KATE HAMILTON, A petite woman of about five foot three, who exuded quiet authority like a plutonium rod giving off radiation, held out her hand for the Young Manager to shake and smiled warmly. Her blue-eyed gaze was direct and unwavering.

“Gary texted ahead,” she said brightly. “It sounds as though you’ve had a busy morning. I imagine your head’s spinning somewhat, is it?”

“Right on both counts,” the Young Manager admitted, grinning.

“Well, don’t worry,” said Kate. “It will all fit together and make sense soon enough.” She led him briskly down the corridor, talking as they went. “Adopting a different way of looking at challenging situations takes time, but once you’ve got your head around it, the process becomes intuitive.”

At the end of the corridor, Kate pushed open a set of double doors and led the Young Manager into a large, busy, open plan office. It was a colourful, space, designed to encourage a playful attitude. Primary coloured freestanding meeting pods dotted the room and one corner was given over to leather bean bags, games consoles and a well-used office ping-pong table. Some worked from standing desks, while others chatted and shared notes as they lounged on sofas with their tablets and laptops. One or two people had treadmills attached to their desks so they could walk while they worked.

“We let the staff design their own workstations. It does wonders for productivity.” said Kate, noticing the Young Manager’s wide eyes. “Jelly bean?” she asked, as they passed a spherical glass candy dispenser on a bright red metal stand.

“I’m fine, thanks,” said the Young Manager, holding up a palm.

Kate ushered him into one of the meeting pods and pulled the frosted screen across the entrance to muffle the sound of her busy team. A trestle table ran up the middle of the space with picnic benches arranged on either side. Kate gestured to one of the benches. “Make yourself comfortable,” she said, glancing at her watch. “I’ve got a new copy-writer turning up in an hour, but we should be done well before then.”

“Thanks,” said the Young Manager, “for your time, I mean.”

Kate nodded as she slid onto the opposite bench. She arranged a small pile of papers in front of herself then, without further ado, she launched into a conversation that seemed like a polished presentation after Gary’s relaxed chat.

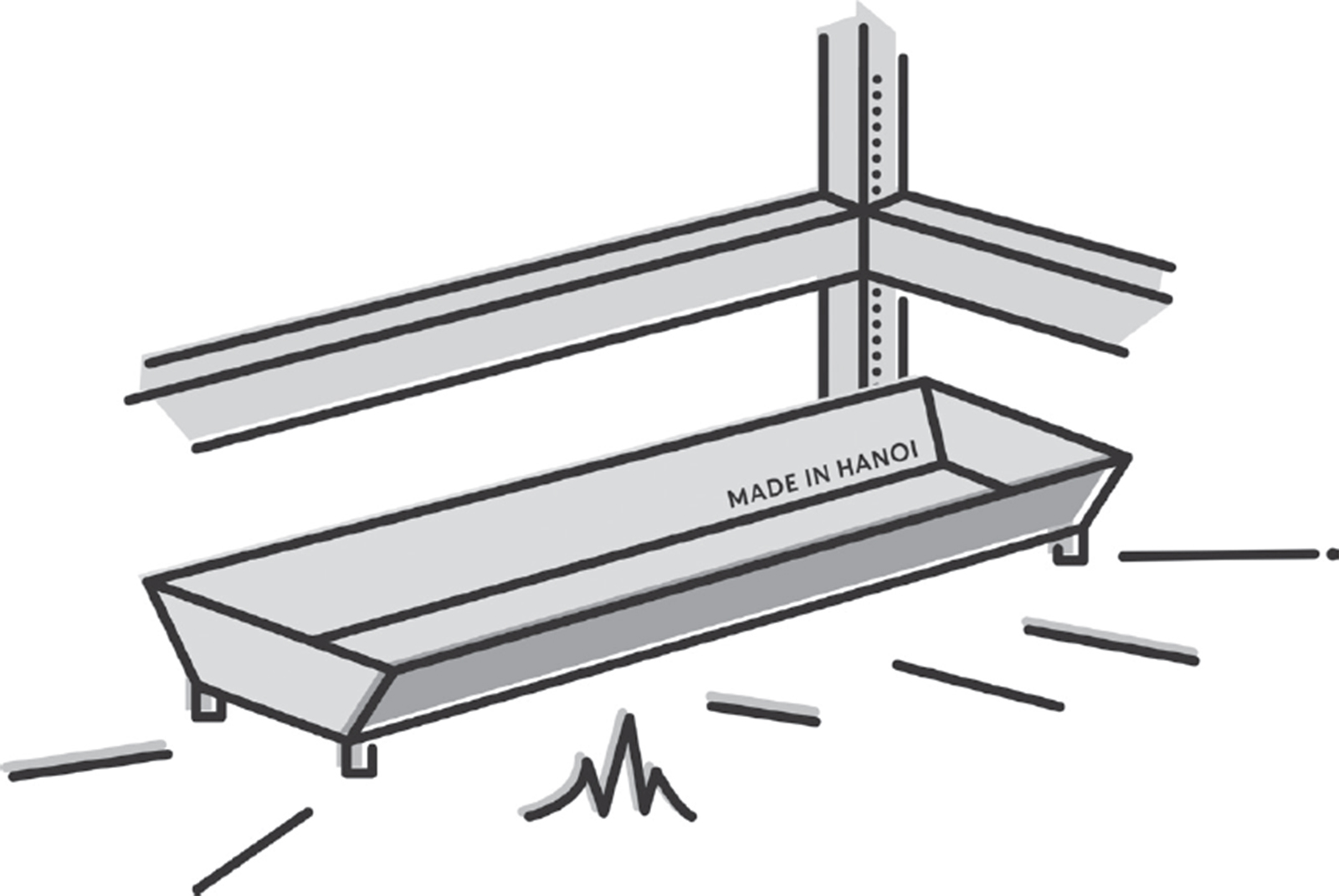

“I’m going to dive straight in with how the Feeding Trough can create breakthroughs in your thinking, as well as how it can help you to spot the assumptions that are holding you back. So, what’s in the trough, eh? What have you been feeding this problem pig of yours?”

“Rage and frustration mostly.” said the Young Manager.

“I can imagine.” Kate smiled. “Okay. First stop, French Hanoi, 1902. The city’s colonial authorities had a pig of their own to wrestle…”

The Young Manager fired up his tablet and began a new section of notes.

“Hanoi was infested with rats.” Kate continued, without pausing for breath, “We’re talking Pied Piper levels. Biblical plague levels. And nothing the city’s bosses tried was having an impact. They couldn’t recruit enough rat catchers. They were completely overrun. So, in desperation, they switched strategy. Instead of hiring yet more pest control workers, the colonial government decided to offer a cash bounty for every rat pelt handed in by any member of the public. The policy was announced publicly and received favourably, with many people expecting a quick end to the city’s rat problem. But that’s not how things worked out.” Shaking her head, she said, “In fact, far from clearing out the rats, things soon took a dramatic turn for the worse. The number of rats in Hanoi went through the roof!”

“I don’t get it,” said the Young Manager, puzzled. “How come?”

“I thought you might figure it out”—Kate winked, miming a wad of banknotes—“because the enterprising population of Hanoi started breeding rats.”

The Young Manager burst out laughing. “Of course they did!” he said, feeling foolish for having missed the obvious scam. He let his laughter subside before adding “Forgive me, though. I don’t see how your story helps me.”

Kate raised an eyebrow and fixed him with her steel gaze. “Think about it,” she said. “The solution that the authorities came up with tells us a lot about how they framed their problem. Based on their strategy, they framed the situation as being one where they needed to increase the number of dead rats.”

“What!?” said the Young Manager. “But wasn’t that the problem they were trying to tackle?”

“Not quite,” Kate replied. “Whilst that might seem to make sense, it is the wrong frame. A better frame would have been to decrease the number of living rats. That is a very different problem.” Kate tapped a finger on the table and said, “So you see, when you have the wrong frame around a problem…”

Our misguided attempts at resolving problems can often fuel the real problem.

“So, if choosing the wrong frame can have such a disastrous impact,” the Young Manager asked, “how do I find the right one?”

“I’m glad you asked,” said Kate, “because I’ve been playing with the photocopier.” She pushed a pile of paper over to the Young Manager’s side of the table, keeping a single sheet back for herself. “How about a little practical experiment?” she asked him.

The Young Manager leafed through the top few pages of the pile, noting the same pattern of nine dots arranged in a three-by-three square, printed on each page.

Kate handed the Young Manager a marker pen. “I want you to connect these nine dots, using four straight lines, but without taking your pen off the page.”

“No problem!” declared the Young Manager, confidently. He’d seen this puzzle somewhere before—on a training course, perhaps, or at a conference. As he placed the pen firmly on the top left dot, though, he faltered, and with a sinking feeling, he realised that he couldn’t actually remember the answer.

