Despite the rapid economic development of countries like China and India, there are still many parts of the world where people live in poverty. The World Bank has used income to group countries. Sometimes, we refer to parts of the world with very low per-capita income as “developing world” or “developing economies.” Of course, such terms have been criticized as the focus was on categorization instead of the people (Khokhar and Serajuddin 2015). Shifting to people, the low-income economies are plagued with people living in poverty. The World Bank (Global Monitoring Report 2016) has reclassified global extreme poverty as those living on $1.90 or less a day. In 2015, 9.6% of the world’s population lived under such a definition of extreme poverty. So our focus should be on how to address the needs and also help improve the welfare of the people in these economies.

Prevalence of worldwide extreme poverty. (Source: World Bank 2014)

In the remaining of this chapter, we will simply refer to as “developing economies” for regions that have significant population living under extreme poverty. Such economies can be in low-, middle-, or high-income countries.

Mobilize ecosystem to orchestrate the three flows

Product and process innovation

Designing the right value chain

Leveraging geo-political-economic lubricants

Servicization

1 Mobilize Eco-system to Orchestrate the Three Flows

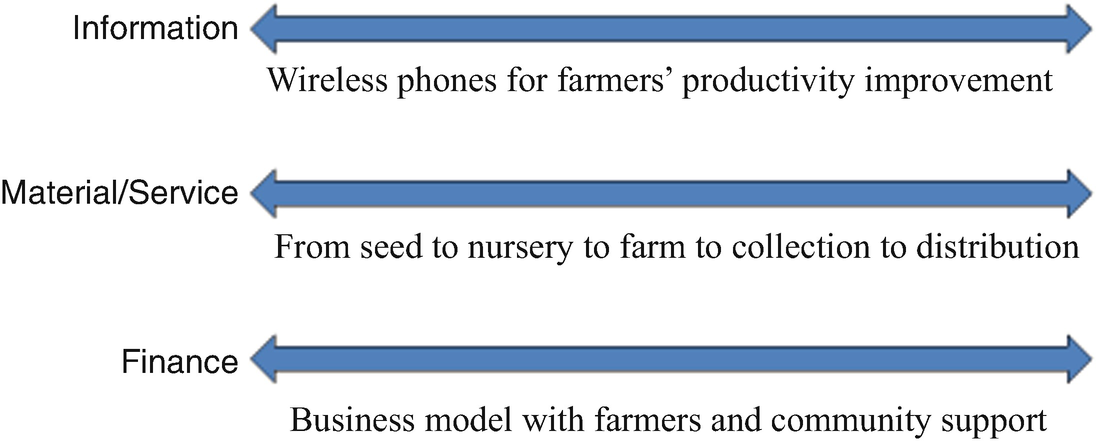

It is well known that the management of a supply chain or a value chain requires sound coordination of the information, material or service, and financial flows, which can span multiple organizations of the value chain. To help create values and stimulate development in developing economies, we must find ways to re-engineer these three flows under the often challenging environments of developing economies. In this section, we present two case examples to illustrate how the orchestration of the three flows can make a difference.

In Africa, it was estimated that at least 150,000 tons of shea kernels are consumed annually for cooking, as a skin pomade, for medicinal applications, in soap, for lanterns, and for cultural purposes at ceremonies (Rammohan 2010). On the other hand, 90% of shea nuts internationally were used for the food and confectionary industry and for cosmetics. Ghana is a major shea butter-producing country. Per-capita gross domestic product (GDP) in Ghana was $2201 in 2018 (Countryeconomic.com 2018), placing the country 141st out of 196 countries in terms of GDP. Agriculture constituted a major industry of the country. Shea butter trees grew wild in the country, allowing women farmers, many of whom illiterates, to easily pick the fruits from the ground. Loads of nuts were heavy, and it was common that the farmer had to walk down long dirt roads for several kilometers to the village market, where she became a price taker as it would be difficult for her to bring the crops back even if the price was not satisfactory.

Shea butter often had to go through multiple intermediaries before it reached the real buyer. As a result, the prices paid to the women farmers were just a fraction of the final price offered by the buyers. Farmers were also cash-strapped. Hence, when a farmer had unexpected financial needs such as a child getting sick needing hospitalization, she might have to sell her crop prematurely to a middleman who might take advantage of the situation by offering an extremely low price. A farmer therefore was often in extreme poverty position with little hope of recovery.

To alleviate this poverty cycle, SAP, PlaNet Finance, Maata-N-Tudu (MTA), and Grameen Ghana (GG) joined forces in 2009 to create a program to help the women farmers. The program required the orchestration of the three flows in butter production.

To begin, PlaNet Finance, MTA, and GG enlisted women into an organized group called the Star Shea Network (SSN). Such organizations had both physical and financial flow implications. The association gained scale for the farmers, so that they could have better negotiation power with buyers. This scale also affords more efficient trainings using videos on how to produce quality nuts and butter, management of finances, and even group dynamics. One major buyer, Olam International, was also enlisted to be part of the value chain as the market for the outputs of SSN. Olam also provided women with protective gear such as boots and gloves to safeguard against hazards such as snake bites when harvesting shea fruits. This should enable them to collect higher quantities over time.

To improve information flow, SAP developed a website (www.starshea.com) to help market the products to buyers all over the world. A specialized order fulfillment and management software was offered to the farmers to manage orders from buyers. Women are sent SMS text messages regarding logistics information, and market prices from Esoko, a market information exchange. SAP also developed the Microloan Management software to enable field credit officers to monitor their loan portfolios and calculate portfolio aging at a glance.

Innovating with the three flows for Ghana shea butter farmers

The number of women trained on quality nut and butter processing had grown to 22,000 in 2016; 40 shea companies have become buyers now.

Farmers received prices at 0.40 cedi (premium) and 0.35 cedi (standard) per kg, which were 82% and 59% increase over prices of distressed sales in the summer.

50% reduction of distressed sales by farmers.

Going forward, proper growing method, sanitized product, processing capabilities could lead to shea butter to be used as special products with higher values, for example, 100% natural handcrafted shea butter, shea body balm, and shea butter oil in cosmetics. This would further increase the incomes of the farmers.

The second case is based on hazelnut plantation in Bhutan. The GDP per capita in Bhutan was $3160 in 2018 (Plecher 2019), ranked 161st in the world. Among the total population, 69 percent lived in rural areas as farming was their main source of income. Out of this, 40 percent lived at subsistence level, with income at less than $1 a day (Hoyt and Lee 2011). To make ends meet, many young men had to leave the country to serve as migrant workers in neighboring countries, destroying the harmony and happiness of family life with their wives and children. Farmers had also deforested to make room to grow crops, resulting in severe soil erosion. Mountain Hazelnut (MH) was created as a social enterprise that would provide farming jobs with stable income, while at the same time improve environmental sustainability in rural Bhutan.

The co-founders of MH identified hazelnut as a crop that could be introduced in Bhutan, since the weather and soil conditions there were suitable. Hazelnut was a high-value crop with increasing demand worldwide. Yet, there was a constraint in supply, as not too many countries besides Turkey, Italy, and the United States could be fit for the cultivation of such a crop.

Farmers in Bhutan were initially skeptical, as they had never grown such a crop before, and it was known that much knowhow was needed to get good yield in growing hazelnut. MH has to innovate in new ways to orchestrate the three flows.

First is the physical flow. It might be too much to ask for the farmers in Bhutan to grow hazelnuts from seed to tree. Instead, MH found it more effective to cultivate hazelnuts tissues in in laboratories in Yunnan, China. Then, the tissues were flown to nurseries in the eastern part of Bhutan, where the tissues were grown to become baby trees. The farmers would then grow the baby trees to maturity. When the crops were ripe for harvest, the collection and transportation flows needed to be developed as well. Since Bhutan is a land-locked country, MH had to invest in logistics processes for the collection of the nuts, processing and warehousing them, then transporting them to cross the border to ports in India or Bangladesh possibly by trucks and rails, and then using ocean freight to get the products to the markets in Europe and China.

Moreover, MH innovated with the hillside conservation methods so that the trees could be planted on degraded slopes, in fallow land, or land otherwise unusable for food crops. The hazelnut roots could stabilize erosion-prone soil. This showed that MH was actually making a positive contribution to the environment, including stabilizing slopes, reducing erosion, protecting watersheds, reducing the amount of forest cut to obtain fuelwood, and sequestering firewood. It was a way to gain acceptance of the local communities to the introduction of the crop there.

