On September 21 General Franks, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) General Hugh Shelton, Vice CJCS General Dick Myers, and JSOC commander Major General Dell Dailey briefed President Bush and Vice President Cheney on a four-phase operations plan:

Phase I: Set conditions and build forces to provide the National Command Authority credible military options: build alliances and prepare the battlefield.

Phase II: Conduct initial combat operations and continue to set conditions for follow-on operations; begin initial humanitarian operations.

Phase III: Conduct major combat operations in Afghanistan, continue to build coalition, and conduct operations.

Phase IV: Establish capability of coalition partners to prevent the re-emergence of terrorism and establish support for humanitarian operation: expected to be a 3–5 year effort.1

In addition to complex internal tribal alliances, the geography of Afghanistan presents formidable geographic obstacles to any invader. This land-locked country is roughly the size of Texas. It is a land of towering mountain ranges and remote valleys in the north and east, and near desert-like conditions on the plains to the south and west. Road and rail communication nets are minimal and in disrepair. The rough terrain poses major logistical challenges to any military effort. All supplies and personnel have to be either flown or trucked in. Mountainous routes along the Afghanistan–Pakistan border provide excellent locations for mines and ambushes. Throughout the winter many passes, including the crucial northern routes through the Hindu Kush from Tajikistan to Kabul, are choked off by snow. Mountains in the north are too high for helicopters to operate in, while throughout the country dust-induced “brown outs” flare up unexpectedly, blinding pilots. Mountains and deep valleys block radio transmissions. Extremes of heat and cold stress both equipment and personnel. It is a feudal land populated by Pashtuns (the ethnic majority), Hazaras, Kaffirs, Tajiks, and Uzbeks among others, many members of which are illiterate. It is a place that in many ways has not changed in several millenia. The history, terrain, and fiercely independent people of Afghanistan present major challenges to any invader.

Initially, Pentagon officials labeled the impending campaign Operation Infinite Justice. Later, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld abandoned that code name after Islamic scholars objected on the asserted grounds that only God could impose “infinite justice.”

