GRAND TOUR

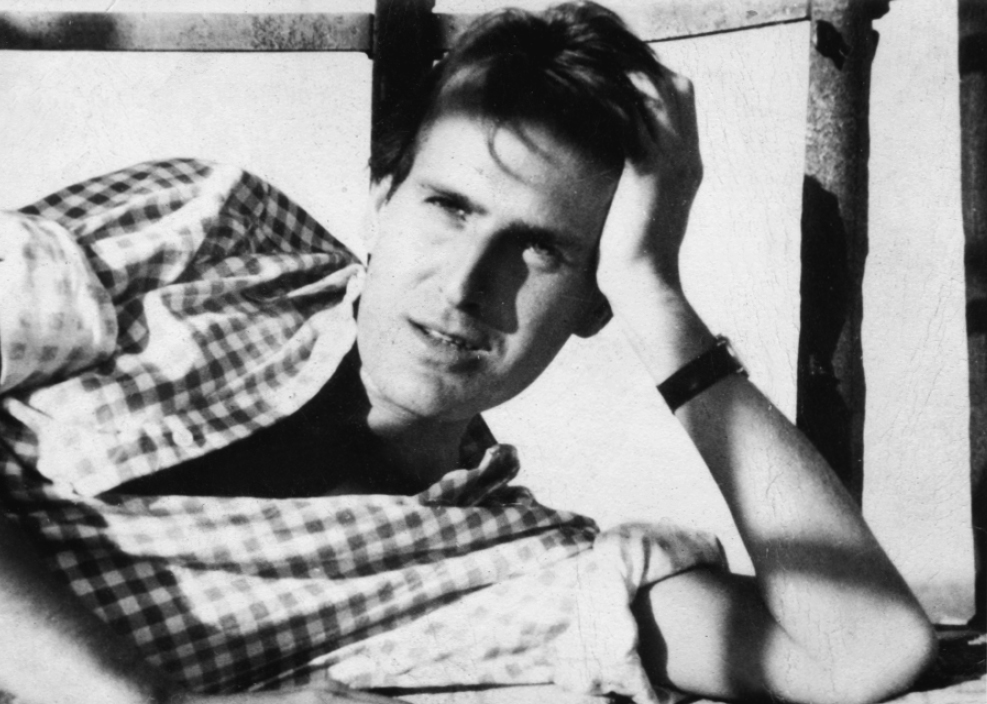

JR and T. C. (Cuthbert) Worsley on the ferry to Ischia, summer 1949

Our Grand Tour, which began in late June and lasted until early October, started grandly enough. Douglas put Basil’s old Rolls on the plane from Lympne to Le Touquet. To make the first leg of the journey more congenial, he had asked James Bailey to join us. It was not a good idea. Now that his Gustave Moreauish opera sets were having a success at Covent Garden, James, who was short and squat and hirsute, had started behaving in an inappropriately diva-like way, as if he were Tosca or Thaïs. His misfortune had been to grow up next door to the famously epicene Stephen Tennant, and rather too much of Stephen’s stardust and outrageousness had rubbed off on him. Once, when I was staying with the Baileys, James’s grim father had returned from buying some of Stephen’s land, holding the deed by a pair of tongs. “The closing took place in the feller’s bedroom,” Colonel Bailey fumed. “The document stinks of Chanel Number Five.” James made things worse by correcting him: “Nonsense, Papa, Arpège.”

Like Douglas, James had a horror of passing unperceived; and, sure enough, when we arrived at Le Touquet in the wasp-colored Rolls, with Douglas in horse-blanket checks, and James trailing a ten-foot-long angora scarf pinched from his mother, we were noticed. Tourists tittered, and even the douaniers raised their eyebrows. The attention—or was it the competition?—was too much for Douglas, and he saw to it that our paths diverged as soon as we got to Paris.

