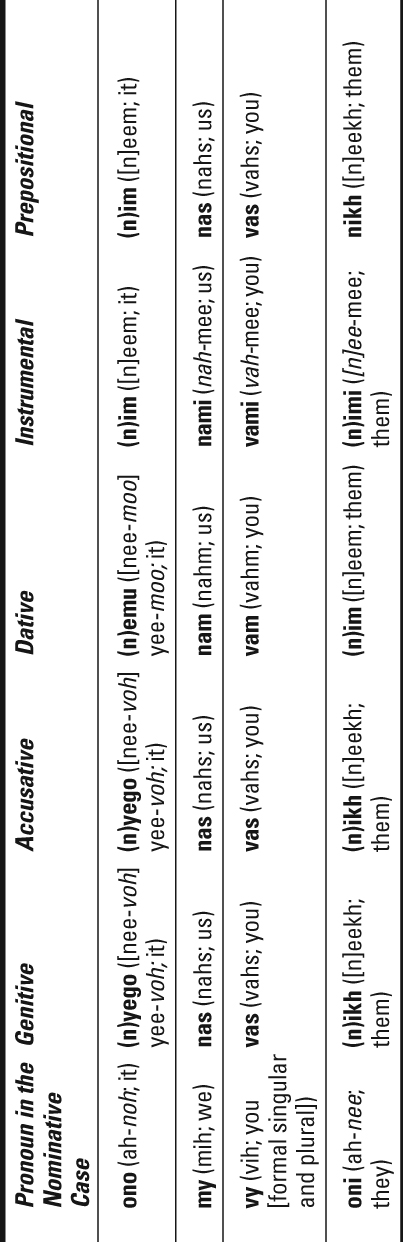

Surveying possessive pronouns

Possessive pronouns indicate ownership or possession and must always agree in number, gender, and case with the noun they’re referring to. Table 2-6 shows you how to form the possessive pronouns in the nominative case, which is by far the case you’ll use most.

Say you’re getting ready to go out on the town and you notice you lost your favorite shirt. You want to say, “Where’s my shirt?” Because rubashka (roo-bahsh-kuh; shirt) ends in a, it’s a feminine noun. Because my modifies the feminine noun rubashka, it’s written moya (mah-ya; my), according to Table 2-6. The phrase you want is Gdye moya rubashka? (gdye mah-ya roo-bahsh-kuh?; Where’s my shirt?)

Investigating interrogative pronouns

Interrogative pronouns are question words like who, whose, and which. Who in Russian is kto (ktoh), and you’re likely to hear or use this word in phrases like

Kto eto? (ktoh eh-tuh?; Who is that?)

Kto eto? (ktoh eh-tuh?; Who is that?)

Kto on? (ktoh ohn?; Who is he?)

Kto on? (ktoh ohn?; Who is he?)

Kto vy? (ktoh vih?; Who are you?)

Kto vy? (ktoh vih?; Who are you?)

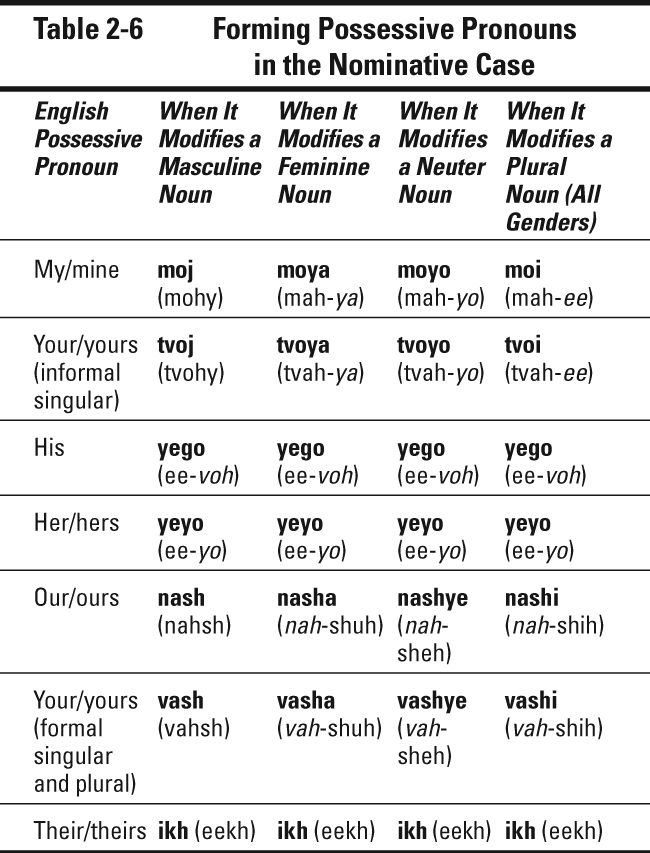

Whose in Russian is chyej (chehy), and which is kakoj (kuh-kohy). Chyej and kakoj change their endings depending on the gender, number, and case of the noun they modify. For now, you just need to know the nominative case endings in Table 2-7.