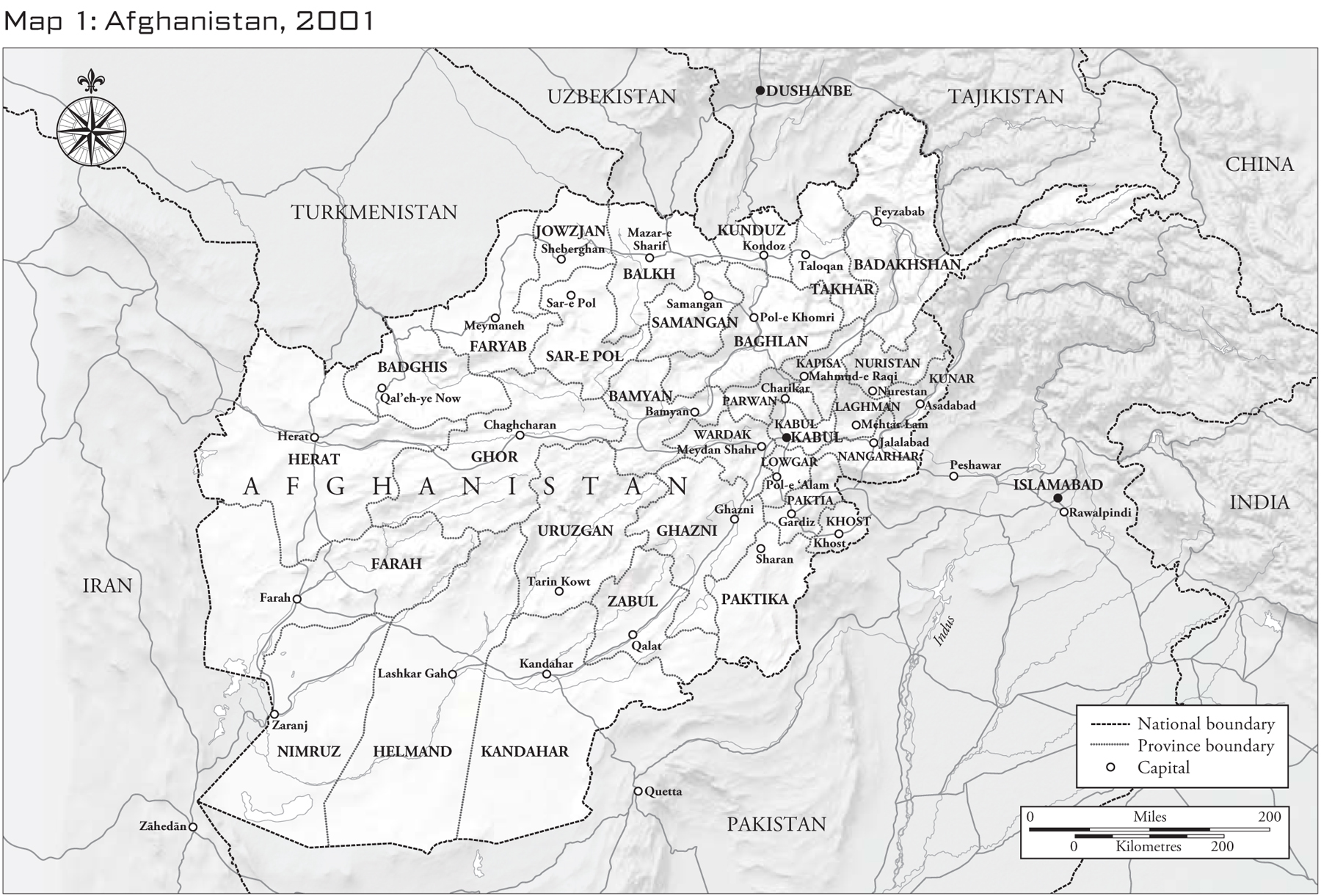

Planning for the strikes would take time to set up. There were (and still are) only two ways of getting the necessary assets in place to conduct operations. The first is from the south through Pakistan. Materiel could either be landed by ship in ports on the Arabian Sea and then trucked north, or flown into Islamabad and then trucked through the passes into Afghanistan. From the north, airbases in either the former Soviet republics of Turkmenistan or Uzbekistan were the only options. Of these two, Uzbekistan was the best choice. There was an old Soviet airbase at Karshi-Khanabad (K2), which provided a starting point. It was also attractive because of its proximity to Afghan Northern Alliance forces.2 (See Map 1.) Although it was in place, K2 needed significant work to be usable.

The plan was for US and coalition forces to concentrate on destroying al Qaeda’s organization and persuading or forcing other nations and non-states to stop supporting terrorists. Concurrently, armed forces were to support humanitarian operations to convince the Afghans and the Islamic world that the war was not directed at them. At this point the US military was not to participate in nation building.3

The initial stages of the war in Afghanistan were to be fought by the Northern Alliance with support from integrated Special Forces and US Air Force ground and air elements. The concept of the operation was to insert Special Forces teams first into the northern areas of Mazar-e Sharif and Bagram–Kabul, followed almost simultaneously by insertions into the Kunduz–Taloqan region. These combined forces were to establish a foothold in northern Afghanistan and drive the Taliban and al Qaeda forces into Kabul.

Once these areas were secured, the plan was to move teams south to liberate Kandahar, the center of the Taliban movement. Then the focus would shift to a likely area of enemy concentration in the extensive Tora Bora cave complex situated in the White Mountains of eastern Afghanistan, near the Khyber Pass.

The in-theater commander of Special Forces was the CENTCOM Combined Forces Special Operations Component Command, led by Rear Admiral Albert M. Calland III, who reported directly to General Franks.

Rear Admiral Calland established two joint special operation task forces (JSOTF), which separately covered north and south Afghanistan. The JSOTF North, called Task Force (TF) Dagger, was commanded by Colonel John Mulholland, and was formed around the 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne). This group would engage in classic unconventional warfare, working directly with native forces. It waited at K2 base until Uzbekistan announced that it was offering humanitarian assistance and Combat Search and Rescue (CSAR). Special Forces teams, under Major General Dell Dailey, included in JSOTF North and commanded by Colonel Frank Kisner, were responsible for CSAR.

JSOTF South (TF 11) was built around a two-squadron component of Special Mission Unit (SMU) operators from the Combat Applications Group and the Naval Special Warfare Development Group (DEVGRU [SEALs]), supported by Ranger security teams, and intelligence specialists from the Intelligence Support Agency (code named Grey Fox), NSA, and the CIA. TF Sword concentrated on gathering intelligence, conducting operations against sensitive sites, and eliminating individual terrorist threats.4, 5

Task Force K-Bar, a component of TF 11, and consisting mostly of Navy SEALs along with foreign Special Forces, and elements of the 3rd Special Forces Group (Airborne) under the command of Navy Captain Robert Howard, set up operations in Oman.6 TF K-Bar was tasked with conducting anti-smuggling missions, including interdiction of vessels in the Arabian Gulf suspected of carrying arms that would be offloaded in remote areas of the Pakistani coast, and reconnaissance missions involving the insertion of teams throughout southern Afghanistan. A major part of TF K-Bar’s work was Sensitive Site Exploitation – the surveillance and raiding of locations in southern Afghanistan suspected of containing al Qaeda or senior Taliban individuals, arms, and intelligence materials.7, 8

Although there were US air assets based around the Persian Gulf enforcing the “No Fly Zone” over southern Iraq as part of Operation Southern Watch, none had the legs to reach Afghanistan without mid-air refueling going both ways. Also, the bases themselves had to be upgraded to sustain the increased traffic.

On September 26, two weeks before ground operations began, the first seven-man CIA Northern Afghanistan Liaison Team (NALT) (code named Jawbreaker), led by Gary Schroen, flew into the Panjshir Valley north of Kabul to establish working relationships with Tajik generals Fahim Khan and Bismullah Khan, and the overall Northern Alliance military forces. Millions of dollars in cash was given to Northern Alliance leaders, which was used to purchase weapons and supplies. The team’s tasks included ensuring Northern Alliance cooperation with the planned US invasion, collecting intelligence on the location of Taliban and al Qaeda leaders, locating al Qaeda training camps, and mapping frontline positions of the Taliban for later use in air strikes.9

At 1:00pm Eastern Time, Sunday, October 7, 2001, President Bush spoke to the nation on live television from the White House: “On my orders, the United States military has begun strikes against al Qaeda terrorist training camps and military installations of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan.”