Having spent six months in Paris two years earlier, I thought I knew the city well enough, but Douglas revealed its splendors to me as never before. Every morning we would embark on a round of museums and monuments, galleries and private collections, or we would make sorties to Fontainebleau or Versailles, or to less obvious places like Ecouen or Champs. The big Gauguin retrospective was only one of many other exhibitions that Douglas was reviewing. The reopening of the gloriously installed Musée de Cluny enabled him once again to show off his knowledge of medieval art. Douglas shocked me by actually liking an oversized Utrillo retrospective and not liking a beautiful show in honor of Matisse’s eightieth birthday nearly enough. “Fiddle-faddle,” he said of this first appearance of Matisse’s marvelous papiers-découpés—“no comparison with cubist ones.” Douglas deplored my ignorance of the French classics and would take me to the Comédie Française, or the Opéra, or whatever was of interest at the theater. With the excuse of food shortages back home, we went in for a lot of serious eating and drinking.

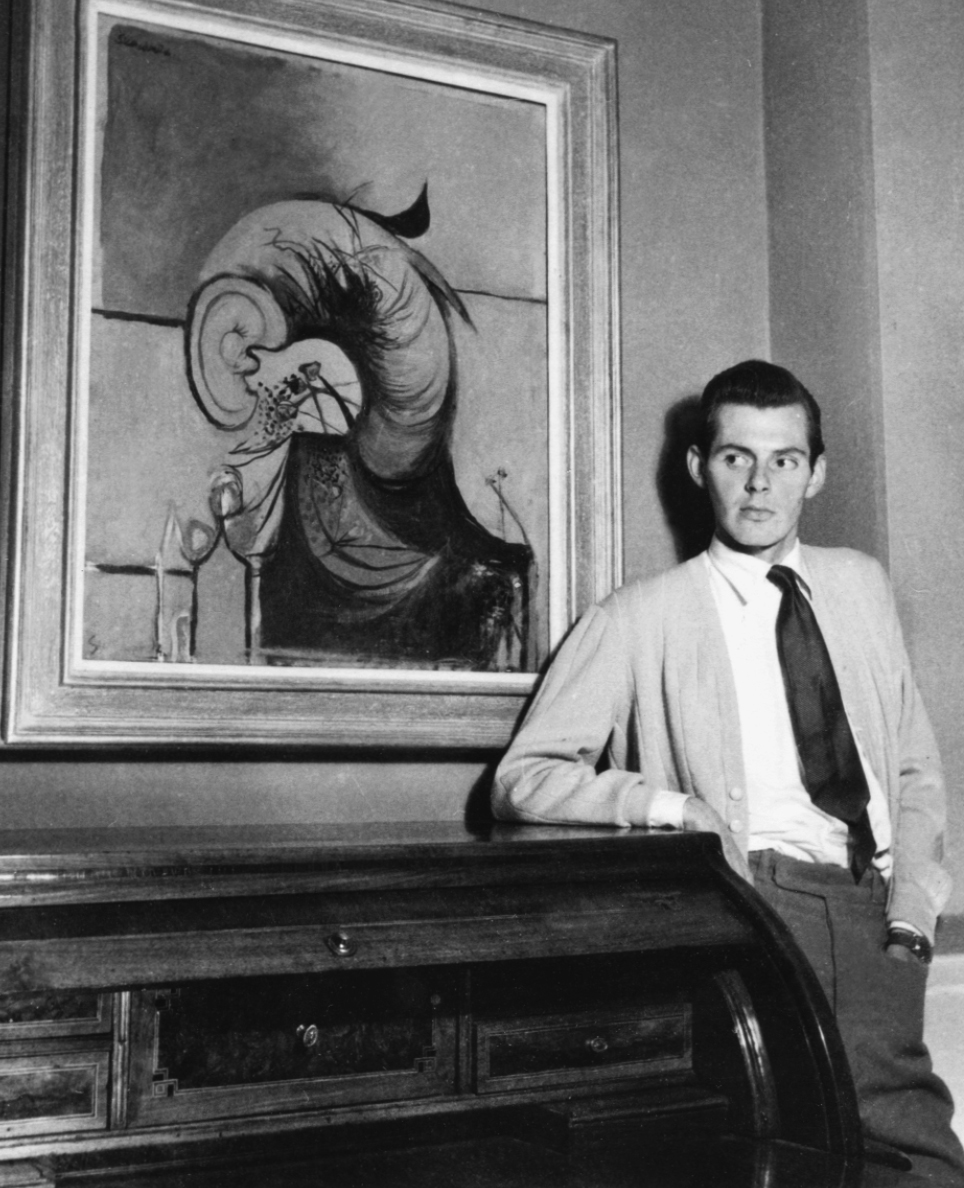

James Bailey, theater designer, 1946

Douglas took me to visit such celebrated friends as Léger and, most memorably, Picasso. As early as our second meeting, Douglas had tried to impress me by calling Picasso in Paris as if for a casual chat. The artist did not come to the telephone, nor did he do so on several subsequent occasions. Far from being impressed by Douglas’s intimacy with the great man, I felt acutely sorry for him. Why expose himself to these unnecessary rebuffs? A few weeks later, when I accompanied him to Picasso’s rue des Grands Augustins studio, we were received warmly enough, but no more so than the other ten or so supplicants—collectors, publishers, photographers, dealers, journalists, fans, and friends—who had arrived, bearing gifts in the hope of a favorable response to their requests. What surprised me was Picasso’s smallness and delicacy, also the unassuming courtesy—those radiant smiles—with which he greeted people, who seldom had a language or anything else in common with him and seemed only to want to waste his time. Each of the supplicants needed something from the artist: a charitable donation, a book jacket, a signature on an unsigned work. Simpler requests were satisfied there and then. More complicated ones were listened to and seemingly acceded to. However, as I later discovered, Picasso had as many ways of saying yes while meaning no as a Japanese: “I’ll do my very best” or “I’ll be in touch” usually implied the opposite. Even when he was interested in a specific project, he would prevaricate for months before getting down to a promised drawing or collaborating on a promised exhibition. The only gratification that Picasso can have derived from these audiences was a papal one: the reassurance that the faithful were still faithful. This need for reassurance would become ever more pressing in the 1950s, when the avant-garde would start melting away in the direction of abstract expressionism or—Picasso’s pet hate—neo-Dadaism. “All they have done is change the wrapping-paper,” he said.

Above all, I was fascinated by the way Picasso used his huge eyes as a hypnotist might, raking the room for possible subjects. At one moment he turned his eyes on me and held my gaze for long enough to induce a responsive quiver. He was good at spotting susceptible people. When he went on to do the same thing to another new face, I felt slightly betrayed. After getting to know Picasso better, I would be amused to watch him fix his voracious stare on one unsuspecting person after another—regardless of age or sex. The mirada fuerte, the “strong gaze”—so highly valued by Andalusians, who believe that the eye is akin to a sexual organ and that rape can be ocular—never failed to work its magic.

The unaccustomed tensions of life with someone as hyper as Douglas were already taking a psychic toll. In Paris I developed a mysterious fever. Douglas claimed to have a doctor friend who could cure psychosomatic ailments, Jacques Lacan. This man had yet to become a celebrated intellectual guru. If Douglas had faith in his powers, it was because Picasso had entrusted Dora Maar to his care after her crack-up five years earlier. When this dandified doctor materialized in our room in the Hôtel des Saints-Pères, my temperature shot up even higher. “Enlevez votre pyjama,” Lacan said, and peered at my sweating torso with distaste. He took a large Lanvin handkerchief from his breast pocket, laid it over my chest—as doctors used to do before the invention of the stethoscope—and listened from a safe distance, nodding sagaciously as he did so. This diagnostic charade ended with Lacan tearing a page from his Hermès diary and, after a pensive pause, writing down the address of another doctor. I subsequently saw Lacan a few times, but was never able to take this brilliant man as seriously as intellectual fashion dictated. The contrivance was such that he seemed like an actor playing himself.

Basil, who had been attending a parliamentary congress in Paris, joined us for the first leg of the trip. I was still feverish—pleased to have a doctor along. In midmorning we broke our journey for a couple of bottles of Pouilly-Fumé on a terrace overlooking the Loire. And then Douglas sped on to Moulins to look at the great triptych in the cathedral and treat us to a four-course lunch that would have disqualified anyone else from driving. Afterwards he wrapped me up in rugs in the jump seat, where, windblown and sweat-drenched, I slept until we arrived at Aix-en-Provence. The music festival was a new attraction, and Douglas had obtained seats, the following evening, for Don Giovanni in the courtyard of the archbishop’s palace. I took the precaution of staying in bed. Unfortunately, Segovia, most revered of classical guitarists, had the room above mine, and was practicing for a concert later in the week. The sequence of three nasal notes played over and over again for hours at a time—ping, pang, pung; pung, pang, ping—was like water torture. Sleeping pills put me out of my misery, but the aftereffects kept me dozing through much of Don Giovanni. All I remember is the Don’s missing fingers—frostbite, I was told.

