DOUGLAS COOPER

Douglas Cooper and Picasso at La Californie, Picasso’s villa at Cannes, 1961

There was one point about himself that Douglas Cooper always made very, very clear: he was not Australian. True, his antecedents—who were traders, not convicts—had sailed away to Sydney early in the 1800s and had made an enormous fortune by the middle of the century. The Coopers ended up owning much of the soon-to-be prosperous Woollahra section of Sydney; they were also the biggest shippers of gold in Australia. Douglas’s great-grandfather became a member of Parliament and Speaker of the House of New South Wales in 1856 and was made a baronet in 1863 (Sir Daniel Cooper of Woollahra). From then on he spent as much time in England as he did in Australia, eventually settling permanently in London, where he died. His son and grandson followed his example. To Douglas’s eternal rage, the Cooper family sold their Australian holdings sometime in the 1920s. Given his and his father’s lifelong possession of British passports and his mother’s Dorset lineage, Douglas understandably resented his countrymen’s tendency to endow him with an erroneous—i.e., Australian—provenance. (“My parents visited Australia on their honeymoon,” he said, “so I may have been conceived there, but that’s the closest I ever got.”) A further irritant: his money was wrongly assumed to derive from Cooper’s sheep dip, hence the jokes about Australian sheep bleating “Bra-a-a-que.” A very minor matter, one might have thought. Unfortunately, resentment made for paranoia; paranoia made for Anglophobia; and Anglophobia made for the outlandish accents, outré clothes, and preposterous manner that Douglas cultivated. There was also a hint of paradox to his behavior. Douglas’s idées fixes only made sense if they were turned upside down, or seen in the light of willful provocation or perversity. Anglophobia was the only form of patriotism that Douglas could permit himself.

Juniper Hall, 1995, Woollahra, Sydney; one of the properties of DC’s great-grandfather Sir Daniel Cooper of Woollahra

The vehemence that was to have such a corrosive effect on Douglas’s character was a legacy from his father, “Artie” Cooper, a bowler-hatted major who radiated disapproval. In the father’s case, vehemence was compounded by stupidity; and in the son’s case, it was mitigated, some of the time, by intelligence. “My father did absolutely nothing with his life,” Douglas told me, “except live off his considerable fortune, vent his temper on anyone who disagreed with him, and atone by indulging in a lot of Masonic mumbo-jumbo.” To his shame, Douglas, who set great store by men’s looks, had inherited his father’s scary little avian eyes. In most other respects he looked like his homely, much-put-upon mother, who was as cozy and plump as a cottage loaf.

Mabel Cooper came of a long line of backwoods baronets that God had all of a sudden decided to terminate. In the space of two years (1941–42), the Smith-Marriotts’ handsome Dorset seat, the Down House, had been commandeered by the army and burned to the ground; and then the last two baronets—Mabel’s dissolute, horsy, bachelor brothers (one of them aptly named after his Wyldbore antecedents)—died within a year of each other. So did their spinster sister, Dorothea. Almost everything went in death duties. To the family’s dismay, Dorothea turned out to have left her mischievous nephew the beautiful neglected arboretum at the core of the Down House estate in the hope, Douglas could only imagine, that he would do something dreadful and nondendrological with it—something that would upset the other Coopers. For once, Douglas behaved impeccably—maybe he felt he was being set up—and chose to sign over the arboretum to the other heirs. He had not always been so easy on his parents. To get back at them for trying to steer him into one boring profession after another—diplomacy, accountancy, the law—when he wanted only to study art history, Douglas had played cruel tricks on them. Shortly before the war, he had telephoned his mother in an assumed voice, claiming to be a detective-inspector. “I regret to inform you that your son has committed suicide. We will have to ask you to identify the body.”

Douglas had two younger brothers. The elder, Geoffrey, was the object of his intense loathing for having made off with the wine he had left in storage when he was away at the wars. Douglas sued and won, and thereafter claimed that the only way of communicating with his “crooked sibling” was by writ. He liked his younger brother, Bobby, well enough, although he had once dangled him as a baby over the stairwell of the Coopers’ large Eaton Place house, and had to be talked out of dropping him onto the stone floor fifty feet below by his beloved nanny: “You’ll have to clean up the mess, master Douglas.” After being badly wounded during the war, Bobby had endeared himself to Douglas by marrying Princess Teri of Albania, a daughter of the former King Zog’s eldest sister, Princess Adili. Asked by his mother about Muslim wedding customs, Douglas told her to “take up the carpets and hang them out of the windows; it will cheer up Eaton Place no end.” When Douglas took me to visit his brother, who farmed the Down House estate, he could not resist making trouble. Suspecting that Princess Adili was kept hidden, he went in search of her and, according to him, found her stirring away at a cauldron—“a noxious goat-tail stew, my dear.” After scolding Bobby for banishing his royal mother-in-law to the kitchen, he insisted we take our leave—“before they ask us to stay for dinner.”

