PAINTERS AND PAINTINGS

Georges Braque, 1955

Douglas had been reluctant to let me write about his four favorite artists, but I went ahead and adopted Braque as my special concern. I had always loved his work and soon came to love the man, who was the antithesis of Picasso—cool, meditative, at peace. He not only looked like a saint, he behaved like one: a saint of painting. Unlike Picasso, who desperately needed admirers to feed his voracious ego, Braque was self-sufficient, but he enjoyed discussing his work and his vision of art, which he would do with a wonderful metaphysical clarity. Over the next few years I would devote a couple of books and several articles, including a lengthy analysis of his great Atelier series, to his work. There was an advantage to doing this at Castille; my study was lined with some of Braque’s finest paintings and they permeated the room.

At first Braque came across as daunting and withdrawn. However, once he realized that I understood his “difficult” late work, he opened up. So did his wife, Marcelle—small, fat, wise, and funny, not least about Picasso, whom she enjoyed putting down with a mixture of exasperation and affection. I remember her reminiscing about the time (1912–13) she and Braque and Picasso and Eva had settled at Sorgues, near Avignon. The four of them would take long walks together in the garrigue. If the mistral was blowing, they would assume Indian file: first big, brawny Braque, then plump Marcelle, then frail Eva, and finally little Picasso, cowering in their shelter. Picasso was less of a hero outside the studio than inside, she said. I suspect Marcelle never entirely forgave him for referring to her husband as his “ex-wife.” Apropos this famous old slight, I always wanted to, but never dared, tell them a story (circa 1938) told to me by Dora Maar. Hearing that Braque had been hospitalized, Picasso rushed off to see him. He returned home in a rage. The nurse had refused to let him into his room because Madame Braque was in there with him. “Don’t they realize that I am Madame Braque?” Typical of Picasso to stand his original joke on its head. Au fond, his most abiding male friendship had always been with Braque, Dora said. It was Braque who distanced himself, in part for ideological reasons. While he had drifted to the right—he sympathized with the fascistic Croix-de-feu—Picasso had been drawn more and more to the left.

DC and JR with Braque in his studio at Varengeville, ca. 1955

Whenever I saw him, Picasso would ask for news of Braque. Braque never asked for news of Picasso, and on the very few occasions I saw them together, he would sooner or later do or say something to needle his old friend. One day, when we were all together at La Californie, Picasso asked us to come up to the studio and look at his recent work. Only Braque said no: he had arranged to take a ride in the photographer Dave Duncan’s hot new Gullwing Mercedes. Picasso was furious. He told me that when he had offered his old friend a studio at La Californie so that they could work together again, Braque had said he preferred to stay at Saint-Paul-de-Vence with his dealer, Aimé Maeght, a man Picasso loathed. Another slight: Picasso had sent Braque one of his ceramics—a suitably Braque-like dinner plate decorated with fish bones and a slice of lemon—and never received any acknowledgment; would I find out what had happened? Braque had indeed received it, but thought it was une blague—a joke. “Picasso used to be a great painter,” Braque liked to say. “Now he is merely a genius.”