One major challenge was that the physical road infrastructure in Bhutan was not well established; hence, it would be very difficult for the MH experts to travel to the farmers to give them advice from time to time on the proper ways to grow the crop, make appropriate irrigation and trimming work as weather changed, monitor their progress, diagnose potential problems, and help make treatment plans. Doing so would require innovations in the information flow. MH instituted a comprehensive system to track all its trees starting at the stage of tissue culture. The pictures of the tree and the farmer, his ID number, his field, and the GPS location were taken and tracked. MH built 25 solar-powered standalone weather stations across Bhutan to monitor weather conditions and climate change. Then, they used technologies such as mobile phones to make use of the weather information to provide farmers with advanced information on growing conditions, advice on orchard management, and adapt farming techniques to climate change. The phones could also be used to monitor the growth of the trees; to give instructions to farmers; and to provide right information to help farmers to irrigate, fertilize, and take care of the trees. It was possible for farmers to take pictures of the trees and send them to MH to diagnose problems or monitor progress. The information flow was supplemented by MH “field monitors” who would visit each field approximately once a month, depending on the season. They carried GPS devices and digital cameras, photographed the fields, filled out forms, and geotagged their photographs.

Besides the information and physical flows, MH also had to align the financial flows. First, MH could not sell the baby trees from their nurseries to farmers, even at a low price like $1 per tree. This was because even $1 was considered to be too high to the farmers, and many farmers also did not have the confidence that they could grow hazelnuts well to justify the investment. As a result, MH chose to give to the baby trees to farmers for free, on the condition that, when nuts were collected, MH would purchase them from the farmers according to preagreed upon prices. In addition, a new business model was created to gain the trust and acceptance of the local government and communities—MH would give 20% of the revenue back to the local communities.

Innovating with the three flows at mountain hazelnuts

Orchestrating the three flows in value chains has always been of great interest to operations management researchers. The challenge is to study how the three flows interact: in some cases, one may substitute another; in another, one can change the timing of another; and finally, we can use one flow to re-engineer the other flows. In developing economies, we have to understand the obstacles faced by having efficient, accurate, and timely flows, due to the lack of infrastructure in information, logistics, and finance.

2 Product and Process Innovations

For enterprises in developing economies to prosper and grow, or to add value to the overall value chain, innovations in products or processes may help or accelerate the development. Often times, such innovations may have to be initiated or resulted from investments by global enterprises. This is because global companies have the financial means and the engineering resources for such innovations, and that they have the necessary network of other companies to participate in making the innovations scalable. With the innovations, enterprises in developing economies can participate in the value chain, adding values and gaining from such participation. Global companies, of course, benefit from such developments, since the innovations can bring forth better products or improved processes to begin with, and they also gain valuable partners from these economies in the overall value chain. Partners can contribute as supply sources, as additional innovation collaborators, or as channels of markets.

The McDonald’s India case (Rammohan 2015) is one that I like to use to illustrate this point. McDonald’s entered the Indian market in the early 1990s. French fries were very popular with Indian customers, and the supply of MacFries was critical to the company’s success in India. In the beginning, McDonald’s joint venture partner McCain, itself the largest producer of frozen French fries and potato specialties, invested in French fry processing plant and machinery, and storage facilities. The resulting fries, however, were oily and limp, since the locally sourced potatoes did not contain the ideal amount of solids and the desired size. As a result, McDonald’s had to resort to imports from the United States, which was tricky, since the Indian government had many restrictions with high customs duties of 56% for potatoes, in order to protect the domestic industry. The lead time for imports was also long, at around 60 days. The alternative was to import frozen fries from New Zealand, the United States and Europe, again with steep import duties. As the market grew, it was clear that imports would not be a long-term solution to satisfy the demand for MacFries.

Recognizing that innovating in developing the right potato using the right growing method locally was the way to go, McCain’s began to work on potato agronomy―a branch of agriculture dealing with field crop production and soil management. This way, they could develop the right variety of potato so that potatoes could be grown and produced into French fries within India.

The first big focus would have to be cultivating the appropriate variety of potato where current suppliers had failed. McCain learned that cultivating potato seeds in high elevations was ideal, because seeds grown at high altitude had high vigor, enabling a commercial crop planted with those seeds to have higher yield and larger-sized potatoes. So, it instituted a Shepody potato seed multiplication program in the 13,000-foot high part of the Himalayan mountain range in Northern India. Seeds were sown in May, and harvested and brought back by donkeys in September.

Second, farmers would need to grow the full potatoes in a suitable, more accessible location than the Himalayas. Here, McCain conducted regional trials to locate the ideal growing area, and experimented with 13 types of potatoes to pinpoint the right variety. They also conducted management trials to identify the best combination of growing practices, and storage trials to figure out the best protocol for storing potatoes. From this experimentation, McCain zeroed in on the central Indian state Gujarat as the prime growing area. Three varieties were identified that could work. McCain established a one-acre demonstration farm to show farmers how to improve yields through better sowing, drip irrigation, and better harvesting techniques. The company transformed storage practices by applying a potato sprout suppressant in combination with using controlled temperature storage. This helped to avoid deterioration in potato quality during storage.

