![]()

The Story of Mary Lacy, Alias William Chandler

Oh when I was a fair maid about seventeen

I enlisted in the Navy for to serve the Queen.

I enlisted in the Navy, a sailor for to stand,

For to hear the cannons rattling, and the music so grand.

![]()

They sent me to bed, and they sent me to bunk,

To lie with the sailors, I never was afraid.

But putting off my blue coat, it often made me smile

To think I’d laid with a thousand men, and a maiden all the while.

—“When I Was a Fair Maid”

ON A SPRING DAY IN 1759 the servant girl Mary Lacy decided to run away from home. She explains in her autobiography, “A thought came into my head to dress myself in men’s apparel and set off by myself, but where to go I did not know, nor what I was to do when I was gone.” What she did was join the Royal Navy for what proved to be a twelve-year stint.

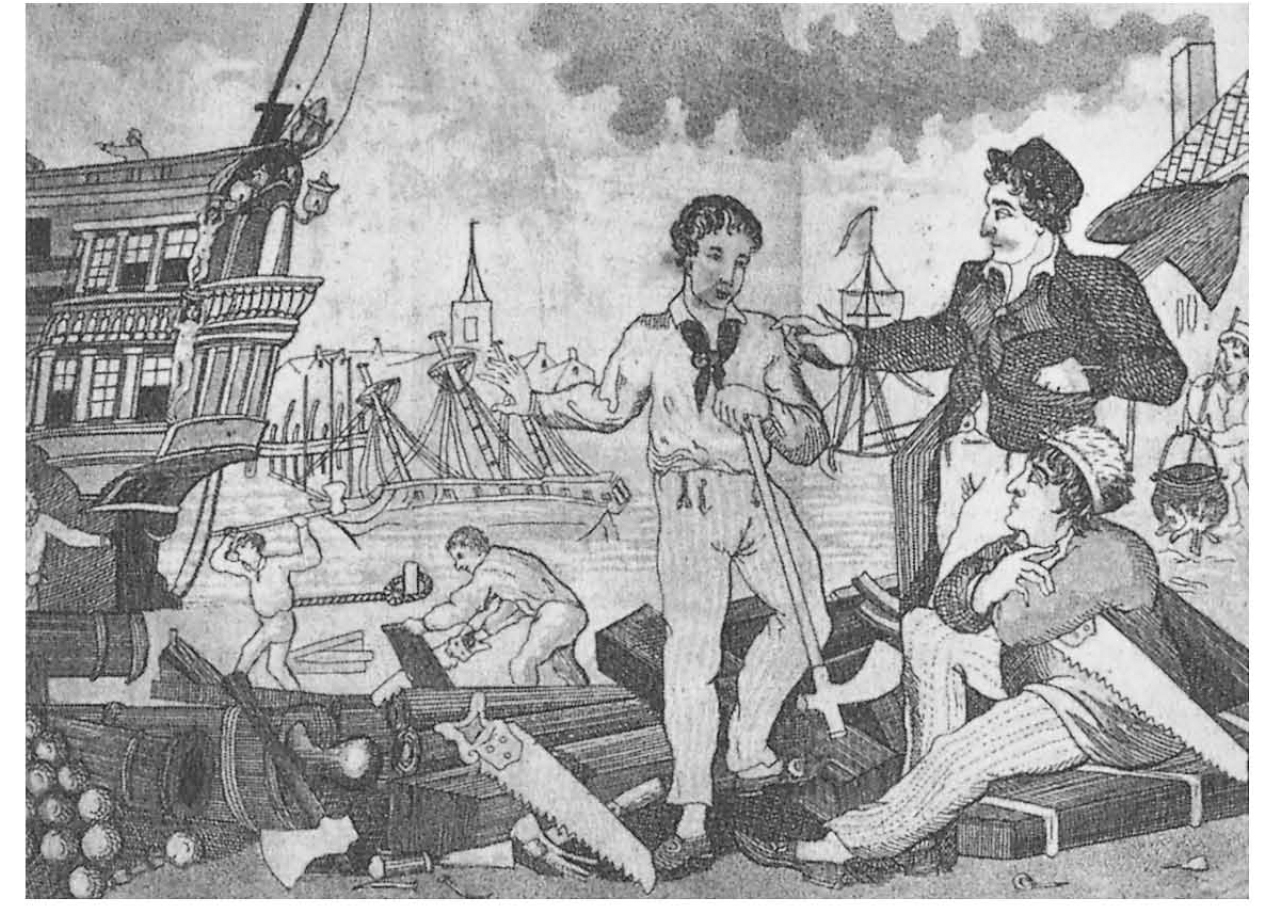

Lacy published her autobiography, The History of the Female Shipwright, in 1773 in conjunction with a London publisher and printer, M. Lewis.1 Three abbreviated editions were issued in the United States in the early nineteenth century.2 Then her story was forgotten.

Muster books confirm that she did indeed serve in the ships she tells about, and Admiralty minutes note that she served seven years as an apprentice at Portsmouth Dockyard and then worked there as a fully qualified shipwright. In contrast to Hannah Snell and Mary Anne Talbot, Mary Lacy never became a celebrity; there is no clue to what became of her after her book was published.

No portrait exists, and she never described her own appearance. We only know that she was of small stature and that she easily passed for a boy. When she was in her late twenties and working at Portsmouth Dockyard under the name William Chandler, her fellow workers described her as a “little man” whose girlfriend was too large for “him.” When it was rumored that Chandler was a girl, the men of the yard found it hard to believe: “There is not,” they said, “the least appearance of it in the make or shape of him.” Unlike most of her fellow seamen, Lacy was literate and could write down her story herself; she has a galloping, no-nonsense style that is easy to identify. Occasionally, however, a passage is interjected that has a different tone, stilted and sermonizing, and it is probable that these sections were inserted by the publisher Lewis or a hireling of his in a clumsy attempt to discount Lacy’s lesbian propensities. An example is found in the book’s preface:

It will not be amiss to conclude this address by explaining my motives for endeavoring to be as frequently as possible in the company of women in the way of courtship, which were: In the first place, to avoid the conversation of the men, which I need not observe, was amongst those of this class [seafaring men] especially, in many respects, very offensive to a delicate ear; and, secondly, for the sake of affording me a more agreeable repast amongst persons of my own sex, many of whom, I am sorry to say, were too much addicted to evil practices by their unlawful commerce with the other [sex], as will on many occasions appear in the course of the story.

It seems that Lewis, while well aware that Lacy’s anecdotes of her amorous adventures with women would increase book sales, felt it necessary to make a token bow to morality, especially since a lot of his profits came from publications of puritanical religious groups such as the well-funded Moravian Brethren.3 He wavered. In the text above, after his peculiar apologia for Lacy’s courting of women, he could not resist adding a titillating forecast of her adventures with prostitutes and other errant females.

Mary Lacy felt no such ambivalence. She took on the guise of a man with the greatest enthusiasm, never questioning her right or ability to do so. In fact, she was so comfortable in her male role that as one reads her text, it is easy to forget that she was a woman. Except for the note in the preface, she did not dissemble about her flirtations with women. Women of all ages were attracted to her, and she to them.

It may have been Lewis who placed special emphasis on Lacy’s teenage crush on a young man she met at a dance while she was still working as a domestic servant. In several passages it is explained that she ran away from home in order to find respite from her lovelorn state. From the text as a whole, however, it is evident that she left home because she resented the restrictions of her life as a nursemaid, and because she liked the idea of acquiring a male identity, which she could not do in her home town.

Lewis may also be responsible for the addition of what could be a bit of fiction added at the very end of the autobiography: a claim that after Lacy resigned from the navy she married a “Mr. Slade” (no first name is given). More about that later.

Because Mary Lacy’s autobiography is the only reliable firsthand account of naval life written by an eighteenth-century woman seaman, it seems worthwhile to give extensive excerpts from her book, but to reproduce here all 191 pages of her story would be excessive. I have tried to select the most representative anecdotes from each period of her career, and to skip material that is not pertinent to our subject. Lacy herself so clearly reveals her goals, her attitudes, and her opinions that her text needs little editorial comment.

The book begins:

After mentioning my maiden name, which was Mary Lacy, it will be proper to inform the reader that I was born at Wickham, in the county of Kent, on the twelfth of January, 1740; but had not been long in the world before my father and mother agreed to live at Ash, so that I knew little more of Wickham than I had learned from my parents, on which account Ash might almost be reckoned my native place.