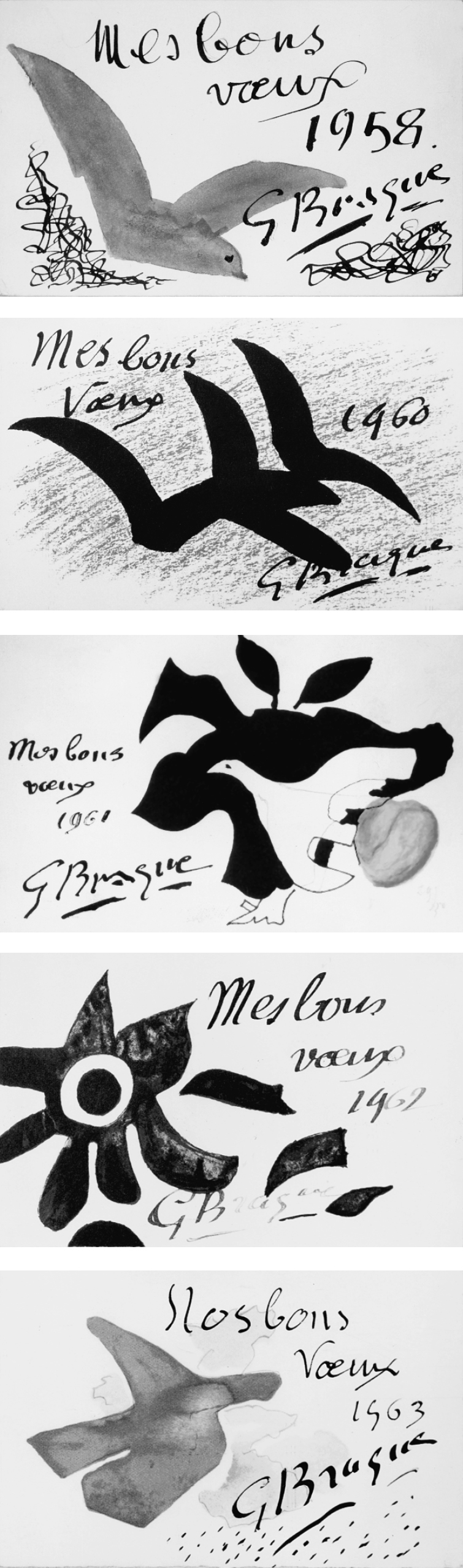

New Year’s cards, pen and ink and watercolor, done by Braque for his friends

By the mid-fifties, Braque had turned into something of a hermit, much as Picasso would ten years later. His studio had become the center of his universe; it was also the primary subject of his work. If the light was curiously palpable—what Braque called “tactile”—it was because he kept his studio skylight veiled with thinnish, whitish material, which filtered and seemingly liquefied the light. In this penumbra the artist would sit as hieratically as Christ Pantocrator in a Byzantine mosaic, his great big Ancient Mariner’s eyes devouring the paintings set out in front of him. The monastic hush would be broken only when he got up, wheezily, to make a slight adjustment to one of the many canvases arrayed in front of him. On my first visit to the artist’s studio, I felt I had arrived at the very heart of painting. I never quite lost that feeling.

Braque accepted visitors from the outside world as a hermit might, without ceremony or curiosity. Unlike Picasso, he did not mind having people in the studio when he was painting. One afternoon in 1956, he let me stick around for a couple of hours while he worked on A Tir d’Aile (In Full Flight), his eerie painting of a sleek black bird crashing into a cloud as if it were a Stealth B-2 bomber breaking the sound barrier. For weeks, Braque told me, he had been adding layer after layer of paint to the grayish-bluish sky to give it an infinite tactile density. As a result, it was so heavy he could no longer lift the canvas on or off the easel. Compared to the weightiness of the sky, the bird and cloud have as much substance as shadows. Braque had been reading about black holes: hence the concept of the cloud as a black void with a gravitational force that nothing can escape. It has been suggested that this blackness might also signify death. And indeed, by the late 1950s Braque was in very fragile health. Mortality held fewer fears for him that it did for Picasso; if anything, it challenged him, as in this painting, to bring le néant within his grasp, and to that extent within ours.

Georges Braque, Bird Returning to Its Nest, oil, ink, pencil, and cut paper on cardboard, 1955; given by the artist to JR

Apropos another bird painting, Braque talked to me about his visits to the Camargue, where our mutual friend the ornithologist Lukas Hoffmann (heir to the Hoffmann-LaRoche fortune and son of that perceptive modernist collector Maja Sacher) had established a vast bird reserve, La Tour du Valat. Douglas and I used to drive around in a jeep with Hoffmann, who would point out that the distant streak of quivering coral color ringing the vast Vaccarès lagoon was in fact flock after flock of flamingos. I also used to go riding there with our bull-breeder friend Jean Lafont, helping him round up the wild bulls that graze the salt marshes. Like the bulls, the wild but gentle horses we rode were native to the marshes; they are still never shod and their mouths are too soft to pull on, their flanks too soft for spurs—just a flick of a rein against their beautiful white manes, and they respond. Anything stronger and they throw you in the mud. Braque told me how the apparition of a heron flying low above the marshes had inspired his large 1955 Bird Returning to Its Nest, of all the late paintings the one that meant the most to him. Maybe because I shared his feelings for the Camargue, Braque gave me an oil study for this haunting work. I remember him saying how, on still, gray days, the sky seemed to reflect the lagoons rather than the other way round, and the birds seemed to swim through the air. Nor could he forget the swarm of mosquitoes.

