Chapter 6

I HAVE BEEN TOLD that very little has changed in the auditorium of the Binghamton High School since my father was there. The curtains, the wood flooring on the stage, the old windows, now covered, and even the chairs where my dad and his friends sat are all still there.

And so it takes little imagination to visualize that day in January 1943 when my father and his classmates graduate midyear. Their joy, perhaps naive but not curtailed, despite a war that will soon alter the lives of so many of them.

I see them beneath that downpour of light, their diplomas hoisted high in the air as they walk across that stage. An orchestra plays “Pomp and Circumstance,” just slightly off-key. There are smiles and laughter and shouting to family and friends waving programs madly from their seats below.

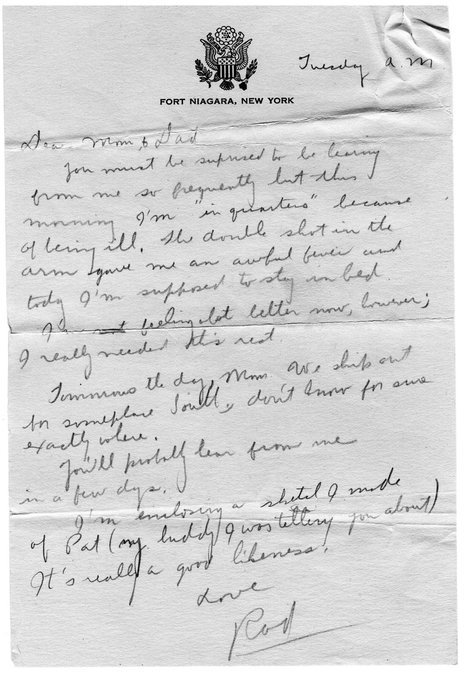

The next day, at seven a.m., my dad, along with some of his buddies, stands in a long line outside the recruiting center on Chenango Street in downtown Binghamton and enlists in the U.S. Army’s 11th Airborne Division. He is barely eighteen years old and the letters he will soon begin writing home from training camp are achingly reflective of his age:

Friday February 12 1943

From HQ C) 511th Parachute Infantry

Dear Mom & Dad,

So much has happened and there is so much to tell you that I hardly know where to begin. First I am at Camp Toccoa in Northern Georgia. I travelled in a Pullman with 40 other guys. The Pullman has a swell sleeper and excellent dining car. It wasn’t a regular troop train—merely a car added to a regular train . . .

The story of how I passed my Paratrooper tests today is really one for the books. You know it’s tough as hell to get in and over forty percent flunk out at the start. I went right through physical passing everything until I reached the final officer who looked over the physical report. He looked at my weight and said, “I’m afraid you are just a little too light and small.” Well, Mom, I was so damned anxious to get in I went through a regular Bob {brother} routine. I begged, I pleaded, I beseeched—and it worked with the help of my Corporal who put in a good word for me. He erased the original rejection and put down “O.K.” My Corporal said I was the littlest damn paratrooper he ever saw. Later on he told me that the Major and the Captain who forced the final review board here remarked about my “guts” and said I should do O.K.

Here’s my tentative training plans: thirteen weeks basic training and four weeks jumping school. And here’s a surprise, folks—Mom I think you’ll like it. I’ve been selected for radio training. I’m to take charge of one of those walkie-talkie radio sets after jumping. I was chosen for this particular job because I had a very high mark on a sort of radio sound test . . .

Now after I finish my jumping school someplace I’ll be sent to radio school someplace so you won’t have to worry about me being sent out of the country too soon . . .

God this outfit is tough. I’m in for thirteen weeks of the hardest training the army offers, but I’ll be a far better soldier and a better man, believe me.

Well. Mom, I’m writing this Fri night but I’m not sure when I’ll mail it. You see I’m only barracked in this particular company temporarily and there’s a chance I might be sent away from here for my basic training in a short while . . .

Sunday February 21st 1943

Dear Folks,

Arrived here at Camp Hoffman in North Carolina this morning at eight o’clock. I’ll probably be stationed here for at least six weeks, so you can write me here, preferably airmail. We’ve sort of been taking it easy these past few days—preparing for the trip which involved the transporting of our entire regiment—almost two thousand men, meant a complete termination of training. Tomorrow, however, we’ll shoot back into training; I think I’m getting a little bit accustomed to it now, however.

The weather here today was beautiful—sunny and about 68 degrees. They tell us we’ll probably see colder weather though, before spring sets in.