My father and mother were poor, and forced to work very hard for their bread. They had one son and two daughters, of whom I was the eldest. At the proper time, my mother put me to school, to give me what learning she could, which kept me out of their way whilst they were at work; for being young, I was always in mischief; and my mother not having spare time sufficient to look after me, I had so much of my own will that when I came to have some knowledge, it was a difficult matter for them to keep me within proper bounds.

After I had learned my letters, I was admitted into a charity school, which was kept by one Mrs. R——n; and she, knowing my parents, took great pains to instruct me in reading. As I took my learning very fast, my mistress was the more careful of me; for she was indeed as a mother to me; and in these respects was more serviceable than my parents could possibly be.

When I was old enough to learn to work, my mistress taught me to knit; which she perceiving me very fond of learning, employed me in knitting gloves, stockings, nightcaps, and such sort of work so that I soon perfected myself in it; which I was the more encouraged to as my mistress rewarded me for every piece of knitting, and all the money I earned she reserved in a little box; so that when I wanted anything, she would buy it for me. Thus, by the help of God and good friends, I was no great charge to my parents; for being always at school, my mistress set me about all manner of work in the house; so that, though young, I was very handy, and in a way of improvement.4

About this time I used to go on errands for my neighbors, and help them [with] what I could; but that practice, by occasioning me to go pretty much abroad in the streets, became very prejudicial to me for I was thereby addicted to all manner of mischief, as will appear by the following instance: There was one C——h——e Cipp——r about my age that lived in Ash with whom, when I could get out, I always kept company, and when together [we] did many unjustifiable actions. One day we took it into our heads to purloin a bridle and saddle out of the stable of Mr. John R——n, butcher at Ash, who kept a little horse in a field about half a mile from the town. This horse we caught, put the saddle and bridle on, and rode about the field till we were tired, and afterwards restored them to the place from whence we took them.

I liked riding so well that I never was easy but when among the horses; for I used to go to Mr. R——h——d——n and say, “Master, shall I fetch your sheep up out of the field?” And if he wanted them, I immediately took the little horse, without saddle or bridle, and mounting on his back, set off as fast as the horse could go, thus running all hazards of my life; and was so wild and heedless that if anybody took notice of my riding so fast, and told me I should fall off and break my neck, my answer was, “Neck or nothing!”

During Lacy’s childhood her mother was the most important person in her life. She scarcely mentions her father or her siblings:

I then thought my mother was my greatest enemy; for being a very passionate woman, [she] used to beat me in such a manner that the neighbors thought she would kill me. But after my crying was over, I was out of the doors again at my old tricks with my playfellows and frequently stayed out all day long and never went home at all, for which I was afterwards to be corrected.

At about the age of twelve Lacy entered domestic service, and for the next seven years she lived and worked in a series of households in Ash. Although her employers treated her well, she fretted under the restrictions imposed on her liberty by her long hours of household duties: “I was so very thoughtless and discontented,” she explained, “that I was always ill or had some complaint or other to make.… Being of a roving disposition, I never liked to be within doors.”

In her later teenage years Lacy often sneaked out of her employers’ residence to “be dancing all the night long” at a house where a musician played the violin “for the young men and maids of the town” to dance to, and she became enamored of one of her dancing partners:

I now embraced all opportunities of going out to dance with my sweetheart, for when I was with him I imagined myself happy. But this young man did not perceive that I loved him so much, and it happened very unfortunately I did not tell any of my friends of it, which if I had done, it would probably have been better for me, for my mother would no doubt have persuaded me [to forget the young man] for my good. But I afterwards felt the bad effects of concealing this warm affection. I could not blame the young man since he had never given me any reason for to do.

Hereupon I was very unsettled in my mind, and unable to fix myself in any place; nevertheless, I carried it off as well as I could.…

But my mind became continually disturbed and uneasy about this young man, who was the involuntary cause of all my trouble, which was aggravated by my happening to see him one day talk to a young woman: the thoughts of this made me so very unhappy that I was from that time more unsettled than ever.

Later in the text Lacy harks back to her infatuation with this young man with a warning against flirtations with the opposite sex:

I shall here take an opportunity of advising all maidens never to give their minds to frequent the company of young men, or to seem fond of them, and I would also caution them not to addict themselves to dancing with the male sex as I wantonly did. But had I been in bed and asleep, which I ought to have been, the unknown sorrows I have since felt and experienced would not have befallen me. But then I was young and foolish and had not the thought or care of an older person. I would likewise admonish all young men to beware how they marry; for I have seen so much of my own sex that it is enough for a man to hate them. However, there are good and bad of both sexes.

A short time after, a thought came into my head to dress myself in men’s apparel and set off by myself; but where to go I did not know, nor what I was to do when I was gone. I had no thought what was to become of me, or what sorrow and anxiety I should bring upon my aged father and mother because of me; but my inclinations were still bent on leaving home.

In order to do this I went one day into my master’s brother’s room, and there found an old frock [coat], an old pair of breeches, an old pair of pumps, and an old pair of stockings, all of which did very well. But still [I] was at a great loss for a hat. But then I recollected that my father had got one at home if I could but procure it unknown to my parents; I therefore intended to get it without their knowledge. Whereupon I went to my mother’s house to ask her for a gown which I had given her the day before to mend for me. She answered, I should have it tomorrow. But little did my poor mother know what I wanted; for I went immediately into my father’s room, took the hat, put it under my apron, and came downstairs. But I never said goodbye or anything else to my mother, but went home to my place [the house where she worked] and packed up the things that I had got, and now only waited an opportunity to decamp.

On the first day of May, 1759, about six o’clock in the morning, I set off, and when I had got out of town into the fields, I pulled off my clothes and put on the men’s, leaving my own in a hedge, some in one place and some in another.

Having thus dressed myself in men’s habit, I went on to a place called Wingham where a fair was held that day. Here I wandered about till evening; then went to a public house and asked them to let me have a lodging that night for which I agreed to give two pence. Now all the money I had when I came away was five pence.

Accordingly, I went to bed and slept very well till morning, when I got up and began to think which way I should go, as my money was so short; however, I proceeded toward Canterbury.

She hitched a ride on the back of a post chaise (a horse-drawn carriage), “not knowing whither I was going, never having been so far from home in my life,” and rode first to Canterbury, then onward to what turned out to be Chatham, where one of the great naval dockyards was located:

When the chaise had reached Chatham, I got down but was an utter stranger to the place, only I remembered to have heard my father and mother talking about a man’s being hung in chains at Chatham; and when I saw him, I thought this must be the place.

This was merely coincidence. Lacy was not aware that in all the larger towns of England, corpses of felons were hung in chains as a reminder to the populace of the fate of lawbreakers.

At Chatham she spent her last penny on bread and cheese and so had no money to pay for lodging:

I walked up and down the streets, as it was the fair time, and sauntered about till it was dark. As I stood considering what I should do, I looked about me and saw a farmhouse on the left hand of Chatham as you go down the hill. I thought within myself I would go to it and ask them to let me lie there, but when I came down to the house, I was ashamed to make the request.

In this distressed situation I continued some time, not knowing how to proceed; for money I had none, and to lie in the streets I never was used to, and what to do I did not know.

But at last I resolved to lie in the straw [in the barnyard close to the farmer’s pigs], concluding that to be somewhat better than lying in the street.… [Throughout the night] I was afraid to move, for when the pigs stirred a little, I thought someone was coming to frighten me. Therefore, I did not dare to open my eyes lest I should see something frightful. I had but very little sleep.

When it was morning, I got up and shook my clothes and looked about to see if anybody perceived me get out. I then came down to the town and went up to some men that belonged to a collier [a coal-carrying vessel] who gave me some victuals and drink with them.

While I was standing here, a gentleman came up to me and asked me if I would go to sea, “for,” said he, “it is fine weather now at sea, and if you will go, I will get you a good master on board the Sandwich.”

I replied, “Yes, sir.”

The Sandwich, a ninety-gun ship of the line, had recently been launched at Chatham and had not yet collected a crew, although a few of the warrant officers were already living on board.5 At this time the navy was desperate for men. England was in the third year of the Seven Years’ War against the French. Naval ships were fighting in North America, the West Indies, Africa, and India, and at home, only the navy stood between Great Britain and a French invasion.6 It was a happy surprise for a naval recruiter to come upon a healthy young volunteer.

