SEVEN • Tonantzin-Guadalupe

The Meeting of Aztec and Christian Female Symbols in Mexico

In 1492, the expansion of western European powers began with the voyage of Cristobal Colón, whose last name suggests the word “colonialism” (from colonia). The first wave of Western colonialism came from Catholic Spain and Portugal. Both countries saw the task of converting the natives to Christianity as integral to their self-justification for conquering hitherto unknown peoples and lands. The Spanish conquered in the name of Christ and the king of Spain, as a nation that saw itself chosen by God to counteract infidels and spread the true faith. They also carried with them the veneration of the Virgin Mary, in many local Spanish expressions, and planted these in the New World.

This chapter examines the violent meeting between an aggressive Catholic Christianity with strong Marian devotion and indigenous Mesoamerican cultures with highly developed religious systems that paired male and female divinities. The Spanish construed indigenous religion as “idolatry” and indigenous gods as “demons,” expressions of the devil. They set themselves the task of wiping out all traces of native religion and replacing it with Spanish Catholicism. To this end, they demolished all the temples they found, destroyed images, and burned the codices that enshrined local wisdom. They also effected a near-genocide of the indigenous people, reducing the population of Mesoamerica from an estimated twenty-five million in 1519 to one million by 1592, partly through warfare and exploitation of labor and partly through the inadvertent transmission of diseases from Europe to which indigenous peoples lacked immunity.1

Ironically, the first Spanish missionaries, particularly the Franciscans, are also a main source for what we know of native religion, society, and culture. A small number of Franciscans believed that in order to evangelize the Nahuatl peoples of Mesoamerica, they must learn their language and strive to understand and carefully record their culture. Only in this way could they communicate the true faith effectively and free the “Indios” from their idolatry. The Franciscans did not intend to create a syncretism between Christianity and the religions of the Nahuas, but they nevertheless helped to do so by creating a linguistic and cultural bridge over which the Nahuas could cross into Christianity while preserving much of their own worldview under the surface. In the process, the Franciscans left us major ethnographic studies of Nahuatl culture and society, such as Andres de Olmos's (1491–1570) Codex Tudela and Bernadino de Sahagún's (1499–1590) twelve-volume Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España (General History of the Things of New Spain).2

That modern study of Nahua and Mexica (Aztec) religions relies on documents created for the purpose of eliminating these religions raises serious problems. Can we really free the content of these documents from their interpretive bias and accurately hear the voices of the indigenous culture? Generally, scholars of Nahuatl culture argue that we have no choice but to use these documents. Moreover, the Franciscan methodology of training indigenous youth to be trilingual (Nahuatl, Spanish, and Latin) and then using these literate youth as go-betweens to interview the elders of Nahuatl culture about their traditions has provided us with invaluable source material. By considering this material in combination with surviving pre-conquest codices, archaeological studies of preconquest sites, and anthropological study of contemporary Nahuatl people, most scholars believe that a reasonably accurate picture of preconquest culture can emerge.3

This chapter presents a brief sketch of female divinities among the Mexicas shortly before and after the Spanish conquest. It then examines the current state of knowledge about the emergence of the veneration of the Virgin of Guadalupe at the hill of Tepeyac, near Mexico City. I also attempt to evaluate the extent to which this veneration of Guadalupe represents a syncretism of the Catholic Mary and a pre-Columbian veneration of a Mother Goddess, Tonantzin. In the context of this book, this chapter provides a case study of how the Catholic veneration of Mary, with its own roots in ancient Near Eastern goddess worship, was and continues to be a vehicle for the assimilation of goddess worship into Christianity from the conquest period to today.

NAHUA VIEWS OF FEMALE DEITY

The Aztecs built their understanding of the divine on many layers of earlier Mesoamerican culture. Given the nature of the sources, tracing these different stages of development is too difficult to be attempted here. Suffice it to say that the views of the divine found in the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century codices and documents represent a long process of cultural growth going back thousands of years to classical and preclassical Mesoamerican village and urban cultures.4 The developed Aztec understanding of the gods reflects a view of a sacred cosmos with many levels. At the deepest level, unmanifest divinity is seen as existing in the ultimate, or thirteenth, heaven. This divinity underlies all life but never appears in human affairs. Rather, it is manifest in a multiplicity of deities that come forth from this ultimate divinity and in turn generate and are present in the visible cosmos.

This ultimate divinity is understood as both unitary and dual, male and female: Ometéotl, the giver of life, or master of duality, whose dual male-female nature is represented by the pair Ometecuhtli and Omecíhuatl, the lord and lady of duality. The following outline by Miguel León-Portilla illustrates the observation of the sixteenth-century Spanish Franciscan chronicler Juan de Torquemada “that these Indians wanted the Divine Nature shared by two gods, man and wife.”

Ometecuhtli-Omecíhuatl, the Lord and Lady of Duality

Tonacatecuhtli-Tonacacíhuatl, the Lord and Lady of our maintenance,

In teteuinan, in teteu ita, Huehuetéotl,

the mother and father of the gods, the old god.

Xiuhtecuhtli is at the same time the god of fire,

who dwells in the navel of fire, tle-xic-co

Tezcatlanextía-Tezcatlipoca, the mirror of day and night,

Citlallatónac-Citlalinicue, the star that illumines all things,

the lady of the shining shirt of stars,

In Tonan, In Tota, our mother, our father,

Above all, he is Ometéotl, who dwells in the place of duality, Omeyocan.5

This unity in duality allows all the plurality and contradictory forces of the universe to emerge from the primary source of life and to be held together as an ultimate unity. In Nahua mythology, a dual male-female deity emerges from Ometéotl, who rules over the visible world. The pair is made up of Tezcatlipoca (smoking mirror), who represents night, and his female counterpart, Tezcatlanextía (illuminating mirror), who represents day.6 This female aspect of Tezcatlipoca exists side by side with the fourfold expressions of Tezcatlipoca, the four sons of the primal parents, who represent the four directions of the horizontal spatial world. These four directions are signified by the four colors of Tezcatlipoca—red, white, blue, and black. Quetzalcóatl, a beneficent deity that created humans and provided them with corn, is identified as one of these sons, while the Aztecs identified the blue Tezcatlipoca with their warrior God Huitzilopochtli.7

Tezcatlipoca, the “Lord of the Near, the Close” (tloque nahuaque), came to be seen as the primary sovereign deity of the universe. He is all-powerful but also arbitrary and capricious, even sinister, subjugating humans to a power they cannot control or count on as beneficent and to whom they can only plead for favor. In words recorded by the Franciscan Andres de Olmos, “Tezcatlipoca was everywhere and knew the hearts and minds of others, so they called him Moyocoya, or the all powerful and unequaled.”8 Prayers addressed to Tezcatlipoca often include an address to “our mother, our father,” such as the following dedication of a child to the priesthood shortly after birth:

Our Lord, Lord of the Near and the Close, [this child] is your property, he is your venerable child. We place him under your power, your protection with other venerable children, because you will teach him, educate him, because you will make eagles, make ocelots of them [the two orders of Aztec warriors], because you educate him for our mother, our father, Tlaltecuhtli, Tonatiuh [the earth Goddess and the God of the fifth sun of the present era].9

This male-female duality of the Nahua cosmic system does not seem to be a hierarchy of value. Maleness does not represent a superior principle and femaleness an inferior principle, as they did in the Greek dualistic hierarchy of spirit and matter. Aztec society was strongly gender differentiated and socially stratified, with male elites dominating the powerful public military, priestly, and political roles, while women were located primarily in the domestic sphere. But women's work roles of food preparation and weaving, as well as their participation in public areas such as marketing, medicine, and priestly functions, were vital for both family and corporate life.10 Gender differentiation does not seem to have been abstracted as a moral or ontological hierarchy.11 Nor does cosmic gender duality appear to have been organized in terms of complementary opposites, such as light-darkness and active-passive, although one leading scholar of Nahua culture has construed it in this mold.12

Rather, male-female dualism appears to operate more as a dynamic parallelism that pervades the cosmic system. The Aztecs conceived of the cosmos as spatially organized into thirteen upper heavens and nine levels of the underworld, with the surface of the earth lying between the two. There are male and female deities at every level of this cosmos. Just as the ultimate deity of the thirteenth heaven is a male-female duality, so the deepest (ninth) level of the underworld is ruled by a male-female pair, Miclantecuhtli and Mictecihuatl, the lord and lady of Mictlan, the underworld where ordinary people went when they died. Male and female deities also represent fertility, rain, fire, and other such cosmic forces.

