Gilded Neighbors, Progressive City

In 1868, Washington stood outside the social pale. No Bostonian had ever gone there. One announced one’s self as an adventurer and an office-seeker, a person of deplorably bad judgment, and the charges were true.

—Henry Adams, 1918

By the election of 1876, Washington had become an attractive city for new millionaires searching for a suitable place to flaunt their wealth and for those who wished to settle close to the radiance of federal power. For families like the Cabots of Boston, the Biddles of Philadelphia, and the Coopers of New York, the capital would remain beyond the pale. But the new arrivals, who would be counted parvenus if they tried to scale the very highest peaks of American society in the old cities of the Northeast, found Washington to be a place where they might make an indelible mark upon the world as entrepreneurs or members of Congress, and where they might gain influence with those at the center of the nation’s political power. No matter that many had more than one past, and some had made their millions in questionable ways. They brought new energy to the capital and ushered in its Gilded Age.

The civic improvements undertaken by Alexander Robey Shepherd, President Grant’s energetic governor of the District of Columbia, made it possible for entrepreneurs to create new neighborhoods for the capital’s increasing population. Before the Civil War, most of Washington’s prominent citizens had lived in Georgetown, on Capitol Hill and in the southwest, on Seventh Street around Pennsylvania Avenue, and in the few blocks west of the White House. Beyond those areas and even within them, the city was, as one reporter said, a “Slough of Despond”; Shepherd had turned it into “one of the finest cities in the world.” Just in time for the nation’s centennial in 1876, workers tore up the wooden blocks on Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol to the Treasury and replaced them with the latest—and smoothest—road surface, asphalt. As the capital became more attractive, senators, congressmen, and cabinet members decided to bring their families to the city. Boardinghouses and group messes yielded to imposing houses and large apartments.

Many of those arriving looked to the northwest, out Vermont Avenue to Thomas Circle (named after General George Henry Thomas, who saved the Union Army at the Battle of Chickamauga), or out Connecticut Avenue to the as yet unnamed Dupont Circle at the intersection of Massachusetts and New Hampshire avenues. Edward Weston of New York City and Yonkers saw an opportunity to invest in Thomas Circle. Having made his fortune in banking and railroads, the “retired capitalist,” as a story in the Washington Post called him, built a five-story brick townhouse at Fourteenth and K streets NW shortly after his arrival in 1878. Two years later he hired Adolf Cluss to design “Portland Flats,” a six-story apartment house, one of Washington’s first, on the pie-shaped intersection on the south side of Thomas Circle. The Portland’s large, balconied viewing tower facing onto the circle reminded many of the large steam-powered ocean liners now cruising the Atlantic. Its thirty-nine apartments included rich wood carvings, ebony mantels over the fireplaces, and an abundance of marble. Even though the rents were exorbitant—$150 a month for the largest apartments, about $3,000 today—they attracted wealthy members of Congress and government leaders along with other newcomers of means.

William Morris Stewart was among the first to arrive at Dupont Circle. His was a typical nouveau riche story: a native of western New York, he had combined his nimble intelligence with brash self-assurance to make a fortune in the California gold rush. Soon he had acquired enough money to abandon his pick and shovel for a career as a mining lawyer. He quickly became district attorney in Nevada City, and briefly served as attorney general for the state of California. By 1859 he had moved to Virginia City, Nevada, the center of the newly discovered Comstock Lode. Litigation on behalf of large mining corporations brought him even more wealth, and the nickname “the Silver King,” though his enemies—including Mark Twain, who skewered him in two bitter sketches—maintained that he frequently cheated on stocks and bribed judges to get his way.

This early twentieth-century photograph reveals much about the city. At the center and framed between Fourteenth Street and Vermont Avenue is the ship-like High Victorian Gothic Luther Place Memorial Church. (Martin Luther’s statue can be seen in front of the church.) Note the gaslights, the formal gardens surrounding General Thomas’s statue, the baby pram, the street cleaner, and the horse-drawn car line leading to the north. Credit: Library of Congress

Stewart’s rise to power and his championing of mineral exploitation with a minimum of government supervision endeared him to politicians. When Nevada gained statehood in 1864, the governor appointed him to be its first senator. A moderate Republican, he blocked some of the more pitiless and cruel measures of his radical reconstruction colleagues. However, he helped to draft the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which gave black American men the right to vote.

Stewart’s forte always lay in speculation, and Washington offered him abundant opportunities. After the war, he and a group of gold and silver millionaires formed “The Honest Miner’s Camp,” a syndicate that purchased land around Dupont Circle for ten cents per square foot. That much of the vast acreage was swampy, and drained by Slash Run, a creek that generations of misuse had turned into an open sewer, accounted for the price. Most likely the syndicate stretched the meaning of “honest,” as the members were well connected with Alexander Shepherd, and knew he intended to turn the creek into a covered sewer, and to build a new bridge to Georgetown at P Street. They knew, too, that the Metropolitan Railroad Company, of which Shepherd was president, was laying track for a horsecar line up Connecticut Avenue; Shepherd had built his own house at the corner of K Street and Connecticut Avenue. A park at the circle built by the Army Corps of Engineers completed the transformation. And recognizing the importance of the money The Honest Miner’s Camp had brought, the Corps of Engineers named the area “Pacific Circle.”

The cleared land only awaited the builders. William Morris Stewart was the first with an extravagant brick and mansard roof pile at the intersection of Connecticut and Massachusetts avenues that his architect topped with a five-story circular tower in the French Victorian style. Charges that funds for the house came from a mining swindle—“The House you have built and furnished is with my money, and you know it,” wrote one man, who charged that Stewart had cheated him of half a million dollars—meant little to the senator, or to the many visitors who rode out Connecticut Avenue to see the extravagant structure. The senator thought that Stewart’s castle, as it was called, was just the house for his Mississippi-born wife and three daughters.

In the 1880s and 1890s, others equaled Stewart’s excess with opulent mansions of their own: James G. Blaine, Republican congressman and senator from Maine whose wealth was tainted with railroad and land scandals, placed his mansion just off the circle at Twentieth and Massachusetts in 1882. George Hearst, another Comstock Lode millionaire, enlarged an already considerable mansion on New Hampshire Avenue for his family. (Although the nearly illiterate Hearst had a reputation for crudeness of language and behavior, his wife, Phoebe, became a civic leader. She helped to establish the Parent Teachers Association and kindergartens across the city, and gave away more than $20 million to cultural institutions and charities.) Levi Leiter, a real-estate and dry-goods tycoon from Chicago, built a three-story white-brick mansion with fifty-five rooms for his wife and three marriageable daughters on New Hampshire Avenue north of the circle. (Two daughters would wed British nobility; the third, a British major.) By the turn of the century, more than a hundred fashionable houses lined the avenues and surrounded the circle, which in 1884 was renamed in honor of the Civil War admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont.

Over the years, George Washington’s vision of a capital that was a gateway to the West and a center of manufacturing gradually receded in the minds of Washingtonians. Most traces of the Washington Canal had vanished entirely. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal that terminated at Georgetown had never become the major commercial artery that its creators dreamt of when they began it in 1828. Floods frequently disrupted shipping, and a devastating deluge in 1889 forced the company to declare bankruptcy. (The company would limp along into the first quarter of the twentieth century, until another flood in 1924 forced it to cease altogether.) Nor had the city become a national manufacturing center, as the schemes of early residents like John Peter Van Ness had once promised.

But there were successful local businesses that grew up to supply the needs of the transient population of elected officials, diplomats from foreign nations, and permanent residents, including government workers, immigrants, and blacks. Over two decades between 1870 and 1890, Washington’s population grew from 109,000 to 230,000. A number of them had come to Washington because they saw an opportunity to prosper.