He then showed me the nearest way on board, but instead of going to St. Princess’s bridge (as the gentleman had directed me), I went over where the tide came up, being half up my legs in mud. But at length I got up to the bridge and seeing the boat there I asked the men belonging to it if they were going on board the Sandwich. They told me they were and asked me if I wanted to go on board. I told them yes. They inquired who I wanted there. I told them the gunner. They laughed, said I was a brave boy and that I would do very well for him. But I did not know who was to be my master, or what I was to do, or whether I had strength to perform it. They then carried me on board.… When getting out of the lighter into the Sandwich, I thought it was impossible for such a great ship to go to sea.

Lacy was directed to the gunner:

When the gunner saw me he asked where I came from and how I came there. I told him I had left my friends. He inquired if I had been ’prentice to anybody and run away. I told him no.

“Well,” said he, “Should you like to go to sea?”

I replied, “Yes, sir.”

He then asked if I was hungry. I answered in the affirmative, having had but little all the day. Upon this he ordered his servant to serve me some biscuit and cheese. The boy went and brought me some and said, “Here, countryman, eat heartily,” which I accordingly did; for the biscuit being new, I liked it well, or else my being hungry made it go down very sweet and savory.

The gunner’s servant was Jeremiah Paine, a young man about Lacy’s age who soon became her good friend.7

After I had eat sufficiently, the gunner came and asked my name. I told him my name was WILLIAM CHANDLER, but God knows how that name came into my head, though it is true that my mother’s maiden name was Chandler, and my father’s name is William Lacy.…

I had been on board the Sandwich about four days when the carpenter came on board. He had only one servant who was at work in Chatham Yard, so that at that time he had none on board. The gunner told me the carpenter would be glad to have me as his servant. He [the gunner] was not willing I should be the captain’s servant, that being the worst place in the ship; but at that time I did not know which was the best or the worst.

The gunner, together with his fellow warrant officers, was envious of the number of servants allowed the ship’s captain and the special privileges they received. He was not about to pass a lively young lad over to a commissioned officer.

Mr. [William] Russel, the gunner, spoke to Mr. Richard Baker, the carpenter, for me.8

Baker accepted Mary, alias William, as his servant and began at once to teach her her duties:

He first of all ordered me to fetch him a can [a mug] of beer. I accordingly went and brought it to him.

“Now,” said he, “you must learn to make me a can of flip [a heated mixture of beer, spirits, and sugar], and to broil me a beefsteak, and to make my bed. Come, I will show you how to make my bed.”

So we went to his cabin, in which there was a bed that turned up [a hammock], and he began to take the bedclothes off one by one.

“Now,” said he, “you must shake them one by one, you must tumble and shake the bed about, then you must lay the sheets on, one at a time, and lastly, the blankets.”

I replied, “Yes, sir.”

“Well,” said he, “you will soon learn to make a bed, that I see already.”

But he little knew who he had got to make his bed. He not having any suspicion of my being a woman, I affected to appear as ignorant of the matter as if I had known nothing about it.

He then provided for me a bed and bedding and directed his mate to sling it up for me.

When I attempted to get into bed at night, I got in at one side and fell out at the other, which made all the seamen laugh at me. But, as it happened, there were not a great many on board, for being a new ship, but few had entered on board of her. My hammock was hung up in the sun deck, but [later] when the whole ship’s company was on board, it was taken down and placed below in the wing where the carpenter and the yeomen both were. Now it was better for me to lay there than anywhere else, but I was very uneasy lying there on account of a quartermaster that lay in that place whom I did not much like.

Lacy’s use of the word uneasy suggests that the man was sexually threatening; attacks on ship’s boys were not uncommon.

And when I came to lie in the blankets, I did not know what to do, for I thought I was eat up with vermin, having been on board ten days and had no clothes to shift myself with, so that I looked black enough to frighten anybody.

Baker was proud of his status as ship’s carpenter and wanted to make sure that his servant reflected well on him. Lacy noted later in the book:

He always caused me clean my own shoes as well as those that belonged to him, and if they were not done to his mind, he would kick me with great violence. Whereupon he peremptorily expressed himself thus: “You dog, I will make you go neat and clean, for you are a carpenter’s servant and you shall appear as such.”

Baker directed Mary to visit him at his house in Chatham to get a bath and some decent clothes. When she arrived there, he was sitting in the kitchen, and he asked her if she was hungry.

Indeed I thought I could gladly eat a bit of bread and butter and drink a basin of tea, for I even longed for some [tea], having had none since I came away from Ash. But I told him I was not hungry; notwithstanding which, he, being a merry man, said to me, “You can eat a little bit.”

I answered, “Yes, sir.”

On my saying this, my mistress gave me a basin of tea and a bit of bread and butter, more than I could eat, but I quickly found a way to dispose of the remainder, for what I could not eat I put in my pocket.

When I had eat my breakfast, my master called me out backwards, where there was some soap and water to wash myself with. How glad was I, hardly being able to contain myself for joy. But there was something that gave me greater pleasure, for after I had washed myself, my mistress gave me a clean shirt, a pair of stockings, a pair of shoes, a coat and waistcoat, a checked handkerchief, and a red nightcap for me to wear at sea. I was also to have my hair cut off when I went on board, but this operation I did not like at all, yet was afraid to say anything to my master about it.

Her mistress also bought her two checked shirts and a pair of shoes:

Therefore, I thought that I was a sailor, every inch of me.

Baker had a chest made for Mary to store her clothes in, warning her that she should keep it locked, for the seamen would steal the teeth out of her head if they could.

After this my master began to teach me the nature of the ship and how to cook for him, which gave me an opportunity of discovering his natural temper. Sometimes on mere trifling occasions he was very hot when things were not according to his mind. On that account I was always afraid of him, and when he was in a passion [I] stood with the cabin door in my hand in order to make an escape, which, when I did, he always beat me. This usage I could hardly brook when I knew that I was as real a woman as his mother. Besides, when at home, I could not bear to be spoke to, much less to have my faults told me. But now I found it was come to blows and thought it was very hard to be struck by a man; which occasioned me to reflect that there was a wide difference between being at home and in my present situation abroad.

On 20 May 1759 the Sandwich sailed to Black Stakes to take in her guns, and on 10 June she moved to the Nore, where the remainder of her crew were collected.9 She had a complement of 750 men.

We had now got a great number of men on board; some we had from the Polly Green, some from one ship, and some from another. These men were paid off from the several ships to come on board of us.10

While we lay at the Nore, there came a bumboat woman on board of us to sell all sorts of goods. This woman, being an acquaintance of my master, had the use of his cabin, and I was desired to boil the teakettle for her and to do anything she ordered me. I was glad of it, for she was very good to me and gave me a new purse to put my money in. Now my master kept the key of the roundhouse [where the women living in the crew’s quarters went to the toilet]…and he told me not to let them have the key unless they gave me something. By this means I got several pence from them.

On 21 June the Sandwich set out to join Admiral Edward Hawke’s large squadron blockading the harbor of Brest where the French fleet was gathered, and in July Rear Admiral Francis Geary and his large retinue transferred to the Sandwich.11

In the navy of this era it was the practice to include among the numerous servants of admirals and captains a special group of “young gentlemen” drawn from the upper classes who were not servants in the usual sense but were training to become commissioned officers. These snooty boys considered it a prerogative of their superior social station to bully the lower-class boys who served the boatswain, the gunner, and the carpenter. The young gentlemen serving Admiral Geary were no exception:

Among the admiral’s servants there were a great number of stout boys, very wicked and mischievous,… [who] were every now and then trying to pick a quarrel with me.…

One day being sent down to the galley to broil a beefsteak, one of these audacious boys, whose name was William Severy, came and gave me a slap in the face that made me reel.… Lieutenant Cook [the ship’s cook], knowing me better than any of them,…told me I should fight him and, if conqueror, should have a plum pudding, and that he would, in the meantime, mind the steak. Upon which I went aft to the main hatchway and pulled off my jacket, but they wanted me to pull off my shirt, which I would not suffer for fear of it being discovered that I was a woman, and it was with much difficulty that I could keep it on.