“Have as many goes as you like,” said Kate, mischievously, indicating the sizeable stack of copies that she had provided.

“I’ll get it,” said the Young Manager, screwing up his second attempt and reaching for a third sheet. “I just need to remember the trick. Damn!” He scribbled over his latest attempt and frowned.

For all his best efforts, the Young Manager couldn’t crack Kate’s problem. He could feel the pressure was mounting with each failed attempt. The meeting pod was slowly filling up with crumpled sheets, as the stack of fresh ones shrunk smaller and smaller. It was positively embarrassing!

“I think you’ve suffered enough,” said Kate, after a while. “Shall we take a look at the solution together?”

The Young Manager blew the air from his cheeks and set down his pen with relief. “I think we better had,” he said, grinning sheepishly.

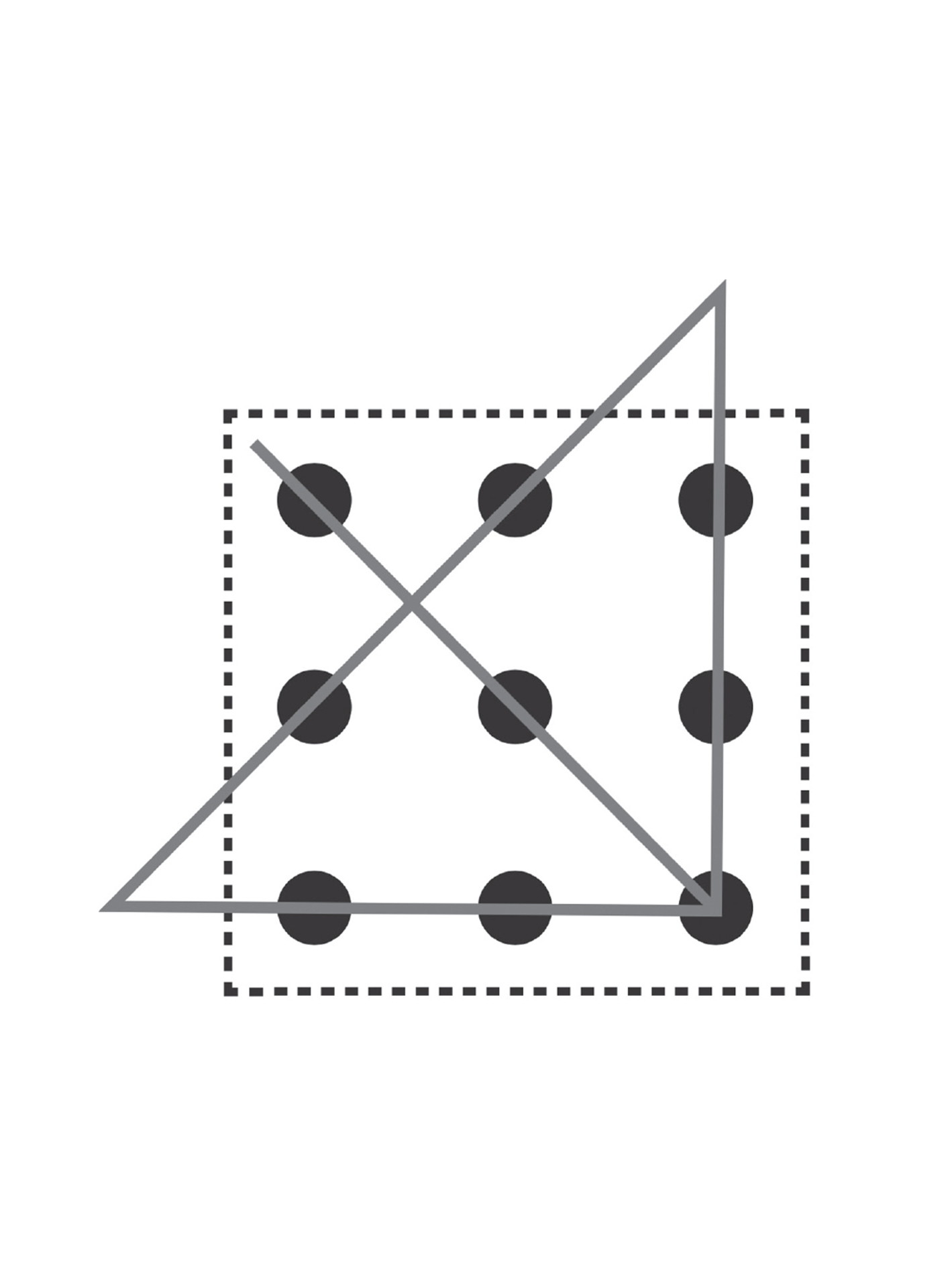

Kate turned over the single sheet that she had reserved, to reveal the puzzle’s answer.