I wish you’d send me the following:

Shoeshine kit

Sewing kit

Pen & pencil set

Money belt

Pipe cleaners

Underwear (I don’t like the GI kind)

I got a letter from Bevy the other day—also one from Muriel. It’s really a thrill getting your name called off during mail call. It’s also an awful let-down if you go away day after day with no letters. Please Mom, write and write and write and tell me all the news from home.

Gosh Mom and Dad, there’s so darn much I’d like to tell you I can’t get it down on paper—if only we could discuss it over one of Mom’s home cooked meals—that would be paradise . . .

. . . I’m a member of the 511th Parachute Infantry regiment . . .

I’ve got quite a bit of money from Dad’s ten and my partial pay often more. I get paid approximately 30 dollars the end of this month after my insurance, laundry and war bonds get deducted.

I’m going to send at least 8 or 10 dollars home every month—I have plenty for myself. Here’s what you do Mom. Put the money away for me until I’m eligible for a furlough, then I’ll send for it and have plenty of money to get home. Please use as much of it as you want in case you run short!

I’ve been sort of thinking Mom, I’m told that we had a chance for a furlough but there was just as much of a chance that we might not receive any. I couldn’t take going overseas without seeing you once more so I was wondering if it were plausible to think that you and Dad might travel south to see me. I’ll be getting 3 day passes after I finish my jump training at Fort Benning, Georgia (in June). That wouldn’t be enough to get home but I could go to Atlanta, 94 miles away and meet you for three days. I realize it’s war time but you could use the dough I’ll be sending home and perhaps Dad could get away and you could travel by train. Oh hell, I guess I’m getting just pipe dreams. They are thoughts, however! (This sounds like Aunt Rose.)

How’s business? Is meat getting harder to secure; down south we read in the papers all the time of big meat concerns going out of business because of the security of meat and prevalence of Black Markets. Please let me know what’s going on.

Well, I still can’t say I’m actually happy in the army. For my first six weeks I have almost complete lack of freedom—we march to meals, march to the PX, march all the time and are restricted to our company area (almost 300 yards).

Well, please write often and send me the stuff I asked for when you get the chance.

Love to the both of you,

Rod

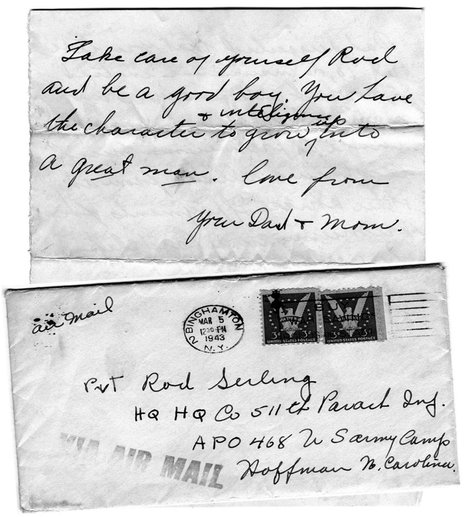

In a letter a few weeks later, after not having heard from him, his mom writes:

We wondered and worried where our little soldier boy was . . . I’ll be honest with you, we weren’t so enthusiastic about you joining the paratroops. It is a very dangerous service to be in. However if that is what you wanted, I know you will do well in it. We have that confidence in your ability . . . We miss you too Rod. I miss having to scold my boy for throwing his things around. I have put your thousands of airplanes away in a box. On your first furlough you will have my permission to count them all on your bunk. I didn’t disturb them, they are just as you left them . . . I will write you often and so will Dad . . .