While we were at Aix, Douglas insisted that we call on old friends who lived there, Georges Duthuit and his wife, Marguerite, Matisse’s formidable daughter. Marguerite seemed far from pleased to see Douglas, and arranged to receive us on the sidewalk outside their house. Later I discovered why. When war had broken out in 1939, the Duthuits were staying with Douglas in London. As foreign checks were no longer negotiable, they had run out of money, and had asked Douglas to lend them twenty pounds for their journey home. Marguerite, who was exceedingly scrupulous, had left one of her father’s drawings, a beautiful 1916 Vase with Ivy, with him as collateral. After the war, she had tried to repay the money and recover the drawing, but Douglas was not prepared to relinquish it. He insisted that she had sold it to him. Marguerite was too fastidious to pursue the matter further, but it understandably rankled, which is probably why her majestic, lion-headed husband insisted on taking us off to a café and plying us with questions about the friends he had made in London before the war.

From Aix we went on to the in those days privately owned Mediterranean island of Porquerolles. Basil had been asked by officials at the Quai d’Orsay whether he would like them to arrange holiday accommodations for him. Tell them to get us lodgings on Porquerolles, Douglas said. The island (just across from Hyères) belonged to an elderly, partly French, partly English woman called Madame Fournier; and as Douglas suspected, her private house, which abutted the sea, would be far and away the best place to stay. Sure enough, at the Quai d’Orsay’s prodding, Madame Fournier put the three of us up at her villa, and we spent our days relaxing on her virtually deserted beaches and eating langoustes at the one and only hotel. “You are not at all my idea of official guests,” she said. Except for a boat trip to the neighboring Ile du Levant—a disappointing nudist colony that did not countenance anything more radical in public than toplessness—we stayed on Porquerolles for almost two weeks. Douglas worked intensively on his Léger book. I lay in the sun and beachcombed and recovered from my fever.

After leaving Porquerolles, we toured around the Riviera—Saint-Tropez, Antibes, Cap Ferrat, Monte Carlo—before driving to Geneva for meetings with Douglas’s Swiss publisher. Then on to a succession of great exhibitions: medieval art at Bern; Rembrandt at Schaffhausen; Matisse at Lucerne; Bellini at Venice; and a week’s total immersion in the Renaissance at Siena and Florence. Then back to Venice via Arezzo, Urbino, Ravenna, Ferrara, and Mantua. I was enormously grateful for Douglas’s crash course in Western art, but more than ready to join Cuthbert for a few days in Naples—the starting point for our visit to Auden, who had a house on the island of Ischia, Capri’s less spectacular neighbor.

I had another reason for going to Naples. I wanted to see an old friend from Oxford, the great zoologist J. Z. Young, who spent the summers with his adorable, down-to-earth girlfriend, Raye, in the research section of the city’s famous aquarium, experimenting on octopi. John allowed Cuthbert and me to watch him at work. The purpose of the experiments was to isolate the area of memory in the brain. John would train his octopi to react to certain electrical stimuli and then remove a slice from this or that part of their brain, to see whether or not they remembered the shock. Thanks to John’s skill at making scientific procedures comprehensible as well as totally absorbing—a skill that made for the success of his books—Cuthbert and I became so enthralled that we ended up spending our time in the aquarium instead of visiting the great Neapolitan churches and monuments that Douglas had instructed me on no account to miss. John showed us how the octopi, who were kept in separate compartments, tried desperately to find an aperture through which to insinuate their tiny sex-organ tentacles into the neighboring pens. He also showed us how octopi change color according to whether they feel fear, lust, or aggression. Had the aquarium replaced the so-called mermaid that Curzio Malaparte describes in his book The Skin being served up with a garnish of mayonnaise and bits of coral as the centerpiece at a dinner given by the American general in charge of starving Naples? “Must have been a manatee,” John said dismissively. He and Raye were also leaving for Ischia. We arranged to meet.

JR at Aigues-Mortes, 1950

A photograph taken on the ferry from Naples to Ischia shows Cuthbert and me looking carefree, although both of us must have realized that the fireworks of Ferragosto—Italy’s Fourth of July—would probably mark the end of our attachment. Wystan’s house at Forio had been partly destroyed in an earthquake and never entirely rebuilt. Some of the rooms had been left open to the sky. In place of ceilings or awnings, Chester Kallman, Wystan’s funny, zaftig boyfriend, had run wires from one wall to another and trained morning glories to grow along them. The effect was charming—heaven knows what happened when it rained. After a month of grand hotels, three-star restaurants, and constant exposure to the West’s greatest art and architecture, the sun-baked sparseness of Forio, with its lack of modern amenities, not to speak of ancient monuments, came as a relief. For someone who had overdosed on great art, Ischia provided a wonderful corrective. It had none of Capri’s transcendent theatricality. It was unspoiled and to that extent impoverished, but not distressingly so. People seemed content with their lot. Chester told a friend that when he first arrived on the island, “he was taken by a local boy into the family vineyard. Once there, the boy made it abundantly clear that for five hundred lire (less than a dollar even then), Chester could have him and all the grapes he could eat.” Cigarettes were sold individually; lighting in most houses took the form of a single, dangling low-wattage bulb; the local cuisine was limited to pasta and pizza. Fine with me: I loved pasta, and pizza was still such a novelty in England that I had never tasted it before.

After a month of Douglas’s disconcerting oscillations between bossy affection and didactic showing off, Wystan’s steadiness of mind and character came as a relief. It was also reassuring to fall into the quasi-monastic schedule that he managed to impose on his household. Work—exhaustive reading or writing—was the order of the day, but everything stopped at appointed times for tea or martinis or visits to the café. Getting drunk or having sex was fine, but there was a time and a place for it and, as I was to discover, certain unspoken rules. I can still see Wystan, accompanied by his snappish mutt, Moses, on his dusty way to or from the village store, his bare feet as callused as a fakir’s and his wonderful face crinkled like a shar-pei’s (“We will have to smooth him out to see who it is,” Stravinsky had said). I can still hear the jokes—about the village idiot, whom he had nicknamed “Harvard,” or about Wagner’s confession late in life, “I adore Rossini, but don’t tell the Wagnerians.” I remember being struck by the wisdom of Wystan’s comments, and the way they made one perceive familiar things in sharper, deeper relief.

Also staying in the house was a young writer called Jimmy Schuyler, whom Chester had invited along with his demonic friend Bill Aalto (a former guerrilla warfare expert), to look after the Forio house the previous winter while he and Wystan were back in New York. In the spring, Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams had come to stay, each with a lover in tow; and there had been a lot of disruptive drinking and shrieking. After they left, Aalto had tried to kill Jimmy with a carving knife, and then fled back to New York. Jimmy had stayed on, typing out Wystan’s manuscripts. Though not yet the delectable poet he later became, Jimmy had one of those mesmerizing sensibilities peculiar to schizophrenics. With his short haircut, tight blue jeans, and white T-shirt, he epitomized the fresh American sailor-boy look that would soon become mandatory for young men everywhere. I was dazzled. Chester took us down to the beach to swim and then to have drinks with a gaggle of alcoholic remittance men. Their campy giggles dismayed Cuthbert. He hurried back to be with Wystan, who was good at dealing with psychotic friends. I stayed because Jimmy stayed. I had no thought for anyone else.

Chester Kallman on the boat to Ischia

The second or third night, Jimmy and I waited until the household was asleep and lugged a mattress out onto the moonlit terrace, where we made frenzied love under a fig tree. For Jimmy this can hardly have been a novelty; for me this wild night turned out to be a Dionysian rite de passage. A rustle from within the house indicated that someone was watching. Jimmy pointed into the darkness. Wystan’s head could just be discerned peering over the wall of one of the ceilingless rooms. He must be standing on a box, Jimmy whispered. “Don’t stop.” Moonlight bathed us. Wystan went on watching, maybe Cuthbert, too; we went on with whatever we were doing.

