The majority of the insurgency now centered on three distinct but overlapping geographic fronts: northern, central, and southern. The northern front encompassed Pakistan’s North West Frontier province and northern parts of the FATA, to such Afghan provinces as Nuristan, Kunar, and Nangarhar. Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e-Islami was the predominant militant group in the area. In addition, criminal organizations were also very active and not reluctant to engage in combat operations to protect their smuggling operations.

The central front was further south along the border from Pakistan’s FATA to eastern Afghan provinces including Paktika, Khost, and Lowgar. Sirajuddin Haqqani’s network had reported links to Pakistan’s Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence, from which it received aid, and had become lethal at conducting attacks deep into Afghanistan. Another group on this front was Hezb-e-Islami Khalis, which was led by Anwar ul Haq Mujahid. Al Qaeda was also active in the region.

Mullah Omar’s Taliban based in the vicinity of Quetta, Pakistan, operated in the southern front, including Kandahar and Helmand provinces. Working with the Taliban were criminal groups, primarily drug traffickers who ran operations on both sides of the Afghanistan–Pakistan border and ran criminal networks through Iran and Central Asia.

Although not a threat to US, NATO, or coalition forces, Abdul Rashid Dostum and Atta Mohammad established strong power bases and controlled significant resources and militia forces in the north. These forces weakened the central government’s power and drew off money and assets needed in other areas for stability operations.1 With increasing numbers and groups of hostile forces, 2009 was shaping up to be a bloody year.

On January 1, Taliban insurgents attacked a US base in Helmand province, losing three men and failing to breach the base defenses. In Shah Wali Khot district of Kandahar province Canadian troops killed the driver of an explosive-laden vehicle before he could reach his target. Afghan troops in Herat province weren’t so fortune, losing one man to a suicide bomber.2

There was no lull in the fighting. Although not leading any major, named operations through the late winter and into spring, US forces supported NATO forces throughout Afghanistan. All of the operations included ANSF.

On January 7, US and ANSF forces moved into the Alishang district in the northeastern province of Laghman to disrupt the Taliban’s IED construction. “During the operation, as many as 75 armed militants exited their compounds and attempted to converge on the force,” the US military statement said. “Shooting from rooftops and alleyways, the militants engaged coalition forces with small-arms fire in the village.”

In the resulting firefight 32 insurgents were killed, one suspected militant was detained, and two large caches of weapons and explosives were destroyed.3 Another six militants were killed in an operation involving Afghan soldiers and US-led forces in Farah province.

The same day, the British-led Operation Shahi Tandar (aka Operation Atal) moved into the Khakrez and Shah Wali Khot districts of Kandahar in RC-South. Focusing on destroying IED production capability, the operation involved the British 42 Commando Royal Marines, 24 Commando Engineers Regiment, Canadian 3rd Battalion, Royal 22e Régiment, 2-2 US Infantry, units of the Royal Danish Army, and ANA troops, all of which extensively combed the areas.4

According to Lieutenant Colonel Roger Barrett, Commanding Officer of the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment Battle Group: “The purpose of the operation was to disrupt terrorists in the Western Panjwayi and Western Zhari districts, and specifically target areas where the enemies of Afghanistan make and store explosive materials, weapons, and equipment.”

When the operation was over on January 31, the forces had seized six large caches of explosives, 38 pressure plates used to detonate hidden mines, 3,000 rounds of ammunition, AK-47s, anti-personnel mines, 22 RPGs, and 20kg of opium. They had captured eight Taliban bomb-makers, and killed several senior Taliban commanders. One key success was the destruction of a facility used to produce vehicles packed with explosives (Vehicle Borne Improvised Explosive Devices – VBIEDs).

Starting in April, RC-North and RC-West were the focus of Taliban campaigns after having been comparatively quiet since 2002. The attacks threatened key supply routes coming out of Uzbekistan, and regional stability for the upcoming Afghan presidential election in August 2009.

Living conditions for US troops in RC-East stationed at remote combat outposts and isolated observation posts were austere.

Major Dave Lamborn, a company commander for 4th Brigade, 101st Airborne, discovered this when he took over as company commander. “They weren’t getting mail. They were running out of food and water out in the mountains. Of course, they’re getting attacked, that’s natural. That’s par for the course, but it’s the other things. They did not feel like they were being supported by anybody, by battalion or by brigade. They had very little contact with family members back in the States – like I said, they weren’t getting their mail. When they stopped getting routine shipments of food and water, they really felt like they had been left out there to their own devises. So, morale was really bad.”5

Major Casey Crowley, Headquarters Troop (HHT) commander for 3/61 CAV [the reconnaissance squadron for 4th Infantry Brigade Combat Team (IBCT) from 4th Infantry Division (ID)] talked about the situation when the unit arrived in RC-East:

The brigade was going to deploy to what was called Nangarhar province, Nuristan province, Kunar province, and Laghman province in Afghanistan; the brigade footprint was called N2KL. Those are the two Ns, the K, and the L. The brigade headquarters was in Jalalabad and sort of encompasses the Torkham Gate area. That was more in the southern part and we were north of that. For the most part the N2KL is a very, very austere and mountainous region.

I’m never one to complain [about] the living conditions themselves on the FOB. We had hot and cold running water; we had air conditioning and heat. We had electricity and everything else. Once you got to the mountaintops where the guys were it was a lot more austere and some of these locations are accessible only by helicopters. There was one road that came down from Jalalabad and went a little further from our FOB but not much further. Most of the hilltops we had guys on were helicopter only. We didn’t have too many Pathfinder or air-assault-qualified people but when we did resupply those were the ones who had to rig sling loads for the helicopters to get them food, water, and ammunition.

Whether it was the winter (it was harder to fly in the winter) or the summer (they couldn’t carry as much in the summer because it was too hot), the weather would come in, aircraft would break, or sometimes the pilots wouldn’t want to fly to a location because they thought it was too dangerous. It was prioritizing what those guys got and unfortunately that’s always going to be food, fuel, and ammunition. Mail and ice cream didn’t always get out to them, which is tough for the guys. That was probably the most difficult challenge we had to deal with.6

The 4th IBCT was also tasked with interdicting smuggling along the border with Pakistan, as Major Crowley recalls.

As battle space owners we would meet with our local political counterparts – the police chief, mayor, and that sort of thing – as well as partner with the security forces, and not just the Afghan National Army but also the Afghan Border Police because we were so close to the border with Pakistan.

The police chief in our area was probably one of the most outspoken Afghans I’ve met. As the police chief he wanted to do tactical missions and go after bad guys. We were like, “No, no. Unfortunately you’re not in the Army. You’re here to just secure the populace in your district.” We had to try and tone him down but he had a really good police force. [In] the ABP corruption is sort of an inherent part of their culture and way of life. The ABP were by far the most corrupt of the organizations. They would take a lot of bribes on the border to let stuff come in and go out or whatever. That was very frustrating. Their battalion commander was a very interesting dude who was Mujahedeen and he was probably the single most responsible person. Although he could have easily doubled for Jerry Garcia – same beard and glasses and everything – I think the Taliban gets to these guys in the leadership positions and puts pressure on them. They threaten their families. We could sort of see that his hands were tied on the ABP side.

We would see timber smugglers with donkeys loaded with timber coming from Pakistan. Ideally we wanted to see insurgents coming across the border. I think the timber was going into Pakistan and the insurgents were coming in to Afghanistan.