Hereupon we instantly engaged and fought a great while, but during the combat, he threw me such violent cross-buttocks… [as] were almost enough to dash my brains out, but I never gave out, for I knew that if I did I should have one or other of them continually upon me. Therefore, we kept to it with great obstinacy on both sides, and I soon began to get the advantage of my antagonist, which all the people who knew me perceiving, seemed greatly pleased, especially when he declined fighting any more, and the more so because he was looked upon as the best fighter among them. This contest ending favorably for me, I reigned master over the rest, they being all afraid of me; and it was a most lucky circumstance that I had spirit and vigor to conquer him who was my greatest adversary, for if I had not I should have been [so] harassed and ill treated amongst them that my very life would have been a burden.

As soon as I had put myself in some tolerable order, I went for the steak and carried it to [my master’s] cabin, being a little afraid that I should be chastised.

“Well,” said he, “you have been a long while about the steak, I hope it is well done now.”

“Yes, sir,” said I.

“Why,” says he, looking very attentively, “I suppose you have been fighting?”

I answered, “Yes, sir, I was forced to fight or else be drubbed.”

“But,” said he, “I hope you have not been beat.”

I replied, “No, sir.”

Upon the whole I came off with flying colors. From this time, the boy and I who fought became as well reconciled to one another as if we had been brothers, and he always let me share what he had.

One day Lacy saw some of the seamen dictating letters home and decided she would write to her parents, whom she had not contacted since running away two months before:

I could write but very indifferently, but to entrust any person with my thoughts on this occasion I imagined would be very improper.

She composed the following letter, dated 3 July 1759:

Honorable Father and Mother,

This comes with my duty to you, and hope that you are both in good health, as I am at present, thanks be to God for it. I would have you make yourselves as easy as you can, for I have got a very good master who is carpenter on board the Sandwich, and am now upon the French Coast, right over Brest. Shall be glad to hear from you as soon as you can. So no more at present from,

Your undutiful daughter,

Mary Lacy

P.S. Please to direct [letters] thus: For William Chandler on board the Sandwich at Brest.

Six weeks later she received an answer from her mother, who was so relieved to know that Mary was alive that she made no mention of the startling fact that her daughter not only had adopted a male identity but had joined the navy. Her letter begins:

My dear child,

I received yours safe and was glad to hear that you are in good health, but I have been at death’s door mostly with grief for you. Your clothes, after your departure, were found in a hedge, which occasioned me to think you were murdered. I have had no rest day or night, for I thought that if you had been alive, you would have written to me before.

In the meantime, Lacy was stricken with a severe attack of what she called rheumatism; it was probably a form of rheumatoid arthritis. (She was to suffer from this disease on and off for the rest of her naval career and ultimately was forced to resign because of it.) When she showed Baker her swollen fingers, he thought that she had gout, from which he himself suffered. It was then believed that gout was caused by too much rich food and port wine:

He fell a-laughing at me, adding, “Hang me if William is not growing rich. You dog, you have got the gout in your fingers.”

It was no joke to Lacy. Her legs swelled to the point where she could not walk. She was carried down to the sick bay, “a nasty, unwholesome place.” Her master sent her tea and buttered biscuits as a special treat every day, but this was little comfort, for she received her food from the hands of an old man “who was of so uncleanly a disposition that had I been ever so well, I could not have relished it from him.” She grew worse and worse “and was much altered.”

After several weeks she sent word to her master that she would die if she remained in the sick bay. He arranged to have her brought up to his cabin for several hours each day, and she began to recover, but she was very lame for a long time:

My master got me crutches with a spike at each end for my safety to walk about on the deck, and when anybody affronted me in an ill-natured way, I used to throw my crutch at them.

Baker used to tease her, saying that in a battle she would not be able to bring up the gunpowder fast enough.

I replied, “I’ll take it from the little boys, and cause them to fetch more before the gun shall want powder,” at which he laughed heartily to hear me talk so, as he well might.

To spend months at sea patrolling the Bay of Biscay was both tedious and perilous. The bay was notorious for its contrary winds and dangerous coasts, and English charts were not always accurate. The rallying point of the squadron was just off the island of Ushant at the entrance to the English Channel, an especially dangerous position. Sailing ships were cautioned not even to come within sight of the island’s treacherous rocks; a French proverb warned, “Who sees Ushant sees his own blood.”12 And perhaps because the Sandwich was a new ship, constructed in the rush of wartime with improperly seasoned wood, she was less seaworthy than other vessels, and her crew were especially afflicted with illness.

On 29 August 1759 the Sandwich had to go to Plymouth for repairs and to send her sick to the hospital. She returned to her station at the end of September.13 As the autumn stormy season progressed, one gale was quickly followed by another. Crews were not only exhausted from fighting to keep their ships from being wrecked; they were also suffering from lack of fresh food and beer, for it was proving difficult for the victualing ships sent out from England to get supplies on board the blockading vessels in the rough seas.

Lacy made no specific comments on these storm-ridden months. She only remarked in passing:

A person who is a stranger to these great and boisterous seas would think it impossible for a large ship to ride in them; but I slept many months on the ocean where I have been tossed up and down at an amazing rate.

On 7 October the Sandwich, battling a storm, sprang her maintopmast; other ships were also damaged. On the twelfth, in the continuing westerly gale, the fleet sailed for Plymouth for repairs and victualing, leaving only a few of the frigates to watch the French fleet. Hawke assured the Admiralty that “while this wind shall continue it is impossible for the enemy to stir.”14 This time he was right.

On 7 November another furious westerly gale drove the fleet from their station. They sought shelter at Torbay.15 On the way there, however, the Sandwich once again sprang her mainmast and shredded her sails so that she could not be maneuvered into the harbor. She spent the night of the eleventh fighting the storm off the dangerous Devon coast. Lieutenant Baker’s report in his log was wistful: “The fleet anchored in Torbay, but we was obliged to keep the sea.”16 When, on 14 November, most of Hawke’s ships cleared Torbay to return to Ushant, the Sandwich and two other storm-disabled vessels had to go to Plymouth for repairs, and the Sandwich, as before, needed to get her sick seamen to the hospital.

On the fifteenth Hawke learned that, contrary to his expectations, the French fleet had come out of Brest Harbor, and he guessed correctly that they were headed south for Quiberon Bay to pick up the soldiers who were gathered there awaiting the planned invasion of Great Britain. Hawke’s ships set out in hot pursuit.

The same day, Geary wrote to the secretary of the Admiralty from Plymouth:

Please acquaint their Lordships that I arrived here this morning in His Majesty’s Ship Sandwich, in company with the Ramillies and Anson, in pursuance of an order from Sir Edward Hawke…and so soon as I can possibly get the sick out of the ship and receive others in lieu, and have got a new maintopmast, maintopsail yard and sails in lieu of what was sprung and split in the last gale of wind, together with the stores and provisions completed, I shall proceed with the utmost dispatch to rejoin Sir Edward Hawke, whom I parted company with last night at 10 o’clock off the Start [Start Point south of Torbay] with a fine breeze of wind at N.N.E.17

The following day he informed the Admiralty that he would sail “this night or tomorrow morning.”18 No such luck! A new gale came on, and the ships could not get under way. On 17 November Geary learned that the French fleet was at sea, but it was not until the nineteenth that he at last got out of Plymouth Sound. The Sandwich did not reach Quiberon Bay until 22 November, two days after Hawke had caught up with and destroyed the French fleet. Thus Mary Lacy missed participating in the Battle of Quiberon Bay, one of the great naval victories in the history of England.

Hawke’s decisive defeat of the French navy ended the threat of an invasion of England, but the war was still on, and the blockade of the French coast continued. In December the Sandwich was patrolling off Brest when she received Hawke’s orders to join him at Quiberon. Geary dutifully set off amid heavy squalls. First the Sandwich was driven by easterly gales far into the Atlantic. On 15 December she was 480 miles west-northwest of Ushant. Then, as she worked her way back, she was hit by a new gale, this time from the southwest, and was very nearly wrecked on the French coast east of Ushant.19 Finally, on the day after Christmas she staggered into Spithead from where Geary wrote to the Admiralty to explain what in heaven she was doing there:

As the upper works, sides and decks of the Sandwich are very leaky and the oakum worked out of all the waterways of the seams upon every deck, in so much that the officers and ship’s company lay wet, whenever it rains…and having upward of 120 sick on board, 100 of whom are in fevers, the scurvy, fluxes, and consumptions, that the surgeon says there is an absolute necessity of their being sent to the hospital; the beer having been out some days, and having no wine or brandy on board, and in want of sails and stores; I judged it absolutely necessary, as the wind was southerly and I could not recover my station, to bear up for the first port.20

By January 1760 the Sandwich was back on patrol. While Lacy wrote very little about these desperate months, she did describe a shore visit:

As we were stationed off Cape Finisterre and the wind blowing so hard that we could not lie there, we afterwards went and anchored in Quiberon Bay, and when there the officers went frequently on shore; which our master perceiving, obtained leave for me to go with the admiral’s boys when an opportunity offered.… We had a great deal of pleasure in walking about the island in the daytime; but there were very few people in it. When they saw our boat coming on shore, they sent the young women out of the island for fear of our officers; and there were left remaining only two or three old men, and one old woman.

