![]()

Women of the Lower Deck at Sea

British women served at the same guns with their husbands, and during a contest of many hours, never shrank from danger, but animated all around them.

—Admiral Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth, reporting on the Battle of Algiers

NOT ALL THE WOMEN living in naval vessels disembarked when the crowds of prostitutes were sent ashore shortly before the ships sailed. From the late seventeenth century until the middle of the nineteenth, it was customary for wives of warrant officers to go to sea. A warrant officer was assigned to a particular ship “in constant employ,” unlike both commissioned officers and seamen, who were signed onto a vessel only for a single commission, and who were often transferred to another ship before the commission was completed. A warrant officer and his wife might continue to live in a ship even when she was taken out of commission.

The wives of the ancient triumvirate of warrant officers—the boatswain, the gunner, and the carpenter—went to sea as a matter of course. So did wives of the purser and the master, who associated with the commissioned officers on the quarterdeck, as well as those of lower rank: the cooper, the sailmaker, and the cook. Petty officers—men who were selected from among the able seamen to direct the less skilled—and a few seamen, usually experienced men who made the navy their career, also sometimes brought their wives to sea.

Very few of the prostitutes who lived on the lower deck in port remained on board when the vessels sailed for foreign stations. A prostitute had little hope of earning money at sea; the men would have spent most of their pay before they sailed from England and would not be paid until they returned. A prostitute “common to the ship’s company” had a hard time at sea; a woman was dependent on a man to share his hammock and his food ration with her and to act as her protector.1

Most of the women who joined their husbands or sweethearts at sea knew before they went that life on board would be both tedious and perilous, and they realized that they might be away from home for years. Looking back at these women from a modern viewpoint, it is tempting to decide that they went to sea because they wished to find adventure. This was seldom their motivation. The evidence is that wives went to sea because they did not want to be separated from their spouses. Women who joined naval crews disguised as men were often seeking a broader experience than society allowed them on shore. Seagoing wives, on the other hand, did not set out to break social taboos. They were, in fact, behaving as a good wife was supposed to behave: cleaving to her husband and serving as his helpmate, no matter where that took her.

Officially, the women living on the lower deck did not exist. Even when a woman died at sea, the fact was seldom recorded. Their names were not listed in ships’ muster books, and since only those people who were mustered had any official existence, women were not paid and not victualed. Wives had to share their husbands’ food ration, and so did any children with them. In contrast, soldiers’ wives who traveled with their husbands were victualed at two-thirds the men’s ration, and their children got half a ration. This meant that in a ship carrying both seamen’s and soldiers’ wives, the soldiers’ wives, who were merely passengers, were given food while the seamen’s wives, who were an integral part of the ship’s company, got nothing.

THE TRADITION OF WOMEN GOING TO SEA

Women in the King’s Ships in the Middle Ages

There is a long history of women going to sea in the king’s or queen’s ships. In the Middle Ages, when voyages were brief, many of them were prostitutes.

Thomas Walsingham, a fourteenth-century priest, noted in his history of England, the Historia brevis, that a number of prostitutes were taken to sea when a fleet under the earl of Buckingham and the duke of Brittany set out on 8 November 1377 to attack the Spanish fleet. On 11 November many of the smaller ships foundered in a gale, and their people had to be transferred to the larger vessels. The remains of the fleet limped back to port for repairs, then set out again with the prostitutes still on board. After searching futilely for the enemy up and down the channel, the English finally met the Spanish fleet off Brest. Buckingham captured eight ships, but the rest of the Spaniards escaped, and the battle was considered a failure. More bad weather was met with, and it was after Christmas when the fleet finally got back home. According to the pious Walsingham, the failure and ordeals of the expedition were God’s retribution against the sailors for having taken “public women” to sea with them.2

The remarkable number of sixty women were on board Sir John Arundel’s ships when they set out from Southampton in December 1379 to go to the aid of the duke of Brittany, then fighting in Brittany. Some of the women went willingly—they were probably prostitutes—but the rest were “married women, widows, and young ladies of rank” who were kidnapped from an abbey near Southampton where many of Arundel’s men had been quartered while the fleet waited for the weather to improve. At length Arundel grew so impatient to be off that even though a new storm was brewing, he gave orders to sail. A gale struck the ships off the coast of Cornwall, and it seemed that the whole fleet would be wrecked. As the wind continued to mount, the terrified men became convinced that the storm was a supernatural one, caused by the presence of the women. According to a long-held superstition, even one woman at sea could bring forth a fatal storm, and they had sixty with them. All sixty women were thrown overboard.3 The remedy failed. The storm continued to threaten the fleet, and twenty-five of Arundel’s ships were wrecked on islands off the Irish coast. Most of the men, including Arundel and Rust, died.

Women in Naval Ships in the Seventeenth Century

By the seventeenth century the tradition of seagoing wives was well established. Phineas Pett, famous master shipwright and naval commissioner, reporting on the wreck of the Anne Royal on 10 April 1637, noted that among the people drowned were the master’s wife and another woman, and there is no indication that Pett found it unusual that the women had been on board.4

In 1674 a naval captain got into trouble as a result of having women in his ship, but only because they were costing the government money. In that year a government informer named Jones notified the Admiralty that the captain of the Ruby had listed two seamen’s wives in his ship’s muster book under male names so that he himself could pocket their pay. Jones also reported that the captain of the Thomas and Francis had collected the pay of a “Mr. Bromley” who was in fact the captain’s dog.5 So far as the navy was concerned, the women and the dog were in the same category. One is reminded of Horatio Nelson’s memorandum announcing that before he sailed he was determined to rid his ship “of all the women, dogs, and pigeons.”6

Admiralty Regulations

The Admiralty’s first printed Regulations and Instructions, issued in 1731, stated,” [A captain] is not to carry any women to sea…without orders from the Admiralty.” Later editions of the Regulations reiterated this order, with the added proviso that permission could be granted by an admiral without Admiralty approval.7 While official permission was often granted for captains’ wives and other “ladies” to live in the officers’ quarters of ships at sea, instances of warrant officers’ or seamen’s wives being authorized to go to sea were few and far between. They did occur, however.

In 1819, when the duke and duchess of Clarence and the two Ladies Fitz-Clarence were preparing to embark for Antwerp in His Majesty’s Yacht Royal Sovereign, the Admiralty ordered that “a respectable woman, sufficiently used to the sea,” should be hired to attend the ladies and should be entered on the books as an able seaman. A Mrs. Davis, the wife of a Greenwich Hospital pensioner, carried out the assignment.8

The Royal Navy operated as much by unwritten tradition as by written regulations, and the tradition of taking women to sea was firmly established by the eighteenth century. Even the sparse instructions given in the Regulations and Instructions were often ignored. Captains were given a great deal of latitude in running their ships according to their own rules, and while they grumbled about the women of the lower deck, most of them accepted the women’s presence as inevitable and simply carried on as though the women did not exist.

