The Riemann Hypothesis is a mathematical statement that you can decompose the primes into music. That the primes have music in them is a poetic way of describing this mathematical theorem. However, it’s highly post-modern music. Michael Berry. University of Bristol

Riemann had found a passageway from the familiar world of numbers into a mathematics which would have seemed utterly alien to the Greeks who had studied prime numbers two thousand years before. He had innocently mixed imaginary numbers with his zeta function and discovered, like some mathematical alchemist, the mathematical treasure emerging from this admixture of elements that generations had been searching for. He had crammed his ideas into a ten-page paper, but was fully aware that his ideas would open up radically new vistas on the primes.

Riemann’s ability to unleash the full power of the zeta function stems from critical discoveries he made during his Berlin years and in his later doctoral studies in Göttingen. What had so impressed Gauss while he was examining Riemann’s thesis was the strong geometric intuition that the young mathematician showed when he was feeding functions with imaginary numbers. After all, Gauss had capitalised on his own private mental picture to map out these imaginary numbers before he dismantled the conceptual scaffolding. The starting point for Riemann’s theory of these imaginary functions had been Cauchy’s work, and for Cauchy a function was defined by an equation. Riemann had now added the idea that even if the equation was the starting point, it was the geometry of the graph defined by the equation that really mattered.

The problem is that the complete graph of a function fed with imaginary numbers is not something that is possible to draw. To illustrate his graph, Riemann needed to work in four dimensions. What do mathematicians mean by a fourth dimension? Those who have read cosmologists such as Stephen Hawking might well reply ‘time’. The truth is that we use dimensions to keep track of anything we might be interested in. In physics there are three dimensions for space and a fourth dimension for time. Economists who wish to investigate the relationship between interest rates, inflation, unemployment and the national debt can interpret the economy as a landscape in four dimensions. As they trek uphill in the direction interest rates, they will be exploring what happens to the economy in the other directions. Although we can’t actually draw a picture of this four-dimensional model of the economy, it is still a landscape whose hills and troughs we can analyse.

For Riemann, the zeta function was similarly described by a landscape that existed in four dimensions. There were two dimensions to keep track of the coordinates of the imaginary numbers being fed into the zeta function. The third and fourth dimensions could then be used to record the two coordinates describing the imaginary number output by the function.

The trouble is that we humans exist in three spatial dimensions and so cannot rely on our visual world for a perception of this new ‘imaginary graph’. Mathematicians have used the language of mathematics to train their mind’s eye to help them ‘see’ such structures. But if you lack such mathematical lenses, there are still ways to help you to grasp these higher-dimensional worlds. Looking at shadows is one of the best ways to understand them. Our shadow is a two-dimensional picture of our three-dimensional body. From some perspectives the shadow provides little information, but from side-on, for example, a silhouette can give us enough information about the person in three dimensions for us to recognise their face. In a similar way, we can construct a three-dimensional shadow of the four-dimensional landscape that Riemann built using the zeta function which retains enough information for us to understand Riemann’s ideas.

Gauss’s two-dimensional map of imaginary numbers charts the numbers that we shall feed into the zeta function. The north-south axis keeps track of how many steps we take in the imaginary direction, whilst the east-west axis charts the real numbers. We can lay this map out flat on a table. What we want to do is to create a physical landscape situated in the space above this map. The shadow of the zeta function will then turn into a physical object whose peaks and valleys we can explore.

The height above each imaginary number on the map should record the result of feeding that number into the zeta function. Some information is inevitably lost in the plotting of such a landscape, just as a shadow shows very limited detail of a three-dimensional object. By turning this object we get different shadows which reveal different aspects of the object. Similarly, we have a number of choices for what to record as the height of the landscape above each imaginary number in the map on the table top. There is, however, one choice of shadow which retains enough information to allow us to understand Riemann’s revelation. It is a perspective that helped Riemann in his journey through this looking-glass world. So what does this particular three-dimensional shadow of the zeta function look like?

