Uranus was discovered in 1781 by William Herschel, who noticed it as a faint object through his telescope when scanning the constellation of Gemini. At first, Herschel thought that the new object might be an incoming comet, but before long its orbit was calculated and it was shown to circle the Sun at a vast distance beyond Saturn – around 20 times the distance of the Earth from the Sun, and so far away one orbit takes it more than 84 years to complete. Uranus is another giant ball of gas, with a diameter more than four times that of the Earth.

If you know exactly where to look, Uranus can just about be seen with a keen naked eye if the sky is clear and dark. It’s easy to spot in binoculars, but to be able to discern its disk a high magnification is required. Through a high-power eyepiece, Uranus appears as a tiny featureless disk with a pale greenish hue. Little of interest was revealed by the Voyager 2 space probe as it flew by the planet in February 1986, except for a dusky polar region and a few vague bands and spots. It wasn’t the planet itself that proved to be the highlight of Voyager 2’s flyby through the Uranian system, but its amazing retinue of small satellites, all of which are too faint to be seen through backyard telescopes. Uranus also has a ring system, but this is far less spectacular than that of Saturn, and so faint that it can only be seen on images taken through big telescopes.

Uranus, imaged by the Keck Observatory.

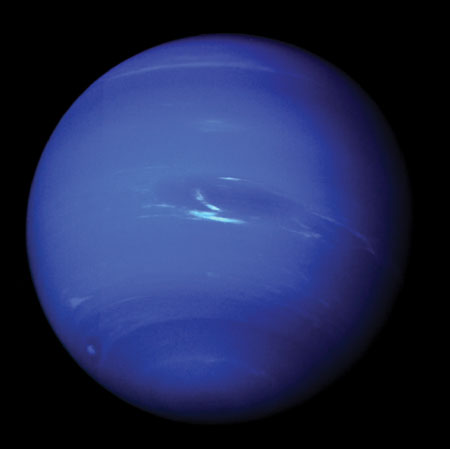

Discovered in 1846 following a concerted telescopic search, Neptune is the smallest of the Solar System’s gas giants. With an orbital period of 164 years, Neptune lies at the staggering distance of 4.5 billion kilometres from the Sun – so distant that sunlight takes about four hours to reach it. Despite its immense distance, Neptune’s atmosphere is surprisingly active, as revealed when Voyager 2 sped past the planet in August 1989. The strongest winds in the Solar System were measured to gust here at more than 2,000km/hour (1,243mph), and Voyager imaged a number of prominent atmospheric features, including a bright cloud dubbed ‘the Scooter’ and a ‘Great Dark Spot’ (like Jupiter’s Great Red Spot), which was larger than the Earth. By 1994 the Hubble Space Telescope showed that these features had faded away, but similar ones elsewhere on the planet had sprung up.

Because of its faintness, Neptune is more challenging to locate than Uranus. Too dim to be seen with the unaided eye, it can be spotted as a star-like point through binoculars. Neptune’s disk is tiny, and to resolve it requires at least a 100mm telescope with a minimum magnification of 200x. Observers might just be able to discern a slight bluish tinge – the result of methane gas absorbing the red wavelengths of sunlight falling upon it. Needless to say, obvious features on Neptune are not visible through amateur telescopes.

Neptune, imaged by NASA’s Voyager 2 probe.

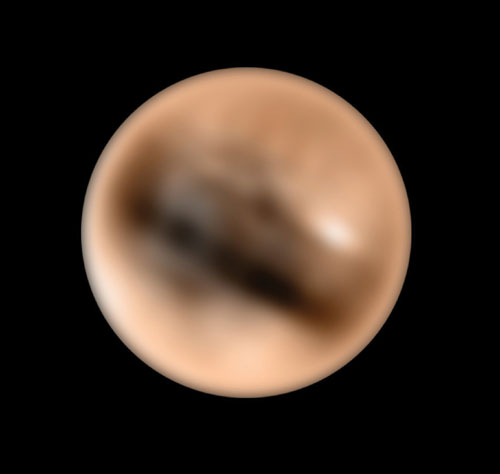

Beyond the eight officially recognised planets are numerous sizeable ice worlds. Pluto, the most famous of these, was discovered by the sharp-eyed Clyde Tombaugh on a photographic plate in 1930. Just two-thirds the size of our own Moon, images of Pluto taken by the Hubble Space Telescope have revealed a vague patchwork of light and dark areas, but what these might be is anyone’s guess until NASA’s New Horizons probe flies by in 2015. Most amateur astronomers have never observed Pluto – it is far too faint to be seen in anything smaller than a 250mm telescope, and even when seen through a really large telescope at maximum magnification it just looks like a faint star. Still, the thrill of actually seeing Pluto captivates many stargazers, worth every effort made in the hunt.

Pluto in true colour, imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope.