![]()

Prostitutes and Seamen’s Wives on Board in Port

Now our ship is arrived

And anchored in Plymouth Sound.

We’ll drink a health to the Whores

That does our ship surround.

Then into the boat they gett

And alongside they come.

“Waterman, call my Husband,

For I’m damb’d if I know his name.”

—“A Man of War Song”

IN A LETTER DATED 19 April 1666 to Samuel Pepys, at that time clerk of the acts, Admiral John Mennes, comptroller of the British Royal Navy, complained that the ships of the navy “are pestered with women.” “There are,” wrote Mennes, “as many petticoats as breeches” on board, and, he added, the women remain in the vessels “for weeks together.”1

Naval chaplain Henry Teonge described the scene he witnessed in the frigate Assistance in 1675 on the night she entered the Thames estuary on her way from London to Dover:

Our ship was that night well furnished but ill manned, few of them [the seamen] being well able to keep watch had there been occasion. You would have wondered to see here a man and a woman creep into a hammock, the woman’s legs to the hams hanging over the sides or out at the end of it. Another couple sleeping on a chest; others kissing and clipping [hugging], half drunk, half sober, or rather half asleep.2

A hundred and thirty years later, the scene on board had not changed. Whenever a naval ship came into port, hundreds of women, most of them prostitutes, joined the men on the already crowded lower deck and remained until the vessel put to sea. The seaman William Robinson, who served in the Royal Navy from 1805 to 1811, described the arrival of his ship at Portsmouth, England:

After having moored our ship, swarms of boats came round us…and a great many of them were freighted with cargoes of ladies, a sight that was truly gratifying, and a great treat, for our crew, consisting of six hundred and upwards, nearly all young men, had seen but one woman on board for eighteen months.… In the course of the afternoon, we had about four hundred and fifty [women] on board.

Of all the human race, these poor young creatures are the most pitiable; the ill-usage and the degradation they are driven to submit to are indescribable; but from habit they become callous, indifferent as to delicacy of speech and behavior, and so totally lost to all sense of shame that they seem to retain no quality which properly belongs to women but the shape and name.…

On the arrival of any man of war in port, these girls flock down to the shore where boats are always ready.… Old Charon [the boatman who carries the women out to the ships] often refuses to take some of them, observing to one that she is too old, to another that she is too ugly, and that he shall not be able to sell them.… The only apology that can be made for the savage conduct of these unfeeling brutes is that they run a chance of not being permitted to carry a cargo alongside unless it makes a good show-off; for it has been often known that, on approaching a ship, the officer in command has so far forgot himself as to order the Waterman to push off—that he should not bring such a cargo of d——d ugly devils on board, and that he would not allow any of his men to have them.… Here the Waterman is a loser, for he takes them conditionally; that is, if they are made choice of, or what he calls sold, he receives three shillings each; and, if not, then no pay.… Thus these poor unfortunates are taken to market like cattle, and whilst this system is observed, it cannot with truth be said that the slave trade is abolished in England.3

While Robinson and other seamen expressed their pity for the prostitutes, commissioned officers, from their isolated vantage point high on the quarterdeck above the fray of the lower deck, showed little sympathy for the unfortunate women, accepting their presence on board as an unsavory but necessary situation.

Horatio Nelson’s noted rapport with his men did not extend to their women, or at least not to their temporary women. He wrote to Admiral John Jervis in 1801, “I hope there will be orders to complete our complement, and the ship to be paid on Saturday. On Sunday we shall get rid of all the women, dogs, and pigeons, and on Wednesday, with the lark, I hope to be under sail for Torbay.”4

Even the nineteenth-century reformer Admiral Edward Hawker, who first brought the situation of the prostitutes to public attention, was concerned only with getting the women out of the ships, not with improving their lot. A pamphlet that Hawker published anonymously in 1821 presents a highly colored but not inaccurate picture of a naval ship in port in the period following the Napoleonic Wars:

The whole of the shocking, disgraceful transactions of the lower deck is impossible to describe—the dirt, filth, and stench…and where, in bed (each man being allowed only sixteen inches breadth for his hammock) they [each pair] are squeezed between the next hammocks and must be witnesses of each other’s actions.

It is frequently the case that men take two prostitutes on board at a time, so that sometimes there are more women than men on board.… Men and women are turned by hundreds into one compartment, and in sight and hearing of each other, shamelessly and unblushingly couple like dogs.

Let those who have never seen a ship of war picture to themselves a very large low room (hardly capable of holding the men) with five hundred men and probably three hundred or four hundred women of the vilest description shut up in it, and giving way to every excess of debauchery that the grossest passions of human nature can lead them to, and they see the deck of a seventy-four-gun ship the night of her arrival in port.5

THE SCENE IN PORT, AT HOME AND ABROAD

It is difficult for us today, familiar as we are with the order and discipline of modern naval vessels, to realize what pandemonium existed in the sailing ships of the Royal Navy anchored in Portsmouth, Plymouth, and other naval ports.

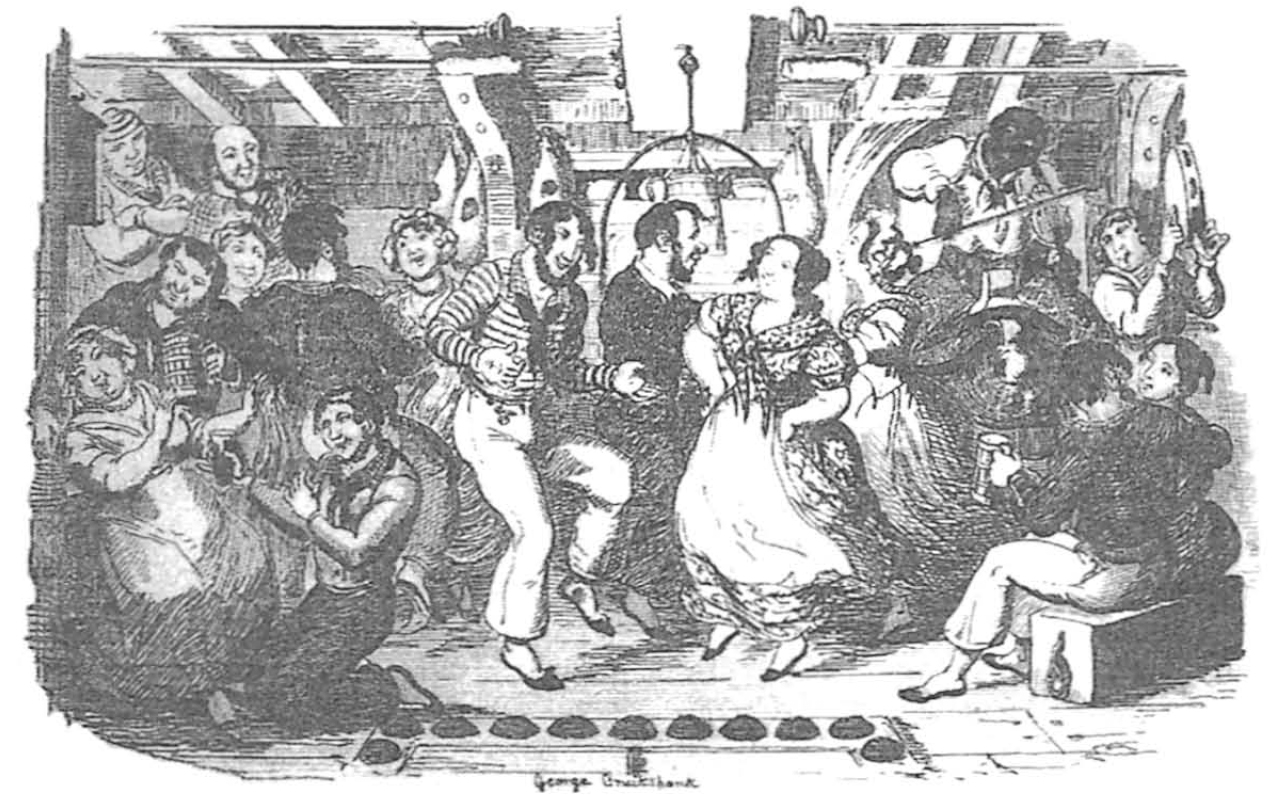

Not only did hundreds of women share the lower deck with the seamen. There were also children of all ages, from toddlers brought on board by the seamen’s wives to adolescent boys in the crew who frolicked around the decks where the crowds of men and women were drinking, dancing, and fornicating. The tradesmen, always referred to as “the Jews,” and the bumboat men and women, whose boats brought merchandise out to the ships, set up stalls on board and hawked their wares among the crowds as they would in a marketplace on land.6 They sold, on credit until payday, fresh fruit, clothes, trinkets, and any other items that a sailor back from a long voyage would fancy—including liquor, which they, like the prostitutes, smuggled on board. Dogs, cats, parrots, and other pets added to the general disorder.7 The fifty-gun Salisbury returned to England from Newfoundland in the 1780s with seventy-five dogs on board, approximately one for every four men.8 At night, when the hammocks were up and sleep had overcome the crowd, a cacophony of snores issued from hundreds of throats, made more sonorous by the great quantity of liquor imbibed throughout the day.

