TWO • Goddesses and World Renewal in the Ancient Mediterranean

This chapter focuses on particular patterns of mythic thought in the ancient cultures of the Near East, Egypt, and Greece in which goddesses play a central role in world renewal. It looks specifically at the figure of Innana/Ishtar of the Sumero-Akkadian traditions of the third and second millennia BCE and makes some comparisons with three other goddesses: Anat in Canaanite Ugaritic myth, Isis in Egypt, and Demeter in Greece. All of these goddesses are closely related to a beloved—a male lover or husband in the first three cases, a daughter in the fourth—who is connected with food production or rain in the face of threatened drought and whose resurrection, through the intervention of the goddess, restores life to the earth. These myths are not only about nature renewal, however. The first three have been reinterpreted in their historic forms in relationship to state formation and kingship. Thus, I also attempt to examine the difficult question of the relationship of these powerful and enduring female divine figures to the status of women in the societies that fostered their myths and cults.

INNANA/ISHTAR AND OTHER GODDESSES IN SUMERO-AKKADIAN SOCIETY

Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, has been called the “cradle of civilization.” It was here that a group of early cities emerged, bureaucracies and social hierarchies were elaborated, and religious institutions were reshaped to express the ideologies of ruling elites of temple and palace. Here writing was developed, originally as an extension of earlier forms of storage accounts for goods such as grain and oil. Between the end of the fourth millennium BCE and the middle of the third millennium, cuneiform (wedge-shaped symbols of a pictorial nature) was translated into the representation of syllables of speech and was used to record literary compositions such as hymns and myths.1

This system of writing, developed first for the Sumerian language and then used for the Semitic Akkadian language, gives us our first glimpse into the thought of an ancient people. (The earlier Sumerian culture was eventually absorbed into Akkadian society, becoming the Sumero-Akkadian culture.) Writing became highly specialized, the province of a schooled elite. Women were not admitted to these schools, even though, it is interesting to note, the Sumerian divine patron of the scribal art was the Goddess Nisaba, herself connected with grain storage.2 This link between writing and storage takes us back to the early origins of writing, in storage accounts, and perhaps to a time when women, associated with grain storage in Neolithic times, had a hand in shaping these methods of record keeping. Outside the scribal elite, most Sumerians were illiterate, yet some females did attain literacy. There was the occasional priestess writer, such as Enheduanna, appointed by her father, Sargon, as high priestess of the moon God at Ur and the author of many hymns. Some naditu (cloistered priestesses) also seem to have been trained as scribes.3

Archaeologists have pushed the history of the region back to the fifth millennium BCE, when villages began to develop, practicing a mixture of farming and animal husbandry along with hunting and plant gathering. Small temples were found in these villages, and there is evidence of some differences of wealth. The fourth millennium saw a movement toward urbanization. Larger temples became the focus of urban centers, where more specialized workers gathered. A stratified society began to take shape, with larger landowner and temple ruling elites, administrators, and accountants. Military actions brought in prisoners of war as a slave workforce. Lacking much stone or wood, early Mesopotamian society made creative use of its local resources, such as reeds and clay. Extensive agriculture was made possible by channeling the rivers into a network of irrigation ditches.4

Temple leaders used slave and corvée labor to dig and maintain these vital irrigation canals. The city elites accumulated wealth primarily through exacting tribute. A portion of agricultural produce and artisan goods, such as grain and textiles, was extracted from households, where most of the labor was done. The system of corvée labor required each household to provide a certain number of days of labor to serve the central institutions. The elites justified these exactions primarily by claiming to represent the gods, the ruling forces of the cosmos, and hence the foundations of society's collective maintenance.5 Thus, they presented the requirement of service to the gods as the destiny and common lot of all humans.

This view is reflected in the Sumerian myth of the creation of humans. According to this myth, originally the gods themselves had to do their own work, laboring to grow and harvest their food and dig the irrigation canals. The gods began to complain about this labor to Enki, the God of the sweet waters and of technological knowledge. Enki was sleeping, but he was awakened by Nammu, the primal mother who gave birth to all the gods. Enki directed the primal mother and her daughter deities to shape clay forms and turn them into living humans. These humans were charged with performing corvée service to the gods as their destined purpose for existence, and the gods were thereby freed from labor.6

This myth reflects the basic Sumerian view of the relation of humans to gods as one of servant to master. Rulers also portrayed themselves as servants of the gods. The myth reflects but also masks the emerging relationship of subjugated workers to a leisured aristocracy. The elites were freed for rule, and for military and cultural activities, by the labor of others, who contributed a portion of their products and labor to these elites.

The third millennium saw greatly expanded urbanization, with much of the population gathered in urban centers. Corvée labor was used to build monumental temples raised on high platforms and large city walls that served for defense and for displaying the power of the rulers. Competition between city-states brought chronic warfare. Military leaders, once appointed for temporary leadership in time of war, become hereditary kings with standing armies. The concentration of population in cities created a crisis in the older system of tribute that exacted a portion of the products and labor of households in the countryside. Large estates belonging to the kings, members of the royal family, high officials, and temple priests and priestesses came to control large amounts of labor and to draw on resident workforces of men and women to do the agricultural and artisan labor. These workers were paid in regular rations, in the form of allotments of grain, oil, and wool.7

Some of the workers were slaves, procured from among prisoners of war. Slave status became defined as hereditary, making their descendants permanent property of masters. Other workers owed temporary service as a result of debt: women and children could be handed over to other households to pay debts incurred by the head of a family. Most of the agricultural labor was performed not by large slave crews but by dependents who had been given allotments of land to work with their own family members, paying a portion of the produce to the estate owners.8 In contrast to the earlier tribute system, the large estates came to own the land and leased it to workers in return for produce or payment in silver.

The records of these large estates of the third millennium give us a glimpse of the class and gender hierarchy of Sumerian society. Class stratification divided the elite class of temple, royal, and wealthy estate owners from a descending hierarchy of smaller landowners, semi-free dependent labor, and slaves. Women were defined as secondary within each class, but the lives of elite women were very different from those of the poorest slave women. Sumerian society saw women as able workers and administrators. Female members of the aristocracy—wives, sisters, and daughters of kings and high officials—were appointed to administer large estates belonging to the extended family.9

Other female family members were sometimes appointed priestesses of temples, where they not only officiated in the cult but also administered the large estates of the temple. Although evidence indicates that at least two independent queens ruled in Sumerian history, women were generally excluded from the highest royal power, which was entrusted with military defense, and thus were positioned primarily to represent the extended family as priestesses in its temple holdings. Some daughters of the elite became naditu, cloistered priestesses who did not marry and lived together in households in a walled compound. This institution seems to have developed partly as a way of keeping land that had been given to daughters within the family, by endowing temple lands that then remained under family control. A naditu could not marry or bear children but could adopt a son, who then belonged to her paternal line. She also engaged in business activities.10

One has less of a glimpse of middle-level women in Sumerian society, but records of property transactions show that they had legal rights and could sell and buy land. The poorest women, female slaves, are documented primarily through estate accounts that record their labor in large workshops that produced textiles. These women did not have independent households and were not given allotments of land. Their small children worked with them, though males were excluded when they reached adolescence. Ration records indicate that these women were the lowest paid, being given thirty to forty liters of barley monthly, with ten to twenty liters per child according to age, while male slaves received sixty or more liters and were often allowed time and land to produce their own goods for market.11 Women slaves also performed other tasks on estates, such as milling grain, but the primary female sphere of labor involved textiles, in all stages of production. Spinning and weaving became closely associated with the definition of womanhood.

Thorkild Jacobsen, leading interpreter of Sumero-Akkadian religion, observes that the concept of the gods evolved through several stages that reflected changes in society.12 In the fourth millennium, the gods were seen primarily as the vital power in natural phenomena—sky and earth, the power of the spring rains, the fertilizing power of the rivers, the sap that rises in growing plants, the shaping of the embryo in the womb, the sexual attraction that generates life. Each local village and region had its own array of deities that embodied the natural powers around them. The centralizing of villages into cities, and city-states into coalitions and empires, eventually connected these many deities into a more schematic pantheon. The gods of each city, including that city's patron deity, were believed to gather in a ruling assembly, where cosmic decisions were made. The shaping of these theories of the gods as a cosmic system and polity was likely the work of the temple scribal intelligentsia. But the names for the gods remained myriad, and the relations of the gods shifted as new cities rose to power and claimed supremacy for their patron god or goddess.