Samuel Walter Woodward and Alvin Mason Lothrop arrived from New England in 1880 to open the Boston Dry Goods Store at Seventh Street and Pennsylvania Avenue; by the turn of the century the Woodward and Lothrop Department Store commanded an entire block on Tenth and Eleventh between F and G streets, with over a thousand employees and a fleet of delivery wagons. Fashioning their enterprise on the merchant prince John Wanamaker’s Philadelphia emporium, Woodward and Lothrop stocked a little bit of everything, imported Paris fashions (after the World’s Fair of 1893) to the capital, and made shopping a pleasure for their customers, especially for ladies, who could rest in the store’s reception room on the mezzanine. The store was among the first to anticipate the seasons; customers in July could peer through “highly polished French plate glass” windows at the latest winter coats, and in January at summer frocks. The merchants allowed returns and exchanges of merchandise and established a “one price” policy that freed customers from the task of bargaining over every purchase.

Woodward, who was also the president of the enterprise, appeared to be the model of rectitude—slightly priggish in his tightly buttoned coat, wing-tip collar, and tie, his pince-nez, and his carefully trimmed handlebar mustache, goatee, and sideburns. He headed the Board of Trade, served as president of the YMCA and vice president of the National Metropolitan Bank, and prayed regularly at the Calvary Baptist Church. Men of Mark in America, a puff volume of the time dedicated to “biographies of eminent living Americans” that illustrated the “ideals of American life,” said that Woodward’s employees felt “the bracing effect of [his] strict but kind oversight.” In their memories, however, employees had a somewhat different definition of bracing and kind. They told of a man quick to anger who regularly threw pens across the office whenever the nib gave out; who mercilessly cross-examined buyers when they returned from trips; who ordered the windows curtained on Sundays; and who, presumably because they promoted loose morals, forbade the sale of playing cards.

Soon, Woodies, as it was known throughout the city, had imitators. Kann’s opened in 1893, Hecht’s three years later, and Garfinckel’s in 1905. To meet their new competition, older dry-goods stores, including Lansburgh’s—which had supplied the mourning crepe for Lincoln’s funeral—and the Palais Royal expanded their offerings.

Christian Heurich arrived from Germany by way of Baltimore in 1872 and purchased one of Washington’s five small breweries at Twentieth Street and M; by the turn of the century, the Christian Heurich Brewing Company was operating from a new four-story, fireproof building on the Potomac in Foggy Bottom (at the site of today’s Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts). It had the capacity to produce half a million barrels of beer annually. Across the city, even in the White House, Washingtonians were drinking Heurich’s Senate Lager, so much lager that Christian Heurich could count himself a millionaire.

Heurich capitalized on the fact that Gilded Age Washington needed a large group of working- and middle-class artisans and merchants to support its ostentation, and that these workers, too, thirsted for entertainment. While the “cave dwellers” (as the earliest inhabitants were known), diplomats, and members of Congress took their whiskey and wine in townhouse parlors on Connecticut Avenue and the halls of the Capitol, government clerks, store owners, and immigrants working on Alexander Shepherd’s municipal projects drank their beer in saloons and beer gardens. Even before the creation of the District of Columbia, small enclaves of Germans had lived in the area, especially in Jacob Funk’s Hamburg; but emigration from Germany rose significantly in the second half of the nineteenth century. There were about 5,000 German Americans in Washington when Heurich arrived. They read two German-language newspapers. They had a gymnastics club and two shooting clubs, and at the Capital Saengerbund they sang traditional German songs. These were the consumers Heurich sought to please; neighborhood saloons across the city, including one attached to the brewery, became social centers, the places where a man might go after a day’s labor for the company of friends and, in Heurich’s terms, “good German lager.”

The city’s burghers were just as quick to weave the successful German immigrant into their elite social fabric as they were millionaires from the West. Heurich’s decision to invest much of the profit from his brewery in Washington real estate and rental buildings made him even more welcome. He became a member of the Chamber of Commerce and a charter member of the Washington Board of Trade; and he joined the boards of such German American philanthropies as the Eleanor Ruppert Home for Aged Indigent Residents and the German Orphan Asylum. Like many men of means, he kept a farm nearby in Maryland. On New Hampshire Avenue and Twentieth Street, he erected a grand and modern fireproof mansion in the Romanesque Richardson style. Elaborate cabinetry and iron work executed by immigrant German craftsmen, furniture handcrafted in Germany, and a bierstube in the basement complete with carved drinking mottoes reminded Heurich whence he came and signaled to others all he had achieved.

In 1868, Amzi Lorenzo Barber moved from Ohio to Washington, DC, to do good. The son of a Congregationalist minister, Barber’s upbringing and education at Oberlin College was egalitarian and abolitionist. Upon his arrival, he took a position in the Normal Department at Howard University and a seat on the board of trustees. Just a year later, he married, resigned his university position, and joined his brother-in-law Andrew Langdon to take advantage of the capital’s growing need for real estate. From that moment on, Amzi Lorenzo Barber did well.

For their first speculation Barber and Langdon purchased land from the university to build a suburban residential community beyond the boundary of Washington City. The fifty-five-acre triangular plot was wedged between present-day Florida and Rhode Island avenues on the south, and the university property and group of modest dwellings called “Howard Town” on the north. To honor the first name of their father and father-in-law, the partners named their new community LeDroit Park.

By design, LeDroit Park had the romantic air of an exclusive rural setting within the city. The plantings would be lush, the streets (though off the axis of L’Enfant’s plan) would be quiet, and no fences or walls would separate the properties. Barber and Langdon hired the enterprising architect and contractor James H. McGill to design and build the houses and oversee the grading of streets, the installation of gas, water, and sewer lines, and the laying of brick sidewalks. McGill freely adapted plans and ideas he found in Cottage Residences and Villas and Cottages, books by two of America’s most influential architects of the time, Andrew Jackson Downing and Calvert Vaux. He especially favored those in the Gothic and Italianate style. The contractor built and appointed the houses and publicized them in a book with the capacious title James H. McGill’s Architectural Advertiser: A Collection of Designs for Suburban Houses, Interspersed with Advertisements of Dealers in Building Supplies. By 1876, LeDroit Park counted, one newspaper reported, “forty-one superior residences . . . no two being alike either in size, shape or style of finish, or in the color of exterior.” McGill and his family lived in one of his houses, 1945 Harewood Avenue (present-day Third Street).

LeDroit Park would attract middle-class Washingtonians—white doctors, teachers, lawyers, and other professional men who relished their isolation, yet needed to have easy access by the horsecar line on Seventh Street to downtown two miles away. Congressman and later commissioner of patents Benjamin Butterworth chose LeDroit, as did the geographer who is often called the “father of government mapmaking,” Henry Gannett, and the former Civil War general and lawyer William Birney. The developers intended LeDroit Park to be segregated and gated. To make certain that blacks other than servants would not walk down the streets of their community, Barber and Langdon erected a wooden and cast-iron fence around the site, placed gates at the southern entrance, and hired a guard to keep watch at night. No one could enter from the north.

But the fence did not last. By 1887, groups of angry residents of Howard Town—who had to walk around the property to get to their jobs downtown—began to tear it down. A legal opéra bouffe ensued, with the antagonists alternately tearing down and boarding up the street entrances; installing and snipping though barbed wire; and filing suits and countersuits. In March 1891, the Washington Post reported that the fence “suddenly disappeared,” and no one seemed to know who had spirited it away. In August a judge ended the comedy with a ruling that the fence must be permanently removed.

Racial barriers in LeDroit Park also began to crumble, though not without hostility. When Octavius Augustus Williams, a barber who cut hair at the Capitol, moved into 338 U Street, someone fired a bullet through the window as his family was eating dinner. Robert and Mary Church Terrell had to resort to subterfuge to purchase a home there. Though Robert had graduated from Groton School and Harvard and held a law degree from Howard University, and Mary had a degree in classics from Oberlin and taught Latin at the city’s new “Preparatory High School for Colored Youth” on M Street, the owner of the house at 326 T Street refused to sell it to them. To work around that resistance a white businessman purchased the property and immediately resold it to the Terrells. Middle-class black families like the Williamses and the Terrells gradually and steadily moved into the neighborhood. The result, however, was not an integrated community. The white middle-class families moved to other suburbs made ever more accessible by streetcar lines.