On 12 February the Sandwich, Ramillies, Royal William, and five other ships were sailing together down the channel when “a dreadful hurricane arose which lasted two days.” (Lacy is a month off on the date; she gives it as 12 January.)

By reason of this storm we lost sight of each other, not knowing where we were, and the sea running mountains high, all of us expected to perish. We had seven men drowned, had sprung our main and foremast, and were very nigh the land, but as it pleased God to give us a sight of the danger we were in, we very happily kept clean of the land, and next day went into Plymouth Sound.

When my master went on shore into the yard to report the damage of the ship, I went with him, and we were greatly affected on seeing that only twenty-five men were saved out of seven hundred that were in the Ramillies, which was lost on the fourteenth of January. [She was in fact wrecked on Bolt Head 15 February.]21

The Sandwich was ordered to the shipyard for repairs, which I was glad of, as I always went on shore with my master, who frequented the Sign of the Cross Keys at North Conner.

Lacy was happy to have a respite from the hard months at sea, but she was finding Baker increasingly difficult. His pay was no doubt in arrears, and he was drinking heavily:

When my master was sober, he would sit down and reckon what money he had spent, the thoughts of which ruffled his temper greatly, and at such times I was always the chief object of his resentment; therefore, I was sorry when he was not in liquor.

I now thought that if I could get clear of the ship, I would esteem myself happy, but recollected I had no money; for my master had never paid me any [servants’ wages went to their masters]; and my clothes were made out of old canvas. When I was served with wine, I sold it at two shillings a bottle, and that helped provide me some shirts.

Clothes were important to Lacy; not only her social status but her very existence as a man depended on her attire. She was therefore especially distressed that Baker no longer made the effort to see that she was properly dressed. He did, however, “make many fair promises”:

Amongst others [he promised] that he would bind me out [a carpenter’s] ’prentice and clothe me during that time, though I could never believe it would come to anything.

In the autumn of 1760, while the Sandwich was at Portsmouth, Lacy suffered a renewed attack of her rheumatic complaint and was taken to the hospital. Although she was there for some time, the only treatment she received was to be bled, and no one discovered that she was a woman.22

By the time she was released, the Sandwich had sailed, so she was assigned as a supernumerary in the one-hundred-gun guardship Royal Sovereign, stationed at Spithead.23 This proved a blessing for Lacy. She was now free of the irascible Baker, and soon after she went on board Admiral Geary, newly appointed port admiral of Portsmouth, moved to the Royal Sovereign, together with his servants, who had been friends with Lacy in the Sandwich, and, she remarks, “they were glad to see me.”24

She made new friends as well. A young woman living on board with one of Lacy’s messmates, John Grant, became her close companion:

The young woman and I were very intimate, and as she was exceeding fond of me, we used to play together like young children.… Our messmates believed we were too familiar together, but neither of us regarded their surmises, and if they said anything to her, she told them that if anything like what they suspected had passed between us, the same should be practiced in future.

However, when John Grant became acquainted that she and I were so fond of each other’s company, he began to be somewhat displeased. Nevertheless, he was afraid to take any notice of it lest his messmates should laugh at him. Yet though he seemed to wink at it, he showed her several tokens of his resentment by beating her and otherwise using her very ill, threatening to send her on shore.

One day when Lacy was working on deck she tripped over a cable and fell through an open grate into the hold; her head hit a cask and was badly cut. She was carried to the surgeon’s quarters, and he sewed up the wound:

When I came to myself I was very apprehensive lest the doctor in searching for bruises about my body should have discovered that I was a woman, but it fortunately happened that he being a middle-aged gentleman, he was not very inquisitive, and my messmates being advanced in years, and not so active as young people, did not tumble me about or undress me.

The pain in my head was so exceeding bad that I was almost deprived of my sense, yet notwithstanding my pain, I had a continual fear upon me of being found out, and as I lay in my hammock I was always listening to hear what they said, or whether they had made any discovery. My apprehensions were soon removed, on finding they were as ignorant as before with respect to that particular, so then I continued in my hammock very easy and satisfied.

In addition to her head wound, Lacy was suffering from scurvy, for although the Royal Sovereign while stationed in a home port was supposed to be issued supplementary provisions of fresh meat and vegetables, not enough were provided to prevent the terrible disease from attacking the crew.

Once again Lacy was befriended by a bumboat woman:

Her kindness was the more acceptable as my teeth were grown so loose in my head that I could not eat anything, but by the care of this woman I wanted for nothing and in a short time found myself so much recovered that I could go to the doctor and have my head dressed every day.

Lacy now joined a new mess and became friendly with one of her messmates, the captain of the forecastle, “whose name was Philip M——t——n, who had a notable woman to his wife”:

They were worth money, and lived very happy together on board the ship; and indeed few in our circumstances lived so comfortably as we did. This woman used to wash for me, and also for impressed men as they came on board.

Anyone with spare cash seemed rich to Lacy, even a woman who took in washing.

And if I did any work for these pressed men, my messmates would tell them they must pay for it, because I had no friend in the world to help me;…one would give me a pair of stockings, another breeches, and the rest would supply me with other necessaries.

Next, the boatswain of the Royal Sovereign, Robert Dawkins, who took a fatherly interest in Lacy, asked her into his mess.25 “He being very kind to me,” she wrote, “I lived extremely happy.” Dawkins would continue to be a loyal friend and mentor to her throughout her later years in the navy.

Lacy was also gratified that she was able to attend the school on board “to learn to write and cast accompts.”26 Her only discontent was that for a year and nine months she was not once allowed out of the ship although in sight of Portsmouth. Finally, shortly before Christmas 1762 the crew of the Royal Sovereign were paid off, and Lacy was dismissed:

On this occasion, my joy was so great that I ran up and down, scarcely knowing how to contain myself.

Dawkins invited her to stay at his house in Portsmouth “and [to] eat and drink there.”

The Sandwich had just arrived at Spithead, and the day after Christmas, Lacy went on board to visit Baker. He welcomed her into his cabin and called in her old pal Jeremiah Paine, the gunner’s servant. Baker gave them a bottle of wine and a plum pudding and sent them off by themselves “to tell what had happened to each other since our last parting.”

Baker was about to leave for his home in Chatham and told Lacy that if she would go with him, he would have her apprenticed at Chatham Dockyard. She did not trust him and decided to rejoin the Royal Sovereign, for “the captain of the Royal Sovereign kept me upon the books and paid me, which the carpenter never did to this day.”

She entered as purser’s servant, a position that allowed her to go on shore to run errands for the officers, and she took every opportunity to try to become a shipwright’s apprentice at Portsmouth Dockyard. In the spring of 1763, she succeeded.

Lacy’s success was quite remarkable. It was especially difficult to get an apprenticeship at that time, when the war had just ended; the Treaty of Paris had been signed on 10 February 1763. But apprenticeships were hard to get at any time. It was not skill that mattered, but influence. Traditionally, an apprenticeship was handed down from father to son. While some experience in carpentry was helpful, it was not required; a shipwright’s apprentice needed only to be over the age of sixteen, to be over four feet six inches tall, and to come well recommended.27

The boatswain of the Sandwich told Lacy that Alexander M’Clean (spelled McLean in the muster books), acting carpenter of the Royal William, might take her as his apprentice, and Dawkins encouraged her to apply:

He advised me to agree to the proposal for that it was better to have some trade than none at all and added, “I know him [M’Clean] to be a good-tempered man, and seven years [the length of an apprenticeship] is not for ever, so I would have you go.”