Although his parents were excessively philistine (a bad Bouguereau was a prized possession), there was a family precedent for Douglas’s involvement in the arts. A bachelor uncle, Gerald Cooper, had been a musicologist and spent most of his fortune collecting Purcell manuscripts and memorabilia. On his death, Gerald left this archive to his friend Edward Dent, the leading expert in the field, to distribute as he thought fit, an act that scandalized the Coopers. The archive was very valuable, and, worse, it transpired that Gerald, like Dent, had been gay. Douglas owed more than he liked to admit to his uncle, who had taken him, when he was twelve or thirteen—that is to say, in the mid-1920s—on a trip that would have a formative effect on his taste: to Monte Carlo, where the Diaghilev company was performing. Memories of the ballets Douglas saw on this occasion came in useful fifty years later, when he wrote his book Picasso Theatre. Gerald Cooper was also a patron of contemporary music, and he saw to it that his nephew developed an ear for Stravinsky, Webern, and Bartók as well as the classics. When Douglas went to Repton—a school he loathed, especially a master (subsequently Archbishop of Canterbury) whom he accused of converting him to atheism—he was well placed to enjoy the concerts that his uncle organized in nearby Derby.

Nicholas Lawford, the British diplomat, who ended up sharing a house on Long Island with the fashion photographer Horst, and who had known Douglas at Repton as well as Cambridge, remembered him as “a Botticelli angel” who was much more sophisticated than the other boys. It was not until Douglas went up to Cambridge in 1929 that he became a rebel, an aesthete, and an exhibitionist who sported an Elizabethan cane dangling with pompons. “Very flamboyant he was,” Nicholas said. “I believe I once chased him round the court with a hunting crop.” At Cambridge he was known to many as “Cousin Douglas,” because so many of his contemporaries—Pennys, Bankses, Wyldbore-Smiths, Wingfield-Digbys—were cousins of his mother’s. In later years Douglas chose to lose touch with these cousins—“much too British, my dear”—or was it the cousins who chose to lose touch with him? After a year or so, Douglas removed himself from Cambridge. He seems not to have been sent down but to have left of his own volition to study art history, which was not as yet possible at Cambridge. There was, however, a rumor that a landlady had got him into trouble for draping the reproduction of a Raphael madonna above his bed in his black silk pajamas.

In London, 1941: DC’s father (in top hat) next to Bobby Cooper; DC and his mother at far right

At the age of twenty-one, Douglas had come into a trust fund of £100,000 (the equivalent then of about $500,000). Today this would not generate the price of a Picasso drawing, but by the standards of 1932, Douglas was rich. Money meant that he could flout his father and devote himself to art history (at the Sorbonne and Marburg-in-Hessen) and—no less horrifying to his family—the pursuit of cubist works of art and good-looking young men.

Douglas began his professional career with an experimental stint as an art dealer. It was not a success. He had bought a share in a gallery belonging to an acquaintance, Freddy Mayor—a most genial man, but hardly the right partner for an uncompromising modernist. Freddy was short, stout, and rubicund. He was a racing man and a ladies’ man, and he greatly enjoyed getting drunk with the chaps. He liked modern art well enough, although, to believe Douglas, he could not tell the difference between a Braque and a Bruno Hatt (the spoof abstractionist foisted by Evelyn Waugh’s friends on London’s art world). Freddy catered to his own ilk—sporting bons vivants who fancied a spot of fauve color on their walls—and felt ready to risk a bet on Matisse, as if he were a promising outsider in the Grand National.

Douglas had a more serious agenda. With the help of such avant-garde Parisian dealers as D. H. Kahnweiler and Pierre Loeb, he hoped to put on small shows of current work by Picasso, Léger, Miró, and Klee, but there were few takers. Freddy played it safe and did better. Mutual dislike and distrust doomed the partnership from the start. Douglas made the break as painful as he could. He withdrew his backing at a time when the bookies had left his partner more than usually short of funds. In lieu of cash, he ended up with much of the stock, including a lot of Mirós.

With some justice, Douglas blamed his failure as a dealer on what he called “ghastly English philistinism,” as epitomized by the Tate Gallery (the only museum in London mandated to acquire contemporary art). He and only he, Douglas felt, was qualified to make acquisitions for the modern part of the Tate. He was probably right. With him on the staff, this fuddy-duddy institution would have given New York’s Museum of Modern Art a run for its money. And so Douglas applied for a job there—unsuccessfully. The Tate was administered by the Treasury, the staff were civil servants, and they had no intention of employing anyone as intransigent as Douglas. Nevertheless, he continued to harbor illusions: “Somebody had to stop those feeble hacks at the Tate buying all that genteel British rubbish.”

Douglas thought there might be a change for the better in 1938, when the then director, J. B. Manson, made a drunken fool of himself and had to be fired. His replacement, John Rothenstein, turned out to be just as disastrous. Manson may have been a clown, but Rothenstein was a toady, a smug chauvinist with a distaste for modern art. If eventually he came around to adulating Francis Bacon, it was out of expedience, but the conversion did not enhance his record or his credibility. I had reason to share Douglas’s dislike of the Rothenstein family. As an art student, I had suffered from the dismal teaching of John’s father, Sir William Rothenstein, and his inept uncle, Albert Rutherston (head of Oxford’s Ruskin School, where the Slade School of Art took refuge during the war). We students were not bothered by Rutherston’s ineptitude so much as his insistence that we work from a nude model, said to be his mistress. She was pretty enough, but seemingly afflicted with Saint Vitus’ dance. “The moving target,” we called her. When her wiggling became intolerable, some of us in the life class would hum a song from a wartime revue: “I’m a nude on the dole / struck off the roll / because I couldn’t keep still….”

