CHAPTER FIVE

Embracing and Abandoning Bird Protection

CHAPMAN’S PARAKEETS

On a damp March morning in 1889, gunfire pierced the calm near the headwaters of Florida’s Sebastian River. By the time the ensuing confusion had quieted a few moments later, at least three Carolina parakeets (Cornuropsis carolinensis) lay dead within the lush, subtropical vegetation that bordered the meandering river. A fourth bird, only mildly wounded, was also captured by its assailants.

The four parakeets collected that day were remnants of a once vast North American population.1 The only species of the parrot family (Psittacidae) endemic to the United States (fig. 17), the bird originally ranged widely across the southeastern portion of the country. But over two hundred years of settlement had taken its toll. Deforestation had destroyed much of the moist habitat—typically mature sycamores and cypress trees growing on riverbanks and in swamps—the species required to live and reproduce. The parakeet also suffered relentless persecution at the hands of farmers, who feared that voracious flocks would destroy their valuable crops. By the late 1880s the few surviving Carolina parakeets were largely confined to the uninhabited regions of Florida. Although some ornithologists claimed that extensive populations remained in the unexplored regions of the state, most agreed with Charles E. Bendire’s gloomy assessment: “Civilization does not agree with these birds, and . . . nothing else than complete annihilation can be looked for. Like the Bison and the Passenger Pigeon, their days are numbered.”2

As if habitat destruction and persecution by farmers were not enough, the parakeet also came under attack as a result of the post-Civil War rage for collecting birds. Natural history collecting has always had a strongly aesthetic dimension.3 Not surprisingly, then, particularly showy species like the parakeet—with its brilliant plumage of green, yellow, red, and orange hues—were highly sought-after additions to the growing number of private and institutional bird collections begun in North America during the second half of the nineteenth century. And collectors of all kinds have always eagerly pursued rare or unusual examples of the objects they are amassing. Thus in a dangerous downward spiral repeated for a disturbing number of bird species, a decrease in the number of parakeets served to increase their value to collectors, whose predations further decreased the remaining population. Faced with the impending extinction of this and other species, the taxidermist William T. Hornaday’s urgent advice reflected the dominant ethos of the culture of collecting: “Now is the time to collect.”4

Figure 17. Audubon’s engraving of the Carolina parakeet. By the end of the nineteenth century bird collectors went to great lengths to obtain specimens of this increasingly rare (and now extinct) species. From the octavo edition of Audubon, Birds of America (1840-1844).

As the final stronghold of the Carolina parakeet, Florida became a mecca for naturalists seeking to capture the few surviving examples of this rapidly diminishing bird.5 Among those anxious to collect the rare species was the young ornithologist Frank M. Chapman. After two years of searching he had finally found his parakeets that March morning in 1889.6

The product of a wealthy family of bankers and lawyers, at age sixteen Chapman had graduated from Englewood Academy in New Jersey with little sense of what he wanted to do with his life.7 With no inclination to continue his education, he became a clerk at the American Exchange National Bank in New York City, an enterprise for which his father had once served as lawyer. A chance encounter with Fred J. Dixon, an ornithologist whom he met during his daily commute to the bank, sharply focused Chapman’s previously inchoate interest in nature, hunting, and the outdoors.8 Soon Chapman also met Clarence B. Riker, a young man his own age who had recently returned from a collecting expedition on the Amazon River.9 Riker, who had discovered a new bird species during his travels, enchanted Chapman with exotic tales of ornithological adventure. It was as if a whole new world had opened up to him.

Inspired by contact with these and other ornithologists, Chapman entered into his newfound hobby with a heretofore uncharacteristic intensity.10 In the spring of 1884 he volunteered to join the large network of observers gathering bird migration data for the AOU. Each of the six days per week he worked at the bank, Chapman rose before daybreak to observe and collect birds during the half-mile walk between his house and the West Englewood rail station. Whenever possible he spent additional hours in the field on his return trip in the evening. Although he had to be at the train station by 7:30 A.M. and he often remained at the bank until 6:00 P.M., Chapman averaged nearly two and a half hours in the field each workday that spring.

In the fall of 1886 the twenty-two-year-old Chapman stunned his “mystified colleagues” when he announced he was abandoning his promising banking career to pursue ornithology full-time.11 Less than two years later he received an offer to become Allen’s assistant at the American Museum of Natural History. The professionally conscious C. Hart Merriam chided Chapman for taking the position at the bargain rate of $50 per month: “Were it not that Mr. Allen needs you so very much, I should move to have you tarred and feathered for accepting at that price.”12 But as Chapman himself admitted, he came to the museum with “only a beginner’s knowledge of local birds and had everything to learn concerning the more technical side of ornithology.”13 Under Allen’s guiding hand, the American Museum proved to be the perfect environment to obtain that knowledge.

