7.

Working Toward Healing

“These natural laws [of mindfulness], core to the nature of our existence, can offer insight into how we relate to racial distress—specifically, what supports more distress and what supports release from distress.”1

—Ruth King

As noted in the introduction, we offer a recipe for racial healing, and each chapter so far has offered ingredients. The natural laws of mindfulness that Ruth King refers to above infuse this recipe with yet another ingredient. Restorative justice, trauma awareness and resilience, history, connecting, circles, action, and the elements of this chapter all combine to work toward racial healing, with the intention of transforming damaged or broken pieces of ourselves into wholeness (to the degree possible). We’re talking about making an entirely new meal to bring to the table of brother and sisterhood for what Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. envisioned as our Beloved Community. As a chef would do, you will decide the level of value you derive from these various ingredients—these healing approaches—perhaps altering the amounts or replacing one or more with something different that works for you or your community.

We believe one of the most important questions to ask is, “What would racial healing look like?” It will look different to different people, of course, depending on many factors: who people are, where they come from, what they’ve experienced, and their connection to the wounds that need healing. The vision for healing also changes and grows as we listen to each other’s stories and better understand the wounds.

What Healing Looks Like

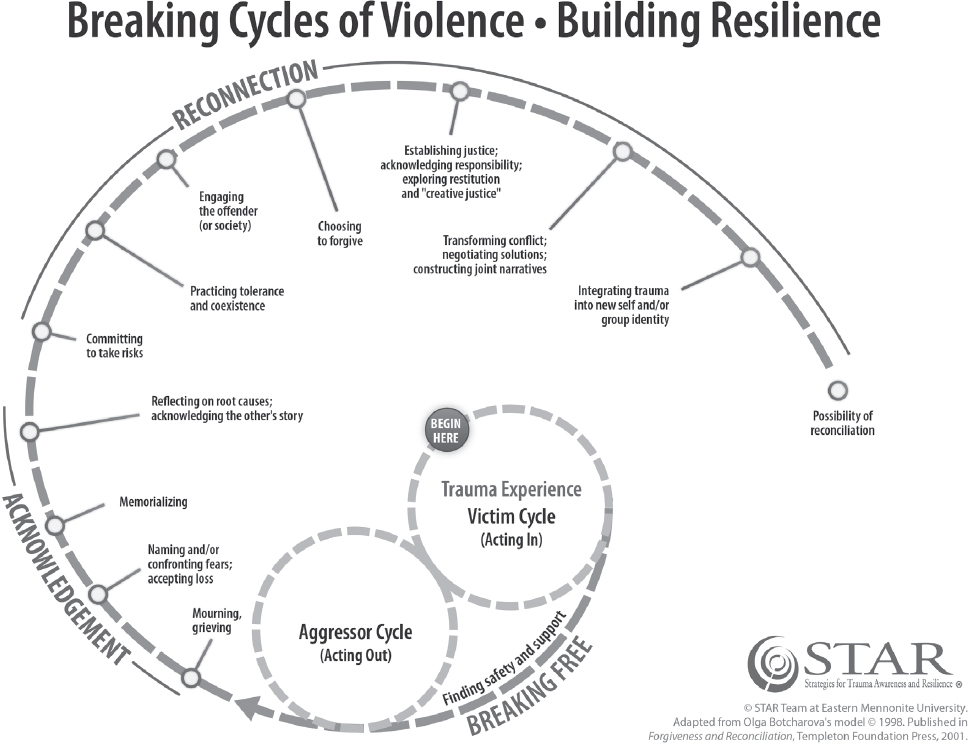

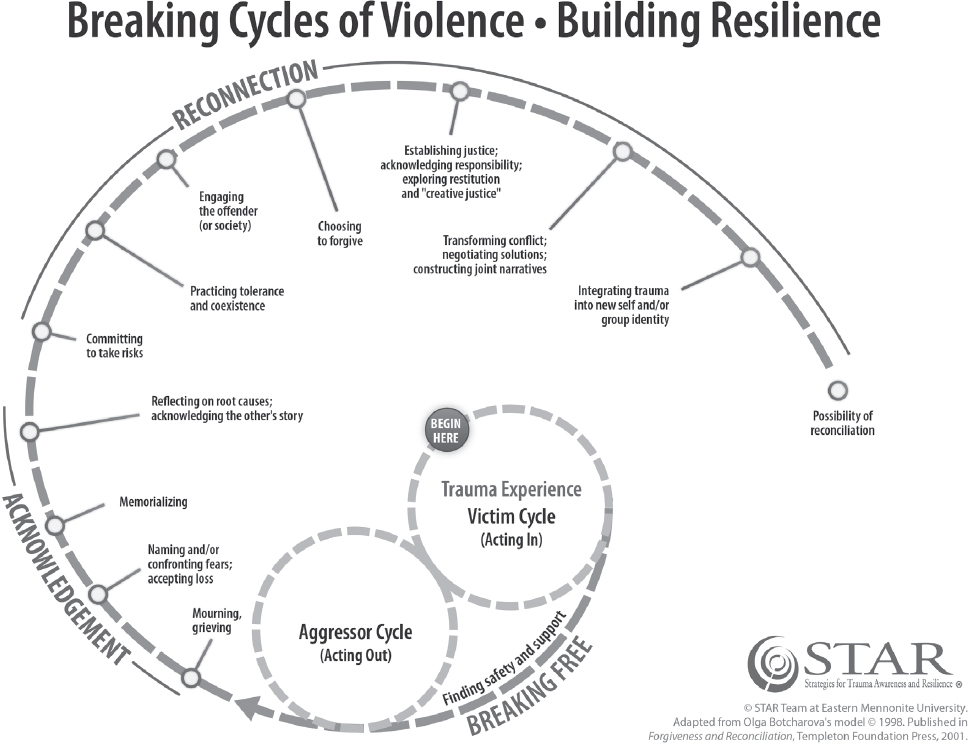

Strategies for Trauma Awareness and Resilience (STAR) teaches that a healing journey begins with breaking free from the cycles of violence and moving toward healing through three stages (see Figure 3). The first stage includes finding safety and support. The second stage involves acknowledging what happened to create the wound and responding to the harm with mourning, confronting fear and accepting loss, and committing to take risks.

The final stage toward healing involves reconnecting with parts of ourselves that we may have buried, and with others we may have avoided, shunned, or “othered.” This stage suggests some challenging questions:

• Can we engage perpetrators of harm—be they individuals, whole communities, or society in general—and, in doing so, address structural racism?