Decorating Your Speech with Adjectives

Adjectives spice up your speech. An adjective is a word that describes, or modifies, a noun or a pronoun, like good, nice, difficult, or hard.

Always consenting: Adjective-noun agreement

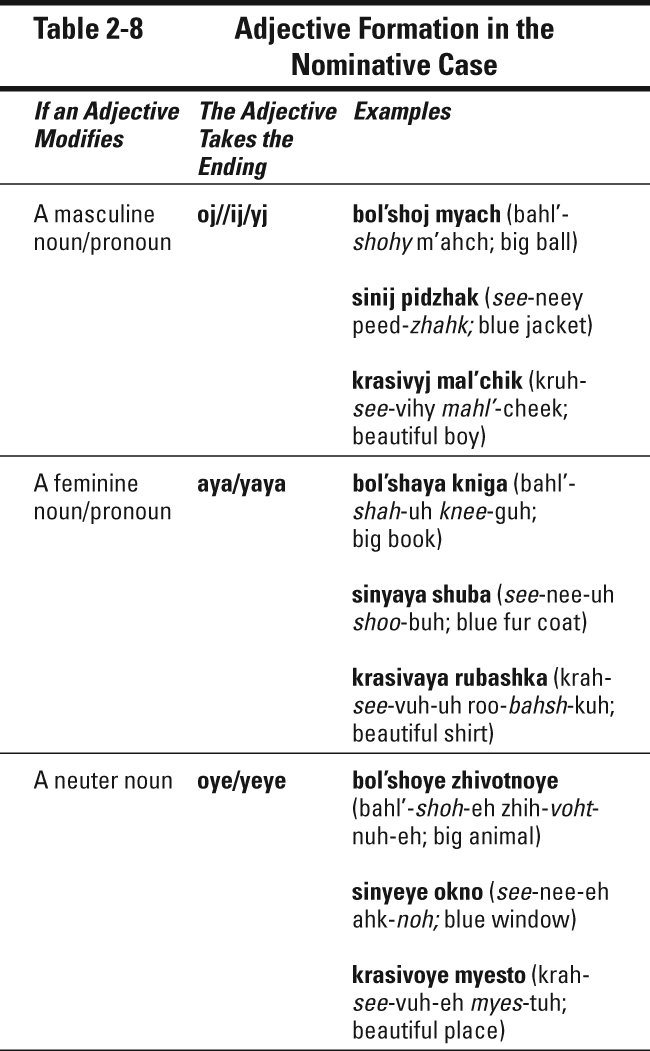

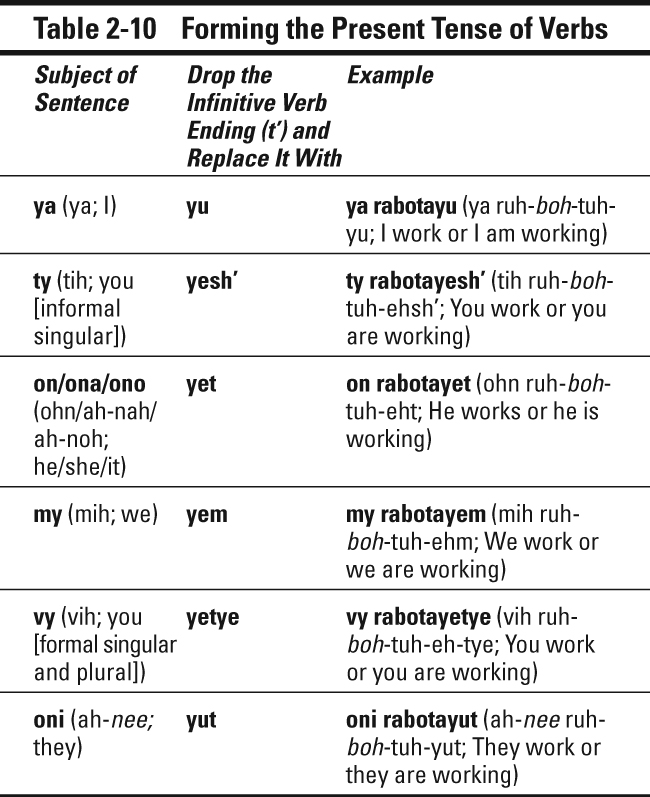

A Russian adjective always agrees with the noun or pronoun it modifies in gender, number, and case. Table 2-8 shows how to change adjective endings in the nominative case, which is the case you’re likely to see and use the most.

