[270] In spite of his obvious duality the unity of Mercurius is also emphasized, especially in his form as the lapis. “In all the world he is One.”1 The unity of Mercurius is at the same time a trinity, with clear reference to the Holy Trinity, although his triadic nature does not derive from Christian dogma but is of earlier date. Triads occur as early as the treatise of Zosimos, περì ἀρετῆς (Concerning the Art).2 Martial calls Hermes omnia solus el ter unus (All and Thrice One).3 In Monakris (Arcadia), a three-headed Hermes was worshipped, and in Gaul there was a three-headed Mercurius.4 This Gallic god was also a psychopomp. The triadic character is an attribute of the gods of the underworld, as for instance the three-bodied Typhon, three-bodied and three-faced Hecate,5 and the “ancestors” (τριτοπάτορες) with their serpent bodies. According to Cicero,6 these latter are the three sons of Zeus the King, the rex antiquissimus.7 They are called the “forefathers” and are wind-gods;8 obviously by the same logic the Hopi Indians believe that snakes are at the same time flashes of lightning auguring rain. Khunrath calls Mercurius triunus9 and ternarius.10 Mylius represents him as a three-headed snake.11 The “Aquarium sapientum” says that he is a “triune, universal essence which is named Jehova.12 He is divine and at the same time human.”13

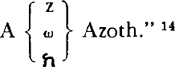

[271] From all this one must conclude that Mercurius corresponds not only to Christ, but to the triune divinity in general. The “Aurelia occulta” calls him “Azoth,” and explains the term as follows: “For he is the A and O that is everywhere present. The philosophers have adorned [him] with the name Azoth, which is compounded of the A and Z of the Latins, the alpha and omega of the Greeks, and the aleph and tau of the Hebrews:

The parallel with the Trinity could not be more clearly indicated. The anonymous commentator of the “Tractatus aureus” puts the parallel with Christ as Logos just as unmistakably. All things proceed from the “philosophic heaven adorned with an infinite multitude of stars,”15 from the creative Word incarnate, the Johannine Logos, without which “was not any thing made that was made.” The commentator says: “Thus the Word of renewal is invisibly inherent in all things, but it is not evident in elementary solid bodies unless they have been brought back to the fifth, or heavenly and astral essence. Hence this Word of renewal is the seed of promise, or the philosophic heaven refulgent with the infinite lights of the stars.”16 Mercurius is the Logos become world. The description given here may point to his basic identity with the collective unconscious, for as I tried to show in my essay “On the Nature of the Psyche,”17 the image of the starry heaven seems to be a visualization of the peculiar nature of the unconscious. Since Mercurius is often called filius, his sonship is beyond question.18 He is therefore like a brother to Christ and a second son of God, though in point of time he must be accounted the elder and the first-born. This idea goes back to the conceptions of the Euchites reported in Michael Psellus,19 who believed that God’s first son was Satanaël20 and that Christ was the second.21 However, Mercurius is not only the counterpart of Christ in so far as he is the “son”; he is also the counterpart of the Trinity as a whole in so far as he is conceived to be a chthonic triad. According to this view he would be equal to one half of the Christian Godhead. He is indeed the dark chthonic half, but he is not simply evil as such, for he is called “good and evil,” or a “system of the higher powers in the lower.” He calls to mind that double figure which seems to stand behind both Christ and the devil—that enigmatic Lucifer whose attributes are shared by both. In Rev. 22 : 16 Christ says of himself: “I am the root and the offspring of David, the bright and the morning star.”

[272] One peculiarity of Mercurius which undoubtedly relates him to the Godhead and to the primitive creator god is his ability to beget himself. In the “Allegoriae super librum Turbae” he says: “The mother bore me and is herself begotten of me.”22 As the uroboros dragon, he impregnates, begets, bears, devours, and slays himself, and “himself lifts himself on high,” as the Rosarium says,23 so paraphrasing the mystery of God’s sacrificial death. Here, as in many similar instances, it would be rash to assume that the alchemists were as conscious of their reasoning processes as perhaps we are. But man, and through him the unconscious, expresses a great deal that is not necessarily conscious in all its implications. Nevertheless I should like to avoid giving the impression that the alchemists were absolutely unconscious of their thought-processes. How little this was so is proved by the above quotations. But although Mercurius, in many texts, is stated to be trinus et unus, this does not prevent him from sharing very strongly the quaternity of the lapis, with which he is essentially identical. He thus exemplifies that strange dilemma which is posed by the problem of three and four—the well-known axiom of Maria Prophetissa. There is a classical Hermes tetracephalus as well as the Hermes tricephalus.24 The ground-plan of the Sabaean temple of Mercurius was a triangle inside a square.25 In the scholia to the “Tractatus aureus” the sign for Mercurius is a square inside a triangle surrounded by a circle (symbol of totality).26