Many deities are described as androgynous or coupled. The old deity of fire, Huehuetéotl, for example, is sometimes seen as androgynous and sometimes as linked to the Goddess Teteo Innan, “mother of the gods,” or Toci, “our grandmother.” Sahagún speaks of this Goddess as strongly related to healing:

She is the mother of the gods. Her devotees were physicians, leeches, those who cured sickness of the intestines, those who purged people, eye-doctors. Also women, midwives, those who brought about abortions, who read the future, who cast auguries by looking upon water or by casting grains of corn, who read fortunes by use of knotted cords, who cured sickness by removing stones or obsidian knives from the body, who removed worms from the teeth, who removed worms from the eyes. Likewise the owners of sweat-houses prayed to her; wherefore they caused her image to be placed in front of the sweat-house. They called her the “grandmother of the baths.”13

The main festival dedicated to Toci or Teteo Innan was the harvest festival of Ochpaniztli, which celebrated both the gathering of the harvest and the return of the dead stalks to the earth for the renewal of life in the spring. For this festival, a woman was chosen to represent Toci. She was garbed, named, and treated with greatest honor and veneration as the Goddess. She danced and rejoiced “so all could see her and worship her as a divinity.” At the culmination of this time of veneration, she was sacrificed and the skin removed from her body. The skin was donned by a man, who was then venerated as the Goddess. In this way, the role of the Goddess was taken primarily by a female and then secondarily by a male. Finally, the skin was placed on a straw figure to represent the final incarnation of the Goddess into the maize stalks. Each transformation represents a stage in the cycle of the ripened corn turned into the human being and then back to the earth.14

Women played key roles in the priesthood. A girl baby destined for the priesthood was dedicated at birth. At fifteen, she was taken to be trained as a woman priest, or cihuatlamacazqui. Women priests remained celibate during their time of service but could later marry. The Ochpaniztli festival, dedicated to the Mother Goddess Toci, was directed by a woman priest with a woman assistant, a “white woman” (painted white) responsible for the decorations, the preparation of the ritual, the sweeping of the site, and the lighting and extinguishing of the ritual fires. Women priests were specially garbed and led ecstatic dancing during rituals. “When they danced, they unbound their hair, their hair just covered each one of them like a garment.”15

During the maize festival of Quecholli, young priestesses dedicated to the Goddess of corn carried seven ears of corn wrapped in cloth in a procession. They wore feathers on their arms and legs, and their faces were painted to represent the Goddess. They sang and tossed handfuls of corn of different colors and pumpkin seeds to the crowds that lined the processional way. The people scrambled to gather up the corn kernels and seeds as a token of the good harvest of the coming year.16

Other deities, such as Xochipilli, lord and lady of flowers and festivals, and Tlaltecuhtli, the earth serpent, are also androgynous, although primarily seen as female. Gods and goddesses are often portrayed as couples, such as Tlaloc, the God of rain that waters the earth, and Chalchiuhlicue, associated with underground springs and waters. The Tlalocs are also seen as plural, and Chalchiuhlicue is called their “older sister.”17 Quetzalcóatl, the plumed serpent, is himself dual, combining bird and reptile. He is paired with various goddesses—Tonantzin (our precious mother), Cihuacóatl (female serpent), Yaocihuatl (warrior woman), and Coatlicue (serpent skirt).18 Some of these male and female deities probably existed independently, and priestly thinkers have sought to systematize them into pairs. But the pairing often shifts, and the goddesses remain definite personalities in their own right.

One interesting Goddess is Tlazolteotl, “the filth eater.” She is described by Sahagún's informants as both condoning and purging debauchery and moral evils of all kinds: “One placed before her all vanities, one told, one spread before her all [one's] unclean works—however ugly, however grave, avoiding nothing because of shame. One exposed all before her [and] made one's confession in her presence.” For Sahagún, such a dual role was morally incomprehensible; but for the Aztecs, ordure and other wastes were both the symbols of debauchery and also recycled fertilizer, so it was comprehensible to see the Goddess of “filth” as also purging it.19 Sahagún goes on to quote a penitential prayer to this Goddess and to all the gods: “Mother of the gods, father of the gods, old god, here hath come a man of low estate. He cometh here weeping and anguished. Perhaps he has sinned, perhaps he has erred, perhaps he has lived in filth. He cometh heavyhearted; he is sorrowful. Master, our Lord, protector of all, also take away, pacify, the torment of this man.”20

Central to Aztec cosmology and culture is a sense of a dynamic twoness or plurality that interacts along various axes to sustain life. In the sacred center of the capital city of Tenochtitlán, the great pyramid is unified at the base and separates into two, one dedicated to the sun and war God, Huitzilopochtli, and the other to the God of rain and fertility, Tlaloc. Authority in the Aztec state was also dual, represented by the Tlatoani, or speaker, and Cihuacóatl, the Mother Goddess, both roles taken by males.21 The two elite warrior groups whose compounds are on either side of the great temple are identified as jaguars (ocelots) and eagles, thus pairing two powerful land and sky animals. The human body itself combines the energies of the head, identified with the sun and the destiny of the individual (controlled by the calendar); the heart, linked to divine fire; and the liver, linked to breath and health. The body is literally the meeting place of these many cosmic forces.22

Aztec rhetoric, or elegant language, typically takes the form of a double phrasing, describing everything in two ways that are parallel and mutually reinforcing. Only by looking in two different ways does one hit at the deeper meaning that connects the two descriptions. Thus, for example, in an address to a newly born girl child, the father says to her: “Here you are, my little daughter, my precious necklace, my precious quetzal feather, my human creation, my offspring. You are my blood, my color, in you is my image. Now grasp, listen; you were born, sent to earth by our Lord, Possessor of the Near and the Close, maker of humankind, creator of people.”23

Although rooted in ultimate oneness in duality, the manifest universe is seen as ephemeral, besieged by conflicting forces that tend toward collapse and destruction, and maintained only by self-sacrificing efforts on the part of gods and humans. The Aztecs told the story of cosmic history as a succession of four “suns,” or ages, each of which was eventually destroyed and swept away. The first age, or sun, began three thousand years ago. The gods battled for ascendancy, with Tezcatlipoca predominating. This age was populated by acorn-eating giants, who were finally devoured by jaguars. Quetzalcóatl presided over the second sun, which was populated by piñon nut eaters and ended with a devastating hurricane that transformed the survivors into monkeys. The third sun was associated with Tlaloc, inhabited by aquatic seed eaters, and destroyed by a fiery rain that transformed the survivors into dogs, turkeys, and butterflies. Chalchiuhtlicue, Goddess of waters, presided over the fourth sun, which was populated by wild seed eaters. They were victims of a great flood, and the survivors were turned into fish. At the end of each age, the sun was destroyed, and the world plunged into darkness.24

After the end of the fourth sun, the gods gathered at Teotihuacán (the great sacred city of the classical era, 200–800 CE, which was in ruins when the Aztecs arrived in the Valley of Mexico). There, the gods sacrificed themselves to create the fifth sun. They kindled a great fire and invited the brave young warrior God Tecuciztecatli to sacrifice himself by hurling his body into the fire. He tried four times but drew back each time in fear. Finally, an old, sickly God, Nanahuatzin, threw himself into the flames and was transformed into the sun. Then Tecuciztecatli gained courage and also jumped into the flames, becoming a second sun. In order to avoid having two equal suns, the gods threw a rabbit at the second sun, darkening it to become the moon.

