Working with a new doctrine in a new

security environment

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and then of the Soviet Union in 1991, the direct military threat to Western Europe disappeared. For the Dutch authorities a new and unique security situation emerged. For the first time in its existence, the sovereignty or territory of The Netherlands was not threatened in any way. Shortly hereafter the government decided that the funds of the Dutch armed forces would steadfastly shrink and analyses were undertaken to decide what their future role would be. Gradually it became clear that the navy, army and air force had to change their focus from a general defence task to three main other missions. To wit: (1) defence of the Kingdom of The Netherlands, including the overseas territories in the Caribbean, as well as allied countries within NATO and the (West) EU; (2) protection and enforcement of the international rule of law; (3) assistance of civil authorities in and outside The Netherlands, including anti-terrorism, peacekeeping, disaster relief, etc.1

According to the new doctrine, published in the Royal Netherlands Navy (RNLN) white papers Leidraad maritiem optreden. De Bijdrage van het Commando Zeestrijdkrachten aan de Nederlandse Krijgsmacht (2005) and the updated Grondslagen van het maritieme optreden. Nederlandse maritime-militaire doctrine (2014), the navy adapted itself to these new tasks.

In the mentioned RNLN white papers it was explicitly stated that:

Naval vessels operated worldwide and focus more on the transport of military personnel and material then on waging battle at sea. […] The Dutch men-of-war also serve as floating bases for helicopters and landing craft. Furthermore, they are most suitable to fulfill a role as a center of logistic and/or a center of communication. The RNLN states that it can see action in both joint and combined operations.2

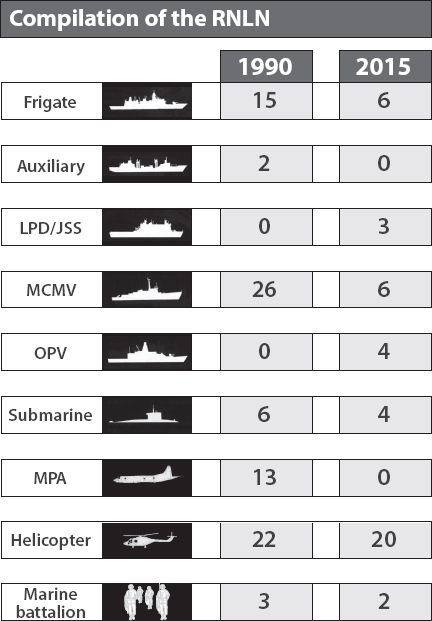

The RNLN, whose main role until 1989 was ASW in a blue water (coastal) environment, officially shifted its attention to brown water (in-shore) operations. Security from the sea was, especially after 2005, the new catch-phrase.3 This apparent change in focus, and growing financial restraint, undermined the capacity to fulfil this new role and simultaneously to undertake classic tasks in the field of sea control and sea denial.5 Also, the fleet changed both in size as well as in composition. The number of frigates decreased dramatically (from 15 to 6), both fleet tankers were sold, the squadron of long-range Maritime Patrol Aircraft (Lockheed P-3C Orion) was abolished and vessels like landing platform docks for operations of the Royal Netherlands Marine Corps (RNLMC), the army and air force, as well as lightly armed OPVs for constabulary tasks or serving as a station ship in the Dutch Caribbean territories, came into service.

Figure 8.1 Compilation RNLN 1990–2015.4

This chapter examines the evolution of the RNLN in the 25 years following the end of the Cold War by addressing five questions. First, it is analysed whether the kind of naval operations and doctrine after 1990 really differed from those in the period before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Second, what made the RNLN – which was relatively large if compared with smaller European navies like that of Ireland, Belgium or Denmark – have rather large ambitions? Third, why did the Dutch government on several occasions in the 1990s–early 2000s employ their navy as a tool of first solve as a response to international crises? Fourth, what influence did the RNLN have on Dutch foreign and security policy regarding these missions? And, finally, was the new naval doctrine from 2005, which was updated in February 2014, as well as the new composition of the fleet, the result of a new (inter)national security environment or budget cuts?

It is often suggested that after the Cold War many European navies had to change focus from operations in a blue water environment to that of a brown water environment. Of course, where necessary, in the 1990s, systems had to be adapted and the focus of some of the services had to be transferred. It is, however, a fact that even before the fall of the Berlin wall the RNLN had brown water NATO tasks. MCM operations in the North Sea, among others within the NATO framework of the maritime Standing Naval Force Channel (STANAVFORCHAN), mostly near to the coast, are an example of this, as was the engagement with British forces in the UK/Netherlands Landing Force, designed to support Norway and NATO’s northern flank from 1973 onward.

