Faded glory. That’s how I’d describe Mama’s apartment. At least, that’s what I’d say when I was feeling generous. When I wasn’t, I’d say it was a dilapidated piece of shit. But Mama loved it. Loved her seven big rooms, all sprouting from that tunnel of a hallway like branches from a tree. High ceilings, hardwood floors, and a maid’s quarters. Not really a living room, but a parlor and a dining room, with nearly floor-to-ceiling windows. Sounds grand, don’t it?

Built in 1910, that place was meant for the wealthy. But that was then and this was now and it was old—past old. It exuded sadness and disappointment. It stunk of mildew and dust, of ancient asbestos and long-dead vermin. The high ceilings leaked streams of filthy water, the tall walls were buckled, and the floor was treacherous with slivers.

Mama wasn’t blind to all the problems. She simply didn’t care. The place had been her home for nearly forty years. She had grown up during the Depression, dirt poor and hungry, in a rambling broken-down farmhouse. Determined to get ahead, she left Virginia when she was fifteen and grabbed a Greyhound bus for New York. That was in 1932, when the whole country was still struggling and chances for a colored girl with a ninth-grade education were next to nil. She had gone to work in Long Island, as a maid in the homes of moneyed white folk. Not often, but sometimes, she would talk about their grand homes. And sometimes I’d wonder: did this place of faded grandeur remind her of the homes she’d worked in? Maybe in her eyes, the dull floors still shone and the sagging walls were still ramrod straight.

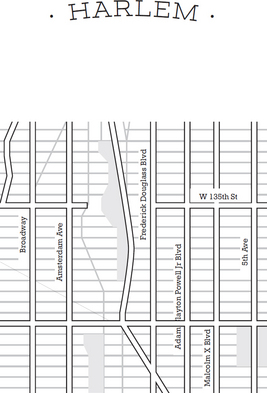

Mama was ninety years old. She had lived in Harlem for some seventy-odd years, and she was still proud to be there, in the legendary mecca of black folk. Nowadays, a lot of black Harlemites were heading back down South, where life was slower and money went further. But you couldn’t tell Mama that. She still believed that Harlem was the only place to be.

She was especially proud to be in Hamilton Heights. It was a historic landmarked district, with rows of stately townhouses and stone terraces. It was home to an ethnically diverse community of actors, artists, architects, professors, and other intellectual bohemians. Certainly, parts of it were lovely.

“This is one of the nicest neighborhoods in all New York City,” Mama would say.

Then I’d say, “But I’m not complaining about the neighborhood. It’s this building.”

And that, of course, was a bald-faced lie. ’Cause I was most definitely complaining about both.

The gentrification that had hit Central and East Harlem had pretty much left West Harlem alone. At least our little part of it. That stretch along 135th and 145th Streets, between Broadway and Amsterdam? It was sad. Cheap landlords, run-down tenements. There were a couple of good restaurants along Broadway, but they were probably going to close soon. The atmosphere of an open-air drug market had certainly calmed down, but sometimes it felt like the dealing had just gone underground.

Then, there was the other Hamilton Heights. It was gorgeous. Convent Avenue, Hamilton Terrace, Sugar Hill: they were stunning—but they had always been stunning. Until fairly recently, they’d been among Harlem’s best-kept secrets. Even with as well-known a place as City College being on Convent Avenue, Hamilton Terrace, for example, escaped general notice. It was a forgotten enclave. A city apart. Even the air over there was different.

Over there. That’s how I thought of it. That was over there. And this was over here, where the people were holding on by the skin of their teeth.

“Well, if you don’t like it, leave,” Mama would say.

And I would sigh. Because we both knew I couldn’t. Not without a decent job and not without her. My dream was to earn enough to get us both out of there, but she didn’t want to go.

“This is my home,” she’d say. “When I die, it’ll be yours, and you can do with it whatever you damn well please. But for now, it’s mine, and the only way I’m leaving is when I leave this world.”

“Don’t talk like that.”

“Why not? It’s gotta happen sometime,” she’d say, and then add, with a rueful smile, “It’s got to.”

