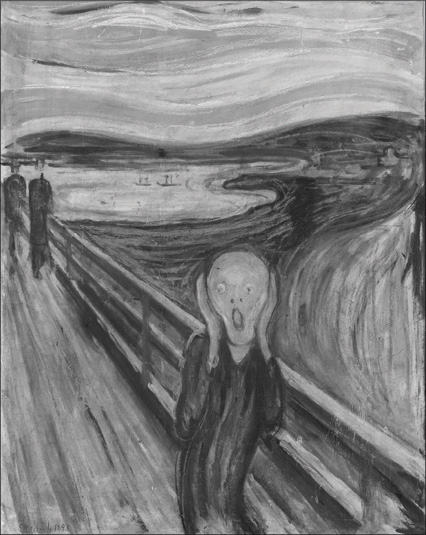

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893, oil, tempera, and pastel on cardboard, 91 x 73 cm, National Gallery of Norway. Wikimedia Commons

History Is Not One Damn Thing after Another

SUMMARY

A first step in finding a politic which is “neither right nor left nor religious” is construing history correctly. For some, “history is just one damn thing after another.” This famed phrase well depicts those who believe history has no meaning, no direction or goal, no ultimate purpose.

Many Christians also think this: “It’s all going to burn, and none of this matters.” What matters, they say, is the human soul “going to heaven when we die.” No need to concern ourselves with troubling social or political matters because “God’s got this.” Politics and social affairs are of no concern to the faithful.

Many Jews, Muslims, and Christians know better. Some prominent early Christians, in fact, believed such spiritualizing to be a grave heresy that would destroy the Christian faith. They saw human history as the stage for the unfolding of the drama of God’s work. In this drama God was assured to be the victor, even if God’s ways are often inscrutable, even exasperating to those who love God. This God who had created a good creation would restore it, redeem it, save it. This God would set right the injustice and violence, remove the arrogant mighty ones from their throne rooms and White Houses, fill up the hungry, and bind up the oppressed.

In this drama some humans, feeble and petty as they may be, ally themselves for the work of God. Meanwhile, many of the preening, arrogant powers array themselves against both God and humankind. Those arrogant powers often serve as the handmaidens of death, while the God of life keeps intruding, or so it appears to the powers, bringing light into the darkness.

But human history is not one damn meaningless thing after another, even if the horror of the mundane evil propagated by the powers tempts us to despair. History has a goal, a direction toward a climax: the author of life shall write a tale, has written a tale, in which all lies and greed and ugliness and war; prisons and lusts, oppression and hate; hostility, disease, contempt, and envy; all shall be undone and set right, and there shall come a triumph of truth and goodness and beauty, which no ear has yet heard, and no eye has yet seen.

EXPOSITION

The Scream has been called the Mona Lisa of the twentieth century. Edvard Munch’s iconic painting arose from a dreadful vision he had one day at sunset. Walking along a fjord in his native Norway, he said he “sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.” That scream captures the modern sense of despair, in which no hope remains, only anxiety, loneliness, and despondency.

Munch’s artistic angst illustrates well some common philosophical convictions about history: that history has no direction or is merely an endless cycle of repetition or is but one damn meaningless thing after another. There are also religions, supposedly Christian versions of such, that think that human history is ultimately unimportant. These alleged Christian versions postulate some hope, some purpose, but it is a purpose beyond history, outside of history. It is a reward “up there,” souls floating off to heaven. “Our true home,” they say, “is in heaven. We need not concern ourselves with social or political or historical matters.” One therapeutic solution to Munch’s Scream is simply not to look too closely at history, not get ourselves involved in matters that don’t concern us in our spiritual contentment. If you don’t pay attention to the death camps or the brokenness of the cities or the systemic greed undergirding our economies, then you need not feel the despair. You simply ignore it, look beyond, to the sweet by-and-by.