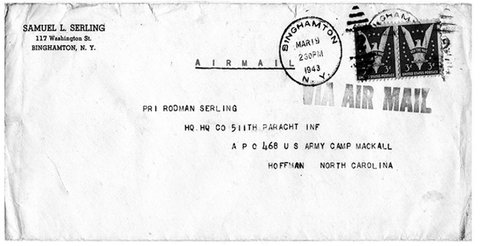

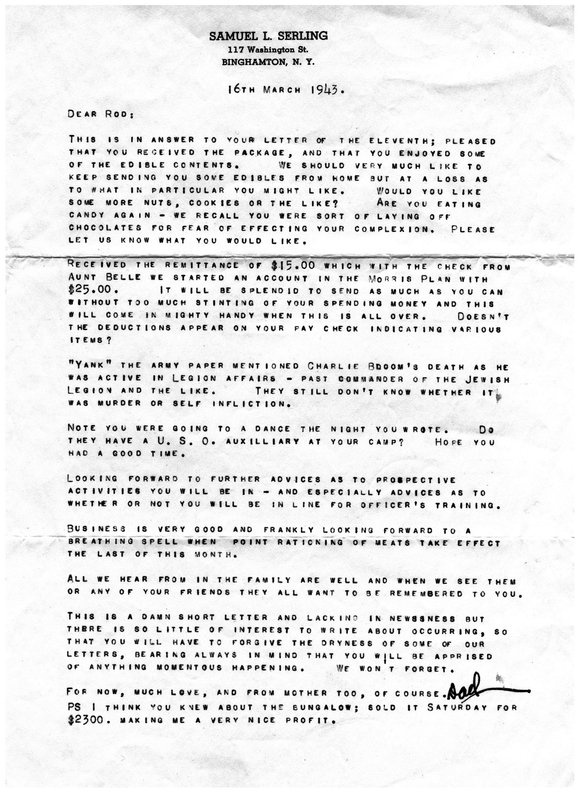

March 11th, 1943, from his father:

Dear Rod:

An individualized son to father letter deserves a prompt father to son answer—and that immediately—yours being received just this morning.

Your assurances of being happier naturally makes me much more contented with your lot. I have experienced many qualms knowing that you were pretty young to become too soon acclimated to such a drastic change from your former sheltered lifetime. These qualms were assuaged by the knowledge that the C.O. in Niagara was right when he stated that you had the “guts”—or more elegantly—“What it takes.”

I appreciate it must get pretty monotonous sticking to the same routine but it will have its compensations, we pray. Your response to Mother’s question as to whether you would enlist if you were to do it again—“No” does not surprise me in the least. Far be it for me to say, “I told you so.” But I do not agree with you. The fact that you enlisted gives you some advantage, even though it may be questionable, over the draftees. Your so-called “guts” asserted itself when you enlisted . . .

My dad sends his parents a copy of The Pictorial Review of the 511th Airborne. “To Dearest and Dad by their son Rod.” The combination of unwavering patriotism and questioning of authority and bureaucracy that so characterized my dad’s life is evident. In a written dedication he refers to the paratroops as: “The greatest fighting unit in the world,” yet throughout the printed copy he amends his own comments to offer the “true” story. He underlines the printed sentence: “At no time is any attempt made to push, cajole or talk a student out of a plane.” In the margin he writes: “A lot of bull—the gentle art of pushing, shoving and ‘Squeezing out’ is commonly employed!”

Among the yearbook-like autographs covering the final pages of the 511th Pictorial are such lines as: “Loads of luck to the guy that brings laughter to our barracks.” One sergeant writes: “Good Luck and Happy Landings, Short Stuff.” Several people refer to him as a swell guy or swell fellow and one writes: “Here’s to a swell little guy—may we meet after this mess is over.”

March 14, 1943

Dear Mom and Dad,

. . . Still doing ok with the paratroopers. When I’m marching quick time (with my exceedingly short legs) and feel so tired I don’t feel I can move any further, I always do. And when my arms are tired and sore from holding my long M1 rifle and I figure I can’t hold it up anymore—I always do. I don’t know whether it’s guts, determination, or plain stubbornness on my part but I’m always in there and always will be . . .

The only news is that I think I leave for Fort Benning in about three weeks. There I take my jump training, which is the most exciting part and really the climax of all paratroop training. I spend three weeks in rigid instruction and then take five parachute jumps from 8,000 to 800 feet respectively out of a plane. Upon completion of five jumps, I win my wings and boots—that will be the day.

After that I come back here or else go to some camp for six weeks radio training. I’m sure to receive some stripes after my technical training but OCS (Officer’s Candidate School) seems pretty far away. It’s tough to get into and my age and rather youthful appearance is against me. My lieutenant told me that though I’m really not worrying about it since it’s too premature to be important as yet.

Spent the whole morning washing clothes. I’m really quite adept at it now. The laundry takes two weeks and I’m usually so short of clean clothes I need to take on the job myself.

Had a dance here a few nights ago—girls came from all around and I met a cute brunette who’s a nurse. I got a date with her my first pass into town. We also start getting movies in camp next week.

I’m all tanned up—it’s been very warm here.

The underwear you sent comes in handy.

Can’t wait until I get to Benning. There I have evenings free and also weekends. I wrote Sue for her mother’s address, maybe I’ll be able to meet her in town.