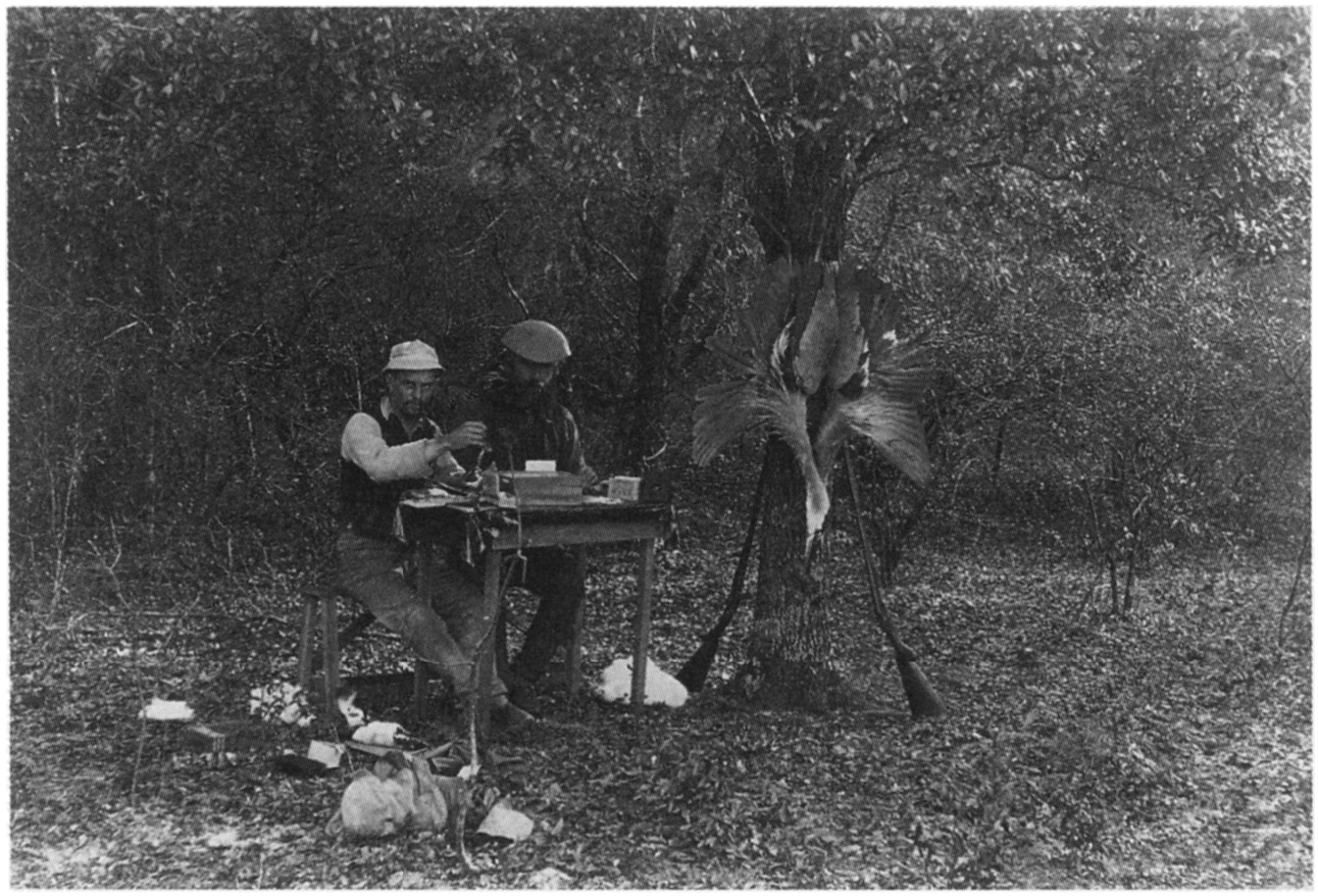

For several years Chapman arranged to continue his annual southern migration to collect specimens (fig. 18). In March 1889, while collecting birds and mammals in the Indian River region of Florida, he learned that Carolina parakeets had been spotted less than five miles from his base camp, a hunting lodge in Micco. Chapman and his guide, Jim, a nephew of the owners of the lodge, left early the next morning in hot pursuit of their quarry.

When they arrived near the headwaters of the Sebastian River later that afternoon, the two men immediately caught sight of the brilliant birds on the opposite bank. As he noted in his journal, this long-anticipated encounter with the parakeet thrilled Chapman: “You can imagine my excitement when he [Jim] called to me; I scampered for our guns and we immediately boarded the boat, pushed across and landed just in time to see seven Paroquets darting like lightening through the pines, twisting and turning in every direction. This was my first view of Cornurus in the state of nature, a sight I have long desired to feast my eyes on and which in imagination I have seen many times.”14

Figure 18. Frank Chapman and William Brewster preparing bird specimens in Florida, 1890. Florida was one of Chapman’s favorite collecting grounds.

A downpour the following morning temporarily extinguished hopes for finding the prized bird again but failed to dampen the two naturalists’ enthusiasm. The very next day, Chapman proudly proclaimed that despite “cloudy threatening skies” he had finally met with success: “It is all the same to me now, rain, hail, sleet, snow, anything, sun or no sun. [M]y mind is illumined by a serene joy which casts a radiance over the darkest landscape, for I have met Cornurus and he is mine, three adults and a young one.”15

Two days later Chapman and his guide encountered a second flock of parakeets. After securing five more specimens of the rare bird, Chapman was ecstatic. But his excitement soon turned to melancholy as the potentially grave consequences of his actions began to dawn on him. That night, after gathering the bodies of his cherished birds before him, Chapman noted in his journal:

I admired them to my heart’s content, counted them backwards and forwards[,] troubled over them generally, all the time almost doubting whether it was all true—for now we have nine specimens and I shall make no further attempt to secure others, for we have almost exterminated two of the three small flocks which occur here, and far be it from me to deal the final blows. Good luck to you poor doomed creatures, may you live to see many generations of your kind.16

Within two days Chapman’s resolve was put to a decisive test when he located what he believed to be the last flock of parakeets in the vicinity. Despite his stated intention to refrain from further molesting the bird, the overwhelming urge to possess the coveted species again triumphed. Using religious imagery that was later to pervade the bird protection movement, Chapman revealed his guilt over having collected additional specimens of the threatened species: “Good resolutions like many other things are much easier to plan than to practice. [T]he parakeets tempted me and I fell; they also fell, six more of them making our total fifteen.”17

Chapman’s determination to amass as many specimens of the parakeet as possible was hardly unusual. During the second half of the nineteenth century, scientific ornithologists occasionally acknowledged the importance of gathering life-history and behavioral data on birds, but the ornithological community as a whole focused almost exclusively on collecting. The parakeet itself provides compelling evidence for this general orientation. Over eight hundred specimens of Carolina parakeet skins, skeletons, and eggs gather dust today in museums around the world, yet scientists learned little concerning the life and behavior of this tragic species before the last known individual died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918.18

As his journal entries suggest, however, Chapman was not oblivious to the plight of the parakeet and other endangered species. During the next half-century that Chapman devoted to enlarging the American Museum’s ornithological collection, he was also a potent force in the bird protection movement. Long before the atomic age, the period most historians have identified as the beginning of an emerging social consciousness among scientists, Chapman and many other prominent ornithologists began acting on their own understanding of social responsibility.19 Chapman and his fellow scientists sincerely believed that their knowledge of the desperate predicament of birds carried with it the obligation to act: to educate the public, to lobby for appropriate legislation, and to do everything in their power—that is, everything short of banning collecting—to protect American bird life from the forces that threatened it. As founding editor of Bird-Lore (the official publication of the second Audubon movement) and lifetime board member of state and national Audubon societies, Chapman stood on the front lines of a remarkably successful national campaign to awaken American sympathy for the living bird.

Chapman’s life thus represents in a microcosm the larger tension that characterized scientific ornithology at the turn of the century. Chapman, like the ornithological community as a whole, sought to protect birds while asserting the absolute right to collect them for scientific purposes. It is this essential tension that I explore in the two chapters that follow. My focus is the bird protection committee of the AOU. The AOU served as a mouthpiece for the disciplinary and professional aspirations of scientific ornithologists, and its bird protection committee, created in 1884, provides a unique window onto that community’s attitudes toward collecting and protecting birds.

The American bird protection movement, which began in last two decades of the nineteenth century, was a broadly based reform coalition composed of humanitarians, preservationists, recreational hunters, scientists, and others. It was extraordinarily successful in raising public consciousness about the plight of native American birds, especially song birds. The common enemy that united the otherwise diverse elements within the movement was large-scale commercial hunting of birds for plumes and meat. Through a series of state and federal laws, an aggressive educational campaign, and the establishment of protective refuges, the movement reversed the population decline of many species.

However, ornithologists’ extensive involvement in bird protection efforts also had unanticipated consequences. The AOU bird protection committee played a central role in initiating and sustaining the American bird protection movement. But as that movement gained in size and independence, scientific ornithologists were forced to defend an increasingly yawning gap between the rhetoric of protection and the reality of current ornithological practice. In an effort to bridge this gap, scientific ornithologists attempted to redraw the traditional boundaries that had defined their practice. Commercial natural history and egg collecting—once considered integral parts of the edifice of ornithological science—were repudiated in an effort to silence criticism and thereby ensure the continued opportunity for “scientific” collecting.

DISCOVERING EXTINCTION

As historian Robert H. Welker has pointed out, the movement to protect birds in this country may have culminated in the actions of large, powerful groups at the end of the nineteenth century, but it began with “separate acts of protest by individuals.”20 While America marched westward under the banners of “progress,” “inexhaustible resources,” and “manifest destiny,” a few lone voices began to cry out for the countless creatures destroyed in the process.21 Naturalists, sport hunters, and explorers—men who had spent considerable time in the field and witnessed the effects of wildlife destruction firsthand—figured prominently among those early, isolated expressions of concern. As the nineteenth century wore on, these lone voices united into an anxious chorus echoing across the continent. For some Americans, progress had suddenly become a dual-edged sword.