Douglas’s rage at the lack of response on the part of Rothenstein and the Tate trustees to fauvism, cubism, and surrealism, the fundamental cause of what would come to be called “the Tate Affair,” was a catalyst for his own collection—a collection that would show up the Tate’s modernist holdings as shamefully inadequate. He set aside a third of his inheritance and by the time World War II broke out had acquired some 137 cubist works, a number of them masterpieces. He was lucky in that he had very few rivals in the field, and prices for cubist works had remained amazingly low. Of the four artists in Douglas’s cubist pantheon, only one, Juan Gris, had died. The other three—Picasso, Braque, and Léger—were very much alive and very hard at work. Léger was especially delighted to have an enthusiastic new patron—one, moreover, who wanted to write about his work. He and Douglas remained friends for life. Braque, too, was pleased to find a collector intent on charting his cubist development, phase by phase, year by year. At first Douglas made little headway with Picasso. The artist already had a young British collector in his entourage, Roland Penrose, scion of a rich Quaker family, who had recently joined the Surrealists. Penrose had met Picasso through Paul Eluard, the artist’s poet laureate. Eluard proceeded to sell Penrose the numerous works that Picasso had contributed to the poet’s support. Just as Eluard had made his wife, Nusch, available to Picasso, Penrose offered up his future wife, Lee Miller, the American photographer, to the artist, when they all spent the summer of 1938 together in the same hotel at Mougins. In view of Douglas’s competitiveness, Roland did not encourage Picasso to include him in his predominantly Surrealist circle.

Fifteen years later, the dynamics would change. By going to live in the south of France, Douglas saw rather more of Picasso than Roland did. This would make for epic resentments, which the artist enjoyed fanning. The two Englishmen were very competitive about each other’s collections. Douglas dismissed Roland’s as “ready-made.” “I don’t call it collecting,” he used to say, “if you combine Picasso’s handouts to his Surrealist friends with a collection bought lock, stock, and barrel from a Belgian.” True, Roland had acquired René Gaffés collection en bloc; however, Douglas had done a similar thing, only on a much bigger scale.

DC, Ingeborg Eichmann, and G. F. Reber in the Swiss Alps, 1937

Most of the finest paintings that Douglas amassed between 1932 and 1939 came from a single source: a shadowy German called G. F. Reber. Reber lived lavishly, if somewhat precariously, in a château outside Lausanne filled with by far the largest collection of cubist and post-cubist art in private hands. Douglas did not like to admit that it was Reber’s example he had followed when he limited his acquisitions to works by the four great cubists. In other respects their approach to collecting was very different. Whereas Reber was an art investor, a stockpiler of modern masterpieces, Douglas was an art historian out to chart in depth the work of the four creators of cubism, subject by subject, medium by medium, year by year. And what he wanted from his collection was not financial advantage but recognition—or better still, fame.

DC with the brilliant Berlin art dealer Alfred Flechtheim, Paris, 1937

Today Reber is forgotten, but in the 1920s and early 1930s he was one of the biggest players in the field of modern art. Born to an impoverished Protestant minister in the Ruhr, he had made enough money out of an early venture in textiles to indulge his passion for post-impressionist painting. Marriage to a rich, cultivated wife enabled him to splurge even more. By the age of thirty, in 1910, he had assembled a superb group of twenty-seven Cézannes, as well as works by van Gogh, Gauguin, Courbet, Degas, Renoir, and Manet. Besides collecting art, Reber was fascinated by magic and mysticism. That he was also a leading Freemason might explain the Communist Spartacists’ attempt to arrest or kidnap him when they broke into his house in 1919. In fear for his life, Reber fled Germany for Switzerland, where he eventually settled in some splendor in the Château de Béthusy at Lausanne. In the early 1920s Reber modernized his collection. Out went the impressionists and post-impressionists (with the exception of Cézanne’s Boy in a Red Waistcoat), and in came the great Picassos (some sixty of them), sixteen Braques, eleven Légers, and eighty-nine Juan Grises. It was by far the largest and finest ensemble of its kind. Douglas would skim much of the cream off it.