But when the sun rose in the east, it did not move but “swayed from side to side.” All the gods then decided to sacrifice themselves in order to empower the sun to move through the sky. But even then the sun did not move, until one remaining God, Ehecatl, the wind God, “exerted himself fiercely and violently as he blew,” setting the sun moving in an orderly way across the sky.25 But this sun too will eventually fail and be destroyed. “As the elders continue to say, under this sun there will be earthquakes and hunger and then our end will come.”26 Thus, the Aztecs lived with a pessimistic worldview, in which joys were fleeting and eventual destruction sure, staved off only by tremendous effort.

Just as the gods sacrificed themselves to create and empower this sun, so humans must sacrifice, both by bleeding themselves and by sacrificing the flower of their men and women to feed the sun in its threatened daily course. This worldview was the foundation of the Aztec sacrificial system. The elites, kings, and priests—and at times the whole community—pierced their bodies with thorns to offer their blood. They sacrificed the elite of warriors taken in battle, and also women and children, to offer their blood to sustain the energies of the sun and the earth. Those sacrificed, the heroes who died in battle and the women who died in childbirth, became gods and went to the house of the sun, where they accompanied and aided the sun in its daily course across the sky.

After the fifth sun was secured, the land surface of the earth and its vegetation were created by Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcóatl by bringing the Goddess of earth from the heavens. The Goddess floated down on the existing waters. The two Gods changed themselves into huge snakes and took hold of the two ends of the Goddess and broke her in half. They made the earth from her front half and took the other half back to the heavens. But the Goddess was angry, and the other gods consoled her, ordering that all the fruits necessary for the life of humans would be made from her. They made from her hair the trees, flowers, and grasses; from her skin, the fine grass and flowers; from her eyes, the wells and springs; from her mouth, the great rivers and caverns; from her nose, the valleys; and from her shoulders, the mountains. But the Goddess continued to weep and would not be quiet or bear fruit until she was watered with the blood of humans.27 Again, the sacrifice of the gods must be compensated by humans sacrificing themselves.

Two other important stories are told of Quetzalcóatl, the wise, beneficent God, as creator of humans and giver of corn, the food that sustains humans of the present sun. Quetzalcóatl went to the region of the dead, appearing before the lord and lady of Mictlan, to fetch the bones of those who died, in order to create from them a new generation of humans. But, before he would release the bones, the lord of Mictlan set Quetzalcóatl the seemingly impossible task of blowing on a conch shell with no holes. With the aid of worms that made holes and bees and hornets that filled the shell, Quetzalcóatl accomplished this task. But when he tried to leave with the bundle of bones, he fell down into a pit, scattering the bones, which were nibbled by quail. When he revived, Quetzalcóatl gathered what was left of the bones and took them to the paradisal realm of Tamoanchán. There, he gave them to the Goddess Cihuacóatl, who ground them in her jade bowl. Quetzalcóatl then bled his penis over the bones, and, from this combination of ground bones of the dead and divine blood, the new race of humans was made.28

Then, to provide food for the humans, Quetzalcóatl changed himself into an ant and followed a red ant into a mountain where corn was stored. He carried it to Tamoanchán, where he gave it to the first human pair, Oxomoco and Cipactónal. There, the gods ate of the corn and “fed it to us to nourish and strengthen us.”29 Corn was the basis of human nourishment, and humans themselves were seen as “corn-beings.” This view that corn and human flesh were the same substance seems to be reflected in the Aztec practice of eating small pieces of the flesh of sacrificed victims, which were placed on the corn stew in a ritual meal in the homes of those who contributed the sacrificed captive.30 In effect, corn and human flesh were seen as “consubstantial.”

Significantly, the human counterpart of the God Quetzalcóatl, the wise priest-king of Tollan, was remembered as opposing human sacrifice. He practiced self-bleeding for his people and called only for the sacrifice of flowers and butterflies in the temple. But he was defeated by a number of tricks perpetrated by the sorcerer Titlacauan. In another version, this sorcerer was Tezcatlipoca, who revealed Quetzalcóatl's vulnerability to him by showing him his old age in a mirror and seducing him into drunkenness and sexual impropriety. This caused Quetzalcóatl to flee his city in shame, and it fell into ruins. In one version, he fashioned a raft and set forth into the sea to the east. In another, he sacrificed himself on the shore of the sea and was transformed into the morning star.31 Quetzalcóatl and his city of Tollan were remembered as the prototypes of the ideal city and ruler, but they were seen as too idealistic and so bound to fail.32

Yet it was believed that Quetzalcóatl would return, as a white-skinned bearded man coming from the eastern sea (the Atlantic). Ironically, the demise of the Aztecs was partly a result of their willingness to entertain the belief that the Spanish conqueror Hernán Cortés, who arrived in ships in 1519, might be Quetzalcóatl returned. By a striking coincidence, Cortés landed on the very day of I Reed (a year in the Aztec calendar of fifty-two-year cycles) when it was believed that Quetzalcóatl had departed and would return.33

The Aztecs also had stories specific to their own group, depicting themselves as a people destined for empire. They told of their migration from their original place of origin—a “white place,” Aztlan, in the north—as poor and despised people and their arrival in the Valley of Mexico. They battled with other established groups in the region and were banished to the swampy region of the lakes. There, they saw the prophetic sign of the eagle perched on a cactus eating a snake (the image on today's flag of Mexico) that signaled the place where they were to build their great city.

Two Aztec origin stories strikingly feature conflict with rival sisters of the warrior God Huitzilopochtli. One has to do with the birth of Huitzilopochtli. His mother, the earth Goddess Coatlicue (fig. 41), was doing penance by sweeping in a temple on the mountain of the serpent, Coatepec, when a ball of feathers fell down on her. Placing these in her bosom, she became pregnant. Her daughter, Coyolxauhqui, became enraged at what she saw as her mother's disgrace and summoned her four hundred brothers, the gods of the south, to come and kill their mother. But one of the brothers warned the mother of the coming assault. When Coyolxauhqui led her brothers up the hill, Huitzilopochtli was born fully armed and struck his sister, cutting off her head and sending her body rolling down the hill to break in pieces.34

In 1978, workers in Mexico City discovered a huge circular stone in the area of the plaza behind the national cathedral, which is built on the Aztec sacred temple precinct. The stone carried a carving of the dismembered body of Coyolxauhqui, dressed in the feathered helmet and arm and leg armor of a warrior but with bare torso. This area has since been excavated, and it has become evident that this image of the shattered body of Coyolxauhqui once lay at the foot of the great temple of Huitzilopochtli. At the top of the temple, victims were sacrificed, their chests split open and their hearts offered to the gods to sustain the sun, while their bodies were sent tumbling down the stairs to land in the area of the dismembered body of the conquered sister. In effect, the temple itself represented the serpent hill, Coatepec, and each sacrifice reenacted the defeat of the enemy sister (fig. 42).35

FIGURE 41

The Aztec Earth Goddess Coatlicue, fifteenth or sixteenth century. (Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico City; photo: Werner Forman / Art Resource, NY)

The second story took place in the migration period. On their way to discovering the place of their capital, Tenochtitlán, Huitzilopochtli abandoned his Goddess sister Malinalxoch, described as an evil sorceress, while she was sleeping. When she woke up and found herself abandoned by her brother, Malinalxoch led her followers to the mountain Texcaltepetl, where they established themselves. She bore a child named Copil to the king of Malinalco and thus became the founder of a rival city-state.36