I stayed close to Braque because I wanted to keep track of the nine large Ateliers he worked on from 1949 to 1956. Their subject is nothing less than painting itself, as practiced by the artist in the seclusion of his studio. They constitute a microcosm of Braque’s private universe. There is no trace of a human presence, except insofar as Braque’s Zenlike spirituality suffuses them. Until I came along, nobody had studied them in depth. To understand these Ateliers, it is necessary to evoke the carefully contrived clutter of Braque’s studio: a space that was divided in half by a cream-colored curtain, in front of which numerous recent and not so recent works were arrayed on easels, tables, and rickety stands. Some of the paintings were barely started but already signed; some looked finished but lacked a signature; others dated back five, ten, even twenty years—“suspended in time,” the artist said. “I ‘read’ my way into them, like a fortune-teller reading tea leaves.” Sketchbooks (“cookbooks,” Braque called them) lay open on homemade lecterns. Pedestals contrived out of logs and sticks picked up on walks were piled high with materials: palettes galore, massive bowls bristling with brushes, and containers of all kinds of paint, some of it ground by the artist and mixed with sand, cinders, grit, even coffee, to vary the texture. On the floor were pots of philodendrons, which Braque liked because the shape of their leaves “rhymed” with the shape of his palette, as well as simplistic sculptures carved from chalk—fishes, horses, birds—all of which make fragmentary appearances in the Ateliers. Elsewhere a shelf was set with tribal sculpture, musical instruments, and the large white jug that dominates Atelier I.

The presence of an enormous bird in these paintings is less enigmatic than it might seem. It does not represent a real, live bird but a “painted” one, an image that has detached itself from its canvas ground. When Braque embarked on the series, there was a large painting of a bird in flight (later destroyed) in the studio, and it is this image that appears in different guises in all but one or two of these paintings. Braque pooh-poohed suggestions that the bird might have symbolic significance: an ectoplasmic materialization, a sacred Egyptian ibis, a Picasso-esque dove of peace (the journalist who made this suggestion was asked to leave), or, silliest of all, that a real bird might have flown in through the window. These birds materialized on their own, Braque insisted. “I never thought them up; they were born on the canvas.” In a long interview I published in the London Observer, Braque went on to explain: “I have made a great discovery, I no longer believe in anything. Objects don’t exist for me except insofar as a rapport exists between them or between them and myself. When one attains this harmony, one reaches a sort of intellectual nonexistence—what I can only describe as a sense of peace—which makes everything possible and right. Life then becomes a perpetual revelation. Ça, c’est de la vraie poésie!”

Georges Braque’s Atelier VIII, oil on canvas, 1954–55, over DC’s bed at Castille

Every summer, Braque would dismantle the studio clutter and reassemble it on a more modest scale in the studio of his country house at Varengeville in Normandy, so that he could work away at his paintings in his studio, or simply study them until he was ready to return to Paris in the fall. The artist took pride in the artisanal ingenuity with which he rolled up his canvases and stacked them onto the roof of his car. “No rope,” he said. He also took pride in his skill at driving very fast cars; how he enjoyed the Rolls-Royce that his dealer had provided for him. He wished he had learned to fly a plane.

On their annual visit to Saint-Paul-de-Vence to stay with Aimé Maeght, the dealer Picasso disliked so much, the Braques would stop off at Castille. They loved the Avignon area, because, as Braque said, “the sky always seemed higher there than anywhere else,” and because it reminded them of Sorgues, the ugly suburb where he and Picasso had rented houses in 1912. It was there that Braque had stolen a march on Picasso by making the first papier collé, when he was off in Paris, thereby taking cubism a crucial stage further. This papier collé was the core of Douglas’s cubist collection, and he enjoyed having Braque tell the story of how he had found the wood-grained wallpaper for it in an Avignon shop—“Maybe they still have some in stock”—almost as much as Braque enjoyed reexamining this work, which can be said to have changed the course of modern painting.

In the summer of 1956, Braque had a specific reason for visiting Castille; he wanted to see how we had installed his Atelier VIII—the culminant painting of the series, into which he claimed to have put all the discoveries of his life. I had done everything I could to persuade Douglas that this Atelier was a kind of belated apogee of Braque’s cubism, and that it belonged by right in his collection; and everything I could to persuade Braque, including an appreciation of the painting in L’Oeil magazine, that its rightful place was on the walls of Castille. Douglas was very keen on the idea; Braque was too, except that he wanted an undertaking that this work, which he regarded as his masterpiece, would remain in France. Douglas gave him a promise to this effect, a promise he gave in good faith (at this point he had decided to leave Castille and its collection to the Courtauld Institute). In view of this promise, the price was extremely low, around 7 million old francs (in those days about $20,000). As things turned out, Atelier VIII did not remain in France. On Douglas’s death, it went to his adopted son, Billy, who had it shipped to Los Angeles. After Billy’s death in 1992, it came up at Christie’s in New York, where it fetched $7 million.