At breakfast I was still too euphoric to look contrite. Cuthbert was wearing sunglasses. Wystan seemed cross and schoolmasterish. Dear Chester, so often in trouble himself, gave me a conspiratorial leer. Jimmy was nowhere to be seen. Without anything being said, I was made to feel that although a guest in an exceedingly permissive household—both Wystan and Chester had Forian lovers on the side—I had thoughtlessly transgressed. I had hurt the feelings of the vulnerable friend who had brought me; I had reawakened Jimmy’s demons; and I had offended against Wystan’s exacting sense of the right thing. Better go and pack, Cuthbert murmured. After tight-lipped farewells, Cuthbert and I made our way back to the island’s principal town, Ischia Porto.

W. H. Auden (center) with Irving Weiss at Maria’s Caffè, Ischia

When I next saw Wystan and Chester, two years later, Chester was in disgrace. It was in Venice in 1951. They were there for the opening of The Rake’s Progress, the opera they had written and Stravinsky composed; Douglas and I were staying with Peggy Guggenheim. Chester had picked up an Italian sailor who pretended to be so smitten that he had to be given “something of value” as guarantee of a further tryst. What did Chester hand over but his precious Parker pen—a Christmas present from Wystan. When Wystan found out, he went straight to the police and insisted that they pressure the naval authorities into pressuring the sailor to return the talismanic pen. The intervention worked.

Ischia Porto turned out to be crowded with Neapolitan holiday-makers celebrating Ferragosto. After several drinks with John Young and Raye, who had come over for the occasion, I too felt like celebrating. In a fit of alcoholic rapture, I ripped off my shirt and shoes and, to the noise of firecrackers, made a wild dive into what I took to be the harbor. The water turned out to be eighteen inches deep; a bit of rusty metal on the bottom gashed my head open. Retribution! Cuthbert took me to the hospital and fed me grappa by way of an anesthetic as the banana-fingered doctor darned the skin on my skull. The pain was intense, but it allayed my guilt, also some of Cuthbert’s despair. For the rest of our stay in Ischia, he was less tearful.

Chester Kallman and James Schuyler Ischia, 1948–49

Through Wystan we had met the duo pianists Bobby Fizdale and Arthur Gold, who had rented a house on the island with Edwin Denby, most perceptive of ballet critics. They were a vast improvement on Chester’s drinking companions. Denby would become Jimmy Schuyler’s next lover, only to be replaced, a year or two later, by Arthur Gold. And then, in 1951, Jimmy went temporarily out of his mind. After telling friends that the Virgin Mary had warned him that Judgment Day was nigh, he was confined to a mental hospital. There, thanks to Frank O’Hara’s encouragement, Jimmy developed into a poet of great visual sensibility. As he noted in his diary, “I’m a poet / and I know it.” He also became exceedingly fat. I never met Jimmy again. After I moved to New York, he and I must often have been at the same party or concert or bar, but Jimmy told a mutual friend that he wanted to be remembered as a beauty, and that indeed is how I remember him.

My next stop was the Waldhaus in Davos, where Geoffrey Bennison told me the good news—Aureomycin had saved his life—and the bad news: his savings were running out and he hated the sanatorium. During World War II, the Swiss had allowed the Nazis to have tubercular soldiers and sailors treated at the Waldhaus; and to believe Geoffrey, there was still a whiff of the Wehrmacht—nurses like Gauleiters. The patients were a different matter. Geoffrey saw their little dramas through the eyes of Vicki Baum (author of Grand Hotel) rather than Thomas Mann. Although almost recovered, he still had his meals in bed. I took mine downstairs in the dining room so that I could fill him in on what passed for sanatorium gossip: “Nice Mr. X is no longer sharing a table with awful Fraulein Y”—that sort of thing. At lunch one day there was something more exciting to report. An elegant Italian couple had brought their handsome young son for treatment. The family could not hide their grief, any more than the other patients in the dining room could hide their curiosity. Each of the women patients got a glint in her eye. So did Geoffrey, when I told him what had happened. That evening he insisted on coming down to dinner to meet the new arrival. Geoffrey’s warmth was as seductive as his wit, and in no time they became the closest of friends. Enrico, the Italian was called, and he turned out to share Geoffrey’s passion for film and theater. Geoffrey did some marvelous drawings of him, and sanatorium life became much more tolerable for the two of them. A decade or so later, they would both make names for themselves: Geoffrey as London’s most imaginative antiquaire and decorator, and Enrico as a key collaborator in Luchino Visconti’s films.