The Admiralty did the same. Only when it was officially informed of a women’s presence in a ship at sea did it take action. The navy was forced to take notice when evidence was presented in the court-martial of Captain Marriot Arbuthnot of the Guarland on 13 March 1755 that he had carried the wives of the master and boatswain to sea, and he was reprimanded, but this infringement of the regulations would have passed unnoticed if it had not been mentioned in the testimony given before the court.9

One of the few admirals who flatly refused to allow women in his ships at sea was Cuthbert Collingwood. He was so opposed to the practice that were it not for his reputation as a pragmatist, one might suspect him of believing that women at sea were bad luck. In 1808, when he heard there was a woman on board the Pickle, he sent an order to Rear Admiral Purvis: “I never knew a woman brought to sea in a ship that some mischief did not befall the vessel. If she did not go home [to England] with the lieutenant, pray send her out of the fleet in the first transport or merchant ship going home. She must pay her passage.”10

The following year Collingwood was greatly dismayed when he found women in his own flagship. He later explained: “Captain Carden had given permission for a number of women to come in this ship [the Ville de Paris]. I have reproved him for this irregularity and considering the mischief they never fail to create wherever they are, I have ordered them all on board the Ocean to be conveyed to England again.”11

THE DAILY ROUTINE OF WIVES AT SEA

Seamen and their wives had neither privacy nor quiet on board. They shared one hammock squeezed among hundreds of others in the great open space of the lower deck. At sea there was slightly more space for sleeping than there was in port when the fourteen to sixteen inches allowed each hammock was occupied throughout the night. At sea the hammocks of the men standing watch were empty part of the night, allowing their neighbors more room. A third or more of the men, however, did not stand watch; the “idlers” slept through the night unless all hands were called. (The term idler was applied to the men who did not keep watches but assisted the carpenter or the sailmaker or worked in the hold or did numerous other jobs during the day; they were far from idle.)12

Warrant officers’ wives had a little more privacy than seamen’s wives, since they shared their husbands’ small canvas-sided cabins located on the sides of the lower deck. In some vessels the cabins of the gunner and boatswain were on the orlop deck, below the lower deck. The orlop was the lowest deck, below the water line, where the surgeon’s quarters and the storerooms were. It was even darker and more oppressive there, but quieter than among the hordes crowded together on the lower deck.

The nightly routine of everyone on board revolved around the system of dividing the crew into two alternating watches. Each watch was four hours long. One watch slept from 8:00 P.M. until midnight, when they rose and went on deck and the men of the other watch turned in. At four in the morning there was another scramble as the sleeping men were awakened and made their way through the dark to their stations.13 And if there was a sudden shift in the wind or another crisis, all hands were called. Even the women’s sleep was never sustained.

By around 8:00 A.M. the whole ship was up, all hammocks were stowed away, and every man went to his assigned task. All the men were busy from early in the morning until late afternoon, except for the times allotted for breakfast and for the midday issue of grog followed by dinner. The only task of the wives was to keep out of the way of the work going on throughout the ship.

Warrant officers’ wives were better off than the wives of the seamen in many ways; they not only had a cabin to retire to, and could even have some of their own furniture with them, but they also were more likely to know how to read and write than seamen’s wives and so could pass long days in writing letters and reading. (Their husbands had to be literate in order to keep records of the supplies they were in charge of.) There were few books available, however; books were expensive, and there was little space for storing them. During the nineteenth century, Evangelical captains provided the men with Bibles and religious tracts, but even these were lacking in earlier times.

Warrant officers’ wives enjoyed the services of one or two servants who polished shoes, ran errands, and prepared special dishes. Most of the servants were boys, often only eleven or twelve years old. A warrant officer’s wife often formed a close maternal relationship with the child assigned to her husband. The wife of William Richardson, the gunner of the fifty-four-gun Tromp, grew very fond of her husband’s servant, a young boy who was assigned to Richardson after he was found stowed away following the Tromp’s visit to Madeira in 1800 on her way to the West Indies. Mrs. Richardson and the boy were both heartbroken when later he was transferred to the fleet’s flagship to serve as one of the admiral’s servants.14

A seaman’s wife had no place of her own, and the only personal belongings she had with her were the few things she could store in her husband’s sea chest. Wives spent their days in small groups, sometimes on the relatively quiet orlop deck or, in cold weather, near the galley on the lower deck, where the stove provided the only heat in the ship. They might do some sewing, although the men themselves were skilled at making their own clothes.

Some seamen’s wives, when they got the chance, obtained a tub of water and did some laundry, not only for their husbands but for other seamen willing to pay a few pence for the service. At sea, where drinking water was in short supply, laundry was supposed to be done in salt water, which meant that the clothes never quite dried—a problem that contributed to the men’s discomfort and rheumatic ills. Whenever they dared, the women washed with some of the supply of fresh water (a misnomer; it was always rank). Admiral John Jervis, earl of St. Vincent, was obsessed with the idea that the women in his fleet squandered the drinking water. He waged a long but futile campaign against the women who, he said, “still infest His Majesty’s ships in great numbers, and who will have water to wash, that they and their reputed husbands may get drunk on the earnings.”15

On 14 July 1796 Jervis circulated the following peevish memorandum to his captains from H.M.S. Victory, at sea. In one remarkably long sentence he cautioned:

There being reason to apprehend that a number of women have been clandestinely brought from England in several ships,…the respective captains are required by the admiral to admonish those ladies upon the waste of water and other disorders committed by them, and to make known to all that on the first proof of water being obtained for washing, from the scuttlebutt [a cask of drinking water placed on deck for the use of the crew] or otherwise, under false pretences, in any ship, every woman in the fleet who has not been admitted under the authority of the Admiralty or the commander-in-chief will be shipped for England by the first convoy.16

The order was ignored. A year elapsed, and still Jervis fretted about the women wasting water. On 21 June 1797 he sent another memorandum to his captains in which he announced, in another long grandiloquent sentence, that the future of England rested on whether or not the women could be prevented from using drinking water to wash clothes:

Observing as I do with the deepest concern the great deficiency of water in several ships of the squadron, which cannot have happened without waste by collusion, and the service of our king and country requiring that the blockade of Cadiz, on which depends a speedy and honourable peace, should be continued, an event impracticable without the strictest economy in the expenditure of water, it will become my indispensable duty to land all the women in the squadron at Gibraltar, unless this alarming evil is not immediately corrected.17

Rear Admiral Nelson, serving in the Theseus under Jervis, was on friendly enough terms with his superior to dare to suggest that Jervis would be wise to temper his anger. Nelson responded to Jervis’s memorandum the same day:

The history of women was brought forward I remember in the channel fleet last war. I know not if your ship was an exception, but I will venture to say not an Honourable [a captain] but had plenty of them, and they always will do as they please. Orders are not for them—at least I never yet knew one who obeyed.18

Nelson did not mention the possibility that sending the wives home might inflame the seamen; there was currently disaffection throughout the navy. The mutiny at Spithead had been resolved only in May, and the mutiny at the Nore had ended only the previous week. Apparently Jervis accepted Nelson’s admonition and did not carry out his threat to send the women off.