Braque seemed to like the way Atelier VIII looked above Douglas’s bed. Picasso had difficulty coming to terms with it. Whenever he visited Castille, he would seek it out and scrutinize it and kind of growl at it. Each time this happened, I would try to draw him out. “Comprends pas, comprends pas” was all Picasso would ever say. I suspect that it challenged him more than it baffled him. There were still things Braque could do that Picasso couldn’t. This must have rankled. Sure enough, two years later Picasso came up with a response—an oblique one that took the form of the most important of his variations on the greatest of all studio pictures, Velázquez’s Las Meninas. Picasso did not draw on Douglas’s colorful Atelier, but on one of the earlier monochrome versions. He envisioned Velázquez’s studio in the gray light and tactile space of Braque’s Ateliers.

DC with Fernand Léger in his Paris studio, 1949

Of the four cubists Douglas had chosen to collect, only one, Juan Gris, had died—too soon to meet the man who would devote much of his life to studying his work. Douglas’s scholarly catalogue raisonné of Gris’s oeuvre is the publication that does him the most credit. Rightly or wrongly, he felt he would have disliked Gris—“a wonderful artist, but a humorless whiner with terrible chips on his shoulder”—however, Douglas was fond of his widow, the beautiful Josette, who worked as a vendeuse in a French fashion house. She had also been the model for the magnificent 1916 portrait (bought for less than £100 at Christie’s in the late 1930s), which was the clou of Douglas’s Gris collection. Picasso, who had done much to encourage Gris when he was a poor illustrator, and quite a bit to discourage him when he became a successful cubist painter, regretted that he had never acquired any of his work. Hence his repeated efforts to persuade Douglas to sell him the Portrait of Josette—to no avail. Douglas left this masterpiece to the Prado.

To my surprise, Douglas’s eyes turned out to have been opened to modernism not by Picasso but by Fernand Léger: specifically Léger’s one-man show at Paul Rosenberg’s Paris gallery in 1930, when Douglas had been nineteen. He did not actually meet the artist until May 1933, when Carl Einstein—the pioneer historian of modernism and primitivism, who committed suicide when the Nazis invaded France—took him to Léger’s studio. Painter and patron became instant friends. For Douglas, this stalwart, outgoing, left-wing modernist from Normandy, with his tough-minded, architectonic theories and total lack of pretension, would remain Douglas’s beau idéal of a modern artist. For his part, Léger was delighted to have a new patron (the economic slump had wiped out his biggest collector), above all one who not only understood his work but bought it, wrote about it, and exhibited it. Léger’s intrepid wife, Jeanne, also took a shine to Douglas, as he did to her. She was one of the first of his Parisian friends I met; and it took me some time to realize that this frizzed, peroxided old lush had been a heroic Montparnasse beauty—famous in World War I for disguising herself as a poilu and, at the risk of being arrested as a spy or shot by a sniper, making her way to Verdun to have sex with Léger in the trenches. Her voice was as evocative as an old Edith Piaf record. Jeanne died a year later (1950), only to be succeeded by a bride whom Douglas described as “a totalitarian turnip.”

Léger mural, Les Trapézistes, oil on canvas, 1954, on the staircase at Castille, with two other Léger paintings below

In the course of putting together the world’s finest collection of Léger’s early work, Douglas had come to deplore the artist’s failure to find patrons for some of his more ambitious projects. To believe Douglas, many of Léger’s larger paintings of the 1930s had been conceived as murals—murals in which the tensions and collisions between identifiable objects and abstract forms would “destroy” the flatness of the wall on which they were painted. After buying Castille, he decided that Léger should paint a mural that would “destroy” the large wall on our staircase. On the occasion of his second honeymoon, which he spent with us in February 1952, the artist agreed to do so—in exchange for one of Douglas’s many Contrastes de Formes.