Heard from Bob? I’m awfully anxious to hear what his assignment will be. Guys tell me here that when a big group leaves Woltes(?) it very often means an overseas assignment so maybe it’s just as well that he didn’t leave with his group.

Well folks, write me as often as you have been and give my best to everybody.

He closes the letter with:

PVT Rodman wants: towels, hangers, Fanny Farmer candy, another cloth for shoe shining, flashlight, Garrison belt.

Best Love,

Rod.

After a brief time in the infirmary, he writes home about his doctor, a Jewish lieutenant. “He attends my ward. He’s about 37, married and comes from Manhattan. We’ve had some nice talks and he tells me one of the Jewish captains is going to conduct Friday evening services for us because there is no Jewish chaplain.”

He also expresses his homesickness: “Mom when you told me about seeing me if possible this summer, it boosted my spirits right up. I’m so damn homesick, the very thought that I’ll see you—even if months from now is something I can look forward to and think about...”

In one of his mother’s letters, she writes:

Are you getting used to the service army training? Are you happy, Rod? I often stay awake nights wondering what my boy is doing. I think the happiest day of my life will be when this war is over and our boys are home again.

She signs it: “Lots of love to the nicest boy I know.”

She includes a note from Tony, the dog. “I miss you so much, bow wow.”

His father writes (in part):

4th April 1943

Dear Rod,

Seven-thirty Sunday night and here in the office writing you. Mother is leaving for Syracuse on the nine-ten bus as Uncle Si passed away this P.M. and will be buried tomorrow. Mother is naturally broken up about it but can do naught else but be philosophical about it. Will drive up myself to attend the funeral tomorrow. Writing tonight as I realize I will be too busy tomorrow. And I don’t want you to be without mail for too long a period . . .

Will act on your requisition by forwarding a package tomorrow which will contain considerable reading matter; a shoe-shining outfit and if I can rustle up some brownies will do so; if this latter item is not obtainable you will have had at least the package of candy mother sent you last week from your friend Fannie’s and the brownies will wait until mother can take care of it herself . . .

Had an extremely profitable month last month, but still playing with the idea of disposing of the business . . .

Nothing further to add, except to ask that you keep writing as often as you possibly can; send us your requisitions for whatever you want and keep well and happy.

Much Love,

Dad

A week later my grandfather writes my dad a letter that, in part, could be any note sent to a child who is simply away at summer camp.

12th April 1943

SERLING’S WHOLESALE MARKET

Food Distributors

117 Washington St.

Binghamton, New York

Dear Rod,

’Twas swell hearing from you Saturday by phone and to know that you are getting along so well. Any Sunday morning that you can we would be only too tickled to have you call. Don’t let a little thing like the loss of your wrist watch bother you; there are so many big things to think and fret about now. Sent you a package to-day containing:

25 Funny Books

1 wallet—(Sue’s) to use for dress

1 wallet—mine for rough wear

1 carton with packing, stamped and addressed to forward your

glasses to Hills, Schenectady for replacement of lens you broke.

1 wallet—(Sue’s) to use for dress

1 wallet—mine for rough wear

1 carton with packing, stamped and addressed to forward your

glasses to Hills, Schenectady for replacement of lens you broke.

Your name is on the service board at the center and also at the court house.

You requisitioned candies and cookies in your last letter, but this crossed a shipment on its way to you. Will send you more right a long, and don’t hesitate to keep your orders coming and will fill to the best of our ability.

Still working on the potential disposition of the meat business. Don’t know how successful I will be but will keep you advised of anything momentous occurring—naturally.

Point rationing in our business is considerable of a headache. Taking twice as long to wait on the trade at retail and much more time taken up in billing out the wholesale what with having to figure the points per pound which the instigators of the system had to make it as hard as possible by stipulating fractional points so that it is exercising my mathematical acumen to figure out the fractional points and the fractional ounces. Can you visualize how nervous I would be on a Saturday morning? Taking it all in my stride, however, my nervousness being assuaged somewhat with the hope that it won’t be long before someone else will have to take it and all the rest of the grief this type of business is subject to.

Nothing further to add except much love as usual.