While most commissioned officers disliked having lower-deck women in their ships at sea, they enjoyed having “ladies of quality” traveling in the officers’ quarters. Jervis and Nelson were no exception. At the same time that Jervis sent off his complaining memorandum of 14 July 1796, he was enjoying the company of the socially prominent Mr. and Mrs. Wynne and their four daughters, who lived for several months in the ships of his fleet after being evacuated from Leghorn at the approach of Napoleon’s army. Jervis was especially fond of the pretty teenagers Betsey and Jenny Wynne. He nicknamed them the Admirables, and he and his officers entertained them at a round of dinner parties and dances. Jervis also promoted the engagement of Betsey to one of his captains, Thomas Fremantle.19

After Betsey Wynne married Fremantle she lived on board her husband’s ship in Nelson’s squadron with the full approval of Nelson. Nelson also took Lord and Lady Hamilton on a cruise in the spring of 1801 in the Foudroyant from Palermo to Syracuse and Malta and back. It was during this pleasant interlude that Horatia, the daughter of Emma Hamilton and Nelson, was conceived. (The cruise was made between 23 April and 30 May 1801; Horatia was born sometime between 29 January and 5 February 1802.)20

Meals on the Lower Deck

A seaman’s wife joined her husband and his messmates on the lower deck for all meals. Each mess contained some six to eight men who ate from a common pot at a table suspended from the rafters in a space against the side of the ship between two guns. The food was usually plentiful but monotonous, consisting primarily of boiled salt meat, hard biscuits, and dried peas, varying little from meal to meal. There was no coffee, tea, or hot chocolate served, which would have been a comfort in cold weather in the unheated ship. In most vessels breakfast was at eight, two hours after the hammocks had been stowed and the men had scrubbed the decks. Half the grog ration was served before dinner at noon, and the other half before supper at five.

The men themselves selected who would join their mess, and messmates were bonded together, sharing their free time and defending one another against outsiders. It is somewhat surprising that these tightly knit groups accepted a woman among them, but there is no indication that a seaman’s wife was not welcomed. Mary Lacy, who served in the navy as William Chandler, described convivial meals in her mess on board the Royal Sovereign in 1760, which included the female companion of one of the seamen.21

Warrant officers’ wives ate better than the seamen’s wives. Wives of warrant officers of wardroom rank—the master, the purser, the chaplain, and the surgeon—ate with the commissioned officers, sharing their delicacies and good wine. The boatswain, the carpenter, and the gunner and their wives ate separately from the seamen, and they too often supplemented ship’s rations with fresh meat and wine, tea, and coffee. The gunner William Richardson and his wife brought several pigs on board on their passage home from the West Indies, and they shared the last of the roast pork with other warrant officers, and with “the poor women” (soldiers’ wives) as well as an army sergeant. (Richardson charged the latter for his portion.)22

Recreation and Entertainment

Each day in the late afternoon, captains allowed their men time to relax. In good weather, wives joined the seamen on the open main deck to dance and “to skylark” (to indulge in horseplay and active games such as “follow my leader”). They danced to the music of the ship’s fiddler or were accompanied by another instrument; bagpipes were popular.23 In heavy weather, however, the women were constrained to the lower deck, where, with the gunports closed, the only light and air came from the main hatchway. While the men got fresh air working in the rigging and on the main deck, the women spent most of their time below in the odoriferous dark.

Wives also participated in the plays that crews organized and performed for their officers. Early in 1813, when Britain was at war with both the United States and France, the American diplomat Mordecai Noah witnessed such a production on board the seventy-four-gun Bulwark, flagship of Rear Admiral Philip Charles Durham on blockade off Rochefort. Noah had been on his way to his post as United States consul at Tunis, by way of France, when the American merchant schooner he was traveling in was captured by the English frigate Briton, Captain Thomas Staines, one of the ships in Durham’s fleet, and Noah was taken prisoner. His was not an onerous incarceration. Sir Thomas treated him as an honored guest, showed him around the Briton, and gave him the use of his own library. Admiral Durham invited Noah to visit the Bulwark for dinner, and a five-act play entitled “Wild Oats” was performed by the crew, followed by a group of seamen dancing the hornpipe, accompanied by the ship’s band. The play was well acted, and the scenery included “drop curtains, stage doors with knockers, footlights, and all the paraphernalia necessary to a well-organized and well-governed stage.” But for Noah the high point of the entertainment was watching one particular dancer, “an interesting figure, tastefully dressed, and moving on the light fantastic toe with much ease and agility.” Noah later reported in his journal the admiral’s comment to him:

“Don’t stare so,” said the admiral, “it is a real woman, the wife of a foretop man. We are compelled in a fleet to have a few women to wash and mend, etc.”

The sight of a real woman, as the admiral called her, was refreshing after a long voyage, particularly as the female parts in “Wild Oats” were awkwardly sustained by men.24