The concepts of the relations among the gods were shaped through several key social metaphors. One of these was the extended family. The pantheon of the gods resembled a family with an originating pair of parents, father and mother, who brought forth daughters and sons who, in turn, married and generated children and grandchildren. The original pair was represented by Sky (An) and Earth (Ki). Nammu, the Goddess of the watery deep, can also be portrayed as the original mother of the gods, from whom all the other gods were born. Ninhursag, representing the power of the ground and of wildlife in the hills and seen as the birthing Goddess, was also among the primal circle of deities. The offspring of the primal pair were Enhil, associated with the power of the wind and representative of his father, An, in lordship over the world system; and his younger brother, Enki, associated with the power of sweet waters and technological cunning.13

Enhil and his wife, Ninlil, associated with air and wind and patrons of the city of Nippur, were the parents of the moon God and Goddess, Nanna and Ningal. From the moon was born the sun God, Utu, as well as his sister Inanna, associated with love and the evening and morning stars. The counterpart to these deities of sky, air, water, and earth was the underworld, the realm of the dead, originally seen as ruled by the powerful Goddess Ereshkigal. Like many royal families, the family of the gods was quarrelsome, with younger members vying to equal and replace the power of their elders.

Another social metaphor for the relationships among the gods was based on the administrative staff of great temple estates. The patron god or goddess was viewed as the owner of the estate, served by a large bureaucracy of deities that mirrored the human bureaucracy. Certain gods fulfilled the roles of high constable, steward, chamberlain, and military protector. Lesser deities prepared the god's bath, bed, and meals; sang and played music; brought petitions; and carried the god on journeys. Others supervised the plowing and harvesting of fields and the care of fisheries, flocks, and wildlife. The entire cosmos, then, could be seen as the extended estates of a divine royal family, with various deities appointed to specific offices. This metaphor signaled a change in the relation of the gods to natural phenomena. Earlier, people had conceived of gods and goddesses as immanent within natural phenomena; now these phenomena came to be seen as spheres of administration, to which the gods were appointed by a divine lord and his representative.14

This concept is reflected in the myth of Enki, known as the organizer of the cosmic system on behalf of his father, An. First, Enki organizes the various lands and peoples and decrees their respective fates. He then turns to the various spheres of human needs. After filling the Tigris and Euphrates with fertilizing waters ejaculated from his penis, Enki puts the rivers under the God Enbilulu, inspector of canals. Enki appoints a fish deity to control the marshes, a sea goddess to control the sea, and a rain god to control the waters of the heavens. The fields and plowing, the tools of house construction, the wildlife of the steppes, the sheepfolds, and the textile industry are likewise put under the control of their respective deities. After organizing the administrative system of the cosmos, Enki is then challenged by Enhil's ambitious granddaughter Inanna, who complains that he has given her no sphere of administration. Enki replies that he has already given her a vast sphere that encompasses the power of kings in both love and war.15

Inanna's ambition for an enlarged sphere of rule is also portrayed in a second myth, which involves Enki, patron of the city of Eridu. In this story, Inanna sets out to visit Enki in Eridu. He welcomes her, and the two settle down to a prolonged drinking bout. In his drunken state, Enki proceeds to promise Inanna a series of me, cosmic spheres of power such as rulership, religious office, descent and ascent from the underworld, sexual arts, powerful speech, musical arts, military power, crafts, and others. Inanna gathers in each group of me, amassing a total of fourteen groups. She then takes them all and departs in her boat to return to her city of Erech. Enki, recovering from his drunken state, realizes what he has done and tries to prevent Inanna from reaching her city by sending a series of monstrous beings to stop her. But Inanna defeats each attack and arrives home triumphantly, thus justifying the restoration of her city to its supremacy in the Sumerian coalition. Enki ends by conceding the regained supremacy of Erech.16

Another key metaphor for relations among the gods was the political assembly in which leaders of each city in the Sumerian coalition met, gathering in the holy city of Nippur to appoint a king during military crises. The gods thus came to be seen as a political and juridical assembly that appointed or dismissed kings and decreed the fates of cities in war. The gods themselves were imagined as kings, warriors, and judges. They rode out in battle and judged appeals that were brought to them, ruling on cases involving other gods as well as humans. The wild and arbitrary powers of storm and flood in nature were fused with the devastating violence of war, both represented by gods. Before these arbitrary powers, humans could only weep and lament, hoping to avert divine wrath, but ultimately were forced to bow to the fate that the gods decreed.17

The development of these metaphors, from natural powers to extended family, estate management, and political assembly—themselves reflections of the increasingly hierarchical centralization of society—seems to have had various effects on the status of female deities in the divine pantheon. The earliest metaphors of immanent natural powers suggested parallel gods and goddesses, with the gender of deities associated with sky, earth, plants, animals, and waters often fluid, as nature itself demands a fluid interchange of male and female powers. The family metaphor also required equal numbers of female and male members: father and mother, sister and brother, daughters and sons. But the later myths had a tendency to marginalize the goddesses as wives. They became shadowy auxiliaries to dominant gods rather than distinct personalities in their own right. The metaphor of the political assembly marginalized goddesses even more. Upper-class women may have administered estates, but they were not members of the military and political assemblies.18

Three sets of myths express the marginalization of specific goddesses in the pantheon. One involves the rivalry of Enki and Ninhursag, Goddess of wildlife and birth. In the original pantheon, Ninhursag is third in ruling status, next to the father, An, and his son Enhil (Ki and Nammu, the primal mothers, already have become shadowy in this scheme). Enki wishes to displace Ninhursag and take her place as the third in rank. He challenges her to various contests. In one story, he impregnates her and then seduces and impregnates her daughter and granddaughter. He tries to repeat this with her great-granddaughter, but Ninhursag blocks this until he brings gifts. She then punishes Enki by implanting in him a series of herbs that cause him to fall gravely ill. She finally relents and brings forth from him eight healing deities. In another contest, Enki claims that for each human that Ninmah (Ninhursag) creates with various handicaps, such as blindness and deafness, he will find a job in society. But then Ninmah is unable to find a job for a particularly deformed creature created by Enki.19 The upshot of these tales of rivalry between Enki and Ninhursag is that she is displaced and he becomes third in the pantheon. This downsizing of Ninhursag perhaps itself reflected a privatizing of the female powers of birth and household management vis-à-vis the public power of male administration and rule.

A second Goddess who became marginalized in Sumero-Akkadian tradition was Ereshkigal, ruler of the underworld. In early myths, she rules this realm alone; but in a later story, she is forced to accept a husband, Nergal, formerly a celestial God. In this story, Ereshkigal is invited to partake in a feast held by the gods in the heavenly world. She sends a representative to bring her some delicacies, but one God, Nergal, refuses to offer her deputy his respects. Ereshkigal demands that Nergal be sent to the underworld so that she can kill him. But when Nergal arrives, he grabs her by the hair, pulls her from her throne, and throws her on the ground to kill her. She pleads for her life, offering him marriage and rule over the underworld. Ereshkigal then becomes a dependent wife under the control of her husband.20

The most significant myth of male divine power displacing the female occurs in the Babylonian creation story, the Enuma Elish. This story in its extant form was probably shaped in the Old Babylonian period, in the early second millennium BCE, to herald the ascendancy of the God Marduk, patron of Babylonia, over the more ancient deities. The story begins with the emergence of creation from the primordial mother, Mummu-Tiamat, and her consort Apsu, representing the commingled waters from which all life emerged. From this pair, successive generations of gods and goddesses come forth. Then a conflict arises between the primordial mother, Tiamat, and the younger gods. Tiamat seeks to avenge the death of Apsu. She rallies the ancient gods, portrayed as monstrous powers of chaos that threaten the new order of the younger gods.

The divine assembly meets and appoints Marduk as its champion. Marduk then goes out and defeats Tiamat in single combat. He splits her body in half, using one half to shape the sky and the other half the earth below. After shaping the cosmos out of the dead body of Tiamat, Marduk then sacrifices her second consort, Kingu, and from his blood mixed with clay creates humans to serve the gods, relieving the gods of the need to labor.21 This creation myth, designed to justify the ascendancy of Marduk over the other gods, pictures the ancient world of the divine as originating in and led by a powerful primordial goddess who is overthrown and dismembered, her body becoming the matter shaped by the male warrior god into the present cosmic order.

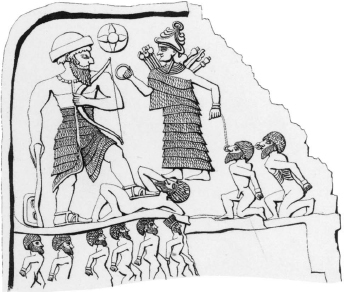

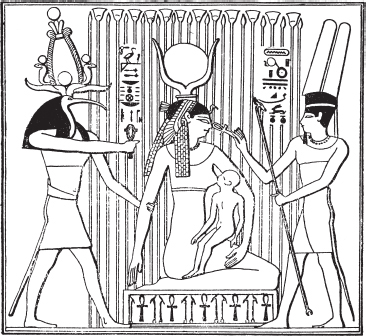

Despite these stories that marginalized goddesses (and perhaps reflected the increasingly subordinate position of women vis-à-vis the males of their families in second-millennium Babylonian law and society),22 goddesses did not disappear from the imagination of divine power. Indeed, one, the Goddess Inanna, seemed to rise and take on expanded power—witness the tales of her complaints to Enki over his failure to give her a large enough sphere of power in the cosmos and her daring appropriation of the me, which she carried back to her city of Erech. In Sumero-Akkadian myth, Inanna (her Akkadian name is Ishtar) was typically pictured as impetuous, imperious, ambitious, ready to fight for her own prerogatives, and generally succeeding in her exploits (fig. 7). Her ascendancy owed something to Sargon, ruler of Akkad, who sought to create a united empire of Sumer and Akkad under his hegemony shortly after 2350 BCE.

FIGURE 7

The Goddess Inanna, with signs of her ruling power, her foot on the back of a lion, 2334–2154 BCE. Cylinder seal, Mesopotamia. (Courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago)

Sargon shaped an Inanna/Ishtar royal myth to validate his own rise to power. According to one legend, Sargon was the son of a priestess and an unknown father. In a story that was perhaps later adapted to Moses in Hebrew scripture, his mother put the baby in a basket of rushes and set it adrift on a river. The baby was picked up and raised by Akki, a drawer of water, who made the boy his gardener. In that capacity, Sargon became the lover of Ishtar,23 a story that reflects the myth of the sacred marriage, in which Inanna mates with a gardener. (This was a kingly title, for the king was seen as a shepherd and also as a gardener or farmer, key economic roles. In the temple, the king or priest poured the Waters of Life on the Tree of Life.) Sargon thus positioned himself as one put on the throne through union with Ishtar.

Sargon consolidated his power over Sumer by naming his brilliant daughter, Enheduanna, as high priestess of Ur. From this princess-priestess, we have a cycle of hymns to Inanna that express the royal ideology of the new dynasty. In her long poem on Inanna's exaltation, Enheduanna praises the Goddess as the “lady of all the me” (governing powers) and an equal to An, the sky father. Her image is all powerful, uniting the uncontrollable forces of storms and war: “In the van of battle, everything is struck down by you… in the guise of a charging storm, you charge, with a roaring storm you roar.” All the other gods flutter away like bats before Inanna's powerful advent.24

Enheduanna then laments her own displacement from her position as priestess of Ur during an uprising against her father's rule. But the hymn ends with the confident hope that her position will be restored, even as Inanna's power will be exalted throughout the earth: “That you are lofty as Heaven, be known! That you are broad as earth, be known! That you devastate the rebellious land, be known!... that you attain victory, be known! [That,] Oh my lady, has made you great, you alone are exalted.”25

Inanna owed her continued importance not only to her exaltation as patron of the Sumero-Akkadian dynasty of Sargon. That exaltation itself was rooted in her identification with two key mythic cycles central to kingship ideology: namely, the sacred marriage, and the descent and ascent from the underworld. Inanna incarnates heated female sexuality. She is the female side of courtship and sexual union, but never the dutiful wife or mother. She does not patronize motherhood, child care, or weaving. She establishes kings on their thrones, but she does so as a nubile bride who never becomes a submissive wife. In the poems of the courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi, we see Inanna in her relationship to the courting bridegroom.

Inanna's brother, the sun God Utu, initiates the courtship by telling her that he will bring her the bridal bedsheet of woven flax. He then introduces Dumuzi the shepherd as the prospective bridegroom, but Inanna dismisses the thought of marriage to a shepherd (seen by Sumerian society as a semi-nomadic, uncivilized bumpkin). She demands a farmer as her husband, someone who can fill her storehouses with heaped-up grain. Utu argues that the produce of the shepherd is equally valuable. Dumuzi then speaks, comparing his produce with that of the farmer. If the farmer brings black flour, Dumuzi will bring black wool. If the farmer brings white flour, he will bring white wool. If the farmer brings beer, he will bring sweet milk. If the farmer brings bread, he will bring honey cheese.26

FIGURE 8

The courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi, Old Babylonian period, c. 2000–1600BCE. Clay plaque, Mesopotamia. (Photo: Erlenmeyer Collection, Basel)

Dumuzi then arrives at Inanna's door with his gifts, and Ningal, Inanna's mother, persuades her to accept him. Inanna then prepares herself for the marriage bed with scented oils, white robe, and precious jewelry. Inanna cries out in delight in her expectation of sexual pleasure, using the metaphors of a plowman plowing a field ripe for planting: “Who will plow my vulva? Who will plow my high field? Who will plow my wet ground?... Who will station the ox there?” Dumuzi declares that he indeed will plow her vulva, to which Inanna replies: “Then plow my vulva, man of my heart, plow my vulva” (fig. 8).27

In the scene of sexual union that follows, we see the fusion of agricultural luxuriance with the establishment of a king on his throne through his union with Inanna. “Plants grew high by their side. Grains grew high by their side. Gardens flourished luxuriantly.” Dumuzi is the fertilizing power that makes the plants burgeon, while Inanna is the field that pours out grain. Dumuzi hymns, “O Lady, your breast is your field. Inanna, your breast is your field. Your broad field pours out plants. Your broad field pours out grain.” Agricultural wealth, not a human child, is the anticipated outcome of this sexual union. This outpouring of food culminates in Inanna's enthronement of Dumuzi as king: “The Queen of Heaven, the heroic woman, greater than her mother, who was presented with the me by Enki, Inanna, the first daughter of the Moon, decreed the fate of Dumuzi.” Inanna gives Dumuzi both military victory and kingly power (figs. 9 and 10):

FIGURE 9

Inanna, riding ahead of a war chariot, Akkad period. Cylinder seal, Mesopotamia. (Collection of Pierpont Morgan Library, New York)

In battle I am your leader… on the campaign I am your inspiration... you the king, the faithful provider of Uruk… in all ways fit: to hold your head high on the lofty dais, to sit on the lapis lazuli throne, to cover your head with the holy crown, to wear long clothes on your body, to bind yourself with the garments of kingship, to carry the mace and the sword... you the sprinter, the chosen shepherd, in all ways are you fit. May your heart enjoy long days.

Assured of this outcome, Dumuzi proceeds to the sacred union with Inanna: “The king went with lifted head to the holy loins. He went with lifted head to the loins of Inanna. He went to the queen with lifted head. He opened wide his arms to the holy priestess of heaven.”28

FIGURE 10

Inanna/Ishtar, as Goddess of war, bringing captives to the king, 2300 BCE. Drawing from a clay tablet. (From Andrew Harvey and Anne Baring, The Divine Feminine [York Beach, Maine: Conari Press, 1996])

Though established on the throne by Inanna and assured of an outpouring of agricultural prosperity, Dumuzi find that his days are numbered. As the vitality of natural life, he dies with the searing heat of summer that kills the foliage and brings a long drought, during which the populace waits anxiously for the new rains that will allow new growth. The relation of Dumuzi to the dying and rising vegetation is reflected in the greatest of the Inanna myths, her descent to the underworld. In the Sumerian and Akkadian versions of this myth, it is Inanna who initiates the descent and thereby threatens the life of nature, while Dumuzi functions only as her forced surrogate.

Inanna undertakes this descent as an expression of her ambition, her desire to add the realm of the underworld, ruled by her sister Ereshkigal, to her own realms of power in heaven and earth. “From the great above the goddess opened her ear to the great below.... My Lady abandoned heaven and earth to descend to the underworld.”29 But lest she be defeated in her goal and be unable to return, Inanna alerts her servant Ninshubur to intervene for her with the elder gods Enhil, Nanna, and Enki. Inanna then proceeds through the seven gates of the underworld. At each gate, she knocks and demands to enter but is allowed to pass through only by being stripped, piece by piece, of the royal regalia that signifies her powers: her crown, her jewelry, her breastplate, her gold ring, her measuring rod and line, and finally her royal robe.

Naked and bowed low, Inanna enters the throne room of her sister Ereshkigal. There, she is judged by the Annuna, the judges of the underworld. Ereshkigal fixes her with the “eye of death” and turns her into a corpse, which she hangs from a hook on the wall like a piece of rotting meat. When Inanna fails to return, her faithful servant Ninshubur begins a lament for her and makes the rounds of the gods to intervene on her behalf. Enhil and Nanna ignore Ninshubur's pleas, but crafty Enki is willing to help. He fashions two sexually neutral creatures from the dirt of his fingernails and sends them to the underworld to aid Ereshkigal, who is moaning like a woman in labor. The two creatures offer to relieve her pains and in return demand the corpse of Inanna. In gratitude for their help, Ereshkigal releases the corpse of Inanna; but Inanna, now revived, cannot ascend back to the world above without providing a surrogate.

As Inanna emerges, she looks for a suitable substitute. She rejects the idea of using her faithful servant Ninshubur, who has saved her. She also refuses to send her two children, Shara and Lulal, who have mourned her absence. But then her eye fixes on her husband, Dumuzi, who has not mourned her but instead is enjoying the powers of kingship, “dressed in his shining me-garments. He sat on his magnificent throne.” Falling into a rage at his uncaring behavior, “Inanna fastened on Dumuzi the eye of death. She spoke against him the word of wrath. She uttered against him the cry of guilt: Take him! Take Dumuzi away.”30 The story continues with the intervention of Dumuzi's loving sister Geshtianna, who seeks to save him. Through her efforts, Dumuzi's fate is modified. He will remain in the underworld only part of the year (the drought season) and during the rest of the year may ascend again. When he ascends, new life will be restored to the earth.

The figure of Inanna is fascinating to contemporary feminists seeking ancient goddess role models because of her autonomy, sexual enjoyment, and power. Some have asked whether she represents some prepatriarchal time when women enjoyed such power and vitality. But I believe that this is the wrong question. The image of Inanna in this ancient culture was not shaped as a “role model for women,” much less as a remembrance of powers once available to women. Rather than beginning with modern gender ideology, one must reckon with her first by understanding the Sumero-Akkadian view of deity. Inanna's power and autonomy stem from her identity as a god, not as a human woman. For the Sumerians, a vast gulf separated humans and gods. Gods were immortal, and humans mortal. In the words of the Gilgamesh epic, “Only the gods live forever under the sun. As for mankind, numbered are their days.”31

Humans were created to serve the gods with their labor. Their proper relation to the gods was praise and lament. Through praise, they hoped to win the favor of the gods; through lament, to turn away their wrath. But the gods were by nature imperious and capricious. Even kings were finally servants of the gods, knowing that, at any moment, the gods could fasten on them “the eye of death” and send them weeping into the underworld of death and decay. Prayers of praise and lament addressed to deities, whether god or goddess, thus had a similar formula.

One prayer of lament to Ishtar, probably originating in the middle of the second millennium, first addresses her by praising her greatness, particularly her power in war: “I pray to you, O Lady of Ladies, goddess of goddesses, O Ishtar, queen of all peoples, who guides mankind aright.... O most mighty princess, exalted is thy name. Thou indeed are the light of heaven and earth, O valiant daughter of Suen [the moon], who determines battle.”32

Having thus exalted Ishtar as the greatest of the gods, the lamenter then pours out his troubles to her in a fashion familiar to us from the Hebrew psalms, which were modeled on these Babylonian hymns. (I use the term “his” for the lamenter because the economic and political nature of his misfortunes reflects primarily the reality of powerful males, not that of women or poorer men.) The lamenter describes his sickness, his misfortunes, the conspiracy of his foes against him. He then pleads that any mistakes he has committed be revealed to him and asks to be forgiven: “Forgive my sin, my iniquity, my shameful deeds and my offense. Overlook my shameful deeds, accept my prayer, loosen my fetters, secure my deliverance.” He begs that her wrath be averted: “How long, O my Lady, will thou be angered so that thy face is turned away?” The prayer ends with hopes that the Goddess will turn back to him and restore his fortunes so that he can once again prosper and triumph over his enemies: “My foes like the ground let me trample.” The hymn ends with final words of praise: “The lady indeed is exalted, the Lady indeed is Queen, Irnini, the valorous daughter of Suen, has no rival.”33

As an immortal, no god or goddess can be literally a “role model” for humans, yet these deities were also shaped as immortal “projections,” to use a modern term, of the power and behavior of kings (and occasionally queens). Royal power was dimly reflected in the all-dominating power of gods, but always as temporary and always through acknowledgment of the rulers' dependency on and servitude to their patron deity. Any human woman who might have attempted to emulate Inanna would have been a powerful queen or a royal priestess, not an ordinary woman, just as the relation of rulers to ruled was modeled after the relation of gods to humans. Inanna was the Goddess of kings and queens, of powerful men and exceptional royal women, not a Goddess from which ordinary women could expect much succor in their daily lives as they struggled with childbirth, healing, or the toil of spinning and weaving. Here, a Goddess such as Ninhursag would be more the helper.

The figure of Inanna does have an aspect of carnival, of times of celebration in which the normal hierarchies of class and gender were dismantled and the limits and order of society breached. At such times, all women and men in society could join in celebration of Inanna. The wearing of transgendered clothes by her devotees reflects this time of upset of normal boundaries. But this aspect of Inanna's cult functioned as a temporary relief of class and gender separations, not a real change in these divisions.34

The combination of Inanna's divine power and sexual femaleness is linked to kingship ideology. Here, I believe the liminality of Inanna is important. As sexually aggressive, as the “hot” courtesan who attracts the male lover (but would be dangerous and inappropriate as a wife), Inanna also mediates between the divine and the human worlds. One probably should not interpret this as an indication that “sacred prostitution” was practiced in Sumero-Akkadian temples. How sacred marriage itself was enacted ritually also needs more study. Since the high priestess was herself often a mother, daughter, or sister of a king, it is not certain that such a marriage was always performed in a literally sexual way.35

Rather, we should see Inanna's sexuality as expressing the power through which the divine as female touched the highest ranks of the male human world, the realm of kings. Through marriage to her, kings were exalted, put on the lapis lazuli throne, and vested with the powers of rule. Kings could never become immortal, although some might have briefly pretended to be. They were, finally, humans and shared the common fate of humans, death. But through marriage to Inanna, kings could temporarily imagine themselves to be like gods, sharing in their power and glory. It is this boundary role of Inanna that helps to explain not only her contradictions but also her centrality for Sumerian royal mythology.

ANAT IN UGARITIC MYTH

The figure of Anat in Ugaritic myth both resembles and differs from that of Innana/Ishtar in Sumero-Akkadian myth. Anat too is a war Goddess, with an aggressive, impetuous personality, and is linked to kingship ideology. Ugaritic myths were uncovered between 1929 and 1932 in the excavations of ancient Ugarit, a city on the Syrian coast that flourished between 1500 and 1200 BCE. The many tablets found in these excavations are in seven languages—Akkadian, Cypro-Minoan, Egyptian, Hittite, Hurrian, Sumerian, and Ugaritic—testifying to the city's role as a center of international trade.36

The Ugaritic language was quickly deciphered because of its affinities to early Hebrew. The tablets include trade and tax lists, diplomatic letters, and lists of sacrifices to be performed to different deities at different times of the month.37 Most important for our purposes is a series of mythological texts. Anat plays a key role in those texts in relation to the fortunes of Baal, the storm God, and in the story of the birth and death of the hero Aqhat. This discussion analyzes her nature and role by focusing on these two groups of texts.

The stories of the fortunes of Baal were edited by the scribe Ilimilku, apparently as part of the efforts to establish the claims of King Niqmad II to the throne.38 The composition brings together groups of material copied from earlier tablets. The fragmentary nature of many of the surviving tablets makes it difficult to interpret some of the story. Overall, the Baal texts fall into three main sections. The first recounts the struggle between Baal and Yam, the God of the sea, in which Baal emerges victorious. The second involves the struggle to establish Baal's “house,” or temple, and his sovereignty among the gods. In the third sequence, Baal is defeated by Mot, the God of death and the underworld. Anat searches for his body, recovers it, and performs the funerary rites. Baal is then restored to life and power.

The major deities in these stories are El, the father God, and Athirat-of-the-sea (Asherah), his wife and progenitress of the gods, and their three major offspring, Yam, Mot, and Anat. Baal is described as the “son of Dagan,” a Hurrian God, although sometimes he is also called the son of El. His struggle for sovereignty perhaps reflects the effort to integrate the God of the Hurrian people into the Ugaritic pantheon.39 In the first sequence, on the struggle of Baal and Yam, El initially favors Yam and declares his enthronement as king. Baal is enraged, attacks and kills Yam, and establishes his own rule. Anat appears at the beginning of these texts, when her father, El, summons her as the war Goddess to “grasp your spear and your mace, let your feet hasten to me,... bury war in the earth, set strife in the dust,... pour a libation into the midst of the earth.”40 These activities set the stage for Yam's intended coronation.

In the second sequence, on the establishment of Baal's house, Anat plays a central role as Baal's advocate. There is a feast for Baal in his palace. Anat is then described in terms of her activities as a war Goddess. She embodies the frenzy of battle that rages between two towns. Decapitated heads pile up beneath her, and she decks herself with severed hands and heads. She wades in the gore of warriors to her knees. This scene of warfare is then repeated in her temple. Here, she ritually sets up chairs and tables as representatives of armies and again steeps herself in the frenzy of war: “Her liver shook with laughter, her heart was filled with joy, the liver of Anat with triumph.”41 Her palace is then purified of the blood of soldiers, including her act of washing her hands in the blood of warriors. This second ritual war in her palace perhaps has to do with the cultic establishment of her victory and the conditions of peace (fig. 11).42

Baal meanwhile is strumming his lyre amid his wives. He sends a commission to Anat, asking her to establish conditions of victorious peace. Again, as in the summoning of Anat by El, Anat is called to come with these words: “Bury war in the earth; set strife in the dust, pour a libation into the midst of the earth... grasp your spear and your mace, let your feet hasten toward me.” Anat is at first fearful that Baal has suffered some setback in his struggle for sovereignty. She cries out, “What manner of enemy has arisen against Baal, what foe against the Charioteer of the clouds?” She asks if she has not already defeated Yam and other foes of Baal: “Surely I smote the Beloved of El, Yam? Surely I exterminated Nahar, the mighty god? Surely I lifted up the dragon, I overpowered him?”43

Baal's messengers assure her that no new foes have arisen against Baal and that he summons her to establish conditions of victorious peace. Anat agrees to come, again claiming that she will “bury war in the earth.” At the arrival of “his sister,” “his father's daughter,” Baal dismisses his harem. He sets a feast before her, while she purifies herself: “He set an ox before her, a fat ram in front of her. She drew water and washed herself with the dew of heaven... she made herself beautiful.”44

A missing section may have contained a scene of sexual copulation between the two. Other text fragments describe Baal as he sees Anat approaching and then as he bows before her. There follows a vision of cows mating and giving birth. Baal exclaims, “Like our progenitor I shall mount you.” “Baal advanced, his penis tumescent,” while “moist was the nethermouth [vagina] of Anat.” In another fragment, the sexual congress of the two is described in this way: “Baal was aroused and grasped her by the belly [vagina]; Anat was aroused and grasped him by the penis”... “Embrace, conceive and give birth.”45 Clearly, part of the relation of Baal and Anat is one of sexual delight, bringing fertile birth.46 This relation is described in cattle imagery: Baal as a bull, the birthing ones as cows, the offspring a young male heifer. These images express the hopes for the power and wealth of kings.

Baal then complains to Anat that, unlike the other gods, he has no house. Anat vows to intervene with her father, El, threatening to thrash him if he does not accede to her demands: “I will make his gray hair run with blood, the gray hair of his beard with gore, if he does not give a house to Baal like the gods.” Anat then “stamped her feet and the earth shook; she set her face toward El.”47 Arriving at El's sanctuary, she repeats her threats. El mollifies her, declaring that he knows her to be implacable. Baal and Anat then appeal to Athirat, asking her to intervene with El to build a house for Baal. Athirat journeys to El's tent and makes this appeal: “Your word, El, is wise, you are everlastingly wise, a life of good fortune is your word.” Athirat then calls for Baal's sovereignty: “Our king is Valiant, Baal is our Lord and there is none above him.” Once in power, Baal will ensure abundant rain: “And now the season of his rains may Baal appoint, the season of his storm-chariot.”48

FIGURE 11

The Goddess Anat on a war chariot, second millennium BCE. Stone stele. (Private collection, Cairo)

El accepts this appeal, and Anat goes to tell Baal. “Virgin Anat rejoiced: she stamped her feet and the earth shook. Then she set her face toward Baal.... Virgin Anat laughed: she lifted up her voice and cried, Rejoice, Baal, good news I bring.” A vast palace of silver and gold is then erected for Baal, and sacrifices and feats are performed to dedicate it. Baal tours his kingdom and throws down a challenge to his remaining enemy, Mot, the God of death, declaring that “I alone, it is who will rule over the gods.”49

The third section of the Baal texts portrays this struggle between Mot and Baal, in which Anat plays a key role. Mot declares that because he did not receive an invitation to Baal's feast, he will devour Baal and bring him down into the netherworld of death. Baal trembles with fear and declares himself Mot's servant. Baal descends to earth and seeks to ensure his progeny by lying with a heifer, who bears him a young male. He then descends into the underworld. A cry is set up: “Dead was Valiant Baal, perished was the Prince, the Lord of the earth.” El descends from his throne and sits on the ground, pouring ashes on his head and gashing himself in rites of mourning.50

Now it is Anat's turn to seek out Baal. She searches to the ends of the earth, going down into the underworld beyond the shores of death. There, Baal is found. She too performs rites of mourning, weeping and gashing herself. With the help of an assistant, Anat lifts Baal onto her shoulders and takes him to “the uttermost parts of Saphon,” the holy mountain of the gods, where she performs the funerary rites, slaughtering groups of seventy bulls, oxen, sheep, stags, goats, and antelope.51

Anat's feelings of compassion for Baal are described as maternal: “Like the heart of a cow for her calf,... so the heart of Anat went out to Baal.” She seizes and destroys Mot, her actions described in language reminiscent of a harvesting rite: “With a knife she split him, with a fan she winnowed him, with fire she burned him, with millstones she ground him, with a sieve she sifted him, in the field she sowed him, in the sea she sowed him.”52

This ritual destruction of Mot is followed by El's vision of Baal's resurrection and the restoration of fertilizing rains to the earth: “Let the skies rain oil, let the wadis run with honey. And then I shall know that Valiant Baal is alive, that the Prince, Lord of the earth, exists.”53 Baal arises, is enthroned, and claims domination: “And Baal went up to the throne of his kingship.” But Mot, not quite defeated, reemerges and complains of his treatment by Anat. After a struggle with Baal, Mot finally accepts Baal's dominion: “Let Baal be installed on the throne of his kingship.”54

The story of the hero Aqhat, recounted in the second group of texts, reveals a different side of Anat's personality. The good king Daniel had prayed to the gods for a son and received a heroic boy, who is given a special bow and a set of arrows by the gods. Anat covets this bow and demands that Aqhat give it to her, promising him gold and silver and then immortal life. But Aqhat scorns her, declaring that he knows mortality is his lot as a human and that bows are for males, not females. As a huntress Goddess, Anat is affronted, and she arranges to kill Aqhat, an action that she then regrets. Aqhat's death brings a period of infertility to the land. His sister sets out to avenge him by killing the vulture that killed her brother.55 It is possible that the hero is then resurrected and restored to his father, but that ending is missing from our tablets.56

With these two sets of stories, what can we say of Anat's role and personality? Anat is violent and war-loving, yet she also establishes conditions of peace in the land. She is imperious yet fiercely loyal to her beloved Baal. She is sexual and brings forth offspring without ever ceasing to be a maiden. She is not Baal's wife, but his companion, what Latin Americans call a compañera,57 although in the story of Aqhat she acts independently and against Baal's interests and is put in a questionable position as a result. In the Baal poems, she is his advocate, establishing his sovereignty and restoring him to life by rescuing his body, performing the funerary rites, and defeating his enemies. Like Inanna/Ishtar, she is the power behind the throne, both the throne of Baal and that of the king as representative of Baal. Through her, the kings of Ugarit are assured of their dominion, of the fertilizing rains on which agricultural plenty is based.

ISIS OF EGYPT

The figure of the Egyptian Goddess Isis developed over three thousand years, from before the first dynastic period (3000 BCE). In the Ptolemaic period (the reign of the Greek kings of Egypt, who ruled from 323 to 30 BCE), the cult of Isis and Osiris was reshaped as a mystery religion, similar to the Eleusinian mysteries, and became a religion of personal salvation disseminated throughout the Greco-Roman world.58 Chapter 4 takes up this later phase of the story of Isis. Here, I attempt to sketch something of the figure of Isis before her Hellenistic transformation. This task is difficult because we have no complete Egyptian text of the story of Osiris's death and his restoration by Isis. This tale is found only in a heavily hellenized version by Plutarch, written in the early second century CE. 59

In the cosmology shaped at the religious center of Heliopolis in the early dynastic period, Isis and Osiris belonged to the fourth generation of the gods. Creation was envisioned as emerging from the primal waters in the form of a hillock, much as the fertile hillocks of mud, on which Egypt's agricultural life depends, emerge from the annual inundation by the Nile. This original hillock was Atum, the creator. From him was brought forth the male God Shu (air, light) and the female Tefnut (moisture); they in turn brought forth the God Geb (earth) and the Goddess Nut (sky), who were separated from each other by Shu. From Geb and Nut came two pairs of gods and goddesses, Osiris and Isis, Seth and Nephthys. These nine made up the great gods, or the Ennead (to which was sometimes added an elder Horus).60

Isis and Osiris were said to have loved each other from their mother's womb, while Seth was depicted as the adversarial brother who seeks to kill Osiris and claim the sovereignty of Egypt. Nephthys, although said to be Seth's wife, acted as a helper and was the twin sister of Isis. The two were paired at the head and foot of the bier of the dead Osiris, at the head and foot of the sarcophagi of pharaohs, and on the doors leading to tombs, as two goddesses who assured the dead pharaoh, identified with Osiris, of life after death.61 Isis carried on her head the symbol of the royal throne, while Nephthys bore the symbol of the palace.62 Thus, together, they represented the basis for kingly power, the house in which the pharaoh was enshrined, the seat upon which he was enthroned.

FIGURE 12

The Goddess Isis in her aspect as amother, suckling an infant pharaoh, Ptolemaic period. Small statue. (Museo Gregoriano Egizio, Vatican Museums, Vatican State; photo: Scala/Art Resource, NY)

Isis, as the wife of the dead king resurrected into immortal life, was the mother of the living king, Horus, whom she generated from the dead body of her husband-brother, Osiris. The throne from which the pharaoh reigned was the lap of Isis, upon which he was seated as a baby, nourished by her milk. In contrast to Inanna and Anat, wifely and maternal devotion were central to the nature of Isis. A favorite image of Isis and Horus shows the young king seated on her lap as she suckles him from her breast (fig. 12),63 an image that would be taken over into Christianity as the image of Mary suckling the baby Jesus on her lap.

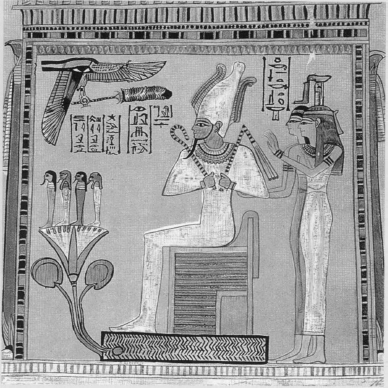

FIGURE 13

Isis and Nephthys stand behind Osiris, who sits on the throne, c. 1310 BCE. Painting, Book of the Dead of Hunefer. (From Andrew Harvey and Anne Baring, The Divine Feminine [York Beach, Maine: Conari Press, 1996])

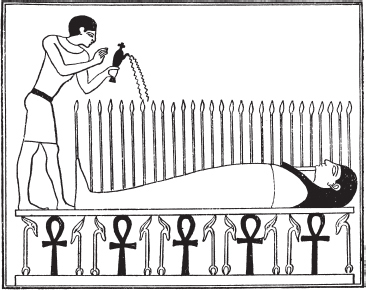

Osiris, as king of the dead, presided over the hall of judgment into which each dead person was led. Each individual's heart was weighed to see whether he or she was worthy of being reborn to immortal life. Isis and Nephthys typically stood behind the enthroned Osiris, supporting him (fig. 13).64 In the early dynastic period, Osiris also became identified with the new grain that rises from the earth, fructified by the Nile's waters. He is pictured lying as a mummy beneath the grain, which sprouts from his body, while a priest pours water on him (fig. 14). Mats of earth with sprouting grain were placed in the tombs of the dead, thus making the connection between the grain that rises yearly from the earth and immortal life that rises in the resurrected Osiris.65 A similar identification of the seed that “dies” in the earth only to rise as the new grain and the body resurrected to immortal life is used by Paul in the New Testament (1 Cor. 15:37–38).

FIGURE 14

Osiris with wheat growing from his body, watered by a priest, with the ankh life-sign and the was-scepter of divine prosperity beneath him, Ptolemaic period. Bas-relief, Ptolemaic Temple of Isis at Philae. (From Ernest Alfred Thompson Budge, Osiris: The Egyptian Religion of Resurrection [New Hyde Park, NY: University Books, 1961])

There are several versions of the death of Osiris. In a story found in the theology of Memphis, Osiris falls into the risen Nile and drowns. The young Horus entreats the Goddesses Isis and Nephthys to rescue Osiris. They draw him from the waters and install him in the Great Seat, the temple of Ptah at Memphis, called the “mistress of all life, the Granary of the God through which the sustenance of the Two Lands is prepared.” Here, Osiris is explicitly identified with the grain “drowned” in the waters of the Nile and then risen to new life. His son Horus is installed as king of the Two Lands, the northern and southern kingdoms of Egypt, “in the embrace of his father Osiris” through taking his seat in this center of control over the grain supply.66

Other versions of Osiris's death connect it to rivalry with Seth. Two successive stages of this murder are found in Plutarch's treatise on Isis and Osiris. Plutarch's account is a syncretistic conflation of Osiris with Dionysus and Isis with Demeter, read through the lens of Neoplatonic philosophy, but the core stories go back to earlier Egyptian tradition. In the first stage of the story, Tryphon (Seth) created a chest made to fit Osiris's body. He brought it into a banqueting hall and promised to give it to the person who fit inside. When Osiris lay in the chest, Seth slammed the lid and secured it with bolts and molten lead. Thrown into the Nile, it floated out to the sea, eventually washing ashore in the land of Byblos. There, a heath tree grew up around it until the chest was enclosed in its trunk. The tree was cut down and used as a pillar to support the roof of the palace owned by the king of Byblos.

Isis is depicted as wandering throughout the earth seeking the body of Osiris. She eventually reaches Byblos, where she becomes a nurse to the child of the king and queen. She then obtains the pillar and cuts out the chest containing the body of Osiris. Carrying it off with her, she opens the chest and lies on the body of Osiris, embracing him. Plutarch's account adds elements taken from the story of Demeter's quest for her daughter, Persephone. It is likely that the identification of Byblos as the place where Osiris's coffin ended up was part of a later cult of Osiris in that land.67

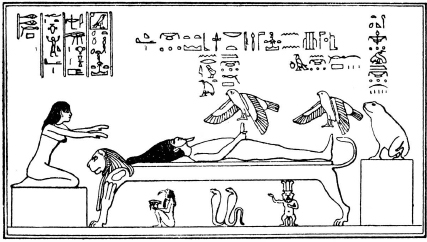

Earlier Egyptian rites seem to have enacted a play about the death of Osiris in which he was carried in a coffin. He is also identified with a pillar that is erected with the help of Isis and the pharaoh. Isis in the form of a bird is pictured as hovering over the mummified body of Osiris, whose rising life is depicted through his erect phallus (fig. 15). Isis takes his seed into her and conceives the child Horus.68 Plutarch's source for the story of her embrace of the dead body of Osiris likely included this idea of Isis conceiving Horus through copulation with the erect phallus of the dead Osiris (Plutarch may have excluded this detail because he deemed it lacked dignity).

The story of the conception of Horus is found in several Egyptian texts. In one hymn to Osiris, we read:

Thy sister Isis acted as protectress of thee. She drove away thine enemies, she averted seasons [of calamity], she recited formulae with the magic power of her mouth. . . . She went about seeking him untiringly. She flew round and round over the earth uttering wailing cries of grief and she did not alight on the ground until she had found him. She made light appear from her feathers; she made air to come into being by her two wings, and she cried out the death cries for her brother. She made to rise the helpless members of him whose heart was at rest, she drew from him his essence and she made therefrom an heir. She suckled the child in solitariness, and none knew where his place was, and he grew in strength and his arm increased in strength in the House of Keb [Geb, earth].69

FIGURE 15

Osiris begetting Horus by Isis, who, in the form of a hawk, hovers over Osiris's raised penis. The second hawk is Nephthys. At the head of the bier sits Hathor, and at the foot sits the frog-Goddess Heqet. Drawing from sarcophagus art. (From Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge, Osiris: The Egyptian Religion of Resurrection [New Hyde Park, NY: University Books, 1961])

Another text tells the story of Horus's birth in the papyrus swamp of the delta near the city of Buto. Here, the pregnant Isis flees from where Seth has imprisoned her, giving birth and hiding the child in the papyrus swamp (fig. 16). One day, while obtaining food, she returns to find the child dead of a scorpion sting. Isis utters loud lamentations, and her sister Nephthys comes to her aid, appealing to the God Thoth, who gives Isis magic incantations to draw out the poison and revive the child.70

In Plutarch's story, Isis hides the chest with the body of Osiris in the swamp, where it was found by Typhon (Seth). He cuts the body into fourteen parts and scatters them. Isis then embarks on a second search, now for the scattered parts of Osiris's body. Sailing through the marshes in a papyrus boat, she finds all the parts of the body except the phallus, which has been swallowed by a fish. Isis fashions a likeness of the phallus and “consecrates” it, “in honor of which the Egyptians even today hold festival.” No Egyptian text has this idea that the phallus of Osiris was lost and a likeness fashioned by Isis. Plutarch does not say that Isis impregnated herself with Osiris's phallus in order to conceive the child Horus. Rather, he details how the many shrines to Osiris throughout Egypt are depicted as places where Isis buried different parts of his body.71

FIGURE 16

The birth of Horus in the papyrus swamps. (From Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge, Osiris: The Egyptian Religion of Resurrection [New Hyde Park, NY: University Books, 1961])

The young Horus is nurtured by Isis and then trained by his father, Osiris, from the land of the dead to become a powerful warrior. Horus avenges Osiris by doing battle with their enemy Seth in order to vindicate his right to inherit the throne of the Two Lands of Egypt.72 References to the conflict of Seth and Horus are found in various texts. One rather bawdy version from the twentieth dynasty (twelfth century BCE) has the two adversaries contending over a prolonged period. Isis continually intervenes on her son's behalf, until Seth refuses to take part in the contest while Isis is present. Seth and Horus withdraw to an island. Seth charges the ferryman not to transport any woman resembling Isis. But Isis bribes the ferryman and makes her way there, tricking Seth into validating the claims of Horus.

The gods award the office to Horus, but Seth challenges him to an ordeal in which both become hippopotamuses, with the award going to the one who stays under water the longest. Isis harpoons Seth, but she withdraws the harpoon when Seth appeals to her as his sister. Horus is enraged at Isis and cuts off her head (which is restored by giving her a cow's head). Seth takes out Horus's eyes and buries them in the earth, but his sight is restored by Hathor (the cow Goddess with whom Isis has been identified). Seth and Horus then engage in a contest with rival ships, trying to sink each other's vessel.

Finally, the gods appeal to the judgment of Osiris, who emphatically demands that Horus be given the throne, as the son of the one who gave grain to the gods. Eventually, Seth concedes to Horus the right to rule as the son of Isis and Osiris. Seth is also granted his own sphere of rule in the heavens, as the thunder God.

Then Horus, the son of Isis, was brought, and the white crown set upon his head. And he was put in the place of his father Osiris. And it was said of him: You are the good king of Egypt; you are the good Lord—life, prosperity, health—of every land up to eternity and forever. Then Isis gave a great cry to her son Horus, saying, “You are the good king! My heart rejoices that you light up the earth with your color.”73

The central role of Isis in promoting Horus as king and heir of Osiris is supplemented by another story of her guile on behalf of her son. Two texts from the nineteenth dynasty (1350–1200 BCE) tell how Isis was able to obtain the secret name of the supreme God Re. In this text, Isis is described as “a clever woman. Her heart was craftier than a million men; she was choicer than a million gods; she was more discerning than a million of the noble dead. There is nothing which she did not know in heaven and earth, like Re, who made the content of the earth.” To complete her knowledge, “the goddess purposed in heart to learn the name of the august god.”74

Isis gathers spittle dropped from the God's mouth and kneads it with earth, fashioning a poisonous snake that bites the God on his daily stroll. When the God's suffering grows unbearable, Isis offers to heal him but only if he tells her his secret name. Finally, Re agrees to impart this name to her but only if she then shares this knowledge with Horus, vowing him to secrecy. Re tells her to incline her ears and draw the name from his body into her body. Isis revives Re, while drawing from him his highest power, with which she endows her son, Horus. The text ends with the jubilant cry, “The poison is dead, through the speech of Isis, the Great, the Mistress of the gods, who knows Re by his [own] name.”75

Isis, like Inanna and Anat, is a “kingmaker” who sets the royal heir on the throne. She does so as lover and faithful wife of the dead king and as devoted mother of the new king, her son. Her instruments of power are not military vigor, but magic powers guilefully employed. Using these, she resurrects Osiris, heals Horus and Re, and learns the deepest secrets of the universe, which she passes on to her child, conceived through her power to revive the phallus of the dead Osiris. Horus, suckled at her breast, is enthroned on her lap, the seat of power. These evocative symbols make dramatically clear the ancient Near Eastern supposition that while men rule as kings and lords, it is the power of goddesses that puts them on their thrones.

DEMETER AND PERSEPHONE OF GREECE

The Demeter-Persephone myth and cult in Greece are unique because they privilege the mother-daughter bond rather than the relation of young goddess and king, as in the Inanna and Anat stories, or the royal family triad of husband, wife, and male child, as in the Egyptian story. (None of these stories feature a Mother Goddess and son-lover.)76 The story of Demeter and Persephone is dramatically told in a late seventh-century BCE text that probably reflects the official story of the Eleusinian mysteries.77

The story opens with the rape of Persephone. A beautiful young girl, she is playing and gathering flowers with the daughters of Oceanus. She reaches for the narcissus flower, and the earth opens. Pluto in his horse-drawn chariot rises from below, seizes her, and carries her off to his underground realm. Persephone continually cries out, but her laments at first are heard only by Hecate and Helios, the sun God. Eventually, however, her mother, Demeter, also hears them. Demeter speeds across the earth with flaming torches, seeking her daughter. On the tenth day, she is met by Hecate, who tells her that she too heard the cries. They go to Helios, who reveals that Persephone has been taken to be the bride of Pluto, a union sanctioned by Zeus himself, father of Persephone. Helios advises Demeter to accept this as a fait accompli.

Demeter refuses to do so and becomes more savagely angry. She will not attend the assemblies of the gods in Olympus and instead disguises herself as an old woman. Wandering through towns and fields, she eventually comes to Eleusis, where she sits down at the maidens' well. There, she is met by the four daughters of Celeus, lord of Eleusis. She offers herself for hire as a housekeeper and is taken into this household to nurse the late-born son of the king. Demeter, who has been fasting, refuses wine offered by the matron of the house, Metaneira, but breaks her fast with a barley drink. A woman servant, Iambe, cheers her up with ribald jests.

The disguised Demeter not only nurses the child but also seeks to give him immortality by dipping him in fire by night. Metaneira spies on her one night and screams when she sees Demeter putting her child in the fire. Demeter is enraged, throws the child on the ground, and castigates the mother for her stupidity. She then reveals her divine nature and demands that a temple be built. King Celeus calls the people together, and they build the temple. Demeter withdraws into it and calls down a blight on the land, causing no seeds to grow. In this way, she seeks to punish the Olympian gods for their connivance in the rape of her daughter, by denying them the sacrifices that would be brought to them by humans (and thereby destroying human life as well).

FIGURE 17

Demeter and Kore (Persephone), early fifth century BCE. Marble bas-relief. (Louvre, Paris; photo: Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY)

Zeus seeks to mollify Demeter by sending Iris to summon her to Olympus. When the summons is refused, he sends one god after another, but their entreaties are rejected. Demeter declares that no seed will spring from the ground until her daughter is restored to her. Finally, Zeus agrees to release Persephone and sends Hermes to fetch her. But Pluto secretly inserts pomegranate seeds in her mouth as she is departing, forcing her to taste them. In a touching scene, Demeter and Persephone are reunited, rushing into each other's arms (fig. 17). But Demeter immediately senses that something is wrong and asks her daughter if she has tasted food in the underworld. Persephone confesses that Pluto forced her to do so.

Zeus sends their mother, Rhea, to Demeter to propose a compromise. Persephone will spend a third of the year in the underworld as Pluto's wife, but for the other eight months she will live with her mother and the Olympian gods. Demeter accepts this proposal and lifts the blight on the earth, restoring its fertility. She then goes to the leaders of the Eleusinians, among them Triptolemus and Eumolpus, and teaches them how to conduct her rites. Those who are initiated into them are assured of a happy life in the hereafter: “Happy is one among humans on earth who have seen these mysteries; but the one who is uninitiate and who has no part in them, never has a lot of like good things once he is dead, down in the darkness and gloom.”78

This text is foundational for the Eleusinian mysteries, which were probably celebrated as local rites as far back as the Bronze Age (c. 1500 BCE). They became an all-Greek festival in the sixth century BCE and were gradually opened to the larger Greco-Roman world. The precinct where they were celebrated was continually enlarged into the second century CE, and the rites persisted there into the fifth century, when they were closed down by barbarian raids and Christian hostility.79

The story reflects key aspects of the rites. Triptolemus, referred to in the story, was said to have been given the knowledge of grain cultivation by Demeter, which he then carried throughout the world. The Eumolpids were a priestly family of Eleusis who held the leading offices of Hierophant (chief priest) and two assistant priestesses from the time the mysteries were founded into the last days of these rites in the late Roman period.80 The rites were celebrated in late September and early October over a nine-day period. They were open to all Greek-speakers, men and women, even slaves, if they were innocent of shedding blood.

The rites began in Athens, with the fasting initiates purifying themselves in the sea, followed by a sacrifice of suckling pigs. Then there was a procession to Eleusis, followed by a torchlight enactment of the sorrowful search of Demeter for her daughter and their joyful reunion. The fast of the initiates was broken by drinking the barley drink. A dramatic exposure of holy objects followed; initiates were sworn to strict secrecy about these parts of the ritual. The initiates then departed for their homes, assured that their experiences would fortify them for a better life in the world to come.81

Lesser rites honoring Demeter were also conducted in different Greek cities. One, which took place over three days, was the Thesmophoria, a festival open only to women. On the first day, pigs were sacrificed in an underground chamber, and the decayed remains of the previous year's sacrifice were brought up and made available to farmers to fertilize their fields. On the second day, the women sat on the ground imitating the deep mourning of Demeter for her daughter. On the third day, this mourning was transformed into celebration with a banquet.82 This rite seems linked primarily with agricultural fertility, but perhaps also with hopes for “good birth” for the women involved in the ritual.83 The exclusion of men marked it as a rite for women to bond with one another in their shared experiences of loss and hope.

In the strictly gender-segregated society of classical Greece, the Demeter-Persephone story must have held deep meaning for women, especially the matrons who led the Thesmophoria rites. The special bond of mother and daughter in the women's part of the segregated household must have often been rudely broken by a powerful father who snatched away a beloved daughter into a marriage with one of his older male companions, with little consultation with the mother or daughter. Mothers and daughters must have experienced this as rape, when daughters, usually in their early teens, were carried off wailing into an unknown life. The return of such a daughter to visit her mother must also have reenacted something of the joy found in the Demeter story.

Demeter in some ways is Greek woman writ large. As corn Goddess, she gives the gift of grain and the land's fertility. Her gift of weaving provides the cloth that clothes society. But she is also subject to rape, to arbitrary male violence. Demeter herself was said to have been raped by Zeus and also by Poseidon.84 She responds to the rape of her daughter by withholding the gift of fertility. Before this power, even the Olympian gods stand helpless. So, too, were women in Greek society deeply vulnerable to male power, but they had as their weapon of last resort the withholding of their sexuality and fertility. Tradition credits women with stopping the fratricidal Peloponnesian Wars by withholding sex from men.85

The ancient Greek world did not see the tale of Demeter as only a woman's story. It was a drama assumed to appeal to all, one that allowed men and women to experience sorrow, loss, and joyful reunion of mother and child. It also carried with it two profound reassurances, symbolically linked: the return of springtime fertility after a season of earth's barrenness; and the hope that, in the terrifying journey from this life to the next, one would find kindly gods in the world below. Thus, we find in both the Isis and the Demeter myths and cults keynotes that would become increasingly central to ancient religion. Agricultural plenty and political stability were important but insufficient. Immortal life had been deemed unavailable to mortals in Babylonian and Canaanite cultures, but this hope for immortality became central in Greco-Roman piety. Hope for life after death increasingly supplanted the hopes for renewal of agricultural life central to earlier Mediterranean religion.