By the middle decades of the nineteenth century, the rapid decline of two formerly abundant species, the buffalo (Bison bison) and the passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), forever shattered the myth of inexhaustiblity and helped ignite widespread discussion about the destruction of American wildlife.22 Both species elicited superlative descriptions from explorers and settlers who had encountered the prodigious numbers that once ranged across the North American continent. But in the decades following the Civil War, both suffered almost simultaneous population collapses as their habitat was destroyed by development and their numbers thinned at the hands of market hunters. There had been human-induced extinctions before the fall of the buffalo and the passenger pigeon, but these earlier episodes failed to elicit much concern about either the fallen species or the more general processes responsible for their demise. The rapid collapse of these two species served as haunting reminder that humans possessed the ability to forever alter the natural world and seemed to jar some Americans from their smug complacency.

The total extent of the passenger pigeon population that once inhabited North America will never be known with certainty, but it is likely that no other bird on the continent has ever approached the species in number.23 In one famous account from the early part of the nineteenth century, the ornithologist Alexander Wilson witnessed a continuous stream of migrating wild pigeons for over five and a half hours near Frankfort, Kentucky.24 Wilson calculated that over two billion birds darkened the sky above him that afternoon, an estimate consistent with descriptions at other locations until the middle decades of the nineteenth century.

Deforestation increasingly destroyed the breeding habitat of the passenger pigeon—the hardwood forests of the Northeast—forcing the remaining population westward. Alerted to the presence of their intended victims by an extensive network of telegraph lines, market hunters invaded vast nesting congregations, capturing and murdering prodigious numbers with nets, fires, and guns. The birds, both living and dead, were then shipped by rail to urban markets. What had been a gradual decline became precipitous in the 1870s, and by 1900 there were no more reliable sightings in the wild.25 The last passenger pigeon died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914.26

The buffalo barely escaped a similar fate, reaching a population size as low as one thousand or less before the initiation of successful efforts to bring the species back from the brink of extinction.27 Indians and bison had long coexisted on the North American continent, but the coming of the white man marked the beginning of the end for both. The large, gregarious beast provided an easy target for the waves of settlers who pushed the frontier line ever westward. But it was the arrival of the railroad in the middle decades of the century that assured the rapid destruction of the still robust bison population.28 The animal furnished nourishment for the hungry laborers who built the western railroad lines that knitted the nation together. More important for the future of the buffalo, the railroad provided a quick, inexpensive, and reliable means for bringing the hunters to their mobile quarry and for shipping hides and meat back to markets. At the same time, federal officials encouraged the brutal destruction, hoping to confine to reservations the resistant bands of Plains Indians who depended on the buffalo for food, clothing, and shelter.29

Although several commentators had suggested that the end of the buffalo was imminent, the young ornithologist and mammalogist J. A. Allen was among the first to do a detailed study of the decline.30 To regain his failing health and acquire western specimens for the Museum of Comparative Zoology, in April 1871 he and two assistants set off on a nine-month expedition to the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains. High on the list of specimens Allen hoped to secure was the buffalo. With the aid of railroads (which granted special rates for the party), professional hunters (who helped secure specimens), and U.S. Army officials (who provided a base of operations for the naturalists), the expedition proved a stunning success. Included among the thousands of specimens shipped back to Cambridge over the next nine months was an extensive series of buffalo skins, skeletons, and skulls procured near Fort Hays, Kansas.31

In 1876, almost five years after his return from the West, Allen published an exhaustive monograph, The American Bison, Living and Extinct. The first part of the study consisted of meticulous technical descriptions of the two extinct and one living species of North American buffalo. The second, longest, and final section of the monograph examined the former and present range of the sole surviving species of American bison. During the process of researching his monograph, Allen became convinced that this species was destined to endure the same fate as its long extinct cousins: “These facts are sufficient to show that the present decrease of the buffalo is extremely rapid, and indicates most clearly that the period of his extinction will soon be reached, unless some strong arm is interposed in his behalf.”32 In short, Allen became one of the first to recognize, document, and warn the public about the problem of anthropogenic extinction.

Not content to bury his alarming conclusions in an obscure academic tome, that same year Allen also published a series of five popular articles detailing the decline of the buffalo and other North American vertebrates. Allen’s first paper, “The North American Bison and Its Extermination,” summarized the results of his longer monograph and called the decline of the buffalo “one of the most remarkable instances of extermination recorded, or ever to be recorded, in the annals of zoology.”33 In a second article appearing six months later, Allen expanded his circle of concern to include other large indigenous mammals. While examining the literature on travel and exploration that had provided persuasive evidence of the decline of the bison, Allen also gleaned information on the former status of several other species. He soon discovered that a disturbing number of large mammals—like the moose, the gray wolf, the panther, the lynx, the black bear, the wolverine, the caribou, the elk, the Virginia deer, and others—had also suffered severe declines since the beginning of white settlement and that some might soon be facing the same fate that seemed to await the bison.

Although the specific story for each of these species varied, the broad outlines were similar. In their headlong rush westward, European settlers had transformed “hundreds of thousands of square miles of wilderness into ‘fruited fields,’ dotted with towns and cities, and intersected by a network of railways and telegraphs lines.”34 At every turn the “progress of the white race on this continent” had been marked by “reckless and wanton destruction of animal life.”35 During the nation’s centennial, when most Americans celebrated the taming of the landscape, Allen offered a somber counterpoint to the apotheosis of progress.

In this same pioneering series of articles Allen also highlighted the problem of bird destruction. A short notice in the American Naturalist called attention to the extermination of the great auk (Pinguinus impennis) at one of its last great colonial nesting sites, Funk Island in Newfoundland.36 According to one of Allen’s correspondents, these large, flightless birds had been abundant on the islands until mercilessly hunted down for their feathers in the 1830s and 1840s. Now no more remained there or anywhere else in the world.

In two longer articles Allen discussed the decline of several avian species in his native Massachusetts and the eastern United States more broadly. Again, early descriptions of abundance provided a baseline against which to measure current population levels. According to Allen, at least four birds—the great auk, the wild turkey, the sandhill crane, and the whooping crane—had become wholly exterminated within the boundaries of Massachusetts since the beginning of European settlement.37 A great many others, including the pileated woodpecker, the passenger pigeon, the heath hen, the American swan, most of the wading and swimming birds, and nearly all the rapacious species had also suffered marked declines. Allen’s more general account of the decline of birds in the United States suggested that at least one other bird, the Carolina parakeet, was also in grave danger.38

These drastic changes in bird life had not passed entirely unnoticed. Allen pointed out that several states and territories had enacted laws to protect “beneficial birds”: game birds and those nongame species thought to prey on, and thereby keep in check, the noxious insect populations that destroyed crops. But these laws had thus far been generally ineffective and rarely enforced. Allen concluded the last of this prescient series with a variation on his now familiar theme: “Unless something is done to awaken public opinion in this direction and to enlist the sympathies of the people in behalf of our persecuted birds, the close of the next half-century will witness a large increase in the list of wholly exterminated species.”39

Allen looked to two existing communities, sport hunters and humanitarians, as possible advocates for the birds. As historians John Reiger and James B. Trefethen have emphasized, recreational hunters were among the first to decry the large-scale, commercial exploitation of wildlife, and they have remained active in conservation causes up to the present.40 Beginning as early as the colonial period, the local extermination of game species had occasionally led to the creation of protective laws.41 But it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that those who hunted for sport began to demand more stringent regulations to protect their would-be targets. Hunting clubs, game protective associations, and related organizations proliferated beginning in the 1840s. By the 1870s a series of national weeklies—which included coverage of hunting, fishing, conservation, and natural history—helped foster a sense of shared national identity for the sporting community.42 Informed by an ethos of “fair chase” and anxious to maintain a continued supply of game well into the future, recreational hunters provided a politically powerful voice for wildlife protection. Allen recognized the effectiveness of sport hunting organizations in limiting “the destruction of game and fish species,” but he was skeptical about their willingness to fight vigorously for nongame species, especially small songbirds, which did not appeal “so strongly to their self-interest.”43

Besides sport hunters, Allen hoped that “associations for the ‘Prevention of Cruelty to Animals’ ” might also contribute to the cause of bird protection. Unlike hunters, who were largely informed by self-interest and utilitarian motives, humanitarians were moved by a distaste for animal pain and suffering. The humane movement was an extension of the Darwinian revolution, which helped bridge the gap between humans and the beasts, and it came at the heels of the development of effective anesthetics, which first suggested the possibility of a world without pain.44 Henry Bergh, a wealthy young New Yorker with little previous sense of direction, discovered the cause in England during his grand tour in the 1860s. He returned home in 1866 to create the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, which, despite its name, largely confined its activities to the state of New York. Over the next two decades animal lovers organized dozens of state humane societies. Initially humanitarians focused on alleviating suffering in domestic animals, but they also regularly expressed concern about the plight of wildlife.

In his 1876 essay on bird destruction, Allen failed to mention a third strand of conservation that was also to be crucial in the fight to preserve wildlife from the continuing onslaught of civilization: the nature appreciation movement. Though this movement lacked the clear institutional manifestations of the sport hunting and humanitarian movements, it was nonetheless an increasingly potent force in defense of the American landscape. As mentioned earlier, nature appreciation in this country had its roots in the Romanticism and Transcendentalism of the early to mid-nineteenth century.45 As the century wore on, it continued to reemerge under a variety of guises.46 For some, periodic retreats into the relative wilderness of state and national parks offered a temporary antidote to the ills of an increasingly urban and industrial nation. But most Americans lacked the desire to retreat permanently from civilization. Rather, they sought a more secure middle ground between the extremes of nature and civilization: the urban park or cemetery, the borderland suburbs, and the country club. Whatever form nature appreciation took, one thing was clear: the more Americans removed themselves from nature, the more they came to value it.

Allen concluded his final article with a call for the formation of an entirely new organization, special “societies. . . whose express object should be the protection throughout the country of not only . . . innocent and pleasure-giving species, but also the totally innocuous herons, terns, and gulls, whose extermination is progressing with needless and fearful rapidity.”47 Although it would be over a decade before anyone would take up his suggestion, Allen’s remarkable series of papers first alerted Americans to the specter of human-induced extinction.

EMBRACING BIRD PROTECTION

Bird protection was not among the principal items on the agenda of the technically oriented scientists who organized the AOU in 1883. However, it did come up as early as the second meeting of the union in October 1884, when William Brewster called attention to the “wholesale slaughter of birds, particularly Terns, along our coast for millinery purposes.” Following Brewster’s motion, the AOU voted to create a six-member “committee for the Protection of North American Birds and eggs against wanton and indiscriminate destruction.”48 At the request of J. A. Allen, president of the AOU, Brewster reluctantly agreed to serve as chair for the new committee, but he promptly resigned three months later, citing a lack of time, difficulties with his eyesight, and inability to attend the next AOU meeting as reasons for his withdrawal.49 In the hope of finding someone willing to serve as chair, Allen then approached other members of the committee, including George Bird Grinnell, editor and part-owner of the sporting and natural history periodical Forest and Stream. Grinnell rejected Allen’s offer but indicated that he strongly supported the work of the committee and had long contemplated a plan to use his magazine as a vehicle to promote bird protection.50 A year later Grinnell launched the first Audubon Society through the pages of Forest and Stream.

When the issue of what to do with the bird protection committee again came up during the next meeting of the AOU in the fall of 1885, Brewster urged that the committee be continued with a chair who could “give the matter the attention and time its high importance demanded.” C. Hart Merriam argued that work of the committee was “the most urgent before the Union.”51 Others in attendance agreed, but the issue of who would chair the committee remained unresolved when the annual meeting adjourned the next day.

The committee was finally roused into action two months later, at a meeting in New York on the afternoon of 12 December 1885.52 Full of “new life and energy,” the committee voted to increase its size from six to ten members and elected the oil-machinery manufacturer George B. Sennett as its chair.53 Sennett’s election marked the beginning of an intense period of activity for the bird protection committee. With seven members of the expanded committee residing in the vicinity of New York City, the ambitious new chair scheduled a series of over twenty regular Saturday afternoon meetings.54 After discussing how it might carry out its charge most effectively, the committee decided to concentrate on educating the public regarding the scope and consequences of the bird destruction problem.55

Toward this end, the new committee began gathering information for the publication of a bird protection bulletin. As early as 1 December, almost two weeks before the first meeting of the reorganized committee, the editor of Science had offered his journal as a forum to “come to the aid of our native birds.”56 After gathering material for the next two months, the committee published a sixteen-page supplement to Science. With the aid of G. E. Gordon, president of the American Humane Association, the committee distributed over one hundred thousand additional copies of its manifesto.57

The first AOU bulletin introduced many arguments that were to become standards within the bird protection movement. The introductory, longest, and most important essay was authored by none other than J. A. Allen. Echoing his earlier warning, he insisted that without immediate action, “many species, and even genera” of North American birds appeared to be heading for the same fate as the rapidly diminishing American bison. What became a standard litany of specific threats followed this general cry of alarm. Commercial game hunting, egging for the restaurant trade, egg collecting by boys, and indiscriminate shooting by “sportsmen,” immigrants, and “colored people” were each briefly discussed and uniformly condemned.58 But the principle target of Allen’s wrath was the millinery trade, a force that remained the nemesis of the bird protection movement for over three decades.

Although feathers had long been used to decorate hats, it was not until the end of the nineteenth century, when fashion-conscious middle-class women adopted the practice, that it represented a serious threat to bird populations.59 Mass circulation magazines, like the Delineator, Harpers Bazar, Argosy, and Vogue, fueled the craze for the latest fashions coming out of New York, London, and Paris. Millinery designers turned to bird feathers for something eye-catching to decorate their wares. And feminine fashion mavens gobbled up the procession of ever-changing styles. As Allen admitted, determining the precise level of destruction was frustratingly difficult, but a stroll down any American street revealed that the habit of trimming hats with feathers was pervasive: “We see on every hand—in shop window, on the street, in the cars, and everywhere women are seen—evidence of its enormous extent.”60 According to Allen, the new feather fad represented a threat to North American birds “many times exceeding all the others together.”61

Allen recognized that in condemning the “wholesale destruction of birds,” he was potentially exposing ornithologists to criticism for engaging in what might seem like equally voracious collecting practices. The issue had first been raised three months earlier when the nature writer John Burroughs labeled ornithological collectors, the “men who plunder nests and murder their owners,” as “among the worst enemies of our birds.”62 After recounting several examples of what he considered excessive collecting gleaned from the pages of natural history journals, Burroughs concluded with a clear indictment of scientific ornithology:

Thus are the birds hunted and cut off, and all in the name of science; as if science had not long ago finished with these birds. She has weighed and measured and dissected and described them and their nests and eggs, and placed them in her cabinet, and the interest of science and humanity now is that the wholesale nest-robbing cease. I can pardon the man who wishes to make a collection for his own private use, though he will find it less satisfactory and valuable than he imagines; but he needs but one bird and one egg of a kind; but the professional nest robber and skin-collector should be put down, either by legislation or with dogs.63

Although Burroughs found large-scale commercial and “scientific” collecting deplorable, he did not oppose collecting under all circumstances. His first book, Wake-Robin (1871), urged novice bird students not to be squeamish about resorting to the collecting gun: “First you find your bird; observe its ways, its song, its call, its flights, its haunts; then shoot it (not ogle it with a glass), and compare with Audubon. In this way the feathered kingdom will soon be conquered.”64 But according to Burroughs, once having “mastered the birds” in this manner, the “true ornithologist leaves his gun at home.”65 He had little patience for the “closet” ornithologist, the museum worker who rarely ventured to the fields and forests and apparently lacked interest in the lives of the birds he was naming, describing, and classifying: “He is about the most wearisome and profitless creature in existence. With his piles of skins, his cases of eggs, his laborious feather-splitting, and his outlandish nomenclature, he is not only the enemy of birds, but the enemy of all who would know them rightly.”66

Had Burroughs been unknown, his critique might have been safely ignored. But Burroughs was a widely read nature writer whose popular essays often centered on birds. In the eyes of the public, he was an authoritative ornithologist. Therefore, his harsh words demanded a response.67 As was often the case, it was J. A. Allen who took up the cudgels for scientific ornithology. In a short, vituperative reply, Allen accused Burroughs’s essay of being “grossly erroneous in statement” and “slanderous in spirit.”68 He continued on the offensive by pointing out that Burroughs had failed even to mention the most potent threat against birds: “wholesale slaughter of birds for millinery purposes.” According to Allen, the total destruction of birds for “scientific or quasi-scientific purposes is ‘but a drop in the bucket,’ ” when compared to that of the millinery trade.69

In the bird protection committee bulletin, Allen expanded upon his earlier defense of scientific collecting. His argument of scale soon became a standard within the community of scientific ornithologists.70 After estimating the total number of specimens in museums and private collections in this country to be at most five hundred thousand and the number of birds annually slaughtered for millinery purposes to be at least five million, Allen concluded that the millinery trade offered a far graver threat to American bird life than did scientific collectors. When the large number of years it took to bring together existing ornithological collections was considered, Allen argued that plume hunters took a toll “a thousand times greater than the annual destruction of birds (including also eggs) for scientific purposes.”71

Of course, there were difficulties with Allen’s argument. First was the perennial problem of gathering accurate statistics both on the level of ornithological collecting and on the number of birds killed by the millinery trade. More importantly, even if the often repeated argument of scale was an accurate description of the relative impact of ornithologists and milliners on overall bird populations, it failed to recognize that ornithologists went to great lengths to take rare birds—as Chapman had done with the parakeet in Florida (fig. 19)—and hence could have a devastating effect on local populations of threatened species.72

A publication that appeared soon after the first bird protection bulletin shows why ardent protectionists might question the collecting practices of scientific ornithology. In a three-part article for Auk, former Agassiz student and Nuttall Club member W. E. D. Scott called attention to the severe population decline in several rookeries on Florida’s west coast.73 During a five-week reconnaissance trip in the spring of 1886, Scott had visited a number of nesting and roosting sites. Six years previously he had seen countless herons, egrets, pelicans, ibises, gulls, terns, and other water birds at these sites, but now they were virtually barren. The culprits, Scott argued, were commercial plume hunters, local men who made a handsome income selling bird skins and plumes for anywhere from ten cents to a dollar each to taxidermists and other northern buyers. Scott was unable to catch up with the most notorious plume buyer, Alfred Lechevalier, but he did interview the taxidermist Joseph H. Batty of New York City, who had “not less than sixty men . .. working on the Gulf Coast” that season.74

Figure 19. William Brewster with an ivory-billed woodpecker, 1890. Frank Chapman found this specimen during an expedition along the Suwannee River in Florida.

Yet Scott saw no inconsistency in decrying commercial hunting as a “great and growing evil” and on the same page noting glibly that he had collected “about two hundred and fifty birds” during this single trip, including a series of sixty examples of a single subspecies of the sandwich tern, Sterna sandvicensis acuflavida. What now seems even more remarkable is that less than two weeks after Scott wrote Allen of his desire to publish his account of bird destruction in Florida so he could “let the public get an idea of the magnitude of the slaughter and try to do something to stop the cruelty,” he was asking “How much can the museum afford to spend in buying first plumages and series of the herons of this region? I have a large lot that are very interesting.”75 Two years later Scott had nearly three thousand Florida specimens he was trying to sell, including a series of seventeen of the rare Bachman’s warbler ( Vermivora bachmanii)!76

Continuing the series of apparent contradictions surrounding the episode, Joseph H. Batty, once vilified in the pages of the Auk as a despicable plume hunter, was later lionized as a martyr of science.77 It seems that in an era of increasing state and federal legislation suppressing commercial hunting, Batty had “reformed his ways.” He had abandoned plume hunting to become a collector for the American Museum of Natural History, which paid him to send as many birds and mammals as possible back to its expanding collections. Scott and Batty reveal the ways in which the lines between scientists, professional collectors, and taxidermists remained fluid well into the latter decades of the nineteenth century. It is no wonder, then, that some ardent protectionists began to claim that killing birds, whether in the name of science or of fashion, was equally reprehensible.78

Following his brief survey of the threats that plagued North American birds, Allen turned to the crucial question of why the problem should concern the average citizen. After all, trade in decorative nongame birds provided income for numerous plume-hunters, taxidermists, manufacturers, and others involved in the millinery trade. Was not the obvious economic benefit derived from the sale of these otherwise valueless birds justification enough for the practice? Using aesthetic and utilitarian arguments that remained central to the bird protection movement for decades, Allen attempted to counter the still-dominant belief that nature was little more than a storehouse of potential resources waiting to be discovered, extracted, and sold.

Birds, Allen proclaimed, possess an “aesthetic value” which, though not readily renderable into the language of dollars and cents, was nonetheless real and important:

Birds, considered aesthetically, are among the most graceful in movement and form, and the most beautiful and attractive in coloration, of nature’s many gifts to man. Add to this their vivacity, their melodious voices and unceasing activity,—charms shared in only [a] small degree by any other forms of life,—and can we well say that we are prepared to see them exterminated in behalf of fashion, or to gratify a depraved taste?79

For Allen and others who advanced the aesthetic argument, a country without songbirds was like “a garden without flowers, childhood without laughter, an orchard without blossoms, a sky without color, [and] roses without perfume.”80

For those who remained unmoved by Allen’s appeal to the intrinsic beauty of the living bird, he offered a more practical defense of bird protection: “The great mass of our smaller birds, numbering hundreds of species, are the natural checks upon undue multiplication of insect pests.”81 Here Allen was resorting to essentially the same argument that economic ornithologists had been making for years. Working under the long-held assumption that nature remains in overall balance, they moved from a limited knowledge of the diets of birds to the conclusion that they were a primary agent in halting the potentially explosive growth of insect pest populations.82 Although the field of economic ornithology was still in its infancy at the time he was writing, Allen was confident that investigations undertaken by the Department of Agriculture’s recently created Division of Economic Ornithology and Mammalogy would merely provide finer detail for an outline that was already clearly in place.83

The bird protection committee conceived its primary mission to be one of alerting the public to the problem of bird destruction, but it also recognized the need for effective legislation to complement its educational efforts. The first bird protection bulletin contained a call for uniform state legislation to protect the songbirds and other nongame birds that had been largely ignored by sport hunters. The committee’s suggested legislation became known as the AOU model law.84 Prominent among the provisions of the proposed law—which made it illegal for anyone to kill, purchase, or sell any nongame bird, its nest, or eggs—was a section authorizing local natural history societies to grant permits for “scientific” collecting to anyone over the age of eighteen who could produce the required license fee ($1.00), a properly executed bond, and an affidavit signed by two recognized ornithologists.85 From the time of its first publication, the permit clause—with its demand to differentiate legitimate scientific collecting from other forms of bird slaughter—became a source of tension between scientific ornithologists and the collectors, taxidermists, and natural history dealers who had once been closely allied with them.