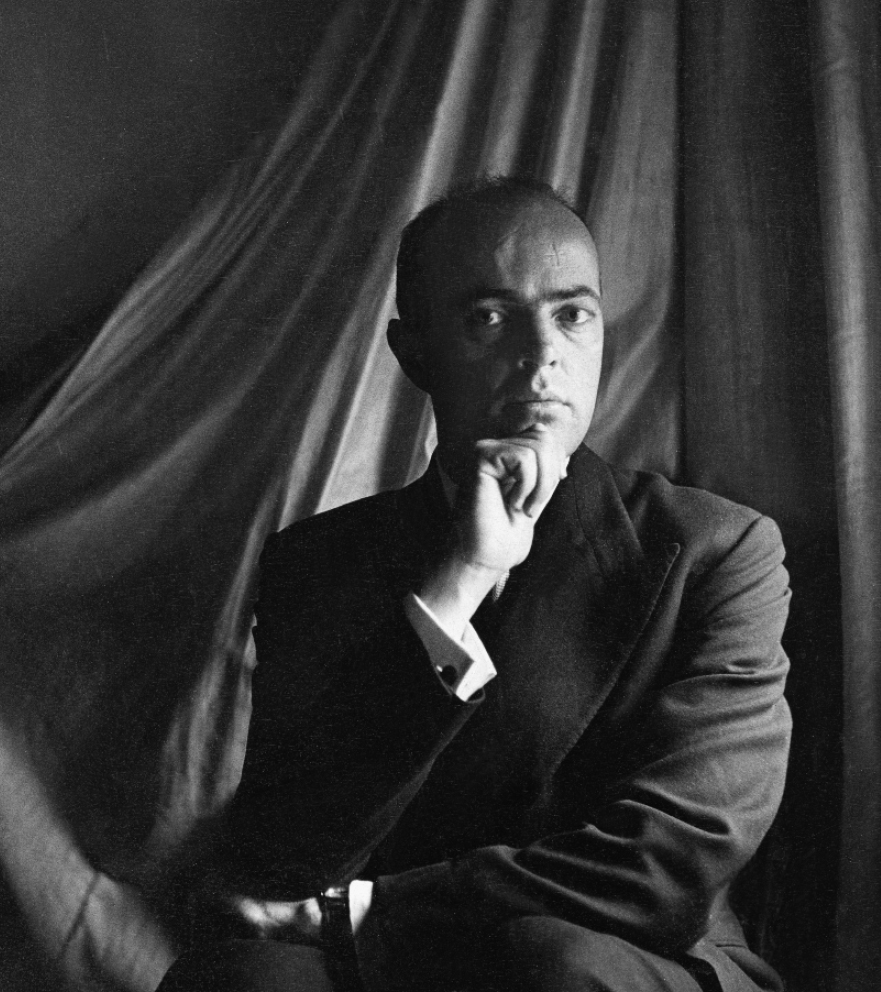

DC at age twenty-seven, in New York, 1938

Douglas and Reber came into each other’s lives around 1932, at an opportune time for both of them. Heavy losses on the Paris Bourse in 1929 had transformed the man who had been the most adventurous art investor of the 1920s into a panic-stricken unloader. And so a young collector who had the means as well as the courage to live up to his modernist convictions was very welcome. For his part, Douglas would take full advantage of the fact that Reber was broke—so broke that he had had to use many of his remaining paintings as collateral for loans. The greatest Picasso that Douglas ever acquired, the 1907 Nudes in the Forest (now one of the glories of the Musée Picasso), had to be redeemed from the municipal pawnshop in Geneva for £10,000.

The Hon. Sholto MacKenzie (later Lord Amulree)

Reber hoped to extract a further favor from Douglas. Some years earlier his daughter, Gisela, had brought home a school friend—a bright, attractive girl from the Sudetenland, Ingeborg Eichmann. Ingeborg was well off—her family manufactured the paper on which Czech banknotes were printed—and, like Douglas, she aspired to study and collect modern art. Reber made her his mistress and, over the years, sold her a number of fine modern paintings. The centerpiece of her collection was Picasso’s cubist masterpiece, the 1913 Seated Woman (which would fetch $21 million in the 1997 Victor Ganz sale). Since Ingeborg and Douglas liked each other well enough and shared a passion for cubism, Reber tried to manipulate them into marriage. It would be a union of kindred spirits, which would engender paintings rather than babies. More to the point, a British passport would save Ingeborg from the curse of being born in a part of the world that involved successive changes of nationality. (The Sudetenland was Austrian until 1918, Czech until 1938, German until 1945.) True, marriage might have made Douglas appear less homosexual—still a stigma in the 1930s—but that is not necessarily what he would have wanted. Far from concealing his orientation, he consciously or not flaunted it. Like Francis Bacon he was not above using vitriolic camp as a weapon. And then, fond as he was of Ingeborg, Douglas was physically terrified of women—all the more reason not to saddle himself with a bride for the greater convenience of an art investor who could not afford to leave his wife.

In 1938, Douglas and Ingeborg left for the United States, where they made a prolonged tour of American museums and private collections. While they were on the other side of the Atlantic, Chamberlain and Daladier allowed Hitler to annex Czechoslovakia. Ingeborg was not Jewish, but she had no intention of living under the Nazis. And since Douglas was not prepared to marry her, she became stateless in her own country. Ingeborg was not one to bear a grudge. She realized that marriage, even if in name only, would have left Douglas feeling threatened. Despite his misogyny, he could be very fond, even jealous, of his women friends, but woe betide them if they made undue demands or tried to move in on him. Ingeborg never did, and remained a friend for life.

Sometime in the early 1930s, Douglas had embarked on a lifelong relationship with a handsome Scotsman some ten years older than himself. To most people he was known as Sholto MacKenzie. Douglas found this too much of a mouthful and called him Basil. Basil called him Dougal, as would many of his friends. Basil’s father had been one of four sons of a Lowland Scottish farmer. The eldest remained a farmer; the second son invented the cardiogram; the third became a minister; and the fourth, Basil’s father, a liberal politician and lawyer, was raised to the peerage. Basil inherited the title in 1942, whereupon Douglas would usually refer to him as “our Lord.” Basil might have followed his father into the law, but he suffered from a terrible stammer, and so he became a doctor like his very distinguished uncle James. On the side he was an amateur historian; he also devoted much of his time to being Douglas’s gofer. For his part, Douglas was totally reliant on Basil’s gyroscopic steadiness. He would write him at considerable length once or twice a week, over a period of close on fifty years. Alas, this correspondence, which was returned to Douglas after Basil’s death, seems to have disappeared.

Unlike Douglas, Basil was a man of exemplary virtue: dutiful, thoughtful, a good companion. Far from remonstrating with Douglas for his outrageous behavior, this gentle, repressed Scot would end up living vicariously through it. Paradoxically, he would get a far bigger kick out of “bad” Douglas—the flamboyant fiend who was the scourge of the art world—than out of “good” Douglas, the conscientious art historian who was good with students and impressionable art lovers provided no one challenged him. I suspect that Douglas’s rage served as a catalyst for the rage that this exemplary Scotsman had suppressed so rigidly that it boiled up only in the form of his seismic stammer. In an effort to mouth words beginning with b (“bugger” was apt to be a problem), Basil would turn pink and shake until the monocle popped out of his eye socket.

Basil and Douglas were indefatigable sightseers. Whenever Basil could escape his multifarious duties, they would go off on architectural tours—Romanesque churches, Palladian villas, Crusader castles. In the summer of 1938, they were motoring back from the south of France with a young stockbroker in tow, when Douglas fell asleep at the wheel and crashed into a tree on the Route Nationale 7. His companions were unscathed, but Douglas’s face was smashed up. He regained consciousness in a hospital at Moulins, just in time to prevent the nuns from removing one of his eyes. Instead he had himself driven to Zürich and delivered into the hands of the famous Dr. Voigt. This philanthropic man overcharged the rich so that he could afford to undercharge the poor. However, when the mood was on him, Voigt turned into a sadistic maniac: out the eye must come, and no nonsense about anesthetics. Douglas would never forget the horror of the doctor’s morning visits, when he would gleefully plunge a hypodermic needle directly into his damaged pupil. A corneal graft did not restore his sight, but left the eye looking more or less normal. Anyone who peered deep into Douglas’s sharp little eyes would be disconcerted to discover that the pupil of the sightless one was shaped like an inverted keyhole—a disturbingly Magritte-like effect. The accident left Douglas prey to appalling headaches and nervous depressions, which his wartime experiences would do much to exacerbate.

Douglas was twenty-eight when World War II broke out. Delighted that his injury exempted him from serving in the British army, he left London for Paris and joined a small, fashionable ambulance unit organized by the waspish, Charlus-like art patron Count Etienne de Beaumont. Etienne had commissioned works from Picasso and Braque and Satie. He had also been the inspiration of Raymond Radiguet’s novel Le Bal du Comte Orgel. The very grand costume balls the Beaumonts gave in their very grand hôtel particulier (both Proust and Picasso had been guests at the 1921 ball) were prompted as much by chic and spite as hospitality. To keep their guests guessing, the Beaumonts made a point of not inviting two or three especially vulnerable friends. An excellent principle, Douglas said. “One should always keep one’s friends and loved ones on their toes.”

For Douglas—as for Jean Cocteau, twenty-five years before—Etienne was something of a beau idéal. He saw himself playing the same sort of role in Etienne’s ambulance unit that Cocteau had played in it in World War I, when he had been put in charge of the portable showers and, to the rage of a jealous sergeant, had fallen in love with a Moroccan sharpshooter. If Etienne had not intervened, the poet might have been murdered. And then there had been trouble in 1915, when Etienne and Cocteau had set off for the Western Front and stopped for the night at the first available hotel. Before dinner they had gone upstairs to slip out of their Poiret-designed uniforms into something less martial: silk pajamas, one black, one pink, and jangling ankle bracelets. Unfortunately their hotel turned out to be the headquarters of the British High Command, and when they made their entry into the dining room, Lord Haig’s staff made their homophobia felt.

Twenty-five years later, Douglas was a bit more circumspect. In the winter before the German breakthrough, Etienne used his ambulances as mobile libraries to deliver books and magazines to the Maginot Line, and also for casual pickups. In the course of his duties, Douglas fell for a “faun-like” soldier who had slithered through the mud to grab a library book from him. The mud, Douglas said, made the encounter all the more romantic. The two of them remained in touch. After the war, the “faun” came to stay in London, dumped Douglas for someone younger and handsomer at a party at Viva King’s, and gave him the watch that Douglas had just given him.

When battle was finally joined in June 1940, Douglas entrusted two recently purchased Picasso pastels to the concierge at the Ritz (who, amazingly, returned them to him, only slightly foxed, four years later) and went into action. He turned out to be an extremely cool and effective ambulancier. Disaster evoked his courage and steeliness. Despite strafing by German planes and panic-stricken refugees blocking all roads to the south, Douglas and his co-driver, C. Denis Freeman, brought their quota of wounded safely to Bordeaux, where a British destroyer waited to take them to Plymouth. Their book about these experiences, The Road to Bordeaux, portrayed the mass stampede so vividly that the Ministry of Information used excerpts for an anti-panic leaflet.

For accomplishing this mission, the French awarded Douglas the médaille militaire. The British packed him, as well as Freeman, off to Liverpool, where they were detained. Because he had no papers, wore an odd French uniform, and behaved in an autocratic way, Douglas was assumed to be an impostor or a spy. A day or two passed before a friend discovered where he was, established his identity, and got him released. Although he treated his detainment as a laughing matter, Douglas never forgave the “ghastly English” for it. They would pay for it, he always said, and pay for it they did. This was another justification for leaving none of his paintings to a British institution.

If Douglas was still determined to “do his bit,” this was not so much for crown and country as to defeat the fascist foe. Many of his art-historian friends had gone to work as spy-catchers or code-breakers at Bletchley Park. Douglas’s linguistic skills would have qualified him for this work, but those in charge may have felt that he was too volatile for a hush-hush organization. In the end Basil prevailed upon his father to get Douglas a commission in air force intelligence. Poking around in the wreckage of shot-down German planes and investigating the burned bodies of the pilots was his first assignment. For someone as fastidious and high-strung as Douglas, this was acutely nauseating. He would never get over “the macabre barbecue smell of newly charred flesh.” Douglas was good at pulling strings, however, and soon had himself transferred to the infinitely more congenial task of interrogating prisoners of war.

Douglas’s “evil queen” ferocity, penetrating intelligence, and refusal to take no for an answer, as well as his ability to storm, rant, and browbeat in Hochdeutsch, dialect, or argot, were just the qualifications that his new job required. As soon as the Allies began to push the Germans back into Libya, the RAF packed him off to Cairo to grill high-ranking officers. Torquemada could hardly have done better. By alternating threats with cajolery—softening-up dinners at Shepherd’s Hotel—he managed to manipulate many a susceptible prisoner into blurting out where in the desert Rommel had hidden his matériel. On overhearing Douglas’s high-pitched interrogation of some wretched Hun, an Air Vice Marshal on a tour of inspection expressed surprise: was the RAF using women interrogators? Douglas also did some spy-chasing, and had fun monitoring the activities of a pro-German belly dancer in a houseboat on the Nile.

Cairo during the North African campaign was much to Douglas’s taste. There were ancient monuments to be visited and approved or written off. (On the whole, he preferred Islamic and Coptic art to dynastic Egyptian—“all those clones in profile”.) Also, social life was extremely convivial and, as usual in wartime, dissolute. Old friends in the forces were always turning up on leave. And then, he got on well with the Cairenes—everyone from archeologists to a gay old cousin of the king who lived in a seedy Second Empire palace “which hadn’t received a lick of paint since the opening of Aida.” He also loved Alexandria, not least the Cavafyish hustlers. Alexandrines, he said, were far more pampered and decadent than Cairenes. One effete bachelor would give parties at which guests were assigned to first- or second-class salons, according to their looks, wealth, or social position, and titillated with glimpses of the host’s yellow diamond collection. Another Alexandrine dandy would not wear the shoes that Lobb had made for him until he had tested them by bowling them the length of his ballroom; shoes that failed to end up toe-first went back to the maker. Douglas was fascinated but appalled by the beau monde, as was a prewar friend of his and Francis Bacon’s, Patrick White, the Australian novelist and future Nobel laureate. White, who was also in air force intelligence, had recently embarked on a lifelong relationship with Manoly Lascaris, a cultivated and charming Alexandrine Greek whose impoverished family could trace its origins back to Byzantium. Douglas was envious. Why couldn’t he find someone like that?

And then, all of a sudden, Douglas’s career as an interrogator came to an end. Exactly what happened is unclear. Thanks to hints dropped by Douglas in a rare confessional mood and scraps of corroboration from Basil, I believe I have been able to reconstruct what happened. An attractive German officer—senior in rank but young in years—came up before Douglas for interrogation. He was thought to know the whereabouts of tanks or planes or ammunition dumps. In the course of grilling the prisoner—playing on his anti-Nazi or, possibly, homosexual feelings as well as doing him favors—Douglas fell for the man. Whether or not this enhanced his interrogatory powers, he managed to break him. After spilling the precious beans, the officer hung himself. Douglas had a nervous collapse, which inflicted further damage on a psyche already traumatized by the loss of sight in one eye and incapacitating headaches.

Instead of sending him back to a desk job in London, the RAF transferred Douglas to the most relentlessly bombarded base in the Mediterranean, the island of Malta. There he and two lusty local sponge fishermen were assigned to a submarine. Their job was to explore the seabed around Sicily and the toe of Italy, where the allies proposed to invade. Because Douglas was mildly claustrophobic, he did not enjoy being pinned to the Mediterranean floor by depth charges for days at a time. He felt like a turbot at the mercy of a trawler, he said, and, “oh, the smell—a mixture of BO, farts, and fear.” Back on the besieged island, life was even worse: the bombs rained down and rations were minimal. Douglas survived on black-market chickens and eggs, bought at vast expense from an archbishop.

As the war drew to an end, Douglas managed to have himself reassigned to the Monuments and Fine Arts branch of the Control Commission for Germany, the body that the Allies had set up to rescue and protect works of art and buildings from war damage, looting, vandalism, and the elements. His familiarity with European collectors, scholars, and dealers, as well as shippers, framers, and restorers, enabled Douglas to become one of the Commission’s most effective agents—as assiduous as Vautrin, according to a colleague, in his pursuit of Nazi looters. A principal target of Douglas’s sleuthing was the Swiss-born Herr Montag, one of Hitler’s art advisers, who had assembled a “private” collection of mostly looted works for the Führer. Douglas ran his quarry to earth in a mountain village near Innsbruck, where he had him arrested. However, Montag invoked a higher authority and got himself released. Douglas promptly had him rearrested; forty-eight hours later he was free again. The higher authority turned out to be Winston Churchill. Churchill had been taught to paint by “dear old Montag,” and refused to believe that he could have done anything reprehensible. “Thanks to the Prime Minister’s interference,” Douglas said, “we never managed to keep this criminal behind bars.”

Another of Douglas’s Nazi quarries, Walter Andreas Hofer, was someone he knew all about from the past. Hofer had once been Reber’s assistant, and had married Reber’s secretary’s sister. Later he had set up as a dealer and, after assiduously licking Goering’s boots, was appointed his art adviser. It was Hofer and his partners in crime, Karl Haberstock (Hitler’s art dealer) and Hans Wendland, who set up the nefarious “Swiss system” in partnership with the Swiss auctioneer Theodor Fischer of Lucerne, organizer of the Nazis’ infamous sale of “degenerate” art in 1939. The “Swiss system” enabled Hofer and Fischer and above all Goering to make huge profits. Swiss francs, generated by the sale of modern paintings looted from Jewish collections, financed the Reichsmarschall’s acquisition of ever more Cranachs and Dürers for his Valhalla-like hunting lodge. Hector Feliciano, whose excellent book on Nazi art thefts, The Lost Museum, makes good use of Douglas’s memoranda, has identified some twenty-eight major deals involving hundreds of paintings as the outcome of the “Swiss system.” There was another aspect to these transactions: outside Switzerland, Swiss francs were extremely scarce, and impressionist and post-impressionist paintings, which the Nazis despised and the Swiss loved, became an alternate form of hard currency. Picassos and Matisses were as negotiable as Swiss francs.

To Douglas’s embarrassment, Reber—desperate, as always, for money—turned out to have acted, briefly, as Hofer’s agent in Italy and thus to have had dealings with Goering. For some reason, Hofer turned against Reber and, with Goering’s help, had him investigated by the Gestapo, stripped of his German citizenship, and declared persona non grata by the Swiss authorities. As a result, Reber had to remain in Florence, frantically appeasing the Reichsmarschall with occasional offerings from what was left of his collection. He was not allowed back into Switzerland until 1947.

As an art sleuth, Douglas was especially proud of having commandeered the so-called Schenker Papers—records kept by the Paris branch of the principal German art shippers—which enabled him to track down virtually all the art that had been transported, legally or illegally, to Germany. These records were even more useful for recording payments, provenances, and destinations. Besides establishing that some of the most prestigious Parisian dealers in old masters and antique furniture presided like vultures over the liquidation of their former clients’ collections and their former colleagues’ stock, the Schenker Archive revealed the extent of the role played by German museums, notably the Folkwang Museum in Essen, in the looting of Jewish collections. Among much else, it also helped to establish the responsibility of Hitler’s so-called art experts—not least Eva Braun’s dim-witted girlfriend, Maria Dietrich—for shipping hundreds of paintings to the Führer’s museum at Linz. It was up to Douglas and his colleagues on the Fine Arts Commission to trace these pillaged works, and they did an extremely effective job.

Douglas was also very proud of uncovering the wartime activities of the powerful Jewish dealer Georges Wildenstein. He alleged that after the German invasion, Wildenstein had made a deal, as he often had before, with Hitler’s representative Haberstock, involving some major old masters; and that he then left for the United States, but not before Aryanizing his Paris gallery by putting it in the name of his head salesman, Roger Dequoy, so that it could continue to function under the Occupation. For the rest of the war Wildenstein helped to direct the affairs of Dequoy et Compagnie from the safety of New York, allegedly taking advantage of the situation created by the Nazi suppression of Jewish dealers and collectors. After the war Wildenstein and Dequoy were never nailed, and Wildenstein’s heirs consistently deny the allegations. However, according to Douglas some members of the French Fine Art Commission took the rumors so seriously that Georges Wildenstein never realized his dream of becoming a membre de l’Académie. In subsequent dealings with the Wildensteins, Douglas emerged as anything but a hero. In 1965 he wrote a blistering review of Georges Wildenstein’s supposedly definitive Gauguin catalogue raisonné, dismissing several works with a Wildenstein provenance as fakes or misattributions. The dealer sued him. After a great show of bravado, Douglas caved in and, to the utter amazement of interested observers, eventually agreed to an out-of-court settlement “on friendly terms.” The wily dealers knew just how to play on their opponent’s vanity, his enjoyment of being treated as a VIP. Why didn’t he revise their Gauguin catalogue, Wildenstein flatteringly suggested. Douglas was thrilled to accept, and devoted most of his last years to this project. “Georges Wildenstein is dead,” he would say rather lamely, “and they make such a fuss of me.” Although the revised catalogue was virtually finished by the time he died in 1984, there has been no talk of its publication. Scholars who had applauded Douglas’s attacks on the dealer were saddened that, after all the huffing and puffing, he should sell out and, worse, try to inveigle one or two of them into following his self-serving example.

His pursuit of Nazi loot and looters took Douglas frequently to Switzerland. Although the commission had no authority there, and Swiss law was—indeed, still is—much too favorable to people who buy works of art knowing full well they have been looted or stolen, Douglas did not hesitate to manipulate or embarrass the Nibelungen of Zürich into returning their ill-gotten gains. A major offender was the German-born Emil Bührle, a onetime student of art history who had married an armaments heiress and made an incalculable fortune during the war selling his Oerlikon cannons to the Wehrmacht as well as to the Allies. Although Bührle had benefited from Goering and Hofer’s “Swiss system” of barter, he was not disposed to make restitution to the rightful owners without a fight—a fight that this sinister war profiteer ultimately lost.

Under the terms of the German peace agreement, the Allies had the power to seize all German assets in Switzerland. Easier decreed than done. Douglas found the Swiss banks extremely uncooperative, and there were seldom any paper trails to follow, as there had been in Paris. Then again, many of the German assets in Switzerland did not belong to the Nazis but to the Nazis’ victims, a fact that did not necessarily exempt them from seizure. At one moment Paul Klee’s family was in danger of losing his very valuable estate to the Allies. When he died in Bern in 1940, this German-Swiss artist, whom the Nazis had stigmatized as entartet (decadent) was still in possession of a German passport. The Allies would thus have had the right to seize the vast accumulation of work he had left to his widow, Lily, and his son, Felix, a soldier in the German army who had ended up in a Russian prisoner-of-war camp.

In the course of his sleuthing visits to Switzerland, Douglas had renewed his friendship with Lily Klee and had dined with her in Bern the night before she died. He had also become very friendly with Rolf Bürgi, a powerful Bernese insurance man who had amassed the world’s largest and finest private collection of the artist’s work. Hundreds of Klees covered the walls of Schlössli Belp, the Bürgis’ snug little castle outside Bern, where Douglas liked to stay. Inevitably this new friendship involved a conflict of interest: Bürgi headed the group of Klee fanciers who had rescued the artist’s estate from Allied sequestration by arranging a “sale” that made it Swiss property. The more important works were deeded to a Klee Stiftung (foundation) at the Bern Museum. The rest became the property of a Gesellschaft (corporation) under the administration of Bürgi and his friends. They would have the right to settle prices and sell whatever they chose. Part of the proceeds were supposedly set aside for Felix Klee. Douglas did not question this arrangement. Bürgi had arranged for the Gesellschaft to sell him a number of very fine Klees very reasonably.

Back in London, in 1947, Douglas moved in with Basil, hung as much of the collection as the walls of Basil’s newly purchased Egerton Terrace house would hold, and embarked on a career of connoisseurship punctuated by controversy. The articles on nineteenth- and twentieth-century art that poured from his pen were superb—trenchant, innovative, eye-opening—especially when he was writing about the dead rather than the living, for instance, the art criticism of Delacroix or Baudelaire or Félix Fénéon. But if for some reason or another the subject raised his infinitely sensitive hackles, Douglas could be petty and spiteful. Alan Pryce-Jones, editor of the Times Literary Supplement, and an old friend, welcomed Douglas’s controversial contributions; they enlivened many an otherwise dullish issue. Unfortunately Douglas used the anonymity of the journal as cover from which to snipe on friend and foe alike, castigating them in interminable sottisiers for misplaced accents and typos rather than more heinous shortcomings. Douglas’s other organ of choice was the Burlington Magazine, whose pages were famous for giving rise to dusty but deadly art-historical disputes. Douglas bought a block of shares in the Burlington for their nuisance value. The shares did not give him much control over the contents, but they enabled him to make the life of the editor, Benedict Nicolson—son of Harold Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West, and supposedly a friend—an intermittent misery. “Somebody has to put some starch in that rag doll,” he said. “One laughs,” Douglas said of Ben on another fraught occasion, “but opens the jaws of the trap a little wider and snap—that head will soon be in the basket.”

Stuart Preston, New York Times art critic, ca. 1950

The resentment that his articles stirred up exacerbated Douglas’s Anglophobia. What had started as an aggressive pose became second nature and eventually got the better of him. One can hardly blame the English for retaliating. No sooner had he settled in with Basil than Douglas took to traveling monthly to Paris—“the only place for an intellectual to live,” he said. He claimed to feel more at home with the left-wing intelligentsia, which revolved around Picasso and Sartre, than he did with “those awful prissy Bloomsberries” back in London.

Douglas also decided to give New York a try. He had not been there for almost ten years and was anxious to spy out the art world and also to gather ammunition for an attack on the School of New York. Abstractionism, which Douglas saw as “cubism’s misbegotten child,” was having a resurgence in America. Abstraction died with Mondrian, he said; we cannot have it coming back to life. He also wanted to see how the Museum of Modern Art—and, more particularly, its director, his old friend and sometime enemy Alfred Barr—had transformed the way twentieth-century art was perceived: exhibited, collected, promoted, studied, and, not least, bought and sold. Douglas was in the market for additions to his collection, also for a lover (Basil had long since become emeritus). He renewed old contacts and made a whole raft of new ones, among them Bill Lieberman (then curator of drawings at MoMA), who became a close friend and acted as his cicerone, and Stuart Preston (then art critic on the New York Times), who would act as Douglas’s New York eyes and ears.

So stimulating did Douglas find New York that he was very tempted—particularly by one of his new friends—to settle there, collection and all. If he did not do so, it was probably because of ego. For all his Anglophobia, London enabled Douglas to behave like a very large toad in a relatively small pool. In New York that would have been impossible. The pool was much bigger and already full of toads, some of them every bit as formidable as himself. Another consideration: Douglas might have been inveigled into settling on the other side of the Atlantic, if he had not at this juncture met me.