Officers became so inured to the presence of large numbers of prostitutes in their ships that the women were not always sent on shore even when a ship was inspected by a royal visitor; they were merely hidden away. The seaman William Richardson tells of the visit of Princess Caroline to H.M.S. Caesar during which the princess not only caught a glimpse of “the girls” but actually acknowledged them:

On May 11, 1806, Her Royal Highness Caroline, consort to His Royal Highness George, Prince of Wales [later, King George IV]…paid our Admiral [Sir Richard Strachan] a visit on board the Caesar, accompanied by Lady Hood and some others of distinction, and were received with a royal salute of twenty-one guns. The ship had been cleaned and repaired for the purpose, and all the girls (some hundreds) on board were ordered to keep below on the orlop deck [far in the depths of the vessel] and out of sight until the visit was over.

As Her Royal Highness was going round the decks and viewing the interior, she cast her eyes down the main hatchway, and there saw a number of the girls peeping up at her.9

Princess Caroline was not one to avoid causing a little public embarrassment if it amused her to do so. Although Richardson may have improvised on her actual words, there is no reason to doubt that the situation was much as he described it:

“Sir Richard,” she said, “you told me there were no women on board the ship, but I am convinced there are, as I have seen them peeping up from that place, and am inclined to think they are put down there on my account. I therefore request that it may no longer be permitted.”

So when Her Royal Highness had got on the quarterdeck again the girls were set at liberty, and up they came like a flock of sheep, and the booms and gangway were soon covered with them, staring at the Princess as if she had been a being just dropped from the clouds.10

Crowds of women came on board Royal Navy vessels in foreign harbors, too. In West Indian ports it was customary for officers to arrange with plantation owners to send large groups of slaves—black female field hands—to their ships. Captain Edward Thompson’s description of the scene in ships at Antigua in the 1750s reveals the attitudes of officers of his day: “Bad smells don’t hurt the sailor’s appetite, each man possessing a temporary lady whose pride is her constancy to the man she chooses. I have known 350 women sup and sleep on board on a Sunday evening and return at daybreak to their different plantations.”11 It seems most unlikely that the women had any part in the choice of whom they slept with, and as for bad smells, they could not have smelled worse than the men, who had been cooped up in their stifling ship for months with few if any baths or changes of clothing. Even when a seaman was taken with the urge to bathe, his only bathing facility was a bucket of cold seawater. There were no uniforms for seamen; they had to provide their own clothing, and many a man had only the clothes he was wearing when he first came on board. When a seaman got around to doing his laundry, also in a bucket of salt water, he first bleached it in urine, which was collected in a large barrel for this purpose.

In 1788 Prince William Henry (later crowned William IV), when in command of the thirty-two-gun Andromeda at Jamaica, included the following instructions in his orders to his officers: “Order the 8th, requesting and directing the first lieutenant or commanding officer to see all strangers out of his Majesty’s ship under my command at gun-fire [sunset] is by no means meant to restrain the officers and men from having either black or white women on board through the night so long as the discipline is unhurt by the indulgence.”12 Even after 1833, when slavery was abolished in the British West Indies, officers continued to arrange for female plantation workers to come into their ships. As late as the 1840s a frigate captain at Barbados ordered his first lieutenant to secure a black woman for every man and boy in his crew.13

The navies of other countries also took prostitutes on board in foreign ports. While the U.S.S. Dolphin, the first United States warship to go to Hawaii, was at Honolulu in 1826, her commander, Lieutenant John Percival, learned that the governor of the island of Oahu had been induced by the leader of the Protestant missionaries to issue an order that women should no longer be allowed to go for immoral purposes on board vessels anchored there. Percival was furious. Since women had been allowed on board the British frigate Blonde, under the command of Captain the Right Honorable George Anson, Lord Byron, when she visited Honolulu the previous year, Percival, a touchy man, viewed this ruling as a personal insult and an attack on the honor of the United States Navy. He announced that he would not leave the islands until women were allowed to go on board the Dolphin. “I would,” he declared, “rather have my hands tied or even cut off and be carried home maimed as a criminal than to have it said that Lord Byron was allowed a privilege greater than was allowed me.” The governor rescinded the order for the duration of the Dolphin’s visit, and even the mission school was emptied of girls, who were rowed out to the Dolphin amid the happy shouts of her crew.14

WHY PROSTITUTES WERE ALLOWED ON BOARD

Why did the Royal Navy for so many centuries permit hundreds of prostitutes to live in its ships? The sad truth is that a great percentage of seamen were taken into the navy against their will, forced on board by press gangs. Living conditions were terrible, and pay was both meager and slow in coming. If men were given shore leave, they deserted. Therefore, once a seaman was brought on board, he might not get out until his vessel was decommissioned, and commissions usually extended three to five years, often even longer on foreign stations. He also might be transferred from one ship to another with no leave between the two.15

Naval vessels were anchored far from shore, and the men were not encouraged to learn to swim. In addition to the marine patrols on board, some captains even went so far as to have special guard boats circling their ships throughout the night to prevent seamen from slipping away under cover of darkness. Dr. Samuel Johnson, the eighteenth-century lexicographer and noted literary light, was not exaggerating much when he remarked, “No man will be a sailor who has contrivance enough to get himself into a jail; for being in a ship is being in a jail with the chance of being drowned. A man in a jail has more room, better food and commonly better company.”16

Commissioned officers realized that there was a limit to what seamen would endure before they mutinied, and so, since the men could not seek sexual gratification on shore, when a ship came into harbor, prostitutes were allowed to stay with the seamen on board. (It was also feared that there would be an increase in cases of homosexuality if the men did not have some opportunities for concourse with women.)

Complaints about lack of leave go back to the Dutch wars in the seventeenth century. In a petition to Oliver Cromwell in 1654, seamen protested the order that denied them leave and kept them “in thraldom and bondage.”17 The situation did not improve in the eighteenth century. Following the great mutiny at Spithead in 1797, lack of leave was the only major grievance of the mutineers that was not remedied. It was not until the 1830s, by which time men were no longer pressed and living conditions on board were greatly improved, that most captains granted leave on a regular basis. (There were no Admiralty regulations or guidelines regarding shore leave; it was entirely the responsibility of each vessel’s commander to decide how much, if any, leave to give.)

A few humane officers, who had treated their crews decently, dared to give leave, and their men, grateful for the indulgence, proved they could be trusted. Just prior to the 1797 Spithead mutiny, Admiral Charles Vinicombe Penrose let his men go ashore in rotation, a few at a time, and only two deserted. Captain Anselm John Griffiths lost only eleven out of three hundred when he gave his crew leave in 1811.18 These were exceptional cases, however. Most commissioned officers were part of the upper middle class or of the gentry, and in the sharply delineated class system of their time they looked upon their seamen, who were part of the underclass, as a separate, inferior species who could be controlled only by harsh discipline.

The Seaman’s Hard Lot

To understand the horrors endured by the seamen’s prostitutes, it is necessary to know how brutalized the seamen themselves were.

Life on land was hard for a man of the poorer classes, but it was seldom as bad as life on the lower deck of a naval vessel. Naval punishment was often draconian; a seaman could be flogged for the most minor offense. Drinking water was foul, and the men’s diet was monotonous as well as unhealthy, consisting primarily of heavily salted meat, dried peas, sea biscuits, and hard cheese. The seamen slept, ate, and spent what leisure time they had on the badly ventilated lower gun deck, which reeked of bilge water, human waste, and sweat.

The great killer of naval seamen was neither shipwreck nor battle but disease. Between 1792 and 1815, during which time Britain was, except for one year, continuously at war, half of all naval deaths were from disease. Although the number of deaths gradually decreased over the years as medical treatment, diet, and sanitation improved, the death rate continued to be dreadfully high. Sir Gilbert Blane, the great naval physician, reported that in 1815 the navy’s mortality rate from disease was 1 in 30.25, although most of the seamen were in the prime of life, between the ages of twenty and forty. National mortality for that age group was only 1 in 80.19

Scurvy, caused by a lack of vitamin C, was a ghastly disease that rotted the gums so that the teeth fell out, and a major killer of seamen whose diet was almost totally lacking in fresh fruits and vegetables and fresh meat. It was not until 1795 that a daily issue of lemon or lime juice was required in all ships; the use of limey as a nickname for British sailors came from this requirement.