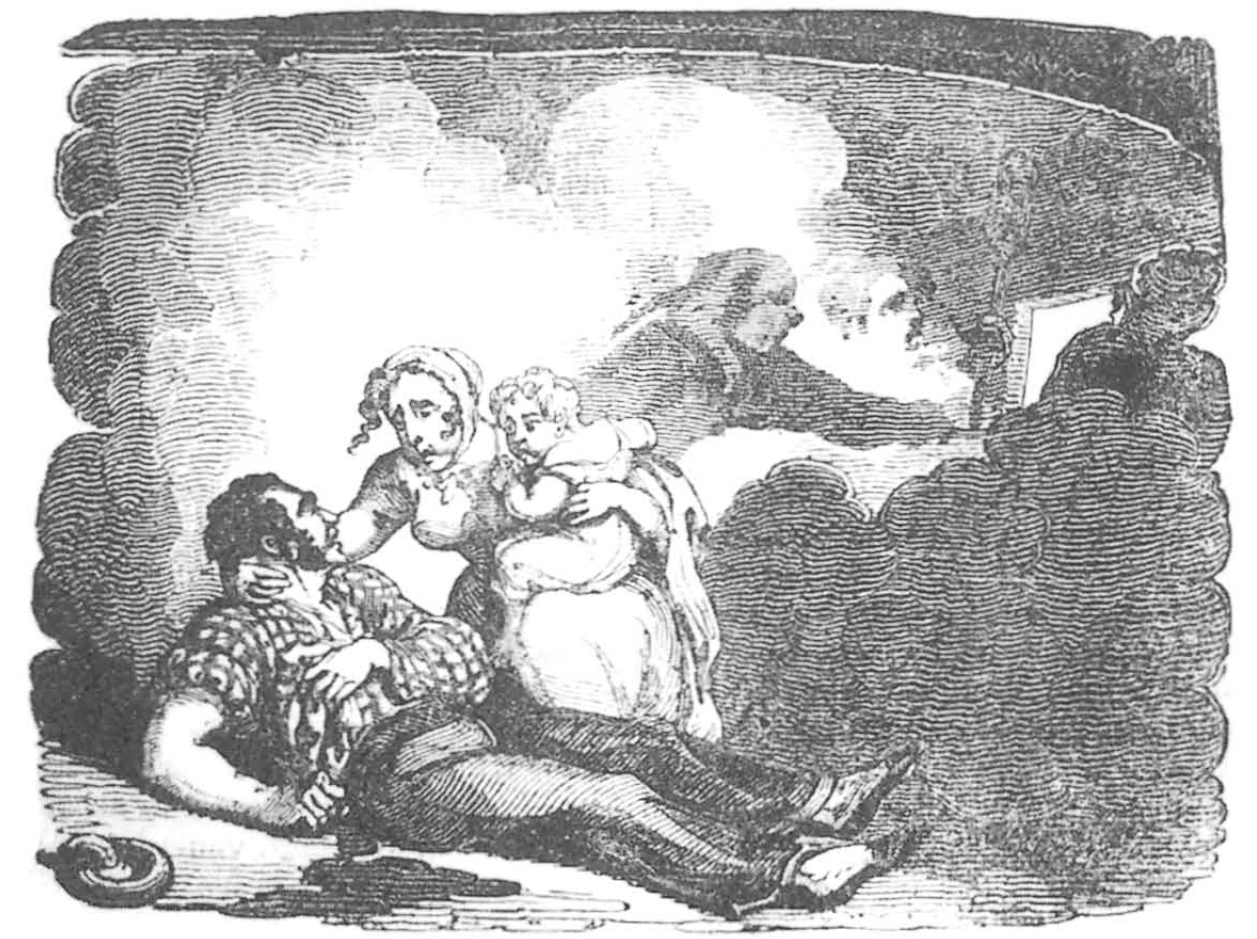

Childbirth

Childbirth was not an unusual occurrence at sea. It was always difficult. Children were often born in the midst of a battle or in bad weather, but even in quiet times there was no comfortable place for the birth to occur. The storerooms on the orlop deck provided the most privacy, but these rooms were not readily available; the warrant officer in charge had to be persuaded to give over the key. Births often took place on one of the tables between two guns on the lower deck, with only some canvas draped across to provide a modicum of privacy. From this situation comes the phrase “son of a gun,” a euphemism for “son of a bitch,” the assumption being that a child born between two guns on the lower deck was illegitimate, although in fact this was not usually the case.

There is an interesting anecdote concerning a child born in the United States ship Chesapeake during the Barbary Wars. (Seamen’s wives went to sea in the American navy as they did in all the major navies of the period.) The wife of seaman James Low, captain of the forecastle, bore a son in the boatswain’s storeroom on 22 February 1803, the day after the vessel sailed from Algiers. The baby was named for a midshipman, Melancthon Woolsey, who was godfather when the child was baptized by the ship’s chaplain on 31 March, and following the baptism Woolsey provided “a handsome collation of wine and fruit.” Mrs. Low was sick and could not attend the christening, so Mrs. Hays, the gunner’s wife, officiated. Either Woolsey did not extend his friendship to the other women on board or there was dissension among them, for the wives of the boatswain, the carpenter, and the corporal were not invited and “got drunk in their own quarters, out of pure spite.”25

Sexual Harassment

From the sparse records available, it appears that there was very little sexual harassment of the women. The warrant officers’ wives were safer from unwanted sexual overtures than seamen’s wives; a man would think twice before accosting his superior’s spouse. But the seamen’s wives also were fairly safe. The surprising evidence is that seamen, although they endured months or even years of celibate existence on board, usually left their shipmates’ wives alone. This was partly because a woman’s husband and his friends would make life miserable for a man who accosted the woman. It was also partly because the men were closely supervised around the clock. During the day they were under the eyes of the officers directing them in their work. At night there was usually an hourly check of the lower deck, primarily to establish that there was no unguarded light that could start a fire, but also to make sure that no disorder was occurring. All the same, there were times when a man off duty could find a woman alone in an unfrequented part of the ship; we know that homosexual activity went on despite the lack of privacy. Undoubtedly there were cases of women being sexually harassed that went unreported, but if incidents had been common, there surely would have been some mention of them in letters and journals.

I have found one instance of a woman attempting adultery but failing in the attempt: the case of the cuckolded coxswain. In the sloop Petrel, cruising off the coast of Greece in 1796, the coxswain’s wife, while her husband was away with some officers exploring the shoreline, was seen in cozy concourse with a seaman. The boat party, however, returned sooner than she expected, and the illicit affair was interrupted.26

The only example I know of a wife being raped occurred during a mutiny when both discipline and social restraints had been overthrown. This singular case took place in the thirty-two-gun frigate Hermione in the early-morning hours of 21 September 1797, after Captain Hugh Pigot and most of his officers had been murdered by the mutineers.27 Richard Redman, a twenty-four-year-old quartermaster’s mate, after joining in the slaughter of the captain and other officers, carried out a premeditated attack on the boatswain’s wife, the only woman on board.28 First he raided the officers’ wine supply and consumed a great quantity of Madeira. He then went down to the cabin of the boatswain, William Martin, where Martin and his wife were cowering. Redman was heard to shout, “By the Holy Ghost, the Boatswain shall go with the rest.” He then crashed into the cabin, grabbed Martin, and forced him up to the main deck, where he pushed him through a gunport to drown. He then returned to Mrs. Martin in the cabin, carrying more bottles of Madeira, “and was not seen again that night.”29

It is interesting that as violent as the Hermione mutineers were—they killed ten officers, including one in the last stages of yellow fever, whom they dragged from his bed and threw overboard—none of the men besides Redman tried to assault Mrs. Martin either during the mutiny or in the following days when they were taking the vessel to the enemy’s port of La Guaira on the Spanish Main.