Figure 3.

• Can we choose to forgive, understanding that forgiveness is complex and engages our deepest emotions?

• Can we let go of our desire for revenge and still hold perpetrators of racial woundedness accountable?

• How can our various stories of being wounded and causing wounds become a shared narrative? How can we integrate the results of our wounds into our new, evolved selves?

This is the difficult and essential journey we travel on the road toward racial healing.

The W. K. Kellogg Foundation’s Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation (TRHT) enterprise provides an example of what is possible on this journey. TRHT teams pondered several questions, the first of which was, “What would the country look and feel like if we jettisoned the belief in a hierarchy of human value and the narratives that reinforce that belief?” In other words, what would healing look like? Here are a few excerpts from their vision:

“We imagine an America where all people are seen through the lens of our common humanity and we see ourselves in one another. This new society is characterized by love, interconnectedness, mutual respect, accountability, empathy, honoring nature and care for the environment. In this society, healing and justice flow from authentic relationships.”

“Our children and grandchildren feel safe and secure in who they are and proud of their heritage and culture.”

“Memorials serve as a reminder of suffering but also the effort and strength that emerged from it. We no longer carry the pain, fear and shame of history, for we have discovered how to look at our past with courage and honesty.”2

With this chapter’s focus on healing, we invite you to consider what is shared here as you read the following story. Then pause for a few minutes and ask yourself, “What else would healing look like?”

Olga

by Sri Lalitambika Devi

My friend, Olga, has had cancer for two years. I live with her in the women’s shelter where I am a residential caretaker. What can I do? I steam mango with sesame seeds, because she thinks this will fight the cancer. I cook whatever else she asks for. She is more a caretaker to me than I am to her, looking in on me each night to smile and say “Good night.”

Olga has always liked the name of our shelter. Saranam. The rolling syllables sound mysterious; they are from India. Recently, I thought to translate the name into English for a more universal message. Saranam would be better understood as Refuge.