M’Clean offered her the apprenticeship; she accepted and moved her chest and bedding to the Royal William, an eighty-four-gun ship, then in ordinary (out of commission).28

[On the morning of 4 March 1763] my master ordered me to clean myself, and be ready to go ashore with him as he designed to bind me ’prentice that very day.

There was a heavy sea running, and their boat could not get into the regular landing:

[We] were forced to go to the north jetty, where some caulkers’ stages lay alongside, at which place they had driven some nails into the piles (to climb up by)…which were at least sixteen feet high.

My master and the gunner had got safely up, and were walking on; but when I had almost climbed to the top, letting go the rope to take hold of the ringbolt, my foot slipped, and I fell down into the sea; but as soon as I appeared again, the boys upon the stage soon pulled me up…and I recovered myself as well as I could. Presently…my master and the gunner began to miss me; and coming back to see where I was (observing me on the stage) asked the reason why I had been so long in coming.… I then told them that I had fell overboard. On which my master laughed, and sent me to a blacksmith’s shop, where I immediately pulled off my coat and waistcoat to dry myself; after which he [M’Clean]…brought me out of the yard and gave me something hot to drink, to wet the inside; for the outside was sufficiently soaked before.

My master and I went together to wait on the builder to know if he approved of me for an apprentice.… “Why,” said the builder, “I like him very well, for I think he is a stout lad.”

So my master had me entered, but not as a yard servant as he was not allowed to, being only carpenter of the Deptford, a fourth-rate man-of-war. At this time he did duty on board the Royal William [a second-rate ship], the carpenter of which was dead, and he [M’Clean] had some hopes of procuring the place for himself.

M’Clean arranged to have Lacy work under a Mr. Dunn, a quarterman (shipwright and foreman) at the yard.

Mr. Dunn put me under one Mr. Cote to learn my business, who was a very good-tempered man and took great pains to instruct me; he liked me very well and seemed to be greatly delighted to hear me talk.… This affair being thus concluded, my master went and bought me a saw, an ax, and a chisel, which made me very proud.

I was [now] a cadet [assigned] to work one week in the yard and another on board a new ship, the Britannia, just launched.

M’Clean was a gentle, patient master, but like Baker before him, he was a heavy drinker and was constantly in debt, and since the pay of apprentices, like the pay of ship’s servants, went to their masters, Lacy never saw any of her wages and had to scramble for spending money:

When we went to work on board the Niger frigate…, the quarterman, a person whom I worked with, was very kind to me. I had my provisions of the king [a daily food ration], so we made one allowance serve us and sold the other to the purser for a guinea a quarter.… And when I worked in the dockyard, I used to sell my [wood] chips at the gate, and sometimes would carry the bundle to Mr. Dawkins, and was welcome to his house whenever I pleased.

Shipwrights and their apprentices were allowed to sell their wood shavings to the townspeople, who used them for kindling.

M’Clean and his mistress, a boisterous woman who lived with him on board the Royal William, gave many wild parties together with a Mr. Robinson, his wife, and “a deputy purser’s wife.” (The women had all grown up together in the town of Gosport, across the water from Portsmouth.) Lacy was required to act as servant at these parties, a tiresome task after a twelve-hour day at the dockyard, but she had great stamina, and she enjoyed the attention the women paid her:

They sent me for liquor and would often get as drunk as David’s sow, and in the height of these frolics, they would say about me, “Aye, he is, aye, he is, the best boy on board.”

In regard to Mother Robinson, I must acknowledge, she would do any kind office for me. Indeed, I was in general well beloved by the women if by nobody else; and, thank God, greatly respected by my master, so that I lived a quite happy life; and went to work at the yard every day.

When M’Clean sent Lacy to fetch beer on shore, she borrowed the boatswain’s canoe and soon learned to handle it well. One evening her master challenged Lacy to race the canoe against him and three other men in a four-oared boat. He promised to give her a sixpence if she beat them. She won with ease:

I fell a-laughing at them and called out, “Where’s my money, where’s my money!” He told me I should have it, but instead of giving it me, he took us all on shore and spent it among us.

She was shocked when she learned that M’Clean’s mistress was not his wife but the wife of another seaman, then at Greenwich Hospital. Lacy did not, however, let her disapproval affect her friendly relationship with the woman:

My master frequently asked me to dine with him on Sunday if they had any company on board, and then I got a sufficiency [of food], for he would always have me to wait at table. While I was laying the cloth, my mistress would stroke me down the face and say I was a clever fellow. Which expression made me blush.

Frequently after supper my master would ask me to favor them with a song.… Wherefore to divert them I commonly sung them two or three songs, which made them merry until about twelve o’clock, when my master would order me with three more boys to row them to the Hard [the shingle beach at Portsmouth Dockyard backed by a street of taverns], after which they made us a present to buy a little beer, but we made all the haste back [to the ship] we could. [The apprentices were due at the dockyard at six the following morning.]

Getting home to the Royal William from the dockyard was arduous, especially in winter. Lacy left the yard at 6:00 P.M. and then had a two-mile walk to the pier, where she had to shout across the water for a boat from the Royal William to come pick her up:

When the wind was in the east, they could not hear me. Therefore, I was often obliged to stand in the wind and cold until I was almost froze to death, which made me think how happy I would be if my master had a house, for then I should have a good fire to sit by and victuals to eat till the boat came for me.…

I shall next proceed to relate what passed concerning the young woman who lived at Mr. Dawkins’s house, which place I often went to. Being there one evening, he asked me to stay till morning, as he himself was to remain on board all night; and moreover, the maid insisted on my promising to stay there. Having consented, we sat at cards till twelve o’clock, when some young women who spent the evening with us went home. I then asked the maid where I was to lie. She answered there was no place but with her or her mistress. I told her I would lie in her bed. Accordingly she lighted me up to her chamber. Perceiving her forwardness I thought it was no wonder the young men took such liberties with the other sex when they gave them such encouragement; and I am compelled, for the sake of truth, to say this much of the women; but am far from condemning all for the faults of one or two. However, when a young woman allows too much freedom, it induces the men to think they are all alike.

I must confess that if I had been a young man I could not have withstood the temptations which this young person laid in my way, for she was so fond of me that I was ever at her tongue’s end; which was the reason her master and mistress watched her so narrowly. In short, there was nothing I could ask that she would refuse; and, to make me the more sensible of it, my shirts were washed and prepared for me in the very best manner she was able.

At this point M’Clean must have received some of his back wages, for to Lacy’s delight, he was able to rent a house on shore. There Lacy and another apprentice, John Lyons, shared a bed in a room on the upper floor. At first Lacy worried that Lyons would discover that she was a woman, but he had less energy than she and went to bed “as soon as he came home from dock… [and] was no sooner abed but asleep.”

Kindly M’Clean, with a bit of extra cash, told Lacy, “I should have a new suit of clothes and not go so shabby as I was”:

The tailor came as he was directed, and my master gave me my choice of the color, for which I thanked him and fixed upon a blue which he seemed well pleased with; and I was not a little proud to think that I should have good and decent apparel to appear in, as I could then walk out on Sundays with the young women.

Lacy and her friend Edward Turner, who was living in the Royal William, had been flirting with a group of friendly young women whom Lacy had met when they came to the dockyard to collect chips. Turner invited Lacy to a party in their honor:

We had a leg of mutton and turnips and a fine plum pudding provided, with plenty of gin and strong beer, which I considered as a grand entertainment for me and the young ladies.… We were very merry with our new acquaintances, and I soon found that Vobbleton Street was the place of their residence.

It was only when Turner and Lacy saw the girls home that Lacy realized that this “couple of merry girls” were not the innocents she had supposed:

This street in Portsmouth town is inhabited with divers classes of people, so that I soon found what sort of company I was in.

One evening when M’Clean was away, his mistress returned home from a drunken evening in Gosport and brought with her a group of revelers, including a waterman—the one, perhaps, who brought the group back across the harbor. (A waterman was the equivalent of today’s taxi driver, only his taxi was a boat.) Upon their arrival she hailed Lacy, who had retired to her bed upstairs:

She soon called me and I told her I was coming down; which I did without the knowledge of my bedfellow.… I found that she wanted some beer, for she said she was thirsty. Accordingly, I went and brought a pot of ringwood [a kind of ale], and, it being summertime, she sat at the door to drink it, over against which there being a wheelbarrow, I went and sat down upon it. My mistress observing me, came and placed herself in my lap, stroking me down the face, telling the waterman what she would do for me, so that the people present could not forbear laughing to see her sit in such a young boy’s lap as she thought I was. However, she had not been long in this situation before my master came home, and passed by her as she sat there; but taking no notice that he saw us, went in doors.