With seeds planted in September and October, the potatoes were harvested in February and March. Once they were processed into fries, the fries were frozen and sent to third-party logistics storage facilities or to McDonald’s distribution centers. From here, they were shipped to restaurants.

McDonald’s potato supply. (Source: McDonald’s India with permission)

The benefits to McDonald’s from using local fries were a 30 percent lower cost structure and no exposure to the fluctuating exchange rate. With local fries, inventory levels were reduced from an average holding of 15 days for imported fries to 6 days for local fries. The reduction in shipping time (60 days from the United States to less than a day for getting local product) also had a significant benefit for risk management and contingency planning.

There were benefits to farmers as well. Traditionally, farmers sold produce at the local “mandi,” or village market. Mandi sales and prices could fluctuate dramatically. The benefits to farmers of doing business with McCain were guaranteed sales of farm output, an increase in yields of 30–40 percent compared with “regular” potatoes, reduction in operating costs, increased and predictable farm income, and reduction in consumption of natural resources like water.

This case illustrated how local farmers could participate in the global value chain and increase their economic value capture, as a result of innovations created by a global enterprise. The innovations include experimentations to find the right potato types (product innovation) and the right farming and growing method (process innovation). The original objective of the global enterprise could be a selfish one, which in this case was about getting local supply to avoid the headache of having to import potatoes and fries with complex restrictions, heavy customs duties, and the risk associated with long lead time and fluctuating exchange rates. But the innovations have resulted in value-creation for the local farmers.

As discussed, product and process innovations often have to be initiated by a large-scale global enterprise that has the financial means and R&D capability to pursue such innovations. The beneficiaries are the small- and median-sized enterprises in developing economies, as well as the global enterprise itself. But how can one safeguard that such innovations might not spill over to competitors of the global enterprise, or does it matter? In addition, to convince and induce the players in the developing economies, such as the farmers in the case of McDonald’s, to be willing to take part in this undertaking, which was not without risks, what kind of incentive systems are necessary? These are all interesting research questions.

3 Designing the Right Value Chain

Besides the product and process innovations of the last section, innovations can be in the form of the value chain design, that is, the right configuration of what part to own and what part to outsource, and what part to be offshored and what part to be done on-shore. In developing economies, with uncertain environment and challenging infrastructure, figuring out the right configuration, or the right value chain, is important for successful ventures.