At La Guaira the ship was given over to the Spanish, and the crew dispersed. Redman joined a Spanish merchant ship that was later captured by the British, whereupon he was identified as one of the Hermione mutineers and sent to Portsmouth to be court-martialed. In March 1799, on board the Gladiator at Portsmouth, although he claimed he was innocent of any wrongdoing, Redman was found guilty and sentenced to death; he was executed an hour after the close of the court-martial.30 In the evidence given at the court-martial, the only time Mrs. Martin was mentioned was when the captain’s steward testified that Redman had spent the night with her. All that is known about her following the Hermione’s arrival at La Guaira is that she took passage in a ship bound for the United States, hoping no doubt to get back to England from there. (She could not travel directly to England from an enemy port.)

WOMEN AT SEA FACING CRISES AND DEATH

Captain William Henry Dillon praised the women in his ship the Horatio for their help in saving the vessel when, in May 1815, she struck a rock off the island of Guernsey and tore a hole in her bottom. The vessel floated off, but water was pouring in through the opening. While the crew worked the pumps, a group of their wives quickly set to work “thrumming a sail” (sewing on strips of oakum to thicken it), which was then passed down the ship’s side and over the hole. This stanched the leak sufficiently to allow the vessel to get to Portsmouth for repairs. Unfortunately, in the process of getting the sail overboard, a boatswain’s mate, whose wife was present, fell into the water. A boat was lowered to help him, but the crew of the ship were terrified that if they delayed, they would all be lost. They pleaded with Captain Dillon: “Only one man, sir; we are upward of three hundred. Pray save us. We have no time to lose.” After several minutes the search was abandoned. The man’s wife, Dillon remarked, “was in sad distress at her loss.”31

In a rare instance when the wife of a newly impressed man went to sea, her sea experience was harrowing from beginning to end. The woman—her name is not recorded—was in the last month of pregnancy when she went on board the twenty-eight-gun Proserpine, Captain James Wallis, at Yarmouth to bid her husband goodbye. The ship was suddenly ordered to sea and sailed before the woman could return to shore. On 28 January 1799 the Proserpine headed into the North Sea bound for Cuxhaven near the mouth of the Elbe River to drop off the Honorable Thomas Grenville, a government official on his way to deliver important documents to Berlin. That same day the woman gave birth to a dead child.32

By late afternoon of the thirty-first the ship was within four miles of Cuxhaven when a gale came up, and there was such heavy snow that it was impossible to see to navigate further up the river. They were obliged to drop anchor. The following morning, ice had blocked the way into Cuxhaven. Captain Wallis stood out to sea, hoping to put Mr. Grenville ashore on the coast of Jutland. Heavy winds continued, and the Proserpine had only reached the mouth of the river when she was blown onto a sandbank. The crew attempted to get her off, but it was impossible for them to continue working in the bitter weather. By the following dawn, ice was up to the cabin windows, and everyone was suffering from the intense cold. (Vessels of that time were not heated.)

Captain Wallis realized that the only hope of saving his people was to abandon the ship and get everyone to the nearest village on the island of Newark, six miles away. They set out across the ice, blinded by snow and struggling to keep on their feet in the high wind, sometimes clambering over boulders of ice, at other times struggling through water up to their waists.

The only other woman on board was another seaman’s wife, “a strong healthy woman accustomed to the hardships of a maritime life,” carrying her nine-month-old child. She was not as sturdy as she appeared; both she and her baby died on the way to the village. Twelve seamen also died of exposure. The impressed man’s wife survived.33

Many wives went to the West Indies even though they knew in advance that they were likely to die of yellow fever. In July 1800 the old fifty-four-gun two-decker Tromp carried thirteen women and a female toddler to Martinique. The Tromp’s gunner, William Richardson, who described the voyage in his journal, had tried to persuade his wife to stay at home, but she “had fixed her mind to go,” and at length he gave his consent, “especially as the captain’s, the master’s, the purser’s, and boatswain’s wives were going with them; and the serjeant of marines and six other men’s wives had leave [from their husbands] to go.” The captain’s wife brought her maid, and the boatswain and his wife brought their two infants. “A person,” Richardson commented, “would have thought they were all insane wishing to go to such a sickly country!”34

The Tromp arrived in the harbor of Port Royal in Martinique after a six-week passage during which the captain’s wife gave birth to a son. It was not long after their arrival that the fever struck with a vengeance. “Every day,” Richardson reported, “we were sending people to the hospital, and few returned.” Among the first to die were the master and his wife, “large in a family way.” “Next died Mr. Campbell, the boatswain, leaving a wife and son and daughter on board.”35 Only three of the thirteen women survived: Mrs. Richardson, the boatswain’s widow, and the captain’s wife. (The wife of the captain was able to return to England not long after her arrival, but the other two women had no way to escape.)

Richardson’s wife almost succumbed to the fever; she would have died if she had not been carefully nursed. Rather than send her to the crowded, insanitary hospital, Richardson hired an airy room in the private house of a skilled nurse, a black woman, who provided constant care and efficacious herbal teas. He also found a French doctor who had spent most of his eighty years in the West Indies and so was familiar with yellow fever; the English doctors knew next to nothing about the disease.

Upon Mrs. Richardson’s recovery she and her husband continued to live in the Tromp under the most difficult circumstances. The ship had been converted into a prison ship and was now crammed with former French slaves. For two years the Richardsons, together with the few remaining officers and crew, were crowded into one small area at the stern of the main deck, the only space not filled with prisoners. The prisoners were desperate men, and there was the constant danger that they would take over the ship and murder the English on board. Prisoners escaped almost every night; the ship’s sides were so rotten that it was easy for them to loosen the bolts that held the ports shut. Mrs. Richardson, on the other hand, seldom got on shore since her husband only rarely got leave, even though he was a warrant officer, and it was dangerous for her to go alone.

At last, two years after her arrival in Port Royal, the Tromp was readied for sea, and she returned to Portsmouth on 5 September 1802. Mrs. Richardson’s friends in Portsmouth, who had heard that both she and her husband had died in the West Indies, “received her as one risen from the dead.” She did not go to sea again.36

Widows and Widows’ Men

William Richardson reported in his journal that when the Tromp’s boatswain died, he left a wife and two children on board, but he does not say what happened to them. Other sea journals are equally silent about the fate of a woman who became widowed on board. If her ship was not returning soon to England, she was apparently sent home in another naval vessel. No contemporary source explains how she managed on the voyage home without a man to sponsor her. Who hung her hammock each night and stowed it away each morning? She would not have been allowed to join the men in this duty. How did she feed herself and her children? No one tells us.