And indeed I was very much frightened lest he should beat me, but I thought he could not justly be angry with me, for it was all her own fault.

I went then to try the door to discover if my master had locked it… I told her the door was locked and that we must both lie in the street. Upon which she said she would go back to Gosport, and that I should go along with her.

As we were thus talking together under the window, my master, overhearing her say she would set off for Gosport,…threw up the window and soused us all over with a chamber pot full of water, which made me fall into such a fit of laughter that my sides were ready to burst…to see what a pickle she was in.

While the woman was mopping herself off, Lacy tried the door again and, finding it was not locked after all, slipped into the house:

I immediately took off my shoes and stockings, ran upstairs, pulled my bedfellow out of his place, and got into it myself; for I supposed if my master came up to thrash me, he would lay hold of my bedfellow first, and then I should have time to get away. However, as good luck would have it, he did not concern himself with me but vented his anger on my mistress when she came in, telling her she might go to the waterman again, and would not let her come to bed.

In the morning my bedfellow John Lyons wondered how he came into my place in the bed, for he had heard nothing about the matter, being such a sound sleeper. We both went as usual to work at the dock.

Not long after this incident, M’Clean was arrested as a debtor and carried off to the jail at Winchester. Lacy was greatly upset to hear of her poor master’s arrest, and twice she went all the way to Winchester to visit him. The first time, she walked there and back.

M’Clean’s mistress was less grieved:

[She] began stripping the house and carrying the furniture to the pawnbroker’s, which indeed was the only method that could be taken to procure us some victuals.… My mistress seldom lay at home above a night in the week and went abroad in the morning, so that for the remaining part of the week, when I came home from work at night, [I] was obliged to go from house to house [to get food] as it were in my master’s name.

M’Clean’s mistress, despite her straitened finances, found enough money to continue to carouse, and sometimes she inveigled Lacy into going with her “to Gosport into those lewd houses in South Street, where I was obliged to be very free with the girls.” One night Lacy’s mistress took her to the theater together with “a young woman called Sarah How, who indeed was a very handsome girl”:

From that time the above Sarah How became very free and intimate with me; nor did I ever go to town without calling to see her, when we walked out together.

After several months of imprisonment, M’Clean was released under an arrangement that required him to pay over all his assets, including his apprentices, to his debtors. He was also obliged to go to sea, where he was less likely to run up more debts. He turned Lacy over to a Mr. Aulquier, who was continuously drunk and brawling with his wife. M’Clean then joined the Africa and disappeared from Lacy’s life. He left in 1765, and for the remaining five and a half years of her apprenticeship, Lacy was passed from one drunken, debt-ridden master to another:

I had not been long with him [Aulquier] before he turned me over to another man to pay his debts, and when I had worked that out, was again turned over to a third, so that being shifted from one to another, I had neither clothes to my back nor shoes or stockings to my feet. I was frequently, even in the dead of winter, obliged to go to the dockyard barefooted.

Throughout this period Lacy’s one comfort was that she continued to prove a great success with the ladies. “On Shrove Tuesday in the year 1766,” Betsy, a former girlfriend, asked her to a dance. Lacy accepted, although Dawkins had warned her that Miss Betsy was not a proper young lady. After the party, however, fearing that Dawkins would hear that she had renewed this unsuitable acquaintanceship, Lacy decided that she would not see Betsy again. But her resolve did not last long:

One day, as I was going down the Common in Union Street, she [Betsy] happened to stand at a door; and seeing me, said, “Will, I thought you was dead.”

“Why so?” returned I. “Did you send anybody to kill me?”

“No,” replied she, “but I thought I should never see you any more.”

“Well,” said I, “you are welcome to think so still, if you please, but I must be going.”

“What!” said she. “You are in a great hurry now to be gone; if you was along with that Gosport girl you would not be in such haste to leave her.”

I said, “I am not in such a hurry to be gone from your company, Betsy; what makes you think so?”

After this little chat, though with some seeming reserve on both sides, she asked if I would come in. I went in and sat down, and then asked her if she would come next Sunday to Gosport and drink tea. She told me she would. Thus it was all made up again.

Lacy continued to see Betsy until Dawkins learned of the affair and questioned her about it. “William,” he said, “I am sorry you will walk out with her when I have told you what she is.” Lacy staunchly denied everything:

“Well, sir,” said I, “I am much obliged to you for your advice, but as for keeping her company, I do not; nor do I know that I shall ever speak to her again.”

This matter passed over for some time, and by giving attention to my work I thought little or nothing about things of this kind. However, one evening my fellow servant Sarah Chase began talking as we were sitting together about sweethearts and said to me in a joking manner, “I think you have lost your intended.”

“Well,” replied I, “I must be content.”

She said, “There are more in the world to be had.”

“Aye,” replied I, “when one is gone, another will come.”

“For my part,” added she, “I have got never a one.”

“Well,” said I, “suppose you and I were to keep company together?”

“You and I,” answered she, “will consider of it.”

From that time on, Lacy and Sarah Chase saw a great deal of one another:

I had not yet served quite three years of my time; nevertheless, it was agreed that neither of us should walk out with any other person without the mutual consent of each other. Notwithstanding this agreement, if she saw me talking to any young woman, she was immediately fired with jealousy and could scarce command her temper. This I did sometimes to try her. However, we were very intimate together.

And to give me a farther proof of her affection, she would frequently come down to the place where the boat landed [to bring the dockworkers from their ships] to see me, which made the people believe we should soon be married. One man observed, “Well done, Chandler, you come on very well.” Another said that I should be a cuckold before I had long been married for that she was too large for me, as I should make but a little man.

Lacy was fond of Sarah but could not resist flirting with other young women:

Sarah began to have a very suspicious opinion of me, on observing I spoke to another girl, for one evening when I went indoors to ask her for some supper, she looked at me with a countenance that bespoke a mixture of jealousy and anger. It then came into my mind that there would soon be terrible work. Whereupon I asked what was the matter with her. She told me to go to the squint-eyed girl and inquire the matter there. “Very well,” said I, “so I can.”

From hence I soon knew what was the ground of all. It seems the taphouse woman had been telling her more of this affair at large, which brought me into a great difficulty; and indeed I lived a very disagreeable life at home, especially since I could not get my victuals as before.

Sarah soon forgave Lacy, and they continued their courtship.

In 1767 Lacy got leave to visit her parents and sailed in a naval vessel to the Downs, then traveled overland to Ash. She was now twenty-seven and had not been home since running away at nineteen:

I found all the family very well; and took that opportunity of satisfying their earnest expectations by recounting the various turns of fortune I had met with and gone through during an absence of almost eight years.

Lacy does not mention their feelings about her living as a man. She apparently maintained her male role in public during the visit, so that only the family and a few close friends knew who the visiting sailor really was.

There is an interjection here that harks back to Lacy’s teenage infatuation with her dancing partner:

The young man on whose account I at first left my parents had frequently caused inquiry to be made when I was to come home, expressing a great desire to see me, but I had no inclination to receive any visits from him.

Why he should want to see her at this point when he had expressed no special interest in her when they had met eight years earlier is not explained.

Not long after Lacy returned to Portsmouth, a frightening episode occurred. A Mrs. Low, a close friend of the Lacy family in Ash who knew Mary’s secret, moved to Portsmouth, and although she had promised never to reveal Lacy’s true identity, she spread the rumor to anyone who would listen that William Chandler was a woman. Lacy, however, had no inkling of her perfidy:

[One morning when] I went to the dock it was whispered about that I was a woman, which threw me into a most terrible fright, believing that some of the boys were going to search me. It was now much about breakfast time when, coming on shore in order to go to my chest for my breakfast, two men of our company called and said they wanted to speak to me. I went to them.

“What think you, Chandler,” one of them said. “The people will have it that you are a woman!” Which struck me with such a panic that I knew not what to say. However, I had the presence of mind to laugh it off, as if it was not worth notice.