Operation Crescent City opened the air war with strikes by F-14 and F/A-18 carrier-based fighters from Carl Vinson (CVN 70) and Enterprise (CVN 65), Air Force land-based B-1, B-2, and B-52 bombers, and BGM-109 TLAM launched from US and British submarines. The massed attack struck targets such as aircraft on the ground, airfields, antiaircraft and surface-to-air missile batteries and radar sites, command-and-control nodes, and terrorist training camps. Critics questioned the raids on the camps because al Qaeda had largely abandoned the facilities, but the assaults destroyed terrorist infrastructure.10 Air Force F-15E and F-16 fighters joined the fray, flying missions from bases on the Persian Gulf.

On October 9, Commando Solo, EC-130, from the Pennsylvania Air National Guard 193rd Special Operations Wing headed east to Afghanistan from its base on the Persian Gulf. Commando Solo was equipped with nine radio transmitters and a special 300ft drogue antenna extended from the plane’s underbelly. The five-man crew consisted of a commercial pilot, a police officer, a machine-shop owner, an electrical engineer, and a social worker.

Moments later, a transmitter crackled to life and broadcast a message to the enemy combatants below in their native tongue:

Attention Taliban! You are condemned. Did you know that? The instant the terrorists you supported took over our planes, you sentenced yourselves to death. The armed forces of the United States are here to seek justice for our dead. Highly trained soldiers are coming to shut down once and for all Osama bin Laden’s ring of terrorism and the Taliban that supports them and their action. When you decide to surrender, approach United States forces with your hands in the air. Sling your weapon across your back, muzzle towards the ground. Remove your magazine and expel any rounds. Doing this is your only chance of survival.11

Although the US established ties with Tajik leaders in the north, these men would not be acceptable leaders to Afghanistan’s Pashtun population. This need for Pashtun leadership was filled by two well-known Pashtun opponents of the Taliban regime: the expatriate Hamid Karzai and Gul Agha Sherzai, who had been hiding in Afghanistan. Both men had fought the Soviets and both had experience from their post-Soviet government positions when the Taliban came to power.

Karzai entered Afghanistan from Pakistan on October 8–9. Over the next three weeks he met with local leaders and managed to assemble a small, 50-man force. He used his satellite telephone to call the US consulate and ask for support. Within 48 hours large amounts of weapons and supplies were parachuted to him. In addition to arms, Karzai requested US advisers. These were provided by Operation Detachment Alpha (ODA) 574 on November 14.12

For Master Sergeant Dale G. Aaknes, 5th Special Forces Group, working with the logistics needed to launch the war from K2 proved to be a nightmare. In addition to food, water, clothing, and ammunition he had to find items that had not been ordered by anyone in Army for decades:

We started to get requests for horse and animal feed. I never realized how many different kinds of feed there are. The problem being reported is that the animals were getting sick on the feed we shipped. We found out that the oats we shipped were a better quality than what they were used to, this caused the horses to get sick. To fix the problem we shipped the lowest quality oats I could find. The next little problem was the availability of horse saddles. We knew absolutely nothing about saddles, so we had to get some help. Our group comptroller’s wife was a horse person. I called her and asked her to purchase 100 saddles with blankets with my credit card. She bought them at Fort Campbell and from there they were shipped to our position. In less than one week we had the saddles delivered to the ODAs.13

The ground war started on October 19 with the insertion of Special Forces based at K2 into Afghanistan. ODA 555 was inserted into the Panjshir Valley and joined the Jawbreaker team to contact Northern Alliance forces dug in on the Shomali Plains, where they controlled an old Soviet airbase at Bagram. Working closely with Northern Alliance troops under General Fahim Khan and General Bismullah Khan, ODA 555 proceeded to call in air strikes on to Taliban positions along the Shomali Plain.14

ODA 595 was the second TF Dagger team inserted, flying across the Hindu Kush Mountains by SOAR MH-47s. The team was inserted in the Dari-a-Souf Valley, south of Mazar-e-Sharif, linking up with the CIA and General Dostum, commander of the largest and most powerful Northern Alliance faction. Master Sergeant Mike Elmore, part of ODA 595, remembers the insertion:

We got on the birds [helicopters] the night of the 19th. We didn’t know what to expect. We’d heard all the stories about the Northern Alliance, what type of men they were, the continual fighting in Afghanistan for the past 15, 20 years. We had the understanding we were going to link up with a bunch of seasoned fighters.

It was one, two in the morning when we landed and it was pitch black outside. I got off the bird and people were coming out of caves and adobe huts. The first impression I had was, “Where’s Jesus?”

We were carrying 110–115lb rucksacks. The Northern Alliance guys came to help get gear off the helicopter, and watching these guys trying to pick up this stuff was interesting.

Meals were different. For breakfast we had raisins and an assortment of walnuts, peanuts, and cashews. Lunch was an MRE [Meal Ready to Eat] and dinner was usually some kind of goat.

