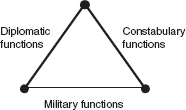

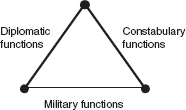

In collective imaginaries, navies are constructed as ‘powerful’, ‘prestigious’ and ‘grand’. From the works of Dutch painters in the seventeenth century glorifying naval battles to the romantic literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries glorifying British seapower, artistic and literary representations of the navy have centred on big warships or armadas of ships in action.1 Whereas such representations highlight the historical heroism of navies and sailors, they also contribute to emphasising the primacy of ‘big navies’ when it comes to balance of power and fulfilling national interest and foreign and defence policy objectives.2 Assessed against the triangle of naval missions developed by Ken Booth and revisited by Eric Grove, ‘small navies’ appear to be lacking in scope and capacity (see Figure 3.1).3

Indeed, when it comes to military/combat missions (e.g. sea control, power projection) as well as diplomatic missions (e.g. forward presence), ‘small navies’ appear to be reduced to a limited and/or coastal role; and their main function seems to be limited to the constabulary one (e.g. policing territorial waters). This can be attributed to their lack of ocean-going capabilities and firepower, the limited number and size of platforms, as well as the resulting lack of operational experience and even maritime culture. The constabulary function has traditionally been considered in a rather negative or contemptuous way by navies themselves.4 Although this perception has recently started to change, this has nevertheless contributed to representing ‘small navies’ in a derogatory way relative to the prestigious ‘big navies’ engaged in naval battles or power projection.

Figure 3.1 Triangle of naval missions.

Source: c.f. footnote 3.

Against this background, the aim of this chapter is to revisit this ‘misfortune of small navies’ by framing the analysis within the concept of seapower rather than naval missions, with the aim to show that ‘small navies’ can actually be depositories of seapower, albeit not exactly in the same form as ‘big navies’. First, this chapter will show that the traditional conception of seapower has contributed to a naval pecking order placing ‘small navies’ at the bottom of the hierarchy. Second, it will demonstrate that post-modern seapower must be understood as a collective form of power and governance that extends far beyond naval/military considerations. Within this context, a naval hierarchy along a ‘big’/’small’ binary loses relevance both as an indicator of seapower and as a way to represent navies in the twenty-first century.

The Mahanian conception still dominates narratives on seapower. Mahan advocated seapower as a way to positively ‘exercise effects […] upon the welfare of the people’.5 Accordingly, states shall aim at developing a ‘powerful navy’, which is instrumental in gaining command of the sea and protecting maritime trade. In other words, seapower rests on ‘the connection between a flourishing maritime trade that generates the nation’s wealth and a powerful navy to protect it’.6 Such a conception has informed generations of decision-makers who engaged their country in navalist policies, from Theodore Roosevelt’s US to Sergei Gorshkov’s Soviet Navy to China in the twenty-first century.7

Beyond Mahanian navalist policies, navies must indeed be understood as the main vector of seapower, at least in its naval acceptation. During the Cold War, the East–West arms race had an important naval component, which has led to the adoption of ‘big to be powerful’ narratives, e.g. balanced fleet; 600-ship navy.8 With the end of the Cold War, the traditional mission consisting in gaining command of the sea (potentially following a decisive naval battle) has lost prominence in favour of an emphasis put on exercising command in the form of power projection, which de facto became the ‘grand’ mission of navies.9 Since the 1991 Gulf War, the media representation of war has contributed to certain images gaining an ‘iconic’ status, such as green nightscape or missiles fired from ships.10 This glorification of power projection missions via visual representations has in turn strengthened the primacy of ‘big navies’ in collective imaginaries.