As Riemann began to explore this landscape, he came across several key features. Standing in the landscape and looking towards the east, the zeta landscape levelled out to a smooth plane 1 unit high above sea level. If Riemann turned round and started walking west, he saw a ridge of undulating hills running from north to south. The peaks of these hills were all located above the line that crossed the east-west axis through the number 1. Above this intersection at the number 1 there was a towering peak which climbed into the heavens. It was, in fact, infinitely high. As Euler had learned, feeding the number 1 into the zeta function gives an output which spirals off to infinity. Heading north or south from this infinite peak, Riemann encountered other peaks. None of these peaks, however, were infinitely high. The first peak occurred at just under 10 steps north at the imaginary number 1 + (9.986 …) i and was only about 1.4 units high.

If Riemann turned the landscape around and charted the cross-section of the hills running along this north-south divide through the number 1, it would look something like this:

One crucial aspect of the landscape did not fail to attract Riemann’s attention. There appeared to be no way to use the formula for the zeta function to build the landscape out to the west beyond the range of mountains. Riemann had the same problem that Euler had experienced when feeding the zeta function with ordinary numbers. Whenever the input was a number west of 1, the formula for the zeta function spiralled off to infinity. Yet in this imaginary landscape, despite the infinite peak over the number 1, the other mountains along this north-south ridge looked passable.

Why did they not just continue undulating, irrespective of the zeta function’s results? Surely the landscape didn’t end there, at this north—south line. Was there really nothing to the west of this boundary? If you trusted only in the equations, you might believe that the landscape east of 1 was all that could be constructed. The equations didn’t make any sense when you put in numbers west of 1. Could Riemann complete the landscape, and if so, how?

Fortunately. Riemann wasn’t defeated by the seeming intractability of the zeta function. His education had armed him with a perspective that the French mathematicians lacked. He believed that the equation underlying an imaginary landscape should be regarded as a secondary feature. Of primary importance was the actual four-dimensional topography of the landscape. Although the equations may not make sense, the geometry of the landscape indicated otherwise. Riemann succeeded in finding another formula that could be used to build the missing landscape to the west. His new landscape could then be seamlessly joined onto the original landscape. An imaginary explorer could now pass smoothly from the region defined by Euler’s formula to the new landscape constructed by Riemann’s new formula without ever knowing there was a border crossing.

Riemann had a complete landscape which covered the entire map of imaginary numbers. He was now ready to make his next move. During his doctorate, Riemann had discovered two crucial and rather counterintuitive facts about these imaginary landscapes. First, he had learnt that they had an extraordinarily rigid geometry. There was only one way that the landscape could be expanded. The geometry of Euler’s landscape to the east completely determined what was possible out to the west. Riemann couldn’t massage his new landscape to create hills wherever he fancied. Any changes would cause the seam between the two landscapes to tear.

The inflexibility of these imaginary landscapes was a striking discovery. Once an imaginary cartographer has charted any small region of the imaginary landscape, that would be sufficient to reconstruct the rest of the landscape. Riemann had discovered that the hills and valleys in one region contain information about the topography of the complete landscape. This is certainly counter-intuitive. We would not expect a real-world cartographer, having charted the environs of Oxford, to be able to deduce the complete landscape of the British Isles.

But Riemann had made a second crucial discovery about this strange new brand of mathematics. He had uncovered what could be considered the DNA of these imaginary landscapes. Any mathematical cartographer who knew how to plot on the two-dimensional imaginary map the points where the landscape fell to sea level could reconstruct everything about the entire landscape. The map marking these points was the treasure map of any imaginary landscape. It was a stunning discovery. A cartographer living in our real world wouldn’t be able to reconstruct the Alps if you told him all the coordinates of points at sea level around the world. But in these imaginary landscapes the location of all the imaginary numbers where the function outputs zero told you everything. These places are called the zeros of the zeta function.

