Chapter 16

IN 1962, MY FATHER is thirty-seven years old. That spring, CBS drops The Twilight Zone at the end of its third season, after 102 episodes have aired. They had not yet found a sponsor for the fourth season, and CBS had scheduled a new show in Twilight Zone’s regular time slot. My father is offered a teaching position at Antioch College, his alma mater, in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Although CBS later renews the contract for the series, my dad accepts the position at Antioch before he learns of Twilight Zone’s resuscitation:

Antioch is liable to drop my option, too. I’ve never taught before. If that happens, and if CBS doesn’t go ahead with the hour show, I may go fishing the rest of my life. I have three reasons for accepting the position. First is extreme fatigue. Secondly, I’m desperate for a change of scene, and third is a chance to exhale, with the opportunity for picking up a little knowledge instead of trying to spew it out . . . I need to regain my perspective, do a little work and spend the rest of my time getting acquainted with my wife and children.

I am in the second grade, and Jodi in fifth, when we move to Ohio. CBS does renew The Twilight Zone but changes it from a half hour to an hour-long format, perhaps because “a bigger Twilight Zone might attract a bigger audience.” The show will air on a Thursday (rather than a Friday) night. Although my dad will still be writing a great number of the scripts, he decides to take a step back from his day-to-day involvement.

We pack up the dogs, cats, and our two pet rats and head east. Although my sister and I are sad about leaving our friends, we are all excited about this move and recognize it’s only temporary; we’ll be home again in six months.

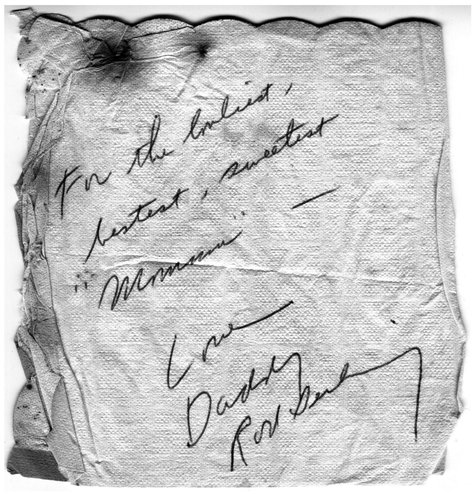

On the flight to Ohio, as on many of the airplane trips we take, my father and I play cards. We play “Go Fish,” for money, and I am up to $40 before I lose it all. We also write notes back and forth and play Tic-Tac-Toe and Hangman. After a while, having reached his saturation point, he writes me, “No more notes. Daddy-boy is busy reading.” I look over across the aisle and both my mother and sister have fallen asleep.

In Yellow Springs we rent a white, two-story house. When we are first settling in, my father leaves to go to the college, and my mother tells my sister and me to walk around the block. Jodi runs ahead and I become hopelessly lost. All of the streets look the same, all of the houses unfamiliar, and all of the dogs look ferocious. By the time I find my way back, it is late. I am terrified and in tears.

I have only a few memories of specific rooms in this house, the threadbare stairs we run up and down each day, and the bedroom that, for those few months, is mine. It has dormers and red wallpaper that I love. It is an old house, and I pretend we are living in another time.

The elementary school is close enough that we can bike to it and return home for lunch. For the first time we are allowed to call our teachers by their first name. My teacher, Mary Chase, sometimes brings her dog to school—a basset hound who obediently sits in the corner of the classroom looking adorable.

Jodi and I make friends fairly quickly, but before we do, we sometimes settle for each other. One of our favorite things to do is to build houses for our little two-inch Steiff bears. We build the houses out of boxes. The liquor store boxes are the best because they have dividers that make for ready rooms. We use contact paper for wall paper, or sometimes paint the walls and floors and fill them with tiny doll furniture. We lie on her bedroom floor or mine, in our flowered pajamas, rearranging rooms, talking in “bear voices” as they travel from one house to the other.

Eventually we plan our weekends and overnights with friends. My best friend is Roz and she understands when, on Saturday mornings, I have to leave early. I don’t tell her the exact reason but it is because I have discovered that I love vacuuming and I can’t wait to get home so I can vacuum all of the rugs.

When I come in, my dad is sometimes on the couch in his light blue robe, reading the newspaper. He looks up at me over the paper, smiles, and picks up his feet so that I can vacuum the area before him. Often, though, he is upstairs working while I, still wearing my yellow winter coat, lug that huge Hoover vacuum throughout the house, backing away as I go so as not to leave a single footprint.

One of the classes my dad is teaching is a night class, “Drama in the Mass Media.” I feel his absence profoundly in the evening and stand by the window, watching, waiting for him to come home.

Often he has to fly back to California, balancing work on both coasts. I hate it when he is gone. My mother must, too. She seems happier when he’s around. My sister, as is usual for her, is busy, off with friends much of the time, probably missing her horse. We haven’t played with our bear houses for a while; the bears sit in the same position we last left them, posed and motionless in our absence.

We are all aware of the quiet, still house when my father is away. Even the dogs Michael and Maggie stare at the door, waiting, joining us when Jodi and I jump around him when he returns.

Some weekend mornings we spend time with old family friends who live in Yellow Springs—Dorothy and Jim Mitchell. “Aunt Dottie” and “Uncle Peabody.” We name Jim after a cartoon character who, like him, also bird-watches. We play with Dottie’s makeup, loving her bright red lipstick and blue eye shadow. We make snickerdoodle cookies, eating them hot out of the oven, and later we roll around with their dalmatian Binky.

Dottie remembers my dad’s students loving him. Recently she reminded me about the time my dad asked her and Jim to come over to play bridge. ”The snow was about a foot deep. We told him we wouldn’t be able to get there. Well, he said he would come get us and he did—in that sorta pink station wagon he had.”

That Christmas we go with Dottie and Jim to choose a Christmas tree. A Boy Scout goes with us and helps us cut down the tree. My mother is filming with a heavy 8mm camera. Later we will watch this silent home movie.

There we are, in colored coats and hats and bright orange mittens. Suddenly my sister and I begin to run farther into the glen. The camera follows us for a while and then shifts to my dad, skipping behind, holding my mother’s purse, hamming it up for the camera. My mother must be laughing because the camera begins to shake wildly as it pans over the shadowed paths. It follows my father, who now pretends to be a monkey, jumping around the pine needles, stooped to the ground, picking at his hair, a perfect primate.

The camera shifts again to all of us waving, always waving, and silently the film ends, our hands suspended in midair.

While teaching, my dad is still writing Twilight Zone scripts and receiving potential scripts from other writers. He is also writing a screenplay adaptation of the best-selling novel Seven Days in May, by Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey II, about U.S. military leaders plotting to overthrow the president because he supports a nuclear disarmament treaty and they fear a Soviet sneak attack. The film, a political thriller directed by John Frankenheimer, just off another taut political thriller, The Manchurian Candidate, turns out to be a critical and popular success that very much captures the tensions of the times. Frankenheimer had asked my dad to write the screenplay, figuring their attitudes, interests, and styles would complement each other.

Since the beginning of his administration, President Kennedy had been criticized by the right wing for being soft on Communism and weak on defense. My father picks up on these issues in his portrayal of President Jordan Lyman. On a deeper level, the film displays several themes that are important to my father throughout his career. Prime among these is not succumbing to fear born of ignorance. In the nuclear age, he seems to be telling us, we can’t throw up our hands in helplessness over the enormity of the problem. With the stakes as dire as they are, we must all work positively to change things for the better. I think that is why he believes so firmly in the idea of the United Nations. As in Twilight Zone’s “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” my dad is warning us that the greatest threat we face is if a potential enemy uses our fears to get us to start destroying ourselves.

When my father flies back to LA to attend to other business, he also goes directly to the MGM studio to shoot several opening narrations for The Twilight Zone. Contrary to his plans to relax, he is under tremendous pressure during our time in Yellow Springs. Clearly, the six months there are not the respite he intends. And his attempts to revitalize, to reenergize, himself prove to be increasingly compromised.

But back then I know none of this. I only know when he walks down the stairs, his suitcase bumping against his leg, my father is leaving.

Had I looked closer, had I not been so young, would I have seen this? Could I have asked him to stay? Could I have slowed my father down?

When his teaching position ends and we are days away from going back to California, our rats have babies, tons of babies, hairless, pink, tiny things. In a mad rush my sister and I try to sell them and then try to give them away, but we are not successful. No one wants them. We have to leave a cage full of these baby rats with a friend whose parents agree to try to find them homes. By then, the rats have hair and are cute. (Well, cute for a rat.)

We leave in the spring of 1963. Leaning out of the car windows, on the way to the airport, we wave to our friends. We wave and wave, shouting “Good-bye, good-bye!” until we can barely see them. We drive farther away, picking up a little speed, and watch as they disappear entirely. Our hands fall to our laps, we stare straight ahead, and are quiet then.

Jeanne Marshall, a student who took my father’s writing class, remembers: “At our last seminar meeting in 1963, Rod cried while saying good-bye to all of us. He told us we would all be together again sometime, somewhere.”