Geoffrey Bennison, London, 1946

While I was at the Waldhaus, I had a mild attack of sinusitis and asked one of the doctors for an antihistamine. Only after giving you a full checkup, he said. I told him I had just had one, but that made no difference. Geoffrey warned me that the checkup would involve X rays, which were bound to be positive. “They’re Swiss,” he said. “All they’re interested in is your lolly, so they’ve got the X rays rigged. You’ll be here for life. The only way you’ll escape is feet first or by going broke like me.” Just as Geoffrey said, the head charlatan summoned me to his office, pulled a long Swiss face, and told me I had a patch on my lung. But not to worry, if I checked into the Waldhaus I would be cured in a year or two. They had a nice room with a balcony next to Geoffrey’s, and they were ready to start treatment at once. I called Douglas, who was waiting for me to join him in Venice. I’ll drive up tomorrow and rescue you, he said. This was a mission after Douglas’s own heart. The following afternoon he arrived in fierce fighting form and treated everyone to a torrent of Schwizerdütsch invective. When the head doctor insisted that I was tubercular and must remain in the sanatorium, Douglas said he wouldn’t dream of leaving anyone in the care of quacks and swindlers. And off we drove, Douglas berating the Swiss for turning a blind eye to Nazi war crimes whenever there was a profit to be made; and yet in his paradoxical way he really rather loved them. A few weeks later I had myself X-rayed again—just in case. There was no sign of lung disease.

The Grand Tour continued until mid-October. I had the feeling that Douglas did not want to return to London, where he would no longer have me to himself. After Davos, we moved on to Zürich to see his friend Gustav Zumsteg, proprietor of that excellent restaurant the Kronenhalle, where Lenin and James Joyce and the Dadaists had been patrons thirty years before. Gustav was very proud of the modern masterpieces—Braques, Picassos, Matisses, Mirós—that hung on the restaurant’s walls. He was also very proud of the silk he manufactured and sold to Paris couturiers, notably Balenciaga, whom he had come to revere as a latter-day saint of fashion. This irritated Douglas: “I wish Gustav would stop crossing himself every time he mentions the name of that lugubrious Spanish dressmaker.”

From Zürich we set off on an intensive tour of Swiss private collections, which Douglas knew by heart: Oskar Reinhardt’s private museum at Winterthur, and Baron Thyssen’s La Favorita at Lugano, where we were horrified to find the baron’s restorer, a former English guardsman, scrubbing and polishing the old masters as if they were buttons or boots. He was about to start on the van Eycks. Douglas implored him not to touch them. Alas, he did. We also went to collections that were more difficult of access. Best of all was the handsome house on a hill outside Basel belonging to the Swiss conductor Paul Sacher and his wife, a Hoffmann-LaRoche heiress. Their house was a shrine to modernism. Sacher owned the world’s finest collection of modern musical manuscripts; his wife, who was a great friend of Braque’s, had put together a wonderfully discriminating collection of contemporary masterpieces. The scariest collection we visited was housed in a sinister bürgerlich mansion on the outskirts of Zürich belonging to Emil Bührle, the armaments manufacturer whom Douglas had nailed as a major purchaser of paintings looted from Jews. It was impossible to disassociate the van Goghs and Cézannes on his walls from the carnage that had gone to pay for them. Far more attractive was the vast and varied collection belonging to an industrialist called Joseph Müller, who owned a nuts-and-bolts factory in Solothurn and used to ride to work on a bicycle. Besides great Cézannes, Renoirs, and Kandinskys, Müller’s scruffy mill house was jam-packed with treasures: cubist paintings in a room furnished with an old treadle sewing machine, racks of Rouaults in a higgledy-piggledy attic, and African masks and blood-stained tribal furniture in a bedroom hung with some of the Swiss artist Ferdinand Hodler’s scenes of nude figures copulating by the side of an Alpine lake.