Dad

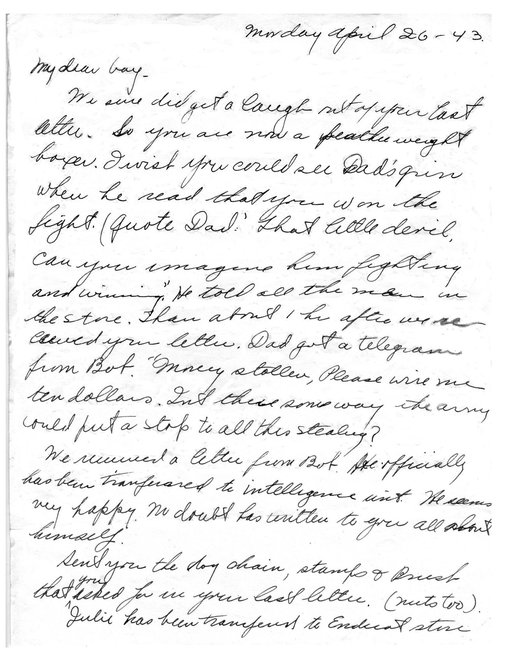

April 1943, from his mother:

I watch for the mailman every day, when he hands me a letter from you or Bob he sure gets a smile from me. I am proud of you honey. All my friends say, “Don’t you worry about Rod. He will get any where he wants to. He has what it takes. Personality Plus.”

That same month—a letter from his friend Julie Golden:

Jack talks as if you’ll be overseas this month. My God, you weren’t kidding in March, were you? Just how long before you’ll be going, Roddy, or don’t you know? If it’s soon, I can’t think of a helluva lot to say to you. Personally I wish you’d never have to go, but that won’t help things. And the two guys in your regiment getting killed won’t help things either. They got theirs merely in training, not in conflict. It’s sad and sickening, but I don’t think I’m going to worry about you. You can take care of yourself as well as if not better than anyone I know, and I’m satisfied that nothing is going to happen to you . . . Write soon, Rod. If you’re being shipped, write sooner. You know I wish you the best luck in the world Private Serling. See you later . . . Julie

During basic training, my father wants to make a little extra money and earn some privileges. He decides to take up boxing and is trained by an ex-pro who had sixty-eight fights of his own.

My father has a lucky streak and wins seventeen fights in the flyweight division.

A week later, May 1, his mother writes, “So you are the official champion boxer. What a tough lug you must be. Don’t you dare get your good looking face all slammed up.”

In the eighteenth fight, a professional boxer breaks his nose and knocks him out in the third round. My father gives up boxing. He doesn’t give it up in his imagination, though. Boxing will be a recurring theme in several stories to come.

A newspaper, praising his boxing ability, says that he has “the ring in his blood.” Years later my father says, “In truth, I’d left a helluva lot of my blood in several rings!” (I remember him pointing to his nose one time, indicating to me where it was broken in two places.)

There is a gap here where letters exist, I am certain, but I don’t have them and then on December 2, 1943, Sam writes my father:

Dear Rod, Naturally we were disappointed to get the information that the leaves have been cancelled, but when we philosophized of the wrench the leave-taking always gives we were somewhat reconciled. Then too, while we were more concerned over the way you felt, we must remember this is war—and disappointments, heart-aches and other miseries must be almost constantly borne, hoping and praying always that the compensations when it’s all over will heal the ravages caused by the miseries . . .

If we could only be sure that you do not feel too keenly the disappointment of not getting home once more before you leave we could be more easily reconciled. Perhaps we were too devoted parents in our constant efforts to shield you from disappointments so your training in this direction is somewhat lacking. I hope I haven’t failed as a father. I know I have been lacking in lots of ways. I have been harsh and allowed my unreasonable temper to control my better judgment—which I should have had. Another complex which I very much regret is my being undemonstrative. I never dreamed that you wanted to get closer to me; it would have been worth everything to me to let you indulge your impulses or inclinations, but your not appreciating my complex and my not knowing your desires, we both missed out. Pray God I will have the opportunity to change this . . .

My grandfather goes on to talk about cutting back his business and how he is “beginning to see the possibility of a well-earned rest.” He writes, “I need one badly—at least a mental relaxation. Physically I never worked too hard, but would have preferred this to the constant strain mentally.”

Sam closes the letter: “I hope this letter doesn’t strike you as maudlin. There I go again letting my complex rule my judgment. But, Rod, I want you to know that no father was more fond of a son than I am—always have been—and always will be of you. Forget, please, the infrequent lapses into actions, reprehensible and always regretted. All My love, Rod, in which mother of course joins me.”

The letters to and from my dad’s parents then continue: “Hello to our dear boy . . . we miss you . . .” until one day, training is complete and my father is put on a troop ship and sent to the Pacific as part of an assault and demolitions team.

And here the letters stop.