In October 1897, the black poet and novelist Paul Laurence Dunbar and his wife moved into a LeDroit Park house. Dunbar’s lyrics often contained lines about the plight of blacks:

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,—

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

Such poems earned Dunbar national and even international popularity, but he still had to take menial jobs in Ohio to support himself and his mother. When a sympathetic Ohio congressman heard of Dunbar’s position, he arranged for him to become an assistant in the reading room at the Library of Congress for $750 a year. But long hours in the library and the dust from the books diminished Dunbar’s already frail health; after being diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1898, the poet went to Colorado. Although his residence in the capital was brief, Washingtonians were eager to recognize him. In 1916, the city’s school board named its new segregated high school after Dunbar, “whose name is a household word,” an editorial in the Washington Bee said, “in the home of every American negro.”

By 1881, Amzi Lorenzo Barber had moved on to his next great venture, another housing project, with John Sherman, the secretary of the treasury. Sherman acquired a large tract of land north of Boundary Street (today’s Florida Avenue) between Tenth and Sixteenth, and Barber set out to market it as the newest and best suburban development. As much of the land had belonged to the small and struggling Columbian College, he named it “Columbia Heights.” “Under the rapid growth of Washington,” read the advertisement in the 1882 edition of Boyd’s City Directory, “this property will soon become the most desirable and fashionable part of the City.” Columbia Heights would appeal to the “Creme de la Creme.”

Barber saved ten acres of the choicest land for himself. There he built “Belmont,” a granite mansion executed in the Romanesque and chateau styles and graced at its corner with a slender, round, four-story Queen Anne tower topped by a narrow conical roof. From the dormer windows of Belmont’s tower, which dwarfed William Morris Stewart’s castle at Dupont Circle, Barber could take in downtown Washington and the Potomac. And he could see the city’s streets—seventy miles of them by 1890—that he had paved with the best material available, Trinidad asphalt.

In part, the new pavements were a response to a craze that began to overtake the nation in 1878, when Union Army veteran Albert Augustus Pope of Boston introduced the Columbia bicycle. To promote his bicycles and smooth roads, the former colonel formed the League of American Wheelmen in 1880, which lobbied for highway improvements. At the time, there were about 175 wheelmen in the District, who rode their “iron horses” over forty-five miles of paved roads. By 1895 there were at least five bicycle stores doing a brisk business in the capital, with about 12,000 bicyclists in the city. A number of the cyclists formed the Capital Bicycle Club, which held annual races around Iowa (now Logan) Circle with rival bicycle clubs from Baltimore and Arlington as well as distance races in Maryland and Virginia.

Recognizing the American desire for mobility, speed, and good roads, as well as the success of the recently paved Pennsylvania Avenue, Barber decided in 1878 that his future wealth lay in asphalt paving. In the coming years he would demonstrate his prescience, business acumen, and ruthlessness to control the entire industry. He gained a near monopoly on the source of bitumen, or pitch, the key ingredient of asphalt, improved paving machinery, rapaciously bought out smaller competitors, and tied up other challengers with lawsuits that stopped or at least impeded their progress. Believing that the automobile would supplant the bicycle and increase the demand for paved roads, he also helped found the Locomobile car company in 1899. By the end of the century he could boast that the Barber Asphalt Company had paved the streets in one hundred cities and half the paved roads in America. Amzi Lorenzo Barber was “The Asphalt King.”

But early in the new century, the kingdom collapsed. Barber failed in his attempt to buy up all the competing asphalt companies. He died in greatly reduced circumstances in 1904. Belmont remained in the family until 1915, when a syndicate of Washington real-estate investors purchased the property and razed the mansion for a new residential development, the Clifton apartment houses.

Henry Adams believed to his core that his family had been put upon the earth to serve the public good. The Adamses held a hereditary claim upon Washington, the nation’s government, even the White House. His great grandfather, John Adams, had served in the Continental Congress; had helped to draft the Declaration of Independence, and later to negotiate the Treaty of Paris; and was the first president to live in the executive mansion. His grandfather, John Quincy Adams, had learned diplomacy as secretary to his father in Europe and had served as secretary of state under James Madison; he had become the sixth president, and after his defeat for reelection in 1828, had served nine terms in the House of Representatives. His father, Charles Francis Adams, had served as the US ambassador to Great Britain during the Civil War, had twice run unsuccessfully for vice president, and had wished to follow his father to the White House.

Clearly, by the fall of 1868, Henry thought the mantle of his family’s public service had come to rest upon his shoulders. Just as John Quincy had served as diplomatic secretary to his father, so Henry had attended his father in London during the Civil War. However, his would be a different kind of public service. To Charles Francis Adams’s distress, his thirty-year-old Harvard-educated son would be a reformer: he would “join the press,” as Henry put it, and in Washington, not Boston. The decision was in part a mild rebellion against his New England roots, but Henry had felt a strange affinity for the capital from the time of his first visit to his grandparents’ house on F Street in 1850. Although Bostonians might consider Washington “outside the social pale,” Henry Adams found it to be “the drollest place in Christian lands.” He took a house on G Street—suitably removed from Lafayette Square—with views of the Potomac and Georgetown. The government buildings remained “unfinished Greek temples,” the roads were “sloughs,” and “a thin veil of varnish” covered “some very rough material”; but, as he wrote to an English friend, from the window of his house he could “see for miles down the Potomac,” and he knew “of no other capital in the world which stands on so wide and splendid a river.”

It was a bold step, a “leap into the unknown,” Adams later acknowledged in his famous Autobiography, but he scarcely realized how hard his landing would be. He would not be a “regular reporter” for a daily paper, but one who would present longer and more considered articles that placed current events in a historical context. For Adams, reform meant steering the government away from the false appeals of the Jacksonian common man and returning it to the noble ideals of the founders. “We want a national set of young men like ourselves,” he wrote his brother—men who would “exert an influence” upon America’s politics, literature, law, and “the whole social organism.” But his arrival in Washington coincided with Grant’s election to the presidency. After the confusion of Andrew Johnson’s stormy tenure, Adams, along with most Americans, looked forward to the general reestablishing “moral and mechanical order” in the land, as he put it in his autobiography; instead, moral and mechanical chaos prevailed. Grant filled his cabinet with knaves and frauds beholden to the interests of a small group of business oligarchs. Henry protested Congress’s imposition of high tariffs (“Capital accumulates rapidly, but . . . in fewer hands, and the range of separation between the wealthy and the poor becomes continuously wider”), Jay Gould and Jim Fisk’s brazen attempt to corner the gold market in 1869, and countless venal acts of Washington officials. Rail though he might, however, his articles counted for little. He was a relic of the eighteenth century, he said, but America, “more eighteenth century than himself,” had “reverted to the stone age.”

The old world of public men, as Henry Adams called them, often Harvard-educated and patrician men like Charles Sumner and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln’s private secretary, seemed to Adams to be in eclipse. In their place came men from recently minted states of the West, with pockets filled with bullion. “Slowly a certain society had built itself up about the government,” he remembered later. “Houses had been opened, and there was much dining; much calling; much leaving of cards; but a solitary man counted for less than in 1868.”

To escape his melancholy, which had been brought on by Grant’s ineptness and his own family’s declining influence at the center of the republic, Adams became a solitary traveler worthy of William Wordsworth. His Lake District was “the dogwood and the judas tree, the azalea and the laurel” of the unspoiled Maryland countryside. The “Potomac and its tributaries squandered beauty,” he wrote, and “Rock Creek was as wild as the Rocky Mountains.” But he could not escape the realities of “vulgar corruption” that he saw about him. “The progress of evolution from President Washington to President Grant,” Adams wrote in discouragement, “was alone evidence enough to upset Darwin.” He had hoped to write of “a new Washington,” but now he saw only a capital that bred “endless corruption.” After two years of witnessing political decay and the devolution of American culture, he left the capital to tour Europe and take a professorship of history at Harvard.

Yet Adams’s heart lay not on the Charles but rather on the banks of the Potomac; so in 1877 he decided to retire from Harvard and return. To be sure, signs of the firm grip exerted by amoral mediocrities upon all branches of the government were everywhere: in the Supreme Court, peopled by justices who resolutely affirmed the power of business; in the Congress, controlled by mendacious frauds; and in the executive branch, headed by one mediocre president after another. Although his political future as a reforming journalist may have been thwarted in 1869, Adams realized that his strong suit lay in writing. He would mine the documents in the State Department and the Library of Congress for a chronicle of the Jefferson and Madison administrations, a time before America’s moral ideals had been sullied by political corruption.

