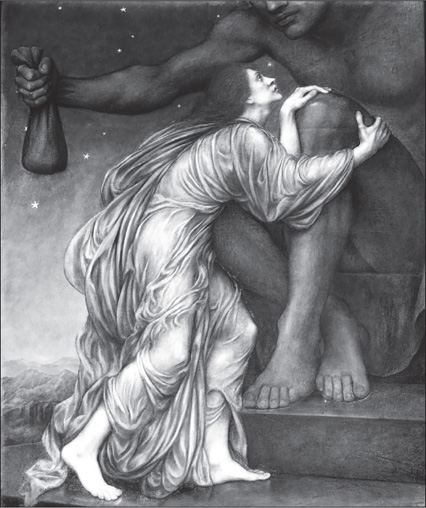

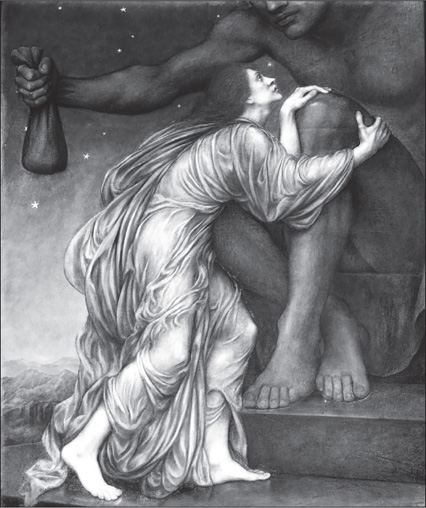

Evelyn de Morgan, The Worship of Mammon, ca. 1909, oil on canvas, De Morgan Centre, London. Wikimedia Commons

Christian Engagement Must Always Be Ad Hoc

SUMMARY

Christian social engagement must always be ad hoc. Given that we live between the time of the inauguration and the consummation of the kingdom of God, there is no ideologically pure or utopian social arrangement among the nations for which we should strive. Any given social structure—no matter its strengths—is prone to fall under the sway of the powers of sin. Once one injustice is corrected with some new practice of equity, the new practice will, in turn, struggle with its own infidelities with regard to greed or pride or coercive force. Then a new corrective must be sought, and then again yet another.

To continue ever to seek such new correctives—gracious and fair and equitable social practices—with patience and peaceableness and truth telling and without coercion or violence or disdain, this is what it means to be living as a Christian, as a Christian community, in the world prior to the consummation of the kingdom of God.

EXPOSITION

Dietrich Bonhoeffer claimed that

Jesus concerns himself hardly at all with the solution of worldly problems. When He is asked to do so His answer is remarkably evasive. . . . Indeed, He scarcely ever replies to men’s questions directly, but answers rather from a quite different plane. His word is not an answer to human questions and problems; it is the answer of God to the question of God to man. His word is essentially determined not from below but from above. It is not a solution, but a redemption.1

But neither did Jesus concern himself with a solution to the problem of cancer, questions about evolutionary theory, responses to environmental degradation, or the grave threat of annihilation by nuclear weapons. Nonetheless, Bonhoeffer rightly reminds us by his words quoted here that Jesus announced the coming of the kingdom of God and inaugurated its presence, and that this reality is indeed a redemption and not a mere solution to human problems. And Bonhoeffer is quite right to insist that the “word,” which is a “redemption,” is indeed what “must first of all be understood. Instead of the solution to problems, Jesus brings the redemption” of humankind, and then “for that very reason He does really bring the solution of all human problems as well.”2

But: it does seem that we must take seriously what the so-called realists have insisted, that we must take seriously that the kingdom come has not yet come fully. In other words, we must not forget that Jesus did not finish what he started—Jesus did not consummate, has not yet consummated the fullness of the kingdom of God—and, so far as the Gospels relate, he left that day and time and deed to the working of God.

We then are left between the times to bear witness through creative solutions to complex problems and ever-shifting realities—ever shifting because of, among other things, the abiding power of sin—from our own distinctive way of life, for the good of the nations.

This simple observation, grounded in a New Testament eschatology, is profound and far-reaching in freeing us from ideological commitments to any given partisan solution to any given problem. If any given institution, party, or policy can (and does) yet fall prey to the power of sin, does yet fall prey to the power of death, then we are always allowed, even required, to do equal-opportunity critique of the institution of the church as much as the institutions of government or other social or economic institutions and structures, and look for ways in which some limited solution in that given context can bear witness to the gracious reign of God broken in but not yet consummated.