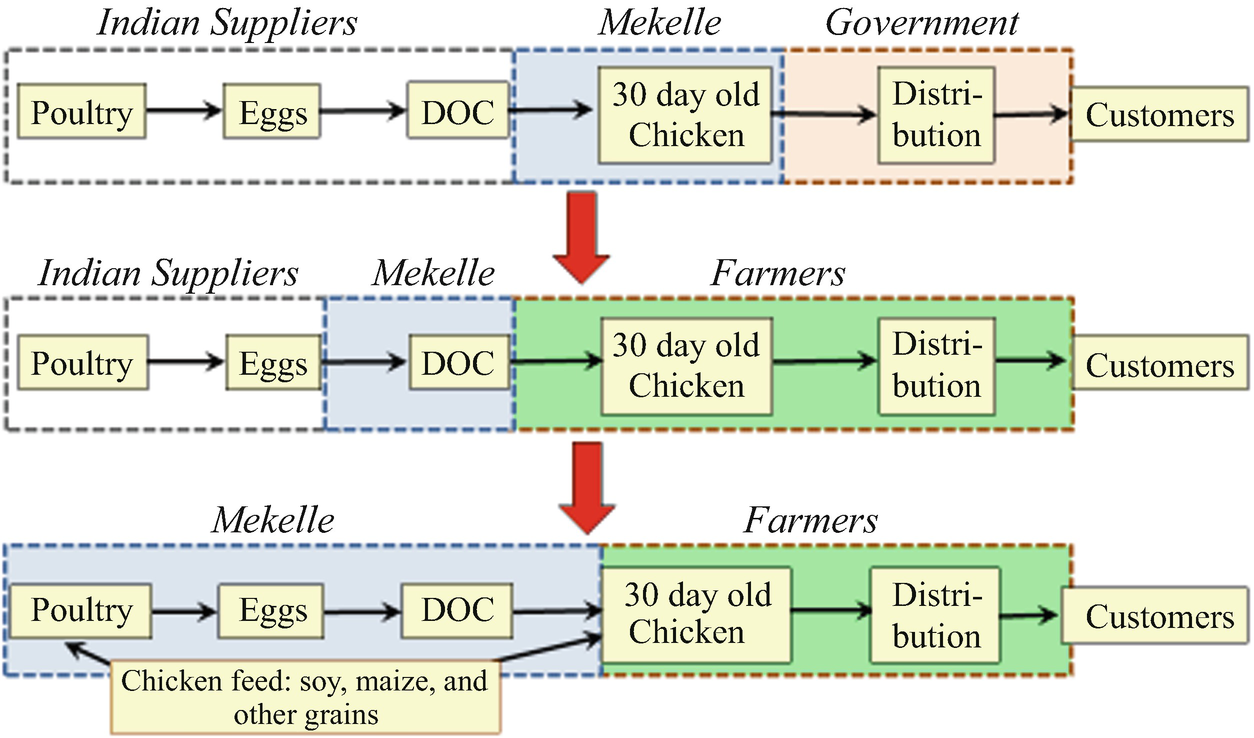

I will use the Mekelle poultry case to illustrate the importance of designing the right value chain (Elist and Kennedy 2014). The case was based on Ethiopia, a country in which chicken price was higher than that of beef due to chronic supply shortage, and had been rising over 100 percent in merely 5 years from 2005 to 2010. Despite the rising chicken price, many poultry farms had gone out of business in Ethiopia because of the steep cost of animal feed, contributing to the undersupply problem.

Mekelle Poultry Farms was formed in 2010 by two young entrepreneurs, after intensive negotiations with the regional government. To launch the company, the pair gave minority equity stake to the regional government, which enabled Mekelle be granted a 10-year lease on the poultry farm. Their deal with the government also came with some difficult stipulations: the pair could not legally sell any part of the farm; the chickens had to be sold at a certain size; and chicken sales were capped at $2.25 for month-old chickens. Mekelle planned to import live day-old chicks (DOCs), raise them, and then sell them to the government 1 month later for distribution to local markets. Their initial calculations suggested that they could achieve gross margins of 20 percent under this model. Thus, the initial value chain design was to procure DOC from abroad, and focus on raising the DOC to one-month old chicken. Thereafter, distribution was provided by the government. Mekelle felt that this would minimize its risks, as egg hatching to raise DOC required more substantial investment, and was risky, while with the government taking control of logistics distribution and sales, there was a level of stability and reliability that reduced risks.

However, Mekelle soon found that their design did not work well. First, their costs were much higher than they had anticipated. Each DOC would cost them $0.45, and the cost to transport them from India (a global leader in exporting DOCs) was $0.55 per DOC. Moreover, working with the government turned out to be not easy. While the government had guaranteed sales, distribution, and the cost of transportation, there was no stipulation on repercussions or remedies for Mekelle Farms should the government be late in picking up the chickens. In the initial months of operation, the government was picking up chickens closer to the 60-day mark than the 30-day mark, adding significant costs to feeding, vaccinating, and raising the chickens. They were also late in distributing the chickens to the local farmers after they had been picked up.

More damaging was the fact that it was unclear whether or not the government’s price cap included sales taxes, which ran up to 15 percent of the retail price. The government insisted that the $2.25 cap included taxes, which Mekelle Farms had not accounted for in their financial projections.

Faced with mounting losses, Mekelle had to revamp their value chain. Instead of importing live DOCs, Mekelle Farms decided to import eggs, which cost about $0.60 each, including transportation to the farm. The variable costs for hatching the eggs were minimal, and Mekelle Farms had to acquire the necessary equipment. The key is to ensure that the hatching process was sanitized to allow for healthy hatching of the eggs at a 60 percent rate to break even, and continue improving the rate so as to get some decent margin. This turned out to be a very difficult task, since it was not possible to control the quality of the imported eggs. Plus, there was the unexpected delay incurred at customs in Dubai, so that the inventory of imported eggs was stuck for days.

To succeed, Mekelle needed to gain greater control over the eggs, that is, they had to continue the vertical integration of the egg and DOC production stages. They decided to build a parent stock by importing 3450 chickens to produce eggs on-site. Eggs produced by the parent stock were incubated and hatched. With well-controlled process and sanitary conditions, they finally achieved an averaged hatch rate of 76 percent.

With egg-production brought in-house, input costs were now under control. But there were still significant costs related to raising the chickens for 30 full days. Mekelle Farms redesigned the outbound part of their value chain by selling DOCs to local farmers who would then raise the DCO to maturity, thereby capturing the highest margin segment of the value chain and offloading the riskiest portion of the operation.