All of the above has contributed to the establishment and consolidation of a naval pecking order; a process of ‘othering’ (i.e. big versus small), or in other words a hierarchisation of navies.11 Such a categorisation proceeds from a classical syllogism: (1) ‘Big navies’ are powerful whereas ‘small navies’ are less powerful, (2) It is better to be powerful, so (3) ‘Big navies’ are better than ‘small navies’. In this process, what counts seems to be the position of each navy relative to others, rather than each navy’s individual capacities judged against their state’s needs and defence objectives. Quantitative indicators, such as order of battle, naval budget and manpower, and qualitative indicators, such as global reach, endurance and ‘order of effects’12 contribute to such a hierarchisation. It is always possible to move up (or down) the hierarchical ladder, but the naval pecking order has actually not evolved a lot since the end of the Second World War, with the US topping the league tables, followed by Russia/USSR, the UK and France.13 At the top of the hierarchy, China’s growing naval capability is probably the most striking evolution of the past decades. The outcome of such a representation and categorisation is that ‘big navies’ are the depository of seapower (understood as naval power) and can exert it, whereas ‘small navies’ are seemingly destined to live in the shadow of ‘big navies’ and to remain footnotes in (naval) history.

‘Small navies’ can overcome their ‘misfortune’ by participating in multinational coalition operations or exercises. This has become one of the main if not the primary objective of many ‘small navies’. In the Irish 2011–2014 Strategy Statement, the ability to operate with ‘like-minded states’ had even been labelled as a key performance indicator of the armed forces.14 The participation of Canada’s HMCS Charlottetown in NATO operations against Gadhafi’s Libya in 2011 has been praised in both media and official documents for it was the first time since the Korean War that the Canadian Navy had been under enemy fire.15 Often, small navies’ material contribution to such coalition operations remains very limited, but the symbolic effort is nonetheless valuable: to ‘express solidarity with our friends’.16 Small navies can thus exercise a form of extrinsic power by being ‘part of the great game’, not in terms of intrinsic contribution but by the mere fact that they ‘are there’, in operation, which sends two different but related political messages: to allies ‘you can count on us’ and to domestic and third-party audiences ‘we can do it’. From a capacity-building perspective, participating in multinational naval operations constitutes a real opportunity to ‘learn by doing’, to test interoperability standards and to drill joint/combined procedures in operational conditions. Also, being part of standing coalitions or forces, in particular within NATO, allows small countries to be part of the process of setting up the rules of the game at sea, to ‘have a voice’,17 albeit without a strong power of influence within the coalition itself.

However, this strategy is not without potential downsides. There is a risk of ‘entrapment’, meaning that small navies can be dragged into participating in operations that have been decided by, and that are primarily in the interest of, other big powers.18 There is also a risk of role specialisation (e.g. Baltic navies with mine countermeasures), which may be achieved at the expense of other useful capabilities; this is all the more important given the volatile post-Cold War security context that requires naval forces to operate in various environments and at various scales and to engage in several crises at a time, which makes naval planning more difficult for states with limited resources.19 Small navies may also become dependent on senior partners in terms of critical information sharing, especially in the context of network-centric warfare;20 in other words, interoperability is not only a technical challenge, it is also about ‘political will’.21 Even if those risks and issues are eventually minimal, ‘small navies’ cannot be said to exercise substantial naval power and authority when participating in multilateral naval operations as junior partners and thus this does not modify the perception discussed above that they are not depository of seapower understood as naval power.

The dominant Mahanian conception of seapower is framed within a political realist, modern understanding of security, where the referent objects are states and their agents, in particular military forces including navies. With the expansion of the security agenda following the end of the Cold War, seapower has stopped being primarily, or at least exclusively, associated with naval power. Indeed, the growing importance placed on non-state actors and transnational threats has led seapower to adopt a post-Mahanian, post-modern outlook.22 This conception is less state-centric and less biased towards the military dimension of seapower.

There is indeed an overlooked form of non-military seapower, which is about maintaining good order at sea and stabilising the liberal world order in the maritime domain. Ocean governance aims to steward marine resources and organise maritime spaces in a way that enables various state and non-state stakeholders to operate under optimal conditions, which also include maritime security operations. This necessitates regulating, organising and monitoring human activities and flows of goods and people at or from the sea, and responding to forms of criminality that include illegal fishing, piracy, drug and arms smuggling and human trafficking. Given the nature of the maritime domain, which is a space that, unlike the land, cannot be occupied or even owned,23 is hard to monitor and transnational by nature with fuzzy borders, ocean governance and maritime security require international, transnational and multilevel cooperation, leading to a form of collective seapower. Post-modern seapower implies a territorialisation of the sea via marine spatial planning, maritime surveillance, zonation etc. Such a stabilisation of the liberal world order at sea requires multinational cooperation at various levels much beyond naval considerations. Geoffrey Till claimed that seapower is relative ‘since some countries have more than others’.24 Whereas this reflects the modern understanding of seapower, the argument here is that seapower can now be absolute when it comes to ocean governance and stabilisation/maritime security. It can indeed be enacted in a joint way and the benefits of its enactment can be shared and are not mutually exclusive. In other words, the enactment and consequences (or outputs in Till’s words25) of post-modern seapower is not framed within a zero-sum game. Various state and non-state stakeholders contribute to this form of post-modern seapower and benefit from it in very different ways and not in equal shares. For example, efforts to limit piracy at the Horn of Africa have cost and benefited Western states, international shipping companies, regional states and local communities in a very different way.26