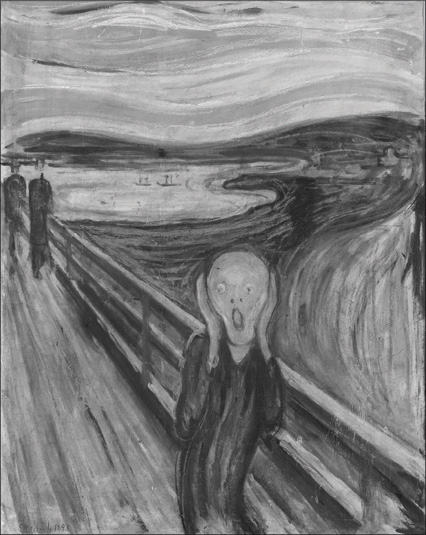

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893, oil, tempera, and pastel on cardboard, 91 x 73 cm, National Gallery of Norway. Wikimedia Commons

This is Marx’s classical critique: religion as the opiate of the masses.

But as much biblical scholarship has been contending of late, “going to heaven” is not the point of the New Testament, nor did early Christians believe it so.

Along with recent biblical scholarship, the poets and prophets and song-singers have always known better. The Hebrew prophets envisioned a day in which “the lamb shall lie down with the lion,” “the nations shall learn war no more,” and “swords shall be beaten into plowshares.” The poets and lyricists of our own day insist that “a change is gonna come” and that we “still haven’t found what [we’re] looking for.” And Martin Luther King Jr. proclaimed that he had a dream and that “the arc of history is long, but it bends toward justice.”

All these poetic utterances point us toward hopefulness. Each assumes that history is not, in the final analysis, a meaningless morass of vanity. Instead, history has a direction: injustice undone, brokenness bound up, captivity taken captive. This is the goal of history, the end of history. We need not confuse “end of history” with the termination of time; it is, rather, best considered as the final goal toward which all things are moving.1

Historic Christianity insists precisely this: that history is headed toward a glorious re-creation the likes of which only poets can begin to voice.

This conviction is a most significant starting point for considering a sociopolitical vision for Christian practice.

Hope as an Interpretation of History

This idea—a goal of history—entails the notion of hope.

This is where the American myth and Christian teaching have a high degree of overlap: both assert the notion of a direction to history and thus the practical importance of hope. There is similar overlap with the secularist who speaks of progress, assuming some direction in human history.2 As the philosopher John Gray describes John Stuart Mill, one of the preeminent philosophers of the liberal tradition in the West: “he founded an orthodoxy—the belief in improvement that is the unthinking faith of people who think they have no religion.”3

If it is true that Christianity does proclaim that history matters and is going somewhere, then it turns out that many American and secularist forms of hope are more Christian than the otherworldly dreams of some Christians. Or, at a minimum, we can say that such Americans and secularists are more Christian in their conviction regarding the immeasurable worth of the whole of human history.

When Americans and secularists insist that history matters—that social policy and scientific concern for the earth matter, that economic policy and staggering disparities in wealth matter, that the industrialization of war and imprisonment for profit matter—they show themselves, in this regard, more Christian than many Christians.

The hope of heaven, in other words, too easily becomes an ahistorical hope, a hope that cares nothing for the unfolding of the human drama, except perhaps to hope that sufficient religious or moral choices are rightly made so that the soul can sweep through the Pearly Gates.

In this way, some American revivalists may have done more to undermine Christianity in America than the secularists by making the locus of Christianity the individual’s judgment before the throne of God, a religion that has little to say to the teeming and throbbing pain of human history and instead calls us to cast our vision to an afterlife removed from care for human history or for God’s good creation. Such a tendency contributed to Malcolm X renouncing Christianity and embracing Islam. “The white man has taught us to shout and sing and pray until we die, to wait until death, for some dreamy heaven-in-the-hereafter, when we’re dead, while this white man has milk and honey in the streets paved with golden dollars right here on this earth!”4

One of the failings of the secularist notion of progress is its vague lack of content: What does progress entail? What does it look like? What is its content?

Similarly, the Christian notion of hope must attend to these same questions. The biblical creation account, in which Jews and Christians maintain that the creation itself is good, is indispensable in beginning to answer such questions. The Genesis account about creation is not a sort of crypto-scientific description best read as a literal account of the unfolding of the cosmos. Instead, the Genesis account insists on the moral and aesthetic goodness of the creation grounded and rooted in the abundant generosity of God. It presumes a community inherent in the very nature of God and that this self-giving God invited all creation, and humankind in a special way, to participate in the joyous work of tilling and cultivating in the unfolding story of the garden of God.

And yet death and death’s handmaidens duped the humans, vandalizing the abode of God and humankind. And yet more, this God who is good and patient and long-suffering did not leave humankind to its own devices but would act in love and power and justice to set things right—while still honoring humankind’s radical freedom to reject the good ways of God—to free humankind from the bondage in which it found itself.

“New heavens and new earth”—that’s what one of the prophets called the greatly anticipated redemption of God. Christianity was not concerned first and foremost with some realm of disembodied spirits beyond the pale of human history.

Consider the stunning objection of one of the early church martyrs, Justin. He was arrested and beheaded for his faith. His commentary is striking. There are some “who are called Christians,” he said rather derisively, who insisted that “their souls, when they die, are taken to heaven.” He classified such people among “godless, impious heretics.”5

This is an ironic, odd reality: that an early defender of Christianity who refused to submit to the demands of the Roman Empire, who insisted that Jesus was Lord, and who was executed for his stance, would say that our American Joe Christian is not in fact a Christian but a heretic. Justin was not executed because he was religious. He was executed because he held to a competing interpretation of human history. Justin held to an alternative politic that entailed that the Word of God revealed in this Jesus of Nazareth was the only rational explanation that made sense of our lives and was the only rational ground for hope. The resurrecting power of God which had raised this Jesus from the dead would not only raise all of us but also make new the heavens and the earth and set all things right.

Jesus and other early Christians were not executed because they were spiritual. They were executed because their politic was a threat to the powers that be.

The Content of the Hope

It is not the afterlife for which the prophet longs but the setting right of this life: the pain of lost loves and the death of infants, of old griefs and deep regret, of the weeping of mothers or the cries of war. All shall be wrought up into the work of this God who shall wipe away every tear from every eye and make all things right.

Hear, for example, the Hebrew prophet Isaiah:

For I am about to create new heavens

and a new earth;

the former things shall not be remembered

or come to mind.

But be glad and rejoice forever

in what I am creating;

for I am about to create Jerusalem as a joy,

and its people as a delight.

I will rejoice in Jerusalem,

and delight in my people;

no more shall the sound of weeping be heard in it,

or the cry of distress.

No more shall there be in it

an infant that lives but a few days,

or an old person who does not live out a lifetime;

for one who dies at a hundred years will be considered a youth,

and one who falls short of a hundred will be considered accursed.

They shall build houses and inhabit them;

they shall plant vineyards and eat their fruit.

They shall not build and another inhabit;

they shall not plant and another eat;

for like the days of a tree shall the days of my people be,

and my chosen shall long enjoy the work of their hands.

They shall not labor in vain,

or bear children for calamity;

for they shall be offspring blessed by the LORD—

and their descendants as well.

Before they call I will answer,

while they are yet speaking I will hear.

The wolf and the lamb shall feed together,

the lion shall eat straw like the ox;

but the serpent—its food shall be dust!

They shall not hurt or destroy

on all my holy mountain,

says the LORD. (Isa. 65:17–25)

A great abundance of many of the finest lines of poetry inscribed in human history is grasping after, longing after, painting a glimpse of this coming hope. The street of gold, God wiping every tear from every eye, the great river that flows from the throne of God lined on both banks with the very tree of life—all these poetic images of the triumph of God—are not depicted in heaven in the biblical text. Instead, Revelation 21–22 depict such glory occurring here, even here in the midst of human history, even here in the midst of us. Oppression shall be undone, infidelity cast out, captivity itself taken captive, not in the sweet by-and-by but in the climax of the story of God in our midst.