The only problem was that Douglas could not abide the artist’s second wife. Nadia was forever boasting about her important past: her closeness to Malevich—or was it Mayakovsky?—and the fact that she had been able to pee farther than any of the girls or boys in her village. Years later, Nina Berberova told me that Nadia was one of several Soviet women (another was the wife of the famous French novelist Romain Rolland) who had been encouraged to marry important cultural figures so as to keep them in the Communist camp. When I carried Nadia’s suitcases upstairs, she told me off. “You carry suitcase, you spoil domestic. You not porter. You fool.” Overhearing this, Marie, our cook, asked what Nadia wanted for breakfast. Orange juice: “Sorry, Madame, no orange juice.” Well, then, fruit: “Sorry, no fruit.” Bacon: “Sorry, no bacon, no croissant, no jam.” It was mortifying to watch Léger, who had abided by his Communist principles when Jeanne was alive and lived in a small apartment in a working-class district, being exploited by this Stalinist. “Léger very great man: he need country house near Paris; he need Riviera villa; he need private projection room…. In Russia great artist have all this.” Léger, who loathed all forms of privilege, seemed very depressed. For him, the whole point of films was going to the cinema and being together with le peuple and sharing their thrills and laughter and tears. He also said he preferred a sky with a lot of big white clouds, as in his native Normandy, to the monotonous blue heaven of the Riviera. Nevertheless, Nadia got her dacha, complete with projection room—in the valley of the Chevreuse, not far from the Duke and Duchess of Windsor—and a villa, the Mas Saint-André at Biot, where she would later memorialize her husband with a museum.

The mural on our staircase was a modified success. Douglas had chosen the subject from one of Léger’s suite of 1950 lithographs, called Le Cirque. It represented a couple of acrobats suspended from trapezes above a net. The artist did a slightly different maquette, which he handed over to assistants to execute on canvas. As decoration, the mural was fine—striking, colorful fun—but the image was not powerful enough to “destroy” the wall, and the brushwork did not bear the idiosyncratic stamp of the artist’s hand. How could it? Léger was seventy-four when it was painted and too heavy and shaky to clamber up ladders, which the size of the canvas (some thirteen by twelve feet) necessitated. His involvement seems to have been minimal. Shortly before he died, Léger came down to Castille to take a look. He strengthened some of the black lines, the net for instance, but this hardly entitled Douglas to claim, as he did when he sold the mural for a lot of money to the National Gallery of Australia in 1972, that it was a major late work by the artist’s own hand. Twenty-three years later, when the gallery invited me to lecture in Canberra, I was questioned about the possibility of assistants’ participation. The staff had gotten wise.

When Léger died in 1956, Douglas was extremely upset, not least at what he believed to be Nadia’s high-handed behavior. Whether or not he had any justification, he claimed that this accomplished pasticheur of her husband’s work had removed whatever painting was on his easel so that she could replace it with one of her own, a portrait of Mayakovsky, and pretend that at the end of his life Léger’s heart went out to Mother Russia.

Douglas disliked most of the young recruits to the School of Paris, but there was one exception, a Russian giant who drove a large camper up to our gates one November afternoon in 1953 and sounded his horn. “I am Nicolas de Staël,” he announced, “and I have an introduction from Denys Sutton [an English critic].” I let him in, a bit nervously. Although Douglas knew little about Staël, he was apt to dismiss him as just another of “those tedious nouvelle vague abstractionists.” How would the two of them get on? I need not have worried. Staël had been elected to the Czar’s College of Pages at the age of two, and his courtesy was more than a match for Douglas’s truculence. What is more, Staël’s charm turned out to be on the same scale as his frame—manic eagerness tempered with Russian melancholy.

Staël showed such understanding of the paintings on our walls, above all the Braques, that he won Douglas over in a matter of minutes. And then, far from being a hard-line abstractionist, Staël turned out to be in the process of making his way back to the figurative path. This ensured an instant entry into Douglas’s good books. For his part, Staël, whose work had just begun to sell, was delighted to have found a new, famously discriminating fan. Over the next two and a half years he would give Douglas and me a fine, small group of his paintings and drawings. Pride of place went to a smashing landscape of Agrigento (1953)—vermilion roofs against a purple sky—which the artist had picked out specially for the “château des cubistes.” Hung at the foot of the stairs, it vied with the Léger mural on the landing above.

Nicolas became a regular visitor. Douglas and I relished the prodigious way this giant ate and drank and laughed and groaned. He was extremely articulate, not only about painting but also about literature—Henry James in particular—and turned out to have a number of poet friends, among them the celebrated René Char. But Staël’s principal passion was Braque. He regarded himself as Braque’s disciple and had taken a studio around the corner from Braque’s house on the rue du Douanier, so that he could have constant access to him. Just as well he did: one day Nicolas went up to Braque’s top-floor studio and found the frail old painter in the throes of an emphysema attack. He summoned help and saved his life. The affection and respect were reciprocated. To my knowledge, Nicolas was the only young artist Braque spoke of with unqualified enthusiasm: he accepted him as a follower and occasionally subsidized him when money ran out. As for Picasso, Nicolas knew him and greatly admired him—but from afar. He liked to describe their first meeting at a Paris gallery toward the end of the war. Looking up at this giant towering over him, Picasso had felt like a baby. “Take me in your arms,” he had said.