Getting used to the horses and the horses getting use to the ODA team took some adjustments on both of their parts:

I’d maybe ridden horses along little horse trails once or twice before I got there. Might as well call them little ponies. I weigh 220 pounds and with all our equipment you can probably add another 50 pounds to that. The horses were used to a 150lb guy. At one time the horse like, “Hey, forget about it, I’m done, I’m not moving. You’re way too heavy for me, get the heck off.”

ODA 595 split into two units, Alpha and Bravo. Alpha accompanied Dostum on horseback as his force pushed towards the city of Mazar-e Sharif, calling in strikes from US warplanes against a series of Taliban positions. Initially Bravo stayed behind to arrange for logistical support before joining Alpha and General Dostum. Master Sergeant Elmore was part of Bravo, but hadn’t yet come to a mutually agreeable arrangement with his horse.

We were moving into position and I was going from one hill top to another. In between the hill tops is called a saddle, fully exposed because it was a pretty steep drop off. I couldn’t go below to where I wouldn’t skyline myself. The horse just stopped in the saddle. We start taking fire. Bullets are flying all over the place and I’m kicking the horse, hitting, yelling at him. He’s just like: “Hey buddy, I’m not moving.” I’m yelling, screaming, and kicking him. No go, so it was exit stage right, do a roll, and go down a little bit so I wasn’t skylining myself. He’s just standing there, eating grass. No animals were hurt, so I’m sure the animal rights activists will be pleased.

Another Special Forces team, ODA 534, inserted by SOAR helicopters on the night of November 2, was tasked with supporting General Mohammad Atta, a Northern Alliance militia leader. ODA 534, along with CIA officers, eventually linked up with ODA 595 and General Dostum outside Mazar-e Sharif.

This insertion in modified CH-47s was also conducted at night into mountains up to 16,000ft high with clouds, rain, and even sandstorms dramatically limiting visibility.15 Technical Sergeant William Calvin Markham, USAF, 23rd Special Tactics Squadron, inserted with ODA 555 to coordinate close air support (CAS) for the Northern Alliance:

We arrived in country around mid-October and were the only team operating behind enemy lines for the first two weeks. I have worked with SFs in the past and knew several of them from previous scuba training, so we came together quickly as a unit. We knew what our mission was – to help the Northern Alliance break through the Taliban lines and liberate the capital.

We went into the area with just the essential gear, traveling as light as possible. Going as light as possible meant “rucking” up mountains with more than 100 pounds of gear. We had all the communications gear and air traffic control equipment needed to do CAS calls, as well as providing the ground-to-air interface with the aircraft.

We had to contend with the mountainous terrain and the weather elements, as well as the fact that we went in with just enough supplies to last a day and would end up staying nearly ten days. I have done a lot of real-world missions and training exercises in this type of scenario, so I was better prepared for the challenge.

The first day of the operation started what is reported to be the longest sustained close air support operation conducted by combat controllers. “We set up an observation post in a mountain ridge overlooking the Taliban,” said Markham. “The valley was literally filled with enemy tanks, personnel carriers, and military compounds. Working with the Northern Alliance leadership, the target was selected – a command-and-control building. I called in the first CAS and a US military fighter arrived over the area and dropped his ordnance and hit the building.”

That first strike not only made an impression on the Americans, it made an impact on the Northern Alliance forces working with this SOF team.

I wouldn’t say they [the Northern Alliance] mistrusted us initially. But there was a certain sense they weren’t sure how we could help them. After that first CAS run, the wall was broken and they seemed to realize we were there to help them.

With no maps that reflected all the caves, the task would fall to the extensive training we had in land navigation and CAS. The first obstacles were the fact that we didn’t have a detailed map. When you’re talking a pilot on to a target, you have to understand from his perspective that the mountains and desert all looks similar.

The CASs I called in on the site were making an impact, but not sealing the entrances. Many of the caves were lined with concrete and steel. Our team commander told us to figure out how to make the sites inaccessible.

Using a compass, a GPS, notebook, and pen the team set out on the task of creating maps of the caves.

To get exact coordinates and the layout of the cave, we had to create a sketch for each site. It took hours of pacing off the inside and outside of the caves to get good data so we could give exact data to the pilots. We gave each cave a number, then plotted its height on the mountainside, noted any surrounding obstacles, and began pacing off the inside of the tunnels – the slopes, the direction it was dug in, the turns… We tried a few different bombing runs: bringing the bombs in at different angles to get the best possible attack on the sites. After a few runs, we found the best attack was to crack the entranceway and then use a second bomb to collapse the site. The double-bomb drop worked perfectly. The impact was incredible. We had one run that literally blew the cliff line down over the entrance. We secured and destroyed every cave, and ensured they would be inaccessible to anyone ever again.

As the bombings continued, resistance from the Taliban forces decreased and the Northern Alliance gained ground. Then, one day, the enemy counterattacked: “We were on top of a two-story building when they began attacking,” says Markham. “The gunfire was intense. Then, they turned the guns on us. It was like large, flaming footballs flying at our position. The buttons on my uniform were getting in the way of me getting low enough. All I kept thinking was I needed aircraft. I grabbed the radio and called for immediate CAS.”

As the SOF team got on the roof for cover, a Northern Alliance officer pushed in front of Markham, shielding him from the attack. Later, through an interpreter, the officer told him why he had done it: “He said if something happened to him, he knew someone else would step in to take his place in the fight. But if something happened to me the planes could not come and destroy the targets.”16

Navy and Air Force fighters and bombers arrived and blunted the attack, and the offensive continued. A total of 25 days after the first call for ordnance, the Northern Alliance moved into Kabul. After ensuring the city was secure, the SOF team headed to the American embassy, which had been evacuated in 1989. Before fleeing the city, the Taliban had used the building as a staging area. Markham relates: “We gained access and one of the first things I saw was an American flag. It was on top of a pile of straw. Someone had tried to destroy it; the straw was burnt and there were ashes all over the flag. When I picked up the flag, it was untouched – not a burn mark on it. With the help from a teammate I carefully folded the Stars and Stripes. I presented that flag to my unit after I got back to the States.”

Air Force 1st Special Operations Wing (SOW) AC-130H Spectre gunships working out of K2 were part of the CAS assets.17 On one mission Captain Allison Black, USAF, the squadron’s first female navigator on an AC-130H Spectre, earned the nickname “Angel of Death.”

We were in Greece for a while until they sent us to K2. We fly into K2, hit our tents for 12 hours because they figure if we go more than 12 hours we’ll turn into pumpkins. After 12 hours they pull us out of our tents and said “Hey, you’ve got a mission.”

It was a call sign, radio frequency, and a [map] grid or latitude longitude. That was it. We got on the plane, pulled out the chart and figured out how we were going to get there. Our squadron was staying in the northern part of Afghanistan – Mazar-a-Sharif, Kunduz, and north of the [Hindu] Kush.

It was unique from my perspective. Unique but not scary, I was nervous about being one of the only girls out there. I think maybe there was more concern on the guys’ side than there was for me. Don’t care; I wanted to be part of this great mission set.

The customers at the time were primarily ODA teams with our JTACs imbedded, some of which had had worked with me, some who had not.

This first combat mission set we made contact with our ODA team on the ground collocated with the Northern Alliance under General Dostum. He heard me talking on the radio and couldn’t believe it. He said to the ODA leader:

“Americans bring their women here. They must be so determined.”

“Yeah, of course we bring our women to kill Taliban.” was the ODA leader’s reply.

This was my first combat mission and I have to be very professional, bring my A-game. We identified this meeting house and there were multiple vehicles and lots of people which led down the path that we were clear to engage and we unloaded all our ammunition on the target.

At the time the gunship pilots had high power laser pointers, something like you’d use in a classroom. With your NVG [Night Vision Goggles] you can see this. The general saw it and believed it was a Death Ray that we could put on something and it would explode or turn to flames. He turned to the ODA leader and said: “Is that your Death Ray?” believing America had created such a thing. The ODA guys looked at each other and said: “As a matter of fact it is. Yes we have one.”

So General Dostum got on his walkie-talkie and called the enemy we were engaging and said, “You’re pathetic. American women are killing you. It’s the angel of death raining fire upon you.”

As I was communicating to the team what we were doing and what we were seeing he was keying the mike so the enemy could hear the conversation.

Our first mission was very successful. We shot 400 rounds of 40mm and 100 rounds of 105mm. The effects on the battlefield were so impressive that most of the al-Qaeda and Taliban forces surrendered to General Dostum the next day.

So this all goes down and I know nothing about it. We land and about a week later the team comes back to K2 from down range. They come to our hooch with an AK 47 from General Dostum telling us the whole story about how this unfolded and that “You are the Angel of Death, raining death and destruction on our enemies.”18

While TF Dagger was being organized at K2, TF Sword had been embarked on the carrier USS Kitty Hawk (CV(A)-63)19 from Masirah Island off Oman in the Persian Gulf. TF Sword was comprised of an Army SOF command including approximately 600 soldiers and 20 MH-60 Blackhawk and MH-47E Chinook helicopters. For operational security a 5-mile bubble was established around the carrier and her escorts. Kitty Hawk then moved to her station in the northern Arabian Sea to form TG-50.3.

On the night of October 19/20, operating primarily from Kitty Hawk, TF Sword raided the compound of Mullah Omar, a key Taliban leader, near Kandahar, and an airstrip near Bibi Tera, approximately 80 miles southwest of Kandahar. That same night 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, and SOF personnel parachuted on to a landing strip southwest of Kandahar designated Objective Rhino, and Objective Gecko, demonstrating the US’s capability to attack Taliban strongholds.

The plan called for pre-assault fires and then a Ranger airborne insertion on Objective Rhino and a helicopter insertion/assault on Objective Gecko. Objective Rhino, a desert landing strip roughly 100 miles southwest of Kandahar, was divided into four objectives: Tin, Iron, Copper, and Cobalt (a walled compound). Before the Rangers parachuted in, B-2 Stealth bombers dropped 2,000lb bombs on Objective Tin. Then, AC-130 gunships fired on buildings and guard towers within Objective Cobalt, and identified no targets in Objective Iron. The gunships placed heavy fire on Objective Tin, reporting 11 enemy KIAs and nine “squirters” (enemy forces who escaped the initial attack).