GRINNELL’S AUDUBON SOCIETY

While the bird protection committee was preparing to publish its first bulletin, a second, closely related force for bird protection was established. The first Audubon Society was the brainchild of George Bird Grinnell, scientist, sportsman, patrician, and longtime publisher of Forest and Stream.86 After receiving his A.B. from Yale in 1870, Grinnell became part of an army of students collecting western fossils for the paleontologist O. C. Marsh. Forced to abandon his family-owned New York investment business following the panic of 1873, Grinnell took a position as Marsh’s assistant at the Peabody Museum in New Haven. The next summer he joined an expedition with General George Armstrong Custer, who had brought several scientists along with his troops in an attempt to disguise what was in reality a military mission in the Black Hills of the Dakota Territories. Custer invited Grinnell to join him again on his more famous and fateful campaign of 1876, but he declined in order to continue his studies in New Haven.

At almost the same time that J. A. Allen was writing his remarkable series of articles on the decline of North American mammals and birds, Grinnell was independently reaching a similar conclusion. As was often the case, witnessing the level of wildlife destruction in the West proved a revelation for Grinnell. In 1875 he accompanied William Ludlow on an exploration of Yellowstone National Park, which had been created only three years previously. As Grinnell announced in the letter that accompanied his report, the experience had convinced him that “the large game still so abundant in some localities will ere long be exterminated.”87

By the time he received his doctorate from Yale in 1880, Grinnell and his father had gained a controlling interest in Charles Hallock’s sporting and natural history periodical, Forest and Stream. Grinnell, who had served as natural history editor of the publication since 1876, became editor-in-chief, a position he was to hold for thirty-five years. Under Grinnell’s guiding hand, the periodical consolidated its position as a leading voice in condemning the commercial exploitation of wildlife.

Soon after taking over Forest and Stream, Grinnell became involved with the AOU and its bird protection efforts. As a well-known naturalist and man of means, he was a logical choice to be invited to the organizational meeting of the AOU in 1883.88 That same year he published the first in a series of letters and editorials condemning the destruction of songbirds at the hands of the millinery trade.89 Convinced of the urgency of the problem, Grinnell agreed to serve as a member of the original AOU bird protection committee created in October 1884 but declined an offer to chair the committee when Brewster resigned three months later. As he indicated to Allen, he strongly supported the committee’s mission but was too busy with his own bird protection initiative.90

On 11 February 1886, less than two weeks before the AOU bird protection committee issued its first bulletin, Grinnell published an editorial proposing the formation of an “Audubon Society” dedicated to the “protection of wild birds and their eggs.”91 The new organization was named after America’s most famous artist-naturalist, John James Audubon, whose striking, anthropomorphic bird portraits had inspired many to see the creatures around them in a new, more sympathetic way. Although Audubon was capable of what now seems like excessive slaughter of wildlife, he was also among the first to notice and lament the decline of several species. Grinnell’s decision was also influenced by his boyhood memories of Audubon Park, just north of Manhattan, where he had lived and attended a small school run by Audubon’s widow, Lucy.

The basic plan of Grinnell’s Audubon Society was straightforward. Membership was free and open to anyone who pledged to “prevent as far as possible, (1) the killing of any wild birds not used for food; (2) the destruction of nests or eggs of any wild birds; and (3) the wearing of feathers as ornaments or trimming for dress.”92 The national society was to be organized into local chapters, to which Grinnell promised to send “without charge, circulars and printed information for distribution.” Grinnell was careful to stress that the work of the new society was not to replace, but to be “auxiliary to that undertaken by the Committee of the American Ornithologists’ Union.”93 It was to be the popular arm of the bird protection movement. With backing from a number of prominent leaders and supporters of the humane movement—including Henry Ward Beecher, John G. Whittier, John Burroughs, George T. Angell, Henry Bergh, and G. E. Gordon—the first Audubon Society’s membership rolls quickly mounted.

One of the first of the many local chapters of the Audubon Society was organized at the all-female Smith College in Massachusetts. Just over a month after Grinnell issued his call, Fannie Hardy and Florence Merriam, both members of families that included prominent naturalists, created the Smith College Audubon Society.94 Shortly after launching their new society, Hardy wrote to Brewster informing him of their progress and asking him to address the “enthusiastic” but “lamentably ignorant” group. Hardy also detailed the members’ efforts at self-education:

One girl who has stripped all the feathers from her hats, is now trying to hire small boys to kill her birds to skin,—all in the interests of science of course, and I, remembering that I was a taxidermist before I was a bird defender, I am helping her on in it. Half a dozen more are only waiting until they can get some birds to work. But these are all of the biology class and don’t mind about killing things. The rest are much more tender-hearted and think Nature is a goddess and Thoreau is the prophet of Nature.95

Early in May, Merriam arranged for Burroughs to lead the new society on a series of bird walks. As Merriam later noted, under his enchanting spell, “we all caught the contagion of the woods.” Following Burroughs’s visit, a hundred young women, nearly a third of the student body, renounced the wearing of feathers and joined the new group.

Figure 20. Cover of Audubon Magazine, 1887. George Bird Grinnell began publishing this short-lived periodical in a failed attempt to generate revenue for his equally ephemeral Audubon Society.

The success of the movement as a whole mirrored that of the chapter at Smith College. By the end of 1886 the Audubon Society boasted over three hundred local chapters and nearly eighteen thousand members.96 Early the next year Grinnell introduced Audubon Magazine (fig. 20) to “give stability to the Society, foster the zeal of the thousands now on its rolls, increase the membership, aid in carrying out the Society’s special work, and broaden the sphere of effort.”97 Beyond these lofty aims, he also hoped that income derived from the sale of the new magazine, which cost subscribers fifty cents per year, would alleviate the increasing financial burden posed by the growing society. The pages of Audubon Magazine featured news of the Audubon Society, popular articles on birds, children’s stories, biographical sketches of Audubon and Wilson, and regular appeals like Celia Thaxter’s call to the “tender and compassionate heart of the woman” to look upon the wearing of birds "as a sign of heartlessness and a mark of ignominy and reproach.”98

CRITICS OF CONSERVATION

The appearance of the widely circulated AOU bird protection bulletin and the launching of Grinnell’s Audubon Society awakened a nationwide discussion of the problem of bird destruction. American newspapers and periodicals were generally sympathetic to the protectionists’ message, but from the start there was also opposition. Not surprisingly, the main targets of the bird protection movement— the milliners, who also had the most to lose by its success—were among the first to challenge protectionists’ claims. Opposition also came from less likely sources: scientists, collectors, and taxidermists. During its brief period of activity in the mid-1880s, the AOU bird protection committee was repeatedly forced to defend its claims about the causes of and appropriate remedies for the problem of bird destruction.

Frank W. Langdon, a physician from Cincinnati, Ohio, who had been invited to help found the AOU three years earlier, was one of the few scientific ornithologists to challenge the bird protection committee publicly.99 In a speech delivered before the Cincinatti Natural History Society in the spring of 1886, Langdon not only sought to discredit many of the statistics found in the committee’s first bulletin, but also disputed the very premise of bird population decline upon which the bulletin had been based. Coming from a recognized expert on local birds, Langdon’s widely publicized critique threatened not only to undermine the authority of the new committee, but also to stifle the organizing efforts of Grinnell’s Audubon Society.100

Again it was J. A. Allen’s acerbic pen that came to the rescue. After a short summary of the recent achievements of the bird protection movement, Allen claimed that "the only discordant notes heard from any quarters were the subdued mutterings of a few reprehensible taxidermists, caterers of the milliners, whose pockets were affected by the movement in favor of birds,” and Langdon, an “ornithologist of some supposed standing as a man of sense and culture.”101 Unleashing all his stops, Allen called Langdon’s arguments “palpably absurd,” “perniciously misleading,” and full of “false premises, misstatements, and misrepresentations.” He refused to provide a detailed refutation—to do so might have granted his critique greater legitimacy—but he did point out that the Cincinnati Society of Natural History had nearly unanimously passed a resolution supporting the work of the AOU bird protection committee. The lone dissenting vote came from Langdon.

In the end what most divided Langdon and the bird protection committee was a divergent set of assumptions. Bird protectionists had begun, however tentatively, to question the right of humans to exploit nature without regard to the consequences. On the other hand, Langdon was a strong advocate of the more pervasive belief that it was “a well-established right of man to use all natural objects for the furtherance of his necessities, his convenience, or his pleasures.”102 For many in the generation of naturalists that came of age when the buffalo and the passenger pigeon teetered on the brink of extinction, this was no longer a tenable position.

A more serious and recurrent challenge to the work of the bird protection committee came at the next annual meeting of the AOU in November 1886. A letter from a disgruntled taxidermist who “complained bitterly” about the bird protection law that had recently passed in New York resulted in a lengthy discussion on the relationship between scientific ornithologists and taxidermists.103 There to present the concerns of taxidermists was Frederic S. Webster, a former employee of Ward’s Natural Science Establishment and a founder of the Society of American Taxidermists who maintained a private studio in Washington.104

At the 1886 AOU meeting, Webster expressed deep regret concerning “the attitude of ornithologists toward taxidermists, which seemed to be one of enmity rather than friendship.” The source of his apprehension was the work of the bird protection committee, the newly launched Audubon movement, and more particularly the AOU model law, which, by allowing collecting of protected birds only “for strictly scientific purposes,” threatened “to prevent work in legitimate taxidermy.” Narrowly interpreted, the new law would remove an important source of income for private taxidermists, who had long offered stuffed bird specimens not only for museums and private cabinets, but also for decorating store windows and parlors.

William Brewster tried to reassure Webster, and all taxidermists, that scientific ornithologists were not out to destroy their business. Brewster had relied heavily on professional collectors and taxidermists to build up one of the largest private collections in the nation.105 And he fought for their interests during the deliberations of the bird protection committee that led up to the first bulletin. At one point he warned that if the requirements for obtaining collecting permits were too strict, they would “sound the death knell for professional taxidermists and scientific collectors, who earn their living by selling birds. I consider such prohibition unjust, unwise, and uncalled for. Neither museums nor private collectors can dispense with professional taxidermists. Many of the latter are honorable men, and warmly interested in the protection of birds and the suppression of millinery collection.”106

At the annual AOU meeting Brewster again came to the defense of taxidermists by pointing out that they “were respected by ornithologists, who looked upon them as efficient and indispensible allies.” The bird protection committee supported granting permits to “honest taxidermists”; it only wanted to prevent the “abuse of the privilege of collecting” represented by “wholesale traffic in birds for commercial purposes by men who had no claim to be ranked as taxidermists.”107 Allen further clarified Brewster’s sentiments by claiming that the AOU model law was not intended “to cripple legitimate taxidermy, but mainly and primarily to prevent destruction of birds for millinery purposes.”108 Despite these assurances, taxidermists justifiably remained skeptical. They were not the only ones who were concerned about the AOU’s stand on collecting.

PERMIT PERTURBATIONS

The Ornithologist and Oologist had already been at odds with the AOU over its exclusive membership policy and its advocacy of trinomial nomenclature. Now, under the ownership of the natural history dealer Frank B. Webster (no relation to Frederic S. Webster), the magazine also became the central battleground between scientific ornithologists and the larger community of collectors, taxidermists, and dealers who felt excluded by the new AOU law.

The initial exchange was prompted by the numerous complaints of large-scale bird destruction at the hands of millinery interests that began appearing in Forest and Stream in 1883. An editorial in the June 1884 issue of the Ornithologist and Oologist responded with the claim that “the grievance is purely sentimental” and asserted that “birds of prey are far more destructive than either collectors or professional taxidermists.”109 AOU member Frederic A. Lucas, another former Ward employee now at the U. S. National Museum, responded with the standard economic argument: more than sentiment was at stake, for birds were responsible for keeping insect populations in check. He also flatly asserted that humans destroyed far more songbirds and insectivorous birds than birds of prey.110

At this point, the exchange became characterized by escalating levels of invective. In a response more sarcastic than sincere, the longtime Boston taxidermist W. W. Castle mocked Lucas for presuming that the public would accept his assertions about the level and causes of bird population declines simply because he was an employee of the U. S. National Museum. He also called for more specific statistics regarding the number and kinds of birds killed for millinery purposes.111 Lucas temporarily bowed out of the argument at this point, but his friend L. M. McCormick continued to push the position that “only a small proportion of the birds sacrificed in the name of science and taxidermy are legitimately used.”112 In McCormick’s view, millinery interests and overzealous collecting were playing havoc with the birds. After McCormick cited a series of examples in which systematic bird destruction had been followed by insect irruptions, Castle responded that his opponent had not provided “one scintilla of evidence” that songbirds and insectivorous birds were declining and that if they were, it was due to commercial hunting.113 Following replies by Lucas and McCormick, the issue dropped from the pages of the Ornithologists and Oologist, only to return with a vengeance a year later.114

The publication of the AOU law and its quick passage in New York transformed the debate between scientific ornithologists and other bird collectors. The argument had previously turned on whether there was an actual decline in bird populations and to what extent commercial collectors, especially millinery collectors, were responsible. Now both sides accepted the premise of population decline and both pinned the primary blame on the milliners.115 The point of contention shifted to the AOU model law, with its call for the elimination of nongame bird hunting except for “strictly scientific purposes” and especially the permit system. The recurring fear expressed in the pages of the Ornithologist and Oologist was that implementation of the permit system would necessarily result in the suppression of collecting by all amateurs, taxidermists, and dealers.