Nicolas de Staël in his Paris studio, 1954

When Nicolas began frequenting Castille, I was writing the first of two books on Braque, and I profited greatly from his practical experience of Braque’s theories of “tactile space” and the interrelationship of color and texture. Nicolas’s exploitation of impasto derived from Braque; so, less obviously, did the flat washes of color and infinite gamut of grays and blacks in his later work. More of a surprise was his obsession with the etchings of that rare and mysterious seventeenth-century Dutch artist, Hercules Seghers, whose prints were the inspiration for some marvelous drawings of boats that he gave us. After dinners at Castille, Nicolas would drive off into the night in the by-now-familiar camper, a kind of traveling studio, which he had filled up earlier that summer with his family and canvases and driven to Sicily—hence our Agrigento painting. On the way back to Ménerbes, he would stop by the roadside and make notes by moonlight. His attention had been caught by “the nothingness” of a particular stretch about two miles down the road from Castille. This was the inspiration for his minimal Road to Uzès landscapes: six irregular segments of thinnish paint in dullish blacks, greens, and grays is all they are, but these segments combine to form a vanishing point, toward which Nicolas, a maniacal driver, seems in my imagination to be forever heading.

In the winter of 1953–54, Douglas and I became regular visitors to Le Castellet, the fortified seventeenth-century house Nicolas had recently acquired at Ménerbes. It crowned one extremity of this hilltop village like the prow of a man-of-war, and in its imposing, fortresslike way it was eminently suited to this scion of the chivalrous Staël von Holsteins. Nicolas had done away with his predecessor’s fustian decor and laid bare the medieval masonry of Le Castellet’s vaulted rooms, which he furnished with a few bits of austere, Escorial-like furniture. “The only aristocrat since Delacroix who knows how to paint,” Douglas said after visiting Le Castellet for the first time. And, true, the fastidiousness and cool Baudelairean dandyism of his style and the panache with which he attacked a canvas did have something aristocratic about it. Thank God for the Revolution, Douglas said. If Nicolas had inherited the family palace on the Nevski Prospect, he would never have been such a great painter.

Nicolas was one of the very few modern masters who had actually starved, not so much during his childhood as an orphaned refugee, but during the war, when he was in his late twenties and lived on next to nothing in Nice with a wife who was dying of tuberculosis. Like many another White Russian, Nicolas was too proud and fatalistic to hold his misfortunes against the world. Nevertheless, the scars went deep. As Douglas wrote, “He was a complex and in many ways contradictory character: autocratic, exacting, exuberant, morose, charming, witty and uncompromising…. He lived out his life between a series of violent extremes…. Pride would suddenly be replaced by humility, self-indulgence by asceticism, exaltation by gloom, uproarious laughter by withering scorn, supreme confidence by serious doubts, excessive work by deliberate idleness, great poverty by riches.”

Marcelle Braque put Nicolas’s dilemma in a nutshell: “Watch out,” she told him, “you staved off poverty all right, but do you have the strength to stave off riches?” He did not. This Tolstoyan hero had always been beset by Dostoyevskyan demons, but after his sudden, huge success in America—a sharp-eyed friend of ours, Ed Bragaline, had been so impressed by his first New York show that he had bought several works for himself and persuaded his collector friends to follow suit—the demons got the upper hand. Money enabled Nicolas to indulge his Russian largesse to the full, but there was a certain desperation to his extravagance. One winter evening when he was on his own at Ménerbes, he invited Douglas and me to dinner. To start with, there was a great slab of foie gras. Then came a large turkey, which Nicolas had stuffed with a kilo of truffles. The three of us washed this down with most of a case of Cheval Blanc.

In the fall of 1954, Nicolas left Ménerbes. He had become infatuated with a young married woman called Jeanne—a protégée of the poet René Char. According to Nicolas, Jeanne was prepared to have an affair with him, but was not ready to leave her husband or show her lover much in the way of affection. When Nicolas dined with us on New Year’s Eve, he described the hellishness of his situation. He adored his wife and family, but could not live with them; he resented his recalcitrant mistress, but could not live without her. Meanwhile, he had taken an apartment on the ramparts at Antibes, and was experimenting with a fresh, more figurative approach to a whole new range of subjects. Besides being tormented by chagrin d’amour, he was tormented by doubts about the new direction his work was taking.