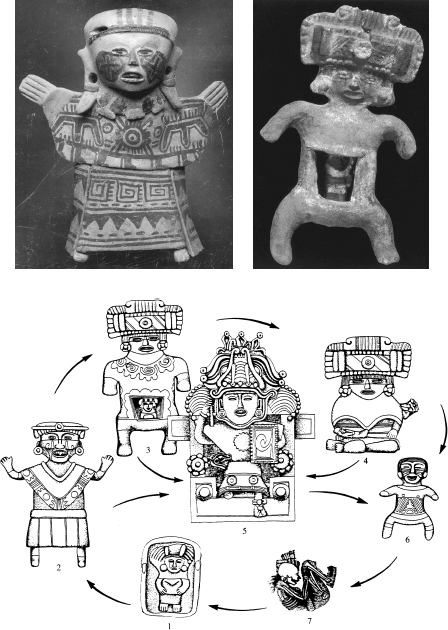

What do these stories of the conquered or abandoned divine sister mean for Aztec gender relations? On one level, the story of the defeat of Coyolxauhqui and the four hundred brothers is a cosmological story of the daily defeat of the stars by the rising sun. But it also seems to reflect wars with rival cities that the Aztecs subdued to build an empire in Mesoamerica. Some of these cities may have had powerful female rulers, but it may also be that the Aztecs represented conquered cities as rival, conquered sisters.37 Recent excavation of the temple center at Xochitecatl, a sacred site that flourished between 650 and 850 CE, resulted in the discovery of a large group of figurines, mostly female. The figurines express the female life cycle, from pregnant women and women with children in their arms and babies in cradles, to young women orantes and priestesses, to elderly women. At the center of this group of females is the stunning figure of a priestess warrior seated on a throne or palanquin, wearing a helmet and holding a scepter and shield of her office as governor (fig. 43).38

FIGURE 42

The dismembered Goddess Coyolxauhqui, fifteenth or sixteenth century. (Museo del Templo Mayor, Mexico City; from Esther Pasztory, Aztec Art, published by Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York; all rights reserved)

The story of Quetzalcóatl speaks of such a female priestess-ruler: “The Lady Xiuhtlacuiloxochitzin was installed as Speaker. Her grass dwelling stood at the side of the market plaza where Tepextitenco is today. The city of Cuauhtitlán passed to her since she was the wife of Huactli, it is said, and because she spoke often to the [sic] devil Itzpapalotl” (the Goddess Obsidian Butterfly—in keeping with the Spaniards' demonization of Aztec deities, the Spanish chronicler calls her a devil).39 Perhaps when the Aztecs arrived in the region, there were some powerful women rulers of cities who opposed their rise to power, and the defeat of the priestess-warrior sisters symbolized the subjugation of these rival peoples.

FIGURE 43

From top left, clockwise: Praying woman figurine, temple of Xochitecatl; pregnant woman figurine, temple of Xochitecatl; group of women figurines expressing the life cycle, twelfth century, pyramid of Xochitecatl. (From Arqueología Mexicana 5, no. 29 [January–February 1998])

THE NAHUAS AFTER THE CONQUEST AND THE EMERGENCE OF THE CULT OF GUADALUPE

The history of Spanish-native relations in sixteenth-century Mexico has been portrayed as complete devastation of the indigenous peoples. Their ceremonial sites were destroyed, their codices burned; nearly 90 percent died from disease. The Spanish appeared to have wiped out native culture, creating a blank slate on which they imposed Spanish Catholicism and an administrative system controlled from Spain. Insofar as native culture survived, most believed, it did so in isolated pockets removed from Spanish control. But this picture is misleading. In fact, recent study of documents of daily life written in Nahuatl by Nahua peoples themselves, in the alphabetic script devised by the friars, reveals a different picture. Although Aztec power was destroyed and replaced by the Spanish central authority, many of the deeper structures of Nahua social organization and culture continued, under a surface appearance of Christianization and Hispanicization.

The rapid victory of the conquerors actually owed less to Spanish military capacity than to the rebellion of groups subject to Aztec rule who became allies of the Spanish, seeing Spain as the new imperial power. The Nahuas, by custom, accepted the god of the new rulers as the overlord, but expected that the traditional gods of the local areas would continue to be worshipped. In the Colloquies between the Spanish friars and the native priests—written by Sahagún in 1560 but also representing dialogues that took place when the first twelve Franciscan missionaries arrived in 1519—the Nahua view is evident. The friars argue that the Nahuatl gods are false and demonic and that the Nahuas must cease to worship them and must be converted to the one true god. The native priests do not object to the advent of the Christian God, but they insist that worship of their own gods should continue, gods “who from time immemorial have provided the spiritual and material means through which they and their forebears have sustained life.”40

Long before Aztec imperial rule, Mesoamerica had been organized into altepetl, or independent self-governing territories, occupied by peoples who each had their own identity, religious centers, markets, and myths (either of migration or of being descended from the breakup of the Toltec empire). The Aztecs did not change this system; rather, they simply turned many of these altepetl into tribute-paying subject peoples. Others, such as the Tlaxcalans, remained fiercely independent and were never subdued by the Aztecs. The Tlaxcalans were among those who were first conquered by the Spanish and then became their allies against the Aztecs. When the Aztec empire was destroyed, these altepetl communities remained and became the basis of Spanish administrative rule.

This situation explains the apparent rapidity of the spread of Spanish rule and Catholicism among the native peoples in the first decades after the conquest. In effect, the conquerors simply gave a Spanish veneer to what continued to be the organizational and cultural structure of the existing ethnic communities. The encomiendas (territories given to Spanish leaders for agricultural production and evangelization), the parishes, and the municipalities were all formed based on the existing altepetl communities.41 Religious life also followed this structure. Local leaders became both the heads of municipalities and the leading laity of the parishes, who often owned the land on which the church was built. The temple that had represented the local community and its god was replaced as the center of worship by the parish church, often built on or near the existing site and with the same stones as the earlier temple.

The altepetl were themselves divided into constituent subcommunities (calpolli), each with its own leadership and religious center. These in turn were divided into neighborhoods or households. These subcommunities were accustomed to rotating the leadership of the altepetl. This structure continued to be the basis of parish and government administration under the Spanish. Parish lay sodalities, or cofradias, dedicated to specific patron saints, were based on these traditional units. The Nahuas adapted the Spanish concept of saints to their own understanding of local patron gods, often picking a saint who had similar characteristics and whose feast day was near that of their traditional god.42

Many traditional religious practices continued, now directed to the Christian God and saints: the burning of copal incense, dancing and singing, marching in processions, offering flowers and ears of corn, engaging in divination and healing, and pricking with thorns to draw blood. Although they expressed very different worldviews, many Spanish Catholic practices were, on the surface, similar to Nahuatl practices, which aided this transition. Healing could now be understood as receiving miraculous favors from a saint, often manifest in a revered image. The Spanish practice of penitential selfabuse, beating with whips and wearing spiked chains, bore some resemblance to Nahuatl self-bleeding. For the Spanish, such selfabuse expressed the subduing of the sinful body; for the Nahuas, blood was the sacred fluid of life, which one returned to the gods, who had themselves given their lives to create the cosmos and humanity. This self-sacrifice of the Nahuatl gods seemingly was not far removed from the idea that Jesus Christ shed his blood, dying on the cross to redeem human beings. The image of a bloody Christ with a crown of thorns on his head and nails in his hand and feet might appear similar to the Nahuatl gods and priests who pricked themselves with thorns, shedding blood to create and sustain life.

The decision of the Spanish friars to evangelize the indigenous peoples in the Nahuatl language, creating dictionaries and grammars and an alphabetic spelling, allowed the Nahuas to express Christian ideas in language that recalled the traditional divinities. Just as Ometéotl was far away and did not appear directly in human life, but was instead represented by many second-rank deities, so the Christian God could be similarly far away, represented by the saints, who were the effective local expressions of God connected to particular local communities and territories. The different Marian cults of various local communities in Spain, each manifest in distinct miraculous images, such as the Virgin of Guadalupe de Extremadura and the Virgin de los Remedios, were to appear in miraculous stories and images of Mary in New Spain and were adopted by different indigenous communities.

The word for Mary as mother of God was translated as Totlaconantzin (our precious mother), a familiar term for the Nahuatl mother of the gods. This term for Mary paralleled the Nahuatl word used for God the father, Totlacotatzin (our precious father). The pairing of the two titles was reminiscent of the paired male and female expressions of the Nahuatl high God Ometéotl. By using these words, the Nahuas implicitly saw Mary as the female expression of God. Many Nahuatl words traditionally used for Tezcatlipoca, such as “Lord of the Near, the Close,” were used for God or Christ.