Typhus, spread by body lice and rats, often reached epidemic proportions in the channel fleet, where infected recruits were sent on board still wearing their lice-ridden clothing. Influenza, consumption (tuberculosis), dysentery, and smallpox also took a heavy toll.20 The seamen’s greatest fear, however, and rightly so, was that they would be sent to the West Indies, where yellow fever raged. It was not unusual for a ship with a complement of several hundred to lose all but a handful of her men to that disease.21

Although it was not known that tropical diseases such as yellow fever and malaria were carried by mosquitoes, officers were aware that men sent on shore were especially vulnerable to these maladies, especially if they remained into the evening, when mosquitoes are most active. This knowledge provided another reason for keeping the men on board, anchoring far from shore, and, in turn, sending crowds of women into the ships.

A man tempted to desert was seldom deterred by thoughts of future pay. Wages remained the same from 1653 until 1797, although the economy had greatly inflated during those 144 years.22 Seamen’s wages were raised following the 1797 mutinies at Spithead and the Nore, but this does not mean that they were paid on time. The navy was continuously short of cash, and the men waited months, even years, for their pay. In 1811 Lord Thomas Cochrane begged Parliament to see that seamen were paid on a regular basis. He presented a list of ships in the East Indies whose crews had not been paid for eleven, fourteen, and even fifteen years, but his fellow parliamentarians were unmoved. The response to Cochrane’s plea was that the situation “was much to be regretted, but it was often unavoidable.” The subject was dropped.23

On top of all this was the fact that a large percentage of naval crews had been forced on board in the first place—grabbed by press gangs with no chance to arrange matters at home before they were taken away. In wartime—which in the Georgian era was most of the time—ships were often so short of men that it was necessary to call for “a hot press” in which gangs were sent out to grab any man they could catch who could not prove himself a member of the gentry. Every coastal town in England had its terrible stories, only slightly exaggerated in the telling, of gangs who broke into houses and pulled men from their beds, or of bridegrooms captured at the altar and carried off to sea.

Press gangs also waylaid merchant vessels as they headed home and took off their most experienced seamen. Sometimes they removed the entire crew, putting their own men on board to bring the vessel in. It was heartbreaking for sailors to be impressed just when they were returning home from a long voyage.

For a time, convicted smugglers who could not pay a fine were offered a choice of jail or the navy, but so many agreed with Dr. Johnson and chose jail that the law was changed so that all convicted smugglers were sent into the navy.24

The most disaffected of all the seamen were the foreigners—they made up an average of around 12 percent of crews during the Napoleonic Wars—especially those taken on board from captured enemy ships.25 Nor were the black slaves, sent into the navy by their masters, stirred by patriotic fervor. Slaves served as seamen at least until 1772, when slavery was effectively abolished in Great Britain; and in West Indian ports, until its abolition there in 1833, slaves were brought on board to work ships whose crews had been decimated by disease.26

Officers were well aware of the disaffection of large numbers of their men, but there was little they could, or would, do to compensate for the men’s hard life and lack of freedom, except to provide them with great quantities of liquor—there was an allowance of a gallon of beer and a half-pint of rum per man per day—and the company of women when ships were in port.27 Admiral Charles Vinicombe Penrose, writing in 1824, summed up the officers’ attitude about having prostitutes on board: “Allowing women of bad character [on board] is an ancient custom, always forbidden, either by general or particular instruction, but always allowed…as a necessary or rather unavoidable evil.”28

Admiralty Regulations

A Tudor disciplinary code predating 1553 included the order, “No woman to lie a shippe borde all nyght.”29 The fact that it was necessary to issue this regulation indicates that it was commonplace for women to spend the night on board even at that early date. By the eighteenth century the tradition of allowing huge numbers of prostitutes to frequent naval ships was firmly established.

In the first printed Regulations and Instructions Relating to His Majesty’s Service at Sea, issued in 1731, no mention was made of women coming on board in port, although commanding officers were ordered “not to carry any woman to sea…without orders from the Admiralty.”30 By the 1750s, however, the following peevish instructions had been appended under “Additional Regulations”: “That no woman be ever permitted to be on board but such as are really the wives of the men they come to, and the ship not to be too much pestered even with them.”31 These instructions were in a section entitled “Rules for Preserving Cleanliness,” in which officers were also ordered to see that “the men keep themselves as clean in every respect as possible”—a vague directive if ever there was one—and were instructed “to prevent peoples’ easing themselves in the hold or throwing anything there that may occasion nastiness.”32 Moral cleanliness was not distinguished from physical cleanliness. (At that period the euphemism unclean acts was often substituted for the taboo words buggery and sodomy.)

The instruction to admit only wives of seamen was seldom followed, and a captain who tried to enforce it was made fun of by his fellow officers. Sir William Henry Dillon noted in his memoirs that Captain James Gambier, “a strictly devout, religious man bordering upon the Methodist principle,” upon taking command of the Defence in 1793 ordered that all women coming on board must show wedding certificates. “Those that had any produced them,” Dillon reported, “and those that had not, contrived to manufacture a few. This measure created a very unpleasant feeling amongst the tars.”33

Equally bad feelings resulted from the following orders issued by Captain Richard G. Keats in H.M.S. Superb in 1803:

In port, women will be permitted to come on board, but this indulgence is to be granted (as indeed are all others) in proportion to the merits of the men who require them, and upon their being accountable for the conduct of the women with them.

The commanding officer in port will therefore permit such men to have women on board as he may choose: and he will direct the master-at-arms to keep a list agreeable to the following form; which he will carry to the commanding officer every morning for his inspection.34

The following questions were to be answered: “Women’s names? With whom? Married or single? When received on board? Conduct?”

It seems highly unlikely that the master-at-arms was capable of keeping a detailed daily list of the individual women. Amid the hubbub of the crowded ship, he was lucky if he could prevent the women from smuggling liquor on board and could keep brawling to a minimum.

In 1829 the puritanical Lieutenant Robert Wauchope was appointed flag captain to Sir Patrick Campbell. Wauchope insisted that he would accept the appointment only if prostitutes were kept out of the ship. Campbell could not allow his junior to bargain over his promotion, and so he sent the impertinent young officer to appear before the Admiralty. The First Sea Lord, Admiral Thomas Hardy—who had been the boon companion of Horatio Nelson—conducted the interview. Here is a compressed version:

Hardy: I understand you object to women going on board.

Wauchope: I object to prostitutes going on board.

Hardy: You go contrary to the wishes of the Admiralty and will therefore give up your commission.

Wauchope: No. If the Admiralty choose to take my commission on this account, they may. I will not give it up.

Hardy: As one of the Lords of Admiralty, I consider it right that women should be admitted into ships; when I was at sea, I always admitted them.…

Wauchope: Sir Thomas, it is written that whoremongers shall not enter heaven. Many officers hold the same opinion about admitting women aboard as I do.

Hardy: I am sorry to hear it sir.… You have given up your commission.35

Apparently Wauchope finally agreed to give up his stand on the issue, for he received his commission, and eventually he himself rose to the rank of admiral.

THE HARD CASE OF SEAMEN’S WIVES

Seamen’s wives led a hard life. Men caught by a press gang had no time to arrange for the maintenance of their families while they were at sea. Often an impressed man simply disappeared from his wife’s life; she might not hear from him for years, even if he survived the rigors of the navy. Samuel Pepys described in his diary on 1 July 1666 the anguish of a group of women he saw at the Tower of London, where newly impressed men were collected and carried off to the navy:

To the Tower, about the business of the pressed men. But, Lord, how some poor women did cry; and in my life I never did see such natural expression of passion as I did here in some women’s bewailing themselves, and running to every parcel of men that was brought, one after another to look for their husbands, and wept over every vessel that went off, thinking they might be there and looking after the ship as far as ever they could by moonlight, that it grieved me to the heart to hear them.36

When a seaman’s ship returned to England, his wife seldom knew in advance when or where his vessel would arrive. When she did learn that her husband’s ship was in, if she was living far from his place of arrival she probably had to get there on foot, since not many wives could afford to pay for a seat on a stagecoach or coastal vessel. It was a common sight on the lonely roads of Devon and Cornwall, where so many seamen came from, to see a group of seamen’s wives and their ragged children stumbling along toward Plymouth or distant Portsmouth. West-country wives of seamen whose ships anchored at the Nore (at the mouth of the Thames) or the Downs (near the point where the North Sea meets the English Channel) found it even more difficult to get to their husbands. The prostitutes were usually well settled on the lower deck by the time the seamen’s families reached the ship. When a seaman’s wife finally got on board, there was nowhere she could be alone with her husband. She, and her children if she brought them along, had no choice but to join the raucous crowd on the lower deck.