The opening volley came only a month after the appearance of the AOU model law, when C. H. Freeman urged that it would be “unwise to rigidly exclude all amateur students in ornithology from collecting specimens.” Freeman appealed to the egalitarian sentiments of his audience to support his argument for a broad interpretation of who should be authorized to collect:

It is rather harrowing ... to the amateur who devotes only a portion of his leisure time to his favorite science, to be debarred from further investigations through the influence of men who in their association “organ” [the Auk] relate the comparison of specimens from their collection, with a cabinet of over ten thousand, with specimens from some equally overstocked cabinet of another “scientist.” No. Such laws will not work, our Republic affords equal liberties to every one, provided the principles and intentions are alike, regardless of associations or pecuniary worth.116

A steady stream of editorials and letters challenging the AOU and its bird protection activities soon followed. Frederic H. Carpenter, whom Webster had recently hired as editor of the Ornithologist and Oologist, applauded attempts to eliminate bird destruction at the hands of milliners but decried the “tendency among associated [AOU] scientists to arrange themselves in opposition against the amateur and the taxidermists.” Carpenter then attempted to show that taxidermists were “no more destructive” than ornithologists by comparing the number of birds collected by “eight prominent scientists” (48,340) with those handled over a roughly equal period by “ten taxidermists” (37,480). In the same editorial Carpenter also came to the defense of the “amateur student of bird-life”: “When the love of nature draws one forth in pursuit of a congenial and profitable study of our birds, we are of the opinion that it should be as allowable by law as any exploration published in our scientific journals.” In his experience, Carpenter argued, the “arrangement and records” of the bird collections amassed by “unknown workers in ornithology . . . compare most favorably with those of the scientist.”117 As revealed in a follow-up editorial the next month, Carpenter felt taxidermists had been betrayed by scientific ornithologists’ refusal to defend their collecting prerogatives:

In this dilemma they [taxidermists] are deserted by the class of men who should, from a sense of justice, have firmly stood by them. We refer to certain of the professional ornithologists, many of whom have employed these taxidermists to collect for them. If we interpret the law aright, the principal is held responsible with the agent; but these associated “scientists,” when asked to give the reason for the “scarcity of birds” will with Pharisaical air, point the scornful finger at the taxidermist.118

The attack continued in the next issue of the Ornithologist and Oologist, with W. DeForrest Northrup decrying the way in which the issue of bird protection had split the previously cohesive ornithological community. In pushing for the permit clause, members of the AOU had ignored “the privileges of the young ornithologist.” They had also refused to come to his defense when protectionists accused the amateur of excessive destruction of birds. Northrup hinted that if the facts were known, scientific ornithologists might soon have to answer similar charges: “What is the history of the Swainson’s warbler in South Carolina and the prominent ornithologist [William Brewster] connected with their slaughter, who himself or by proxy secured all that could be found? But never mind, he is one of the committee for the protection of American birds.”119

Scientific ornithologists could no longer stand to remain silent. Disturbed by Northrup’s attack on his character, Brewster wrote to Allen to complain. Allen replied that the recent flurry of abuse directed at the bird protection committee was “an attempt to crystalize the antagonism of the taxidermist and unprincipled collector into an organized opposition to the movement in behalf of the birds” and “to foster ill-feeling on the part of ‘amateurs’ against ‘high science’ and scientific ornithologists.”120 Uncertain how to respond, he had written the longtime champion of the amateurs and AOU Councilor Montague Chamberlain to suggest that he reply.

Chamberlain accepted Alien’s challenge. His initial rebuttal protested that in publishing the recent attacks on the AOU and its bird protection committee, the Ornithologist and Oologist had become a “vehicle for misrepresentation and injustice.” Far from discouraging the work of young students, the AOU had sought to offer “all possible assistance in their studies.” Scientific ornithologists recognized that “from the ranks of amateurs today must come the scientists of the future,” and therefore the permit provisions of the AOU model law had placed amateurs “on the same footing as professional scientists.”121

Chamberlain’s letter generated two immediate responses. An anonymous correspondent asserted that whether the AOU bird protection committee originally had intended it, the permit system resulted in the suppression of amateur students in the East.122 In a letter the next month Northrup again accused the AOU of trying to control who did and did not get permits by requiring that all applications be endorsed by “some scientific gentlemen” (i.e., “members of the A.O.U.”).123

Again AOU representatives quickly came to the defense of their organization and the permit system. Chamberlain repeated his earlier claim that in his experience AOU scientists had freely given of their time and expertise to even the most rank beginner.124 Unable to restrain himself, Allen also entered the fray. The AOU president admitted that he had been granted authority to issue collecting permits under New York’s recently enacted bird protection law, but he vehemently denied giving favorable treatment to applications endorsed by AOU members. Thus far he had received fourteen applications, whose vouchers had been signed by twenty individuals. Most of these did not belong to the AOU. Allen claimed that none of the applicants had been denied permits because of unsatisfactory vouchers. According to Allen, the claims of discrimination lodged in recent numbers of the Ornithologist and Oologist were “not only unjust, but entirely false.”125

The level of tension between scientific ornithologists and other collectors gradually diminished as the bird protection committee withdrew from its active role in the bird protection movement and as the movement itself languished. But the rift that had opened up between scientific ornithologists and collectors was never fully repaired. Like the formation of the AOU and the institutionalization of the trinomial research program that came before it, the bird protection movement contributed to the breakup of what had been a congenial relationship during the heyday of the culture of collecting. Increasingly, cooperation gave way to mutual suspicion and even outright hostility.

ABANDONING BIRD PROTECTION

In the mid-1880s, at the height of the first bird protection movement, it looked to many as if the movement might be here to stay. Afraid that the rising tide of protectionism might eventually prevent even the scientific ornithologist from collecting birds, Brewster spent the summer of 1886 “quietly” gathering examples of the commoner birds around his vacation home in Concord, Massachusetts. He feared it might be his last chance to “fill out his series.”126 Brewster was wrong.

After a short burst of activity, the first phase of the bird protection movement quickly faded. The AOU bird protection committee published a second bulletin promoting a version of the AOU model law passed by the New York legislature in May 1886.127 AOU and Audubon members also lobbied successfully for the passage of a version of the law in Pennsylvania, Sennett’s home state, in 1889.128 But having secured what seemed to be adequate protective legislation in these two states, the committee seemed little inclined to expand its lobbying activities. By 1893 Sennett, who was preoccupied with the effects of the depression on his oil-machinery manufacturing business, asked the AOU to discharge his committee, arguing that the need for it was “no longer urgent, of late its function having been mainly advisory.”129

Of course, nothing could have been farther from the truth. By 1893 amendment and repeal had emasculated or repealed existing protective legislation, and the practice of feather-wearing had continued to grow at an alarming rate. Notwithstanding the initial success of the Audubon Society, the committee had run up against a wall of indifference and apathy. At the same time, the activity of bird protection had created a division between scientific ornithologists and the larger collecting community. Since most AOU members remained reluctant to cut themselves off entirely from that larger community, they willingly accepted Sennett’s request to dissolve the bird protection committee. Although AOU members reconsidered that action later in the meeting, the committee remained inactive for the next three years.

The Audubon Society suffered a similar fate. A period of robust membership growth in 1887, during which twenty thousand members joined, leveled off the next year. Even worse, few of the members were committed enough to subscribe to Audubon Magazine, which Grinnell hoped would provide the revenue to sustain the organization.130 Frustrated, Grinnell stopped publication of the magazine with its January 1888 issue and abandoned the Audubon Society. With the demise of the AOU bird protection committee and Grinnell’s Audubon Society, the bird protection movement seemed dead in its tracks.