Evolution of Mekelle Farms’ value chain design

In order to achieve this brand equity and establish greater trust with model farmers and end users, the team looked to leverage their relationship with the regional government, given the fact that the government was held in such high esteem among residents of the region. The partners realized that, as in most frontier markets, it was not a question of whether to work with the government, but rather a question of how. Their initial value chain design was built on the assumption that the government would be efficient, formal, and timely in logistics—assumptions that ultimately proved naive. Nevertheless, the government was adept at farmer mobilization, communication, and messaging, and proved to be a successful platform for building brand recognition and trust with farmers. The partners worked to incorporate the government’s strengths into their business model. Since taking over the poultry farm, Mekelle Farms had increased production from 15,000 chicks per year under government ownership to over 360,000 DOCs per year.

Value chain design requires answering the question of what to outsource and what to do in-house, as well as whether to do the task locally or remotely. In standard operations management problems, such design decisions have been the subject of research. In developing economies, the added complexities of the significant role of regional governments in either being help or obstacles must be factored into such decisions. Often, incentive alignment under special institutional and cultural settings is also necessary to make the right design decisions.

4 Leverage Geo-Political-Economic Lubricants

While economic values are often created in the private sector, we should not forget about the nonmarket forces that could either be lubricants or deterrents to business success. Deterrents could be in the form of taxes and customs, government regulations, corruptions and bureaucracy, and potential interventions by groups of vested interests such as NGOs. But there are lubricants, in the form of favorable trade treaties and agreements, local support in subsidies, and existing infrastructure investments by governments.

In Cohen and Lee (2020), the exponential growth of regional trade agreements indicated that there were opportunities in understanding the implications of the often complicated agreements. These agreements may serve as lubricants provided that they covered the right products and regions that could impact a company.

Similarly, there have been massive infrastructure initiatives that often involved multiple countries, which can also be lubricants for business opportunities. The Belt and Road Initiative is one such example (Lee and Shen 2020). Although there have been many skeptics as to whether this initiative was a political strategy for China’s expansion agenda, and whether many of the big-budget infrastructure projects could really come to fruition, the initiative did open up opportunities. The Belt and Road Initiative was supposed to aim at policy coordination to make it easier to cross borders between China and the countries along the Belt and Road; financial cooperation for easier flow of capital to invest in capacity and capability building in these countries; and investment in capacity building in logistics infrastructure and knowledge and technology transfer; and finally, harmonization of trade to reduce cross-border frictions.

I will focus on one example in which leveraging on such an initiative could lead to economic growth of a developing economy. The country of interest here is Ethiopia. Located in East Africa, the country has a population of 109 million in 2019 (ranked 12th in the world), 60% of which were below the age of 25. The country was among the poorest in the world, with per capita GDP of $790 in 2018 (The World Bank 2019). Yet the country had potentials, as the working population was relatively well educated, with English being a common foreign language. Their working wage was among the lowest in Africa, only 1/10 of that in China (Lee and Shen 2020). How could such potentials be developed?

The first lubricant was internal government support. The Ethiopian Government had identified the textile and apparel industry as a focal industry as part of its ambitious target to steer the country to be the leading manufacturing hub in Africa. Industry associations had been set up to provide training and skill improvements of workers. While the Belt and Road Initiative was being developed, major apparel companies started to explore and build up Ethiopia as part of their value chain. For example, H&M and PVH had started to source from the country. The moves by such major companies signaled that this could be a promising country to source from. Chinese manufacturers such as Huajian has also started manufacturing shoes in Ethiopia.

The second lubricant was external trade treatments. Ethiopian apparel and shoe exporters enjoyed duty-free access to the US market, thanks to the African Growth and Opportunity Act, which was renewed by the American government in 2015 for another decade. In addition, the country also enjoyed duty-free access to EU as well as preferential treatment to Japan.

Some lubricants were natural resources that required proper investments and developments to turn them to be of value. Ethiopia had great potential of cotton supply as inputs to textile and garment manufacturing. It was also one of the largest untapped livestock resources in the world. Working with the tanning industry, cattle, sheep, and goat hides could be turned into a variety of leather, thereby providing material sources for the shoe industry. Ethiopia also enjoyed low electricity cost, due to the country having one of the largest hydroelectric power dam in the continent.

Finally, the biggest break came in as logistics infrastructure support. Ethiopia is a landlocked country without a sea port. The only way to get products out through ocean freight is to get the products trucked to the nearest seaport in Djibouti, a neighboring country. The road to Djibouti was highly congested, and the port capacity of Djibouti in handling cargoes had already maxed out. Lead time delays would have deterred expansion of the manufacturing sector in Ethiopia. Under the Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese firms have invested heavily in a new national road network as well as an electrified railway line that connect Ethiopia to the port in Djibouti. Chinese firms had also invested in capacity-building in Ethiopia. The Hawassa Industrial Park was built by a Chinese contractor at an unprecedented speed of 9 months. The park was devoted solely to apparel and textile. The Chinese firms also brought in know-hows for the Ethiopian factories to improve their sustainability performances. For example, the Hawassa Industrial Park boasted zero-emission water treatment plant. The initial positive results had lured global brands, such as Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger, to manufacture in Ethiopia.

In the “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road” in 2015 (NDRC et al. 2015), the Chinese government has declared that “The Belt and Road Initiative aims to …, and establish entrepreneurial and investment cooperation mechanisms.” Hence, it was part of its game plan to foster entrepreneurial development in developing economies, so that there could be more new supply sources as well as demand points, leading to economic growth along the Belt and Road.

Besides government-led efforts, lubricants could exist through investments by global enterprises. In March 2017, Alibaba launched its first global digital free trade zone in Malaysia, as part of the electronic world trade platform (eWTP) that Alibaba founder Jack Ma wanted to champion. The vision of eWTP was to lower trade barriers and provide more equitable access to markets for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) around the world. The digital free trade zone consisted of a regional logistics center near Kuala Lumpur International Airport, with speedy storage, fulfilment, customs clearance, and warehousing operations. A one-stop solution platform had been set up to provide export facilitation support to local SMEs, with services ranging from marketing and customs clearance, to streamlined permit application procedures and tax declaration, etc. Such a platform would help stimulate developments of SMEs, enabling them to participate in the global value chains. In turn, such developments would bring forth economic benefits to the communities where such SMEs reside.

In 2018, a US$600 million Technology and the Innovation Fund was launched by eWTP (Daily Times 2018). “The fund’s mission is to drive strategic investments that helps companies accelerate their international expansion and support ideas that drive life-changing technological innovations around the world, including initiatives closely related to the “One Belt, One Road” push.” Lubricants therefore included direct financial support.

Lubricants are helpful to foster development, provided that your products or service and the geographies match up with the lubricants. However, these lubricants are not risk-free. For example, favorable trade agreements are subject to renewals, and changes in the terms of the trade agreements are common. They are often the result of political negotiations between countries that is beyond economic rationales. In addition, we have to recognize that a lubricant to you may also be a lubricant to your competitor. When multiple companies move in the same direction, it changes the economics of the original initiative. For example, as more and more companies are manufacturing in Ethiopia, even the new highways connecting the manufacturing hubs to Djibouti will become congested, and the logistics bottlenecks may make it no longer attractive to manufacture there. This calls for research that incorporates new dimensions in risk management and modeling the effects of externalities and network effects.

5 Servicization

Developing economies face challenges that the local workers might not have the education and skill level for the particular business needs for growth, and the poor logistics infrastructure would also inhibit easy access and movements to provide support in such situations. The result is that, even if there were powerful equipment that could enhance productivity in the developing economies, the full potential of such equipment could not be realized. Here, one can innovate in the form of providing the usage of the equipment as a service, that is, “servicization.” Orsdemir et al. (2018) defined servicization as “Servicization is a business strategy to sell the functionality of a product rather than the product itself.” It is a way to enable workers and small businesses in developing economies to make use of productivity enhancement tools and equipment, so as to improve their business performances.

I will use the Netafim case (Michlin 2006) to illustrate this. Agriculture had traditionally been a low-tech industry. However, innovative technologies have been introduced into the agricultural industry that could improve the productivity of the farm, enhanced logistics and distribution, and allow the farmers to capture greater values of their farm produce (see Lee et al. 2017). Irrigation was one part of the farming production process, which has seen significant technological advancements.

Water shortage has been a major challenge faced by many parts of the world, and it was estimated that, by 2050, two-thirds of the population will be faced with water scarcity (Mancosu et al. 2015). Agriculture required fresh water and so it has been the industry that had been hit hard with the water shortage problem. Farm irrigation consumed significant amount of water and, hence, innovative methods to reduce water usage in irrigation have been a major focus.

The irrigation market was generally divided into two segments: low-pressure irrigation and high-pressure irrigation. Low-pressure irrigation was almost synonymous with flood or furrow irrigation, a method that was based on flooding all or part of a field. Though flood irrigation wasted water and caused soil erosion, it was still widely used around the globe, especially in underdeveloped countries due to its low cost. Drip irrigation was a method of controlled, high-pressure irrigation in which water was either dripped onto the precise part of the soil surface, or delivered to the root system of plants. Drip irrigation saved water usage significantly, and it prevented leaf diseases and improve crop yields. The main barriers to adoption were its relatively high price and that it required the farmer to be skilled in installing and operating the equipment to achieve maximum benefit from the system.