Toward the end of February 1955, Douglas and I drove over to Antibes for lunch. Nicolas was in the depths of despair, and no wonder. The apartment looked across at Vauban’s sullen-looking fort, which reminded him of the Fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul that his father had governed. It might have had a certain charm in summer, but on this dismal winter day the gray waves crashing onto gray rocks under a gray sky intensified the melancholy. “The noise of the waves is driving me mad,” Nicolas groaned. And yet he had come up with some of the most exhilarating work of his career. Never had he laid on his color more luxuriantly and sensuously than in that mysterious paean to painting, The Blue Studio, which I would come to see as Nicolas’s farewell to art and life. Subject and medium seem to fuse into each other, as in Braque’s work. Douglas could not adapt himself to this sudden leap ahead, and this made him cross and critical. “It’s all gone so soft,” he said, evidently blind to the beauty and originality of the new paintings. Nicolas, who was in desperate need of reassurance, remonstrated with Douglas for his severity. I did my best to lower the tension by praising their symphonic sweep and orchestral color, but Douglas would not desist. I left them at it and went over to study a canvas that seemed the very essence of anguish: a vast, fearsome painting of seagulls flapping over tossing waves. On the same wall a window gave out onto an identical scene of gulls, grayness, and gloom. Just like the crows in van Gogh’s ominous cornfield, I remember thinking. In retrospect, it is easy to see that this painting was a cry for help. Why didn’t we respond to it?

The sculptor César in his workshop ca. 1955

Three weeks later, on the evening of March 18, Nicolas threw himself headfirst off his terrace, and landed just short of the rocks below. He died instantly. He was forty-two, and had barely begun to exploit his new-found lyricism. A few months before his suicide, he had sent me a bundle of collages to choose from: figures, still lifes, and a bullfight made of torn-up colored paper. I had not decided which ones to keep. Now that Nicolas was dead, Douglas suggested I hand all of them over to him “for safekeeping.” Safekeeping indeed! I never got them back. After I left Castille, he used them to make swaps with dealers.

The only other young French artist to be included in Douglas’s collection was the Marseille sculptor César Baldaccini, who preferred to be known simply as César. I had fallen for one of the welded scrap-metal pieces—a large Fish—in his first show in 1955 and had used up most of my savings to buy it. At first Douglas had been inclined to dismiss the Fish as too indebted to Germaine Richier. However, he came around to the power and originality of César’s work after visiting the artist—a tiny tornado of a man with an enormous mustache and a quintessential Marseille accent—in his studio. On his way south a few months later, César stopped off for dinner at Castille. It must have been after a bullfight. Picasso was there, and given all that he had achieved with welded metal took a great shine to César as well as to my Fish, which had a place of honor in the hall. The following year, when César had a show at Vallauris, Picasso questioned him at length about his welding methods and nearly bought the iron Turkey, which Douglas later acquired. César was virtually the only young sculptor in whom Picasso took any interest.

César, Fish, welded metal, 1957; stolen from JR

César was proud of having grown up in direst poverty. To demonstrate how dire his early days had been, he took us on a visit to his father’s shabby little bar in a section of Marseille so poor that cigarettes were sold individually rather than by the packet. And then, as a contrast, he took us on a short cruise off Marseille harbor on a rich friend’s well-appointed yacht. The outing was intended to demonstrate to us, as well as to César himself, the conspicuous change he had wrought in his circumstances. It was done with irony and panache. People seemed to have more fun in the bar than on the boat.

This captivating bush baby of a man, with his dynamic energy and joie de vivre and ever more eye-catching style, soon became a major star of le tout Paris. In 1960 he had such a success with his compressions—automobiles crunched in a huge scrap-metal compressor—that chic Parisians lined up to have their Mercedeses and Alfa-Romeos transformed into pieces of sculpture that were rather more valuable. At almost exactly the same time, John Chamberlain, the New York sculptor, unwittingly started doing almost exactly the same thing. There is a subtle difference. The Frenchman’s mechanical compressions are that and no more; the American’s have a look of artistic contrivance. Douglas refused to let César crunch his Citroën; he had become too fond of it. In the mid-1950s, César took to using a pantograph, an instrument that enables an artist to replicate his work on a larger scale. He would make a mold of his thumb or the breast of a go-go dancer and blow it up to monumental proportions. He also took to playing around with liquid polyurethane that sets in half a minute. He would throw a bucket of this new material down a flight of steps and the stuff would jell into instant “action” sculpture. Brilliant showmanship is about all one could say of these crowd-pleasing expansions.

DC with Renato and Mimise Guttuso at Castille, 1954

César’s Fish was one of the few possessions I succeeded in rescuing from Castille. Alas, I managed to lose it all over again. Shipping it back from Paris would have entailed so much expense and red tape that I left it on loan to a funny, feckless friend of mine, Jean Léger, the artist’s great-nephew. When, a year or two later, I tried to get it back, Jean turned out to have contracted AIDS. He said he had grown so fond of my Fish that he wanted to keep it a little longer. In view of his illness, I refrained from pressing him, but after his death I tried to extract it from his estate, only to discover that his Haitian roommate had made off with it. César was also concerned, as he wanted to have the Fish cast in bronze for an edition he proposed to put on the market. He asked his lawyer to help, but the roommate turned out to have gone into hiding, and before we could take the necessary action, he, too, had died.

Another regular visitor to Castille was Renato Guttuso, then the most famous social realist of his day, now virtually forgotten outside his own country. Douglas worshiped this Sicilian maestro. He deluded himself that Renato was a modern Delacroix who had the virtuosity and ideology to breathe new life into the fustian genre of history painting and tackle such overexploited themes as the horrors of war in an eye-catching new way. Douglas maintained that Renato’s verismo approach was more relevant to modern life than abstractionism, which he chose to see as “very old hat…. World War II had killed it off. Why ever resuscitate it?” It helped that Renato was handsome and magnetic, with fire in his eyes as well as his belly. Charisma had won him a seat on the Central Committee of the Communist Party, as well as the hand of the former beauty Contessa Mimise Bezzi-Scala, a delightful woman but a most inappropriate wife for a prominent Communist. Mimise was ineffably ladylike—always dressed as if she were about to launch a ship rather than take part in a political rally.

Renato Guttuso, Boogie-Woogie, pencil, 1953

Apart from Edouard Pignon, Guttuso was the only one of the younger Communist painters with whom Picasso felt comfortable. Jacqueline and Mimise also got on well; boredom with Communism was a bond. Douglas and I used to join the Guttusos at La Californie, and sometimes return with them to Italy. In the fall we would stay in their villa near Varese. Mimise loved people who loved food and would serve us the best of all salads: porcini mushrooms or, better still, the orange ovoli, with shavings of Parmesan, white truffles, and some good olive oil. Winters we would visit the Guttusos in Rome, in their elegant apartment in the Palazzo del Grillo, hung floor-to-ceiling with a well-chosen collection of modern paintings and drawings, including several Picassos. Summers they would visit us. We would have a roll of drawing paper ready for Renato. After dinner he would ask what he could draw for us. “A disaster,” Douglas would say. “The Black Hole of Calcutta, a fire in a lunatic asylum.” Renato would usually come up with the same writhing figures—dynamic heroes and villains, not unlike himself, and a lot of big-bottomed women with spaghetti hair. Since I owned some fanciful, verre églomisé furniture that had been made for an eighteenth-century folly, the Villa Palagonia in Bagheria, near where Renato had grown up, he would also do drawings of the villa and its grotesque sculptures, which Prince Palagonia had commissioned in the hope of inducing a miscarriage in his wife.

Renato’s after-dinner displays of virtuosity made one wonder whether his more serious work might not have been conceived in the same simplistic spirit. His sense of tragedy seemed as mechanical as a wind machine on a movie set. I had admired some of his earlier paintings, not so much the overwrought scenes of revolutionary fervor as the gutsy images of popular life—people in cafés, at dance halls, or at the beach. Renato gave me a fine drawing for his polemical set piece Boogie-Woogie—a denunciation of what was then called “cocacolonization,” as well as a mockery of Mondrian—but the message comes across scrambled, and the image seems to promote what it purports to attack. I was not alone in finding most of his later work too hokey to take seriously. Before Mimise died, Renato had taken up with another ravaged contessa, but whereas Mimise was infinitely supportive, her successor turned out to be a voracious tigress, to judge by the references to her in his work. He sent this woman a drawing every day of her life. Toward the end, social realism gave way to tedious allegory, and prelates hovered. Renato’s death left his reputation in limbo and his estate at the mercy of bickering heirs. Douglas had long since sold his extensive holdings of Renato’s work. With them vanished any faith he had in the long-term prospects of social realism.