Up in the town of Nuray there was a lumber pile that was probably 3km by 3km. I’m not saying tree trunks; these things were blocks 3ft by 3ft by 30ft. These things were huge and they just stay there; they couldn’t do anything with it. That was one of the things we asked them about: “This is just sitting here. You guys can sell it.” “No, the Taliban owns this. We can’t touch it.” The lumber just sat there. It was one of the very interesting political dynamics we were in.7

Smuggling wood was a small part of the pandemic lawlessness plaguing the government in the eastern provinces; the major part remained the growing amount of drug trafficking in the southern provinces. It was estimated by United Nations officials that in 2008 the export value of opium poppy crop and its derived opiates reached over $3 billion. Money from the drug trade financed the Taliban, al Qaeda, and other anti-government groups. It also added to the corruption of appointed and elected Afghan officials.8 In October 2008, President Karzai replaced Interior Minister Zarrar Moqbel (a Tajik) with Muhammad Hanif Atmar (a Pashtun) and tasked Minister Atmar with working to combat corruption in the police forces and ministries.

The key to reducing the trafficking was poppy eradication. To accomplish this, in early 2009 the ANSF fielded Counter Narcotics Infantry Kandaks (CNIK) and ANP units in Helmand province. Each unit had a US Army or Marine Embedded Training Team (ETT) to assist. This was part of a wider program of shifting the responsibility for conducting operations away from coalition forces and onto ANSF. At the time, the Ministries of the Interior and Defense supervised the following counter-narcotics law enforcement and military units: Counternarcotics Police-Afghanistan (CNP-A); National Interdiction Unit (NIU); Sensitive Investigations Unit/Technical Intercept Unit (TIU); Central Eradication Planning Cell (CPEC); Poppy Eradication Force (PEF); CNIK; Afghan Special Narcotics Force (ASNF); and ABP.9

“Whether it’s man, train and equip ANSF units … whether it’s ANSF casualties or troop movements; that all falls into our visibility,” said Captain Charles Hayter, the Marine Expeditionary Brigade-Afghanistan ANSF future operations coordinator. “We provide the expertise on ANSF activities.”

Not surprisingly, Taliban and criminal networks fought to stop the CNIK. One of the CNIK ETTs was from the Illinois Army National Guard. The following are excerpts from reports written by Major Kurt C. Merseal, team chief, covering the unit’s operations from February 1 through March 26 in the vicinity of Nad Ali. The reports show how dangerous it was for both Afghans and Americans.10

The ANA’s CNIK was tasked with conducting a joint operation with the ANP’s Poppy Eradication Force (ANP PEF) and DynCorp (a US contracting firm) in an area north of Nad Ali city.

As the unit moved into position it began taking small-arms and machine-gun fire, along with indirect mortar and RPG fire. One ANA soldier was wounded. Soon afterward another ANA soldier was hit.

The team’s medic, Specialist Rowton, then ran to the scene to assess the wounds and provided combat care under fire until the wounded soldier could be transported out of the immediate area. The 3rd Advising Team then attempted to secure transportation for the wounded man through an ANA soldier nearby, but he would not leave his covered position, as he was taking heavy machine-gun fire. Private Garcia, without regard for his own safety, and on his own initiative to secure the life of the soldier, ran to the truck while heavy machine-gun fire was landing near him and over the team’s head, and moved a vehicle to their position to provide cover and then transport. Both ANA casualties were safely evacuated, but the unit didn’t make it to the poppy fields.

The situation got worse on February 16. At 4:11pm, Major Merseal reported that the CNIK and CNIK ETT began receiving direct small-arms fire from southeast of their positions. On or about 12:38pm Major Merseal then reported that an RPG 7 warhead had been thrown through the window of one of 1st Companies’ Ford Rangers and was lodged against the back seat. The warhead had been fired in the vicinity of the 1st and 3rd ANA CNIK companies and their respective advising teams.

DynCorp’s Explosive Ordinance Detachment (EOD) was requested, as the warhead was still intact. EOD arrived on the scene, removed the warhead, and detonated it at 1:28pm.