Within this post-modern framework, the position and role of ‘small navies’ are very different: their constabulary function, which consists in policing the sea to monitor and repress illegal activities within and beyond territorial waters, is valued, not only at a national level but at the global level too. When in the mid-noughties the US launched the concept of 1000-ship navy, it was based on the realisation that it was not possible to stabilise and control the maritime domain without the positive participation of every possible state and relevant private stakeholder sharing similar objectives.27 This clearly includes ‘small navies’. Whereas the concept, which was rebranded Global Maritime Partnership, encountered some negative feedback,28 this is nonetheless a demonstration of the need to account for the existence of a non-Mahanian form of seapower along with the more traditional, naval one. Post-modern seapower does not require every participating state and stakeholder to think and be the same, nor to share similar international politics objectives. It is best understood within the concept and practice of a pluralistic international society, developed by scholars of the English School of International Relations to describe the existence of a society of states, which share the common desire to maintain a certain degree of order, stability and certainty within the international system without systematically sharing similar values and identities.29 At sea, this translates into a common belief in the freedom of the seas and in the need to maintain a reasonable level of order and security in the maritime domain so as to benefit from the advantages that freedom of the seas grants states and economic agents. Post-modern seapower is thus inherently liberal, but a form of liberalism that is limited in scope and ambition and constrained by domestic considerations. For example, the ongoing migrant crisis in the Mediterranean illustrates the importance for states to devote enough resources to constabulary missions, for which ‘small navies’ or coastguards are well prepared. Interestingly, the current issues with the management of the crisis show that when not enough resources are devoted to ocean governance, then the non-governmental sector steps in, as illustrated by the involvement of private/NGO rescue vessels.30

An interesting example beyond Europe and NATO members is the case of Singapore; a small country that depends on the freedom of the seas for its economic performance and thus understands that it needs to be integrated within the global effort to secure the seas,31 since it will eventually benefit from it as well:

[The Republic of Singapore Navy forms] a vanguard against sea robberies, piracy, terrorism and unwanted incursions […]. We are not just a fighting force […]. We sail across the seas, exercising with other navies and visit foreign ports. We take part in international operations for peace support, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. By co-operating with like-minded nations and being a responsible member of the international community, the RSN is able to not just defend our nation’s every day, but also the world’s every day.32

This quotation epitomises the collective form of seapower discussed above, where every stakeholder, whatever their size and capabilities, are in a position to contribute to the global effort to secure the seas, knowing that the stabilisation of the global liberal order at sea is in their best interest in absolute if not in relative terms. In another example, the Royal New Zealand Navy’s participation in multinational operations aiming at securing sea lanes of communications, such as NATO counter-piracy operation Ocean Shield at the Horn of Africa, has been described as a contribution to the country’s ‘role as a good global citizen’.33 Since New Zealand is itself strongly dependent on the sea and ‘has one of the largest exclusive economic zones in the world’34 (prone to forms of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing), this also illustrates the non-zero sum nature of post-modern seapower.

This does not mean that in the context of global ocean governance states always act in a purely benevolent way; participation (or indeed non-participation) in global maritime security efforts may well proceed from domestic political considerations or be linked to specific power maximisation interests.35 In other words, the existence of a collective form of seapower does not imply that enacting it is the default policy option. If an issue is deemed sensitive in terms of national interest, including commercial interests, then global ocean governance may not be chosen as the preferred option, whereas the management of low-politics and benign issues is less likely to generate negative reactions. Similarly, bureaucracies, such as navies, may be reluctant to share information especially in the case of sensitive data and of civilian-military cooperation, with explanatory factors ranging from mistrust over motives and policy interests, to bureaucratic competition/self-interest, to divergent organisational culture, to fear that new cooperative arrangements may jeopardise previous investments, to fear of dependency, exploitation and even survival.36 Mitchell stresses that ‘policy barriers hinder allies, even close ones, from sharing information with each other transparently’.37 It is also important to understand that the current main global maritime security cooperation initiatives are often de facto led by the US Navy. Consequently, the willingness or reluctance to engage in such forms of cooperation depends on an individual state’s and navy’s perception of the US power and goals in relation to their own interests, objectives and strategic realities.38

Post-modern seapower is conceived as a collective effort with shared benefits, rather than a zero-sum game. Ocean governance and maritime security are key elements of post-modern seapower, since they necessitate collective action aiming at controlling the maritime domain. ‘Small navies’ are depository of post-modern seapower understood in its non-state centric, collective and absolute acceptation. They constitute a useful and integral part of the effort to project security, stability, order and norms beyond one’s external boundary/territorial waters, in a bid to control the flows of goods and people across the maritime domain. Even though collective seapower is by no means the default policy option and is but one form of maritime power along with more traditional, modern, naval power, a hierarchy along binary oppositions has lost relevance as an indicator of seapower and as a way to accurately represent navies in the twenty-first century context.

The implications for seapower studies are twofold: a) scholars interested in seapower are encouraged to think beyond naval missions and material capabilities; seapower is not restricted to naval power or to the protection of maritime trade and navies are not limited to being vectors of naval power; b) more attention shall be placed on civilian aspects of seapower, and there is a collective dimension of seapower that shall not be neglected. In sum, post-modern seapower is collective, mostly liberal and not state-centric; it is focused on the governance of the maritime domain.

There are also implications for the study of ‘small navies’. This chapter has shown that ‘small navies’ are undeniably relevant naval agents to study, beyond naval multilateralism and naval coalition operations. Wartime operations or military interventions do not operationally require the participation of ‘small navies’ beyond the political or symbolic element of it. However, contributing to maritime security in particular and ocean governance in general, which is a peacetime task, constitutes an important contribution to stability and order at sea, one that requires every state and concerned stakeholder to participate at various scales. In other words, the agency of ‘small navies’ in global ocean governance shall not be neglected. Small navies remain ‘small’, but they are ‘powerful’ in that they exert and benefit from seapower in its collective, post-modern acceptation.

1 Samuel Baker, Written on the Water: British Romanticism and the Maritime Empire of Culture (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2010); Tricia Cusack, ‘Introduction: Framing the ocean, 1700 to the present: envisaging the sea as social space’ in Framing the Ocean, 1700 to the Present, Envisaging the Sea as Social Space, ed. Tricia Cusack (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014); John C. Mack, The Sea: A Cultural History (London: Reaktion, 2011), 1–22.

2 For a critical discussion of the definition of ‘big’ and ‘small’ navies, see Geoffrey Till ‘Are Small Navies Different?’ in Small Navies, eds. Michael Mulqueen, Deborah Sanders and Ian Speller (Farnham: Ashgate – Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies Series, 2014), 21–31.

3 Ken Booth, Navies and Foreign Policy (New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1979), 15–25; Eric Grove, The Future of Sea Power (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1990), 234.

4 Michel d’Oléon, ‘Policing the Seas: The Way Ahead’ in The Role of European Naval Forces after the Cold War, ed. Gert de Nooy (The Hague, London, Boston: Kluwer Law International, 1996), 143.

5 Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783 (New York: Cosimo Classics, 2007), 89, original edition (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1890).

6 Basil Germond, The Maritime Dimension of European Security: Seapower and the European Union (London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 5.

7 Sergueï Georgi Gorshkov, The Sea Power of the State, 1st edn (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1979, original edition Moscow: Voenizdat, 1976); James R. Holmes and Toshi Yoshihara, Chinese Naval Strategy: The Turn to Mahan (Abingdon: Routledge, 2008); Peter Karsten, ‘The Nature of “Influence”: Roosevelt, Mahan and the Concept of Sea Power’ American Quarterly 23, no. 4 (1971): 585–600; Kevin Rowlands, ed. 21st Century Gorshkov: The Challenge of Sea Power in the Modern Era (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2017).

8 On the 600-ship Navy, see John B. Hattendorf, ed. The Evolution of the U.S. Navy’s Maritime Strategy, 1977–1986 (Newport RI: Naval War College Newport Papers no. 19, 2004).

9 Germond, The Maritime Dimension of European Security, 51–72.

10 Andrew Hoskins, Televising War: From Vietnam to Iraq (London and New York: Continuum, 2004), 23–27, 30.

11 Basil Germond, ‘Small Navies in Perspective: Deconstructing the Hierarchy of Naval Forces’ in Small Navies eds. Mulqueen et al. (Farnham: Ashgate – Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies Series, 2014), 33–50; see also Captain (N) L.M. Hickey, ‘Enhancing the Naval Mandate for Law Enforcement: Hot Pursuit or Hot Potato?’ Canadian Military Journal 7, no. 1 (2006): 46; Aaron P. Jackson, ‘Keystone Doctrine Development in Five Commonwealth Navies: A Comparative Perspective’ Papers in Australian Maritime Affairs 33 (2010): 12; Harold J. Kearsley, Maritime Power and the Twenty-First Century, (Aldershot: Dartmouth Publishing Co. Ltd., 1992), 175 quoted in Michael S. Lindberg, Geographical Impact on Coastal Defence Navies (Basingstoke Macmillan, 1998), 32.

12 See Julian Lindley-French and Wouter van Straten, ‘Exploiting the Value of Small Navies: The Experience of the Royal Netherlands Navy’ The RUSI Journal 153, no. 6 (2008): 67.

13 For a quantitative comparison of naval forces since 1961, see The Military Balance (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies (published yearly); for a league table comparison demonstrating a certain inertia of the hierarchy, compare Eric Grove, The Future of Sea Power (Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press, 1990), 236–240 with Eric Grove, ‘The Ranking of Smaller Navies Revisited’ in Small Navies, eds. Mulqueen et al. (Farnham: Ashgate – Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies Series, 2014), 15–20.

14 Department of Defence Ireland, Strategy Statement 2011–2014 (Co. Kildare: DoD, 2011), 33.

15 For example, see ‘Canada’s military contribution in Libya’ CBC News, 20 October 2011, www.cbc.ca/news/world/canada-s-military-contribution-in-libya-1.996755 (accessed 25 June 2018); Peter Pigott, ‘Taking a stand: inside Operation Mobile’ Wings, 21 January 2012, www.wingsmagazine.com/operations/taking-a-stand-inside-operation-mobile-6498 (accessed 25 June 2018); National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces, ‘ARCHIVED – Operation MOBILE’ last modified 22 January 2014, www.forces.gc.ca/en/operations-abroad-past/op-mobile.page (accessed 25 June 2018); interestingly, the Wikipedia page for Operation Mobile even states that this operation constitutes Canada’s first ‘naval battle’ since the Korean War, accessed 25 June 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Mobile.

16 Royal Canadian Navy, ‘Leadmark 2050: Canada in a New Maritime World’ (2017, accessed 25 June 2018), 13, http://navy-marine.forces.gc.ca/assets/NAVY_Internet/docs/en/analysis/rcn-leadmark-2050_march-2017.pdf.

17 Philippe Lagassé, ‘Specialization and the Canadian forces’ Defence and Peace Economics 16, no. 3, (2005): 210.

18 On entrapment, see Glenn H. Snyder, ‘The Security Dilemma in Alliance Politics’ World Politics 36, no. 4 (1984): 461–495; for a critical discussion, see Tongfi Kim, ‘Why Alliances Entangle But Seldom Entrap States’ Security Studies 20, no. 3 (2011): 350–77.

19 Norman Friedman, ‘Transformation and Technology for Medium Navies’ Canadian Naval Review 2, no. 2, (2006): 5–11.

20 Paul T. Mitchell, ‘Small navies and network-centric warfare: Is there a role’ Naval War College Review 56, no. 2 (2003): 83–99.