Astronomers are quite used to being able to deduce the chemical make-up of far-away planets without ever visiting them. The light they emit can be analysed by spectroscopy and contains enough information in it to reveal the chemistry of the planet. These zeros behave like the spectrum emitted by a chemical compound. Riemann knew that all he needed to do was to mark out all the points in the map where the height of the complete zeta landscape was zero. The coordinates of all these points at sea level would give him enough information to reconstruct all the hills and valleys above sea level.

Riemann did not forget where all his exploring had started. The big bang that had created this zeta landscape had been Euler’s formula for the zeta function, which could be built out of the primes by using Euler’s product. If the two things – prime numbers and the zeros – built the same landscape, Riemann knew there had to be some connection between them. One object built in two ways. It was Riemann’s genius that revealed how these two things were two sides of the same equation.

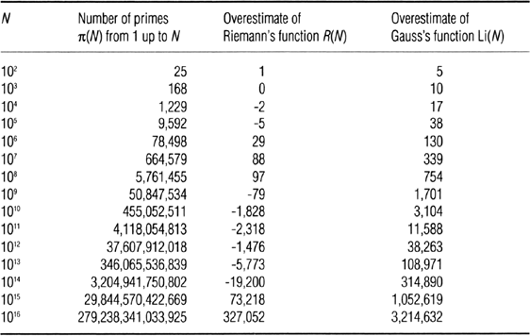

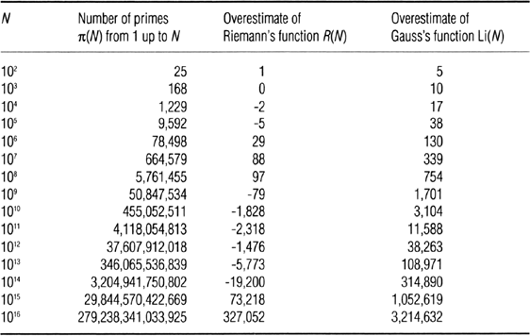

The connection that Riemann managed to find between prime numbers and the points at sea level in the zeta landscape was about as direct as one could hope for. Gauss had tried to estimate how many primes there were in the numbers from 1 through to any number N. Riemann, though, was able to produce an exact formula for the number of primes up to N by using the coordinates of these zeros. The formula that Riemann concocted had two key ingredients. The first was a new function R(N) for estimating the number of primes less than N which substantially improved on Gauss’s first guess. Riemann’s new function was, like Gauss’s, still producing errors, but Riemann’s calculations revealed that his formula gave significantly smaller errors. For example, Gauss’s logarithmic integral predicted 754 more primes than there were up to 100 million. Riemann’s refinement predicted only 97 more an error of roughly one-thousandth of 1 per cent.

The table overleaf shows how much more accurate Riemann’s new function is at guessing the number of primes up to N for values of N from 102 to 1016.

Riemann’s new function had improved on Gauss but it was still producing errors. Nevertheless, his trip into the imaginary world gave him access to something that Gauss could never have dreamed of – a way to undo these errors. Riemann realised that by using the points in the map of imaginary numbers that marked the places where the zeta landscape was at sea level, he could get rid of these errors and produce an exact formula counting the number of primes. This would be the second key ingredient in Riemann’s formula.

Euler had made the surprising discovery that feeding an imaginary number into the exponential function produced a sine wave. The rapidly climbing graph usually associated with the exponential function had been transformed by the introduction of these imaginary numbers into an undulating graph of the type more often associated with sound waves. His discovery sparked a rush to explore the strange connections thrown up by these imaginary numbers. Riemann could see that there was a way to extend Euler’s find by using his map marking the zeros in the imaginary landscape. In this looking-glass world, Riemann saw how each of these points could be transformed using the zeta function into its own special wave. Each wave would look like a variation on the graph of an undulating sine function.

The character of each wave was determined by the location of the zero responsible for the wave. The farther north the point at sea level, the faster the wave corresponding to this zero would oscillate. If we think of this wave as a sound wave, the note corresponding to a zero sounds higher the farther north the zero is located in the zeta landscape.

Why were these waves or notes helpful for counting primes? Riemann made the stunning discovery that encoded in the varying heights of these waves was the way to correct the errors in his guess for the number of primes. His function R(N) gave a reasonably good count of the number of primes up to N. But by adding to this guess the height of each wave above the number N, he found he could get the exact number of primes. The error had been eliminated completely. Riemann had unearthed the Holy Grail that Gauss had sought: an exact formula for the number of primes up to N.

The equation expressing this discovery can be summed up in words simply as ‘primes = zeros = waves’. Riemann’s formula for the number of primes in terms of zeros is as dramatic to a mathematician as Einstein’s equation E = mc2 that revealed the direct relationship between mass and energy. Here was a formula of connections and transformations. Step by step, Riemann witnessed the primes metamorphose. The primes create the zeta landscape, and the points at sea level in this landscape are the key to unlocking its secrets. A new connection then emerges whereby each of these points at sea level produces a wave, like a musical note. And finally, Riemann came full circle to show how these waves could be used to count primes. Riemann must have been amazed as he completed the circle in such a dramatic fashion.

Riemann knew that, just as there are infinitely many primes, there are infinitely many points at sea level in the zeta landscape. So there are correspondingly infinitely many waves controlling the errors. There is a very graphic way to see how the addition of each extra wave improves Riemann’s formula for the number of primes. Before adding the waves corresponding to zeros, the graph of Riemann’s function R(N) (depicted overleaf on the top) doesn’t look anything like the staircase counting the number of primes (on the bottom). One is smooth, the other jagged.

Even just adding the errors predicted by the first thirty waves created by the first thirty zeros we encounter when we head north in the landscape has a dramatic effect. Riemann’s graph has already transformed itself from the smooth graph corresponding to R(N) and is beginning to look much more like the staircase graph describing the number of primes (see page 93).

Each new wave contorts the smooth graph that little bit more. Riemann realised that by the time you added on the infinite number of waves, one for each point at sea level he encountered as he headed north across the zeta landscape, the resulting graph would be an exact match for the prime number staircase.

A generation before. Gauss had discovered what he believed was the coin that Nature had tossed to choose the primes. The waves that Riemann had discovered were the actual results of Nature’s tosses. The heights of each of these waves at the number N would predict at each toss whether the prime number coin landed heads or tails. Whilst Gauss’s discovery of the connection between primes and logarithms had predicted how the primes behave on average, Riemann’s had found what controlled the minute details of the primes. Riemann had uncovered a record of the winning prime number lottery tickets.

For centuries, mathematicians had been listening to the primes and hearing only disorganised noise. These numbers were like random notes wildly dotted on a mathematical stave, with no discernible tune. Now Riemann had found new ears with which to listen to these mysterious tones. The sine-like waves that Riemann had created from the zeros in his zeta landscape revealed some hidden harmonic structure.

Pythagoras had unveiled the musical harmony hidden in a sequence of fractions by banging his urn. Mersenne and Euler, both masters of the primes, were responsible for the mathematical theory of harmonics. But none of them had any inkling that there were direct connections between music and the primes. It was a music that required nineteenth-century mathematical ears to hear it. Riemann’s imaginary world had thrown up simple waves that together could reproduce the subtle harmonies of the primes.

One mathematician above all others would have been able to see how Riemann’s formula captured the hidden music of the primes: Joseph Fourier. An orphan, Fourier had been educated in a military school run by Benedictine monks. A wild child until the age of thirteen, he became entranced by mathematics. Fourier had been destined for a life as a monk, but the events of 1789 released him from the expectations that pre-Revolutionary life had imposed on him. Now he could indulge his passion for mathematics and the military.

Fourier was a great enthusiast of the Revolution, and soon came to the notice of Napoleon. The emperor was setting up the academies that were to turn out the teachers and engineers who would bring about his cultural and military revolution. Napoleon, recognising Fourier’s exceptional abilities not only as a mathematician but also as a teacher, appointed him to take charge of mathematical education at the École Polytechnique.

Napoleon was so impressed by what his protégé achieved that he made Fourier part of the Legion of Culture set up to ‘civilise’ Egypt following the French invasion of 1798. The expedition was driven by Napoleon’s desire to disrupt Britain’s growing colonial supremacy, but the opportunity to study the ancient world was also on his agenda. His army of intellectuals were put to work as soon as they had boarded Napoleon’s flagship L’Orient on its way to North Africa. Every morning Napoleon would announce the subject he expected his academic ambassadors to entertain him with that evening. As sailors laboured over rigging and sails, below the decks Fourier and his colleagues wrestled with a variety of Napoleon’s pet interests, ranging from the age of the Earth to the question of whether the other planets are inhabited.

On arrival in Egypt, not everything went to plan. Having taken Cairo by force at the Battle of the Pyramids in July 1798, Napoleon was disappointed to find that the Egyptians did not seem to appreciate the cultural force-feeding served up by the likes of Fourier. When three hundred of his men had their throats cut during an evening brawl, Napoleon decided to cut his losses and return to the turmoil that was brewing back in Paris. He set off without telling any of his intellectual army that he was abandoning them. Fourier, left stranded in Cairo, didn’t have sufficient rank to take to his heels without risking being shot for desertion and was forced to stay on in the desert. He managed to return to France in 1801, after the French had decided to leave the ‘civilising’ of Egypt in the hands of the British.

While he was in Egypt, Fourier developed an addiction to the searing heat of the desert. Back in Paris he kept his rooms so hot that friends compared them to the furnaces of hell. He believed that extreme heat helped keep the body healthy and even cured some diseases. His friends would find him wrapped up like an Egyptian mummy, sweating in a room that was as hot as the Sahara.

Fourier’s predilection for heat extended to his academic work. He earned his place in the history of mathematics for his analysis of the propagation of heat, work described by the British physicist Lord Kelvin as ‘a great mathematical poem’. Fourier had been spurred on in his efforts after the Academy in Paris announced that it would offer its Grand Prix des Mathématiques in 1812 to whoever could unravel the mysteries of how-heat moved through matter. Fourier was awarded the prize in recognition of the novelty and importance of his ideas. But he also had to swallow some criticism of his work from, among others, Legendre. The judges of the Grand Prix pointed out that much of his treatise contained mistakes and his mathematical explanation was far from rigorous. Fourier deeply resented the Academy’s critique but recognised that there was still work to be done.

As he set out to correct the errors in his analysis, Fourier tried to understand the nature of graphs representing physical phenomena – for example, the graph that showed how temperature evolved over time, or the graph representing a sound wave. He knew that sound could be represented by a graph where the horizontal axis charts time and the vertical axis controls the volume and pitch of the sound at each instant.

Fourier started with a graph of the simplest sound. If you set a tuning fork vibrating, you find when you plot the resulting sound wave that it is a pure, perfect sine curve. Fourier began to explore how more complicated sounds could be produced by taking combinations of these pure sine waves. If a violin plays the same note as the tuning fork, the sound is very different. As we have seen (see p. 78), the violin string doesn’t just vibrate at the fundamental frequency, determined by the length of the string. There are additional notes, the harmonics, which correspond to simple fractions of the length of the string. The graphs of each of these additional notes are still sine waves, but of higher frequencies. It is the combination of all these pure notes, dominated by the lowest, fundamental note, that creates the sound of a violin, whose graph looks like the teeth on a saw.

Why does a clarinet sound so characteristically different to the sound of a violin playing the same note? The graph of the sound wave created by the clarinet looks like a square wave function, like the crenellation on the top of a castle wall, instead of the spiky graph of the violin. The reason for the difference is that the clarinet is open at one end, whereas the string in the violin is fixed at both ends. This means that the harmonics produced by the clarinet vary from those of the violin, so the graph depicting the sound of the clarinet is built from sine waves oscillating at different frequencies.