The biblical vision, then, will countenance no supposed withdrawal from politics. The prophets will hear none of this religious pretending that history does not matter, all in the name of a pietistic assertion that “God’s got this.” The biblical texts refuse to minimize the importance of social and historical developments, will not look the other way as the scoundrels of death vandalize and terrorize, will not let us look away from the bitter cries of mothers, the lonely privation of old men, the needless deaths of children.

No! “Captivity has been taken captive.” “Let my people go!” “Let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.” “Do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with God!”

The great paradigmatic moment of political encounter in the founding narrative of the Christians comes with the gospel: “Change, and believe in the good news of the reign of God.” This new political movement of God would entail specific practices unlike those of the nations, unlike those of the powers whom we have falsely assumed have the monopoly on political power. This new political movement would offer the world something at which kings and rulers would shake their heads: love of enemies, practices of reconciliation, sharing of wealth, honoring of marriage, renunciation of our varied practices of greed and lust, and an embrace of all the practices of life and mercy and kindness.

Or thus said Jesus.

In all these and many compelling ways besides, the Scriptures call us to face the pain and brokenness of human history.

And we are called to have the courage to play our part: to be brave as the soldier, committed as the activist, devoted as the evangelical, sedulous as the journalist—speaking to, acting for, sowing the seeds of the world that is on its way, knowing that it requires great labor, perseverance, and a willingness to suffer, and promises, too, on the journey, of deep joy and gladness, friends and fellow pilgrims, called as we are to be bearers of the end of history. We shall refuse to vindicate Marx by refusing to let our faith be an opiate of the masses; we shall face the pain and oppression squarely and proclaim the good news that the hope of all humankind, evoked in and out of our tears and cries and confusion and anger, has come, shall come. And we shall dare to live by it.

So: No, history is not one damn meaningless thing after another. Moses, the prophets, and Jesus, each in their own way, insisted that history has a goal, a direction, an intrinsic and inescapable importance in the purposes of the Creator of all things good. And woe be unto those who stand in the way of this great God’s unfolding of this narrative, which will not be stopped until all that is beautiful and good and true is made manifest in our midst.

1. A great deal of work is currently being done in the West on how to make sense of the Christian doctrine of original sin given the now-pervasive acceptance of the theory of evolution and the rise of the human species by means of natural selection. Much of this work appears fruitful. It is not as clear to me that similar work is being done with regard to Christian eschatological teaching, given new insights in cosmology and theories of relativity and the like, but this seems needful as well.

2. In his typical provocative and insightful fashion, Andrew Sullivan notes that we all have a “religion” these days, even the atheists, in some attenuated fashion, and he explicitly draws the parallel between Christian faith and the secularist progress myth: “Seduced by scientism, distracted by materialism, insulated, like no humans before us, from the vicissitudes of sickness and the ubiquity of early death, the post-Christian West believes instead in something we have called progress—a gradual ascent of mankind toward reason, peace, and prosperity—as a substitute in many ways for our previous monotheism. We have constructed a capitalist system that turns individual selfishness into a collective asset and showers us with earthly goods; we have leveraged science for our own health and comfort. Our ability to extend this material bonanza to more and more people is how we define progress; and progress is what we call meaning.” Andrew Sullivan, “America’s New Religions,” Intelligencer, December 7, 2018, http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2018/12/andrew-sullivan-americas-new-religions.html.

3. John Gray, Seven Types of Atheism (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2018), 36

4. Malcolm X and Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1964; repr., New York: Ballantine Books, 2015), 224.

5. Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, 80, Ante-Nicene Fathers, ed. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson (1885; repr., Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1996).