This name, she takes issue with. “Refuge. It sounds like a place for slaves to hole up, a stop on the Underground Railroad,” she says. She is African American and sensitive to history. “You cannot call this place Refuge,” she tells me. And so, we stay as Saranam.

I think about how most of shelter guests are African American and wonder if the cycle of poverty is the new incarnation of slavery that keeps people from living in freedom. I ask Olga, “Why do you think that even after emancipation, so many still struggle for socioeconomic equality?” “Freedom is yet to come,” she responds. “We must strive onward.”

One evening, I speak of Harriet Tubman as a spiritual leader like Mohammed or Gandhi. In India, we would call her a mahatma, a great soul. She is one who achieved hard-won freedom but continued to fight for the liberation of her brothers and sisters, risking her life to guide those still enslaved to the Promised Land. “She is my hero,” I say. “You are mine,” Olga says. “You don’t have to do this, to care about the homeless, but still you offer refuge along the way to our liberation.”

Over time, Olga’s condition deteriorates, and the powers that be decide she will be transferred to a medical shelter. She does not want to go, but she tells me not to worry; we will both be all right. I miss her, but I carry on. I take refuge in simple tasks like chopping vegetables or folding laundry. This is what Olga hopes for in the end. Clean sheets and no pain. I know that one day she will follow the Drinkin’ Gourd, and when I look up into the night sky, she will be there among the infinite points of light.

Multiple Interconnected Paths to Healing

What does healing look like? Just as with recipes, there are a variety of resources and modalities to help address woundedness of body, mind, and spirit. What follows are some that can be used by individuals, groups, and communities. Adapting multiple techniques—these and others—can help personalize and localize the healing journey.

Prayer and Faith. The foundation of most spiritual paths includes concepts of prayer, love, community, faith in a higher power, being in the right relationship (with each other, God, a higher power, the Universe), justice, equality, peace, accountability, kindness, and so on; all the basic tenets of being whole and healed. Participating in a faith community, traveling a spiritual path, engaging in prayer, or maintaining a prayerful approach to life can all contribute to racial healing.

Ceremony and Ritual. Observing and commemorating traumatic events have been part of human life for as long as we have walked the Earth. Ceremony and ritual unify us and connect us with the sacred, with mystery and wonder. Ritual is often considered more formal, a rite that is practiced the same way time after time. Ceremony is often considered less formal, more spontaneous and creative. Ceremonies and rituals can be used to preserve existing traditions and beliefs as well as launching new ones. They can be an honest expression of ethical, moral, and spiritual principles and value and help us connect with our spiritual and sacred beliefs and with whatever we consider to be Divine. They can be cleansing experiences that contribute to racial healing.

Mindfulness Meditation. The ability to be mindful in the face of stress and trauma can improve our ability to respond to ourselves and others with kindness, compassion, and wisdom. Ruth King writes, “Being mindful of race is not just about sitting meditation. Mindfulness practice is about changing hearts, and ultimately, having a mindful life.”3 In Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score, we learn the critical importance of self-awareness and being in touch with our inner selves, noticing when we become annoyed, nervous, or anxious so we can shift our perspective from our automatic, habitual reactions. Studies have also shown that loving-kindness meditation increases feelings of social connection and can improve automatically activated, implicit attitudes toward stigmatized social groups (“the other”).4

Memorials, Monuments, and Museums. Statues, memorials, and objects displayed in museums reflect choices, values, and priorities about which historical figures or occurrences are worthy of being remembered. Many that are located in public spaces have become quite controversial. Some have been removed. These memorials influence those who view them. For example, what might someone who views a statue of Martin Luther King Jr. be thinking, versus someone who views a statue of Stonewall Jackson? How might black or white people view such statues differently? Within what context, and with what signage, are various statues located and perceived?

One way to work toward racial healing is to memorialize and contextualize that which caused traumatic racial wounds, as well as the people and events that have contributed to justice, peace, and transformation. Two new museums have made significant additions to the national conversation about race. The National Museum of African American History and Culture is located on the National Mall in Washington, DC, in view of the White House and the Washington Monument; its location signifies the importance and power of place. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, created by the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, “is the nation’s first memorial dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people, people terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow, and people of color burdened with contemporary presumptions of guilt and police violence.”5

Apology and Forgiveness. Some of the most profound, and often feared, interactions among people include offering or accepting an apology and forgiving others and ourselves. The benefits of these actions go right to the core of racial healing.

