CHAPTER FOUR

A DREAM IN WHICH THERE’S A LOT OF RUNNING

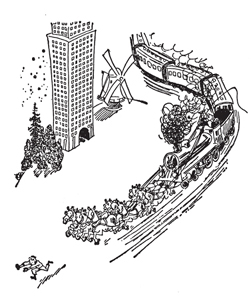

SUDDENLY EMIL HAD THE FEELING THAT THE TRAIN WAS going in spirals, like the toy train sets that kids play with in their rooms. He looked out the window and found it all very strange. The spiral kept getting smaller. The engine kept coming closer to the caboose, and it looked like it was doing it on purpose! The train was running in circles like a dog trying to bite its own tail. And there in the middle of that furious black circle stood trees and a windmill made of glass and a towering skyscraper two hundred floors high.

Emil wanted to check the time and started to take his watch out of his pocket. He pulled and pulled on the chain, but what came out was Mom’s grandfather clock from the living room. He looked at the face and the time read “115 miles per hour. Danger! Spitting on the floor prohibited on penalty of death!” He looked out the window again. The engine was drawing even closer to the caboose. And he was terrified, because if the engine ran into the caboose there would be a train wreck. That much was clear. And Emil had no interest in waiting around until it happened. He opened the door and ran down the sideboard. Maybe the engineer had fallen asleep? Emil peered into the compartment windows as he clambered forward. There was no one inside. The train was empty. Emil saw only one person, a man with a bowler hat made of chocolate. The man broke off part of the brim and ate it. Emil knocked on his window and pointed at the engine. But the man only laughed, broke off another piece of chocolate, and rubbed his belly because it tasted so good.

Finally Emil made it to the coal car. He nimbly monkey-barred his way up to the engineer, who was sitting on a coach seat, brandishing his whip and holding the reins as if the train were being pulled by a team of horses. And as a matter of fact, it was! Three rows of three horses each were pulling the train. They had silver rollerskates on their hoofs and were gliding on them down the rails, singing, “M errily merrily merrily merrily, life is but a dream.”

Emil shook the coachman and shouted, “Pull up the horses! We’re about to crash!” Then he saw that the coachman was none other than Officer Jeschke. The man glared at him and yelled, “Who were the other boys? Who defaced the Grand Duke?”

“I did it!” said Emil.

“Who else?”

“I’m not saying!”

“Then we’ll just have to keep going in circles!”

Officer Jeschke cracked the whip so that his horses reared up and took off even faster than before after the caboose. And there at the back of the caboose was Mrs. Jacob, waving her shoes around, visibly terrified of the horses, who were snapping at her toes.

“I’ll give you twenty marks, Officer Jeschke!” cried Emil. “Pipe down, will you!” shouted Jeschke and began whipping his horses like a madman.

Emil couldn’t take it any longer and jumped off the train. He turned twenty somersaults down the hill, but made it without a scratch. He stood up and looked around for the train. While he was standing there like that, all nine horses turned their heads toward him. Officer Jeschke had jumped up and was thrashing them with his whip, roaring, “Giddy up! Follow him!” The horses leaped off the rails and charged at Emil, the cars bouncing after them like rubber balls.

Emil didn’t stop to think, he simply ran off as fast as his legs could carry him. Across a field, past a great number of trees, and through a creek toward the skyscraper. Now and then he looked back. The train thundered after him without letting up. It flattened the trees and broke them to splinters. Only one tree, an enormous oak, was left standing, and there in its highest branches sat fat Mrs. Jacob, swaying in the wind, crying and trying in vain to get her shoe back on. Emil kept running.

The two-hundred-floor-high skyscraper had a large, black door. He ran in it and through the building and out the other side. The train came after him. Emil would have liked nothing more than to sit down in a corner and fall asleep, he was so awfully tired, his whole body was shaking with exhaustion. But he couldn’t doze off! The train was already clattering through the skyscraper.

Emil saw an iron ladder running up the side of the skyscraper to the top. He started climbing up. Luckily he was a good athlete. As he was climbing, he counted the floors. At the fiftieth floor he actually turned and looked down. The trees had gotten extremely small, and the glass windmill was hardly recognizable. But—no! The train was driving up the side of the building! Emil kept climbing higher and higher. And the train stomped and roared up the ladder as if it were a train track.

The 100th floor, the 120th floor, 140th, 160th, 180th, the 200th floor! Emil stood on the roof and had no idea what he should do next. He could already hear the horses’ neighing. So the boy ran across the roof to the opposite end, pulled his handkerchief from his suit, and unfolded it. And just as the sweating horses came climbing over the parapet with the train in tow, Emil held his unfurled handkerchief over his head and jumped off. He heard the train knocking over the chimneys behind him. Then for a while he neither heard nor saw anything at all.

And then he landed with a thud. Boom! He was in a field.

At first he just lay there, exhausted, his eyes closed, and wanted nothing more than to drift into a pleasant dream. But he didn’t feel entirely safe yet, so he looked up at the skyscraper and saw the nine horses up on top opening umbrellas. Officer Jeschke had an umbrella, too, and was using it to prod the horses. They sat up on their hind legs, hopped forward a little, and jumped into the air. And now the train was sailing down toward the field, growing larger and larger.

Emil jumped to his feet again and took off across the field toward the glass windmill. It was translucent, and he saw his mother inside, shampooing Mrs. Augustin’s hair. Thank God, he thought, and ran into the windmill through the back door.

“Mom!” he yelled. “What should I do?”

“What’s wrong, dear?” his mother asked, and went on shampooing.

“Look out the wall!”

Mrs. Tabletoe looked out and saw the horses and train land on the field and charge off toward the windmill.

“Why, it’s Officer Jeschke,” said Emil’s mom, and shook her head in amazement.

“He’s been racing after me like a madman all day!”

“Is that so?”

“A few days ago I was on the main square, and I painted a red nose and a moustache on the face of Grand Duke Charles with the crooked cheek.”

“Well, where else where you supposed to put the moustache?” said Mrs. Augustin with a snort.

“Nowhere, Mrs. Augustin. But that’s not the worst of it. He wanted to know who else was there with me. But I can’t tell him that. It’s a question of honor.”

“Emil’s got a point,” said his mother. “But what do we do now?”

“Why not simply turn on the motor, Mrs. Tabletoe?” said Mrs. Augustin.

Emil’s mom pulled down a lever on the table, and the windmill’s four sails began to turn. Because they were made of glass and the sun was shining, they gleamed and shimmered so much that you could hardly look at them. When the nine horses and their train came running up, they got spooked, reared up on their hind legs, and refused to go a step further. Officer Jeschke swore so loudly you could hear it through the glass walls. But the horses wouldn’t budge.

“There. Now would you please continue shampooing my scalp?” said Mrs. Augustin, “Your boy has nothing to worry about now.”

So Mrs. Tabletoe the hairdresser got back to work. Emil sat down on a chair, which was made of glass as well, and let out a whistle. Then he laughed and said, “Well that’s just great. If I’d known you were here, I wouldn’t have bothered climbing up that darn skyscraper.”

“I hope you didn’t tear your suit!” said his mom.

Then she asked, “Did you keep your eye on the money?”

At that, Emil felt a sudden jolt and fell off the glass chair with a loud crash.

And woke up.