CHAPTER 21

Genital Dermatoses

Fiona Lewis

St John's Institute of Dermatology, Guy's and St. Thomas' Hospitals, London, UK

Introduction

The genital site in both sexes is complex as it contains keratinised skin and non‐keratinised mucosa. There are specific diseases that affect the area but it may also be involved as part of disease elsewhere. The clinical appearances of easily recognisable disease on the rest of the skin are often altered because of the moist environment. Irritants, friction, and the specific bacterial flora can aggravate skin disease. Treatment requires modification as some topical treatments that prove useful at extra‐genital sites can be very irritant on the genital skin. As a general principle, ointments are always preferable to creams, and once‐daily application of any topical steroid treatment is sufficient. Simple ointment‐based emollients can be used as a soap substitute.

History and examination

A full history should include all the usual questions in a general dermatological history but in any patient with genital symptoms additional topics must be covered. A sexual history, effects on micturition, bladder, or bowel symptoms and a full obstetric and gynaecological history in women must be included.

The examination should be performed with good lighting and magnification if needed. A methodical approach to include all the areas, including the perianal skin, should be adopted. Speculum examination of the vagina is needed in those with erosive disease or intra‐epithelial neoplasia. Further examination of the skin, mouth, scalp, and nails may give useful diagnostic information.

The appearance of the genitalia can vary significantly, and it is very important to know the normal variants of the vulva and penis as this will avoid unnecessary investigation or surgical excision.

Angiokeratomata are common in both sexes. They are most commonly seen on the labia majora and scrotum (Figure 21.1). They are benign vascular tumours with overlying keratotic epithelium, measuring 1–3 mm in diameter and frequently multiple. No treatment is required.

Figure 21.1 Angiokeratomas, multiple small vascular lesions on labia majora.

Vestibular papillae are small rounded projections seen at the vestibule in up to 50% of premenopausal women. They are not human papillomavirus (HPV) related, do not cause symptoms and require no treatment.

Fordyce spots are sebaceous glands that can be very prominent in young women. They are seen on the inner labia minora as small yellow spots. Hart's line is the junction between the keratinised skin and non‐keratinised mucosa.

Pearly penile papules occur in up to 20% of young men and are seen in the coronal sulcus. The histology is that of an angiofibroma.

Eczema

Several types of eczema can affect the genital skin and it is important to distinguish between them. Atopic eczema often spares the genital area.

Treatment of eczema in the genital area is with regular emollients and a mild topical steroid as needed.

Seborrhoeic eczema – this is the most common endogenous eczema seen in the genital area. Patients usually have a history of this elsewhere with scalp and facial lesions.

Irritant eczema – this is a very common problem in children and in older women with urinary incontinence. Diffuse erythema is seen over the outer vulva or the shaft of the penis. It frequently affects the perianal skin where symmetrical erythema sometimes with scaling is seen on the buttocks. It is frequently aggravated by excessive washing, particularly if irritant cleansing solutions are used.

Allergic contact dermatitis – common allergens at this site include fragrances, preservatives, antibiotics, caine local anaesthetics used in topical treatments, and rubber accelerators. In the acute presentation, the skin may be severely inflamed (Figure 21.2) with weeping and eroded areas. Secondary bacterial infection is often a problem. If suspected, the patient requires patch testing to try to identify the cause. Treatment is with avoidance. Topical steroids and emollients will be needed initially with potassium permanganate soaks 1 : 10000 if wet and eroded.

Figure 21.2 Extensive erythema in acute allergic contact dermatitis.

Lichen simplex

Lichen simplex is the end result of the itch‐scratch cycle. Intense itch, often enough to disturb sleep, and the resulting rubbing leads to extensive lichenification of the involved skin. The genital area is a common site for this condition and until treated, it often spreads to involve the perianal region. Lesions are mostly seen on the labia majora (Figure 21.3) and scrotum. Treatment is with emollients and potent topical steroids on a reducing regimen for two to three months. In those where perianal involvement is predominant, patch testing should be considered.

Figure 21.3 Lichen simplex with lichenification and excoriation of labia majora.