Adams returned to Washington with a wife, Marian “Clover” Hooper, the same young Boston woman who had been in Washington in May 1865, at the grand military parade marking the end of the Civil War. Her father, a wealthy Boston doctor, and her mother, the Transcendentalist poet Ellen Sturgis Hooper, had ensured that their daughter received the best education of the time, at a school for women run by the family of Louis Agassiz, where the great Harvard professor occasionally lectured on “physical geography, natural history, and botany.” Henry considered his wife to be “not handsome; nor would she be called quite plain,” as he wrote to an intimate English friend; but, he said, “She knows her own mind uncommonly well. . . . She talks garrulously, but on the whole pretty sensibly.” She was tractable, too, he believed, “open to instruction.” And, he added in his best masculine temper, “We shall improve her.” It didn’t hurt, either, that Clover had “enough money to be quite independent.” His income and hers, and often a generous check from Dr. Hooper, enabled the couple to live as they wished.

Henry and Clover’s wish was to make their refined mark on society. They rented a mansion from William Corcoran at 1607 H Street at the north end of Lafayette Square for $2,400 a year, and in late 1880, after extensive refurbishing, moved into it with fifteen wagonloads of furniture and objets d’art gleaned from their travels around the globe, and a staff of six servants. From the front windows, they could look past the statue of the Adams family nemesis, Andrew Jackson, to the White House. Although Henry had called the present occupant of the White House, Hayes, a “third rate nonentity,” and other detractors called Hayes’s prohibitionist wife “Lemonade Lucy,” the president and Lucy Hayes proved to be most cordial neighbors. Lucy sent Clover “a quantity of cut flowers” to welcome the Adamses to H Street, and more than once she invited the Adamses to dine with them. Henry was careful to confine most of his political thoughts to patronizing comments he wrote in letters to American and English friends.

The couple prized the richness of elegant, intellectual social intercourse. Soon Henry and Clover opened their doors for teas, discreet dinner parties, and worldly gossip. Theirs was a select circle of guests whom they found intelligent and amusing. More than a house with a pleasant reception room, 1607 H Street became a salon of quiet refinement in the midst of the noisome political world, a place where intelligent conversation prevailed over crude talk of power. In a private but very public way, the Adamses served as arbiters of all that society should value. “Money plays no part whatever in Society,” Henry wrote to his English friend, “but cleverness counts for a good deal, and social capacity for more.”

Many scientists and diplomats were welcome, but most senators and congressmen, along with Mark Twain, all infra dig, were not. The writer Henry James, who had known both Clover and Henry before their marriage, was welcome, always. James, who had a warm relationship with Clover, likely drew upon her when he limned his portraits of Daisy Miller and Isabel Archer, and he always enjoyed the “perennial afternoon teas” that she hosted. Yet when the novelist asked if he might bring along an Anglo-Irish writer of his acquaintance who was in Washington as part of his lecture tour in America, Clover flatly refused. Oscar Wilde, whose reputation had preceded him, was not welcome at 1607 H Street.

It was not the ever-present political intrigue that kept the Adamses in Washington so much as the city itself. “One of these days this will be a very great city if nothing happens to it,” Henry had once written to a friend. For him, it was steadily approaching the ideal. With every season, Washington took on more of the character of a national capital. As Civil War heroes died, Congress commissioned statues; by 1880, four new ones (commemorating McPherson, Thomas, Scott, and Ulysses Grant’s aide and confidant, John Rawlins) were already in place. In front of the Capitol stood the great white marble Peace Monument dedicated to sailors who had lost their lives in the Civil War. The federal presence was conspicuous across the city: in the Surgeon General’s office, which had taken over Ford’s Theater, where Booth had assassinated Lincoln; in the twenty-six-inch refractor telescope, then the largest in the United States, that had been built at the Naval Observatory on the bank of the Potomac, near today’s Lincoln Memorial; and on the roof of the Army Signal Corps headquarters at 1719 G Street NW, where the War Department had installed a weather station.

This was the Washington that lured Henry Adams and his wife. He and Clover spent their time researching the Jefferson and Madison papers in the State Department for his life of Albert Gallatin, Thomas Jefferson’s secretary of the treasury and minister to France and the United Kingdom, and his multivolume history of the Jefferson and Madison administrations. “As I am intimate with many of the people in power and out of power,” he told his English friend, “I am readily allowed or aided to do all the historical work I please.” He and Clover indulged their passion for horseback riding almost daily in the Virginia countryside, in the Rock Creek Valley, or on the grounds of Harewood and the Soldiers’ Home. By 1882, Henry could report that he was writing for five hours a day, riding for two, and saving his remaining waking hours for “Society.”

For Henry and Clover, “Society” was synonymous with culture and intelligence. The Adamses’ guests reflected the intellectual and scientific ferment that was abroad throughout the capital. America’s expansion across the West, the Smithsonian under the leadership of Joseph Henry, and the Civil War had attracted numerous scientists to the capital. In 1871, Henry organized the Philosophical Society of Washington, where they might discuss “all subjects of interest to intelligent men.” Seven years later, in the year that Joseph Henry died, a number of distinguished men in science created the Cosmos Club, “to bind the scientific men of Washington by a social tie,” but the club also included men of literature and the arts like Henry Adams, who served on its Committee on Admissions. Like the Philosophical Society, the Cosmos Club offered scientists an opportunity to present papers. Major John Wesley Powell served as its first president. He was well known for having lost his right arm at the Battle of Shiloh in the Civil War, but his scientific eminence came from his work as a geologist, anthropologist, and explorer. It was Powell who, in 1869, led an expedition of ten men down the Colorado River and through the Grand Canyon. Those who spoke at the Cosmos Club ranked with the finest scientific minds in the nation, and many were guests at H Street. John Wesley Powell came often, as did Simon Newcomb, the mathematician and astronomer at the Naval Observatory who produced mathematical tables and formulae to show the movement of the planets and stars, and Francis Amasa Walker, the preeminent statistician who in 1880 supervised the tenth Census of the United States.

The scientist who visited most often was the director of the United States Geological Survey, Clarence King. A short, puckish man with a Vandyke beard and bright blue eyes, King regarded geology as scientific history, a perspective that fit well with the view of Henry Adams, who considered himself to be a scientific historian. Their friendship had begun by chance in 1871 in Wyoming, where Adams had been a visiting a member of the Geological Survey, and it intensified after Henry and Clover moved to the capital.

King joined John Hay and his wife, Clara, at 1607 H Street so often that the five became intense companions. By 1882 they were calling themselves the “Five of Hearts.” They had stationery embossed with a playing card and five red hearts, and King gave Clover a tea service with a pot and bowls in the shape of hearts. The friendships were warm and intensely homosocial. King was a confirmed bachelor who had sworn off marriage (though it was later revealed that when in New York City he lived under an assumed name with a black common-law wife). Adams and Hay frequently began their letters with salutations like: “My Beloved,” “Apple of Mine Eye,” or “Light of Mine optics.” Clara and Clover often appeared removed from the center of discussion about scientific and literary subjects, and yet always at the ready to serve in a social role.

Clover’s letters to her father paint a picture of a frenetic life of social, intellectual, and political amusements. Typical is one she wrote on March 27, 1881, in which the names of guests at three evening dinners flows from her pen: Clarence King; Francis Amasa Walker; the retired Civil War general and now Rhode Island senator Ambrose Burnside; secretary of the Swedish legation de Bildt; Attorney General Wayne MacVeagh; Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln (twice); and John Hay (twice). On another evening, Clover reports that Henry went to dine with the historian George Bancroft and his wife; she begged off on account of a cold, but Walker and MacVeagh stopped by “to cheer my solitude.” Their dear friends (“intimates”) Hay and King had left Washington, Hay to join his wife at Fort Monroe, King to search for gold in Mexico. Gossip overflows: about scheming to have John Wesley Powell succeed King as head of the Geological Survey; about President James Garfield’s fractious new cabinet; and about the new assistant secretary of state—“rich, but socially of little use.” She had begun reading Gibbon (“a bone that will take months to gnaw”), and Henry was hard at work on his history of the republic. That week, the Adamses had to decline four dinner invitations—“even Lent does not stop society in this social town,” Clover remarked.