While this was going on 1st and 3rd companies began receiving small-arms and machine-gun fire. Dismounts from the companies and their respective advising teams began to conduct fire and maneuver onto several clots in response to the S3’s order. 2nd Platoon, 1st Company was directed to push forward in order to assault enemy forces located to their south. The first house was cleared with little resistance. However, the platoon began to receive fire from a house to the east. Two platoons from the 2nd Company were ordered to move forward to support the 1st Company. These platoons failed to move forward, as the company’s Executive Officer reportedly turned his radio off.

As the dismounted ANA force cleared the first clot, enemy fire began from another, and several fighters ran from one clot to another to the east. As two ANA soldiers approached the entrances to two separate clots, they came under machine-gun fire. One soldier was hit in the head and the other was hit in the torso. At this time, the 1st and 3rd Advising Teams were moving forward to the position. Lieutenant Mays pushed forward with his team and determined that the reported wounded ANA soldier was actually KIA. He then moved forward of their position in response to orders, but without regard for his own safety, to throw a fragmentary grenade into the house from which the team was receiving heavy machine-gun fire. Approximately 15 minutes later, Captain McLean (a US Army nurse) arrived to assess the second soldier, and determined that he was KIA. At 1:29pm Major Merseal reported to the Joint Forward CP that two ANA soldiers had been killed in the contact, as their injuries were too extensive for treatment.

The enemy force stayed and continued to fight on in the face of significant firepower by the CNIK, CNIK ETT, and attack-helicopter support (two Hellfire missiles were fired, in addition to 30mm cannon rounds).

This day’s operations resulted in two KIAs within the CNIK, five confirmed enemy KIAs (believed to be as high as 12), and with 14 detainees being taken. On February 21 the opposition used a ZSU-23 (a two-barrel 23mm antiaircraft gun) and 107mm rockets to stop the CNIK. And so it continued. Each day the units encountered increasing resistance while only occasionally managing to destroy some of the surrounding poppy fields. At the time of Major Merseal’s last report on March 26, the opposition fielded enough fighters to lay siege to ANA patrol bases and sustain attacks over extended periods of time. Poppy production continued, despite the costly efforts in men and equipment by the CNIK, ANP, and their US-led ETTs.

In February and March 2009, President Obama approved an increase of over 17,000 US forces to deploy during the course of the year. By June there were approximately 55,000 US troops in Afghanistan. Some 8,000 came from the 2nd Marine Division and another 4,000 from the 5th Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division, which was the first time the Army had deployed this type of brigade to Afghanistan. The remaining 5,000 were support forces including military police and engineers drawn from regular, reserve, and National Guard units.

The additional US forces deployed in RC-South to stop the influx of foreign fighters coming over the border from Pakistan through an increased number of “seize and hold” operations spread over more territory, helped provide stability, and trained ANSF.11 Operations included establishing bases, which would provide greater mobility and counterinsurgency efforts.

The Marines were first to strike into enemy territory. On July 2, 4,000 2nd Expeditionary Brigade Marines and 650 ANA troops struck over a 75-mile front into the Helmand River Valley south of Lashkar Gah. Operation Khanjar (“Strike of the Sword”) was the largest Marine operation since the Vietnam War.

Key targets of the assault included the districts of Garmsir and Nawa near the southern border with Pakistan. One of the immediate goals was to secure the area before the presidential elections. This time, instead of a quick in-and-out, the forces were to remain in place, working with Afghan farmers to develop alternate crops to replace opium poppies. More than 90 percent of Afghanistan’s poppy production comes from Helmand province, making the area a major cash supplier for the Taliban. The Marines anticipated a hard fight based on an Afghan Army Intelligence estimate that there were 500 foreign and 1,000 Afghan Taliban fighters in the area.

“This is a big, risky plan,” Marine Brigadier General Larry Nicholson told his men at a briefing at Camp Leatherneck in the run up to the launch of the battle. “It involves great risks and amazing opportunities. These are days of immense change for Helmand province. We’re going down there, and we’re going to stay – that’s what is different this time.”

The Marines did not employ artillery or bombs from aircraft, in an effort to show that the operation focused more on protecting people than on killing the enemy. “The success of this operation is going to be dependent on how the populace views this, not just in how we deal with the enemy,” Captain Pelletier said.