The friars were well aware of the dangers of referring to the Christian God and saints with Nahuatl words that had been used for Nahuatl deities, and they tried to substitute Spanish terms, such as dios. Spanish translations of the Nahuatl documents typically use Spanish Catholic terms, but examining the Nahuatl documents themselves reveals the extent to which familiar words from preconquest Nahuatl religion became the terms used for Christian concepts, thus translating these Christian concepts into the Nahua worldview.43

The first generation of Franciscans, who did the pioneering study of Nahuatl culture and language, were very concerned about indigenous “idolatry” hiding under superficial Catholicism. From Spanish Christian humanism (Erasmianism), they had developed a vision of a pure, apostolic Christianity planted in the New World that would replace the corrupt Christianity of Europe. But by the middle of the sixteenth century, these Franciscans were being replaced by nonorder bishops and Creole (American-born Spanish) clergy. The influence of the Counter-Reformation and the Jesuits, who arrived in 1572, was hostile to such “apostolic purity” and less concerned with possible syncretism. It was in this environment that the cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe, infused with indigenous elements, would develop on the hill of Tepeyac.

The history of the cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe is heavily contested, particularly in regard to the cult's early development in the sixteenth century. Fierce disputes have raged between those who believe that a humble Indian, Juan Diego, saw the apparitions in 1531 and had the image of the Virgin miraculously implanted on his cloak and those who see this whole story as a pious fiction of the seventeenth century, arguing that the image was painted by a skilled Indian artist trained by the Spanish. The following account details what I have come to regard as the likely history of the origins and early development of this cult, but it focuses primarily on the meaning of the Virgin of Guadalupe for Mexican religious and national identity. It is here that we see the extraordinary variety of interpretations that have been and are being attached to this Marian symbol.

It is possible that a small shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe of Extremadura was connected with Tepeyac (Tepeyacac, in Nahuatl) sometime before 1550, although there is no way to know how long before. Part of Cortés's army camped on this hill (which lies northeast of what was the lake area in which Tenochtitlán was built) in preparation for the siege of the Aztec capital in 1521.44 Cortés and many of his men came from the Spanish region of Extremadura and brought a devotion to the Virgin of Guadalupe of Extremadura with them to New Spain. When they returned to Spain, they visited this shrine and offered donations in thanks for their victories. The region of Extremadura and the image of the Virgin found there (named Guadalupe for the river of that name nearby) were themselves connected with the history of the Spanish struggle against the Moors.

According to the legendary account, the small wooden statue of the Virgin of Guadalupe at Extremadura was carved by Saint Luke. It eventually found its way to Spain, as a gift from Pope Gregory the Great to San Leandro, the archbishop of Seville, in the seventh century. The statue, of Byzantine style, pictured a seated and dark-complexioned Mary with the Christ child in her arms. When the city of Seville was captured by the Moors in the eighth century, a group of priests escaped with the statue and buried it in the hill of Extremadura, near the river of Guadalupe. In the early fourteenth century, the Virgin Mary was believed to have appeared to a poor herdsman who had lost his cow. She told him to tell priests to come and dig at the place where she appeared. They came, discovered the old statue, and built a chapel to house it.

The statue soon became an object of pilgrimage for those who believed in its miraculous healing powers. The shrine was entrusted to the Hieronymite order, which had close ties to the royal dynasty of Castile. Veneration of the Virgin of Guadalupe proliferated, and many subsidiary shrines were created with copies of the statue.45 It is possible that one of Cortés's men carried a print or small statue of the Virgin of Guadalupe at Extremadura, which might have become the model for the painting of the Virgin on Juan Diego's cloak. Although the statue revered at Extremadura was of a seated woman with a child in her arms, and hence did not resemble the painting, the shrine at Extremadura contained a second image of Our Lady over the oratory, surrounded by a sunburst with thirty-three rays and standing on an upturned moon. Some copy of this—the typically European image of Mary as the woman of Revelation 12 and as the Immaculata—could have been the model for the Mexican painting.46 It is likely, then, that the name “Virgin of Guadalupe” was derived from a connection to the Virgin of Extremadura.

Some time before 1556, an Indian painter trained by the Spanish to decorate churches probably painted an image of the Virgin on maguey cloth, the cloth woven from the maguey cactus plant that was used for rough Indian cloaks. Such Indian painters were well known for their skill (fig. 44). The painting associated with the shrine of the Virgin of Guadalupe at Tepeyac began to draw pilgrims to the shrine, based on a belief in its miraculous healing powers. In 1556, we find the first definite reference to veneration of the Virgin of Guadalupe at Tepeyac. In that year, a dispute broke out between the bishop of Mexico City, Alonzo de Montúfar, and the Franciscan provincial, Francisco de Bustamante, over the archbishop's sermon of September 6 encouraging devotion to the Virgin of Guadalupe.

In a counter-sermon on September 8, 1556, Bustamante protested the promotion of this devotion. The archbishop then ordered an investigation, whose records were kept, although not published until 1888–1890, hence becoming the center of modern criticism of the historicity of the apparitions.47 At the time, this dispute reflected the struggle to replace the “purist” hopes of the Franciscans for a repristinated apostolic Christianity with a Counter-Reformation baroque devotionalism that focused on visual images. Underlying the dispute was also the effort of bishops from the diocesan clergy to wrest power from the orders, especially the Franciscans.

In his protest, Bustamante described the devotion to Guadalupe as without historical foundation, based on a painting done by an Indian and encouraging the very idolatry that the Franciscans had sought to overcome in their missionary philosophy:

Nothing is better calculated to keep the Indians from becoming good Christians than the cult of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Ever since their conversion they have been told they should not believe in idols, but only in God and our Lady.... To tell them now that an image painted by an Indian could workmiracles will utterly confuse them and tear up the vine that has been planted. Other cults like that of Our Lady of Loreto have great foundations, so it isastounding to see the cult of Guadalupe without the least foundation.48

FIGURE 44

Virgin of Guadalupe, c. seventeenth century. Painting on maguey cloth cloak, exhibited in the shrine of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Mexico City.

In this protest, Bustamante clearly had never heard of apparitions of Mary appearing to Juan Diego, disclosed to the first bishop of Mexico City, the Franciscan Juan de Zumárraga. Bustamente also believed that the image had been painted by an Indian. He protested the cult arising around this image, but the image itself was not understood to have been miraculously produced.

The growing cult of Guadalupe was also of concern to the Franciscan pioneer of Nahuatl studies Bernadino de Sahagún. In his General History of the Things of New Spain, completed in 1576–1577, Sahagún expressed his reservations about the growing veneration of the Virgin of Guadalupe under the name of the ancient Mother Goddess Tonantzin. He noted that the hill of Tepeyac had long been the site of veneration of the Aztec Goddess; Indians came there from distant areas to offer sacrifices at the temple to Tonantzin. “And now that there is a church of Our Lady of Guadalupe, they call her Tonantzin, taking advantage that the preachers call Our Lady, the Mother of God, Tonantzin.” Sahagún protested the translation of Mary's title as Mother of God into the Nahuatl word Tonantzin, saying that it should instead be translated as Diosinantzin. He was alarmed that, because the title Tonantzin was being used for Mary, the Indians were coming from distant lands to worship Guadalupe, understanding her to be the continuation of the old Aztec Mother Goddess. “It appears a satanic invention to palliate idolatry under the equivocation of this name Tonantzin.”49

Clearly, Sahagún knew of no tradition of apparitions or miraculous production of the image of Guadalupe. His only concern was that the Indians flocking to the church of Guadalupe at Tepeyac might understand Guadalupe Tonantzin as a Goddess, the representative of the Nahuatl Mother Goddess and the female side of a dual God in new form. Sahagún's protests have been understood in modern times to mean that an Aztec Goddess named Tonantzin had a temple on the hill of Tepeyac, but this has been questioned. Tonantzin was a title for the maternal aspect of any Aztec goddess, not the name of a particular goddess. When it was used as a title for Mary, the maternal aspect of the Aztec Goddess could be read into the Spanish Marian cult by Nahua Christians. This seems to be what happened, rather than the cult of Guadalupe intentionally replacing an earlier temple or cult of an Aztec Mother Goddess at this particular site.50

Despite these Franciscan protests, devotion to the Virgin of Guadalupe continued to grow, and the first church was built in 1555 or 1556 by Montúfar.51 Apparently, both Indians and Spaniards came to the site, although Guadalupe was never the patron of an indigenous altepetl but was always associated with the Mexico City region generally.52 In 1566, Alonso de Villaseca, a wealthy mine owner, donated a life-size silver and copper statue of the Virgin, which became an object of devotion, although we do not know what it looked like. It was melted down for candlesticks at the end of the seventeenth century, when the painted image was firmly established as the cult object of the shrine.53 By the seventeenth century, the church had grown too small, and a second one was built in 1622.