She had a weak heart—weak, but determined. You could see it on her echocardiograph how her heart would hesitate, then give a little flutter and pump, hesitate, then flutter and pump. It amazed her doctors, and it worried me. But it only bewildered Mama. Sometimes, I’d hear her in her room, crying. Why did she have to keep on living when so many of her friends were gone? Why?

It wasn’t just a matter of being left behind. It was that she couldn’t do what she loved doing. Not anymore. She couldn’t entertain, give her dinner parties. She was known for her sweet potato pie. Everyone in the building had gotten one at one time or another, usually to welcome them or congratulate them, or just to make them feel better. She loved cooking and going down the hill to the grocery store. But of late, she had become too weak to do either. She had taken to sitting in her room, in the dark, for hours.

I blamed the apartment. It was killing her.

It wasn’t just the dirt, the stench, and the roaches. It wasn’t just the bathroom ceiling that collapsed without fail every six months, showering down filthy rocks, rotten wood, and cracked plaster.

It was the mice.

Oh, the mice!

They were everywhere. You could hear them skittering through the walls, see them scampering across the floor. Our living room was their highway. One evening, as I rested on the couch, I set a glass of water on the floor. Next thing I knew, a mouse was raised up on all fours, taking a sip. One day Mama left a sweet potato pie on the stovetop to cool. She turned to the sink to wash a spatula and turned back just in time to see a mouse making a beeline for her pie. Man, oh, man, was he making tracks! But he sure put the brakes on when he saw her. She stared into his beady little eyes and he stared right back. Who was going to make the next move?

She was fast, but he was faster. She went to whack him with the spatula, but with a flick of his tail, he was gone. Dove right into the stove, she said, down through an eye. “That sucker jumped right into a warm oven, like it was home. Made me wonder what else was hiding in there.”

She told me the story over dinner. That pie had gone right into the garbage, and dinner that night had come out of a can.

Disappointed, I said, “If you won’t move, then at least do something about the mice.”

She knew where I was going.

“I’m not gonna get no cats. I hate cats. Just hate ’em. They are not coming into this house.”

“But—”

“This is my house,” she reminded me. “Mine! Do you hear? And I say no cats.”

And that was that.

Until Martin Milford moved in. Of course, at the time, we didn’t know nothing about no Martin Milford. All we knew was that the walls of our apartment were suddenly vibrating and a river of mice was coursing through our walls. The place echoed with the sound of a buzz saw. I couldn’t tell whether it was coming from upstairs or downstairs. I tried to ignore the commotion at first, but then it got so bad, I had to check it out. I ran upstairs to the apartment above us. Nothing unusual was going on there, so I headed downstairs to the ground floor.

The door to the apartment below us was open and I could see that someone was doing some major renovations.

That someone would turn out to be Milford. He was tall and lanky, with watery blue eyes, thin blonde hair and a short scraggly beard. Reminded me of an aging hippie. He had on a dingy white T-shirt and dust-covered jeans, and he was using an electric saw to rip out a wall. He stopped when he saw me, unhooked his dust mask. As soon as he heard that I was his neighbor, he smiled and shook my hand. I had been prepared to fuss, but he disarmed me by being so friendly and all. He immediately started telling me about himself.

Was a photographer, he said, a freelancer. Had moved up from “below Ninety-Sixth Street.”

One of those, I thought. Didn’t think Harlem was good enough ’til loss of a job or income forced him to reconsider.

“Look here,” I said, gesturing toward his saw, “you—”

“I am so glad I found this place. Been looking for a real long time.”

“I understand, but—”

“Lived on the street for a while. When I got this place, I couldn’t believe it. Just hadn’t had no luck, you know?”

Yeah, I knew. I was barely making ends meet, going from one survival job to another. It was the height of the so-called Great Recession and I was earning just enough to cover expenses.

“Look—” I began again.

“Sold my Harley to get the down payment.” He shook his head. “Never thought I’d have to do that. It’s just that things got so bad, I …”

“I know, I know,” I said, finding it hard to stay angry. “But look here, I wanted to—”

“Landlord said he’d give me a good deal if I took this place as is. It’s a bit more work than I thought it would be, but I’m enjoying it. Living room’s gonna make a great studio.”