Fourier realised that even the complicated graph depicting the sound of an entire orchestra could be broken down into simple sine curves of the fundamental and harmonics for each and every instrument. Since each of the pure sound waves can be reproduced by a tuning fork, Fourier had proved that by playing a huge number of tuning forks simultaneously you could create the sound of a whole orchestra. Someone with a blindfold on would not be able to tell whether it was a real orchestra or thousands of tuning forks. This principle is at the heart of how sound is encoded on a CD: the CD instructs your speakers how to vibrate to create all the sine waves that make up the sound of the music. This combination of sine waves gives you the miraculous sensation of having an orchestra or a band performing live in your living room.

It wasn’t only the sound of musical instruments that could be reproduced by adding together pure sine waves with different frequencies. For example, the static white noise created by an untuned radio or a running tap can be represented as an infinite sum of sine waves. In contrast to the distinct frequencies required to reproduce the sound of the orchestra, white noise is built from a continuous range of frequencies.

Fourier’s revolutionary insights went beyond reproducing sound alone. He began to understand how to use sine waves to plot graphs that depicted other physical or mathematical phenomena. Many of Fourier’s contemporaries doubted that such a simple graph as the sine wave could be used as a building block to construct complicated graphs of the sound of an orchestra or a running tap. In fact, a number of senior mathematicians in France voiced their vigorous opposition to Fourier’s ideas. Emboldened, however, by his prestigious association with Napoleon, Fourier did not fight shy of challenging the authorities. He showed how an appropriate selection of sine waves oscillating at different frequencies could be used to create a whole range of complicated graphs. By adding the heights of the sine waves you could reproduce the shapes of these graphs, in just the same way that a CD combines the pure tones of tuning forks to reproduce complex musical sounds.

This is precisely what Riemann succeeded in doing in that ten-page paper. He reproduced the staircase graph that counted the number of primes in exactly the same fashion by adding together the heights of the wave functions he derived from the zeros in the zeta landscape. This is why Fourier would have recognised Riemann’s formula for the number of primes as the discovery of the basic tones that make up the sound of the primes. This complicated sound is represented by the staircase graph. Riemann’s waves that he created from the zeros, the points at sea level in the landscape, were like the sounds of tuning forks, single clear notes with no harmonics. When played simultaneously these basic waves reproduced the sound of the primes. So what does Riemann’s prime number music sound like? Is it the sound of an orchestra, or does it resemble the white noise of a running tap? If the frequencies of Riemann’s notes are in a continuous range, then the primes make white noise. But if the frequencies are isolated notes, then the sound of the primes resembles the music of an orchestra.

Given the randomness of the primes, we might well expect the combination of notes played by the zeros in Riemann’s landscape to be nothing more than noise. The north—south coordinate of each zero determines the pitch of its note. If the sound of the primes were indeed white noise, there would have to be a concentration of zeros in the zeta landscape. And Riemann knew, from his dissertation for Gauss, that such a concentration of points at sea level would actually force the whole of the landscape to be at sea level. This clearly wasn’t the case. The sound of the primes was not white noise at all. The points at sea level had to be isolated points, so they had to produce a collection of isolated notes. Nature had hidden in the primes the music of some mathematical orchestra.

What Riemann had done was to take each of the points on the map of the imaginary world that sat at sea level. Out of each point he had created a wave, like a note from some mathematical instrument. By combining all these waves, he had an orchestra that played the music of the primes. The north—south coordinate of each point at sea level controlled the frequency of the wave – how high the corresponding note sounded. In contrast, the east—west coordinate controlled, as Euler had learnt, how loud each note would be played. The louder the note, the larger the fluctuations of its undulating graph.