“Of course!” exclaimed the Young Manager, slapping his forehead melodramatically. “You’ve got to think outside the box, as we’ve all heard a million times. Look beyond the grid of dots and go beyond the lines they form.”

“Actually, that’s not quite right,” said Kate. “What we’re saying is that if you hold that assumption, you make it an unsolvable problem. Once you realise that you’re making those assumptions, the potential solutions become endless,” said Kate. “Do you see how you effectively penned in your own thinking with that single assumption you made about the rules of the game?”

“I do now,” said the Young Manager ruefully, “but when you’re stuck in the rut, it’s not so easy.”

“That’s normal,” Kate replied. “But by exploring what hasn’t worked, we can sometimes find the key to unlocking a problematic situation.”

“If it doesn’t work, try something else,” added the Young Manager.

“Exactly,” Kate answered, “but try to remember that it is possible to convince yourself that you are trying all kinds of new angles, when in reality, you may be locked into variations of the same failed approach.”

“Okay, I get that, but how does it relate to the people problems I’ve been facing?” asked the Young Manager.

“Let me give you an example,” Kate began. “Whenever we ask someone with a problem what they’ve already tried, their answer is always roughly the same.”

“It is?” asked the Young Manager, incredulously. “Enlighten me.”

“Well, they always say that they’ve tried everything,” Kate replied, “but that’s rarely the whole truth of the matter.”

“I’ve said it myself, a thousand times!” the Young Manager admitted. “But it was always said with sincerity. Only when I really had exhausted my options.”

Kate looked doubtful. “Well I’m sure you felt like you had tried everything,” she said, “just like you felt like you’d tried everything with those nine dots. That is, until you realised that there was a whole other world of options available to you if you didn’t make the assumption and stick within the imaginary lines. But”—she held up a finger, emphatically—“what’s really fascinating is that in these failed attempts lies the key to real progress. Because, while we may legitimately feel like we have tried everything, we’re often only working within a small sub-set of potential solutions.”

“But how do these failed attempts point to the right solution?” asked the Young Manager, glancing at the pile of crumpled puzzle sheets. “Even if you’d pointed out straight away that I was making an assumption that was preventing me from seeing the solution, I’m not sure I’d have been able to identify that assumption myself.”

“Fair enough,” said Kate. “It’s not always easy to spot where you’re going wrong. But, let’s take another look at some of your failed attempts,” she suggested. “Lay them out on the table in front of you so we can see them all together. Go on…”

Kate pointed at the crumpled papers that littered the pod. The Young Manager raised his eyebrows in query, and she nodded. He took one of the screwed up sheets and carefully opened it out, flattening it out on the table. Then he did the same for another, and another, laying them all out together, so that they covered the table.

“So,” said Kate, when there was no room left for any more puzzle sheets, “do you see what they all have in common?”

“Like we said,” the Young Manager replied, “the obvious thing is that I stayed within an imaginary box with every attempt. I assumed that not going beyond the grid was part of the rules of the game, but in truth, nobody ever told me that.”

“That’s right,” Kate said and nodded. “That’s the assumption that held your thinking captive. And until you spotted that, you were going to be stuck feeling as though you’d tried everything.”

“True,” agreed the Young Manager.

“And in a sense you had,” Kate agreed. “But only everything within that narrow frame you’d given yourself. Now that the full picture is laid out before you, it’s obvious”—she indicated the table covered in failed puzzles—“Your mind is open now. But tell me, what else do your attempts have in common?”

“Hmm,” said the Young Manager, thinking hard, “I used the same pen for all of them, I suppose…”

“Yes, you did,” Kate replied. “But who said you had to stick to the pen I gave you? In theory, you could have found a pen with a nib thick enough to connect the dots with a single pen stroke.”

“I could have thought about folding the paper too, maybe,” said the Young Manager. “Look at me,” he added self-effacingly. “I’m on a roll now.”

“Good thinking,” said Kate. “Do you see how getting an overview of our failed attempts, can help identify the assumptions that are holding us back, and open our minds to new solutions? In essence…”

The themes that connect our failed attempts to resolve a problem highlight the assumptions we are making.

