My parents were remarkable, in their very different ways. What they did have in common was their energy. The First World War did them both in. Shrapnel shattered my father’s leg, and thereafter he had to wear a wooden one. He never recovered from the trenches. He died at sixty-two, an old man. On the death certificate should have been written, as cause of death, the Great War. My mother’s great love, a doctor, drowned in the Channel. She did not recover from that loss. I have tried to give them lives as might have been if there had been no World War One.

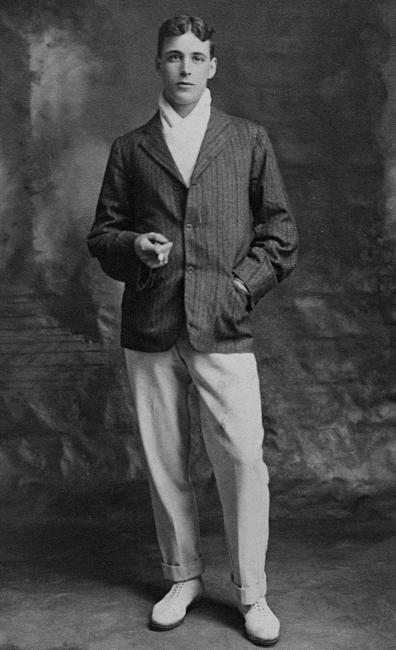

Easy for my father. He grew up playing with the farmers’ boys in the fields around Colchester. He had wanted to be a farmer, all his life, in Essex or in Norfolk. He did not have the money to buy a farm, so I have given him his heart’s desire, which was to be an English farmer. He excelled in sports, particularly cricket.

My mother nursed the wounded for the four years of the war, in the old Royal Free Hospital, which was then in London’s East End. When she was thirty-two, she was offered the job of matron at St George’s Hospital, then one of the greatest hospitals anywhere. It is now a hotel. Usually women had to be in their forties to be offered matronhood. She was formidably efficient. I used to joke, as a girl, that if she were in England she would be running the Women’s Institute or, like Florence Nightingale, be an inspiration for the reorganization of hospitals. She was also musically talented.

That war, the Great War, the war that would end all war, squatted over my childhood. The trenches were as present to me as anything I actually saw around me. And here I still am, trying to get out from under that monstrous legacy, trying to get free.

If I could meet Alfred Tayler and Emily McVeagh now, as I have written them, as they might have been had the Great War not happened, I hope they would approve the lives I have given them.