Riemann was intrigued to know whether any of the zeros were playing significantly louder than the others. Such a zero would produce a wave whose graph was fluctuating higher than the other waves and hence would play a bigger part in counting the primes. After all, it is the heights of these waves that control the difference between Gauss’s guess and the true number of primes. Was there some instrument in this prime number orchestra that was playing a solo above the sound of the others? The farther east a point at sea level was located, the louder the note would be. To determine the balance of the orchestra, Riemann had to go back and look at the coordinates of each of the zeros in his imaginary map.

Remarkably, so far his analysis had worked without him having to know the locations of any of the points at sea level. He knew that there were some zeros that stretched out to the west which were easy to locate, but they contributed nothing interesting to the sound of the primes because they had no pitch. In their dismissive manner, mathematicians would later call these the trivial zeros. It was the location of the remaining zeros that Riemann was after.

As he began to explore the precise location of these points, he got a big surprise. Instead of being randomly dotted around the map, making some notes louder than others, the zeros he calculated seemed to be miraculously arranged in a straight line running north—south through the landscape. It appeared as if every point at sea level had the same east—west coordinate, equal to ![]() . If true, it meant that the corresponding waves were perfectly balanced, none performing louder than any other.

. If true, it meant that the corresponding waves were perfectly balanced, none performing louder than any other.

The first zero that Riemann calculated had coordinates (![]() , 14.134725 …): you head east

, 14.134725 …): you head east ![]() step, and north about 14.134 725 steps. The next zero had coordinates (

step, and north about 14.134 725 steps. The next zero had coordinates (![]() , 21.022040 …). (How he managed to calculate the location of any of these zeros remained a mystery for years.) He calculated a third zero which was located at (

, 21.022040 …). (How he managed to calculate the location of any of these zeros remained a mystery for years.) He calculated a third zero which was located at (![]() , 25.010856…). These zeros did not appear to be scattered at random. Riemann’s calculations indicated that they were lining up as if along some mystical ley line running through the landscape. Riemann speculated that the regimented behaviour of the few zeros he was able to calculate was no coincidence. His belief that every point at sea level in his landscape would be found on this straight line is what has become known as the Riemann Hypothesis.

, 25.010856…). These zeros did not appear to be scattered at random. Riemann’s calculations indicated that they were lining up as if along some mystical ley line running through the landscape. Riemann speculated that the regimented behaviour of the few zeros he was able to calculate was no coincidence. His belief that every point at sea level in his landscape would be found on this straight line is what has become known as the Riemann Hypothesis.

Riemann looked at the image of the primes in the mirror that separated the world of numbers from his zeta landscape. As he watched, he saw the chaotic arrangement of the prime numbers on one side of the mirror transform into the strict regimented order of the zeros on the other side of the mirror. Riemann had finally found the mysterious pattern that centuries of mathematicians had been yearning to see as they stared at the primes.

The discovery of this pattern was totally unexpected. Riemann was lucky to be the right person in the right place at the right time: he could not have anticipated what was awaiting him on the other side of the looking-glass. But what lay there completely transformed the task of understanding the mysteries of the primes. Now mathematicians had a new landscape to explore. If they could navigate the land of the zeta function and chart the places at sea level, the primes might yet yield their secrets. What Riemann had also discovered was evidence of some ley line running through this landscape whose significance runs to the very heart of mathematics. The importance of Riemann’s ley line can be judged by the name by which mathematicians now refer to it – the critical line. Suddenly, the puzzle of the randomness of the primes in the real world has been replaced by the quest to understand the harmony of this imaginary looking-glass landscape.

Since there are an infinite number of zeros, the few scraps of evidence that Riemann had discovered seem quite precarious facts on which to base a theory. All the same, Riemann knew that this ley line had an important significance. He already knew that the east – west axis represented a line of symmetry for the zeta landscape. Anything that happened to the north would be reflected by the same behaviour to the south. Riemann had further discovered the much more significant fact that this line running north—south through the point at ![]() was also an important line of symmetry. This might well have given Riemann cause to believe that Nature would also have used this line of symmetry to order the zeros.

was also an important line of symmetry. This might well have given Riemann cause to believe that Nature would also have used this line of symmetry to order the zeros.