Despite the heady scientific and literary discussions that took place at Sixteenth and H streets, Henry Adams knew he wielded little political power. The intellectual and cultured presence at the Adams house on the north end of Lafayette Square was hardly a counterweight to the crude political intrigues hatched in the White House at the south end. A decade earlier, he had failed to effect any practical reform of the government and had vowed to leave the political world. But the political world could never quite leave Henry Adams. If he couldn’t exert a practical influence upon the political course of the nation, at least he could show his scorn for the ethical decline of the democracy in a satirical novel; and better still, he could do it anonymously, keeping everyone in the capital guessing as to who the author might be. He would publish it on April Fool’s Day, 1880. Even its title would reflect his disgust at the devolution of the noble ideals that had so motivated his forebears in the beginning of the republic: Democracy.

The plot would be simple: an innocent young lady is attracted to and courted by a man of corrupt moral character, only to be rescued from committing herself to marriage by one who reveals awful truths about him. The innocent was Madeline Lightfoot Lee, a naïve but curious New York widow, with $20,000 a year, who decides to pass the winter in Washington with her sister. They would observe life in the capital, the place where “the interests of forty millions of people” were guided “by men of ordinary mould,” men who wielded the great forces of power. She would read reports of Congress and sit in the galleries listening to the great political orators, and she would entertain them at the house she leased at the epicenter of power, Lafayette Square. Madeline Lee would be witness to a great play, Adams suggests, reaching for a metaphor; she would see “how . . . [it] was acted and the stage effects were produced; how the great tragedians mouthed, and the stage-manager swore.”

The man of corrupt moral character, Senator Silas P. Ratcliffe from Illinois, takes the stage in Chapter 2. Called by newspaper writers “the Prairie Giant of Peonia,” Ratcliffe possesses a six-foot frame, a large head, a silver tongue, and an unslakable thirst for power and the presidency. He is the new political man, the one who places his own interests above the ideals of the founders. Ratcliffe is drawn to Madeline, who possesses the refinement and culture he lacks, and who will serve him well when he attains the White House.

To the refined conversation of assorted diplomats, former Confederates, and minor nobility who frequent Madeline’s house, Ratcliffe brings the corruption of the capital. Living up to the nomen est omen of his surname, Ratcliffe speaks of power and political plots, scheming to embarrass, even unseat, the president. On an excursion to Mount Vernon with Ratcliffe, Madeline listens as the senator contends that George Washington’s virtues could not cope with the political realities of the present-day republic: “If virtue won’t answer our purpose, we must use vice.” Madeline believes “the associations with Mount Vernon, indeed, everything Washington touched [were] purified.” Ratcliffe was soiling all that was sacred to democracy.

“Is a respectable government impossible in a democracy?” Madeline asks early in her stay in the capital. Though drawn to Ratcliffe, the great lodestone of power in Washington’s affairs, she comes to realize that men like the senator who dominate Washington no longer act for the public good. Recognizing that she is “not fitted for politics,” she refuses marriage. Her education complete, Madeline Lee returns to New York.

The models for the characters in Democracy were all around in Washington. James G. Blaine, the congressman, senator, and Republican contender for the presidential nomination in 1876, who had been implicated in a colossal railroad bribery scheme, bore a striking resemblance to Ratcliffe. Clover and Henry’s sensibilities and circumstances mirror those of Madeline. Madeline’s natural grace and virtue enable her to resist the vulgar in all its guises. Henry had once shared Madeline’s belief that the politicians in Washington acted with a common understanding of right and wrong and conducted their affairs in an ethical and honest way. And like Madeline, his disillusionment had driven him from the capital to seek diversions in foreign lands. But Henry Adams’s sensibilities resided in other minor characters, too: in the rectitude of a former Confederate who uncovers Ratcliffe’s sale of his vote for $100,000; in the desire of a young New England congressman “to purify the public tone”; and in the speech of a foreign minister who declaims, at one of Madeline’s parties, “I have found no society which has had elements of corruption like the United States.”

Viewing the world through the lens of literature, as he increasingly did, gave Adams the luxury of withdrawing from Washington’s political life. In July 1881, when a crazed Charles Guiteau shot James Garfield as the president was boarding a train at the Baltimore and Potomac Station for a seaside vacation in New Jersey, Adams wrote a friend that Thackeray or Balzac could not have invented so “lurid” a tale as “Garfield, Guiteau, and Blaine.” Several months later he and Clover attended Guiteau’s trial for a day; they even visited the assassin in the city’s jail and asylum at Nineteenth Street and Independence Avenue SE. Clover regarded him as “the accursed beast,” while Henry used the occasion as an opportunity to express his disgust with politicians who played to public sentiment and wanted only for Guiteau to hang. “To say that any sane man would do this,” he wrote, “is a piece of, not insanity, but of idiocy, in the District Attorney.” But public sentiment prevailed, as Adams knew it would. Guiteau went to the scaffold singing, “I am going to the Lordy, I am so glad.”

Satirize the newly minted money and manners of Washington’s Gilded Age though they might, all was not well within the circle of the Five of Hearts, most especially in Clover and Henry’s marriage. Henry proved to be cut from the cloth of an upper-class, late nineteenth-century American male, at times distant, at times critical, and always controlling. His marriage to Clover was barren. By the fall of 1885, Clover Adams was slipping into a deep depression from which she would never recover. On the first Sunday in December, Marian Hooper Adams took her life. The shock of her violent passing left Henry silent. He had her buried in an unmarked grave at Rock Creek Cemetery, near the valley where he and Clover had often ridden. He destroyed Clover’s correspondence and her journals, and never again allowed her name to pass his lips. “I can endure,” Henry wrote to a friend two days after his wife’s death. “But I cannot talk, unless I must.”

Travel—to Japan, to Samoa, and to Europe, among other places—offered Adams little respite from his pain. On his return to Washington in February 1892, Henry went directly to the grave at Rock Creek Cemetery to view the memorial he had commissioned from the Beaux-Arts sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. There Adams beheld a seated figure, cloaked in coarse drapery, whose face, eyes shut, seems to peer into the mysteries of life and death, contemplating forever a world beyond human comprehension.

Adams returned to his wife’s grave again and again. He considered the work in “every change of light and shade . . . to see what the figure had to tell him that was new,” he wrote in his Autobiography. “But,” he added, “in all that it had to say, he never once thought of questioning what it meant.” Not so for others, who speculated about its meaning and gave it titles such as “Sadness” or “Grief.” He knew better. “The interest of the figure was not in its meaning,” he wrote, “but in the response of the observer.” In his unutterable suffering, Henry Adams had given his favorite city a work of haunting and sublime grace.

Although he did not swim in the same refined and intellectual waters of his neighbor Henry Adams, Charles Carroll Glover, who lived in a three-story house at 20 Jackson Place on Lafayette Square, also enjoyed rambles in the wilderness of the Rock Creek Valley. Like Henry and Clover, he frequently followed the paths beside the creek north to Oak Hill Cemetery and the rugged terrain beyond. He, too, saw the broad fields of wildflowers blooming through spring, summer, and into fall, the small and silent dells surrounded by gray barked beeches and oaks, and the tangles of wild honeysuckle. There were small streams to ford; red and gray foxes, flying squirrels, whitetail deer, coyotes, turtles, and northern water snakes were plentiful. On Thanksgiving Day 1888, Glover led a party of two lawyers and the assistant engineer for the District of Columbia on just such a horseback ride. The men knew that developers were fast pushing north from the Potomac to create suburban communities. Much of the landscape they were viewing might soon be prime real estate. To preserve the land, they would have to convince the federal government to make it a national park.

The Adams Memorial as it appeared c. 1935. Adams had Augustus Saint-Gaudens design the statue. Saint-Gaudens turned to his friend Stanford White to design the granite plinth and stele beneath and behind the bronze sculpture as well as the hexagonal plaza and benches. Credit: Library of Congress

Glover had all the proper connections to get his way: his roots were in old Washington, and he counted his ancestors among the District’s original landholders; he was president of the Riggs Bank on Fifteenth Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, across from the Treasury, which held the money of presidents, senators, congressmen, generals, admirals, and foreign legations; and he moved with ease between the offices of the Capitol and the White House. His companions that Thanksgiving were also well connected: two, Calderon Carlisle and James M. Johnston, were lawyers from old Washington families; the third, Thomas W. Symons, an assistant engineer in charge of the city’s water and sewage, had graduated first in his class at West Point, had been a member of the US Geological Survey in the West, and had the respect of the District commissioners. In a meeting at Jackson Place after Thanksgiving, Crosby S. Noyes, editor of the Washington Evening Star and consummate city promoter, pledged his paper’s full support. In mid-January 1889, the men decided upon a plan: Congress was to vote on the creation of a National Zoological Park. To this bill a sympathetic member of Congress introduced an amendment drafted by Carlisle and Johnston, authorizing the purchase of 2,000 acres of land for Rock Creek Park. District residents would pay half the cost of $1.5 million.

The very idea of the United States paying any of the costs of a park for the city raised all the old animosities that congressmen had long harbored about the District of Columbia. Representative Judson Claudius Clements of Georgia declared that the capital’s open squares meant that Washingtonians had more park land than residents of other cities; a representative of Texas voiced the sentiments of many of his colleagues when he said that, if the city’s residents wanted a park, they should pay for it themselves. Another Georgia congressman, James Henderson Blount, argued that the Soldiers’ Home had ample lands for a park. Such bluster swayed the debate; the amendment to the bill lost by ten votes.

But Glover was not discouraged. Congress’s approval of the bill to purchase land in Rock Creek for the National Zoo, over the strenuous opposition of a cadre of southern Democratic representatives who opposed most public expenditures for the District, augured well. The vote for the zoo was timely, too, for thousands were coming daily to see exotic animals from across the continent and the world that the Smithsonian was housing in temporary pits and cages, including panthers and lynx, eagles and vultures, venomous snakes and lizards, and three different kinds of bears. (Animals were arriving with such frequency that Smithsonian officials hastily erected an ugly barn on the Mall to house a bull and cow, four deer, and a pair of buffalo.) Security was lax; wild dogs had already attacked a Rocky Mountain goat that was tied to a tree on the Mall, and would kill an antelope that Senator Leland Stanford had shipped from California.

Neither Glover’s optimism nor his commitment faltered. He turned his energy to convincing Congress of the park’s importance and took wavering representatives on tours of the land, all the while reminding them of the growing importance of Washington in the world. Like L’Enfant before him, Glover thought of the capital as a grand stage on which all the ideals of the republic would be seen by all the world. His persistence paid off. On the last Saturday of September in 1890, after the usual delays and speeches about the corruption and rapacious greed of Washington’s citizens, members of the 51st Congress approved a bill creating a “pleasuring ground” in the Rock Creek Valley. In 1892, the government acquired 1,600 acres on both sides of the winding creek above the National Zoo.

Rock Creek was not the only land in the capital that held Charles Carroll Glover’s interest. He had long wanted to reclaim the marshes in southwest Washington that citizens called the “Potomac Flats.” When L’Enfant had surveyed the site for his seat of government in 1791, the waters of the Potomac had covered the marshes between the White House and the river; the high tide of two feet served to keep the marshes passably fresh, and heavy rains often brought flooding, which sometimes extended inland as far as Pennsylvania Avenue. Over time, the city’s growth had changed the ecology even more. The Long Bridge of 1809, along with its earthen approach across the marsh, altered the river’s currents and tides; still John Quincy Adams thought the waters of the Potomac were clean enough to swim in when he was president. But the addition of sewers and a great discharge pipe at Seventeenth Street dumped the human waste of thousands directly into the river. Every summer the sewage created what one newspaper reporter called “a hellbroth” in the Potomac and a “miasma” in the air.

Most Washingtonians who could do so fled the city in the months of July and August. That had been James Garfield’s intent in July 1881, when he met Charles Guiteau. Instead the president spent the summer in the White House as doctors probed his body with dirty fingers and unsterilized instruments in their vain search for the bullet fragments that were slowly poisoning him. To cool the dying Garfield, military engineers rigged up fans in his bedroom that blew air over blocks of ice. The fans lowered the temperature but also drew in the putrescent stench from the Potomac Flats. It was in part the “evil effect of this poisonous atmosphere” that brought the question of reclamation of the flats to the fore.

That fall, Glover organized a group of citizens, including Crosby S. Noyes of the Washington Evening Star, to champion reclamation. Knowing Congress as Glover did, and knowing the opposition of many to any expenditure on the city, he moved in incremental steps. By 1882, Congress had approved enough funding, $400,000, to begin dredging a deeper channel in the Potomac. Silt from the river bottom served as fill to reclaim the marshes, and eventually army engineers erected a flood wall. By 1886, about 350 acres had been added to the Potomac waterfront, but a dispute over ownership of land near what is now the Lincoln Memorial, and the opposition of many in Congress, made progress for the next decade painfully slow.

And what was to be done with the new land? Some in Congress wanted to sell it for building lots. The railroads saw it as a great opportunity to build a huge siding, where roads from the North could meet those from the South. Glover thought otherwise. Working quietly with his friends in Congress, he promoted the idea of a great park. Congress defeated a park bill in 1895, but in late February 1897 it established the Potomac Park. Glover now used his easy entrée to the White House to lobby Grover Cleveland. On March 3, 1897, his last day in office, the president signed the bill.

Citizens with means and influence like Charles Carroll Glover could effect change in Washington. They were welcome at the homes of representatives, senators, cabinet members, even the White House. Many of them believed that life under three presidentially appointed commissioners was better than when the District was a territory. They remembered the brief time when those without property, including blacks, had enjoyed suffrage, and some had flirted with the notion of desegregating the schools. They were happy that the federal government and the District shared the city’s expenses equally. But as Washington and the government that dominated it grew in numbers and complexity, the impotence of the general populace became ever more apparent. District residents could not elect local representatives to tend to their interests in fundamental matters like streets, sanitation, or transportation; they could not elect someone to represent their interests in Congress; and they could not vote for presidential electors.

Over time, associations took the place of true representation. The first, the East Washington Citizens’ Association, formed in 1870 because, as its history noted, the city’s post–Civil War development was “leaning towards its western borders, and even the nurturing wave of Governmental care and appropriations seemed to be receding from the eastern half.” Membership was open to “any reputable citizen or taxpayer” who paid a fee of fifty cents. Nearly a score of similar associations followed, each advancing its own parochial interests to the commissioners, and on some occasions joining with others for the commonweal of the city.

Washington’s businessmen had created a Board of Trade in November 1889. Its membership grew quickly, reaching 655 by 1900. Prominent Jewish merchants belonged, as did James Wormley, who had succeeded his father as head of the Wormley House Hotel. (Starting in 1895, the board opened its membership to women.) In the absence of a municipal governmental structure, the bankers, realtors, lawyers, and department store owners who made up its board of directors formed the nucleus of the capital’s civic power structure. In its annual report for 1892, the Board of Trade proudly proclaimed itself “practically a state legislature, city council and chamber of commerce combined into one.”

Boards of trade, common in cities across America, were usually filled with proto-Babbit boosters. Washington’s board certainly had that role; it extolled the virtues of business in the capital and sent speakers into schools on patriotic days, such as Washington’s birthday. But from its inception, Washington’s board played a unique role, helping to supplement the insufficient and ineffective efforts of the three presidentially appointed commissioners and a largerly uninterested and overwhelmed Congress. Who would educate Congress about the inadequate fire department? About the need to improve the sewage system, and to fill in the abandoned canal in the southwest that had become such a pestilential sewer? About the importance of education and the value of a free public library?