“Those assumptions might be driven by personal experience or misapplied knowledge,” Kate suggested, “or by entrenched cultural notions concerning how we should go about creating change.”

“Like the strategies for dealing with difficult people that my colleagues suggested, you mean?” asked the Young Manager. “All of which were about educating or motivating the staff in one way or another.” He rolled his eyes. “As if we haven’t been there before!”

“Exactly like that,” said Kate, gathering up the papers again into a neat pile. “Even changing something as simple as the context, or the location of where you attempt your solutions can help. So many solutions to people problems are only ever attempted in a formal, business environment. You’d be surprised by the number of problems that get resolved when the context changes, am I right?” She indicated the playful open plan space beyond the meeting pod.

“I take your point,” said the Young Manager, thoughtfully. “So are there other ways to identify assumptions and potential solutions?”

“Well, here’s another way to think about your previous attempts that didn’t quite crack the problem,” said Kate. “Consider the times where you tried something that had a positive impact on the problem, but the impact did not last. Now ask yourself two things: What part of those solutions really seemed to work? and What stopped you from doing more of this approach? Run through those questions and you’ll soon have a new frame to try out.

“Alternatively,” she went on, “you could look at those attempted solutions that made the problem measurably worse, and consider what performing the opposite of those actions might entail. Just like the people of Hanoi, to bring things back to my earlier story.”

“I’d never thought that my failed attempts contained so much useful information,” said the Young Manager. “When I try something that totally bombs, I tend to tick it off the list, sweep it under the carpet and forget all about it.”

“And it’s precisely that tendency that holds you back from resolving challenging problems,” Kate said, decisively. “Maintain your critical eye. Look at unsuccessful solutions. Engage with your failures to open up new ways of thinking, and find new frames to look through.”

A sudden knock on the pod’s frosted door made them both jump. The glass slid open to reveal a stout little man in his forties, with an anxious look on his round face. He had a shiny bald head and a thick bushy moustache. An equally stout French Bulldog wearing a diamante collar stood at his feet staring up at him adoringly, and panting noisily. Kate beckoned him in, and man and dog made their way inside to stand at the foot of the rough wooden table.

“I’m sorry to disturb you,” the man said briskly, “but our guest has arrived rather early, Kate. What do you want me to do with him?”

Kate glanced at her watch. “Sort him out with something to drink and a biscuit, will you, Julian? I’ll be over soon.”

The man nodded, reversed out of the pod, and bustled off across the office, with his dog at his heels.

“Actually,” said Kate, watching her employee leave, “Julian is a pretty good case study for what I was just talking about.”

“How so?” asked the Young Manager.

“A year ago, his performance had slipped to the point where I was genuinely thinking about letting him go.” Kate pulled a face and sighed, heavily. “I didn’t want it to come to that, of course. Julian’s been with me for years, and he’s enormously talented. A real asset when he’s on form. It was the pig wrestling method that helped me to see his fall in performance through a different frame. And when I did that, I learnt something. I found out that the problem wasn’t with Julian at all; it was with Doris.”

“Doris?” asked the Young Manager.

“Doris the bulldog,” said Kate, laughing. “To cut a long story short, Julian started coming into the office late and sneaking off early at the end of the day. He was distracted and unfocused and stopped meeting deadlines.” She frowned. “I had to do something to shake things up, so I scheduled early morning briefings, to force him to come in on time.”

“Did that work at all?” asked the Young Manager.

“Total disaster!” said Kate. “He got here on time, but was more distracted than ever and then nipped off even earlier at the end of the day. A real rats of Hanoi moment.”

“So what did you do?”

“Played hardball,” Kate replied. “I scheduled our team meetings for the end of the day, so he couldn’t wriggle out of his designated office hours.” She rolled her eyes. “That was a mistake. Julian started getting very stressed and snappy with everyone. The whole thing became unbearable for us all. It wasn’t until I looked at all the things I had tried that I realised where I’d gone wrong. Everything had been about trying to keep Julian at work and away from home. Working from home simply isn’t an option in his role, so I had to consider something else entirely. I wondered if rather than keeping him away from whatever was requiring so much attention at home, maybe we should do the opposite and bring that thing into work.” She smiled. “It turned out the thing was Doris. Julian had assumed that there was no way we could have a bulldog around the place, so he never asked.”

“What was up with Doris?” asked the Young Manager.

“She’d started pining badly for Julian while they were apart. It was affecting her health, not to mention his soft furnishings. And it was distracting him from his work on a daily basis. So now Doris comes to work with him, and Julian is firing on all cylinders again. It was as simple as that. Having an office dog around the place has done wonders for other people’s stress levels too. And our clients love her. It all worked out rather well.”

“I wouldn’t mind an office dog myself,” said the Young Manager wistfully. He sat forward on his bench, making as if to rise. “I’m sure I shouldn’t take up any more of your time. I don’t want you to keep anyone waiting on my account,” he said.

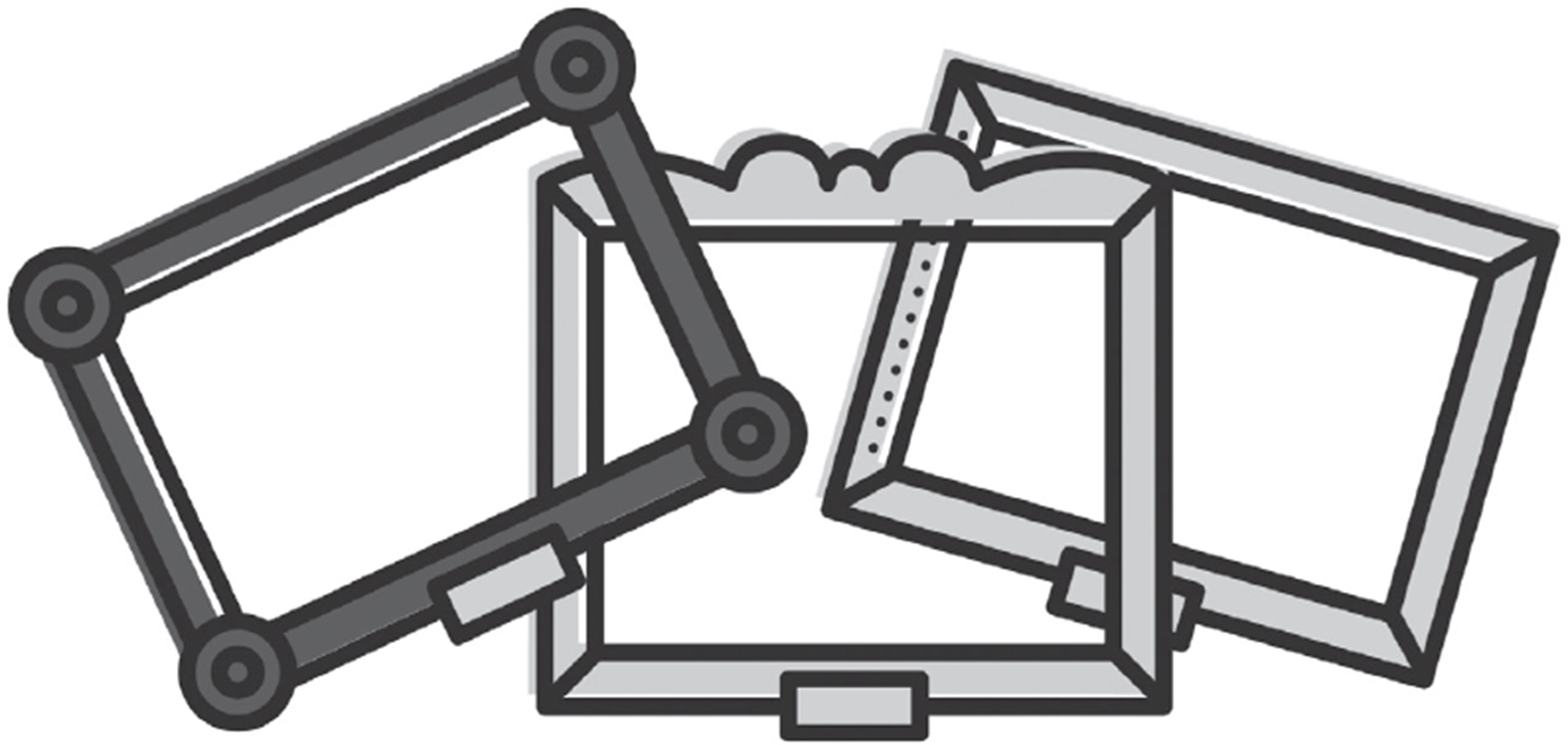

“Don’t worry,” said Kate, stopping him from getting up with a wave of her hand. “I’ve got exactly enough time to show you the next element of the pig-pen mnemonic. And you don’t want to miss this part. It’s my favourite way to step outside of those assumptions that you’re making.”

“The problem with problems in general,” Kate said, continuing her tutorial, “is that we spend far too much time and effort trying to figure out what we should do to solve them.”

The Young Manager looked puzzled. “And, trying to solve problems is a problem?”

“It can be,” said Kate, “because most people spend too much time thinking about how to solve the problem, and not enough time on figuring out how they’d know if the problem were solved. To get around that, the pig-pen crowd use something called the Miracle Question .”

“Well, it’ll take a miracle to resolve my work problems, so fire away,” said the Young Manager, drily.

“The Miracle Question,” said Kate, ignoring his joke, “is an exercise that focuses on ensuring that we know exactly what we’re trying to achieve when we set out to effect change.”

“Shouldn’t that be obvious?” asked the Young Manager.

“You’d be surprised,” said Kate. “The Miracle Question allows you to explore the outcome you genuinely need, not what you think you need, by looking past obstacles and focusing on possibilities for the future.”

“Possibilities for the future…” repeated the Young Manager, making a note on his tablet.

Kate nodded. She pressed her fingertips together and leaned across the table. “The questions that we ask define our reality. They can help us to live our best life, or they can derail us completely. The genius behind the Miracle Question is that it forces you to stop thinking about how you might solve a problem, and instead focus on how you’d know it was solved. Picture perfection, then work back from there, to identify what you really need happen.”

“That actually sounds pretty simple,” said the Young Manager. “I’m great with what ifs.”

“It might sound simple, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy,” said Kate. “Most people can rattle off the problems in their life easily enough, but they often struggle when it comes to answering the Miracle Question. The miracle question isn’t about finding solutions, it’s about how you’d know the solution had been found and implemented successfully. It bypasses the need to find a solution and so helps people avoid getting stuck in searching for the solution. The crucial point is that you have to…”

Stop thinking about how you are going to solve this problem, and start thinking how you’ll know it is solved.

“Fine,” said the Young Manager, “tell me how to do that, then.”

Kate reached into her pocket for a piece of neatly folded paper. She unfolded it to reveal a printed picture of the crystal ball from the pig-pen scene, and pushed it across the table to the Young Manager.

“I didn’t have a real one to hand, I’m afraid,” she joked. “So we’ll have to make do with my photocopying skills again. Take a moment to…”

Imagine that you could look into this crystal ball, to a time after a miracle had happened. What would you see once this problem was solved?

“Now, examine that picture closely. Filter out the nice-to-haves, and identify the need-to-haves. The things that will need to have changed to accomplish your vision. Go on. Give me a couple of examples.”

The Young Manager thought for a few moments. “Okay,” he said finally, “so if there’s been a miracle…the teams that I manage have stopped disagreeing and started getting along with each other. Oh, and the challenging people in those teams have got into the habit of automatically updating the monthly spreadsheet with their data, without constantly needing to be nagged.”

“Well,” said Kate, “that’s an interesting place to start. In the first place, both of those descriptions are crammed full of dirty language and generalisations. And secondly they both sound like solutions pretending to be problems.”

The Young Manager was annoyed with himself. He’d made exactly the error that Gary had warned him about. “Busted,” he said sheepishly. “I should have been thinking about facts and behaviours rather than generalising. But what do you mean by solutions pretending to be problems?”

“Let’s look at the second part of the miracle you painted,” Kate continued. “I’m guessing that what you actually need is a regular and reliable source of numbers from your people, so you can collate them into a single file. I’m guessing your monthly spreadsheet is the current means of gathering that data, right?”

“Right,” said the Young Manager, still unsure of the point Kate was making.

Kate smiled. “That monthly spreadsheet of yours isn’t one of your problems at all. It’s a failed solution to the problem of data gathering. There are many other ways to collate that data without using a group spreadsheet and touring the office to nag your staff. At the end of the day, all you need are the figures. Try a phone call, or a regular round of coffees with a data catch-up. Maybe you could solve the problem simply by delegating that data gathering to a junior member of the team, for whom it would be higher up their own list of priorities. It depends on what you are trying to achieve. Just make sure you stay focussed on the need-to-haves, not the nice-to-haves. Sure, it would be lovely if every one of your employees were conscientious and proactive in updating spreadsheets. But they’re not. The notion that you can encourage them towards perfection in this regard is a Utopian fallacy, a road that leads to lifelong pig wrestling and frustration.”

“I think I know what you mean,” the Young Manager replied, slightly defensively. “But is it really too much to ask that the staff just email their results to me? Isn’t it disrespectful of them to ignore my request?”

“Oh, I see,” said Kate, with a sideways smile. “So the problem isn’t the numbers. It’s that you don’t feel you’re getting the respect you deserve.”

“Well, no, not really…I mean, it is the numbers”—the Young Manager blushed—“only it would be nice if—”

“I’m going to stop you there,” Kate cut in. “It would be nice if your staff showed unswerving respect for your authority, and it would be nice if they did everything you ever asked without question or carelessness. But that’s not a particularly realistic expectation, is it?”

“I guess not,” the Young Manager agreed.

“See?” said Kate. “Those nice-to-haves have lead you straight into a muddy pig pen and left you stuck there. The labels you’re attaching to the people in your team are penning in your thinking. They’re being disrespectful and unreliable. Moreover, getting hung up on the nice-to-haves is holding you back from seeing what the need-to-haves actually are.”

“To be honest,” the Young Manager reflected and said, “I can think of dozens of times when I’ve tried something that I pretty much knew wouldn’t address the underlying issue, just to feel like I was doing something.”

“Taking action for the sake of appearances,” said Kate, “that’s not uncommon. But fluffing around with the nonessentials while failing to address the fundamentals is a bit like putting lipstick on a pig isn’t it?”

They both chuckled at the mental image.

“Switch your thinking,” Kate continued, “and you’ll be able to step outside of your assumptions to see the full range of solutions that are available to you.”

The Young Manager scrolled through his notes. “Okay,” he said, “let’s summarise the Tin Feeding Trough, and the Crystal Ball…”

“Not a bad summary,” said Kate. “You’ve got the key point, which is to stop solutioneering for a moment, and look at what you’ve already tried. Spot the assumptions you’re making and identify what you really need to happen instead. Both of those strategies will help you to spot the old frame that you’ve put around the problem, and identify a new frame that fits better.”

“Thanks Kate,” the Young Manager said. “I feel like I might be making real progress. You know, I think I maybe understand enough of this process to get cracking!”

“You’re welcome, but take care,” Kate warned. “Having learnt the first few elements, it can be tempting to think that you know enough to begin taking action. But that would be a mistake. What you’ll learn next will ensure that you don’t waste your own and everyone else’s time. It will allow you to create the change you need, in an efficient and impactful way.”

“Understood,” the Young Manager replied, somewhat apologetically. “I guess I’m getting ahead of myself.”

“That’s only natural,” Kate replied with a smile. “Now, speaking of being efficient, I’m going to have to cut things short, but we should meet for coffee and a chat soon.”

“Definitely,” said the Young Manager, grinning broadly, as he reached out to shake her hand, “I know just the place.”

“Best espresso in the city,” Kate said with a wink. “Now, two more stops and you can get on with your life,” she added, leading them out of the meeting room. “David’s next. He’ll take you through the next three elements of the Pig Pen. He’s a sport’s coach by profession. Head down to the basement. They’ve got the whole level. I’ll let him know you’re on your way.”

“In more ways than one, I hope,” said the Young Manager.

“No doubt,” said Kate encouragingly, before nodding a final farewell and walking briskly away.

The Young Manager left Kate’s colourful top floor office and headed down to the basement. He took the stairs to give himself time to think about his troubles again. Now he knew that his assumptions had kept him trapped inside the pig pen, just like Kate had said. How often had he been guilty of trying variations on the same failed solution? He’d certainly never thought to look at what might connect all of those failed attempts. And what of his people problem? It seemed he had been looking through the wrong frame all along?

His mind wandered to thoughts of the firm’s new IT system. It was intended to enhance collaboration, and so much time and money had been invested in its design and roll-out. Was that just a solution pretending to be a problem as Kate had suggested? Now he wondered why, by comparison, so little time had been spent identifying how the leadership team would know whether their staff were collaborating better. The sloppily designed collaborative practices might actually be feeding some of the problems they were aimed at resolving! The Young Manager’s mind was filling with new questions—What did they specifically need to happen? How much collaboration was enough? Surely expecting everyone to collaborate on everything was one of those utopian fallacies, wasn’t it? What were the nice-to-haves and the need-to-haves?

The Young Manager resolved to explore this in depth with the team when he got back to the office. The current solution was certainly throwing up more problems that it was solving.