ON MARCH 103, 1876, seven famous words sent an even greater avalanche of wires cascading down over an already tangled world: “Mr. Watson, come here, I want you.”

As though living in a desert that was waiting to be planted and watered, millions of people heard and heeded the call. For although in 1879 only 250 people owned telephones in all of New York City, just ten years later, from that same soil, fertilized by an idea, dense forests of telephone poles were sprouting eighty and ninety feet tall, bearing up to thirty cross-branches each. Each tree in these electric groves supported up to three hundred wires, obscuring the sun and darkening the avenues below.

The Blizzard of 1888, New York City Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York

Calvert and German Streets, Baltimore, Maryland, circa 1889. From E. B. Meyer, Underground Transmission and Distribution, McGraw-Hill, N.Y., 1916

The electric light industry was conceived at roughly the same time. One hundred and twenty-six years after a few Dutch pioneers taught their eager pupils how to store a small quantity of electric fluid in a glass jar, the Belgian Zénobe Gramme gave to the descendants of those pioneers the knowledge, so to speak, of how to remove that jar’s lid. His invention of the modern dynamo made possible the generation of virtually unlimited quantities of electricity. By 1875, dazzling carbon arc lamps were lighting outdoor public spaces in Paris and Berlin. By 1883, wires carrying two thousand volts were trailing across residential rooftops in the West End of London. Meanwhile, Thomas Edison had invented a smaller and gentler lamp, the modern incandescent, that was more suitable for bedrooms and kitchens, and in 1881 on Pearl Street in New York City he built the first of hundreds of central stations supplying direct current (DC) electric power to outlying customers. Thick wires from these stations soon joined their thinner comrades, strung between high branches of the spreading electric groves shading streets in cities across America.

And then another species of invention was planted alongside: alternating current (AC). Although many, including Edison, wanted to eradicate the invader, to pull it out by the roots as being too dangerous, their warnings were to no avail. By 1885, the Hungarian trio of Károly Zipernowsky, Otis Bláthy, and Max Déri had designed a complete AC generation and distribution system and began installing these in Europe.

In the United States, George Westinghouse adopted the AC system in the spring of 1887 and the “battle of the currents” escalated, Westinghouse vying with Edison for the future of our world. In one of the last salvos of that brief war, on page 16 of its January 12, 1889 issue, Scientific American published the following challenge:

The direct and alternating current advocates are engaged in active attack upon each other on the basis of the relative harmfulness of the two systems. One engineer has suggested a species of electric duel to settle the matter. He proposes that he shall receive the direct current while his opponent shall receive the alternating current. Both are to receive it at the same voltage, and it is to be gradually increased until one succumbs, and voluntarily relinquishes the contest.

The State of New York settled the matter by adopting the electric chair as its new means of executing murderers. Yet, although alternating current was the more dangerous, it won the duel which was even then playing out not between individual combatants, but between commercial interests. Long-distance suppliers of electricity had to find economical ways to deliver ten thousand times more power through the average wire than had previously been necessary. Using the technology available at that time, direct current systems could not compete.

From these beginnings electrical technology, having been carefully sowed, fertilized, watered, and nurtured, shot skyward and outward toward and beyond every horizon. It was Nikola Tesla’s invention of the polyphase AC motor, patented in 1888, enabling industries to use alternating current not just for lighting but for power, that provided the last necessary ingredient. In 1889, quite suddenly, the world was being electrified on a scale that could scarcely have been conceived when Dr. George Beard first described a disease called neurasthenia. The telegraph had “annihilated space and time,” many had said at the time. But twenty years later the electric motor made the telegraph look like a child’s toy, and the electric locomotive was poised to explode onto the countryside.

In early 1888, just thirteen electric railways had operated in the United States on a total of forty-eight miles of track, and a similar number in all of Europe. So spectacular was the growth of this industry that by the end of 1889, roughly a thousand miles of track had been electrified in the United States alone. In another year that number again tripled.

Eighteen eighty-nine is the year manmade electrical disturbances of the earth’s atmosphere took on a global, rather than local, character. In that year the Edison General Electric Company was incorporated, and the Westinghouse Electric Company was reorganized as the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company. In that year Westinghouse acquired Tesla’s alternating current patents and put them to use in its generating stations, which grew to 150 in number in 1889, and to 301 in 1890. In the United Kingdom, amendment of the Electric Lighting Act in 1888 eased regulations on the electric power industry and made central power station development commercially feasible for the first time. And in 1889, the Society of Telegraph Engineers and Electricians changed its name to the now more appropriate Institution of Electrical Engineers. In 1889, sixty-one producers in ten countries were manufacturing incandescent lamps, and American and European companies were installing plants in Central and South America. In that year Scientific American reported that “so far as we know, every city in the United States is provided with arc and incandescent illumination, and the introduction of electric lighting is rapidly extending to the smaller towns.”1 Also in that year, Charles Dana, writing in the Medical Record, reported on a new class of injuries, previously produced only by lightning. They were due, he said, to “the extraordinary increase now going on in the practical application of electricity, nearly $100,000,000 being already invested in lights and power alone.” In 1889, most historians agree, the modern electrical era opened.

And in 1889, as if the heavens had suddenly opened as well, doctors in the Americas, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia were overwhelmed by a flood of critically ill patients suffering from a strange disease that seemed to have come like a thunderbolt from nowhere, a disease that many of these doctors had never seen before. That disease was influenza, and that pandemic lasted four continuous years and killed at least one million people.

Influenza Is an Electrical Disease

Suddenly and inexplicably, influenza, whose descriptions had remained consistent for thousands of years, changed its character in 1889. Flu had last seized most of England in November 1847, over half a century earlier. The last flu epidemic in the United States had raged in the winter of 1874–1875. Since ancient times, influenza had been known as a capricious, unpredictable disease, a wild animal that came from nowhere, terrorized whole populations at once without warning and without a schedule, and disappeared as suddenly and mysteriously as it had arrived, not to be seen again for years or decades. It behaved unlike any other illness, was thought not to be contagious, and received its name because its comings and goings were said to be governed by the “influence” of the stars.

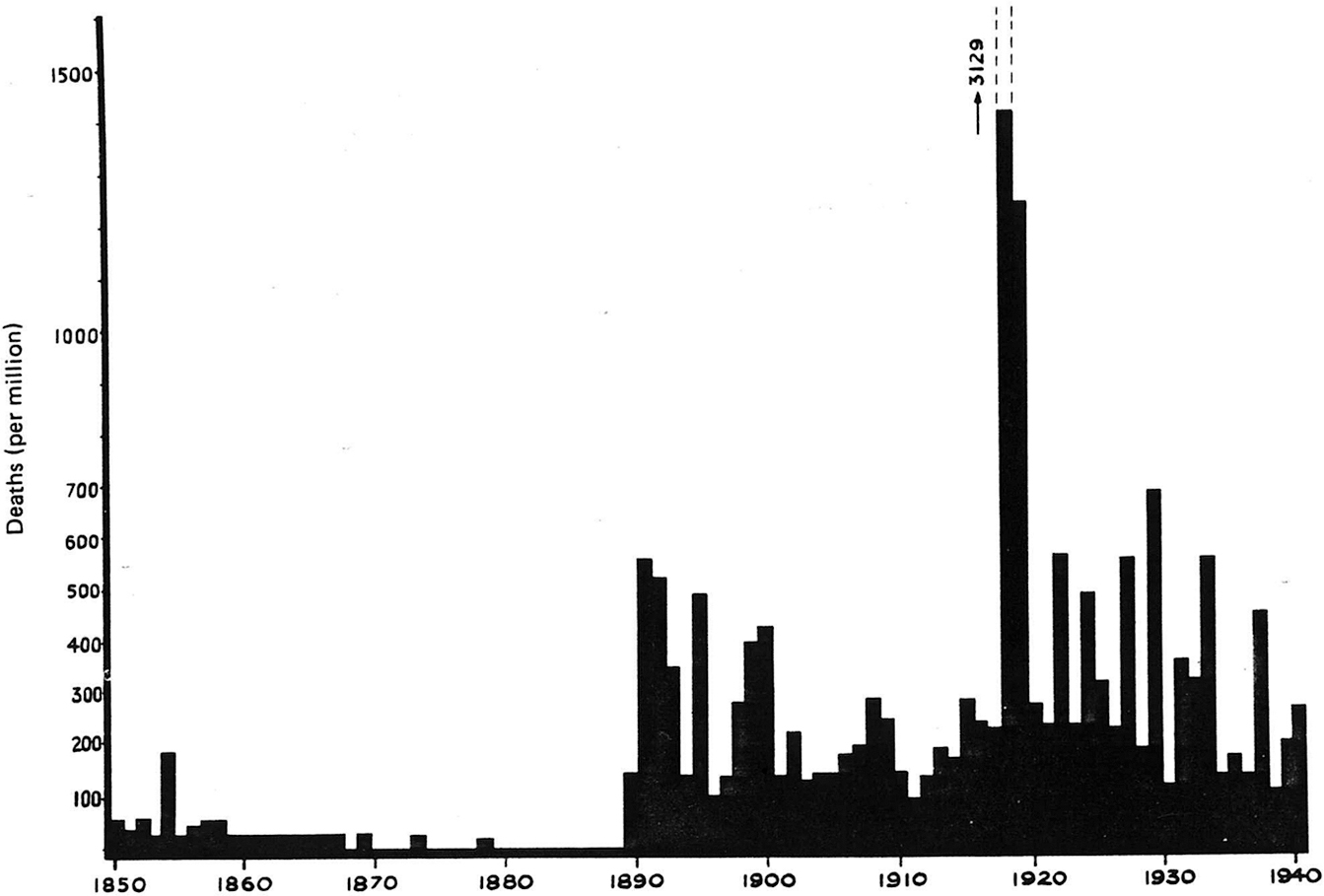

Influenzal deaths per million in England and Wales, 1850-19402

But in 1889 influenza was tamed. From that year forward it would be present always, in every part of the world. It would vanish mysteriously as before, but it could be counted on to return, at more or less the same time, the following year. And it has never been absent since.

Like “anxiety disorder,” influenza is so common and so seemingly familiar that a thorough review of its history is necessary to unmask this stranger and convey the enormity of the public health disaster that occurred one hundred and thirty years ago. It’s not that we don’t know enough about the influenza virus. We know more than enough. The microscopic virus associated with this disease has been so exhaustively studied that scientists know more about its tiny life cycle than about any other single microorganism. But this has been a reason to ignore many unusual facts about this disease, including the fact that it is not contagious.

In 2001, Canadian astronomer Ken Tapping, together with two British Columbia physicians, were the latest scientists to confirm, yet again, that for at least the last three centuries influenza pandemics have been most likely to occur during peaks of solar magnetic activity—that is, at the height of each eleven-year sun cycle.

Such a trend is not the only aspect of this disease that has long puzzled virologists. In 1992, one of the world’s authorities on the epidemiology of influenza, R. Edgar Hope-Simpson, published a book in which he reviewed the essential known facts and pointed out that they did not support a mode of transmission by direct human-to-human contact. Hope-Simpson had been perplexed by influenza for a long time, in fact ever since he had treated its victims as a young general practitioner in Dorset, England, during the 1932–1933 epidemic—the very epidemic during which the virus that is associated with the disease in humans was first isolated. But during his 71-year career Hope-Simpson’s questions were never answered. “The sudden explosion of information about the nature of the virus and its antigenic reactions in the human host,” he wrote in 1992, had only “added to the features calling for explanation.”3

Why is influenza seasonal? he still wondered. Why is influenza almost completely absent except during the few weeks or months of an epidemic? Why do flu epidemics end? Why don’t out-of-season epidemics spread? How do epidemics explode over whole countries at once, and disappear just as miraculously, as if suddenly prohibited? He could not figure out how a virus could possibly behave like this. Why does flu so often target young adults and spare infants and the elderly? How is it possible that flu epidemics traveled at the same blinding speed in past centuries as they do today? How does the virus accomplish its so-called “vanishing trick”? This refers to the fact that when a new strain of the virus appears, the old strain, between one season and the next, has vanished completely, all over the world at once. Hope-Simpson listed twenty-one separate facts about influenza that puzzled him and that seemed to defy explanation if one assumed that it was spread by direct contact.

He finally revived a theory that was first put forward by Richard Shope, the researcher who isolated the first flu virus in pigs in 1931, and who also did not believe that the explosive nature of many outbreaks could be explained by direct contagion. Shope, and later Hope-Simpson, proposed that the flu is not in fact spread from person to person, or pig to pig, in the normal way, but that it instead remains latent in human or swine carriers, who are scattered in large numbers throughout their communities until the virus is reactivated by an environmental trigger of some sort. Hope-Simpson further proposed that the trigger is connected to seasonal variations in solar radiation, and that it may be electromagnetic in nature, as a good many of his predecessors during the previous two centuries had suggested.

When Hope-Simpson was young and beginning his practice in Dorset, a Danish physician named Johannes Mygge, at the end of a long and distinguished career, had just published a monograph in which he too showed that influenza pandemics tended to occur during years of maximum solar activity, and further that the yearly number of cases of flu in Denmark rose and fell with the number of sunspots. In an era in which epidemiology was becoming nothing more than a search for microbes, Mygge admitted, and knew already from hard experience, that “he who dances out of line risks having his feet stomped on.”4 But he was certain that influenza had something to do with electricity, and he had come to this conviction in the same way I did: from personal experience.

In 1904 and 1905, Mygge had kept a careful diary of his health for nine months, and he later compared it to records of the electrical potential of the atmosphere, which he had recorded three times a day for ten years as part of another project. It turned out that his incapacitating migraine-like headaches, which he had always known were connected to changes in the weather, almost always fell on the day of, or one day before, a sudden severe rise or drop in the value of the atmospheric voltage.

But headaches were not the only effects. On the days of such electrical turmoil, almost without exception, his sleep was broken and unrestful and he was bothered with dizziness, irritable mood, a feeling of confusion, buzzing sensations in his head, pressure in his chest, and an irregular heartbeat, and sometimes, he wrote, “my condition had the character of a threatening influenza attack, which in every case was not essentially different from the onset of an actual attack of that illness.”5

Others who have connected influenza with sunspots or atmospheric electricity include John Yeung (2006), Fred Hoyle (1990), J. H. Douglas Webster (1940), Aleksandr Chizhevskiy (1936), C. Conyers Morrell (1936), W. M. Hewetson (1936), Sir William Hamer (1936), Gunnar Edström (1935), Clifford Gill (1928), C. M. Richter (1921), Willy Hellpach (1911), Weir Mitchell (1893), Charles Dana (1890), Louise Fiske Bryson (1890), Ludwig Buzorini (1841), Johann Schönlein (1841), and Noah Webster (1799). In 1836, Heinrich Schweich observed that all physiological processes produce electricity, and proposed that an electrical disturbance of the atmosphere may prevent the body from discharging it. He repeated the then-common belief that the accumulation of electricity within the body causes the symptoms of influenza. No one has yet disproven this.

It is of interest that between 1645 and 1715, a period astronomers call the Maunder Minimum, when the sun was so quiet that virtually no sunspots were to be seen and no auroras graced polar nights—during which, according to native Canadian tradition, “the people were deserted by the lights from the sky,”6 —there were also no worldwide pandemics of flu. In 1715, sunspots reappeared suddenly after a lifetime’s absence. In 1716, the famous English astronomer Sir Edmund Halley, at sixty years of age, published a dramatic description of the northern lights. It was the first time he had ever seen them. But the sun was still not fully active. As though it had woken up after a long sleep, it stretched its legs, yawned, and lay down again after displaying only half the number of sunspots that it shows us today at the peak of each eleven-year solar cycle. It wasn’t until 1727 that the sunspot number surpassed 100 for the first time in over a century. And in 1728 influenza arrived in waves over the surface of the earth, the first flu pandemic in almost a hundred and fifty years. More universal and enduring than any in previously recorded history, that epidemic appeared on every continent, became more violent in 1732, and by some reports lasted until 1738, the peak of the next solar cycle.7 John Huxham, who practiced medicine in Plymouth, England, wrote in 1733 that “scarce any one had escaped it.” He added that there was “a madness among dogs; the horses were seized with the catarrh before mankind; and a gentleman averred to me, that some birds, particularly the sparrows, left the place where he was during the sickness.”8 An observer in Edinburgh reported that some people had fevers for sixty continuous days, and that others, not sick, “died suddenly.”9 By one estimate, some two million people worldwide perished in that pandemic.10

If influenza is primarily an electrical disease, a response to an electrical disturbance of the atmosphere, then it is not contagious in the ordinary sense. The patterns of its epidemics should prove this, and they do. For example, the deadly 1889 pandemic began in a number of widely scattered parts of the world. Severe outbreaks were reported in May of that year simultaneously in Bukhara, Uzbekistan; Greenland; and northern Alberta.11 Flu was reported in July in Philadelphia12 and in Hillston, a remote town in Australia,13 and in August in the Balkans.14 This pattern being at odds with prevailing theories, many historians have pretended that the 1889 pandemic didn’t “really” start until it had seized the western steppes of Siberia at the end of September and that it then spread in an orderly fashion from there outward throughout the rest of the world, person to person by contagion. But the trouble is that the disease still would have had to travel faster than the trains and ships of the time. It reached Moscow and St. Petersburg during the third or fourth week of October, but by then, influenza had already been reported in Durban, South Africa15 and Edinburgh, Scotland.16 New Brunswick, Canada,17 Cairo,18 Paris,19 Berlin,20 and Jamaica21 were reporting epidemics in November; London, Ontario on December 4;22 Stockholm on December 9;23 New York on December 11;24 Rome on December 12;25 Madrid on December 13;26 and Belgrade on December 15.27 Influenza struck explosively and unpredictably, over and over in waves until early 1894. It was as if something fundamental had changed in the atmosphere, as if brush fires were being ignited by some unknown vandal randomly, everywhere in the world.

One observer in East Central Africa, which was struck in September 1890, asserted that influenza had never before appeared in that part of Africa at all, not within the memory of the oldest living inhabitants.28

“Influenza,” said Dr. Benjamin Lee of the Pennsylvania State Board of Health, “spreads like a flood, inundating whole sections in an hour… It is scarcely conceivable that a disease which spreads with such astonishing rapidity, goes through the process of re-development in each person infected, and is only communicated from person to person or by infected articles.”29

Influenza works its caprice not only on land, but at sea. With today’s speed of travel this is no longer obvious, but in previous centuries, when sailors were attacked with influenza weeks, or even months, out of their last port of call, it was something to remember. In 1894, Charles Creighton described fifteen separate historical instances where entire ships or even many ships in a naval fleet were seized by the illness far from landfall, as if they had sailed into an influenzal fog, only to discover, in some cases, upon arriving at their next port, that influenza had broken out on land at the same time. Creighton added one report from the contemporary pandemic: the merchantship “Wellington” had sailed with its small crew from London on December 19, 1891, bound for Lyttelton, New Zealand. On the 26th of March, after over three months at sea, the captain was suddenly shaken by intense febrile illness. Upon arriving at Lyttelton on April 2, “the pilot, coming on board found the captain ill in his berth, and on being told the symptoms at once said, ‘It is the influenza: I have just had it myself.’”30

An 1857 report was so compelling that William Beveridge included it in his 1975 textbook on influenza: “The English warship Arachne was cruising off the coast of Cuba ‘without any contact with land.’ No less than 114 men out of a crew of 149 fell ill with influenza and only later was it learnt that there had been outbreaks in Cuba at the same time.”31

The speed at which influenza travels, and its random and simultaneous pattern of spread, has perplexed scientists for centuries, and has been the most compelling reason for some to continue to suspect atmospheric electricity as the cause, despite the known presence of an extensively studied virus. Here is a sampling of opinion, old and modern:

Perhaps no disease has ever been observed to affect so many people in so short a time, as the Influenza, almost a whole city, town, or neighborhood becoming affected in a few days, indeed much sooner than could be supposed to spread from contagion.

Mercatus relates, that when it prevailed in Spain, in 1557, the greatest part of the people were seized in one day.

Dr. Glass says, when it was rife in Exeter, in 1729, two thousand were attacked in one night.

Shadrach Ricketson, M.D. (1808), A Brief History of the Influenza32

The simple fact is to be recollected that this epidemic affects a whole region in the space of a week; nay, a whole continent as large as North America, together with all the West Indies, in the course of a few weeks, where the inhabitants over such vast extent of country, could not, within so short a lapse of a time, have had the least communication or intercourse whatever. This fact alone is sufficient to put all idea of its being propagated by contagion from one individual to another out of the question.

Alexander Jones, M.D. (1827), Philadelphia Journal of the Medical and Physical Sciences33

Unlike cholera, it outstrips in its course the speed of human intercourse.

Theophilus Thompson, M.D. (1852), Annals of Influenza or Epidemic Catarrhal Fever in Great Britain from 1510 to 183734

Contagion alone is inadequate to explain the sudden outbreak of the disease in widely distant countries at the same time, and the curious way in which it has been known to attack the crews of ships at sea, where communication with infected places or persons was out of the question.

Sir Morell Mackenzie, M.D. (1893), Fortnightly Review35

Usually influenza travels at the same speed as man but at times it apparently breaks out simultaneously in widely separated parts of the globe.

Jorgen Birkeland (1949), Microbiology and Man36

[Before 1918] there are records of two other major epidemics of influenza in North America during the past two centuries. The first of these occurred in 1789, the year in which George Washington was inaugurated President. The first steamboat did not cross the Atlantic until 1819, and the first steam train did not run until 1830. Thus, this outbreak occurred when man’s fastest conveyance was the galloping horse. Despite this fact, the influenza outbreak of 1789 spread with great rapidity; many times faster and many times farther than a horse could gallop.

James Bordley III, M.D. and A. McGehee Harvey, M.D. (1976), Two Centuries of American Medicine, 1776–197637

Flu virus may be communicated from person to person in droplets of moisture from the respiratory tract. However, direct communication cannot account for simultaneous outbreaks of influenza in widely separated places.

Roderick E. McGrew (1985), Encyclopedia of Medical History38

Why have epidemic patterns in Great Britain not altered in four centuries, centuries that have seen great increases in the speed of human transport?

John J. Cannell, M.D. (2008), “On the Epidemiology of Influenza,” in Virology Journal

The role of the virus, which infects only the respiratory tract, has baffled some virologists because influenza is not only, or even mainly, a respiratory disease. Why the headache, the eye pain, the muscle soreness, the prostration, the occasional visual impairment, the reports of encephalitis, myocarditis, and pericarditis? Why the abortions, stillbirths, and birth defects?39

In the first wave of the pandemic of 1889 in England, neurological symptoms were most often prominent and respiratory symptoms absent.40 Most of Medical Officer Röhring’s 239 flu patients at Erlangen, Bavaria, had neurological and cardiovascular symptoms and no respiratory disease. Nearly one-quarter of the 41,500 cases of flu reported in Pennsylvania as of May 1, 1890 were classified as primarily neurological and not respiratory.41 Few of David Brakenridge’s patients in Edinburgh, or Julius Althaus’ patients in London, had respiratory symptoms. Instead they had dizziness, insomnia, indigestion, constipation, vomiting, diarrhea, “utter prostration of mental and bodily strength,” neuralgia, delirium, coma, and convulsions. Upon recovery many were left with neurasthenia, or even paralysis or epilepsy. Anton Schmitz published an article titled “Insanity After Influenza” and concluded that influenza was primarily an epidemic nervous disease. C. H. Hughes called influenza a “toxic neurosis.” Morell Mackenzie agreed:

In my opinion the answer to the riddle of influenza is poisoned nerves… In some cases it seizes on that part of (the nervous system) which governs the machinery of respiration, in others on that which presides over the digestive functions; in others again it seems, as it were, to run up and down the nervous keyboard, jarring the delicate mechanism and stirring up disorder and pain in different parts of the body with what almost seems malicious caprice… As the nourishment of every tissue and organ in the body is under the direct control of the nervous system, it follows that anything which affects the latter has a prejudicial effect on the former; hence it is not surprising that influenza in many cases leaves its mark in damaged structure. Not only the lungs, but the kidneys, the heart, and other internal organs and the nervous matter itself may suffer in this way.42

Insane asylums filled up with patients who had had influenza, people suffering variously from profound depression, mania, paranoia, or hallucinations. “The number of admissions reached unprecedented proportions,” reported Albert Leledy at the Beauregard Lunatic Asylum, at Bourges, in 1891. “Admissions for the year exceed those of any previous year,” reported Thomas Clouston, superintending physician of the Royal Edinburgh Asylum for the Insane, in 1892. “No epidemic of any disease on record has had such mental effects,” he wrote. In 1893, Althaus reviewed scores of articles about psychoses after influenza, and the histories of hundreds of his own and others’ patients who had gone insane after the flu during the previous three years. He was perplexed by the fact that the majority of psychoses after influenza were developing in men and women in the prime of their life, between the ages of 21 and 50, that they were most likely to occur after only mild or slight cases of the disease, and that more than one-third of these people had not yet regained their sanity.

The frequent lack of respiratory illness was also noted in the even deadlier 1918 pandemic. In his 1978 textbook Beveridge, who had lived through it, wrote that half of all influenza patients in that pandemic did not have initial symptoms of nasal discharge, sneezing, or sore throat.43

The age distribution is also wrong for contagion. In other kinds of infectious diseases, like measles and mumps, the more aggressive a strain of virus is and the faster it spreads, the more rapidly adults build up immunity and the younger the population that gets it every year. According to Hope-Simpson, this means that between pandem- ics influenza should be attacking mainly very young children. But influenza keeps on stubbornly targeting adults; the average age is almost always between twenty and forty, whether during a pandemic or not. The year 1889 was no exception: influenza felled preferentially vigorous young adults in the prime of their life, as if it were maliciously choosing the strongest instead of the weakest of our species.

Then there is the confusion about animal infections, which are so much in the news year after year, scaring us all about catching influenza from swine or birds. But the inconvenient fact is that throughout history, for thousands of years, all sorts of animals have caught the flu at the same time as humans. When the army of King Karlmann of Bavaria was seized by influenza in 876 A.D., the same disease also decimated the dogs and the birds.44 In later epidemics, up to and including the twentieth century, illness was commonly reported to break out among dogs, cats, horses, mules, sheep, cows, birds, deer, rabbits, and even fish at the same time as humans.45 Beveridge listed twelve epidemics during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in which horses caught the flu, usually one or two months before the humans. In fact, this association was considered so reliable that in early December 1889, Symes Thompson, observing flu-like illness in British horses, wrote to the British Medical Journal predicting an imminent outbreak in humans, a forecast which shortly proved true.46 During the 1918–1919 pandemic, monkeys and baboons perished in great numbers in South Africa and Madagascar, sheep in northwest England, horses in France, moose in northern Canada, and buffalo in Yellowstone.47 There is no mystery here. We are not catching the flu from animals, nor they from us. If influenza is caused by abnormal electromagnetic conditions in the atmosphere, then it affects all living things at the same time, including living things that don’t share the same viruses or live closely with one another.

The obstacle to unmasking the stranger that is influenza is the fact that it is two different things. Influenza is a virus and it is also a clinical illness. The confusion comes about because since 1933, human influenza has been defined by the organism that was discovered in that year, and not by clinical symptoms. If an epidemic strikes, and you come down with the same disease as everyone else, but an influenza virus can’t be isolated from your throat and you don’t develop antibodies to one, then you are said not to have influenza. But the fact is that although influenza viruses are associated in some way with disease epidemics, they have never been shown to cause them.

Seventeen years of surveillance by Hope-Simpson in and around the community of Cirencester, England, revealed that despite popular belief, influenza is not readily communicated from one person to another within a household. Seventy percent of the time, even during the “Hong Kong flu” pandemic of 1968, only one person in a household would get the flu. If a second person had the flu, both often caught it on the same day, which meant that they did not catch it from each other. Sometimes different minor variants of the virus were circulating in the same village, even in the same household, and on one occasion two young brothers who shared a bed had different variants of the virus, proving that they could not have caught it from each other, or even from the same third person.48 William S. Jordan, in 1958, and P. G. Mann, in 1981, came to similar conclusions about the lack of spread within families.

Another indication that something is wrong with prevailing theories is the failure of vaccination programs. Although vaccines have been proven to confer some immunity to particular strains of flu virus, several prominent virologists have admitted over the years that vaccination has done nothing to stop epidemics and that the disease still behaves just as it did a thousand years ago.49 In fact, after reviewing 259 vaccination studies from the British Medical Journal spanning 45 years, Tom Jefferson recently concluded that influenza vaccines have had essentially no impact on any real outcomes, such as school absences, working days lost, and flu-related illnesses and deaths.50

The embarrassing secret among virologists is that from 1933 until the present day, there have been no experimental studies proving that influenza—either the virus or the disease—is ever transmitted from person to person by normal contact. As we will see in the next chapter, all efforts to experimentally transmit it from person to person, even in the middle of the most deadly disease epidemic the world has ever known, have failed.