The Board of Trade had a busy agenda. It set up committees to study numerous matters of importance to the District, including public safety, water purification, charities, and streets and avenues, among others. It advocated the removal of the B&O tracks and train station from the eastern edge of the Mall, and it fought the proposal from a Virginia railroad company that wished to lay tracks on the land being reclaimed at the Mall’s western end. Its aim, an early secretary said, was to make Washington the equal to Paris in beauty and attractions, to Rome in art, and to Berlin in education.

Theodore Williams Noyes, the son of Crosby and editor of the Washington Evening Star after his father’s death in 1908, disliked the present commission form of government. But he dismissed the idea of an elected limited municipal government that some proposed as a “sham”; without full representation, he said, Washington was shut out “from the bodies which make its laws and impose taxes upon it.” Starting in 1888, when he was associate editor, he frequently used the pages of the Star to advocate a constitutional amendment that would give the citizens the right to elect representatives to Congress as well as presidential electors. Few heeded Noyes’s call; Congress utterly ignored it. For decades, the issue of how to accord representation to the District’s citizens would continue to smolder beneath the scant platform of the city’s meager governmental structure—though, from time to time, a citizens group, a well-intentioned senator, or Noyes himself would attempt to coax the embers into flame.

Since much of its business was government, Washington appeared relatively isolated from the consequences of financial panics and depressions that sometimes beset the nation. However, one jobless man, Jacob Selcher Coxey, a populist from Massilon, Ohio, brought the depression of 1893 to the capital. Coxey organized an “army” to march east to the nation’s capital, where the men would demand that the government create a relief program that would pay them $1.50 for a day’s labor. On the last day of April in 1894, about four hundred men arrived at the Capitol steps, where guards promptly arrested Coxey for trespassing. The men quietly dispersed. Insignificant as the protest was, it augured a future role for the capital as the destination of choice for those who wanted to effect social change.

Throughout the 1890s, Washington’s white citizens remained generally cheerful and confident about their nation and their city. In 1900, William McKinley was reelected president with the largest margins ever in both the electoral college and the popular vote. Catching the wave of patriotic and religious fervor that came with the nation’s victory in the Spanish-American War, and taking credit for ending the economic depression of 1893, he rode on a platform of prosperity and the slogan “A Full Dinner Pail.” That December, the secretary of the treasury reported that the government had a surplus of $79 million. (An excise tax on telephone service had financed the war in Spain as well as the continuing fighting in the Philippines.) The American flag flying over the Capitol now had forty-five stars. In the wake of the war with Spain, Americans believed they had a “divine mission,” as Albert Jeremiah Beveridge, a young senator from Indiana, had put it. God had made Americans “the master organizers of the world to establish system where chaos reigns.” The decennial census showed that the population of the United States had reached 76.2 million. One of every thirteen families owned a telephone; one of every seven had indoor plumbing. America’s future was brighter than ever.

Washingtonians, too, embraced the nationalistic fervor. A regiment of volunteers had served gallantly in Cuba in the recent war. Its citizens had welcomed the hero of Manila Bay, Admiral George Dewey, in a grand ceremony when he returned home. Although they had been disenfranchised by Congress, had no control over their civic affairs, and no representatives in the federal government, they took an intense interest in politics and the presidential election. On the evening of November 6, the Washington Post had used lantern slides to show the results on a large screen outside its building; men with megaphones shouted out the latest news.

Washington’s white citizens were enjoying great prosperity. Real-estate prices and sales, already robust for the year, were experiencing a postelection surge; brokers reported they were “dickering with capitalists from Chicago, New York and other places” for choice properties; builders were busy erecting houses in the northwest, where building lots in Cleveland Park were trading for fifty cents per square foot; and Rhode Island Avenue, on the edge of LeDroit Park, was fast becoming a thoroughfare to the growing suburban tracts of Eckington and Edgewood in the northeast.

That December marked the opening of Washington’s season, which would extend through the winter months. “GAYETY IN FULL SWING,” proclaimed a typical headline in the Post. “Society Busy with Debutantes, Dinners and Receptions.” With the assistance of the wives of cabinet members, Mrs. McKinley and her husband had a reception for the ladies of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), which was holding its convention in the capital. (Although the WCTU ladies were unhappy that the president hadn’t banned serving liquor in army canteens, they appreciated his wife Ida’s firm stand against alcohol.) On Thursday the 13th, the city’s first automobile show at the convention hall culminated with a parade of electric, gas, and steam-powered cars, each bedecked with flowers, circling the hall. Washington’s theaters had a full complement of offerings, including the “Great Lafayette’s” vaudeville act at the New Grand; acrobats, pantomimists, and “a bevy of pretty girls” at the Columbia; and at the New National, Lottie Blair Parker’s melodrama Way Down East, which had just finished a year’s run in New York. On Friday evening, December 14, a former war correspondent, British army officer, and recently elected member of parliament lectured on the Boer War at the New National Theater. “[He] is not an orator,” wrote the reviewer for the next day’s paper. “He appeared embarrassed when he began, and throughout the lecture his words came out in a jerky halting way.” But in the peroration, Winston Churchill laid aside his embarrassment “and rose to the heights of eloquence.”

Surely the most important events that December for every one of the city’s 278,000 citizens, white or black, were the ceremonies marking Washington’s one-hundredth anniversary as the capital of the United States. They celebrated on Wednesday the 12th—a date chosen by the president—with an elaborate parade. The sky was bright and blue, the temperature was “balmy,” as the Evening Times described the day; all Washington was a “wilderness of flags and bunting.” Following McKinley and members of his cabinet up Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol were the nation’s forty-five governors (including Rhode Island’s, who rode with his staff in open automobiles), nine marching bands, and thousands of soldiers and sailors. That evening, after enduring three hours of speeches at the Capital and a reception at the Corcoran Gallery, Washingtonians saw their city aglow with light, including an American flag of red, white, and blue bulbs suspended over Pennsylvania Avenue at Seventeenth Street that “alternately brightened and paled,” to give the appearance of waving in the breeze.