Consider the nonideological engagement with centralized governmental power in the biblical story. When the pharaoh has a dream, which the boy Joseph foretells is an omen of a coming great famine, the solution to the problem is a vast project of taxation and centralized bureaucracy. It is through such centralization that the Hebrews are saved, and such a development is celebrated in the telling of the biblical story. Let those ideologically opposed to big government and centralization take note and beware.

And yet, of course, the story does not end there. As the narrative unfolds, the very centralized bureaucracy that was one season a practical solution to a dire social need becomes in the next season the mechanism for enslavement and oppression. When a pharaoh arose “who did not know Joseph,” then that mechanism became the means of the enslavement of the Hebrews it once saved. There is, indeed, a danger to such mechanisms of power, and the danger is put on display in the biblical story. Let those ideologically committed to big government and centralization take note and beware.

In the apostle Paul’s teaching, he depicts the old covenant and the law as a mechanism through which sin can manifest its capacity for oppression. Imagine the freedom that such a realization gives the Christian church in America. If the law of God, given by Moses, can become an apparatus of death, how much more so can American jurisprudence? What then if we realize that the target will always be shifting, and to place too much hope in any given legislative agenda will be a dashed hope?

Take, for example, Michael Lewis’s book Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt. There Lewis documents how well-intentioned and much-needed federal regulation gives rise to an entire financial subculture of high-frequency trading that games the system, taking advantage of that regulation, making billions of dollars out of its own greed. Indeed, Lewis suggests that this dynamic occurs repeatedly in the history of fiscal regulation in the United States. Today’s crisis, emerging out of the dynamics of broken and self-serving impulses, gives rise to new regulation, which becomes the seedbed of the next round of greedily gaming the system.3

To use New Testament language, we might say then that greed—as a systemic corrupt impulse—is indeed subtle and powerful, and no financial regulation will ever be its consummate solution, will ever be its final redemption. Lewis simply illustrates with his indictment of twenty-first-century Wall Street what the apostle Paul knew long ago about the power of law.

Such an observation may allow us greater wisdom in bearing witness to the kingdom of God. We need not become single-issue voters, for example.4 We need not assume one piece of legislation is the only way forward. Those with conservative liberal tendencies, for example, may be opened to appreciate what appears counterintuitive to them: that there is substantive evidence that rates of abortion go down significantly under Democratic presidential administrations in contrast to Republican administrations.5 On the other hand, those with liberal liberal tendencies may be opened to appreciate that care for the poor may be broader than welfare mechanisms that fail to take the development of human virtue seriously.

Evelyn de Morgan, The Worship of Mammon, ca. 1909, oil on canvas, De Morgan Centre, London. Wikimedia Commons

Such an eschatological realism—that the kingdom of God has come, but not yet come in full—need not drive us, as it has so often in Christian history, to set aside the way of Christ.

Does this insistence, though—that Christians seek to submit themselves to the way of Christ in all roles in which they find themselves—mean that Christians really have nothing to say to the powers that be who refuse to take up the way of Christ?

First, this eschatological realism—in which we are constantly attending to the fact that the kingdom of God has come, but not yet fully, and thus (a) all our best attempts at bearing witness to the present-and-coming kingdom are always prone to and always tend toward sin, and (b) that all the best and varied social practices and political commitments are also struggling under the domination of sin and death—allows us to let go the unrealistic idealism or utopianism that drives partisan visions. It allows us to let go of our own nationalisms. This eschatological realism allows us to let ourselves see both the good and bad of any given party, any given nation-state. We must continue to insist that Christians are not utopian idealists. This is true precisely because our vision of history and life is informed by such eschatological realism. Christians who strive to live by the Sermon on the Mount (rightfully understood, of course) are not the idealists and utopians. It is the ideologues, the partisans, the nationalists who are the dangerous utopians. It is this utopianism that sows the seeds of hostility and reaps a warring madness.

No social structure—including the church and the members of the church—will transcend the detritus of death prior to the consummation of the kingdom of God. This position is not pessimism. It is grounded in an eschatological hope, a hope already breaking into our midst. Nor is this position cynical, because it is not interested in judging others. It is interested in making concrete and specific contributions of service to the world that simultaneously take seriously the deep brokenness of all things.

Second, this approach then makes space for political realism: not in granting such political realism status as authoritative for ethics or policy or Christian life, but in its capacity to see things, to see power dynamics at play that we may not be able to see otherwise. Political realism stereotypically avoids utopian or idealistic visions of politics, with a deep awareness of the depths to which the human hankering after power stoops. Its solution—of a moderated self-interest, always balancing power with counterpower—cannot well serve Christian ethics because it replaces the normativity of Christ with the normativity of the self-interest of nation-states, rulers, or some select group to the exclusion of others. But its insight regarding power dynamics may serve us. First, in being an ally with Christians to critique the nationalists and utopians; and second, in helping Christians understand the deep working of power and self-interest in the world.