I glanced down his hallway. He had all the room doors open. The sunlight was streaming in. He’d already relaid the hallway floor. The new planks gleamed in the late afternoon light. I had to admit, he was doing good work, the kind of work I wished we could do on our place. I looked back at him. He seemed like a nice enough man, and I knew what it was like to have dreams.

“You’re going to do a whole lot more?”

“Naw, nearly finished. I think I’ll be done in just about a week. Why?”

I just waved it away. “Never mind.”

The renovations didn’t go on for another week, or two or three, but four. A whole damn month.

I tried to talk to him a couple times, but each time he grew less and less sympathetic. “The noise is driving us crazy,” I would say. “The dust is coming up in puffs through the floorboards. And the mice. The noise isn’t just driving us crazy; it’s driving them crazy, too. They’re all over us.”

“But you can’t blame me if you’ve got mice.”

“I said—”

“I know what you said. You can’t tell me what to do in my apartment. I’m not stopping my renovations just for you.”

I had told myself to keep a cool head, so I bit back what I really wanted to say and stayed polite. “Look, I don’t want to fight. Just tell me, how much longer?”

“For however long it takes,” he said and slammed the door in my face.

I knew he didn’t have a permit for the changes he was making, and I thought about reporting him more than once. The city inspectors would’ve shut him down but quick. If it had been the landlord, I would’ve dropped a dime in a minute. But you don’t do that to another tenant. Not in Harlem. Tenants should always stick together.

So Mama and I swallowed our aggravation over the noise—and the mice. Clearly, Milford’s renovations were driving the mice to literally climb the walls. Their population had doubled. And they were having babies. You could hear them squealing. I went out and bought rat poison, but then Mama said not to use it. The mice would eat it, crawl into some little hole and die. Then their rotting little corpses would stink up the place.

Good grief!

We didn’t even bother with mousetraps. We’d tried them before. Either the mice weren’t interested, or if they were—and this was the worst part—they got caught in them, but didn’t die. You’d walk into the kitchen in the middle of the night and find one of them very much alive and kicking. And that meant you’d have to kill it yourself. Not for Mama, and certainly not for me.

So, I kept pushing the idea of getting a cat, but Mama held out, No, No, NO!

That is, until the day she found mice in her bedroom, playing on her sheets. Suddenly, she didn’t want just one cat, but two.

The next day, I got them, rescues from the animal shelter. Dizzy and Gillespie. They were the cutest little things. Fast, too. And hungry. Those mice were gone within days. Fine with me.

Fine with Mama.

But not fine with Milford.

Soon, we heard a knocking on our door. Milford looked exhausted.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

He had mice, he said. Not just a few, but hordes of them.

“They got into my bedroom closet, my kitchen cabinets. I found a dead one in my bathtub the other day. And yesterday, I was trying to do a photo shoot, you know, in the living room, and a mouse ran right across the client’s feet. She walked out, and now she won’t pay me.”

“I’m sorry to hear that, but—”

“So, I’m wondering if you guys were doing something—”

His gaze dropped and his eyes widened. I glanced down and saw Dizzy and Gillespie, standing guard at my ankles, staring up at him.

“Cats!” Milford said.

“Obviously.”

“You’ve got to get rid of them.”

“S’cuse me?”

“I said, you have got to get of those … things.”

I couldn’t believe his nerve. “Ain’t happening. They’re my mother’s cats, and they are here to stay.”

And they really had become her cats. I had been the one to push for them, but she was the one they took to. And she took to them. It was Mama who came up with the idea of naming them Dizzy and Gillespie, after the great jazz musician of the 1940s. It was Mama those two cats cuddled up to at night. It was her they loved, and it was clear that she loved them. She had found renewed strength to go down the hallway to the kitchen. She couldn’t stand long enough to cook, but she could feed her cats, all the time fussing about “how you’ve got to feed them just right.” Then she would come sit in the living room with me and watch them play and get into mischief. She would laugh and clap her hands! She said she used to be afraid of cats, but she wasn’t afraid no more.

“They something else,” she said. “So pretty, and so sharp! Why, they understand everything I say!”

We’d tried every medicine under the sun to bring down Mama’s blood pressure; they’d all failed or caused bad side effects. Dizzy and Gillespie got it down to normal in a week. Between the mischief that made her laugh, the purring that soothed her nerves, and the security of knowing she could sleep in a mouse-free bed, those cats had brought Mama more joy and better health than I could’ve imagined.