21 Kenneth Gause, Catherine Lea, Daniel Whiteneck and Eric Thompson, ‘U.S. Navy Interoperability with its High-End Allies’ Center for Strategic Studies, Center for Naval Analyses, 2000, www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a468332.pdf (accessed 10 September 2018); see also Paul T. Mitchell, ‘International Anarchy and Military Cooperation’ The Adelphi Papers 46, no. 385 (2006): 45–52.

22 For pioneering discussions of such a move, see Michael Pugh, ‘Is Mahan Still Alive? State Naval Power in the International System’ The Journal of Conflict Studies 16, no. 2 (1996): 109–23; Geoffrey Till, ‘Maritime Strategy in a Globalizing World’ Orbis 51, no. 4 (2007): 569–575.

23 On the debate about the ownership of the seas, see Monica Brito Vieira, ‘Mare Liberum vs. Mare Clausum: Grotius, Freitas, and Selden’s Debate on Dominion over the Seas’ Journal of the History of Ideas 64, no. 3 (2003): 361–77.

24 Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A guide for the 21st century (4th edn Abingdon, UK: Routledge 2018), 4.

25 Till, Seapower, 4–6.

26 On the economics of piracy and counter-piracy, see Giacomo Morabito, ‘Maritime Piracy: Beyond Economic Concerns and Private Business Interests’ Georgetown Journal of International Affairs 18, no. 1 (2017): 43–46; Anja Shortland, ‘Dangers of Success: The Economics of Somali Piracy’ in Militarised Responses to Transnational Organised Crime, eds. Tuesday Reitano, Sasha Jesperson and Lucia Bird Ruiz- Benitez de Lugo (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 169–185.

27 See, for example, Admiral Michael Mullen, ‘What I Believe: Eight Tenets That Guide My Vision for the 21st Century Navy’ US Naval Institute Proceedings 132, no. 1 (2006, online version).

28 Geoffrey Till, ‘“A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower”: A View from Outside’ Naval War College Review 61, no. 2 (2008), 25–38.

29 Hedley Bull, The Anarchical Society: A study of order in world politics (London: Macmillan, 1977, reprinted 1995).

30 On the growing importance of non-governmental providers of SAR services, see Eugenio Cusumano, ‘Emptying the sea with a spoon? Non-governmental providers of migrants search and rescue in the Mediterranean’ Marine Policy 75 (2017): 91–98.

31 Joshua Ho, ‘Singapore and sea power’ in Sea Power and the Asia-Pacific: The Triumph of Neptune?, eds. Geoffrey Till and Patrick Bratton (London: Routledge, 2012), 130–143.

32 Republic of Singapore Navy, ‘Our Mission’ www.mindef.gov.sg/oms/navy/Our_Mission.HTM (accessed 6 July 2018).

33 Steven Paget, ‘The “best small nation navy in the world”? The twenty-first century Royal New Zealand Navy’ Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs 8, no. 3 (2016): 240.

34 Paget, ‘The “best small nation navy in the world”?’ 230.

35 Basil Germond and Michael E. Smith, ‘Re-thinking European security interests and the ESDP: Explaining the EU’s anti-piracy operation’ Contemporary Security Policy 30, no. 3 (2009): 573–93.

36 Graham T. Allison, Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis (Boston: Little Brown, 1971); Kevin Buterbaugh, ‘Making Trust or Breaking Trust: Cooperation and Conflict Between Organizations – The Case of the Active Services and National Guard’ Southeastern Political Review 27, no. 1 (1999): 129–150; Björn Fägersten, ‘Bureaucratic Resistance to International Intelligence Cooperation – The Case of Europol’ Intelligence and National Security 25, no. 4 (2010): 500–520; Hugo Slim, ‘Special Issue: Beyond the Emergency: Development within UN Peace Missions’ International Peacekeeping 3, no. 2 (1996): 123–140; James I. Walsh, ‘Intelligence-Sharing in the European Union: Institutions Are Not Enough’ Journal of Common Market Studies 44, no. 3 (2006): 625–643; Naomi Weinberger, ‘Civil-military coordination in peacebuilding: The Challenge in Afghanistan’ Journal of International Affairs 55, no. 2 (2002): 245–274.

37 Mitchell, ‘International Anarchy and Military Cooperation’ 46.

38 Geoffrey Till, ‘The New U.S. Maritime Strategy: Another View from Outside’ Naval War College Review 68, no. 4 (2015): 34–45.