Furthermore, during out-of-area operations in the 1950s (Korea), and the 1980s (Middle East), the RNLN frequently saw action near the coast and in shallow waters. In addition, during the civil wars in former Yugoslavia, Dutch Maritime Patrol Aircraft and submarines (also) carried out classic ASW tasks. It is clear that the RNLN had undertaken a ‘mixture’ of tasks in the classic higher level of enforcement as well as more constabulary tasks in a brown and a blue water environment, both before and after the end of the Cold War.6

It was the Dutch admiralty that, after the loss of the last overseas territories East of Suez (West New Guinea) in late 1962, refused to confine the RNLN to a single ASW or (even worse in their eyes) MCM task in the grey and cold northern waters of NATO/eastern Atlantic area. They in no way wanted to see their navy transformed into ‘a small and confined continental navy’, as the Secretary of the Navy stated in 1963. Or, as a RNLN rear admiral publicly stated in 1985: ‘The Dutch navy has no area; all the free world oceans are our area operations.’7

Therefore, in the quarter century where NATO dominated Dutch defence planning (mid-1960s to 1990), the Dutch stuck to a doctrine of out-of-area reach as well as a sizable, for this broad purpose adjustable balanced fleet, consisting of cruisers, multipurpose/guided missile frigates/destroyers, submarines, Maritime Patrol Aircraft, MCM vessels and marines.8

Before the Second World War, the larger part of the Dutch navy was stationed in the Netherlands East Indies. This auxiliary squadron included 3–4 light cruisers, 25 destroyers and submarines, 24 minesweepers/layers, some motor torpedo boats and over 60 amphibious Maritime Patrol Aircraft. In 1939, the Dutch government, due to the threat of a Japanese invasion, also decided to construct two further light cruisers as well as three battle cruisers. Because of the Second World War and the German invasion in The Netherlands in May 1940 these (battle)cruisers never materialised.9

The Dutch admiralty was therefore no stranger to ambitious fleet plans. Influenced by negative experiences during the war, to wit: no or little influence on Allied maritime operations despite having a relatively large merchant fleet (fifth largest in the world) and participating in fighting operations until the war’s end with over a dozen men-of-war and numerous minesweepers, the RNLN in 1945 envisioned that, given the concept of sea power (and national influence), it had to strive for a flexible and balanced fleet that could fulfil a mixture of tasks. The admiralty exploited the political room for manoeuvre provided by huge national maritime prestige, especially in parliament. Also, given that the RNLN had its own and influential Minister of the Navy until 1971, the fact that the charming but cunning former naval captain and war hero Piet de Jong became Secretary of Defence (1963–1967) and later Prime Minister (1967–1971), and long-serving Minister of Foreign Affairs Joseph Luns (1952–1971) was zealously navy-minded, played into the hands of the Dutch admiralty. Further on, the RNLN in the 1950s made use of the weak position of the disorganised army, which had to reinvent itself after an inglorious retreat out of the lost colony Indonesia.10 In the early 1960s, at its height, the RNLN comprised of one aircraft carrier, two light cruisers, 22 destroyers and frigates, eight submarines, 72 minesweepers, 130 aircraft/helicopters and 4500 marines. After the French president Charles de Gaulle in 1963 pulled his naval forces out of the Allied Command Atlantic area, the Dutch were until the mid-1970s the third biggest NATO navy in the North Atlantic. Furthermore, the RNLN was one of the most proficient of the NATO navies in terms of ASW. National maritime pride of a major part of the population, as well as a relatively large shipbuilding and weapon systems industry until the mid-1980s, contributed therefore to a long-standing favourable stand of parliament towards the RNLN and its ambitions.11

For all these reasons; earlier global colonial responsibilities, the Second World War frustrations in having no say over the national (merchant) fleet, capable Ministers of the Navy, international standing and maritime jingoism of many politicians and voters, the Dutch navy could for decades live up to its huge ambitions. In this sense, the RNLN could, for a time, remain a medium-sized navy within NATO, with capabilities between those of larger navies such as the British and small allies like Belgium, Denmark, Norway and Portugal.12