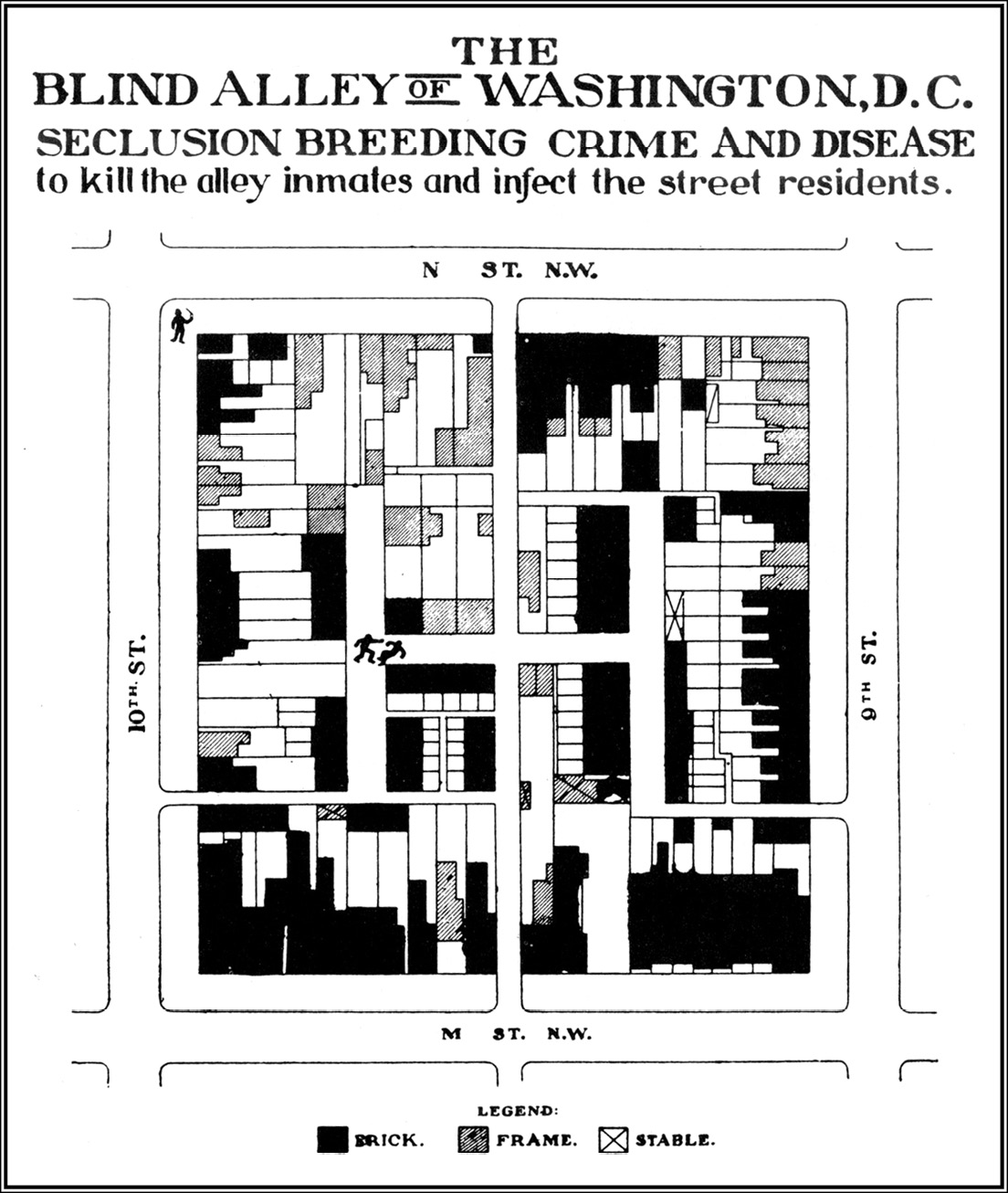

One group of Washingtonians, those who lived in Murder Bay and the alley dwellings, had but a marginal relationship with the centennial festivities. Alley dwellings, and those who lived in them, occupied a netherworld behind the houses that generally fronted on the lettered and numbered streets, and beneath the powerful who occupied them. (Eastman Johnson’s Negro Life at the Old South hints at their existence.) They were an unintended consequence of L’Enfant’s plan, which had created large square blocks that allowed developers to erect multiple houses. The division of streets made for neat blocks, but they allowed for a narrow passage to lead from the street into a dark, crowded interior, and frequently the passage ended in a blind. Typical of this time was Blagdon Alley. In 1890, about eighty houses occupied the square block bounded by M, N, Ninth, and Tenth streets. Narrow paths leading from each side of the block led to Blagdon, and no less than twenty alley dwellings, sheds really, with no running water and but the most primitive of privies.

Blagdon was but one of about two hundred alleys in the city, some with as many as five hundred dwellers. Some white immigrants lived in alley dwellings, but at the turn of the century blacks counted for most of the alley population. Many dwellers were the sons and daughters of freedmen who had migrated to the capital from the South. The conditions were horrendous. Tuberculosis flourished, as did outbreaks of cholera. Yet Congress refused to allow any District health officer to condemn the structures, and only in 1892 did District law begin to prevent the construction of new alley dwellings without running water and sewers. The law made no provision for the thousands already living there without such necessities. The alleys would continue.

Home to thousands of immigrants and blacks, the capital’s alleys seemed forbidding places to white middle-class Washingtonians. By placing the outline of a billy-club wielding policeman outside the alley and the fighters inside, the artist of this 1912 drawing is emphasizing the dangers of the lawlessness within. But the real danger was to the public health of the alley dwellers. Credit: Private collection

Still, despite the setbacks they experienced with the collapse of Reconstruction, as well as the discrimination they faced daily, Washington’s black citizens, especially its educated class, managed to retain a measure of pride against indignities and insults. The faculty at Howard University was almost entirely white, and of course the institution was led by a white man. McKinley had failed to appoint many blacks to civil service positions; political equality in a city that disenfranchised everyone was out of the question. Most indicative of the blacks’ treatment was their experience in the District of Columbia Militia. Since the 1870s, men and boys had marched in segregated battalions, drilling monthly and taking part in competitive military reviews. Only a protest to President Benjamin Harrison by the prominent black lawyer Robert Terrell, Frederick Douglass’s son Lewis, among others, prevented the commanding general from disbanding the black battalions altogether in 1891. A greater indignity followed in 1898, when another virulently anti-black commanding general forbade the “colored battalion” to fight in Cuba. Nevertheless, the black militiamen were able to circumvent the general’s orders and serve in Cuba as members of “immune companies,” soldiers whose skin color, it was erroneously thought, made them resistant to the ravages of yellow fever.

In the face of such obstacles, blacks still looked to education, self-discipline, and good works as the best way to advance. Representative George Henry White from North Carolina spoke to audiences at Washington’s black cultural societies, such as the Second Baptist Lyceum, of the “wonderful progress” that proved his race’s “capacity for development.” But those words marked the triumph of hope over the grim realities that surrounded him. White’s state, along with the rest of the South, had rewritten its constitution in 1900 to disenfranchise blacks. When he made his remarks, the congressman was in the final days of his term, a remnant of the late nineteenth century, the last black person from the South to serve in Congress until 1972.

But the troubles of black Washingtonians were of little matter to the city’s or the nation’s leaders. They were more concerned with the safety of the president. That same December, the papers carried reports of deranged men who had wanted to see McKinley. Guards apprehended one of them on the White House grounds after he said he wished to talk with the president about a $3 million pension that he claimed the government owed him. Another man, a tailor from Baltimore, declared that he was coming to a state dinner “in celebration of the reelection of the President.”

The annual Easter Egg Roll on the South Lawn of the White House has been a tradition since the time of the Hayes administration. Credit: Library of Congress

Both men were clearly insane, but then so was Charles Guiteau, who had murdered Garfield two decades earlier. Along with the insane, and perhaps Spanish Cubans, whom some feared would strike the president, there were now anarchists. It was rumored that the latter had drawn up a list of world leaders they would assassinate, and evidence from Europe substantiated just that. In April 1900, two shots from an anarchist’s gun had missed the prince of Wales; and in July an anarchist who had recently worked in Paterson, New Jersey, had murdered King Umberto I of Italy. Particularly worried for the president’s safety was his manager and sometime confidant Senator Mark Hanna from Ohio, who regarded Vice President Theodore Roosevelt as nothing more than a cowboy, once exclaiming, “Don’t any of you realize that there’s only one life between that madman and the Presidency?”

“There is only one National Capital. . . . There is only one incomparable residence city in the United States,” the Washington Board of Trade proclaimed in a pamphlet it published at the turn of the century. Washington was the best place on earth. Three commissioners operated the city, “completely devoid of dishonesty’s taint,” a system far better than the usual practice of “Board of Aldermen and a Common Council,” who regard “taxpayer’s contributions . . . as legitimate spoils.” The capital’s population was now approaching 300,000; its death rate was 19.32 per 1,000 souls (15.53 for whites and 27.51 for blacks). “Shallow wells have been filled up, marshes drained and streets cleaned, water-supply increased, milk carefully inspected, food adulterations sought and located, drainage stopped and sanitation taught.” The assessed value of new buildings in the previous year was nearly $2 million. New subdivisions were growing beyond the boundary set by L’Enfant, which afforded developers opportunities for profitable investment. Trains and steamboats linked the capital with Virginia and Maryland, and “all prominent suburbs” were “electrically connected to the city.”

As an educational center, the city offered the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian Institution, a chance to study “the government of the great republic”—and, the pamphlet noted, “one of every five-hundred inhabitants is a scientist of more than local repute.” With an “excellent” fire department and a police force that strove for “physical and mental fitness,” it said, “a mob in Washington is almost an impossibility.” Sports of all sorts were present in the capital: sailing, rowing, golf, and “an estimated fifty thousand bicycles” that could be “propelled over the smoothest of streets.” Even Washington’s weather came in for commendation. The city attracted many invalids in the fall who remained until they took to the mountains or seashore in the spring. Nevertheless, “in the summer it is much cooler than are many cities to the north of it. . . . The local record of sunstrokes and heat prostrations shows almost entire immunity from fatal cases.” Hyperbole aside, one truth was irrefutable: the thriving city of Washington had earned its place as the capital of the nation.