The next year we made a trip to Scandinavia, and in Stockholm spent some time with Douglas’s old friend Rolf de Maré, the legendary Maecenas whose adventurous Ballets Suédois had given Diaghilev’s company a run for its money in the 1920s. Meanwhile, I developed a passion for Gustavian neoclassicism, above all for Gustavus III’s miraculously beautiful pavilion at Haga, and the work of Gustav Piló, his court painter. Piló’s vast, diaphanous masterpiece of the king’s coronation and his portraits in tones of copper sulfate, aquamarine, and ice still strike me as being among the eighteenth century’s best-kept secrets.

In Copenhagen we discovered yet more Pilós in one of the royal palaces, not to mention an amazing array of Gauguins and Matisses in various Danish museums. Our only disappointment was a visit to the elegant country house of Baroness Blixen, who wrote under the name of Isak Dinesen. Her early autobiographical book, Out of Africa (later made into a horribly hokey film), and Gothic Tales had a sizable following, but she had yet to transform herself into a sacred monster on the international circuit. I did not take to Blixen. A friend of mine, who had been one of the first British officers into Denmark after the German occupation, told me that when he drove up in his jeep to deliver a care package from her publisher, the baroness had run off to hide in the raspberry canes at the bottom of her garden. She assumed he had come to arrest her for consorting with the Germans. I was put off by the affectation and contrivance of Blixen’s appearance. She asked me to come up with suitable names for the characters in a story she was writing about nineteenth-century London, but I did not think enough of her stories to bother. Years later in New York, I was amazed when Mary McCarthy and others who should have known better touted this self-invented Germanophile pasticheur as a possible Nobel Prize winner.

The shock of twenty-four hours in what Douglas described as hellhole London was such that he insisted that we retire to the peace and quiet of the Bear hotel at Woodstock outside Oxford. The pretext was work—after three months’ absence, both of us had a lot to do—but the real reason for this rustic interlude was Douglas’s desire to prolong my éducation sentimentale. When we were not working or going for long, damp walks in the park at Blenheim, we would visit Oxford friends or inveigle the owners of stately homes to let us in. This suited me fine: I was writing a lengthy, would-be authoritative review of Margaret Jourdain’s book on William Kent for the Times Literary Supplement. Rousham—one of Kent’s finest houses and gardens—was only a few miles away, and the owner provided me with a lot of unpublished information. Despite efforts to the contrary, my Kent article turned out to be all too redolent of Douglas’s influence: querulous, academic, and unnecessarily nitpicking. Cuthbert, who was forgiving enough to go on seeing me, was appalled at the snooty tone and implored me not to sacrifice liveliness to art-historical bickering.

Looking back, I can see that Douglas wanted me to turn into one of those tasteful young dilettantes who explore the byways of the decorative arts. He had already picked out the subject of my first book: John Opie, a late-eighteenth-century painter celebrated for his chiaroscuro portraits and quirkish genre scenes executed with an overloaded, bituminous brush. This was preordained, Douglas said, because I had recently discovered The Fortune-Teller, Opie’s lost masterpiece, in a junk sale. “The lost masterpiece” would soon be lost again—this time for good. I had left it with my disaster-prone family; there was a fire, and nobody bothered to rescue it. Fortunately, no publisher was interested in Opie, but that did not stop me from wasting too much time writing boringly about things that bored me. Douglas did not want anyone—least of all his lover—poaching on what he regarded as his preserves.

While we were at Woodstock, Douglas persuaded Basil to let me move into Egerton Terrace. At last I could get away from my family. Under the terms of my father’s will, my mother had the right to move house as often as she wanted, so long as I was the nominal owner of the property. While I was out of the country, my younger brother had persuaded her to sell our house off Thurloe Square and move to a flat where there was no room for me. Basil’s generous provision of his one and only guest room and a study on the ground floor was a godsend. Offers to contribute to the costs of the household were brushed aside. Thanks to Basil’s goodheartedness, the arrangement worked well. Far from being resentful or jealous, “Our Lord” was most welcoming—anything to keep Douglas happy. It somehow never occurred to me that I might have forfeited my freedom.