On going to my chest again, I perceived several apprentices waiting who wanted to search me, but I took care not to run lest that should increase their suspicion. Hereupon one Mr. Penny of our company came up and asked them what they meant by surrounding me in that manner, telling them at the same time that the first person that offered to touch me would not only be drubbed by him, but [that he] would carry him before the builder afterwards, which made them all sheer off.…

However, when I had done work, the man whose name was Corbin and his mate who taught me my business came and told me in a serious manner that I must go with them to be searched. “For if you don’t,” said they, “you will be overhauled by the boys.”

Indeed, I knew not what to do in this case, but I considered that they were very sober men, and that it was safer to trust them than expose myself to the rudeness of the boys. They put the question very seriously, which I as ingenuously answered, though it made me cry so that I could scarce speak, at which declaration of mine in plainly telling them that I was a woman, they seemed greatly surprised and offered to take their oaths of secrecy.

When they went back, the people asked them if it was true what they had heard.

“No,” said they, “he is a man-and-a-half to a great many.”

“Aye,” said one, “I thought Chandler could not be so great with his mistress if he was not a man. I’m sure she would not have brought him to the point if he was not so.”

And another said, “I’m sure he’s no girl; if he was, he would not have gone after so many [women] for nothing and would have soon been found out.”

For such talk as this among the men, in a day or two the matter quite dropped; yet now and then they would say, “I wonder how it should come into the heads of the people to think that Chandler was a girl; I am sure there is not the least appearance of it in the make or shape of him.”…

My girl at Gosport [Sarah Chase] had heard it, but could not believe it.

Several years passed before Lacy discovered that it was Mrs. Low who had betrayed her, and by that time she was lodging at Mrs. Low’s house “in the Tree Rope Walk, on Portsmouth Common”:

As soon as I heard that Mrs. Low had told everybody who I was, I was ready to break my heart.… I thought she was the best friend I had.… Indeed, I esteemed myself happy in having met a person I could freely unbosom myself to.

Lacy not only had to find a new place to live, but from that time onward she was also tortured by fears that her gender would be discovered.

In the spring of 1770 Mary Lacy received her certificate as a shipwright:

On the last day before my time expired, being at work upon the Pallas frigate, Sarah came and invited me to breakfast with her the next morning, which I did. Having afterwards cleaned myself, I went to the builder’s office and told him it was the last day of my time and hoped he had no objection against my certificate’s being allowed me.… He then called his clerk and ordered him to prepare a certificate, which he accordingly did; after which I went to each of the proper persons, who readily signed it. I then carried the certificate to the Clerk of the Cheque’s office, where I was entered as a man.

She had at last acquired the respected position she had worked toward for seven years; she was free from cruel masters, and she actually received a living wage, although the navy was slow to pay.29 Tragically, however, she was to have little time to enjoy her new status.

After a major fire in the dockyard on 27 July 1770—Lacy gives the date as 16 May—all the yard workers were required to work overtime; they worked as much as five hours in addition to their twelve-hour day, and the strain caused Lacy’s rheumatism to return.30 The anguished way she writes about her battle against her illness reveals how desperate she was to maintain her role as a shipwright:

[When the overtime hours were reduced] I was not sorry…as I was almost spent with working so close, for in a little time afterwards I was seized with so bad a swelling in my thighs that I was not able to walk, and was unwilling the doctor should look at it lest he should find me out. I therefore sent for the quarterman to answer for me that I was sick, which he accordingly did, and I continued a week before I was able to go into the yard again and was then incapable of doing any work.

When Lacy recovered from this attack she was ordered to work in various ships anchored at Spithead, where she had to stay on board day and night:

We were in as bad a situation as before, having no other place to lie but the softest plank we could find; so that such a wretched accommodation during that time made me catch cold again in my thighs and occasioned my illness to return. However, I soon mended.…

A short time after this I was, on account of lameness, forced to go upon the doctor’s list for a fortnight, but thank God I got the better of this and went to work again, though continually apprehensive of being surprised unawares, for I did not know the particular persons my false friend had betrayed me to.

Soon afterwards our company was ordered to tear up an old forty-gun ship, which was so very difficult to take to pieces that I strained my loins in the attempt, the effects of which I felt very sensibly at night when I went home, for I could hardly stand and had no appetite to my victuals. But notwithstanding my legs would scarce support me, I continued working till the ship was quite demolished, and then we were ordered on board the Sandwich to bring on her waling [timbers bolted to the sides of a ship], which was very heavy.

This increased my weakness to such a degree that the going to work proved very irksome to me, insomuch that everybody wondered what was the matter.

However, I still continued my labor till want of strength obliged me to quit it. And then I went to the doctor’s shop and told him I had strained my loins, which disabled me from working. Whereupon he gave me something which he thought would relieve me. I took it, but had it not been for the infinite mercy of God toward me, I should certainly have been killed by it, the medicine being altogether improper for my complaint. In consequence whereof, instead of growing better I became every day worse than the former, which made me think I could not live long.

However, in process of time my complaint abated, but not so as to enable me to work as I had done before, nor could I carry the same burthens as usual, which made me very uneasy.

Lacy slowly accepted the fact that she was going to have to resign from the dockyard:

While I continued in this weak condition, I imagined that if I could go down to Kent [to her home in Ash] I might get a friend to help me out of the [dock]yard, but getting somewhat better, I went to work as well as I could.

The loss of my father and mother likewise greatly aggravated my concern, and I began to think of endeavoring to obtain liberty of the builder to go into Kent for a fortnight, which he readily granted.

Lacy gives no details of her parents’ deaths. It is sad that they died just when she could at last expect their approval of her status and when she could send some money home. In the past she had always ended her letters to them “Your undutiful daughter,” but a letter she wrote soon after she became a shipwright was signed “Your dutiful daughter.”

She got leave to go to Ash, where she hoped to get help from family friends in arranging for a disability pension from the navy, and a Mrs. Deverton contacted her brother Mr. Richardson in London, asking him to aid Lacy in petitioning the Admiralty, whose offices were in London. Richardson—who had known Lacy’s family for some years and was apparently aware that Lacy was a woman—was a man of some prominence, perhaps a solicitor:

He sent me word he could not do anything for me at that time because all the gentlemen [at the Admiralty?] were out of town, but that in a month’s time he would write and let me know further.

Lacy returned to work “but was in a short time after taken as ill as ever.

Toward the close of the year 1771, Richardson invited Lacy to come stay with him and his wife at their house in Kensington, just west of London, while he helped her through the lengthy procedure of applying for a pension:

This news in a few days gave a happy turn to my disorder and almost restored me to health, so that I embraced the first opportunity of going over to Gosport to take leave of them all [her various girlfriends] and [then] went directly home to make myself ready to go with the coach [to London].

My parting with the young women occasioned a scene of great perplexity and distress; and indeed one of them was ready to break her heart. This was poor Sarah, whose pitiable case affected me very much. However, I set off from Portsmouth the second day of December 1771 and reached Kensington the next day.

The complicated process of petitioning for a pension could take months, and it was not always successful, even for those with the severest need. It may have been Richardson who suggested that Lacy apply under her own name, and probably because the case of a woman petitioner caught the attention of the lords of the Admiralty, the pension was granted within two months. On Tuesday, 28 January 1772, the Admiralty minutes report:

A Petition was read from Mary Lacey [sic] setting forth that in the Year 1759 she disguised herself in Men’s Cloaths and enter’d on board His Majts Fleet, where having served til the end of the War, she bound herself apprentice to the Carpenter of the Royal William and having served Seven Years, then enter’d as a Shipwright in Portsmouth Yard where she has continued ever since; but that finding her health and constitution impaired by so laborious an Employment, she is obliged to give it up for the future, and therefore, praying some Allowance for her Support during the remainder of her life:

Resolved, in consideration of the particular Circumstances attending this Woman’s case, the truth of which has been attested by the Commissioner of the Yard at Portsmouth, that she be allowed a Pension equal to that granted to Superannuated Shipwrights.31

The Navy Board’s Abstract of Letters gives the same information, except that it states that “she was commonly called Mrs. Chandler.”32 She was granted twenty pounds a year.

The last two paragraphs of Lacy’s book introduce a most surprising event: her marriage to a certain Mr. Slade. These paragraphs seem to be tacked on to her narrative in order to give it a storybook ending: and so they were married and lived happily ever after. It also reassures the reader that, when all is said and done, Mary Lacy was heterosexual: