CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Rachael Morris‐Jones

Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Introduction

The aim of this book is to provide an insight for the non‐dermatologist into the pathological processes, diagnosis, and management of skin conditions. Dermatology is a broad specialty, with over 2000 different skin diseases, the most common of which are introduced here. Pattern recognition is key to successful history‐taking and examination of the skin by experts, usually without the need for complex investigations. However, for those with less dermatological experience, working from first principles can go a long way in determining the diagnosis and management of patients with less severe skin disease. Although dermatology is a clinically oriented subject, an understanding of the cellular changes underlying the skin disease can give helpful insights into the pathological processes. This understanding aids the interpretation of clinical signs and overall management of cutaneous disease. Skin biopsies can be a useful adjuvant to reaching a diagnosis; however, clinico‐pathological correlation is essential in order that interpretation of the clinical and pathological patterns is put into the context of the patient.

Interpretation of clinical signs on the skin in the context of underlying pathological processes is a theme running through the chapters. This helps the reader develop a deeper understanding of the subject and should form some guiding principles that can be used as tools to help assess almost any skin eruption.

Clinically, cutaneous disorders fall into three main groups.

- Those that generally present with a characteristic distribution and morphology that leads to a specific diagnosis – such as chronic plaque psoriasis (Figure 1.1), basal cell carcinoma, and atopic dermatitis.

- A characteristic pattern of skin lesions with variable underlying causes – such as erythema nodosum (Figure 1.2) and erythema multiforme.

- Skin rashes that can be variable in their presentation and/or underlying causes – such as lichen planus and urticaria.

Figure 1.1 Psoriasis with nail changes.

Figure 1.2 Erythema nodosum in pregnancy.

A holistic approach in dermatology is essential as cutaneous eruptions may be the first indicator of an underlying internal disease. Patients may, for example, first present with a photosensitive rash on the face, but deeper probing may reveal symptoms of joint pains etc. leading to the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Similarly, a patient with underlying coeliac disease may first present with blistering on the elbows (dermatitis herpetiformis). It is therefore important not only to take a thorough history (Box 1.1) of the skin complaint but in addition to ask about any other symptoms the patient may have and examine the entire patient carefully.

The significance of skin disease

Seventy per cent of the people in developing countries suffer skin disease at some point in their lives, but of these, 3 billion people in 127 countries do not have access to even basic skin services. In developed countries the prevalence of skin disease is also high; up to 15% of general practice consultations in the United Kingdom are concerned with skin complaints. Many patients never seek medical advice and will use the internet to self‐ diagnose and self‐treat using over‐the‐counter preparations.

The skin is the largest organ of the body; it provides an essential living biological barrier and is the aspect of ourselves that we present to the outside world. It is therefore not surprising that there is great interest in ‘skin care’ and ‘skin problems’, with an associated ever‐expanding cosmetics industry and so‐called cosmeceuticals. At the other end of the spectrum, impairment of the normal functions of the skin can lead to acute and chronic illness with considerable disability and sometimes the need for hospital treatment.

Malignant change can occur in any cell in the skin, resulting in a wide variety of different tumours, the majority of which are benign. Recognition of typical benign tumours saves the patient unnecessary investigations and the anxiety involved in waiting to see a specialist or waiting for biopsy results. Malignant skin cancers are usually only locally invasive, but distant metastases can occur. It is important therefore to recognise the early features of lesions such as melanoma (Figure 1.3) and squamous cell carcinoma before they disseminate.

Figure 1.3 Superficial spreading melanoma.

Underlying systemic disease can be heralded by changes on the skin surface, the significance of which can be easily missed by the unprepared mind. So, in addition to concentrating on the skin changes, the overall health and demeanour of the patient should be assessed. Close inspection of the whole skin, nails, and mucous membranes should be the basis of routine skin examination. The general physical condition of the patient should also be determined as indicated.

Most skin diseases, however, do not signify any systemic disease and are often considered ‘harmless’ in medical terms. However, due to the very visual nature of skin disorders, they can cause a great deal of psychological distress, social isolation, and occupational difficulties, which should not be underestimated. A validated measure of how much skin disease affects patients' lives can be made using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). A holistic approach to the patient both physically and psychologically is therefore highly desirable.

Descriptive terms of clinical inspection

All specialties have their own common terms, and familiarity with a few of those used in dermatology aids with diagnostic skills as they relate to the underlying pathology. The most important are defined below.

- Macule (Figure 1.4). Derived from the Latin for a stain, the term macule is used to describe changes in colour (Figure 1.5) without any elevation above the surface of the surrounding skin. There may be an increase in pigments such as melanin, giving a black or brown colour. Loss of melanin leads to a white macule. Vascular dilatation and inflammation produce erythema. A macule with a diameter greater than 2 cm is called a patch.

- Papules and nodules (Figure 1.6). A papule is a circumscribed, raised lesion, of epidermal or dermal origin, 0.5–1.0 cm in diameter (Figure 1.7). A nodule (Figure 1.8) is similar to a papule but greater than 1.0 cm in diameter. A vascular papule or nodule is known as a haemangioma.

- A plaque (Figure 1.9) is a circumscribed, superficial, elevated plateau area 1.0–2.0 cm in diameter (Figure 1.10).

- Vesicles and bullae (Figure 1.11) are raised lesions that contain clear fluid (blisters) (Figure 1.12). A bulla is a vesicle larger than 0.5 cm. They may be superficial within the epidermis or situated in the dermis below it. The more superficial the vesicles/bullae, the more likely they are to break open.

- Lichenification is a hard thickening of the skin with accentuated skin markings (Figure 1.13). It commonly results from chronic inflammation and rubbing of the skin.

- Discoid lesions. These are ‘coin‐shaped’ lesions (Figure 1.14).

- Pustules. The term pustule is applied to lesions containing purulent material – which may be due to infection – or sterile pustules (inflammatory polymorphs) (Figure 1.15) that are seen in pustular psoriasis and pustular drug reactions.

- Atrophy refers to loss of tissue, which may affect the epidermis, dermis, or subcutaneous fat. Thinning of the epidermis is characterised by loss of normal skin markings; there may be fine wrinkles, loss of pigment and a translucent appearance (Figure 1.16). In addition, sclerosis of the underlying connective tissue, telangiectasia or evidence of diminished blood supply may be present.

- Ulceration results from the loss of the whole thickness of the epidermis and upper dermis (Figure 1.17). Healing results in a scar.

- Erosion. An erosion is a superficial loss of epidermis that generally heals without scarring (Figure 1.18).

- Excoriation is the partial or complete loss of epidermis as a result of scratching (Figure 1.19).

- Crusted. Dry serous fluid forming a crust (underlying epidermis or dermis is usually disrupted) (Figure 1.20).

- Fissuring. Fissures are slits through the whole thickness of the skin.

- Desquamation is the peeling of superficial scales, often following acute inflammation (Figure 1.21).

- Annular lesions are ring‐shaped (Figure 1.22).

- Reticulate. The term reticulate means ‘net‐like’. It is most commonly seen when the pattern of subcutaneous blood vessels becomes visible (Figure 1.23).

Figure 1.4 Section through skin.

Figure 1.5 Erythema due to a drug reaction.

Figure 1.6 Section through skin with a papule.

Figure 1.7 Papules in lichen planus.

Figure 1.8 Nodules in hypertrophic lichen planus.

Figure 1.9 Section through skin with plaque.

Figure 1.10 Psoriasis plaques on the knees.

Figure 1.11 Bullae on the palm from multidermatomal shingles.

Figure 1.12 Section through skin showing sites of vesicle and bulla.

Figure 1.13 Lichenification due to chronic eczema in nickel allergy.

Figure 1.14 Discoid lesions in discoid eczema.

Figure 1.15 Inflammatory pustules secondary to contact dermatitis with Argon oil.

Figure 1.16 Epidermal atrophy in extra‐genital lichen sclerosus.

Figure 1.17 Ulceration in pyoderma gangrenosum.

Figure 1.18 Erosions (loss of epidermis) in paraneoplastic bullous pemphigoid.

Figure 1.19 Excoriation of epidermis in atopic dermatitis.

Figure 1.20 Crusted lesions in pemphigus vulgaris.

Figure 1.21 Desquamation following a severe drug reaction.

Figure 1.22 Annular (ring‐shaped) lesions in neonatal lupus.

Figure 1.23 Reticulate pattern in vasculitis.

Clinical approach to the diagnosis of rashes

A skin rash generally poses more problems in diagnosis than a single, well‐defined skin lesion such as a wart or tumour. As in all branches of medicine, a reasonable diagnosis is more likely to be reached by thinking firstly in terms of broad diagnostic categories rather than specific conditions.

There may be a history of recurrent episodes such as occurs in atopic eczema due to the patient's constitutional tendency. In the case of contact dermatitis, regular exposure to a causative agent leads to recurrences that fit from the history with exposure times. Endogenous conditions such as psoriasis can appear in adults who have had no previous episodes. If several members of the same family are affected by a skin rash simultaneously then a contagious condition, such as scabies, should be considered. A common condition with a familial tendency, such as atopic eczema, may affect several family members at different times.

A simplistic approach to rashes is to classify them as being from the ‘inside’ or ‘outside’. Examples of ‘inside’ or endogenous rashes are atopic eczema or drug rashes, whereas fungal infection or contact dermatitis are ‘outside’ or exogenous rashes.

Symmetry

As a general rule, most endogenous rashes affect both sides of the body, as in the atopic child, psoriasis on the legs or cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma (Figure 1.24). Of course, not all exogenous rashes are asymmetrical. Chefs who hold the knife in their dominant hand can have unilateral disease (Figure 1.25) from metal allergy whereas a hairdresser or nurse may develop contact dermatitis on both hands, and a builder bilateral contact dermatitis from kneeling in cement (Figure 1.26).

Figure 1.24 Symmetrical hypopigmented plaques of cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma.

Figure 1.25 Irritant eczema on dominant hand of chef.

Figure 1.26 Bilateral contact dermatitis to cement.

Diagnosis

- Previous episodes of the rash, particularly in childhood, suggest a constitutional condition such as atopic dermatitis.

- Recurrences of the rash, particularly in specific situations, suggest a contact dermatitis. Similarly, a rash that only occurs on photo‐exposed skin is highly suggestive of UV‐driven skin disease (Figure 1.27) such as chronic actinic dermatitis.

- If other members of the family are affected, particularly without any previous history, there may well be a transmissible condition such as scabies.

Figure 1.27 Chronic actinic dermatitis.

Distribution

It is useful to be aware of the usual sites of common skin conditions. These are shown in the appropriate chapters. Eruptions that appear only on areas exposed to sun may be entirely or partially due to sunlight. Some are due to sensitivity to sunlight alone, such as polymorphic light eruption, or a photosensitive allergy to topically applied substances or drugs taken internally.

Morphology

The appearance of the skin lesion may give clues to the underlying pathological process.

Changes at the skin surface (epidermis) are characterised by a change in texture when the skin is palpated. Visually one may see scaling, thickening, increased skin markings, small vesicles, crusting, erosions, or desquamation. In contrast, changes in the deeper tissues (dermis) can be associated with a normal overlying skin. Examples of changes in the deeper tissues include erythema (dilated blood vessels, or inflammation), induration (an infiltrated firm area under the skin surface), ulceration (that involves surface and deeper tissues), hot tender skin (such as in cellulitis or abscess formation), and changes in adnexal structures and adipose tissue.

The margin or border of some lesions is very well defined, as in psoriasis or lichen planus, but in eczema it is ill‐defined and merges into normal skin.

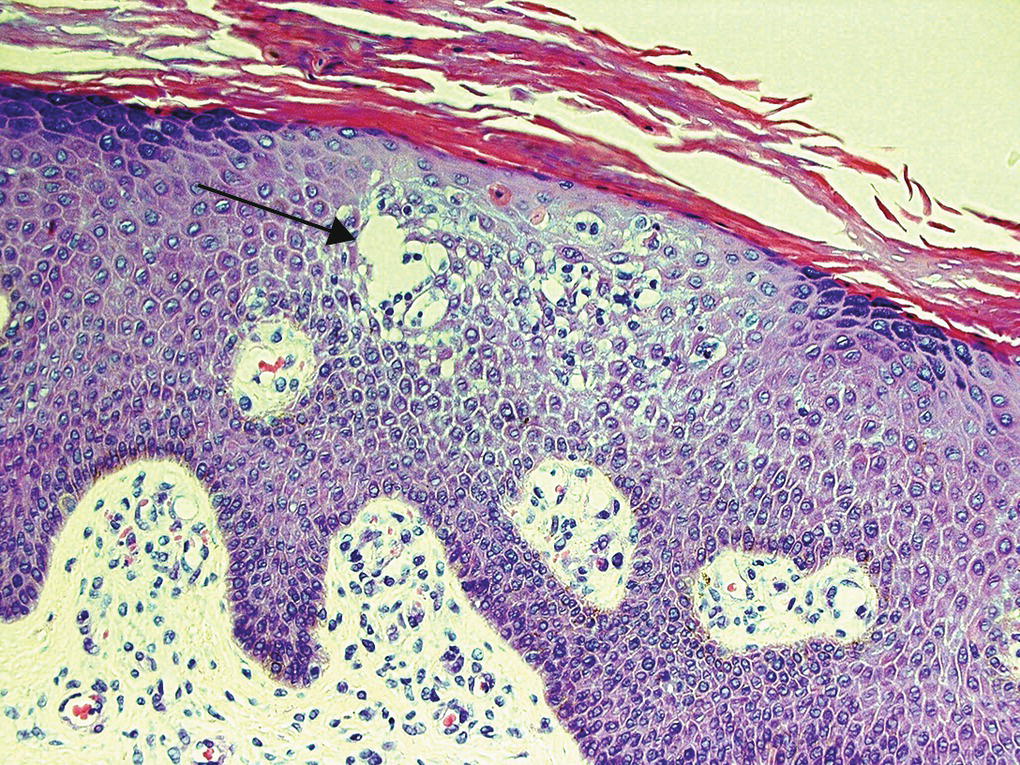

Blisters or vesicles occur as a result of

- oedema (fluid) between the epidermal cells (Figure 1.28)

- destruction/death of epidermal cells

- separation of the epidermis from the deeper tissues.

Figure 1.28 Eczema: intraepidermal vesicle (arrow).

There may be more than one mechanism involved simultaneously. Blisters or vesicles (Figures 1.29–1.33) occur in

- viral diseases such as chickenpox, hand, foot and mouth disease, and herpes simplex

- bacterial infections such as impetigo or acute cellulitis

- inflammatory disorders such as eczema, contact dermatitis, and insect bite reactions

- immunological disorders such as dermatitis herpetiformis, pemphigus, and pemphigoid and erythema multiforme

- metabolic disorders such as porphyria.

Figure 1.29 Vesicles and bullae in erythema multiforme.

Figure 1.33 Bullae from insect bite reactions.

Bullae (blisters more than 0.5 cm in diameter) may occur in congenital conditions (such as epidermolysis bullosa), in trauma, and as a result of oedema without much inflammation. However, those forming as a result of vasculitis, sunburn, or an allergic reaction may be associated with pronounced inflammation. Adverse reactions to medications can also result in a bullous eruption.

Induration is the thickening of the dermis due to infiltration of cells, granuloma formation, or deposits of mucin, fat, or amyloid.

Inflammation is indicated by erythema, which can be acute or chronic. Acute inflammation can be associated with increased skin temperature such as occurs in cellulitis and erythema nodosum. Chronic inflammatory cell infiltrates occur in conditions such as lichen planus and lupus erythematosus.

Assessment of the patient

A full assessment should include not only the effect the skin condition has on the patients' lives but also their attitude to it. For example, some patients with quite extensive psoriasis are unbothered while others with very mild localised disease just on the elbows may be very distressed. Management of the skin disease should take into account the patients' expectation as to what would be acceptable to them.

Fear that a skin condition may be due to cancer or infection is often present and reassurance should always be given to allay any hidden fears. If there is the possibility of a serious underlying disease that requires further investigation, then it is important to explain fully to the patient that the skin problems may be a sign of an internal disease.

The significance of occupational factors must be considered. In some cases, such as an allergy to hair dyes in a hairdresser, it may be impossible for the patient to continue his or her job. In other situations, the allergen can be easily avoided.

Patients often want to know why they have developed a particular skin problem and whether it can be cured. In many skin diseases these questions are difficult to answer. Patients with psoriasis, for example, can be told that it is part of their inherent constitution but that additional factors can trigger clinical lesions (Figure 1.34). Known trigger factors for psoriasis include emotional stress, local trauma to the skin (Koebner's phenomenon), infection (guttate psoriasis), and drugs (β‐blockers, lithium, antimalarials).

Figure 1.34 Possible precipitating factors in psoriasis.

Skill in recognition of skin conditions will evolve and develop with increased clinical experience. Seeing and feeling skin rashes ‘in the flesh’ is the best way to improve clinical dermatological acumen (Box 1.2).

Further reading

- Graham‐Brown, R., Harman, K., and Johnson, G. (2016). Lecture Notes: Dermatology, 11e. New York: Wiley‐Blackwell.

- Wolff, K., Johnson, R.A., and Saavedra, A.P. (2013). Fitzpatrick's Colour Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology, 7e. Oxford: McGraw‐Hill Medical.