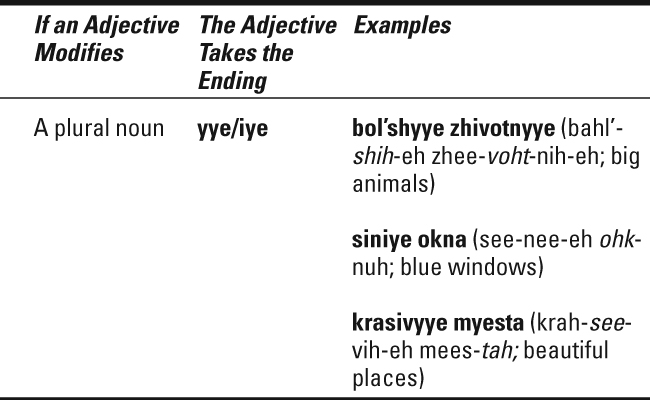

A lot in common: Putting adjectives into other cases

Table 2-9 shows how to change adjective endings for all the cases other than nominative. (Work with Table 2-8 to figure out which particular ending to use in each case.) Notice how masculine and neuter nouns take the same endings in the genitive, dative, instrumental, and prepositional cases. The feminine endings are the same for all cases except accusative. And the plural genitive and plural prepositional endings are the same.

Nowhere to be found: The lack of articles in Russian

Adding Action with Verbs

Spotting infinitives

Spotting Russian infinitives is easy, because they usually end in a t’ as in chitat’ (chee-taht’; to read), govorit’ (guh-vah-reet’; to speak), and vidyet’ (veed-yet’; to see).

Some Russian verbs (which are usually irregular) take the infinitive endings ti as in idti (ee-tee; to walk) and ch’ as in moch’ (mohch’; to be able to).

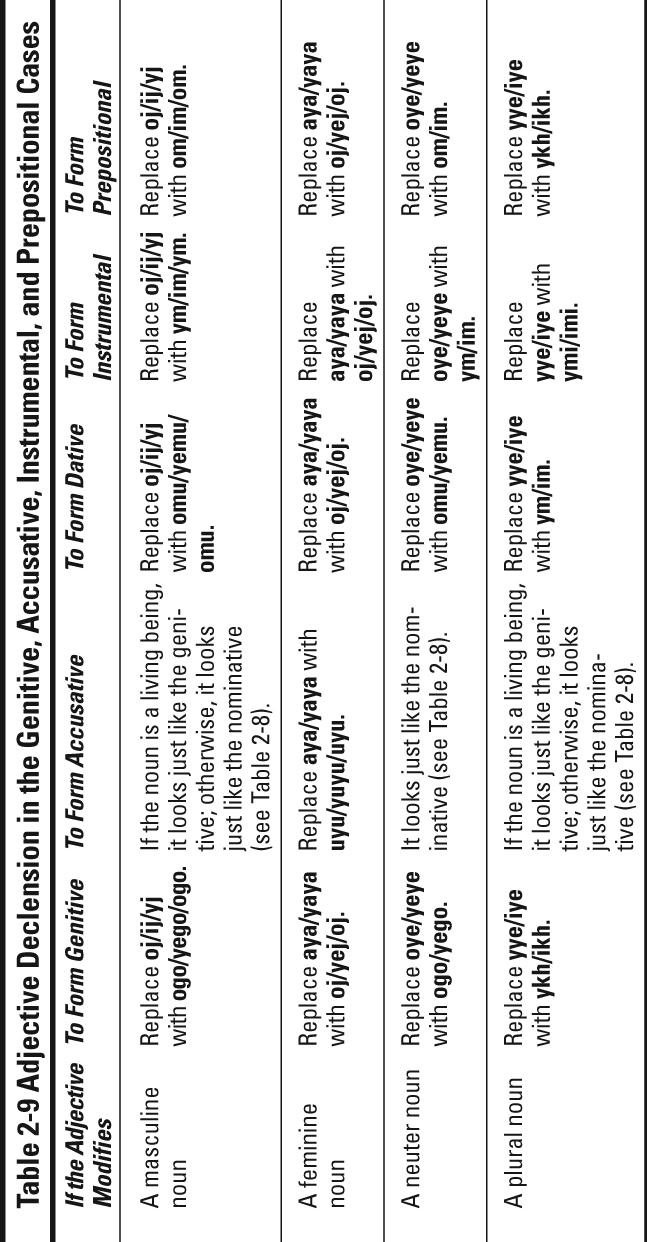

Living in the present tense

Russian verbs have only one present tense. Like English verbs, Russian verbs conjugate (change their form) so that they always agree in person and number with the subject of the sentence. To conjugate most Russian verbs in the present tense, you drop the infinitive ending t’ and replace it with one of the six endings in Table 2-10.