But however unpleasant it was on board, it was important for a seaman’s wife to be present when at long last the men were paid. Unless she was there, she was unlikely to get any of her husband’s wages; the system of sending allotments to seamen’s families was inefficient at best. When payday at last arrived, the crew lined up on deck, each man holding his wide-brimmed, tarred black hat. Each man’s wages, in cash, were placed in his hat and the amount was chalked on the brim. The money was quickly spent. The purser had to be paid for the tobacco and slops (ready-made clothing) a seaman had purchased on credit from the slop chest during the voyage. A man’s accounts with the bumboat men and women also had to be paid. And if a man’s wife had not been staying on board, he probably owed money to a prostitute.37

There was very little possibility that a seaman could save any of his wages for his and his family’s future. Except for rare instances when he received a sizable amount of prize money—his share of the proceeds from the sale of a vessel and her cargo that had been captured by his ship—he lived hand to mouth.38

On the day before a ship sailed, amid the general confusion of last-minute preparations for departure, the women on board—with the exception of those few who were going to sea—bid farewell to their men, whom they might never see again. A late-eighteenth-century ballad relates:

Our ship she is all rigg’d and ready for sea, boys;

The girls that’s on board they begin to look blue;

The boats are alongside to take them on shore, boys;

Says one to the other, “Girls, what shall we do?”39

In ships sailing from the Nore or the Downs, the women often were not sent on shore until the vessel made her last call at an English port in the Channel before heading out to sea. The women then had to get home from that port as best they could. Some of the wives in chaplain Teonge’s ship in 1675 remained on board when she sailed from the Downs. They were supposed to disembark at Deal but were not sent ashore until Dover. They left in the ship’s pinnace at six in the morning, and according to Teonge, their departure was honored “with three cheers, seven guns, and our trumpets sounding.”40 Teonge was wrong about the salute; whomever it was for, it was certainly not for the women.

Starving Wives at Home

Wives of seamen struggled to keep themselves and their children from starvation while their husbands were at sea. Even if a wife had been on board on payday to get her share of her husband’s wages, the money did not last long. The government attempted to play down the plight of penniless seamen’s wives, but its efforts to repress their sad stories were not very effective.

Poor seamen’s wives were a popular subject of street ballads. Ballads, quickly composed to convey the scandals and important events of the day, were the primary source of news for the lower classes. The ballad “The Sea Martyrs,” from around 1690, for example, revealed the case of the men of H.M.S. Suffolk who were executed as mutineers for their protests over lack of pay. One verse related:

Their poor wives with care languished,

Their children cried for want of bread.

Their debts encreast, and none would more

Lend them, or let them run o’ th’ score.41

In other words, the women’s creditors refused to extend their credit. The government was so disturbed by the subversive message of “The Sea Martyrs” that a balladeer could be arrested and flogged for singing it.

From 1758 onward, legally a seaman could have an allotment of a few pence a day sent to his wife, but the system was so complicated—perhaps intentionally so—that very few seamen knew how to make the initial arrangements. In 1759, in seventy-two ships that were paid off at Plymouth, only 3 percent of the men made remittances to their families.42 It was not until 1858, at the very end of the period we are dealing with, that a workable allotment system was established.

Some officers helped their men send money home. Admiral Edward Boscawen always tried to make arrangements through private channels to enable his men to send some of their wages to their wives. In a letter from Portsmouth to his own wife, dated 26 April 1756, he wrote, “Our men have been paid, and what is very extraordinary, have paid into my hands 563 pounds, 9 shillings to send to their wives all over Britain.”43 On the whole, however, officers gave little attention to the general welfare of their men, let alone the men’s wives.

Seamen’s wives who were left behind in Portsmouth or Plymouth found it almost impossible to find work. Except for the all-male naval yards, there was little industry in either town, and very few seamen’s wives had the necessary references to be hired into domestic service, where the greatest percentage of jobs for females were to be found. They were forced to seek public charity.

Both towns were inundated with indigent seamen’s wives and children. The Guardians of the Poor, the officials in charge of public charity, were continuously struggling to keep this multitude from draining the towns’ relief funds. The Guardians’ main solution to the problem was to pack the women off to their home parishes (their birthplace or last place of residence). From 1662, when the law known as the Act of Settlement and Removal was passed, paupers (people living on public charity) who were non-residents were disposed of in this way.44

Paupers, including seamen’s wives awaiting transportation to their home parishes, were sent to the workhouse. Workhouses, paid for out of local taxes, were always underfunded and usually mismanaged. Almost without exception they were full of misery, disease, and death. Able-bodied inmates were put to work at menial jobs such as picking oakum (strands of hemp used to caulk ship’s planking) or plaiting straw for sailor’s hats, the proceeds of which went to the institution. But there were numbers of inmates who were unable to work. These unfortunates, known as the “impotent poor,” included infants, the aged, the blind, the insane, and the diseased (both chronic invalids and those with contagious diseases). Prostitutes disabled from sexually transmitted diseases often were sent to a workhouse.

All the inmates both sick and well were housed together, and, not surprisingly, the death rate was high, especially among infants. A committee appointed by the House of Commons in 1767 to examine the conditions in workhouses throughout England reported that between 1763 and 1765, of all the infants born in these institutions or who were received when under twelve months old, only seven in a hundred survived their first year.45 Some seamen’s wives became prostitutes rather than expose their children to the dangers of a workhouse.

The first workhouse in Portsmouth was founded in 1729, and by 1764 there was also a workhouse in the adjoining residential community of Portsea. In 1801 there were at least three in the Portsmouth area.46 All of them were crowded with seamen’s wives, most of them awaiting transportation to their home parishes.

Plymouth taxpayers were also burdened with the expense of sending home scores of destitute seamen’s families. There were so many of these families in Plymouth in 1758 that special legislation had to be initiated by the county to raise the funds necessary to send all of them to their home parishes.47

The first workhouse in Plymouth, established in 1708, took over from the Hospital of Poor’s Portion, a church-run almshouse founded in 1615.48 It had a terrible reputation for its harsh rules and crowded, unsanitary conditions. In 1727 a report of the Guardians of the Workhouse, in order to show that acceptable discipline was maintained, recorded the whipping of a woman and her daughter “for not performing the task set them.”49 Many of the buildings of the Poor’s Portion workhouse, constructed in 1630, continued to house inmates until 1851, when they were finally torn down, “being in a loathsome condition.”50

Seamen’s wives who tried to avoid the workhouse by begging could be arrested, jailed, and then sent to their home parishes under the vagrancy laws rather than the poor laws. Beginning in 1597 vagrants were to be whipped and imprisoned before being sent home. After 1750 female vagrants were seldom whipped, and by the late eighteenth century most vagrants were simply shipped off without being punished first.51

A seaman’s wife who turned to begging not only risked arrest, she also had to compete with the bands of skilled beggars, including disabled seamen and their women, who roamed throughout England. (Even those disabled seamen who received a pension could not survive on it alone.) In 1787 the Leeds Intelligencer reported the presence of such a band in that inland town:

Last week five or six sailors, or pretended sailors, maimed or without a leg or an arm, or both, who wander through the Kingdom with the model of a ship, living on continual vagrancy…were lodged in the House of Correction at Wakefield, in order to be sent to their several homes. Several women belonging to them disperse themselves in the daytime, begging, telling fortunes, etc. in different parts; the whole gang usually assemble together at nights…in obscure lodging houses, meeting with other idle and dangerous persons.52

A number of ballads told of the plight of disabled seamen and their wives, not always sympathetically. An example is the comic ballad “Oh! Cruel,” in which a disabled seaman’s wife describes how she and her husband are forced to beg for a living:

Oh! cruel was th’ engagement in which my true love fought,

And cruel was the cannon ball that knock’d his right eye out;

He us’d to leer and ogle me with peepers full of fun,

But now he looks askew at me, because he has but one.

Oh! cruel was the splinter to break my deary’s leg,

Now he’s obliged to fiddle, and I’m obliged to beg;

A vagabonding vagrant, and a rantipoling [whoring] wife,

We fiddle, limp, and scrape it, thro’ the ups and downs of life.53

Once a seaman’s wife arrived back in her home community, unless she had relatives to care for her or could find a job, she still was faced with the choice of prostitution, begging, or public charity. Even those wives who found factory work often lapsed into prostitution rather than continue to work ten- and twelve-hour days, six days a week for inadequate pay.

When a wife heard that her husband’s ship had again returned to an English port, the process of going to his ship and then being sent home as a pauper started all over again.

Wives Turned Prostitute (and Vice Versa)

A popular subject of eighteenth-century prints and drawings was the seaman’s prim young wife. The stereotype, still accepted today, was that a seaman’s wife was good, patient, and faithful while the seaman’s whore was bad, drunken, and dishonest. Actually, the line between wife and prostitute was thin; seamen’s wives often turned to prostitution while their husbands were at sea.

Contemporary ballads did not always make this faulty contrast between good wife and bad whore. A ballad of the late seventeenth century, “The Seamen’s Wives’ Vindication,” purports to refute the accusation that seamen’s wives are drunken and promiscuous. Actually, it reinforces the view of the wives as carousing prostitutes. The following verses are representative of the ballad’s rather muddled lyrics:

Here you have newly reported that we are girls of the game,

Who do delight to be courted. Are you not highly to blame,

Saying we often are merry, punch is the liquor we praise,

Though we are known to be weary of these our sorrowing days?

How could you say there were many wives that did drink, rant, and sing,

When I protest there’s not any of us that practice this thing?

Are we not forced to borrow, being left here without clink?

’Tis in a cup of cold sorrow if we so often do drink.54

While many seamen’s wives became seamen’s prostitutes, the reverse was also true. When a seaman came ashore at the end of his vessel’s commission, it was not unusual for him to get married to a friendly prostitute. Up to 1754, when the Marriage Act forbidding quick marriages was passed, he could do this on a sudden impulse at one of the special chapels in London, most of them in the neighborhood of the Fleet Prison, where there was no waiting period.55 (In regular churches banns had to be read for three consecutive weeks before a wedding could take place.) In 1753 the Reverend Alexander Keith, who ran a quick-marriage chapel in Mayfair, wrote down the following incident:

I was at a public-house at Radcliffe, which was then full of sailors and their girls; there was fiddling, piping, jigging, and eating; at length one of the tars starts up and says, “D——m ye, Jack, I’ll be married just now; I will have my partner, and.…” The joke took, and in less than two hours ten couple[s] set out for the Fleet. I staid [until] their return. They returned in coaches; five women in each coach; the tars some running before, others riding on the coach box; and others behind. The Cavalcade being over, the couples went up into an upper room, where they concluded the evening with great jollity. The next time I went that way, I called on my landlord and asked him concerning this marriage adventure; he first stared at me, but recollecting, he said those things were so frequent, that he hardly took any notice of them, for, added he, it is a common thing, when a fleet comes in, to have two or three hundred marriages in a week’s time among the sailors.56

SEAMEN’S PROSTITUTES ON LAND

Legal Status

Although the prostitutes of Portsmouth and Plymouth made up a considerable part of the population of those towns, they formed no cohesive group and had no political power and next to no legal rights. For that matter, few women, regardless of their social station, controlled their own lives, but respectable women were protected by their status within society. Prostitutes were particularly powerless; not only were they female and part of the great majority of the illiterate, unskilled underclass, but they lived outside the bounds of acceptable cultural standards. Prostitutes were open to ridicule and degradation and to both physical and emotional abuse that would not have been countenanced if directed toward respectable women.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries prostitution was rife in the towns and cities of England. As the country shifted from an agricultural society to a largely industrial one, great segments of the population moved from rural areas to urban centers. Many young women were uprooted from the country parishes where they had been part of a tightly knit, relatively stable community and thrown into the unfamiliar, hostile environment of city slums. These were times when most women were socially as well as financially dependent on their male family ties. A woman’s social status was related to the status of the male head of her household. A young working-class woman without a man to maintain her—father, husband, or brother—was an outcast. She had neither social nor economic stability.

Prostitution was never in itself against the law, with the exception of one two-year period from 1822 to 1824. So long as a prostitute was not unruly, she was allowed to ply her trade without official interference. There were, however, many attempts to legislate against prostitution. In 1770 Sir John Fielding, the eminent London magistrate who, with his brother Henry, the novelist and judge, organized the first London police force, attempted to get a law passed under which prostitutes could be arrested under the vagrancy laws (together with ballad singers, who also loitered on the public thoroughfares); but he was unsuccessful.57

Under the Vagrancy Act of 1822 a prostitute could be arrested as “an idle and disorderly person” simply for soliciting. The law specified, “All common prostitutes or night-walkers wandering in public streets or highways and not giving a satisfactory account of themselves are to be deemed idle and disorderly persons, and as such liable to a month’s imprisonment.”58 In 1824 another Vagrancy Act was passed that returned to the earlier practice of arresting only those “common prostitutes” who behaved in public “in a riotous or indecent manner.”59 (The term common prostitute denoted a woman whose customers shared her “in common,” as distinguished from a mistress, who was supported by one man.)

For centuries prostitution, both in naval ships and in naval ports, was intentionally ignored by the Admiralty. It was not until the late 1850s, by which time prostitutes seldom came into naval ships, that the Admiralty began to take an active role in the control of prostitution in naval ports. At that time both the navy and the army became concerned over the epidemic of venereal disease among their men. They did not, however, try to control the disease by focusing on soldiers and sailors; they focused on the single women living in the areas around army bases and naval stations. In the 1860s a series of laws were passed—called the Contagious Diseases Acts (Women), a euphemism for venereal diseases acts—that closely involved the navy and the army. In designated districts, including Portsmouth and Plymouth, plainclothes police were sent out to identify prostitutes and to place their names on an official list. Any lower-class young single woman living alone was liable to be listed as a prostitute with no way to disprove this designation. Once a woman was listed, she was forced to be examined every few weeks for sexually transmitted disease, and if found to be infected, she was sent into a hospital lock ward (a facility specifically for the treatment of venereal disease) for a period of up to nine months. The laws were repealed in 1866, after years of agitation by social reformers, who protested that the acts were prejudicial to women, as indeed they were.60

Numbers

Before the 1850s, when the navy began to take an interest in the prostitutes of Portsmouth and Plymouth, the regulation of prostitution rested solely with local authorities, who ignored the existence of these women as much as possible and took no action against them unless they were disorderly. There are therefore almost no data on the prostitutes of these naval ports. Their numbers, their average age, and their way of life on shore can only be inferred from a few random records, the passing impressions of a few individuals, and the highly colored propaganda of social reformers.

The reformers were more interested in gaining public support for their mission “to rescue fallen women” than in collecting accurate data on prostitution. In 1824, for example, a naval surgeon’s pamphlet against allowing women in naval vessels estimated that there were twenty thousand prostitutes in Portsmouth. The 1821 census puts the combined population of Portsmouth, Portsea, and Gosport at less than sixty thousand; according to the surgeon’s estimate, then, one in three people in the area would have been a prostitute.61 The figure is wildly exaggerated.

Census data, from the first census in 1801 onward, do show a preponderance of females in both Portsmouth and Plymouth, even though the main industry in each town was the dockyards, which hired at most a handful of women. In the census of 1821, for example, there were 4,798 more females than males in the combined population of Portsmouth and Portsea, even though wives of seamen and soldiers awaiting transportation to their home parishes were not counted.62

There is no record of there ever being a shortage of women to fill naval ships in Portsmouth and Plymouth, even when a whole fleet arrived. There are a number of mentions of over four hundred women coming into a single vessel, and the seaman Samuel Stokes noted in his memoirs that on one payday in 1809 the ninety-eight-gun Dreadnought, with a complement of eight hundred men, had on board “thirteen women more than the number of our ship’s company and not fifty of them married women.”63 It is apparent that more than one thousand prostitutes were always available.

Whatever the total number of prostitutes in naval ports may have been, it is unlikely that so many of them have ever been gathered together in one enclosed space at any time in history as were regularly assembled on the lower decks of vessels of the Royal Navy in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

The Prostitutes’ Way of Life

The prostitutes who lived in naval ships in port were at the very bottom of the social and economic ladder; only the most desperate woman would enter the nightmare world of the lower deck to sell her services to any man who chose her. Her partner might be anyone from a naive young boy to an “incorrigible rogue.”

At the beginning of a war, when the navy needed to raise large numbers of men in a hurry, it took in convicted rogues and vagabonds from jail. When war with France started up in 1744, an act of Parliament was passed that ordered that “any rogue or vagabond of the male sex over twelve years of age, after punishment, [was] to be employed by His Majesty’s service by sea or by land.” And again in 1756, at the beginning of the Seven Years’ War, an order was sent out “to impress loose and disorderly persons.”64

In 1795 the shortage of men was so severe that the Quota Acts were passed, which required magistrates in every county in England to provide, within a period of three weeks, a specified quota of men for the navy based on the population of the county. To fulfill these quotas, communities cleared their jails.65 Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood wrote to his sister in 1797 that “the refuse of the gallows and the parings of a gaol…make the majority of most ships’ companies in such a war as this.”66

There was a good chance that a prostitute’s partner was suffering from a sexually transmitted disease. Until 1795 a seaman had to pay the ship’s surgeon fifteen shillings—most of a month’s wages—in order to receive treatment for a venereal disease. Many, therefore, avoided treatment.67 After 1795 treatment was free, but there were no regulations to ensure regular physical examinations of seamen. In any event, the various stages of the diseases, especially syphilis, were not well understood. In fact, until 1793 syphilis and gonorrhea were generally thought to be the same disease. Treatment was not very effective. The primary remedy was mercury, applied as an ointment or ingested in the form of quicksilver as a purge—dangerous in itself.68

A prostitute, especially a ship’s prostitute, was unable to protect herself from either venereal disease or pregnancy. Some women were made sterile by gonorrhea, but for most of them, pregnancy, like infection, was a constant specter. In the 1820s and 1830s a few middle-class women used douches and vaginal sponges, with alum, bicarbonate of soda, or vinegar. These might have afforded slight protection if used immediately after coitus, but they were impossible for prostitutes to use on board ship.69 Although condoms had been used in England by upper-class men for both prophylaxis and contraception since the seventeenth century, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries they were still expensive and considered effete. They were made of lamb’s gut, cleaned and rubbed with bran and almond oil, and, when put on, secured with ribbons tied around the scrotum.70 It is impossible to imagine a tough old tar using one, even if he knew such a thing existed.

An infected ship’s prostitute found it difficult to get medical treatment. Private physicians were much too expensive, and clinics and hospitals often refused to admit women suffering from venereal disease, especially known prostitutes. In the latter part of the eighteenth century some cities set up lock wards for women, but there was none in Portsmouth until an Admiralty-sponsored one was opened in 1858. In Plymouth the first such facility, also sponsored by the Admiralty, was opened in 1863.71 Both were started after the period we are dealing with. Earlier, if a prostitute was so sick that she could not work, she usually ended up in the public workhouse as one of the unemployable “impotent poor,” where she received little or no medical treatment.

It was taken for granted by most people that sexually transmitted diseases represented the wages of sin and that the sufferers deserved what they got. Even many doctors believed that sexually transmitted diseases were caused by excessive sexual activity, Symptoms of gonorrhea in a woman were not considered to be serious and were often ignored. When treatment was provided, it was largely ineffectual and sometimes harmful, consisting of warm baths, salves, and medicines that included such dangerous ingredients as sugar of lead and vitriol.72

In addition to sexually transmitted diseases, ship’s prostitutes were victims of the other contagious diseases that afflicted naval crews. And unsanitary living conditions, on land as well as on board, combined with a bad diet and quantities of cheap gin, increased their vulnerability.

Ship’s prostitutes worked independently. They earned too little to be sponsored by the madams who ran bawdyhouses. They rented rooms in cheap lodging houses and also shared the quarters of poor families who welcomed even the small rent a ship’s prostitute could afford. Often several prostitutes shared a small room.73 In Portsmouth many of the ship’s prostitutes lived in dilapidated buildings along the congested lanes flanking High Street, or on the Point, the spit of land crisscrossed by streets full of low sailors’ taverns. Others lived in poor sections of Portsea, earlier called the Common, or across the water in Gosport.74 In Plymouth many prostitutes lived in rented rooms in the district of sailors’ taverns surrounding Castle Street near Plymouth Quay, known to seamen as Castle Rag or Damnation Alley.75 Both the Portsmouth and the Plymouth slums incubated all the ills that go with lack of sewers, tainted water, and crowded, airless living quarters.

While some ship’s prostitutes grew up in the local slums, a number came to town from the surrounding countryside, especially in times of crop failure or general economic depression. Admiral Hawker reported in the 1820s that officials in a country parish bordering on Hampshire regularly sent “young women who were likely to become burdensome…to Portsmouth, from whence they never returned.”76 In 1871 a Plymouth magistrate found that four out of five of the registered prostitutes in greater Plymouth were from the neighboring rural areas of Cornwall, and one can assume that this was the pattern earlier in the century as well.77

It appears likely that a large number of ship’s prostitutes were startlingly young. Samuel Leech, a seaman in the Anglo-American War of 1812, noted that “many of the lost unfortunate creatures” brought into his ship “were in the springtime of life,” and in that same period the seaman William Robinson referred to the prostitutes in his ship as “poor young creatures.”78 In both London and Edinburgh, where, unlike Portsmouth and Plymouth, a good deal of information about prostitutes was gathered, many prostitutes were little more than adolescents. In the 1750s the magistrate John Fielding said that most of the inmates of London brothels were under eighteen and many no older than twelve.79 A London relief organization reported in 1813, “The number of abandoned children from the age of twelve to fourteen years living in a state of prostitution who are brought daily before the magistrates for petty crimes, are increased to an alarming degree within these few years.”80 And William Tait, house surgeon at the lock hospital in Edinburgh, found that between 1835 and 1839, of the one thousand prostitutes admitted, half were between the ages of fifteen and twenty, forty-two were under fifteen, and one was nine.81

At a time when factories hired children of six or seven to work a ten- or twelve-hour day, and warships carried midshipmen of ten or eleven as well as a number of adolescent boys in the crew, it is not surprising to find that officers and seamen alike accepted the fact that very young prostitutes came on board. It was not until 1861 that legislation was passed against the use of girls under twelve for immoral purposes. The age of consent (to sexual congress) for females was twelve throughout the period we are dealing with. In 1871 it was raised to thirteen, not a great step forward, and in 1885, to sixteen.82

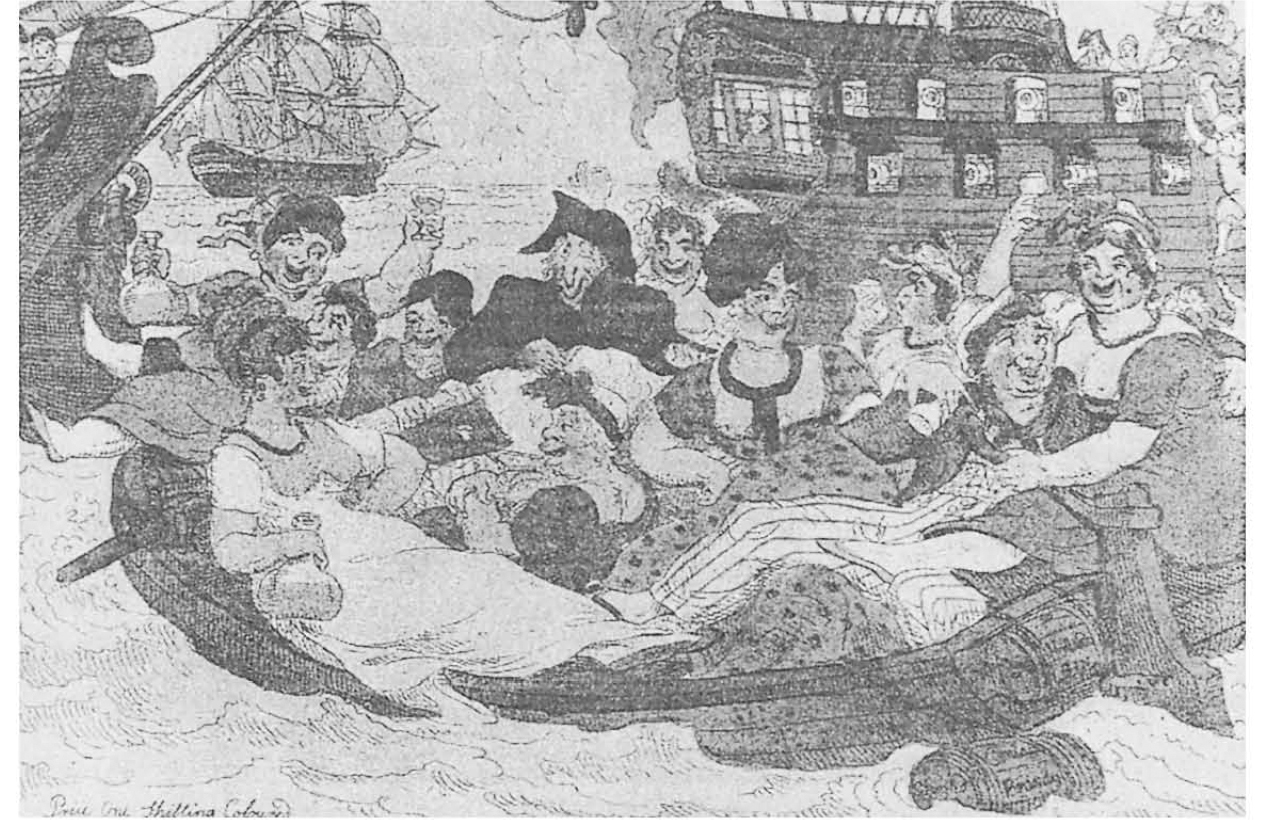

The prostitutes of Portsmouth and Plymouth were a popular subject of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century prints and watercolors by such well-known artists as George Cruikshank and Thomas Rowlandson. Almost all of these illustrations present the popular stereotype of the prostitute: large, muscular, buxom women in their thirties or forties, with coarse features and leering expressions. These caricatures bear little resemblance to the undersized, often sickly teenagers who actually served the seamen.

The same stereotype is found in written portrayals of prostitutes. Dr. George Pinckard’s description of “Portsmouth Polls,” in 1795, is typical of the genre:

To form to yourself an idea of these tender, languishing nymphs, these lovely, fighting ornaments of the fair sex, imagine a something of more than Amazonian stature, having a crimson countenance, emblazoned with all the effrontery of Cyprian confidence and broad Bacchanalian folly; give to her bold countenance the warlike features of two wounded cheeks, a tumid nose, scarred and battered brows, and a pair of blackened eyes, with balls of red; then add to her sides a pair of brawny arms, fit to encounter a Colossus, and set her upon two ankles like the fixed supporters of a gate. Afterwards, by way of apparel, put upon her a loose flying cap, a man’s black hat, a torn neckerchief, stone rings on her fingers, and a dirty white, or tawdry flowered gown, with short apron, and a pink petticoat; and thus will you have something very like the figure of a “Portsmouth Poll.”83

A very different picture is presented in the only actual firsthand report I have found about an individual ship’s prostitute. It comes from the journal of Robert Mercer Wilson, a seaman in H.M.S. Unité from 1805 to 1809:

A good-looking young woman was taken in [the vessel] one day by a messmate of mine. When he brought her below, I observed that in spite of her trying to be cheerful, she was sad and many a sigh escaped her.… My thoughtless messmates…were more mindful of pleasure than noticing whether their girls were glad or sad.… For my part I observed her sighs, and from her discourse I found her to be a woman of some learning.…

I leave my readers to guess how I was surprised and amazed when I perceived her to be big with child. “Good God!” said I to myself, “well might she sigh and look sad.” What had hindered myself and my messmates from observing it before was she had so artfully concealed it…that it was impossible to perceive it till she took off her cloak.…

In spite of my remonstrances with my messmate not to have any connections with her, my offering to take her off his hands, which made him think I was anxious to possess her charms, made him the more determined to satisfy his ———.

Poor girl! It was a dear bought pleasure for her, for next morning she was seized with convulsions severe, which indicated the quick birth of the infant in her womb. When her situation was made known, our First and Second Lieutenants (to their honour be it said) gave her a guinea each; I contributed a small matter, but not half so much as I could wish, and she went on shore.

The next day a letter came from her (though not written by her) to this effect; “that she [had] scarcely arrived on shore before she was delivered of a fine boy, in a promising state.” She desired her compliments to me, and I wrote her an answer back. I must confess, only for the esteem I bore for the girl I loved, my heart might have been smitten with the charms of that unfortunate fair one, so prepossessed was I in her favour. To conclude, I had afterwards the pleasure to hear that all went well with her, and she expected soon to join her friends, who had received her into their good graces.84

THE REFORM MOVEMENT AND THE PROSTITUTES

Private Efforts

Beginning around 1750 a long period of social reform began. It started in London and soon spread throughout Great Britain. Close to a hundred organizations and societies, financed totally by private funds, were formed to address every imaginable social evil from the slave trade and the plight of “climbing boys” (chimney sweeps) to the salvation of prostitutes.

The spirit of reform even penetrated the upper echelons of the navy, a bastion of conservatism. A number of naval officers became actively involved in seeking reform in the navy itself. Among the noted admirals who were active in the reform movement was Richard Kempenfelt, who, when his flagship the Royal George sank in 1782, had on board, in addition to four hundred prostitutes, four hundred Bibles—the first allotment of Bibles donated for the uplift of seamen by the Naval and Military Bible Society.85 (Admiral Kempenfelt, the prostitutes, and the Bibles were lost.) Another Evangelical admiral, whom we have already mentioned, was Lord (James) Gambier, known throughout the navy as Preaching Jemmy. Still others were Baron de Saumarez (James Saumarez), Viscount Exmouth (Edward Pellew), and Lord Barham (Charles Middleton), first lord of the Admiralty.

How effective the reformers were, both inside and outside the navy, in their campaign against prostitution is open to question. They focused on moral uplift rather than on improving the economic conditions that engendered prostitution; their aim was to rid the nation of vice, not to alter the economic status quo or the class system. These middle-class reformers were strongly opposed to radical social thought such as that of Tom Paine and to political action by the poor themselves. The reformers talked a great deal about the importance of “fidelity” among the lower classes, by which they meant fidelity to the standards set by the upper classes. They also firmly believed that immorality promoted social dissolution.

We tend to think that sentimentality and condescension were the special province of the Victorians, but eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century reformers were also restricted by narrow, class-bound, pious, and sentimental attitudes. They, like the Victorians who followed them, were diligent in their efforts to rescue the “deserving poor” and “repentant prostitutes”; the undeserving and the unrepentant could go hang—and often did, in a period when even petty theft was a capital offense.

A sampling of the names of institutions formed “to rescue” indigent young girls and prostitutes reveals the bias of the reformers: the Asylum for Poor, Friendless, Deserted Girls under Twelve Years of Age (founded 1758); the Lock Asylum for the Reception of Penitent Females (1787); the Friendly Female Society for the Relief of Poor, Infirm, Aged Widows and Single Women of Good Character Who Have Seen Better Days (1802); the euphoniously named Forlorn Female’s Fund of Mercy for the Employment of Destitute and Forlorn Females (1812); and the Maritime Female Penitent Refuge for Poor Degraded Females (1829). There were also the Institution for the Protection of Young Country Girls (1801) and, for the girls who escaped the net of those protectors, the Society for Returning Young Women to Their Friends in the Country (founding date unknown).86

A representative example of institutions devoted to the uplift of fallen women was the Female Penitentiary for Penitent Prostitutes, founded in 1808 in Stonehouse and later moved to Plymouth.87 (The three towns that made up greater Plymouth were Plymouth Dock, called Devonport after 1824, Stonehouse, and Plymouth.) The penitentiary was built with private money after investigations revealed the crowded, filthy conditions in the Poor’s Portion Workhouse. While the penitentiary was well organized and clean, it was a grim and repressive institution. Newly admitted women were placed in solitary confinement to contemplate their past sins until it was determined that they would not pollute the attitude of the other inmates, who presumably had rejected forever “their lives of shame.” Inmates were dressed in drab uniforms, and their heads were shaved to humble their pride in their physical appeal. They were forced into a rigid daily routine in which every hour was accounted for, beginning with prayers at dawn followed by ten or twelve hours of work. The aim of the institution was to teach the inmates a useful skill so that they would be able to find respectable work when they were released. In practice the penitents toiled at the same boring unskilled jobs, such as scrubbing other people’s laundry, that workhouse residents performed and that did nothing to improve possibilities for future employment. Most of the penitentiary inmates ran away. The few who were released into respectable jobs were hired as domestic servants, and since it seems likely that many of them had worked as housemaids before they turned to prostitution, this supposed salvation merely put them back where they had started. Data gathered in the 1870s in London showed that 82 percent of the prostitutes in institutions run by the Rescue Society had formerly been house servants, and since by far the greatest number of jobs available to women in Plymouth were in domestic service, a similar pattern was no doubt evident at the Plymouth Penitentiary for Penitent Prostitutes earlier in the century.88

Although the reform movement aided some destitute girls and women and eventually led to greater legal protection of young girls against sexual exploitation, the effectiveness of these many institutions was slight, considering the great effort exerted. The reformer James Beard Talbot stated that in the seventy-seven years between 1758 and 1844 not more than fifteen thousand women in London received aid from the organizations set up to help and reform prostitutes, an average of two hundred a year.89 That is a very small number compared with the thousands of women each year who were living by prostitution. Nonetheless, we should not be too quick to dismiss the efforts of these middle-class reformers who at least attempted to aid the indigent. Most of their middle-class contemporaries were concerned only with seeing to it that the poor did not infringe on their own comfortable lives. As for the gentry, with very few exceptions they dismissed as unimportant the problems of all those who were not of their own kind.

The Reform Campaign within the Navy

In the relatively peaceful period of the 1820s following the close of the American Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, several naval officers began a campaign to get the prostitutes out of naval ships, and for the first time the general public was made aware of the situation on board naval vessels in port.

The Evangelical Admiral Edward Hawker attempted to get the navy to enforce a ban against accepting prostitutes on board naval vessels, but he met with no success. When he found that the Admiralty “did not want to take any decided measures on the subject,” he decided to go public.90 In 1821 he published an anonymous pamphlet entitled A Statement Respecting the Prevalence of Certain Immoral Practices in His Majesty’s Navy that described in vivid terms the scenes on board ships full of prostitutes. Although it was addressed to the Admiralty, it was distributed widely. It begins:

It has become an established practice in the British navy to admit, and even to invite, on board our ships of war, immediately on their arrival in port, as many prostitutes as the men, and, in many cases, the officers, may choose to entertain,…all of whom remain on board, domesticated with the ship’s company, men and boys, until they again put to sea. The tendency of this practice is to render a ship of war, while in port, a continual scene of riot and disorder, of obscenity and blasphemy, of drunkenness, lewdness, and debauchery.91

The pamphlet goes on to point out the hypocrisy of the navy and even the king in professing to fight immorality while continuing to allow “practices at once so profligate, disgraceful, and destructive.” It continues:

There is something in the idea of being humbugged, to use a vulgar but significant expression.… What can more wear the air of an attempt of this revolting description than to publish Rules and Regulations, and to issue Royal Proclamations for restraining vice and immorality, and to issue sums of money and institute societies for the distribution of Bibles and Prayerbooks among our seamen, and even appoint chaplains to preach to them, and yet after having done all this, to permit and even sanction the practices which…convert our ships of war into brothels of the very worst description.92

Hawker even brought up the taboo subject of buggery, or sodomy, among naval crews. (The term homosexuality did not exist.) Although fear of an increase in homosexual activity among naval crews was a prime reason for allowing prostitutes on board, officers avoided the very mention of the subject. Sodomy was one of the few capital offenses in the Royal Navy. Not many cases, however, were brought before naval courts. Officers ignored homosexual incidents among their crews if they could.93 The very word sodomy was such an embarrassment that even in court-martial records, euphe-misms such as “unclean acts” and “crimes against nature” were used.

Hawker, in his efforts to refute all the arguments that could be made in defense of having women on board, argued that the presence of the prostitutes actually encouraged “unnatural crimes” (homosexual acts). “It is,” he said, “when a familiarity with gross pollution has prepared the mind for further grossnesses that such enormities [as sodomy] are to be apprehended.”94

While Hawker provided pages and pages of arguments against allowing prostitutes on board, he scarcely mentioned how the ancient tradition could safely be canceled. His only reference to the need for regular shore leave was presented almost as an aside, in this one sentence: “If reasonable permission were given them (the seamen) to go on shore when circumstances would admit to it, the sailors, grateful for the indulgence, would be more disposed to return to their ships than they are at present.”95

Admiral Hawker’s diatribe reveals the prejudices of gentlemen of his day. He was shocked that surgeon’s mates on some ships were “forced to submit to the indignity” of examining for venereal disease the women coming on board; any indignity to the women was below Hawker’s notice. While dismissing the feelings of the women of the lower deck, he was solicitous toward officers’ wives. He reported the following incident as an example of the way the presence of prostitutes affected the sensibility of a captain’s wife: “In a case that has lately occurred, the captain and his wife were actually on the quarterdeck on a Sunday morning while seventy-eight prostitutes were undergoing an inspection of the first lieutenant to ascertain that their dress was clean.”96

Hawker’s anonymous pamphlet caused a sensation, and it almost immediately went into a second printing. The most clear-headed response to its charges came from Captain Anselm Griffiths, who countered Hawker’s dramatic outcry with a more temperate approach to the problem of ridding naval ships of prostitutes. In his book on naval economy, published in 1824, Griffiths cautioned that “you cannot make men moral by mere force of authority,” and he maintained that women should be banned only if the seamen were given “every liberal indulgence of leave on shore.” He pointed out that “the admission of two or three hundred profligate women into the confined space of a ship’s between-decks is bad,” but since shore leave is denied, “it is a sort of necessity,” and “it has to plead long, very long, prescriptive custom.” He was even sympathetic toward the prostitutes. “Generally speaking those women do,” he wrote, “preserve as fair a portion of decency as you can expect.”97

Griffiths also disagreed with Hawker regarding the problem of homosexuality in naval crews. It was Griffiths’s belief that lack of women did increase cases of sodomy. He pointed out that “during the late war the crime [of sodomy] increased to a most alarming extent,” and he suggested that this was due to “the very lengthened periods at sea and the consequent absence of female society.”98

The first step in abolishing prostitution on board, Griffiths wrote, should be to deny any officer, whether admiral, captain, or lieutenant, the privilege of bringing a woman on board.99 This was a most unpopular suggestion among most of his fellow officers. Even those who did not bring their own women on board disapproved of any official restrictions on their freedom.

As a result of the reformers’ efforts, the subject of prostitutes in naval ships received a great deal of public attention, but neither Parliament nor the Admiralty took any action on the matter, and the public’s interest in the subject soon waned.

THE PROSTITUTES RETREAT TO SHORE

The gradual withdrawal of prostitutes from the ships of the Royal Navy was primarily due, not to the reformers’ campaign, but to a series of improvements in naval life. These improvements resulted in a drop in desertions that in turn led to greater willingness among officers to give shore leave.

Following the close of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, the number of seamen was greatly reduced, and it was no longer necessary to use press gangs to fill naval crews. With the demise of impressment, a major cause of desertion was gone, and in a much smaller navy made up of volunteers, captains began to lose their dread of giving shore leave.

By 1826 specific regulations had been established for maintaining clean, ventilated, dry living quarters, and for providing fresh meat and vegetables to naval crews as well as tea and cocoa.100 With the increase of regular physical examinations and the steady improvement of medical care, the incidence of disease was greatly reduced. Discipline became less harsh and less arbitrary. Pay gradually increased, wages were paid more promptly, and there were more opportunities for advancement. In the 1850s a workable allotment system was instituted.101

Ironclad steamships gradually replaced wooden sailing ships—the Battle of Navarino in 1827 was the last great battle fought under sail—and life on board steamships was much less harsh than it had been within the old “wooden walls.” Conditions were also much less crowded; wind-driven ships had needed a great number of men to work the sails. While sailing ships could remain at sea for months, steamships had to come into port regularly in order to refuel. This meant that food and water were replenished more frequently, and there were more opportunities for shore leave. Furthermore, since steamships required crews who were trained in technical skills, it was expedient for the navy to improve living conditions and provide better benefits so that men would continue in its service for an extended time after they had been trained for specific skilled jobs. In 1853 the old system of hire and discharge, under which crews were signed up for a single commission only, was replaced by a continuous-service policy. The new policy fostered consistent regulations throughout the navy, in contrast to the former situation in which each vessel’s captain had control over his men’s lives.

All these changes made for happier, better-disciplined crews whose officers could trust them not to run away when they were allowed to go on shore.

With the drop in desertions and the increase of leave, the long tradition of allowing crowds of women on board faded away. By the 1840s most captains were giving shore leave in home ports, so that crowds of prostitutes seldom came into vessels in English harbors. By the 1850s, even in foreign ports, the practice had become rare.

It was during the 1840s that the following apocryphal story was widely circulated in the navy. When the crew of one of the ships lying at Portsmouth threatened to mutiny because the captain refused to allow women on board, the port admiral signaled the captain of a ship full of prostitutes to send two hundred of the women over to the troubled vessel. He did so, and the mutiny was quelled.102 This fictitious anecdote was a joke that could only be made at a time when the old tradition had faded. During the 150 years when it was accepted that Royal Navy ships in harbor would be full of prostitutes, the story would have amused neither the officers nor the seamen themselves.