We must make clear our insistence on taking seriously the way of Christ—even granting that we are always falling short, always needing to repent again—our insistence on upholding the way of Christ as our norm for our lives. But as seen, this does not mean we have nothing to share with the unbelieving social orders that cannot or will not accept Christ as Lord. This can be true if and only if the social practices of the gospel are indeed in line with the grain of the universe, only if the social practices of reconciliation and sharing and truth telling and forgiveness are in fact consistent with the fundamental nature of being human.

We do believe and proclaim that they are. Consequently, there is a great and broad playing field in which we may make contributions. We can seek solutions to concrete human problems, whether medicinal or social or political or economic, and offer these as good news to our communities. We may do social science research to find constructive ways to deal with the opioid epidemic that are superior, more effective, and less costly than those of the criminal justice system, and help liberal liberals and conservative liberals alike see how such solutions may satisfy both their deepest concerns. We may contribute from our studies in nonviolence such means that may be used in community policing to minimize the use of force, especially lethal force, and thus the hostility that is threatening many of our communities. We may pursue neurological research that promises new possibilities in understanding the cultivation of various social virtues such as compassion, self-control, and empathy, which may make possible holding together tenuous and fragile bonds of community. We may seek to map the human genome and beat the capitalists to their own mapping so that such knowledge might be in the public domain and thus accessible to a broader swath of humankind.6

And we may, on the side of critique, call rulers, even tyrants and despots, to change and take steps in the direction of the kingdom of God. That is, even if they refuse to acknowledge the authority of Christ, we may still bear witness to the beauty of truth or goodness and call them to take such seriously. For example, the tyrant can be called to repent of his lying and self-aggrandizement and violence, especially to the degree that these poison the community. For some, the step away from lying and into truth telling will be as great as an unbeliever stepping into a confession of faith. We should not take lightly the potential consequences power brokers may face when we ask them to tell the truth or stop their violence or welcome the stranger.

As Christians we would have all people—statesmen, presidents, queens, and kings—submit to the way of Christ. This would be, undoubtedly, a dangerous proposition for a president or king or queen: to love one’s enemies, to forgive debts, to refuse to do to them what they have done to us. All this would be highly dangerous for a leader of a nation-state. It may get him or her killed, and certainly could get him or her thrown or voted out of office. Such consequences, however, are the dangers of public leadership generally considered. One may get thrown out of office, not voted back into office, or assassinated for many other reasons than seeking to submit to the way of Christ while in office.

But even if they will not or cannot take up the lordship of Christ, there will remain many constructive steps toward the liberating ways of the kingdom of God. And it is those next steps, those next dangerous, risky steps toward such liberation, to which we seek, winsomely, to call the as-yet-unbelieving ruler.

Such an approach grants us immense liberty—liberty, we might hopefully note, much greater than the bondage of party affiliation apparently affords Washington politicians. In strategic fashion—“be wise as serpents and innocent as doves”—we can, and should, look for places of common cause, of moves in the right direction, and celebrate and facilitate such moves.7

Our own proleptic living—trusting that the magnificent Spirit of God makes possible impossible possibilities, even now—allows us to go forth and sow the seeds of the kingdom of God, knowing that history is not one damn meaningless thing after another but the stage for the brilliant inbreaking of the final hope of God. It will not be the hope of America; it will not be the hope of any nation-state. It will be the hope of the Christ who breaks down all walls of hostility, making all things new, for captivity has, after all, been taken captive and death already undone.

1. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Ethics (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1955), 350.

2. Bonhoeffer, Ethics, 350.

3. Michael Lewis, Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt (New York: W. W. Norton, 2015).

4. Note my care in language. I am not suggesting there would never be a time or context in which being a single-issue voter would be out of bounds. I am suggesting instead that we need not presume that one piece of legislation might be the panacea we expect, after all, and thus other ways forward are made available to us.

5. See T. C. Jatlaoui et al., “Abortion Surveillance—United States,” Surveillance Summaries 67, no. 13 (2018): 1–45, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/ss/ss6713a1.htm.

6. I heard Francis Collins, who led the Human Genome Project, recount that this was one of the driving forces behind his own (Christian) commitment to helping map the human genome as a part of the publicly funded pursuit he was a part of.

7. At the same time, our theologically prioritized social critiques may provide helpful and needed correctives to the political philosophers who often begin with what they believe can be commonly known.