Keep it simple: Forming the past tense

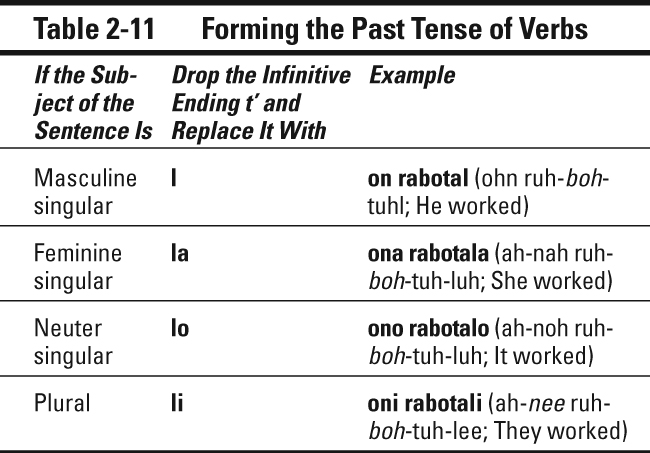

To form the past tense of a Russian verb, all you need to do is drop the infinitive ending t’ and replace it with one of four endings in Table 2-11.

Past again: Perfective or imperfective?

English expresses past events either through the past-simple tense (I ate yesterday), which simply states a fact, or the present-perfect tense (I have eaten already), which emphasizes the result of the action. Russian verbs do something similar by using what’s called verbal aspect: perfective and imperfective.

Up to this point, we’ve been withholding some very essential information from you: Every English verb is represented by two Russian verbs: its imperfective equivalent and a perfective counterpart. Usually, the imperfective is listed first, as in this example:

To read — chitat’ (chee-taht’)/prochitat’ (pruh-chee-taht’)

Chitat’ is the imperfective infinitive, and prochitat’ is the perfective infinitive. You form the perfective aspect by adding the prefix pro to the imperfective infinitive. However, sometimes the perfective aspect of a verb looks quite different from the imperfective aspect, so always check the dictionary.

If you tell someone Ya pisal ryezyumye tsyelyj dyen’ (ya pee-sahl ree-z’oo-meh tseh -lihy d’ehn’; I was writing my résumé all day), you use the past tense imperfective form of the verb pisat’, because your emphasis is on the fact of writing, not on the completion of the task. If you finished writing your résumé, you use the past tense perfective form of the verb, because your emphasis is on the completion of the action: Ya napisal ryesyumye (ya nuh-pee-sahl ree-z’oo-meh; I have written my résumé).

Planning for the future tense

To describe an action that will take place in the future, Russian uses the future tense. Although English has many different ways to talk about the future, Russian has only two: the future imperfective and the future perfective.

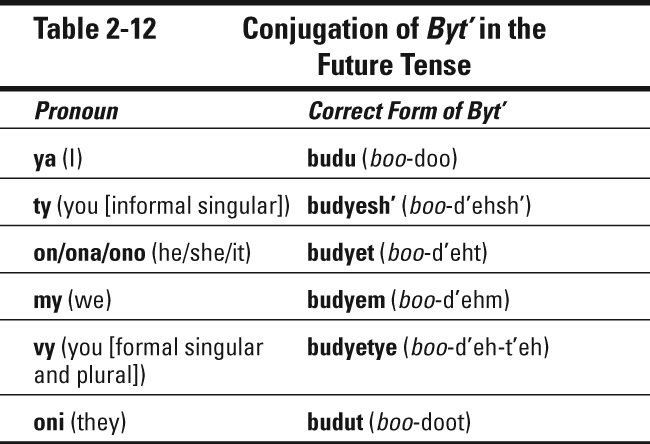

If you want to say “I will read (but not necessarily finish reading) the article,” you use the ya (I) form of the verb byt’ plus the imperfective infinitive chitat’ (chee-taht’; to read): Ya budu chitat’ stat’yu (ya boo-doo chee-taht’ staht’-yu).

Using the unusual verb byt’ (to be)

To express the verb to be in the past tense, you need to use the proper past-tense form of the verb byt’:

byl (bihl; was), if the subject is a masculine singular noun

byl (bihl; was), if the subject is a masculine singular noun

byla (bih-lah; was), if the subject is a feminine singular noun

byla (bih-lah; was), if the subject is a feminine singular noun

bylo (bih-luh; was), if the subject is a neuter singular noun

bylo (bih-luh; was), if the subject is a neuter singular noun

byli (bih-lee; was), if the subject is a plural noun or if the subject is vy (vih; you [formal singular])

byli (bih-lee; was), if the subject is a plural noun or if the subject is vy (vih; you [formal singular])

To express the verb to be in the future tense, you have to use the correct form of the verb byt’ in the future tense. (For conjugation, refer to Table 2-12.) To say “I will be happy,” you say Ya budu schastliv (ya boo-doo sh’ahs-leef), and for “I will be there,” you say Ya budu tam (ya boo-doo tahm).