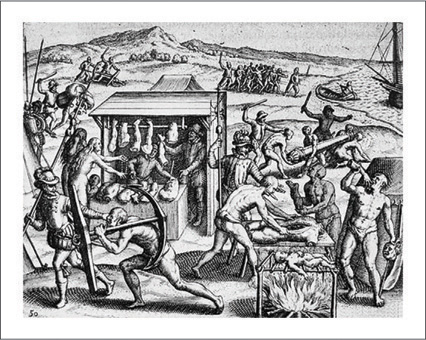

Theodore de Bry, depiction of Spanish atrocities in the New World, 16th century. Wikimedia Commons

Liberal Political Puissance Is Not the Goal

SUMMARY

The primary task of Christian community is not to dominate the political communities that do not accept basic Christian claims. Our task is not to dominate the debates between liberal liberals and the conservative liberals, to forcibly bring to bear some redacted form of Christian values on a system that knows not Christ. To pursue such dominance would, in fact, be a rejection of basic Christian faith and practice. We live in an out-of-control fashion precisely because we serve a Messiah who had no messianic complex but who first and foremost obeyed the will of God, even if it meant losing, even if it meant getting himself killed.

EXPOSITION

The primary task of the community of Christians is not to run the unbelieving world, is not to dominate the political communities that do not accept basic Christian claims. Two reasons for this are straightforward and will provide the outline of this chapter. First, ultimate and radical liberty provides the ground of Christianity. Second, ultimate and radical liberty must also characterize any and all means of the spread of Christianity.

These claims are of great importance. They allow us clearly to see that many of the arguments about Christian values turn out to be a bastardized form of Christianity precisely because of the use of and reliance on coercive power. But any morality, practice, or conviction imposed through violence cannot be, by definition, a Christian morality, practice, or conviction. Christianity is a call to divest itself of such forms of power.

An Ultimate and Radical Liberty Provides the Ground of Christian Faith and Practice

Even prior to the coming of the Christ, Israel knew that our God is a God of steadfast love whose love endures forever. The covenant relationship with Israel was grounded in a love that allowed Israel to “go whoring after other lovers.” Beyond Israel, all peoples have been given the liberty to reject the call of God. All people have been given the liberty to reject all that is right and good and beautiful.

This is not to say—and this is a terribly important caveat—that there are no consequences for such rejection. One may ignore, say, the nature of social relations or the tendencies of particular political commitments or the field of gravity. But in each of these cases there are consequences for one’s ignorant choices.

But the nature of God’s covenant relationship with Israel—in spite of the radical liberty granted Israel to reject the steadfast love of God—nonetheless entailed a place of deep coercion. Israel participated in, and the God of Israel participated in, practices of violence and coercion. This appears to be true, at a minimum, because Israel was founded as a geographically bounded nation. Given that Israel’s God was committed to Israel’s flourishing in the world as a light to the nations, and given that human history was bloody and violent, and given that survival as a geographically bounded nation entailed practices of war, this God of Israel got his hands dirty, we might say. Precisely because this God was not unconcerned with the injustices of the mighty and the violence of the wicked, this God refused to allow the wicked and the unjust to overthrow God’s people. Thus, the geographically bounded Israel coincided with the legitimation of, even call to, war.1

But even within this qualified acceptance of war, the prophets depicted a coming day of a new peaceableness in which swords would be beaten into plowshares and swords into pruning hooks and the nations would learn war no more.

Thus, with the coming of Messiah a new model of kingship was chosen. Not one in which history no longer mattered in favor of some spiritual kingship. This Messiah was a new David, a true king, indeed even King of kings. He compared to emperors, who called themselves sons of the gods, for he was heralded the Son of God. And yet, as the prophet foretold, kings “shut their mouths” because of him. He came among us as one who does not break a bruised reed or extinguish a barely flickering wick. He does not bear the rod of iron of the kings of old but suffers the blows that were all ours to bear. The distinctive of his alternative kingship is not that it is spiritual—many of the kings and presidents and prime ministers have their own spirituality, after all. Instead, his alternative kingship is located precisely in the manner of his bearing of authority: the gentiles, he said, lord authority. But among you, it shall not be so. You shall be servants of all, not lords of all.

This Jesus was not crucified because he was spiritual. He was crucified because he incarnated a new way of being king and a new way of being human, a new way that terrifies even the most spiritual of kings and presidents and prime ministers to this day.

In addition to this new model of kingship, this new people would not be geographically bounded. This people is drawn from every tribe, every land, every nation. This is one of the great political facts of Christianity often overlooked and often ignored with regard to the rush to war. For when one nation makes war against another, it is often, very often, Christians in one nation killing Christians in another.

This great political fact is ignored in other aspects, say in our walls and boundary building. Given that we live “between the times,” it may be legitimate for a nation-state to have a protected border, even though any and all borders clearly stand in opposition to the end of history. And given that we Christians are the people who bear witness, in our common life together, to the end of history, we Christians cannot first and foremost be concerned with a border but must be more concerned with our neighbor on either side of that border, must be more concerned with our brother and sister with whom we share baptism on either side of that border. Walls and borders and national self-interest must always be granted only provisional, contingent importance, and not an ultimate one.

One important objection: Jesus and the early church told tales of coming judgment. And these depictions of judgment are inherently violent. Are such visions not coercive, at least psychologically? Might one even say that the pictures of coming destruction are religiously abusive?

Perhaps. It may be, as some scholars have claimed, that some of the writers of Scripture failed, themselves, to sufficiently comprehend the radical nature of the revelation of God in Christ and continued to employ old apocalyptic visions of punishment that stand at odds with the newness revealed in Christ.

While this is an objection worthy of note, another significant possibility runs in a different direction. To posit the theological construct of judgment is to say something we know to be true, that there are consequences for our injustice, our violence, our greed. On the one hand these consequences may be what we might call natural. The horrors that come upon us may be the natural outgrowth of our own rebellion and failings and self-centered and systemically propagated longings after wealth and power and pleasure.

The liberal liberal hankering after a sexuality with no boundaries or a conservative liberal hankering after a market with no boundaries both show themselves as naive as the little boy who insists gravity does not pertain to him. His insistence may be altogether sincere as he jumps from his tree house with the conviction that he may fly by flapping his arms. But there will be consequences, and wishful thinking cannot will them away.

This is one crucial way to configure the necessity of judgment.

On the other hand, to uphold the theological importance of judgment may be a fulfillment of the human longing that the Creator of all things would in fact judge. Only the naive or philosophically adolescent desires no judgment. Once we have seen or suffered or witnessed oppression, we most undoubtedly want judgment. This longing for judgment need not be a rapacious longing for vengeance or retaliation. But it is surely deep within us to long that the Creator of all things would definitively pronounce, would establish with all authority and finality,

Joy, not bitterness.

Love, not hostility.

Life, not death.

This, not that.

Some sort of depiction of judgment as this must arise out of the claim of a crucified and resurrected Lord.

While it should be clear already, it may be helpful to note again that this call to nonviolence is most certainly not a call to passivity or codependence or any form of cowardly shrinking away from injustice or oppression. We are not called to let others run over us, and we must not equate “turning the other cheek” with any such passivity. Jesus enkindled within his followers a fertile imagination to look for a third way between violence and passivity, between retaliation and running away.

An Ultimate and Radical Liberty Must Also Characterize Any and All Means of the Spread of Christianity

An apple tree does not yield lemons, and one gets to an oak only by the acorn. In the same way, the fruit of authentic Christianity comes only by means of the divestment of coercion and violence.

The name commonly given to the temptation to impose Christianity on the world is Constantinianism. Constantine was the Roman emperor who made Christianity a legal religion, banning persecution of Christians. (This latter fact is, of course, something to celebrate.) But Constantine’s nominal acceptance of Christianity (he appears to have remained a rather cold-blooded emperor who finally accepted baptism on his deathbed) meant first that the means of empire began to be commingled with the church.

By the end of the fourth century, Christianity was made, under Emperor Theodosius, the only legal religion in the empire. This entailed a radical social change. Within one century Christianity went from being officially persecuted under Emperors Decius and Diocletian at the end of the third century to being the only legal religion, and one thus could be persecuted for practicing some other religion, by the end of the fourth century. Moreover, up until the end of the third century, all extant writings from the church fathers exhibit the consistent and unanimous rejection of Christians killing in warfare, but by a century later one had to be a baptized Christian in order to be a member of the Roman military. By the time of Christmas Day 800 CE, with the coronation of Charlemagne came the outrageous employment of imperial violence in service to baptism. You can either be baptized, said Charlemagne, or we will kill you.

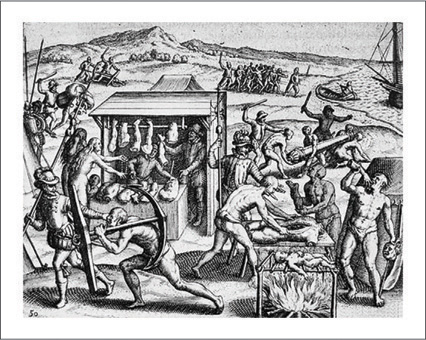

Of course, this sort of bastardized form of medieval European Christianity would exhibit its own particular horrors when it would come to the Americas. Bartolomé de las Casas, a Dominican priest who witnessed firsthand some of the work of the conquistadors, concedes it is not possible sufficiently to describe the atrocities, so great was the terror. He documented how the Spanish conquistadors would tear babies from their mothers’ breasts and smash their brains on the rocks. When those sixteenth-century Christians arrived in the Americas, they also brought with them their dogs, unleashed to hunt the indigenous as if they were wild pigs. They would cast women and children into pits full of stakes, impaled until the pit was full. They would gather together hundreds of natives and then systematically massacre them, sparing none, and meanwhile tie up the leading citizens, dangling them from gibbets, their feet just above the ground, and roast them alive. They set up butcher shops, hacking up the men and women, selling their parts for food for dogs.