Many white people say or think, “I never enslaved anyone. I wasn’t even alive during slavery or even Jim Crow days. Why should I apologize?” Aaron Lazare, in On Apology, offers a response when he writes “… just as people take pride in things for which they had no responsibility (such as famous ancestors, national championships of their sports teams, and great accomplishments of their nation), so, too, must these people accept the shame (but not guilt) of their family, their athletic teams, and their nations. Accepting national pride must include willingness to accept national shame when one’s country has not measured up to reasonable standards.” He continues that “people have profited from these actions. Imperialistic acquisition of land and the use of slave labor by a nation, for example, may continue to benefit future generations of citizens. Such beneficiaries, while not guilty, may feel a moral responsibility to those who suffered as a result of the offense.”6 When a person or institution apologizes sincerely and adequately, it is an acknowledgment and expression of remorse for the harm(s) committed. This apology should include a commitment to change and plans for acts of repair/reparation to help restore dignity. It should also demonstrate that the person or institution is committed to shared values and increased safety in the future. In short, the apology must do more than admit past wrongdoing; it must demonstrate that the apologizer is willing and prepared to make amends and to continually make a best effort to do better.

Forgiveness, like apology, is hard work. Within this racial healing approach, such work, often a difficult process, is intended to be done in community. Apology and forgiveness are voluntary acts that cannot be forced. When someone offers forgiveness, they give up many of the emotions, thoughts, and actions seen in the cycles of violence (revenge, dehumanization of “the other,” and the good vs. evil narrative). Their healing is no longer tied to other people changing their behaviors and attitudes. There may be varying degrees of forgiveness, related to the profound, centuries-long harm of slavery and racism; the adequacy and quality of the apology; and the particular people involved. It is critical to acknowledge historic and present-day power imbalances and work to overcome them. Successful forgiveness shifts our relationship to power and helps break down walls between two sides. Breaking down systems of power allows us to connect in ways we otherwise cannot. This work is also about being tender with oneself as a way to deconstruct internalized racial oppression. Self-forgiveness is critically important in breaking down barriers and important in overcoming the often-debilitating feelings of shame and guilt. Lazare devotes Chapter 11 of his book to the inextricable tie between apology and forgiveness.

Mourning and Rebirth. When hurt or injury is experienced, it is important to acknowledge the pain and create space to grieve. Grief is often tied to death, and in the case of racial harm, death symbolizes the letting go of shame, guilt, and what holds one back from moving toward racial healing. In many cultures, death is acknowledged through ritual and ceremony. Parkes, Laungani, and Young assert that “death rituals often define the death, the cause of death, the dead person [or thing/feeling you’re letting go of], the bereaved, the relationship of the bereaved with one another and with others, and the meaning of life. Failing to carry out necessary rituals or having [them] shortened or undermined can leave people at sea about how the death occurred, who or what the deceased is, how to relate to others, how to think of self, and much more.”7

There is also dedicated time to mourn. In the Jewish tradition, shiva represents the seven days of mourning. “On returning from the funeral, the mourner(s) should be offered a meal prepared by others […] and during the whole shiva period they may not work, nor should they prepare their own food; their needs must be tended as far as possible by others.”8 This part of the ritual had a high emphasis on care and community support to provide time and space for mourning.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which honors more than four thousand African American people lynched by white mobs in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, encourages the collecting of dirt from sites of lynchings across America, remembering and saying aloud the names of victims, and inscribing their names on permanent monuments. These are living rituals representing death and mourning, and also rebirth. Whatever release happens through mourning lays the ground for something new to be born in that soil. Specifically, the Peace and Justice Memorial is a way to cleanse that space and name it as sacred, something other than simply a site of lynching.

There are many more healing resources available, and the book The Body Keeps the Score explores a wide range of possibilities. Many have used therapy, neurofeedback, PTSD treatment, yoga, breathwork, and the Hawaiian process of Ho‘oponopono. Others turn to the arts and find healing in music, theater (including playback theater), painting, writing, and dance (including InterPlay and Dance Exchange). Whatever feels like it might help, try it. Trust your heart. Work with friends in a supportive community. Teach your children. Be that change in the world you wish to see. Together, we can work toward racial healing by any and all means available.