There was a growing belief in the power of the Guadalupe painting to work miracles, not only for individuals but also for the community as a whole. In 1629, the archbishop of Mexico City brought the Guadalupe painting to the national cathedral to implore the Virgin's help in abating the flood waters that had covered the city. When the floods receded, the painted cloak was returned to the church at Tepeyac, escorted by both the viceroy and the archbishop and carried through the decorated streets accompanied by music and fireworks. In this role, Guadalupe paralleled the cult of the Virgin de los Remedios, whose image was similarly brought to the national cathedral in times of drought, in hopes of bringing rain.54

Despite this growing devotion, no document or account of the period mentions apparitions or the miraculous origin of the image until the middle of the seventeenth century. In 1648, Miguel Sánchez, a well-known preacher, published The Image of the Virgin Mary, Mother of God, of Guadalupe, Miraculously Appeared in the City of Mexico, Celebrated in Her History by the Prophecy of Chapter Twelve of Revelation.55 In this book, Sánchez tells what would become the established story of the appearances of Mary to the Indian Juan Diego. Mary demands that Juan Diego tell the archbishop to build a church to her at the place of her appearance on Tepeyac. The bishop is skeptical and demands a “sign.” Mary responds by instructing Juan Diego to pick flowers that miraculously appear on the hill (out of season, for it is December) and take them to the archbishop in his cloak. When Juan Diego opens the cloak to release the flowers in the presence of the archbishop, the image of the Virgin is found miraculously printed on the cloak. As further proof of the miraculous powers of this Virgin, Juan Diego's uncle, who had been on the point of death, is cured, at the very moment when the Virgin promised Juan Diego that this would happen.

This account follows the lines of a typical European apparition story. Sánchez's narrative is interspersed with biblical interpretations. He claims that the image that appeared on Juan Diego's cloak was the “true image” of Mary herself. This image had appeared in the mind of God from all eternity and was the very image that the apostle John had seen in his vision of the woman “clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head the crown of stars,” recorded in Revelation 12. Following a long-established exegesis of this passage from Revelation, Sánchez understands the image to represent both Mary and the church.

After each segment of the story of the apparitions, Sánchez makes biblical digressions. He compares Juan Diego to Mary Magdalene and the bishop to the apostles who did not at first believe her when she told them of Christ's resurrection. They doubted because she was a woman of bad reputation, a recent convert, like the Indians, who have been possessed by the “seven devils of idolatry.” Tepeyac is called the new Mount Tabor, Juan Diego the new Moses, and Mexico the Promised Land. The first pilgrims who hasten to the shrine are compared to the shepherds that hastened to see the baby Jesus and his mother in Bethlehem. These comparisons situate the apparitions in the context of biblical typologies and their reenactment in Mexico.

The following year, a second account of the apparitions appeared in the Nahuatl language, written by Luis Laso de la Vega, the vicar of the shrine of Guadalupe. This account lacks the biblical digressions of Sánchez's narrative. The story is told in an elegant Nahuatl that recalls many of the forms of Aztec rhetoric. Mary addresses Juan Diego as “my dear little son,” “my youngest child,” while Juan Diego addresses Mary as “my patron, personage, Lady, my youngest child, my daughter.” But other than the use of these polite forms of address, de la Vega's account follows the general lines and often the wording of the Sánchez book, although in Nahuatl.56

Several key questions arise. Did Sánchez make up the story of the apparitions out of whole cloth, or was he dependent on earlier traditions for which we have no historical records? Was de la Vega's account copied from Sánchez, or was he using an earlier account written shortly after the apparitions by an Indian skilled in Nahuatl, an Indian trained in the college of Sahagún to be trilingual in Latin, Spanish, and Nahuatl? The structure of Sánchez's book, which takes the form of biblical commentary on each segment of the story of the apparitions, suggests that he had at least some source for it. He claimed that there was no written source but that he had followed an unwritten tradition. He had set himself the tasks of making a written version of this story and unveiling its deeper meaning in the light of biblical typologies.57

But the archives of Archbishop Juan de Zumárraga, the supposed recipient of the miraculous image, contain no records of the apparitions. Zumárraga was a Franciscan, who would have shared the order's hostility to images. He was reputed to have gathered up and burned the Aztec codices of the archives of Tlatelolco.58 Discussions of the shrine of Guadalupe in the sixteenth century and the first half of the seventeenth century also reflect no knowledge of such apparitions. It is likely that the story of the apparitions and the miraculous appearance of the image began to develop in oral tradition in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. There are two brief accounts in Nahuatl that seem to reflect this earlier oral tradition, but the tale was only locally known, as one apparition story among others, and not taken seriously.59 It was this oral tradition that Sánchez drew upon to write the story and elaborate his biblical commentary.

From the late seventeenth century into the twentieth century, the tradition grew that de la Vega's story of the apparitions was independent of Sánchez's book, that it had not been written by de la Vega himself but had been copied from an earlier account written by an Indian trained by Sahagún at a time shortly after the apparitions were seen. This Indian was later identified with Antonio Valeriano (d. 1605), a noted native Nahuatl scholar and governor.60 In a recent study of the similarities between Sánchez's Spanish account and de la Vega's Nahuatl account, three contemporary Nahuatl scholars—Lisa Sousa, Stafford Poole, and James Lockhart—concluded that de la Vega's story of the apparitions was dependent on Sánchez. There was no earlier Nahuatl account written by an Indian hand, although de la Vega may have used skilled Indian writers to polish the Nahuatl language of his version.61

De la Vega himself addressed a letter to Sánchez after reading his book, in which he said, “All the while my predecessors and I have been slumbering Adams, though all the while we possessed this New Eve in the paradise of her Mexican Guadalupe.”62 This might mean that de la Vega had never known of the apparition stories before he read Sánchez's book, even though he was the vicar of the Guadalupe shrine. In his letter, he also refers to himself as “entrusted with the sovereign relic of the miraculous image of the Virgin Mary, whom the angels alone merit to have for their companion.” This statement could simply mean that the image was known to produce miracles, rather than implying that the image itself had been produced by a miracle. At the least, de la Vega testifies that he had not understood the deep theological significance of the image before reading Sánchez, whether or not he had heard of the apparition story earlier.63

The year 1663 saw the beginning of a long campaign by the cathedral chapter of Mexico City to persuade the Vatican to accept the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe, based on revelations of Mary in Mexico, and to give the cult its own feast day of December 12. Until then, the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe had been associated with the general feast of the nativity of Mary on September 8. Occasionally, the Hieronymite order that controlled the cult of Mary of Extremadura in Spain sought to claim the alms from the Mexican shrine on the grounds that it was an extension of their own.64 There had already appeared in 1660 a version of Sánchez's account of the apparitions, but without the biblical exegesis by the Spanish Jesuit Mateo de la Cruz. He used old church calendars to establish the date on which the miraculous image was revealed to Archbishop Zumárraga as December 12, 1531. In 1663, the cathedral chapter in Mexico City asked the pope to recognize December 12 as the feast day of the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe, thus clearly severing her cult from that of Mary of Extremadura in Spain.

At issue was the establishment of a unique revelation of Mary in Mexico. Mary could be seen in some sense as the founder and patron of the Mexican church. By appearing in Mexico, she established an independent basis for her (and God's) relation to Mexican Christianity, not simply dependent on Spain. Creole Mexicans could see Mary as one of them, a Mary birthed in Mexico. In order to prove their case to the Vatican, historical records of the apparitions going back to 1531 were necessary. But none were to be had. The search of the archives of Archbishop Zumárraga yielded no evidence that he had known of the apparitions or the miraculously produced image.

Lacking records, the Mexican church elicited signed testimonies from elderly Mexicans, both Spanish and Indian, that they had known of the apparitions from their youth and had heard of them from their parents and grandparents. In this way, church officials hoped to provide evidence of an oral tradition going back to 1531. These testimonies, from twenty people, Indian and Spanish, were obtained through a set of questions that itself contained an account of the apparitions and tended to elicit the very answers that were sought.65 The petition from the cathedral chapter, supported by the Jesuits and other religious orders, was sent to Seville in 1666 to present the case to Rome, along with a direct letter to Pope Alexander VII. But this petition did not find favor in Rome, where the Vatican feared an excessive proliferation of miraculous images.

With the 1666 petition, there was also an account of the apparitions, drawn mainly from de la Cruz, by one Luis Becerra Tanco, who produced a readable version of Sánchez's story without the biblical digressions. But this account was complicated by Tanco's claim that the Indians not only had preserved an unbroken oral tradition concerning the apparitions but also had painted scenes of the story and produced a narrative in Nahuatl. This was the first effort to claim the existence of a document contemporaneous with the apparitions written by an Indian, although this document was not yet identified with Valeriano.66

The Holy See did not accept December 12 as the feast of the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe until 1754. Nonetheless, from the late seventeenth century, Mexican theologians and preachers grew ever more daring in their eulogies of the Virgin's miraculous image. Preachers such as José Vidal de Figueroa expounded on Sánchez's idea that the image of the Virgin represented the exact representation of Mary in the mind of God for all eternity.67 The light around the image of Mary was said to represent Christ's divinity, while Mary herself incarnated Christ's humanity. The Jesuit chronicler Francisco de Florencia even claimed that the very image of Guadalupe made Mary physically present, just as Christ was physically present in the Eucharist. This line of eulogy became common in Mexican theologizing on Guadalupe during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.68

In 1709, a new and enlarged basilica was erected at Tepeyac to replace the 1622 church. In 1739, the Virgin of Guadalupe was proclaimed patron of Mexico City, followed by her acclamation as patron of all New Spain in 1750. Mexico was seen as a chosen nation, uniquely converted through the appearance of Mary, and there was speculation that the Indians were the ten lost tribes of Israel. Just as the United States would take over the myth of England as a chosen nation, adding its vision of itself as a paradisal promised land, so Mexico took over the myth of Spain as an elect people and interpreted Mexico as a promised land uniquely chosen by Mary.69 The phrase from Psalm 147:20, “non fecit taliter omni natione” (it was not done so to any other nation), referring to Israel as a chosen people, was applied to Mexico, uniquely favored by Mary.70

The effort to provide biblical roots for the Mexican church was expressed in a controversial sermon preached on the feast of Guadalupe on December 12, 1794, by Fray José Servando Teresa de Mier. In this sermon, Mier speculated that St. Thomas had already evangelized Mexico in apostolic times and that the image of Guadalupe, identical to that seen by St. John in Revelation 12, had been revealed in Mexico at that time. He argued that the Nahuas had preserved in their religious traditions a distorted memory of this early evangelization—Quetzalcóatl was a dim remembrance of St. Thomas, and the image of Mary imprinted on St. Thomas's cloak was remembered in traditions about Teotenantzin (another name for the beloved Mother Goddess) and other goddesses. This sermon caused furious criticism, and its view was not generally accepted. But it represented early efforts to rehabilitate Nahuatl religion, to see it not simply as idolatry and demon worship, by arguing that its central religious figures contain memories of “true” religion, conveyed to the Mexicans in the apostolic age.71

In September of 1810, the parish priest of Delores, Miguel Hidalgo, raised the cry of rebellion against Spanish rule of Mexico. The Virgin of Guadalupe was imprinted on the banners of the revolution. The war cry of those who joined the rebellion was “Long live the Virgin of Guadalupe and death to the gachupines” (Spaniards born in Spain, who had continued to be the ruling elite of church and state in New Spain). The Virgin of Guadalupe, as the symbol of an elect Mexican national identity, had become the patron of revolution. But the top church leaders, still largely royalist, were by no means willing to let this national symbol be carried off by the rebels. More conservative Creole leaders saw Hildago and other revolutionaries as fomenting a class rebellion that would also undo the hierarchy of Creoles over mestizos and Indians. The priest revolutionaries, Hildago and José Maria Morelos, as well as many other rebels, were captured and executed.

Mexico would establish its independence from Spain, but under a Creole leadership that would curb deeper class and race transformation of society. By the mid-nineteenth century, however, Mexico had become deeply divided between liberals, who wanted a radical secularization of public life and separation of church and state, and conservatives, who wanted to retain the alliance of the Mexican state and the Catholic Church. Under the reform laws of Benito Juárez, much church land was confiscated, and the Catholic Church's control was removed from many areas of public life, such as education.

At the same time, a critical history of Mexico began to be developed by a new generation of historians, such as Joaquín García Icazbalceta (1824–1894). The long-delayed publication of the documents from the 1556 investigation of the Virgin of Guadalupe apparitions raised the question of the historicity of this tradition. Icazbalceta clearly believed that the apparitions could not be defended as historical fact, although, as a faithful Catholic, he was reluctant to say so openly and accepted devotion to the Virgin as piety.72

The Catholic Church saw itself as deeply embattled by both the legal and the intellectual attacks of liberalism. It sought to position itself as the guardian of the true Catholic faith against both of these attacks. Its spokesmen reviled and sought to refute the historians. It sponsored a number of public displays of Guadalupan piety, such as the 1895 “coronation” of the Virgin of Guadalupe, to reclaim public space for the church in Mexico. At the same time, the Mexican Catholic Church began to realize that separation of church and state also freed the church itself from subordination to the state inherited from Spanish rule. By positioning itself in a new relation to the Vatican, as the head of an independent world church, the Mexican church began to reorganize itself and rebuild its educational and other institutions independently of the Mexican state.73

This use of Marian piety to defend the church against secular liberalism also reflected the struggles going on in Europe, with Pius IX's repudiation of liberalism in the Syllabus of Errors and the declaration of papal infallibility (1870). In France, the apparitions of Mary at Lourdes in 1858, followed by the promotion of mass pilgrimages to Lourdes, had become displays of the power of the French church against secular liberalism. This French Marian Catholicism influenced a similar politics of anti-liberalism through promotion of Guadalupan mass public piety in Mexico.74 Despite the effort of the rebels of 1810 to claim Guadalupe for revolutionary change, Guadalupan piety appeared firmly in bed with rightist politics and hostility to critical historical thought at the end of the nineteenth century.

During the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1935, similar conflicts arose over the ideological ownership of Guadalupe. The followers of the peasant revolutionary Emiliano Zapata carried the banner of Guadalupe. But Zapata was assassinated, and the revolution was “institutionalized” in the rule of the PRI (Party of the Institutionalized Revolution). Under President Plutarco Elías Calles (1924–1928), militant anticlerical laws were passed that imposed heavy fines and imprisonment for violating the constitutional separation of church and state by engaging in religious education or maintaining religious orders or Catholic trade unions. The church was prohibited any public display of religion, even the wearing of clerical garb in public.