One of the strategic multipliers in Dutch government foreign policy decisions was to observe good relations with the USA; the protector of its territory during the Cold War as well as the guardian of many of the Dutch overseas interests. Without entangling itself too much in the foreign policy ‘adventures’ of Washington, and becoming deeply involved in new ‘Vietnams’, different cabinets opted in the first phase of an international conflict for a maritime participation in a multinational enforcement mission, as with the response to Iranian minelaying in the Persian Gulf 1987–1988, the Gulf War of 1990–1991, the conflict in the former Yugoslavia 1992, Haiti 1993–1994 and after the 9/11 attack. For Dutch politicians, the fleet was an attractive political instrument, because the vessels were relatively quick to employ, but were also a tool of first resolve because the (long) period that they sailed to their area of operations left time for a political adjustment on the mission. With these maritime deployments, The Netherlands internationally gave a political signal, but simultaneously no major military, and therefore political, risks were taken. Furthermore, the ships could remain under national control because of the fact that they, in contrast to army units, were able to operate independently.13

The ability to demonstrate, both nationally and internationally, that the RNLN was a flexible organisation that could be employed worldwide at short notice upheld the prestige of the navy and proved useful at times when the budget was under threat. The RNLN used its out-of-area missions in the 1990s to illustrate that it was far more capable than the army and air force to fulfil these kinds of operations.

Demonstrating enthusiasm to participate in enforcement/embargo missions in the Middle East, the Adriatic or the Caribbean showed that the RNLN was able to operate worldwide together with larger Western navies like the US Navy and Royal Navy and to promote Dutch interests. With these kinds of operations, the RNLN was able to promote its prestige nationally and internationally, and could diminish the negative impact on the navy budget in the first decade after 1990. Remarkably, in these years, public remarks in the national media by flag officers and task force commanders succeeded in getting the government to change course in a direction favourable to the admiralty.14 Examples of this influence on Dutch politics include: extending the naval task force in the Persian Gulf in 1990 or operating under American and British command instead of being part of a European task force.15 Another is the broad and diverse presence of the RNLN in the Adriatic in the years 1992–1996 and 1999, by which the navy showed its own government that it could deliver a meaningful contribution in bringing the conflict in the former Yugoslavia to an end. This show of force helped to save the Submarine Service from liquidation and, for the short term, the squadron of Maritime Patrol Aircraft and some frigates. The same accounts for the operations after 9/11: from December 2001 onward, several frigates, submarines, as well as Maritime Patrol Aircraft, began their out-of-area anti-terrorism patrols in the Persian Gulf area in Operation Enduring Freedom.16

The earlier mentioned navy studies of 2005 and 2014, Leidraad Maritiem Optreden and Grondslagen van het maritiem optreden, continue to provide direction for the RNLN. Based on the study of 2005, three mayor strategic choices were made regarding thoughts on the navy.

First, the choice was made for task specialisation by operating in the Caribbean and in constabulary tasks.17 Six out of a class of eight multipurpose frigates were sold to create funds for OPVs.18 Unsuitable for service in enforcement or war situations, these lightly-armed vessels are more suitable for counter-drug and antipiracy operations.19

Second, cooperation with the Belgian navy was intensified. On the operational level, both navies were already working closely together, mostly regarding MCM-operations and with concern to additional education and logistics. Already in 1962, a binational MCM-school was set up in Oostend (éugermin, école de Guerres des Mines), of which in succession Dutch and Belgian officers were in command. Next to that, the Dutch cooperated with Belgian (and French) counterparts in the design of a new MCM vessel for the early 1980s (Tripartite project, current Alkmaar/Aster class). Also, under Belgian command, a binational MCM Task Group was sent to the Persian Gulf in 1987–1988. On the level of fleet command, there had also been a steady process of integration. In March 1975, a provisional Admiralty Benelux (Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg) was created for times of war.20 Partly because of shrinking naval assets, the two countries had decided in January 1996 that in peace time both operational naval staffs would be integrated into a single staff. Therefore, a new joint headquarters was set up in the Dutch naval base of Den Helder. From 2005 onwards, the Dutch Commandant Zeestrijdkrachten (C-ZSK) was also Admiral Benelux, with a Belgian flag officer as his deputy. Also, a joint School of Operations was created.21 Given these facts, it was no surprise that the navy white paper of 2014 was prepared in close cooperation with the Belgian navy.22 Furthermore, Belgium has since 2005 assumed responsibility for the instruction and training of Dutch and Belgian crews of MCM vessels as well as the logistics and maintenance of these ships. After the sale of two Dutch multipurpose frigates to Belgium (2005), The Netherlands has the same sort of obligations regarding Belgian M-frigates, their crews and helicopters. The four M-frigates are therefore mostly to be found in Den Helder and the MCM vessels vice versa in ports in Belgium. The integration of both navies is evolving even further with an integrated stand-by force.23 Moreover, both navies work closely together in future ship-building programs regarding new MCM vessels and the successor of the M-frigate.24

Apart from the strategic choice of intensifying the integration with the Belgian navy, over the last two years more cooperation has been sought with the German Bundesmarine, for example in funding and training with regard to the Joint Support Ship (JSS) Zr.Ms. Karel Doorman together with the German Seebatallion and Dutch marines. In 2016, it was announced that this new (2014) German unit (a naval protection force, mine-clearance divers and boarding teams) would be integrated into the RNLN during some exercises. They could learn, under Dutch command, from the experienced RNLMC.25 It was a rather innovative response of both countries to handle budget constraints. The RNLN, who earlier was only able to use the vessel with a reduced crew in merely a tanker and transport role, now saw possibilities to operate the JSS in exercises in a sea-basing role because of extra German sailors and equipment. The Bundesmarine could forgo the acquisition of costly JSS and build up much needed specialised expertise for their sailors and soldiers. The Netherlands for their part arranged that, whenever the Germans used the Karel Doorman, it in return could use tankers and supply ships of the Bundesmarine.26 In practice, however, the Dutch-German cooperation did not materialise, apart from one large-scale exercise in September 2018. Major problems with the main engines of the JSS during much of 2016–2017, as well as an unforeseen aid mission of the Karel Doorman in September–October 2017 to the Caribbean territories of the Kingdom, prevented earlier binational sea-basing exercises. Also, the sorry state of much of the German forces, including their tanker and supply vessels, in combination with rising Dutch naval budgets, raise some doubt over further close cooperation of the RNLN with the Bundesmarine.27

Last, but not least, the RNLN made the strategic choice to seek further integration of the fleet and RNLMC, to strengthen the maritime force and enhance the expeditionary capability and operational availability of the marines.28

In short, the naval operations and the vision on these missions shifted between 1990 and 2015 from control of large sea areas to maritime choke points (interdiction operations), and from SLoC to coastal/brown waters. More emphasis was therefore placed on MSOs, mostly outside (West) European waters.

The question remains, how far these developments were just a consequence of a changing security environment? In March 1991, the Dutch government presented the white paper Herstructurering en verkleining, followed in January 1993 by the Prioriteitennota: Een andere wereld, een andere Defensie. These two white papers were the basis for Dutch defence policy after the Cold War. All of the Dutch armed forces shifted their focus from a general, mainly collective European/North Atlantic defence task, to contributing actively in enhancing worldwide the international rule of law, and more tasks within the Kingdom of the Netherlands (including Caribbean territories) like anti-terrorism, with a meanwhile steadily decreasing defence budget. The latter development was ominously named: ‘to take in the Peace Dividend after the end of the Cold War’.29

In 2000 a new white paper followed, which focused even more on expeditionary and amphibious capabilities, but also on threats from North Africa and the Middle East with ballistic missiles. A second amphibious transport ship (Zr.Ms. Johan de Wit) after the Rotterdam in 1998, and four air defence frigates of the De Zeven Provinciën class, were therefore built. Also, a third marine battalion was foreseen.30

Meanwhile the Dutch armed forces shrank considerably. In 1990, the total number of military personnel was 111,000. In 2015, this was reduced to 42,000, of which less than 9000 were naval personnel. The defence budget went down from 2.4 per cent GNP to just above 1 per cent.31 For the navy, in the end, there was no escape. As earlier mentioned, the number of (mostly modern) frigates shrank from 15 to 6, from the 26 MCM vessels six were left, the Lockheed Orion P-3C Maritime Patrol Aircraft were sold in 2005 and the remaining navy helicopters came under the command of the Air Force. Also, after 350 years, a large part of the naval base of Amsterdam was closed.32 The third marine battalion never materialised and the Rotterdam marine barracks (the last military asset in the largest port of Europe) were only saved by co-funding of the municipality of Rotterdam, who stationed and trained hereafter specialised police units on these grounds.33 The last five years, operating costs of the shrinking fleet rose because of the fact that ships were ageing and repairs and docking time and maintenance took longer. Lack of spare parts, reduced participation in exercises, but also cuts in personnel (as well as a shortage of technical specialists), added to the fact that more and more vessels had to stay over a longer period in port.34 Amphibious operations took over from ASW. In 2015, the earlier-mentioned large amphibious JSS, the Karel Doorman (28,000 GRT), came into service.35

New budget cuts after 2010 meant that the fleet no longer had a specialised supply ship/tanker after Zr.Ms. Amsterdam was hastily sold to Peru in 2014. The JSS Karel Doorman, which would sail in the spring of 2015, could act as a supply vessel in addition to its primary role as an amphibious command ship, and had to take over all the tasks of the Amsterdam as well. A new supply ship/tanker to come into service in 2020 was cancelled due to a shortage of funds. It was a dear negative development for the RNLN but also for maritime European and NATO task forces, where there was and is a shortage of these kind of vessels.36

As mentioned earlier, for the RNLN in the 1990s, nothing seemed to change really that dramatically because of the earlier, traditional broad range of tasks and the balanced composure of the fleet. It still operated worldwide with an expeditionary focus, only with more emphasis on brown water operations. Nevertheless, after several rounds of reorganisation the other military branches became accustomed to structural involvement in expeditionary missions. The growing political will to participate in multinational peace keeping and peace enforcement operations, combined with a shrinking defence budget, meant that the navy, army and air force were working more and more together.37

These developments made the navy and the fleet vulnerable to further budget cuts. Especially so, because the main focus of these missions was on land operations (Ethiopia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Chad, Mali). Of the RNLN, the Marine Corps got most of the political attention. In 2005, the admiralty changed course in this regard, and as a result the marines got the same position as the operational services of the fleet. Previously the RNLMC, with a major general as Commandant, had a subordinate position to the Commandant der Zeemacht (Commander-in-Chief Fleet), a vice admiral, which also had a separate headquarters. Hereafter, fleet and marines were integrated, but on an equal footing. The RNLMC regained further influence by supplying the Commander of the whole RNLN (C-ZSK) by turn with the fleet. To wit: lieutenant-general Rob Zuiderwijk in 2007–2010 and lieutenant-general Rob Verkerk in 2013–2017. Furthermore the Commandant of the RNLMC occupied high command positions in the unified headquarters of the fleet and the marines; the Commandant was Director of Operations for the entire naval domain.38 Although the marines after 2009 drew most of the attention with their vessel protection detachments in antipiracy actions near Somalia, the fleet also profited from these (multinational) missions by escorting merchant ships and regaining with these operations good will amongst public and politicians. However, apart from proving that national men-of-war (submarines included) were indeed necessary for the protection of Dutch and befriended cargo vessels, the RNLN did not receive extra funding.39

Security from the sea, mostly expeditionary, was, as we concluded earlier, not a totally new phenomena for the RNLN, given the broad, worldwide and diverse tasks, doctrine and weapon platforms it had in the post-1945 decades. As a small European country with a large maritime heritage, prestige and industry, and a relatively large amount of seapower, factors that influenced over a long period Dutch government policy, the RNLN was until 1990 able to fulfil most of its ambitions and capable of participating in operations with the greater Anglo-Saxon navies. In that regard, at first there was nothing new to report for the Dutch admiralty after 1990. Structural out-of-area constabulary missions in peacekeeping, disaster relief and enforcement operations by all the services, in years of ongoing budget cuts, brought in the end bad news for the navy. Even more, because from the year 2000 on, the political focus shifted to land operations. This development made the RNLN change focus with a new doctrine, new choices and new weapon platforms. These choices were both the result of a new security environment as well as of structural diminishing funds.

Nevertheless, after 2014, the tide changed. The international balance of power is unstable and Europe is confronted with a range of threats at the borders of the continent: migration flux and terrorism from Africa and near Asia towards an assertive and aggressive resurgent Russian Federation. Especially the new Russian threat towards Europe and in the North Atlantic, and the assurance of the Dutch government in recent ministerial NATO meetings to spend more money on defence, make the future of the RNLN look less somber.40 In this perspective The Netherlands and Belgium in late 2016 signed an agreement to build together four new Multipurpose frigates (ASW, AAW and BMD tasks) and 12 MCM-vessels, which have to be commissioned from 2023 onwards. In 2017, it became clear that a new large Dutch Combat Support Ship will sail in 2023 and signs are good that on short notice a decision will be made to replace within ten years the ageing Walrus class of four submarines.41 Given these developments, it can hardly surprise that a confident vice admiral Rob Kramer, the current C-ZSK, stated in December 2017 in an intern naval column:

The focus has to shift. After years of small single constabulary missions, like antipiracy or counter drug operations, we have to train again for the task where we are really here for on this world. […] That’s why we will participate in 2018 in three large NATO war exercises in the Atlantic.42

In this perspective for the RNLN the pendulum seems to swing back. Both in the security environment as well as in doctrine/weapon platforms.

1 Leidraad Maritiem Optreden. De Bijdrage van het Commando Zeestrijdkrachten aan de Nederlandse Krijgsmacht (Den Helder: Koninklijke Marine, 2005), 13, 22–23. See also: Maritieme Visie. De Koninklijke marine in 2030. Voor veiligheid op en vanuit zee semi white paper (Den Helder: Koninklijke Marine, 2009), 8–10.

2 Leidraad Maritiem Optreden, 15, 47, 193; Ministry of Defence, Netherlands, Grondslagen van het maritieme optreden Nederlandse maritieme-militaire doctrine (Den Helder: Koninklijke Marine, 2014), 67.

3 Anselm J. van der Peet, Out-of-area. De Koninklijke Marine en multinationale vloot-operaties 1945–2001 (Franeker: Van Wijnen, 2016), 17–18, 189–192.

4 Jaarboek van de Koninklijke Marine 1990 (‘s-Gravenhage/Bergen: Koninklijke Marine/Afdeling Maritieme Historie, 1991), 286–302; D.C.L. Schoonoord, Pugno Pro Patria. De Koninklijke Marine tijdens de Koude Oorlog (Franeker: Van Wijnen, 2012), 318–320.

5 Kees Turnhout, ‘Klopt de som nog wel?’, in Woelige baren. Uitgave ter gelegenheid van 125 jaargangen Marineblad, eds. Onno Borgeld, Marion Lijmbach, Anselm van der Peet (Den Haag: KVMO, 2015), 26–27.

6 H. van Foreest, ‘Uitgeleide’, Marineblad 101, no. 11 (November 1991): 435–436; Van der Peet, Out-of-area, 445–446.

7 Homan, C. and R.T.B. Visser, ‘“Nederland heeft geen ‘area’, de hele vrije zee is ons gebied.” Een interview met eskadercommandant schout-bij-nacht J.D.W. van Renesse,’ Marineblad 95, no. 9 (1985): 384–393; Van der Peet, Out-of-area, 124, 131, 129, 186; Schoonoord, Pugno Pro Patria, 133.

8 Van der Peet, Out-of-area, 125, 163–166, 172–180.

9 Jan Hoffenaar, ‘De krijgsmacht in historisch perspectief’, in Krijgsmacht. Studies over de organisatie en het optreden, ed. E.R. Muller (Alphen aan den Rijn: Kluwer, 2004), 37.

10 Jan Willem L. Brouwer, ‘Dutch naval policy in the Cold War period’, in Strategy and Response in the Twentieth Century Maritime World. Papers presented to the Fourth British-Dutch Maritime History Conference ed. Jaap Bruijn (Amsterdam: Bataafsche Leeuw, 2001), 43–48.

11 Robert Gardiner, ed., Navies in the nuclear age. Warships since 1945 (London: Conway Maritime Press, 1993), 152; Van der Peet, Out-of-area, 94, 157, 328, 476.

12 Ko Colijn and Paul Rusman, Het Nederlandse Wapenexportbeleid 1963–1988 (‘s-Gravenhage: Nijgh & Van Ditmar Universitair, 1989), 519.

13 Van der Peet, Out-of-area, 101–105, 120–121, 437–438, 444–445.

14 Ibid., 370–371, 438–439.

15 Ibid., 347–354.

16 Christ Klep and Richard van Gils, Van Korea tot Kaboel. De Nederlandse militaire deelname aan vredesoperaties sinds 1945 (Amsterdam: Boom, 2005), 445–449; Van der Peet, Out-of-area, 364, 438–439.

17 P. van den Berg, ‘De Koninklijke Marine: koersvast in een onzekere wereld’, Militaire Spectator 182, no. 11 (November 2013): 473–474.

18 Gijs Rommelse, ‘Follow me’ De M-fregatten van de Karel Doorman-klasse (Franeker: Van Wijnen, 2008), 81–83.

19 Ch. van den Berg, Hollandse Nieuwe. Introductie van de Patrouilleschepen Marine Warfare Centre (Den Helder: Koninklijke Marine, 2013), 11–12.

20 Schoonoord, Pugno Pro Patria, 164, 203.

21 M.C.F. van Drunen, Jaarboek van de Koninklijke Marine 1996 (‘s-Gravenhage: Koninklijke Marine/Instituut voor Maritieme Historie, 1997) 170; ‘Belgisch-Nederlandse marinesamenwerking’, Marineschepen.nl, accessed 30 March 2017, https://marineschepen.nl/dossiers/belgisch-nederlandse-samenwerking.html.

22 Grondslagen van het maritieme optreden, 5.

23 ‘Belgisch-Nederlandse marinesamenwerking’, Marineschepen.nl, accessed 30 March 30 2019, https://marineschepen.nl/dossiers/belgisch-nederlandse-samenwerking.html.

24 ‘Nederland vervangt marineschepen samen met België’, Ministerie van Defensie, accessed 30 March 2019, www.defensie.nl/actueel/nieuws/2016/11/30/nederland-vervangt-marineschepen-samen-met-belgie.

25 Handelingen Tweede Kamer (HTK) 2015–2016, 33 763, no. 93, January 25, 2016; Thorsten Jungholt, Wie von der Leyen die europäische Armee vorantreibt, Welt, 4 February 2016.

26 ‘Wat houdt de Duitse en Nederlandse marinesamenwerking nu echt in?’, Marineschepen.nl, accessed 30 March 2019, https://marineschepen.nl/nieuws/Wat-houdt-Nederlands-Duitse-marinesamenwerking-in-050216.html; Lars Hoffmann, ‘German Armed Forces To Integrate Sea Battalion Into Dutch Navy’, Defense News, accessed 30 March 2019, www.defensenews.com/naval/2016/02/05/german-armed-forces-to-integrate-sea-battalion-into-dutch-navy/.

27 Sim Schot, ‘Inzet Zr.Ms. Karel Doorman. Size does matter’, Marineblad 125, no. 7 (2017): 16–18; ‘Karel Doorman klasse JSS’, Marineschepen.nl, accessed 30 March 2019, https://marineschepen.nl/schepen/jss.html; ‘Karel Doorman oefent met Duits Seebatallion’, Marineschepen.nl, accessed 30 March 2019, https://marineschepen.nl/nieuws/Karel-Doorman-oefent-met-Duits-Seebataillon-040918.html; Tobias Buck, ‘German armed forces in “dramatically bad” shape, report finds. Capacity stretched by shortage of equipment and thousands of unfilled posts’, Financial Times, 20 February 2018.

28 Leidraad Maritiem Optreden, 15, 27, 35; Van den Berg, ‘De Koninklijke Marine’, 473–474; M. de Natris, ‘Belgisch-Nederlandse samenwerking: kansen of gedoe?’, Marineblad 127, no. 2 (2017): 11–13; ‘Duits Seebatallion wordt onderdeel van Nederlandse marine’, Duitsland Instituut, accessed 30 March 2019, https://duitsland-instituut.nl/artikel/15022/duits-seebataillon-wordt-onderdeel-van-nederlandse-marine; ‘Waarom Duitsland de Karel Doorman wil gebruiken’, Marineschepen.nl, accessed 30 March 2019, https://marineschepen.nl/Waarom Duitsland de Karel Doorman wil gebruiken.

29 Klaas Visser, ‘Bezuiniging op Defensie, de sociaaleconomische gevolgen – 25 jaar later’, in Woelige baren. Uitgave ter gelegenheid van 125 jaargangen Marineblad, eds. Onno Borgeld, Marion Lijmbach, Anselm van der Peet (Den Haag: KVMO, 2015), 20.

30 R. de Wijk, ‘Defensiebeleid in relatie tot veiligheidsbeleid’, in Krijgsmacht. Studies over de organisatie en het optreden, ed. E.R. Muller e.a. (Alphen aan den Rijn: Kluwer, 2004), 147–177, 67.

31 Ministerie van Defensie, ‘Kerngegevens Defensie. Feiten en cijfers’, accessed 30 March 2019, www.defensie.nl/overdefensie/inhoud/feiten-en-cijfers; Roy de Ruiter, ‘De worsteling van de krijgsmacht na de Koude Oorlog’, in Woelige baren, eds. Onno Borgeld et al. (Den Haag: KVMO, 2015), 18.

32 ‘Marinekazerne Amsterdam dicht in 2018’, Marineschepen.nl, accessed 30 March 2019, https://marineschepen.nl/dossiers/marine-kazerne-amsterdam-dicht.html; ‘Rijk en Amsterdam ontwikkelen samen marineterrein verder’, Ministerie van Defensie, accessed 30 March 2019, www.defensie.nl/actueel/nieuws/2018/07/10/rijk-en-amsterdam-ontwikkelen-samen-marineterrein-verder.

33 Eric Vrijsen, ‘Van Ghent blijft open: goed werk Aboutaleb en Hennis!’, Elsevier Weekblad, 27 February, 2014, 18.

34 E.J. de Bakker en R.J.M. Beeres, ‘Hoeveel investeren is duurzaam?’, Militaire Spectator 182, no. 12 (December 2013): 548–561.

35 In 2013, Minister of Defence J. Hennis-Plasschaert at first decided to sell the unfinished Karel Doorman because of further cuts in the Defence budget. The vessel was saved after rightwing opposition parties demanded minor extra funding of some specific military assets in return for their support on other political issues. Also, it had to sail with a reduced crew. Source: Annemarie Kas e.a., ‘Begrotingsakkoord: overzicht van de maatregelen (en wie wat binnenhaalde)’, NRC Handelsblad, 12 October 2013; www.defensiebond.nl/defensie/karel-doorman-in-vlissingen-gedoopt/; HTK 2014–2015, 33 763, 33 694, no. 81, 19 June 2015.

36 ‘Amsterdam bevoorradingsschip’, Marineschepen.nl, accessed 30 March 2019, https://marineschepen.nl/schepen/amsterdam.html; ‘Antwoorden op schriftelijke vragen over Zr.Ms. Karel Doorman’, Ministerie van Defensie, accessed 30 March 2019, www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=10&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwj6uf6Cs5LeAhVI3aQKHZPPCQcQFjAJegQIAhAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.rijksoverheid.nl%2Fbinaries%2Frijksoverheid%2Fdocumenten%2Fkamerstukken%2F2016%2F05%2F13%2Fbeantwoording-kamervragen-over-zr-ms-karel-doorman%2Fbeantwoording-kamervragen-over-zr-ms-karel-doorman.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1TibJ4edjH4GfbbjXLkmR_. The JSS Karel Doorman was among others built to replace the ageing auxiliary Zuiderkruis (1976), which was sold for scrap in 2012.

37 P.W.C.M. Cobelens, K.A. Gijsbers, ‘Gezamenlijk en gecombineerd optreden van de krijgsmacht’, in Krijgsmacht, ed. E.R. Muller e.a., 663, 671–674; D.J. Kuijper, ‘Grondslagen van het Maritieme Optreden. Een vernieuwende, binationale maritieme doctrine’, Militaire Spectator 182, no. 6 (June 2013): 287, 281–282.

38 Arthur ten Cate e.a., Over grenzen. Het Korps Mariniers na de val van de Muur, 1989–2015 (Amsterdam: Boom, 2015), 58, 60; Jaarboek van de Koninklijke Marine 2003 (‘s-Gravenhage: Koninklijke Marine/Instituut voor Maritieme Historie, 2004), 19, 21; De Ruiter, ‘Worsteling van de krijgsmacht’, 18; ‘Bevelhebbers der en Commandanten Zeestrijdkrachten’, Marineschepen.nl, accessed 30 March 2019, https://marineschepen.nl/dossiers/commandant-zeestrijdkrachten-en-bevelhebber-der-zeestrijdkrachten.html.

39 Ten Cate, Over grenzen, 306–329; www.defensie.nl/onderwerpen/missie-in-somalie/antipiraterij.

40 Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, Frank Notten, ‘De opkomst van nieuwe militaire supermachten, De gedaalde uitgaven aan defensie door Nederland en de NAVO in internationaal perspectief’, De Nederlandse economie, September (2015), no. 04; Centraal Planbureau, Macro Economische Verkenning 2016, September (2015); Emilie van Outeren, ‘Er is meer geld voor Defensie, maar veel gaat dat niet helpen’, NRC Handelsblad, 26 March 2018; ‘Amerikanen “happy” met Nederlandse minister van Defensie Bijleveld’, NOS, accessed 30 March 2019, https://nos.nl/artikel/2201863-amerikanen-happy-met-nederlandse-minister-van-defensie-bijleveld.html.

41 Dutch Minister of Defense, Bijleveld-Schouten, Vaststelling van de begrotingsstaten van het Ministerie van Defensie (X) voor het jaar 2019, HTK 2018–2019, 35000X, no. 2 (18 September 2018), pp. 40–41; Joris Janssen Lok, ‘“Make Navies Great Again”. NAVO-landen investeren in nieuwe oppervlakteschepen’, Atlantisch perspectief 41, no. 1 (2017): 35; ‘Combat support ship/bevoorradingsschip Den Helder’, Marineschepen.nl, accessed 30 March 2019, https://marineschepen.nl/schepen/combat-supportship.html; https://marineschepen.nl/schepen/nieuwe-fregatten-2023.html; “Nieuwe mijnenbestrijdingsvaartuigen (België en Nederland),” Marineschepen.nl, accessed 30 March 2019, https://marineschepen.nl/schepen/nieuwe-mijnenjagers-2025.html; ‘Vervanger Walrusklasse onderzeeboten’, Marineschepen.nl, accessed 30 March 2019, https://marineschepen.nl/schepen/nieuwe-onderzeeboten-2025.html.

42 Vice-admiraal Rob Kramer, ‘Spagaat’, C-ZSK Column, Intranet Ministerie van Defensie, 19 December 2017.