What is so extraordinary about the events surrounding Riemann’s major discovery is that his calculations of the locations of the first few zeros did not appear anywhere in the dense paper about prime numbers he wrote for the Berlin Academy. In fact, one is hard pushed to find any statement of this discovery in his published paper. He writes that many of the zeros appear on this straight line, and that it is ‘very likely’ that all of them do. But Riemann admits in this paper that he didn’t try too hard to prove his Hypothesis.

After all, Riemann was after the much more immediate goal of proving Gauss’s Prime Number Conjecture: to show why Gauss’s guess for the primes became more accurate the more primes one counted. Although this proof also remained elusive, Riemann realised that if his hunch about this ley line were true then it would imply that Gauss had indeed been right. As Riemann had discovered, the errors in Gauss’s formula could be described by the location of each of the zeros. The farther east a zero, the louder the wave. The louder the wave, the bigger the error. This is why Riemann’s prediction about the location of the zeros was so important to mathematics. If he was right, and the zeros did all lie on his magic ley line, it would imply that Gauss’s guess would always be incredibly accurate.

The publication of his ten-page paper marked a brief period of happiness for Riemann. He was honoured with the chair that his mentors Gauss and Dirichlet had both occupied. His sisters had joined him in Göttingen after his brother, who had been supporting them, died in 1857. It boosted Riemann’s morale to have his family close by, and he was less prone to the bouts of depression that he had suffered in previous years. With the salary of a professor, he no longer had to endure the poverty of his student years. And at last he could afford proper lodgings and even a housekeeper so that he could dedicate his time to pursuing the ideas that were dancing around in his head.

Yet he was never to return to the subject of prime numbers. He went on to follow his geometric intuition and developed a notion of the geometry of space which was to become one of the cornerstones of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. This period of good fortune culminated in 1862 in his marriage to Elise Koch, a friend of his sisters. But barely a month later he fell ill with pleurisy. From then on, ill health was to plague him constantly, and on many occasions he sought refuge in the Italian countryside. He became particularly attached to Pisa, which was where in August 1863 his only child, Ida, was born. Riemann enjoyed his trips to Italy not just for the clement weather but also for the intellectual climate he encountered; in his lifetime it was the Italian mathematical community that was most receptive to his revolutionary ideas.

His last visit to Italy was an escape not from the dank atmosphere of Göttingen but from an invading army. In 1866 the armies of Hanover and Prussia clashed in Göttingen. Riemann found himself stranded in his lodgings – Gauss’s old observatory, outside the city walls. Judging by the state in which he left the place, Riemann fled in a hurry to Italy. The shock proved too much for his frail constitution. Seven years after the publication of his paper on the primes, Riemann died from consumption, aged only thirty-nine.

Faced with the mess Riemann left behind, his housekeeper destroyed many of his unpublished scribblings before she was stopped by members of the faculty in Göttingen. The remaining papers were handed over to Riemann’s widow and disappeared for years. It is intriguing to speculate what might have been found if his housekeeper had not been so keen to clear his study. One statement which Riemann made in his ten-page paper indicates that he believed he could prove that most zeros are on his ley line. His perfectionism stopped him from elaborating, and he wrote simply that his proof was not yet ready for publication. The proof was never found amongst his unpublished papers, and to this day mathematicians haven’t been able to reproduce one. Those missing pages of Riemann’s are as provocative as Fermat’s claim to have had a proof of his Last Theorem.

Some unpublished notes that did survive the housekeeper’s fire resurfaced after fifty years. Frustratingly, they indicate that Riemann had indeed proved much more than he published. Sadly, though, many of the papers detailing results that he tantalisingly hinted he had some understanding of have probably been lost for eternity in the kitchen fire of his overzealous housekeeper.