Balanitis and balano‐posthitis

Balanitis is the term used to describe inflammation of the glans penis and posthitis is inflammation of the foreskin. There may be an underlying infection (e.g. Candida, Streptococcus) or dermatosis but most cases are non‐specific, and no primary cause is found. Treatment is with bland emollients and a mild topical steroid used as needed.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis can involve the ano‐genital skin in isolation or as part of generalised disease. The classic silvery scaling is lost at flexural sites due to the moist environment and it presents, with well‐defined erythematous plaques, sometimes with minor scaling at the spreading edge (Figure 21.4). Itching is the main symptom but fissuring is common, leading to soreness and dyspareunia in both sexes. In females, the outer labia majora and mons pubis are generally affected. In men, the glans, shaft of the penis, and scrotum are most commonly involved. Extension to the perianal skin and gluteal cleft is common in both sexes.

Figure 21.4 Vulval psoriasis with well‐defined plaques affecting labia majora and inguinal folds.

Topical treatments for psoriasis need to be modified in the genital area as several of these used at other sites are too irritant on the ano‐genital tissues. Regular emollients and a moderately potent topical steroid used on a reducing regimen over four to six weeks is helpful. Treatment is usually required intermittently to maintain control of the disease. Calcineurin inhibitors are sometimes helpful as topical steroid‐sparing agents but are rarely sufficient alone to treat the problem.

Lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is the most common dermatosis to affect the genital area. It occurs in both sexes but is much more common in females, where there are two peaks of incidence, one in childhood (about three to five years of age) and the second in adults post menopause. About 20% of cases will start in the reproductive years.

The aetiology is not known. Genetic factors may be involved, but previous theories of an infective trigger with Borrelia burgdorferi have not been substantiated, and are not thought to be relevant. There is clinical evidence for the role of urine under occlusion in males, with a dysfunctional meatal valve.

In women, but not in men, there is a link with other autoimmune conditions such as hypothyroidism and pernicious anaemia but this is not necessarily a causative factor.

Histology shows a dense band of collagen under a thinned epidermis. There is a marked lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis which is pushed down more deeply in the later stages of the disease.

In females, the predominant symptom is pruritus. If the skin fissures, this can be painful and perianal fissuring in children gives rise to the very common symptom of constipation. Narrowing of the introitus can cause dyspareunia. In males, the major symptoms relate to phimosis in the uncircumcised and problems with intercourse and micturition.

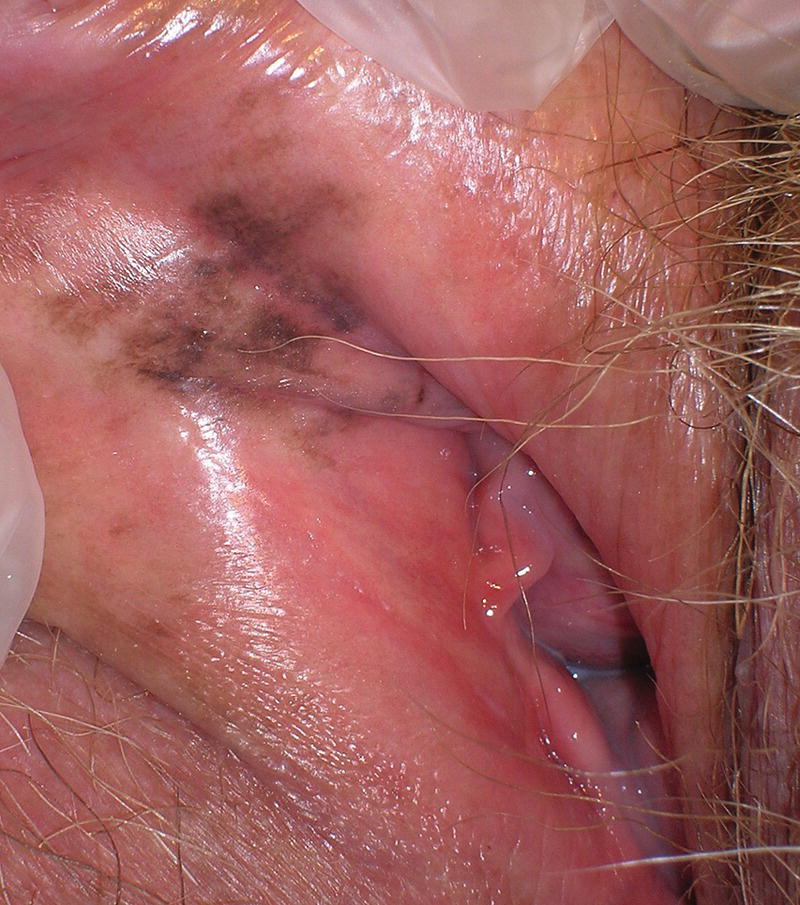

The classic clinical appearance is white sclerotic patches. These mainly affect the inner labia majora and minora (Figure 21.5), clitoral hood and perineum. Ecchymosis is pathognomonic of LS and is due to rupture of superficial dermal vessels. In some patients this can be dramatic and is common in children, leading to the erroneous diagnosis of child sexual abuse. Alteration of the normal architecture with resorption of the labia minora and sealing of the clitoral hood (Figure 21.6) can occur until treatment is started. Fusion of the inner labia majora may then narrow the introitus. LS does not affect the vagina.

Figure 21.5 Vulval lichen sclerosus with white sclerotic plaques on inner labia minora and clitoral hood.

Figure 21.6 Vulval lichen sclerosus – architectural change with loss of labia minora and narrowing of the introitus. Ecchymosis is also seen.

In males, lesions are most common on the glans (Figure 21.7) and inner foreskin resulting in phimosis. In the circumcised male, obliteration of the coronal sulcus may be seen. Stenosis of the urinary meatus requires expert urological assessment.

Figure 21.7 Lichen sclerosus affecting the glans penis.

The differential diagnosis of LS includes lichen planus (LP), mucous membrane pemphigoid and vitiligo. Some patients with LS also have vitiligo at the same site.

There is overwhelming evidence for the use of an ultra‐potent topical steroid such as clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment as the treatment of choice for LS in both adults and children. A three‐month tapering induction regimen of once daily for a month, alternate days for the second month and then twice weekly is used. Thereafter, the treatment should be tailored to maintain control of symptoms and signs. Unfortunately, scarring cannot be reversed with treatment but should stop progressing once treatment is started, hence the importance of early diagnosis and treatment. Circumcision in males can be very helpful in those who have phimosis. However, surgery is not undertaken in women unless there is severe scarring causing functional problems or a malignancy has developed.

There is a 3–4% risk of developing a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in LS. However, appropriate management and good control of disease reduces this significantly. Those who do develop problems usually have atypical features with hyperkeratosis being a particular risk. These patients often respond poorly to treatment and should be monitored carefully in a specialist clinic. Any atypical areas should be biopsied.

Lichen planus

LP is one of the inflammatory dermatoses where genital involvement is frequent. In those who present with classic cutaneous LP, genital lesions will be found in about 25% of men and 50% of women. Three main types of LP occur on the genital skin.

- Classic (papulosquamous) LP. The lesions are very similar to the flat‐topped violaceous papules seen elsewhere. These are generally seen on the shaft of the penis and the outer labia majora, but can affect the mucosal surfaces and Wickham's striae are often seen at the edge. Oral lesions are common in this type. The lesions may be pruritic but can be asymptomatic.

- Erosive LP. The lesions in erosive LP are erythematous glazed areas seen at the vestibule (Figure 21.8) or on the glans penis (Figure 21.9). Scarring can lead to alteration of the normal anatomy. A variant of erosive LP is recognised – the vulvo‐vaginal‐gingival or peno‐gingival syndrome. Erosions on the walls of the vagina can lead to vaginal scarring preventing intercourse. The patients may have disease at other sites including the lacrimal ducts, auditory meati, and oesophagus.

- Hypertrophic LP. This is rare but is important as there is a risk of malignant change in this type of LP. Thickened nodules develop which are extremely itchy.

Figure 21.8 Erosive vulval lichen planus with vestibular erosions and architectural change.

Figure 21.9 Erosive lichen planus of glans penis.

The first‐line treatment of LP is an ultra‐potent topical steroid used initially for three months as for lichen sclerosus. Patients often require ongoing treatment and those with erosive LP need specialist management to monitor and treat potential complications from scarring. Systemic agents including hydroxychloroquine and mycophenolate have been used.

Other inflammatory dermatoses

Autoimmune bullous disease

Pemphigus vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid can involve the genitalia as part of more generalised disease. Mucous membrane pemphigoid is a specific entity which specifically involves mucous membranes. The immunofluorescence pattern is identical to that seen in bullous pemphigoid. Scarring can occur similar to that seen in LS and LP.

Linear IgA disease is uncommon but the childhood form (chronic bullous disease of childhood) usually starts on the genital and peri‐genital skin. Crops of blisters, often in an annular pattern, are seen. Deposition of IgA in a linear pattern at the basement membrane zone is diagnostic.

Manifestations of systemic disease

Behçet's disease

Behçet's disease is a multisystem syndrome without any diagnostic tests and so the diagnosis is clinical supported by scoring systems. Oral ulceration is always present and at least two other manifestations must be present. These include genital ulceration, arthritis, ocular lesions, folliculitis, and pathergy. The genital ulcers occur on the labia majora, scrotum, and glans penis. They are typically larger than aphthae and heal with scarring.

Crohn's disease

Crohn's disease of the ano‐genital skin can occur with or without gastrointestinal involvement. Deep ‘knife‐cut’ fissures, ulcers, oedema are characteristic features. Perianal and natal cleft involvement with tags and fissures is common. Treatment includes oral antibiotics, systemic immunosuppression, and biologics such as adalimumab and infliximab. Patients need multidisciplinary care.

Acrodermatitis enteropathica

This eruption with characteristic erythematous, eroded lesions around the peri‐oral and genital skin occurs mainly in children and is due to zinc deficiency. The cutaneous lesions resolve rapidly with zinc supplementation.

Reiter's syndrome

This is a reactive triad of arthritis, conjunctivitis, and psoriasiform circinate lesions (circinate balanitis) preceded by an infection such as Shigella or non‐gonococcal urethritis. It is extremely rare in females.

Acanthosis nigricans

The typical hyperpigmented, velvety plaques may affect the inguinal folds but lesions are likely to be present at other sites.

Ulcers

The investigation of a patient presenting with a genital ulcer starts with a good history. In addition to the usual information, details of the sexual history and travel are particularly important as several sexually transmitted infections can present with ulceration. The causes of genital ulcers are seen in Table 21.1.

Table 21.1 Causes of genital ulceration.

| Infection – sexually transmitted | Syphilis, chancroid, herpes simplex, lymphogranuloma venereum, donovanosis |

| Infection – non‐sexually transmitted | Epstein–Barr virus, herpes zoster, tuberculosis, amebiasis |

| Drug eruptions | Erythema multiforme, toxic epidermal necrolysis, fixed drug eruption |

| Inflammatory | Behçet's syndrome, Crohn's disease, Lipschutz ulcer, aphthae |

| Trauma | Trauma, dermatitis artefacta |

| Malignancy | SCC, BCC, cutaneous lymphoma, melanoma |

Aphthous ulcers

Aphthous ulcers, identical to those seen in the mouth occur on the vulva, but are rarely seen in males. Painful superficial ulcers with an erythematous rim and sloughy base are seen primarily on the inner labia majora. Healing occurs within a few days but a moderately potent topical steroid once daily can aid resolution.

Lipschutz ulcer

These acute ulcers are only seen in young females. Large, painful ulcers appear on the inner labia majora and rapidly enlarge over about 24 hours. There is frequently a history of an upper respiratory tract infection or flu‐like illness in the preceding 10 days and they are probably a reactive phenomenon. A short course of prednisolone 10–15 mg/day for a week is very helpful together with adequate pain relief. Healing without scarring occurs in about three weeks.

Drug eruptions

The genital skin can be involved in severe drug eruptions such as erythema multiforme and toxic epidermal necrolysis. A fixed drug eruption may present on the genital skin, more commonly in males. Bullae and ulceration can occur. The problem may be intermittent as it is often related to medication taken as needed e.g. non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, fluconazole.

Pigmentation

Changes in the normal pigmentation of the genital skin are common. Post‐inflammatory hypo‐ or hyperpigmentation is often seen, particularly after classic type LP and psoriasis. Genital lentigines can be seen as part of rare syndromes e.g. LAMB (lentigines, atrial myxoma, and blue naevi).

Melanosis

Melanosis is common on the genital skin and occurs in males and females. There is an increase in the melanin in the basal melanocytes but no increase in the numbers of melanocytic cells. The appearances are often alarming with very dark, irregular areas of pigmentation which may be multiple (Figure 21.10). A biopsy should always be done as the histological features are characteristic. There is no evidence of progression to melanoma.

Figure 21.10 Vulval melanosis – irregular pigmentation inner labia.

Genital naevi

Naevi at genital sites are often atypical both in their clinical and histological appearances. Expert histological examination is vital to prevent the mis‐diagnosis of melanoma.

Infections

Common genital infections will be discussed here but in any patient where a sexually transmitted infection is suspected or confirmed, referral to a genito‐urinary clinic for diagnosis, management, and contact tracing should be done.

Pubic lice

Infection with pubic lice causes intense pruritus. Egg cases may be seen on the pubic hair. Treatment is with topical permethrin.

Scabies

The genital skin is frequently involved in scabies and the inflamed, pruritic papules on the shaft of the penis or outer labia majora are characteristic of the infestation. Treatment is with topical permethrin.

Candidiasis

Candida species are part of the normal flora in females and infection occurs when the balance of the flora is upset e.g. after antibiotics or in immunosuppressed patients. Over 90% of candidiasis is caused by Candida albicans. A cheesy discharge is seen, with marked pruritus and soreness if the skin fissures. Generally topical treatment with azole compounds will be sufficient but for those with a dermatosis where the infection is secondary, oral treatment with fluconazole 150 mg stat dose is more effective.

Herpes simplex infection

Groups of painful vesicles which resolve within seven days are typical. The infection is not always sexually transmitted and both herpes simplex viral (HSV) 1 and 2 viruses are seen. The problem is recurrent in some patients and a prolonged course of aciclovir 200–400 mg bd can be helpful. In immunosuppressed patients, herpetic lesions can be atypical and mimic malignancy.

Human papilloma virus (HPV) infection

Many different HPV types affect the ano‐genital area. Types 6 and 11 cause 90% of genital warts and types 16 and 18 are associated with the majority of vulva intra‐epithelial neoplasia (VIN). The incidence of both warts and VIN has been shown to be reduced dramatically in vaccinated populations. Genital warts are usually small warty papules but they may become confluent and can be very widespread in immunosuppressed patients. Treatments involve cryotherapy, imiquimod, or surgical ablation.

Intra‐epithelial neoplasia

There are two pathways to the development of malignancy on the genital skin. The most common type is related to the oncogenic types of HPV, mainly 16 and 18, which can cause cellular changes leading to VIN or penile intra‐epithelial neoplasia (PeIN). Known risk factors are immunosuppression and smoking. Several terms have been used to describe this previously such as Bowenoid papulosis, erythroplasia of Queyrat, etc. These terms should no longer be used. In females, the term high risk squamous intra‐epithelial lesion has recently been introduced.

The lesions of HPV‐associated intra‐epithelial neoplasia are often polymorphic in appearance, ranging from flat pigmented macules to widespread erythematous and warty hyperkeratotic plaques (Figure 21.11). They are sometimes unifocal, but more commonly multifocal and similar changes can be found in the vagina, cervix, and perianal skin (Figure 21.12). These areas should be examined routinely, and management of these patients needs a multidisciplinary approach with gynaecologists, urologists, and colo‐rectal surgeons.

Figure 21.11 Vulval intra‐epithelial neoplasia with white hyperkeratotic plaques.

Figure 21.12 Perianal HPV‐associated intra‐epithelial neoplasia.

Treatments includes surgery for smaller unifocal lesions or medical treatment for larger multifocal areas with 5% imiquimod. Patients should be referred to a specialist clinic.

The second pathway is the development of malignancy on a background of a chronic inflammatory disorder such as lichen sclerosus or LP. This is much less common and differentiated VIN or PeIN may be seen initially, but this may be difficult to diagnose histologically and very clear clinico‐pathological correlation is vital. These patients usually have atypical clinical features with hyperkeratosis and erosions and do not respond to treatment as well as those with uncomplicated disease. There are subtle changes at the basal layer but the rest of the epidermis is differentiating normally. There is a very high risk of those with differentiated VIN or PeIN progressing to an invasive SCC and these lesions should always be excised.

Extra‐mammary paget’s disease

Paget’s disease is an in situ adenocarcinoma and disease of the nipple is well known. The genital area is the most common site involved with extra‐mammary Paget’s disease (EMP) and although rare, affects females much more than males. It usually occurs in the elderly and the diagnosis is often delayed so that patients may have extensive disease at presentation.

The clinical appearance is that of erythematous moist plaques which can mimic other inflammatory dermatoses. However, the plaques are often asymmetrical and in patients where a clinical diagnosis of psoriasis is made but who do not respond to treatment, there should be a low threshold for biopsy.

Histology is diagnostic but clinico‐pathological correlation is important as the histological differential diagnosis includes Bowen's disease and melanoma. Specific immunohistochemistry shows cytokeratin 7 and 20, but negative S100.

In contrast to mammary Paget's, which has a very high risk of associated breast cancer, only about 20% of patients with EMP will have an associated neoplasm which may involve the genital, gastrointestinal, or renal tracts. Investigation for this should be undertaken when EMP is diagnosed.

The treatment is challenging as disease is often extensive and recurrence rates with surgery, even with reported clear margins, can be up to 60%. Topical 5% imiquimod can be extremely useful in these patients if tolerated. Radiotherapy and photodynamic therapy are alternatives.

Vulval and penile pain

Patients with conditions that erode, fissure, or ulcerate will present with pain and appropriate treatment for the underlying problem should resolve the symptoms. However, neuropathic pain can affect the genitalia where the skin looks normal and there is nothing seen to explain the symptoms of burning, discomfort, and pain. Itch is not a symptom. This has been studied more in females than males where it is termed vulvodynia. This is defined as ‘pain in the vulva of more than three months duration with no obvious inflammatory, infective, or neurological cause’.

There are two classic symptom patterns but there may be overlap between the two in some patients.

- Localised provoked vulval pain – These patients are usually young, with a gradual onset of pain with pressure on the vulva i.e. with sexual intercourse or inserting tampons. Wearing tight clothing or touching the area gives a similar pain. Removing the pressure resolves the pain. Most women localise the symptoms to the vestibule, hence the term ‘vestibulodynia’. The diagnosis can be confirmed by touching the vestibule with a cotton tip where the symptoms are easily reproduced.

- Generalised spontaneous vulval pain – These patients tend to be older and the pain is generalised affecting the whole vulva and is often constant although may fluctuate in severity. It may radiate to the buttocks and thighs. There are no provoking factors.

In both groups, there is a strong association with other conditions including irritable bladder, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, migraine, and temporo‐mandibular joint dysfunction.

Treatment should be targeted at the neuropathic nature of the problem and involves local anaesthetic preparations, nerve modulating agents e.g. tricyclics, gabapentin. Expert physiotherapy can be helpful for those with secondary vaginismus.

Further reading

- Bunker, C.B. and Porter, W.M. (2016). Dermatoses of the male genitalia. In: Rook's Textbook of Dermatology, 9e (ed. C.M. Griffiths, J. Barker, T. Bleiker, et al.). Chichester: Wiley‐Blackwell.

- Lewis, F.M., Bogliatto, F., and van Beurden, M. (2016). A Practical Guide to Vulval Disease – Diagnosis and Management. Wiley‐Blackwell.

- Lewis, F.M., Tatnall, F.M., Velangi, S.S. et al. (2018). British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus, 2018. British Journal of Dermatology 178 (4): 839–853.