These laws pushed Mexico into a new civil war, with rural priests risking execution for defying the laws. In this “Cristero” rebellion, parts of the rural peasantry arose against the urban elite of Mexico City. The Cristeros' slogan was “Viva Cristo Rey y Santa Maria de Guadalupe.” On their banners, the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe appeared in the white center between the green bars of the Mexican flag. Below the image of Mary were the words Reina y Madre Nuestra, Salvanos (our queen and mother, save us).75 During this upheaval, the politics of Guadalupan piety were partly shifted. No longer only on the side of a landed conservative class, the church now stood with a rebellious poor peasantry, mestizo and Indian, who saw themselves as both Catholic and oppressed by the secular elites of the ruling party.

Not accidentally, it was precisely in the context of the Cristero rebellion that the movement to beatify Juan Diego arose. The figure of Juan Diego had been largely neglected in earlier Creole Guadalupan devotion, but now he became the perfect symbol for a pious Catholic who was at the same time a poor Indian. That Mary chose to reveal herself to such an Indian meant not only that Mexico itself was at root Indian but also that Mary's revelation had enshrined the union of Indian and Spaniard. In Juan Diego, the Catholic Church found a “Catholic” way of taking over the revolutionary claim that Mexico was a mestizo nation, a new people born of the merger of the two peoples. Mexico was both uniquely mestizo and Catholic—which cast militant secularism as a deviation from true Mexican identity.

This effort to canonize Juan Diego moved slowly, as had the earlier effort to prove the historicity of the apparitions. Canonization made it necessary to prove that Juan Diego had actually existed as a historical person. He was unknown in sixteenth-century records, appearing first in the apparition traditions of the mid-seventeenth century. Thus, the effort to canonize him flew in the face of historical criticism of these apparition traditions. Despite these questions, Pope John Paul II moved to beatify Juan Diego in 1990.76 Juan Diego was proposed for canonization as a saint by this same pope in December of 2001 and canonized in July of 2002.77 But the attempt to claim Juan Diego as a symbol of Mary's favor to the Mexican Indians goes back earlier, receiving a marked emphasis as far back as the 1930s. It has borne rich ideological fruit in new efforts to “indianize” Catholicism in recent decades.

The second half of the twentieth century saw a gradual reconciliation of the Catholic Church and the Mexican state. The laws against public displays of religion were allowed to remain unenforced and then were gradually rescinded. The Mexican church more and more reappeared in public space, to the alarm of a Mexican secularism concerned with maintaining a high wall of separation between church and state. But the political stances of the Catholic Church were no longer only on the right. Liberation theology and notions of a “preferential option for the poor” as the true Christian gospel had pushed the faith and politics of many priests and bishops to the left. The bishop of Cuernavaca, Sergio Mendez Arceo, was Marxist and pro-Cuban; the bishop of Chiapas, Samuel Ruíz, was pro-Indian and suspected by the Mexican government of standing behind the Zapatista rebellion of 1994.78 Other Mexican prelates were suspected of conspiring to undermine these bishops of the left, siding with the Vatican's suspicions of liberation theology and with moneyed corporate elites. Thus, conflict among right, left, and center came to mark the politics of Catholic commitment. When the PRI was defeated in the election of 2000 and the new president, Vicente Fox, took office, he made a point of going first to Mass at the shrine of the Virgin of Guadalupe. A Mexican president in 2000 could now publicly present himself as a Guadalupano.

During the 1980s and 1990s, liberation theology, feminist theology, and “Indian” theology interacted to both reinterpret Guadalupe and reclaim indigenous religious traditions as positive. Liberation theology developed a reinterpretation of the traditional Jewish and Christian dualism between the true God and idolatry. For liberation theologians, such as Pablo Richard, idolatry, or the worship of false gods, was seen as a false use of the name of God to justify violence, injustice, and death.79 Such idolatry took place among nominal Christians whose “god” was money, power, or war. The true God was the God of life, the God of love and justice for all. This new understanding of the true God and idols allowed a new approach to the confrontation of Spanish Catholicism and the Nahua people.

In her article “Quetzalcóatl y el Dios Cristiano,” Elza Tamez, professor of biblical studies at the Universidad Bíblico de América Latina in Costa Rica, applied this understanding of God and the idols to the Mexican conquest.80 Tamez argues that the Nahuas had an authentic tradition of the God of life in Quetzalcóatl, but that the Aztecs distorted this native vision of a beneficent God whose representative served the community and forbade human sacrifice. The Aztecs, she writes, co-opted Quetzalcóatl into their religion of war and human sacrifice, led by the war God Huitzilopochtli.

In effect, there was within Nahuatl religion both a true understanding of God as the God of life and a distorted view of God as an idol of death. But the Spanish also brought with them an idolatrous god of death that justified their violent conquest and the destruction of the Indians. This Spanish idol of death was far from the true God of life of Jesus Christ. The Indian leaders deplored the violence of this Spanish god but were also able to glimpse behind the Spanish teaching something of a true God of life who resembled Quetzalcóatl. Whether or not Tamez correctly interprets the Aztec tradition, her essay represents a new way for Christians to find positive religious meaning in indigenous religion and at the same time critique their own traditions, without imagining an apostolic evangelization of Mexico by St. Thomas. Tamez assumes a universal revelation of the true God accessible to peoples of all religions as well as a general tendency to will to power that distorts religion into a system of domination. As a Protestant, Tamez does not discuss the Tonantzin-Guadalupe relationship.

Brazilian Catholic feminist theologians Ivone Gebara and Maria Clara Bingemer attempted a feminist reinterpretation of Mary in their book Mary, Mother of God, Mother of the Poor.81 Mary, in opting for the poor, also opts for women as the oppressed of the oppressed. Gebara and Bingemer sought to free “Marianismo” from the taint of being a tool of the conservative church to pacify and subordinate women. In Mary, women are empowered to struggle for justice, emulating Mary in the Magnificat, who lauds herself as the one through whom “the mighty are put down from their thrones and the poor lifted up” (Luke 1:52). Bingemer and Gebara see the Virgin of Guadalupe, in particular, as representing God's choice of the conquered, oppressed Indian people of the Americas and the vindication of their despised culture, uniting Mary with the Mother Goddess Tonantzin.82

The reinterpretation of the Virgin of Guadalupe as supporting the struggles for justice of the poor mestizos, the Indians, and women took on new creativity in the United States, where Chicanos as a whole see themselves as oppressed by the dominant Anglos. In the farmworkers' strikes, led by César Chávez, banners imprinted with the picture of the Virgin of Guadalupe led the movement of insurgent Mexican agricultural laborers.

In Goddess of the Americas, a group of essays written originally in English and authored mostly by Chicanos and Mexicans living in the United States, writers and artists skeptical of the historicity and piety of the traditional devotion nonetheless reclaim the meaning of Guadalupe.83 Some authors celebrate Guadalupe as a covert continuation of Mexican goddess traditions. They see this presumed continuation of goddess traditions under the cover of Guadalupe as empowering their struggles as feminists. One such writer, Clarissa Pinkola Estés, author of Women Who Run with the Wolves,84 imagines a Guadalupe who can lift up the women whom society despises and connect them with elemental earth energies:

My Guadalupe is a young woman gang leader in the sky

She does not appear as a woman in light blue

She is serene, yes, with the serenity of a great ocean.

She obeys, yes, as the dawn obeys the line of the horizon.

She is sweet, yes, like an immense forest filled with sweet maple trees.

She has a great heart, an enormous sanctity

And like any young woman gang leader, a solid pair of hips.

Her embrace sustains us all... 85

The history outlined in this chapter indicates the remarkable ideological amplitude of the figure of the Virgin of Guadalupe. She can be adapted to Creole, mestizo, or Indian celebration of identity as well as the merger of these identities in “la Raza” (the new race). She can be used by the left and the right, revolutionaries and reactionaries, feminists and defenders of traditional femininity. In all this diversity, she is always a way of claiming “Mexicanidad” (Mexicanness), a Mexicanness that remains convinced, in the midst of victories and defeats, that, if all else fails, there is a divine mother who loves us. Or, in the words of Octavio Paz, “The Mexican people, after more than two centuries of experiments and defeats, have faith only in the Virgin of Guadalupe and the National Lottery.”86