After the pre-assault fires, four MC-130s dropped 199 Army Rangers, from 800ft and under zero illumination, onto Objective Rhino. A Company, 3rd Battalion, 75th Rangers, with an attached sniper team, assaulted Objective Tin. They next cleared Objective Iron and established blocking positions to repel counterattacks. C Company assaulted Objective Cobalt, with psychological operations (PSYOPS) loudspeaker teams broadcasting messages encouraging the enemy to surrender. The compound was unoccupied.

An Air Force MC-130 Combat Talon landed 14 minutes after clearing operations began, and six minutes later a flight of 160th SOAR helicopters landed at the Rhino forward arming and refueling point (FARP). Air Force Special Tactics Squadron (STS) personnel also surveyed the desert landing strip, and overhead AC-130s fired upon enemy reinforcements. After more than five hours on the ground, the Rangers boarded MC-130s and departed, leaving behind PSYOP leaflets.

While the Rangers took Objective Rhino, a helicopter-borne assault of Delta Force and Rangers were hitting Objective Gecko. This was a large walled compound belonging to the one-eyed Taliban leader, Mullah Mohammed Omar, situated near the city of Kandahar.

Four MH-47s infiltrated 91 SOF troops into the compound. Security positions were established, and the buildings on the objective were cleared. While the ground forces were clearing the buildings, MH-60s provided CAS, while the MH-47s loitered waiting to pick up the force. It has been reported that as the assault force were preparing for extraction, they were ambushed by a large number of Taliban who were armed with a large supply of rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs). They were extracted from the area under heavy fire. An MH-47 Chinook helicopter was hit, and lost a piece from its landing gear as it took off. At least one soldier was injured during the firefight, reportedly having a foot blown off by an RPG. The ground force spent a total of one hour on the objective.20

While Objectives Rhino and Gecko were being assaulted, four MH-60K Special Operations helicopters inserted 26 Rangers and two Air Force STSs at a desert air strip, to establish a support site for contingency operations. One MH-60K crashed while landing in “brown-out” conditions, killing two Rangers and injuring others.

To the east, Air Force bombings had so severely weakened Taliban defenses around Bagram that they crumbled when General Khan’s forces attacked on November 13. The next day, Northern Alliance forces occupied Kabul without a fight.21

On November 25, 750 Marines of the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit Special Operations Command (MEU SOC) occupied Objective Rhino, which was henceforth known as Camp Rhino. Marines along with an Australian Special Air Service Regiment (SAS) unit began operations against the Taliban to secure Sherzai’s flank as he moved toward Kandahar.22

Major Lou Albano, a Marine CH 53 Chinook pilot, talked about Camp Rhino and the often horrendous flying conditions.

It was desert. They called it a hunting lodge. There were a couple of buildings off to one side and a very austere dirt runway that we weren’t even using to land on, since the dirt was like silt. Every time you’d land you’d kick up so much dust that you couldn’t see anything and you’d just brown out. That was actually the big danger the entire time we were there. On the other side of the runway opposite from where the small set of buildings were we created landing pads.

They were just sandbags that were spray painted and had been set out in a crow’s foot configuration. We’d just land on the sand pads. That’s what it was; it was very austere. We had all our equipment there but there was just one warehouse, three small buildings, a small mosque, and that was it.

We actually ran the gamut [of weather]. It was December when we actually got there and we were there all of December, January, and February. Our detachment was only in Afghanistan for three months. There was freezing rain and that was pretty treacherous and there was a lot of blowing dust which would bring the visibility down, especially at night, to your minimums which was 3 miles visibility. With night vision goggles on that’s treacherous in itself, especially with a low cloud layer. The clouds would come in at night so you’d have maybe 1,000 feet of clearance before you were in the clouds and it snowed a couple of times. It was pretty interesting flying around in the snow. The base altitude even at Camp Rhino was 4,500 feet and at Kandahar it went up to close to 5,000 feet. The service limit of the helicopters is 10,000 feet, so already you’re halfway to the service limit just taking off from the deck. The higher up in altitude you go, the less lift capability you had. It was always a concern. With some of the peaks you had to fly at or a bit above 10,000 feet just to get over them. We didn’t have good maps either. We had these very wide angle maps; the kind of ocean navigation maps. You’d know there was a mountain range but you’d see these gigantic mountains in front of you. You had no idea where you really were on the map and we relied heavily on the GPS. I could pinpoint where I was on the map but what I was seeing in front of me had no relation to where I was on the map. You’d go up and down and over the tops of mountains. It was odd. It was the most unique kind of navigation and the terrain was pretty treacherous.23

Operational tempo for aircraft flying CAS was intense. Captain Black, 1st Special Operations Wing, recounts what it was like.

We were flying almost every day. Occasionally fly three days and get a day off. We flew always at night. We’re fat, heavy, and predictable. We flew low enough to get good fidelity on our sensors which doesn’t work in the daylight particularly when you’re shooting at people and they want to shoot back. We very concerned about the moonlight, flying only after EENT [end evening nautical twilight, i.e. nautical dusk] and before BMNT [begin morning nautical twilight, i.e. nautical dawn]. We lost airplanes and crew members because they were exposed in the daylight.

We were at Mazar-e Sharif, Kunduz, working with different ADO teams. It was fairly easy because all the lights were out and the towns were dark. If the lights were on it got your attention. If people were out during the times we were flying 95 precent of the time they were up to no good. All the folks who didn’t want to get into trouble were home tucked away quietly so it was easy to spot activity. When we engaged the enemy it was apparent they didn’t know what we were. How they were trying to be deceptive wasn’t working. They expected ground artillery fire, but it was coming from the air. It took a few weeks and then we saw their body language change. They would stay still when we engaged. They would hide more effectively.

The US efforts in the fighting up north suffered a setback on December 5. While the Special Forces were calling in CAS, a 2,000lb joint direct attack munitions (JDAM) bomb landed in the middle of their position. The soldiers were literally blown off their feet. Three Americans were killed and dozens wounded, along with many of their Afghan allies.24 Major Richard Obert, USAF, remembers this well.

We were launched to go land in a flat spot in the desert and do a CASVAC because an ODA team had dropped a JDAM on themselves. There was a bunch of dead Afghanis, a couple of dead Americans and a bunch of really hurt guys that needed treatment immediately. They were pulled out on helicopters and again this was early on where Bagram and Kandahar weren’t secured.

We landed in a flat spot in the desert, transloaded off the helos to us and then flew them to Oman where there was a better level of care; I guess that is how I should say it. Me and the loadmasters were cutting up everything we had in the back of the airplane to make bandages … there were some guys that were bad off. There were also guys that had been living there on the compound, or the hangar, with us, for a week or two before we went in and computer emergency response team (CERT’d) them; we knew some of them. I don’t want to say that that made me feel good because I didn’t like seeing it; I didn’t like having the guy that didn’t have an eye anymore ask me for my magazine and give me a thumbs up when I gave him my magazine because he’s the least hurt guy in the back of the airplane.

I wasn’t that young, like 24, but that’s a different feeling when you see a guy like that when you were throwing a football around with him the week before…

The doctor actually gave us the feedback that in his opinion getting them to that care that quickly – it was about a three hour flight to Oman from where we were – saved a couple of the guys’ lives.

The treatment from the flight doctor that we had with us, the loadmasters, and I had provided in the back significantly reduced some of the trauma in terms of blood loss. We had water and other stuff like that to help with the shock because some of the guys had shrapnel wounds and that water had really helped them a lot in terms of treating them once they got there. That’s a feeling of knowing that those guys were really having a bad day and we were able to help them out.”25

Following the loss of Kabul and Kandahar, Taliban and al Qaeda forces retreated south to two refuges. One was in the Shah-i-Kot Valley in Paktia province and the other was the Tora Bora Valley located in the Spin Ghar (White Mountain) region of Nangarhar province. The valley is six miles wide, 6¼ miles long, and surrounded by 12,000–15,000ft mountains that form a concave bowl facing northeast. The primary avenue of approach into the area is from the town of Pachir Agam south through the Milawa Valleys that joins the Tora Bora Valley at its eastern end. The valley is only 12 miles from the Pakistan border. Most of the al Qaeda positions were spread along the northern wall of the valley.

The CIA-led Jawbreaker Team Juliet, supervised by Gary Bernsten, arrived on a ridge overlooking the Milawa Valley north of Tora Bora in late November and saw hundreds of al Qaeda combatants, command posts, vehicles, and other facilities spread out in the valley below.26 There were strong intelligence indications that bin Laden and other senior al Qaeda leaders were in the complex when the fighting began on December 5.

Assault forces included ODA 572, under the command of Master Sergeant Jefferson Davis, and coalition ground and air forces aircraft, in addition to a collection of local militias totaling approximately 2,500 fighters grouped under the label “Eastern Alliance” (EA). The alliance was comprised of four anti-Taliban groups led by commanders Hajji Qadir, Hajji Zahi, Mohammed Zaman Ghun Shareef, and Hazrat Ali. Unlike the Northern Alliance forces, these militias were mutually hostile groups – so hostile in fact that at times they fired at each other.

Special Forces teams set up observation posts along the east and west ridgelines of the complexes and began calling in air strikes. The battles took place during the Muslim holiday of Ramadan, during which no food or water is to be consumed from dawn to dusk. Each day, fighting began at first light and continued into the night, when the EA forces would withdraw from the valley to their camps while the enemy remained in the valley. When enemy forces lit campfires at night, SF teams used thermal-imaging scopes to call in attacks by bomb-equipped aircraft and gunfire missions by AC-130 Spectre gunships.

Captain Black was on one the gunships flying CAS at Tora Bora.

At Tora Bora we were looking for the cave complexes. At the time we didn’t have the fidelity to show the elaborate caves they ended up having. We looked for anything man-made – trails, any 90-degree angles, anything that stood and shouldn’t be up on 14,000ft mountains. We found and engaged entryways and could see the effects from the top of the ridgeline. If we were shooting from the side of the ridgeline we could see smoke from the top. We didn’t know what it was at first. It was coming from the air ducts. Probably the most dangerous part of our mission set was when we flew close to the mountains. They could get up close and personal. If they had the weaponry they could get a good shot at us.