So, no. We were not going to get rid of them.

“Why don’t you get cats of your own?”

“Hell, no!”

He said he was going to take it to the landlord.

“Do that,” I said. “He don’t care. Saves him the cost of hiring an exterminator.”

Then I shut the door and gave Dizzy and Gillespie good ear rubs.

Mama wanted to know what was going on.

“I thought you said he was a nice man,” she said when I told her.

I shrugged. “Seemed like it.”

She sighed. “If he’s the type of folks moving up to Harlem these days, then …” Her voice trailed away.

“Then what? You wouldn’t be saying you want to move, would you?”

“No,” she said. “It’s them I’m talking about. They the ones gonna have to go.”

Two days later, Milford was back at our door. Mama was the one who answered.

I watched from down the hall as he bowed and handed her a bouquet of flowers. “I’m sorry,” he said, “I don’t know what was wrong with me. I had no right to say what I said.”

Mama accepted the apology, and the flowers. After he left, she turned to me and said, “Well, well, well. I guess he’s not so bad after all.”

“C’mon, Mama. You know what happened as much as I do.”

“The landlord gave him a piece of his mind?”

“Of course, he did.”

The next few days were quiet. I put Milford out of my mind and went back to worrying about work. For the time being, my concerns about Mama were eased. Her health had stabilized. Her depression had lifted. She talked about Dizzy and Gillespie all the time, about how sweet they were, how smart they were, how they were just about the best cats of all time.

Then one day I came home from another useless interview and found Mama sitting in the living room, holding Dizzy. I knew right away that something was wrong. Dizzy was real still and, Gillespie was sitting at Mama’s feet, meowing.

“Mama?” I put a hand on her shoulder.

“She’s gone,” Mama said.

Dizzy’s little mouth was open and her body twisted. She must’ve died in agony.

“What happened?”

“I don’t know.” She looked up at me, and the grief in her eyes made my heart constrict. “One minute she was healthy and happy, as frisky as you please. The next, she was having a fit of some kind. Then she started vomiting, and before I could do anything, she was … like this.”

Dizzy was still so small she fit into a boot box.

“Don’t put her in the garbage,” Mama said.

“I wouldn’t do that. I’ll take her to the vet tomorrow.”

“We’ll go together.”

“Okay.”

But the next day when I came home to pick up Mama, she was in no state to go anywhere. She was sitting in her bedroom, and this time it was Gillespie she held.

Mama had taken Dizzy’s death hard enough, but Gillespie’s really floored her. She was heartbroken.

I couldn’t understand it. “Two healthy cats don’t just up and die like that.” I asked her if she wanted the vet to do a necropsy, but she said not to. “Leave well enough alone.”

I said I would, but I couldn’t. I asked the vet what had gone wrong. She had a one-word answer.

“Strychnine.”

In other words, rat poison.

I was stricken. This was my fault. I told Mama, “They must’ve gotten ahold of what I bought. I’m so sorry. I thought I put it all away. But I guess I didn’t.”

I hoped for a scolding word, but she said nothing, just sat there wrapped with grief. Over the next two days, she went back to sitting in the dark. “This is twice this has happened to me,” she said. “I ain’t never gonna let it happen again.”

She wouldn’t say what she meant by that. Just told me to clear out everything belonging to the cats.

“I don’t think that’s a good idea,” I said. “Even if Dizzy and Gillespie are gone, their smell might keep the mice away, at least for a little while.”

But her mind was made up.

“Get rid of it. All of it. Then scrub the place clean.”

So I did.

Within days the mice were back. Mama’s depression deepened and her blood pressure soared.

The doctor was worried. “If we don’t do something, then …” He let silence fill the blank. “And it could happen soon, real soon.”

I tried to talk to her about getting another pair of cats, but she wouldn’t hear of it.

“No,” she shook her head. “Never again.”

I didn’t know what to do, so I put my arms around her and hugged her. “It’s gonna be okay, Mama. It’s gonna be okay.”

For a several seconds, we just held each other, sitting in her room. Then she said something.

“What?” I asked.

Her voice was hoarse. “It was my fault,” she whispered, “my fault they died.”

“What?”

“It was me.”

I shook my head. “I don’t understand.”

She didn’t answer.

Then understanding dawned. I covered my mouth in shock. She had killed them. She had killed Dizzy and Gillespie. I couldn’t believe it. I didn’t want to believe it. But then I searched her eyes, and saw not just the grief, but the guilt.

“You—? It was you? But why? I thought you loved them. I—”

“I don’t know.” She shook her head. “I don’t why I—I just …” Her eyes pleaded with me. “I think I just … I just wanted to be a good neighbor.”

“What does that mean?”

But she couldn’t answer. She was gone, withdrawn into her own world.

“Mama?”

She turned from me, wringing her hands.

“I … I know I can’t bring them back,” she said, “but I’m gonna make it right. I’m gonna make it right.” She kept saying that. She wouldn’t talk to me except to say that.

I was so hurt and angry, I didn’t know what to do. How could she have done something like that—that hateful? Kill two helpless cats? Cats she loved? And how could she ever think she could make it right? I didn’t want to be around her. I had to get out of there. I grabbed up my coat and my bag, fled down the hall and out the door.

I walked for hours, wondering what I was doing with my life. And I didn’t go home that night. I stayed with a friend, trying to swallow the anger, trying to understand. I so wanted to move out. But I was trapped. I couldn’t afford another apartment, and she couldn’t live on her own. We were stuck in that apartment together, with the stench and the mold and the mice.

I took another step back. Here I was, a grown woman, and all I could think about was running away from home. How crazy was that? All night I thought about it. By morning, I was exhausted, but I had decided.

No matter what, she was my mother and I loved her. As long as she was staying, so was I.

Coming up the hill from the train station, I saw police cars, an ambulance, and a crowd standing outside our building. It was my mother. I just knew it was my mother. She had fallen or had some other mishap, and I hadn’t been there to help her.

I ran the last few yards to the house and pushed my way through. The lobby was packed with neighbors and cops telling them to get back.

“You’ve gotta let me through,” I cried. “I’m her daughter! Her daughter!”

The cop gave me a strange look and asked me what apartment I lived in.

“Twenty-four.”

“That’s not the one.” He jerked his thumb over his shoulder, and that’s when I saw what I would’ve seen to begin with if I hadn’t been so panicked.

Milford’s apartment door stood open. A paramedic came out, stripping off his rubber gloves. He said something to one of the cops. I couldn’t read his lips. I didn’t have to. His expression said it all.

“What happened?” I asked the cop.

“Did you know him?”

“Sort of. I mean, yeah. He’s my neighbor.” I glanced back at the open apartment door. They were carrying Milford out on a stretcher, in a body bag.

I couldn’t believe it. Milford, dead?

“What happened?” I asked again.

“We don’t know yet. But look,” he said, “why don’t you give me your name and apartment number in case we need to talk to the neighbors.”

“Sure,” I said, and gave him the info. “Now, look, I really need to get upstairs. My mom’s up there. She’s old, and frail, and she needs me. I—”

“Okay. Fine. Just make sure you go straight up.”

“I will.”

Later, I’d remember sensing an odd emptiness, a telltale stillness the moment I let myself in. But at the time, all I could think about was sharing the news about Milford.

No answer. I checked her bedroom, which was right next to the front door, didn’t see her, and ran down the hallway, calling out for her. The bathroom door was open. She wasn’t in there. Not in the kitchen either.

But she was in the living room, sitting in her rocking chair. Her eyes were closed, as though she had fallen asleep, and loosely clasped to her breast, in hands gone slack, was a photograph.

“Mama?”

There was no answer.

“Mama?”

That night, after they had taken her away, I sank down on the sofa. Unable to think. Unable to cry. All I could think about was how she had died alone. Despite all my efforts, all my promises to be there for her, in the end I had left her to die alone. And I kept seeing her, clasping that picture, an image of her in her rocking chair, smiling, holding two plump cats, Dizzy and Gillespie, one under each arm. I had taken pictures of her and pictures of the cats, but none together.

Finally, I dragged myself to bed. I closed my eyes, but I couldn’t fall asleep. After about an hour, I got up and went down the hall to Mama’s room.

The door was closed. I paused, took a deep breath, then gripped the doorknob and went in. I don’t know what I expected—or what I feared—but whatever it was, it didn’t happen. I didn’t break down. I didn’t shed a tear. I was too wound up for it, and maybe too afraid to let go.

Mama’s pills were there, on her dresser, lined up like little soldiers. All of them, except the sedatives. I checked each bottle, checked them again. Where were they? They should’ve been there. I had just filled her prescription the other day. Everything else was there, but the sleeping pills.

Then I knew. I understood where all those pills had gone.

Mama’s heart hadn’t simply given out. She had decided she was tired of living … and knowing she planned to go, she had sent Dizzy and Gillespie along ahead of her. It was my fault, she’d said, my fault they died. It was crazy, but in a crazy kind of way, it made sense.

That’s when the tears came, when the realization hit. I had failed her so completely, to help her, to restore her hope, to get her out of there. I had failed her utterly.

The death certificate issued by the powers that be simply listed heart failure. It did not mention sleeping pills. Maybe they hadn’t bothered to check. Maybe they had just seen a very old woman and assumed she had died of natural causes.

It was a simple funeral, just the way Mama had said she wanted it. Despite her belief that she was all alone, she still had quite a few friends in the neighborhood. They showed up, many of them as frail as she was. They were all kind and supportive, and I thanked them for the love they’d shown her.

That evening, one of them stopped by. It was Mr. Edgar. He lived two floors up, and although he was in his eighties, he was often out and about. I suspected he was sweet on Mama.

“I just wanted to return this.” He held up one of Mama’s pie plates.

“Oh, thank you, but when did she—”

“The other day. She asked me to go to the store for her. I said I would if she would make me a pie.”

“Really?”

“You mean, you didn’t know? She didn’t make you one? ’Cause I bought enough for two.”

Slowly, I shook my head. The fact that my mother found the energy to make it down to the kitchen and bake two pies surprised me no less than the fact that she had asked Mr. Reese to buy the ingredients instead of asking me.

I thanked him and started to close the door, but he stopped me.

“Just one more thing,” he said. “Some cops came by to see me. Asked some strange questions.”

“About what?”

He shrugged. “It’s probably nothing for you to worry about. But they might stop by here.”

I thought it strange that he was so vague, but I didn’t push the matter. He turned around to go, but then caught himself and came back.

“I can’t believe I nearly forgot this.” He reached into his jacket pocket and brought out a small bottle. It was Mama’s missing sleeping pills.

“Your mother gave me these the other day. I happened to mention that I wasn’t sleeping well, and she told me to take them. I said I didn’t need all of them, but she insisted.”

I accepted them in a daze and closed the door. Mama’s sleeping pills. She hadn’t committed suicide. She really had died of heart failure. I started down the hall but found myself standing outside Mama’s door instead. I thought about Dizzy and Gillespie, and how much she loved them.

Then I thought of that picture.

I had buried it with her. I wished I hadn’t. Partly because it would’ve been good to have: a reminder of all-too-brief happy days.

And partly because I wondered who had taken it. I knew I hadn’t.

I tried to picture it, study it.

I remembered my surprise at finding it. Surprise because I didn’t know she had it. Because I didn’t even know it existed. And because … well, it was a Polaroid.

Who in the world still uses Polaroids?

The doorbell rang again.

I thought it was Mr. Edgar or another of Mama’s neighbors. Instead, it was two detectives. They held up their badges and introduced themselves as Jacobi and Reiner.

“Yes?”

They asked about Milford, about what kind of relationship I’d had with him.

“None. I barely knew him.”

“You didn’t get along, right?” That was Jacobi. His gaze slid up and down the hallway, then returned to me.

“What’s this all about?”

“Where are your cats?” Reiner asked.

“My cats?” I looked from one to the other. “They’re both dead. Why?”

“You like to cook, to bake?”

That was Jacobi. He made a move to step around me, to walk down the hall. I stepped in front of him.

“Not really, no.”

He brought his eyes back down to me and I planted my feet, refusing to budge. He didn’t like that. He gave Reiner a nod, as if to say that some suspicion had been confirmed.

Reiner asked, “How did your cats die?”

I didn’t answer.

“We heard that you suspected poisoning,” he went on.

“And that you thought Milford did it,” Jacobi added.

Actually, that thought hadn’t occurred to me. Maybe it would have, if I hadn’t been so quick to assume that I’d done it by accident, or if Mama hadn’t indicated that she’d done it by intent.

“Why exactly are you here? It couldn’t possibly be to investigate the death of two cats.”

“Depends,” Jacobi said.

“On what?”

“On whether it was a motive for murder,” Reiner said.

“Murder?”

“Turns out Milford died from strychnine poison.”

“Really?” I said, keeping my voice calm.

“Yeah, really.” Jacobi studied me. “Turns out it was in a sweet potato pie.”

“And you think I baked it?”

“Did you?” Jacobi asked.

“You sure about that?”

“Very.”

“What about your mother?”

“What about her?”

“We heard that she’s famous for her sweet potato pie.”

“Then you must’ve also heard that she died.”

That took the wind out of their sails. A bit.

“When—”

“The same day Milford died. While the paramedics were downstairs trying to save him, my mother was up here, dying.”

“Why didn’t you call for help?” Reiner asked.

“I wasn’t here. I had gone out. When I got back, there was that mess downstairs, that circus about … him. And your cops wouldn’t let me through. By the time I got upstairs, she was gone.”

They didn’t have an answer for that. They asked me if they could look through the place, and I said no. They warned me they’d be back. I didn’t care. They couldn’t pin Milford’s death on me, and they knew it.

I went back to Mama’s room. I had remembered one more detail. One more reason why that photograph bothered me: the date stamp in the lower right-hand corner.

It was for the day Dizzy died.

Who still uses Polaroids?

Photographers. That’s who. They use them for test shots.

Milford. He must’ve been in our apartment.

“It was my fault,” she said, “my fault they died.”

Something inside me twisted in pain. How could I have gotten it so wrong? She hadn’t killed those cats, but she had let the devil in the door. She had wanted to be the good neighbor, so she had given Milford another chance, and he’d used it to poison Dizzy and Gillespie.

In killing them, he’d killed her, too. Losing those cats had pushed her over the edge. Sure, the doctor had said it was heart failure that killed her, but he might as well have written heartbreak.

“I can’t bring them back,” she’d said, “but I will make it right.”

And she had.

She would’ve still been alive if Milford hadn’t killed those cats—and he would have been, too.

Two months later, I got a good job, and four months after that I’d saved enough to move out. The neighborhood was changing. Columbia University was building a new campus nearby, and everyone was saying how the rents were going to rise. All my friends were telling me how lucky I was to have Mama’s apartment, how I shouldn’t give it up. That the landlord would have to fix it up or buy me out. But I couldn’t take being there. I couldn’t stand it.

It took me days to clean the place out, to empty it of forty years of papers. While doing so, I found an old picture that, from the looks of it, dated back to the 1940s. It was of Mama, all done up. She was seated in a garden, nuzzling two small cats. I was surprised. She’d said she always hated cats. I turned the picture over and found a note on the back: Me, with Cab and Calloway. Just before they died in March of ’45. Cab and Calloway?

“This is twice this has happened to me,” she’d said. So, Mama had had cats before, and they had died mysteriously, too.

I felt a new welling of sadness, of loss, bittersweet.

I set that picture aside. I saved it and, that evening, I took it with me to my new place. It got a special spot on my dresser top, right next to a picture of Dizzy and Gillespie, and a picture of Mama and me.

I miss you so much, I thought. But then I took a step back and looked around and it hit me once again. I did miss her, but I sure didn’t miss that old apartment.

I sat down and took it all in. My new place. My new place. My very own, new place. I said those words out loud, repeated them over and over. I had finally done it. I had moved into one of those townhouse apartments on Convent Avenue, and it was all I’d imagined it to be.

I gazed out my window and sighed.

It was good, so very good, to finally live “over there.”

PERSIA WALKER is a diplomat, former journalist, and the author of acclaimed crime fiction. Her three historical mystery novels, all set in 1920s New York, are Harlem Redux, Darkness and the Devil behind Me, and Black Orchid Blues. She is a native New Yorker, speaks several languages, and has lived in South America and Europe.