The widow of a man who had died of disease was worse off than one whose husband had been killed in action or in a shipboard accident. When a man died accidentally or in battle, his clothing and other effects were auctioned off and the proceeds given to his widow, but this could not be done if a man died of a contagious disease, or at least we hope not.

A seaman’s widow was entitled to her husband’s back pay when his ship was eventually paid off, but she seldom managed to get through the red tape necessary to get it. Many widows also failed to get the small pension due them because the process of obtaining it was so complicated. The widows of men killed in major battles sometimes received money from private benefactors or from funds raised by public subscription, but there was no such remuneration for widows of men who died of disease.

Widows were aided by a most curious system, one of the more bizarre traditions of the sailing navy. From 1733 onward, in every commissioned vessel’s muster book there were listed two “widows’ men” for every hundred men in the crew. They were rated as able seamen. The pay of these nonexistent men was collected in a pension fund for widows. The system, known as “dead shares,” was introduced during the reign of Henry VIII for the widows of commissioned and warrant officers. In 1695 it was diverted to the widows of seamen killed in action, and from 1733 onward it was paid for any man who died on board. It was not until 1829 that a less irregular pension system finally replaced it. In earlier centuries fictitious names were given to these ghostly ratings, but starting in the mid-eighteenth century the simple designation “widow’s man” was used.37

Widows’ men were the direct opposite of wives at sea: the wives were alive and present on board but were not mustered and so received no pay; the widows’ men did not exist but were listed in the muster book and paid.

Women Mustered in Hospital Ships

There was one situation in the Royal Navy in which women were actually mustered, victualed, and paid. This exception to the rule of male-only naval crews was instituted in the seventeenth century, when it was ordered that women were to be hired to serve in hospital ships as nurses and laundresses. In 1696 each of the six existing hospital ships was to be assigned six nurses and four laundresses. To allay fears that the women would seduce the medical staff or the patients, it was suggested that none of them should be under the age of fifty, and they were to be seamen’s wives or widows.38 They were paid able seamen’s wages. The job of nurse had little in common with the nursing profession of today. At that time nurses needed no medical skills; they merely fed and cleaned up the patients and changed the bed linen—when there was bed linen, that is.

There were continual complaints from the officers of the hospital ships that the women were drunk and disorderly, but then there were also complaints of the male assistants’ drunkenness. It is not surprising that both male and female workers escaped the misery of their surroundings in drink. Hospital ships were not pleasant places to live and work; they were usually worn-out sixth-rates or old and grimy converted merchant vessels. If they went to sea, they wallowed along behind the faster ships assigned to fight the enemy. There was usually only one surgeon aboard, about four surgeon’s mates, six nurses, four laundresses, a cook, and enough crew to work the vessel. The ships were jammed full of desperately sick men, often men with contagious diseases. The female nurses and laundresses had a difficult time, since they were especially vulnerable to sexual harassment and verbal abuse, having no husbands or other male protectors on board to defend them.

A 1743 plan of the gun deck of the hospital ship Blenheim indicates what life was like for the nurses.39 While the lieutenant, the surgeon, and the surgeon’s mates lived on the upper deck away from the patients, the nurses were housed in small cabins within the wards, separated from the sick men only by canvas bulkheads. The wards in the Blenheim were designated as follows: two for ague (malaria), two itchy wards (for diseases affecting the skin), two fever wards (for a wide range of contagious diseases that might include typhus, typhoid, yellow fever, and cholera), a ward for recovering fever patients, and one for flux (dysentery) patients. In the bow were two large storerooms “for dead men’s cloaths.” Why these clothes were saved is not clear. Surely this contaminated clothing was not auctioned off to seamen as was the clothing of those slain in fighting ships.

The Admiralty’s policy of hiring women for hospital ships was a matter of debate, and feelings ran high on both sides. Some felt that the female nurses provided the patients with a form of nurturing that only women could give. Others were convinced that female nurses were less responsible than their male counterparts.

A complaint was brought before the Admiralty on 10 January 1703 charging that the female nurses of the hospital ship Princess Anne, lying at Woolwich, “have done little or no service the last year but are continually drunk as often as opportunity would permit—and then very mutinous.”40 In response, the Admiralty sent Rear Admiral George Byng and Daniel Furzer, surveyor of the navy, to investigate conditions in the Princess Anne. In their report of 24 January 1703 they said that the captain and the surgeon of that ship told them that the female nurses on board “take up a great deal of room and are rather an inconvenience than otherwise.”41 Byng and Furzer recommended that the women be replaced by men.

The Admiralty, as usual, kept its options open. On 26 January it ruled that women would not be hired to serve in hospital ships, but it added the provision “except when circumstances required.” Such circumstances quickly developed. On 9 March 1703 three laundresses were hired when the Princess Anne was ordered to the Mediterranean.42 (Five additional nurses were also hired, and they too may have been female.) Again in 1705, five women were hired at Portsmouth to serve on a hospital ship ordered to the Mediterranean where “such persons are not commonly to be had.”43

The Regulations and Instructions of 1731 called for four washerwomen in each hospital ship. At Portsmouth in 1747 the hospital ship Apollo, on her way to India in the squadron of Admiral Edward Boscawen, mustered seven women as supernumeraries to assist the surgeon. They served for several years on the India station, and all but one of them was on board in 1749 when the Apollo was wrecked on the coast of Coromandel. The six women, together with most of the crew, perished. The one nurse who escaped the disaster was Hannah Giles, who had been sent back to England in the Harwich for undisclosed reasons shortly before the wreck of the Apollo.44

Female nurses were assigned to hospital ships throughout the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), although their presence was often resented. In 1759, for example, Dr. Garlick, surgeon of the hospital ship Princess Caroline, complained to the Sick and Hurt Board that the ship’s commander, Lieutenant Powell, regularly consumed a bottle of gin and then proceeded to “damn the nurses as bitches and threaten to tow them on shore.”45

Few if any female nurses served in hospital ships after the close of the Seven Years’ War. Laundresses continued to be hired in the latter part of the eighteenth century, but by the nineteenth century they too were gone.

Female nurses began serving on shore in 1754, when the earliest section of Haslar Hospital, the first naval hospital, opened. Like their seagoing counterparts, these women were repeatedly condemned for drunkenness and insubordination, and in 1854 they were replaced. They were, however, reinstated in 1885.46

WOMEN IN BATTLE

Women played two traditional roles in battle: they assisted the surgeon and his mates in patching up the wounded, and they carried powder to the guns from the magazine, a job shared with the young boys in the crew known as powder-monkeys.

John Nicol, a seaman in the seventy-four-gun Goliath, Captain Thomas Foley, reported on the women of that ship at the Battle of the Nile, 1 August 1798. In this great English victory Admiral Horatio Nelson’s fleet roundly defeated Napoleon’s ships, opening the attack at dusk as the French fleet lay at anchor in Aboukir Bay. The Goliath opened the action, passing through the line of French ships and anchoring on the land side of them. This battle was especially hellish because it was fought at close quarters at night, lighted only by the flash of the guns and the flames from the burning French ships. Nicol wrote:

My station was in the powder magazine with the gunner. As we entered the bay, we stripped to our trowsers, opened our ports, cleared, and every ship we passed, gave them a broadside and three cheers. Any information we got was from the boys and women who carried the powder. The women behaved as well as the men and got a present for their bravery from the Grand Signior.47

Nicol was misinformed on this point. It is true that following the battle a purse of two thousand sequins (coins equal to about nine hundred English pounds) was delivered to Lord Nelson from the Turkish sultan (always called the Grand Signior) to be distributed among the wounded seamen, but it is most unlikely that any women were among the recipients.48

Carrying gunpowder was strenuous and nerve-racking work. A woman had to clamber down the ladder from the decks to the powder room deep in the bowels of the ship, slide past the wet curtain that protected the stored powder from sparks, and grab a leather cartridge of powder. She then raced back up the ladders clutching the heavy cartridge, ran along the sand-strewn but still blood-slippery deck through the choking smoke and deafening gunfire to her assigned gun, deposited the cartridge, and once again ran down to the hold for another load. This work continued throughout the battle, since it was dangerous to keep a large supply of powder near the guns.

Nicol continued his report of the women:

I was much indebted to the gunner’s wife who gave her husband and me a drink of wine every now and then, which lessened our fatigue much.

There were some of the women wounded, and one woman belonging to Leith died of her wounds and was buried on a small island in the bay. One woman bore a son in the heat of the action; she belonged to Edinburgh.49

Childbirth during Battle

It was not unusual for a woman to give birth during battle; the noise and vibrations of the guns—not to mention the stress—brought on labor. It is impossible to imagine a worse situation in which to bear a child. The ship was cleared for action, all the furniture and partitions were stored away, and there was no one to aid the mother. There was, obviously, no help available from the surgeon or his mates; the surgeon’s quarters were crowded with the wounded waiting their turn to be treated. The services of the women assigned to the surgeon were sorely needed, but perhaps one of them was allowed to assist the woman in childbirth in another part of the orlop deck. Remarkably, in all the instances I have found of births during battle, both mother and newborn survived.

Women Mustered after the Battle

The names of four of the women in the Goliath at the Battle of the Nile were actually listed in the muster book two days after the battle; they served as nurses for a period of four months. The muster book notes that they were “victualed at two-third allowance in consideration of their assistance in dressing and attending on the wounded, being widows of men slain in the fight with the enemy on the first day of August.”50

The widows had no time to mourn the loss of their husbands; they were immediately ordered to continue to nurse the wounded at the close of the battle. In the intense heat of an Egyptian summer, this was a grueling task. (Most of the fleet had left Egypt with Nelson at the close of the fighting, but the Goliath and several other ships, their wounded still on board, were left behind to blockade the Egyptian coast.) Sarah Bates’s and Mary French’s husbands died during the battle, and their bodies were thrown through a gunport into the sea. Ann Taylor’s husband lingered for a week, and the husband of Elizabeth Moore did not die until 31 August, a month after the battle.

There is no record of when the four widows were able to return to England, for in the Goliath’s muster book the place, date, and reason for discharge of each woman have been carefully erased. There was something about their discharge that the Goliath’s officers wished to hide, but unfortunately there is no way to know what irregularity they were covering up.

Christina White was also present at the Battle of the Nile, and she too nursed the wounded for several months following the battle, but the captain of her ship, the Majestic, was not so generous as Captain Foley, and she was not mustered. Upon her return to England, White wrote a letter to Admiral Nelson explaining that she was left a widow with two children, and she asked for his help. “Your petitioner,” she wrote, “hopes that your Lordship will consider her worthy of your notice, since she attended the surgeon and nursed the wounded on the voyage home for a period of eleven weeks.”51 There is no record of any answer to her letter.

The Horrors of the Surgeon’s Quarters

Twenty-nine years after the Battle of the Nile, the role of women in battle had not changed. The seaman Charles M’Pherson wrote about the women in the Genoa at the Battle of Navarino, fought on 20 October 1827:

Nine of our petty officers had wives aboard who were occupied with the doctor and his mates in the cockpit, assisting in dressing the wounds of the men as they were brought down, or in serving such as were thirsty with a drink of clean water. Some of them pretended, or were really so much affected by the shocking sight around them, that they were totally unable to render any assistance to the sufferers. Two of the number, I think it but justice to mention, acted with the greatest calmness and self possession.52

The surgeon’s quarters were enough to turn anyone’s stomach, as M’Pherson’s description shows:

Illuminated by the dim light of a few pursers’ dips, the surgeon and assistants were busily employed in amputating, binding up, and attending to the different cases as they were brought to them. The stifled groans, the figures of the surgeon and his mates, their bare arms and faces smeared with blood, the dead and dying all round, some in the last agonies of death, and others screaming under the amputating knife, formed a horrid scene of misery, and made a hideous contrast to the “pomp, pride and circumstance of war.”53

While criticizing the squeamishness of the women, M’Pherson admitted that he himself almost fainted when he visited the cockpit after the battle: “The heavy smell of the place, and the stifled groans of my suffering shipmates brought a cold sweat over me; and I found myself turn so sick that I was obliged to sit down for a little on one of the steps of the ladder.”54

Women in the French Navy

Women also served in battle in the enemy’s ships. At the Battle of Trafalgar, fought on 21 October 1805, two Frenchwomen were pulled from the water by British boat crews after their ship, the seventy-four-gun Achille, exploded. The Achille had lost all her senior officers before she caught fire and blew up at sunset, by which time the fighting had almost ceased. The British rescued over two hundred of her company, but many drowned before the boats could pick them up. Over four hundred of the crew were lost in the battle.

One of the women, identified only by her first name, Jeannette, was originally from French Flanders. She had been stationed in the passage of the fore-magazine in the hold of the Achille, assisting in handing up the powder to the gun decks. When she realized that the ship was on fire, she scrambled up to the lower deck, climbed through a gunport, and leaped into the sea just before the ship exploded. She was burned on her neck and shoulders by molten lead falling around her, but she was able to cling to a plank for several hours until she was rescued by a British boat and taken to the Revenge, where she was given a cot in the officers’ quarters. Three days after the battle, having no idea if her husband was still alive, she went to the section of the ship where the French seamen were held to seek word of him. There he was, safe and sound. The couple was sent ashore at Gibraltar, a long way from Jeannette’s home in Flanders.55

The other woman from the Achille was taken on board the Britannia. She was naked when pulled from the water, having shed her clothing to keep from being pulled down by the wet garments. Second Lieutenant Halloran of the Britannia’s marines recorded in his journal, “Our senior subaltern of marines, Lieutenant Jackson, gave her a large cotton dressing-gown for clothing.” She too was sent to Gibraltar.56

More British Women in Battle

A newspaper at Mahon, on the island of Minorca, reported the sad story of the able seaman Joseph Phelan and his wife and baby on board the sloop Swallow in an engagement fought on 16 June 1812. Phelan, an Irishman, was twenty-four when he first entered the Swallow at Plymouth in April 1809.57 Perhaps Mrs. Phelan came on board at that time. On the day of the battle she assisted the surgeon despite having given birth three weeks earlier to a son, Tommy. Tommy was probably placed somewhere in the cockpit among the wounded, not an ideal nursery, but in sight of his mother. As Mrs. Phelan was attending one of her husband’s (and her own) wounded messmates, she heard that her husband had been hit. She rushed up to where he was lying on the main deck, and as she took him in her arms, a shot took her head off. He died immediately afterwards.

Following the battle, Phelan’s messmates addressed the problem of the orphaned Tommy; he desperately needed nourishment. At first they had little hope that he could be saved, but then one of them thought of the Maltese goat that provided the officers with milk. The officers agreed to lend the goat to suckle the baby, and at the time the news report was written—10 July 1812, three weeks after the death of his parents—Tommy was still on board, being cared for by the seamen and nursed by the goat, and was thriving.58

One seaman’s wife received a pension in her own right for having been wounded in the line of duty even though her name was not listed in the ship’s muster book. Eleanor Moor petitioned for a pension from Chatham Chest for “a fracture of the cranium.” She had received the wound on board H.M.S. Apollo in action with a French frigate on 15 June 1780 “while carrying powder to a gun at which her husband was quartered.” The governors of Chatham Chest wrote to the lords of the Admiralty on 11 August 1780 asking for special approval of Eleanor Moor’s request, “there being no precedent for the relief of persons not borne on the Ship’s Books.”59 The lords approved the application the next day, a singularly generous decision; perhaps she was personally known to one of them. She was awarded an annual pension of four pounds, a meager but standard amount.60

A LONG TRADITION ENDS

The number of women in naval vessels at sea gradually decreased after 1815 during the relatively peaceful years that followed the close of hostilities with France, although a few warrant officers’ wives continued to go to sea until midcentury. During the years 1839–43, for example, Mrs. Bull, the wife of the boatswain of the twenty-eight-gun Rattlesnake, sailed with her husband in the East Indies and China. He had served in the Napoleonic Wars and had probably been taking Mrs. Bull to sea for the past thirty years, and the captain, also a veteran of those wars, was accustomed to having warrant officers’ wives in his ship.61

In the steamships of the later half of the nineteenth century, only commissioned officers’ wives went to sea, and then only in carefully specified circumstances. By midcentury the navy was changing from its old ways whereby tradition had ruled and captains had run their ships as they saw fit.

In contrast to the earlier Regulations and Instructions, which simply stated that women should not be carried to sea without permission, the later Queen’s Regulations and Admiralty Instructions gave detailed guidelines concerning women at sea, and commanding officers were expected to conform to the rules exactly as written. It is worth quoting these later orders in order to show just how scant the earlier ones had been. The following Queen’s Regulations of 1879 are representative of those issued during the late nineteenth century:

No wife of any Officer or Man, nor any other woman, is to be allowed to reside on board or to take passage in a Ship except upon the express authority of the Admiralty, or when time and circumstance do not admit of a reference home, of the Commander in Chief abroad.

This authority may only be exercised by a Commander in Chief abroad when the ship is about to make a direct passage to one port from another and back; but on no account is it to be exercised when ships are cruising for practice or for evolutionary purposes; and every case is at, or before, embarkation to be specially reported to the Admiralty.

Whenever a Senior Officer may, on the formal requisition of an Ambassador, Minister, Chargé d’Affaires or Consul or of the Governor or Lieutenant-Governor of a Colony, receive, or order to be received, any woman for passage, he will at once report the circumstance to his Commander in Charge for the information of the Admiralty.

The Captain will in his Quarterly Return of Passengers [no such list was required under the earlier Regulations] be careful to include the name and particulars of every woman embarked or carried to sea during the quarter, except for the wives and daughters of Military persons embarked during the period [whose names would appear in army records].62

WOMEN DEPRIVED OF THE GENERAL SERVICE MEDAL

In 1847 it was decided that Queen Victoria would award a Naval General Service Medal to all the still living survivors of the major battles fought between 1793 and 1840—to all, that is, except the women.

Three women applied for the medal: Mary Ann Riley and Ann Hopping, who had participated in the Battle of the Nile in 1798, forty-nine years earlier, and Jane Townshend, who had served in the Defiance at Trafalgar in 1805. The four admirals who formed the committee to decide who would get the medal at first agreed to give it to women. Sir Thomas Byam Martin, the committee’s spokesman, wrote regarding Jane Townshend’s application, “The Queen in the Gazette of the first of June [1847] directs all who were present in this action shall have a medal, without any reservation as to sex, and as this woman produces from the captain of the Defiance strong and highly satisfactory certificates of her useful services during the action, she is fully entitled to a medal.”63

Then, however, Admiral Martin went on to explain that the committee had had second thoughts. Someone, very likely the queen herself, had disapproved of their initial decision. The idea of a woman participating in a naval battle was distasteful to Victoria. The queen was strongly convinced that a woman should know her place, which was at home and under the control of a man. (She later bitterly opposed the campaign for women’s rights. “God created men and women different,” she said. “Let them remain each in their own position.”)64 Admiral Martin explained the committee’s final decision to disallow women’s claims to the medal: “Upon further consideration this [giving of the medal to women] cannot be allowed. There were many women in the fleet equally useful, and it will leave the Army exposed to innumerable applications of the same nature.” The reasons given for denying the three women the medal were clearly nonsense. More than twenty thousand men received it, some simply because they had been on board during a battle. Daniel Tremendous McKenzie, for example, was presented with the medal for having been born in the Tremendous during the battle of the Glorious First of June, 1794. His rank is listed in the medal roll as “baby.” His mother, if she was still alive in 1847, could not receive the medal.65

The four admirals on the committee, although not from a class known for its support of the rights of women, were honorable men who recognized that the women were entitled to the medal. However, they capitulated to political pressure. In the end, they decided to conform to the traditional government stance of centuries: women who went to sea on the lower deck of naval vessels officially did not exist.66