The EA forces’ withdrawal each night meant that much of the same ground would have to be taken again the next day. Air strikes coordinated by Jawbreaker and SF teams continued almost continuously for 72 hours. On December 9, TF 11 arrived and took control of the operation. Task Force 11 consisted of 50 US Army Delta Force troops from A Squadron, Navy DEVGRU, Air Force STS, along with 12 British Special Boat Service (SBS) commandos, and one British Royal Signals Specialist from 63 Signals Squadron. German KSK Kommando Spezialkräfte (Special Forces Command, KSK) forces moved in to help protect the flanks and run reconnaissance missions.

The battle went on and included 17 more hours of continuous air strikes between December 10 and 11. Finally, on December 17, most of the remaining al Qaeda and Taliban fighters slipped away, their retreat covered by al Qaeda’s most fanatical fighters lodged in caves. At the time, CENTCOM did not have forces trained or equipped to operate in the severe Spin Ghar winter conditions or the air assets needed to block the routes into Pakistan.

In the aftermath of the battle the cave complex was carefully examined. Instead of a massive fortress complex, only a natural cave system to which minor improvements had been made was found. No evidence was discovered that any major leaders of al Qaeda or the Taliban had been killed, although there was proof that bin Laden had been there when the fight began.

Kandahar, the last Taliban-controlled city, fell without significant fighting on December 7. The Taliban movement had started in Kandahar, and the city was considered the true capital of Afghanistan by the largely Pashtun population. No one expected an easy fight. While Sherzai positioned his forces to attack the airport, Karzai was negotiating for the Taliban to surrender. On December 7, Sherzai began his assault on the airfield. His forces moved carefully to the entrance, but unexpectedly found no resistance. In the midst of the operation he received a phone call informing him that the Taliban had completely evacuated Kandahar as a result of Karzai’s negotiations.

Two days earlier, members of the UN Afghanistan Committee had met in Bonn, Germany, to sign the “Agreement on Provisional Arrangements in Afghanistan Pending the Re-establishment of Permanent Government Institutions.” The agreement contained the terms to transfer power to an interim Afghan administration effective from December 22, 2001. Hamid Karzai was selected as chairman of the administration.

The agreement also established the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), a NATO-led security mission whose main purpose was to train the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) and assist Afghanistan in rebuilding key government institutions, in addition to fighting insurgent groups.27 ISAF, led by a two-star general (COMISAF), was headquartered in Kabul. ISAF’s area of responsibility at this time only covered Kabul and the immediate surrounding area. The British Major General John McColl was ISAF’s first commander.

As the fighting rapidly progressed across Afghanistan, General Franks and Secretary Rumsfeld discussed post-combat troop strength. Not wanting to repeat the Soviet mistake of flooding the country with tens of thousands of foreign soldiers, General Franks recommended that the total be kept to approximately 10,000 Army, Air Force, Marine, and Special Forces personnel, with enough assets for air assault operations as needed. The 10,000 included three brigades of the 10th Mountain and the 101st Airborne (Air Assault) Divisions and the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit (and attached units). These forces were placed under the newly formed Combined Forces Land Component Command (CFLCC) Forward. CFLCC was responsible for controlling conventional operations, coordinating with Special Operations Forces, and providing logistical support in the Afghan theater. Major General Franklin Hagenbeck, 10th Mountain Division commanding general, was placed in charge of CFLCC.

On December 12, Major General Hagenbeck and his division headquarters staff arrived at K2 to set up shop. The staff of the headquarters totaled slightly more than 150 soldiers to handle forces more than six times its size.

In Afghanistan, the Army 1st Battalion, 87th Infantry, 10th Mountain Division, and Air Force units established a primary operating base at the old Bagram Soviet air base, while the Marines moved from Camp Rhino to Kandahar Airport. They were replaced there by the 3rd Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division.

By the end of 2001, organized al Qaeda and Taliban resistance ended and a new government was in power. Since Afghanistan no longer had an army tracking down and eliminating remaining Taliban and al Qaeda fighters, this was left to coalition forces. The 10th Mountain and 101st Airborne units swept the countryside looking for weapons caches and any remaining enemy fighters.28

At this time there were two distinct military commands operating in Afghanistan, with different focuses. The first was Operation Enduring Freedom, the American-led coalition operating throughout the country and focused on eliminating the Taliban and al Qaeda threat. The second, mentioned above, was the UN-sanctioned ISAF based in Kabul. ISAF was tasked with the security and stability of Kabul, not the broader national threats and regional instability. Thus, combat operations, nation building, stability operations, and humanitarian efforts were directed by the US and (primarily NATO) coalition forces in the majority of the country.

In previous wars Afghanistan combat operations had been curtailed during the winter months due to the severity of the weather. Snow closed mountain passes to traffic and made flying a nightmare when pilots were caught in whiteouts. Extreme cold affected not only men, but also made metal brittle and froze oil in motors. Most enemy fighters went to ground, fading into villages or crossing into sanctuaries in Pakistan. But there would be no break this winter. As the new year dawned, coalition forces were to pursue al Qaeda and Taliban fighters through some of the bitterest weather and on some of the highest peaks in the world.