Netafim was one of the world leaders in drip irrigation. Its irrigation system consisted of networks of drip-points that were armed with microprocessors, which allowed direct control of the timing, speed, and duration of the drips. Such controls could be customized based on weather conditions, the soil environment, and the kinds of crops that the farmers were growing. By 2017, Netafim’s annual revenue had reached almost $1 billion with earnings of $133 million (Arnold 2018).

While Netafim had been successful in selling their powerful drip irrigation systems to farmers in the United States, Italy, and Australia, etc., the company’s global expansion in developing economies faced roadblocks. Agriculture was the most important industry sector for many developing economies, and so the potential of Netafim’s system for such economies was great. But the challenges in these economies were many. First, farmers were often uneducated and so requiring them to operate such a sophisticated system was almost impossible. Second, farmers lacked financial means to purchase such a system, and financial institutions like the IFC, which usually would be the source for such applications, were reluctant to give out loans to farmers as it was difficult to expect that the farmers would be able to use the system well, improve crop yields, and increase their incomes, thereby being able to pay the loan back. Third, even if Netafim was willing to invest in having their engineers to travel to the farms to help tune the controls of the system periodically, the logistics to reach the farmers could be equally challenging, as many of the farms were in rural areas without access to paved roads.

To penetrate to the markets in developing economies, Netafim initiated the development of a system called Crop Management Technologies (CMT). The first models included a collection of sensors, some of which were soil-installed, while others worked in the air. These sensors received regular input on levels of soil water content, salinity, fertilizer, and meteorological data. Also included was an irrigation computer that controlled irrigation and fertilization frequency, as well as scheduling. The input received was radio-transmitted to a central control system, with figures/graphs made visible on the computer screen, thus enabling a controller to review the results and make any required modifications. CMT’s latest generation device allowed Netafim agronomists stationed in Israel to monitor data over the Internet and guide farmers by phone, mail, or online communications. Netafim’s narrow plastic pipes, which revolutionized the field of drip irrigation a half-century ago, also contained sensors and software that allowed farmers to monitor and control their fields via mobile phone (Fig. 6).

The value of CMT was that a farmer, who did not have much knowledge or skill in operating such an advanced system, could enjoy the productivity benefits of having such a system. The Netafim controller would be doing the job of what a sophisticated farmer in developed economy in monitoring and controlling the system. Indeed, with the advanced data analytics inside Netafim, the drips were even more precise and optimal than what most farmers would be able to do. The CMT setup could also be used to help farmers apply fertilizers and manage energy in more optimal manner. This is like servicization of the irrigation task of the farmers.

As an added benefit, the collection of Web-based version of the CMT would enable Netafim to receive direct streams of information from hundreds of thousands of fields around the world. Netafim’s agronomists would then use this data for research and would serve as online consultants and as facilitators of information-sharing between farmers. For example, farmers, growing similar crops in similar growing conditions in different countries around the world, would be able to share best practices through the portal and help each other with fertilization formulas, pesticide fumigation, irrigation plans, etc.

Netafim’s crop management system

Servicization is a useful way to help farmers and business people in developing economies to make use of advanced technological tools available in developed economies. Servicization often resulted in new business models, and so is a key part of the emerging field of operations management research on business model innovations. As part of servicization launch, a company is selling service instead of a product. Service can be paid based on fixed fees, or on performance. The latter showed that the research on performance-based contracts would be important. Finally, although farmers in developed economies might be limited to the servicization model, some of the more sophisticated farmers there, or farmers in developed economies as strategic customers, could potentially have the choice of owning the equipment versus buying the service. In pricing their equipment and service, Netafim needs to consider some of their customers as strategic, and make the proper pricing decisions in light of such strategic customers.

6 Summary

Poverty alleviation requires economic growth in the developing economies. The best way to foster economic growth is through entrepreneurship as well as increasing engagement of those economies into the global value chains. There are inherent challenges faced, due to underdeveloped infrastructures and skill gaps. But innovations in the value chain could help to overcome these challenges, unleashing potential economic and social values. Hence, value chain innovations can be a significant enabler or accelerator for value creation in such economies.

Finally, this topic can also be a great opportunity for creative, impactful, and rewarding research ground for supply chain and logistics professionals.