The conquests entailed cultural domination as well. The Requerimiento aptly symbolizes such cultural violence. Arriving to conquer some new people, the conquistadors would read aloud the Requerimiento. The proclamation would be read in Spanish (which, obviously, the indigenous population did not understand) and required them to accept the rule of Spanish Christian kings, because the pope had, after all, granted such dominion and sovereignty to the Spanish monarchy. They could accept such terms, so the proclamation announced, or face war, slavery, or death. Furthermore, they would insist that any deaths that followed were the fault of the natives for not accepting Spanish Christian rule.

Meanwhile, back in the great halls of academia in Europe, the churchmen were debating whether the natives were in fact people, were in fact human, or not.2

It is too simple and too naive to say, Oh, we know better than those medieval barbarians; we have separation of church and state. The matter is more subtle and dangerous than that for the Christian. The issue is not simply whether to post the Ten Commandments in the Supreme Court House of Alabama or to enforce a policy of school prayer or some such explicit so-called religious practice or totem. It is the Constantinian logic that is of greater danger: if our goal is legitimate, then state-sanctioned coercive violence is a legitimate means toward that end. It is often the secularists who find great allies among the Constantinians on this score. Democracy and capitalism must prevail; thus by hook or by crook we shall prevail, and we will not go down without a fight to coercively enforce our will upon the world: whether tromping from sea to shining sea based on some delusion of Manifest Destiny; whether by subversion of the legitimately elected president of Chile, leading to the ruthless Pinochet dictatorship; whether by propagation of the promise of a world conflagration if we are threatened with the very weapons that we alone have employed, as in the rise of the US policy of MAD—“mutually assured destruction” by means of nuclear weapons; or whether by a state of perpetual war, as that in which we now find ourselves, our drones as fiery manifestation from the sky of judge, jury, and executioner.

Theodore de Bry, depiction of Spanish atrocities in the New World, 16th century. Wikimedia Commons

The issue is whether we Christians explicitly set aside the teachings of Jesus in order to effect some desirable social end; whether we will take seriously as a sociopolitical stance Jesus’s insistence that it is the gentiles who lord authority over others, but that it is not to be so among us; or Jesus’s teaching that we should love our enemies, pray for those who abuse us, and forgive seventy times seven; or Jesus’s proclamation that the kingdom of heaven comes by mercy and peacemaking and truth telling and a willingness to suffer in the pursuit of the new order of God in the world.

Our prophetic voice must be raised in protest against those who carry the name of Christ yet ignore the way of Christ.

Even more, our kerygmatic voice of proclaiming, winsomely, the constructive alternative of the gospel must be raised in the public square. For

Your responsibility is a “to—”:

you can never save yourself by a “not to.”3

And so it is not sufficient for us to contend that our primary task is not this or that. We Christians with our moralisms and petty finger-wagging have done enough damage to our witness in the world and must move to a more constructive task: to show the world what the beautiful and spectacular world was in fact made to be.

1. See proposition 6, note 5, regarding Peter Craigie’s work, whose argument I am relying on here.

2. It is worth noting that numerous twentieth-century academics would decry the “Black Legend” arising out of the sixteenth century that the opponents of Spain would blacken the reputation of Spain and never take account of any of the cultural goods having arisen from Spaniards. Such a move, such academics note, serves a sociopolitical function: decrying the crimes of one’s enemies, noting only their atrocities, makes warring against them more feasible, even desirable. This is an important observation that serves as an illustration of the fact that the demonization of a tradition, party, or ideology that one hates is easy enough and illustrates further why some sort of practice of identifying the principalities and powers, apart from mere reduction to some mortal or national or sectarian enemy (“our enemies are not flesh and blood,” says Ephesians when speaking of the powers), is fundamentally important if we Christians are not to fall prey to the sorts of horrors here decried. Instead, note this: Bartolomé de las Casas was himself both a male European, Spanish, and Christian. Based on his work within the Spanish Christian tradition, a hold-no-punches indictment of the horrors of his fellow men, did Spanish Christians begin to reassess their horrors, for which many had no moral convictions to lead them to question their actions.

3. Dag Hammarskjöld, Markings, trans. Leif Sjöberg and W. H. Auden (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1964), 98.