The operation launched at 1:00am local time, July 2, 2009, when Marines from 1st Battalion, 5th Marines (1/5), were dropped by CH-47 and UH-60 helicopters of the 82nd Airborne Division into dirt fields around the town of Nawa-l-Barakzayi, south of Lashkar Gah. Two Marine infantry battalions and one Marine Light Armored Reconnaissance (LAR) battalion led the operation.

In the north, 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines (2/8) pushed into Garmsir district. In central Helmand, 2nd Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion (2nd LAR) entered Khan Shin in the Khan Neshin district, at the same time as 1-5 Marines pushed into Nawa-l-Barakzayi.

The first shots of the operation were fired at daybreak (around 6:15am) when a Marine unit received small-arms fire from a tree line. Cobra attack helicopters were called in and made strafing runs at the tree line from where the fire was coming from. Simultaneously, Marines from 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines (2/8) were dropped by helicopters just outside the town of Sorkh-Duz. This lies between Nawa-l-Barakzayi and Garmsir (where the unit had fought in 2008). Conditions in the field were hot and dry, with temperatures reaching over 100°F (38°C). Heat stroke was as much a risk for the heavily laden troops as was enemy fire and IEDs.

“We were kind of forging new ground here, going to a place nobody has been before,” said Captain Drew Schoenmaker, who commanded Bravo Company of 1st Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment.

The next three hours brought repeated bursts of gunfire and volleys of RPGs. A Cobra helicopter providing CAS fired rockets at a tree line nearby. Other Marines walked through fields of corn and hay. Only a handful of villagers dared to venture outside into the area of crisscrossing canals, mud houses, and lush tree-lined fields.

“It’s like when you open up the oven when you’re cooking a pizza and you want to see if it’s done, you get that blast of hot air. That’s how it feels the whole time,” said Lance Corporal Charlie Duggan Jr.

By July 3, Marine Colonel Mike Killion reported: “An enemy-controlled baseline just south of Garmsir was crushed yesterday, but that doesn’t mean all the enemy have gone.” This was proven the next day when Taliban militants shot and damaged two unarmed medical helicopters marked with a red cross, deployed to evacuate Marines suffering from heat stroke.

The stiffest resistance occurred in the district of Garmsir, where Taliban fighters holed up in a walled housing compound engaged in an eight-hour gun battle with troops from 2nd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment. The Marines eventually requested a Harrier fighter jet to drop a 500lb bomb on the compound. There was no immediate count of insurgents killed, although ground commanders reported that 30–40 were shooting from in and around the compound early in the day. The airstrike also resulted in several secondary explosions, leading Marines at the site to suspect that the house may have contained homemade bombs.

Poppy eradication was not part of the Marines’ mission. Brigadier General Nicholson addressed this in his press conference:

Coalition forces, and particularly US Marines, were not involved in eradication. Eradication is a program that is run by the Afghan Government. So now, if they are somewhere out eradicating and they’re in a firefight, will we come to their rescue? Absolutely. Will we MEDEVAC them? Yes, we will. But are we out there? You will never see Marines out there plowing fields, digging – you know, I mean, it’s just – that’s not why we’re here. That’s not what we’re doing. That’s an Afghan program. And so I hope that answers that.

Now, if I find – if our Marines are out there and they find a lab, if they find a drug lab, will they report it to the Afghan officials? Will they cordon off the area and treat it like a crime scene and bring in Afghan Government folks? Absolutely. But are we out there hunting labs? Are the Marines hunting labs or hunting poppy fields? The answer is unequivocally no.

Officially the operation ended on August 20, however, Marines set up several operating and logistics bases throughout the region. For all the combat, only one Marine was killed and several others were injured or wounded on the first full day of the assault. Also on the first day, Lieutenant Colonel Rupert Thorneloe (one of the most senior British Army officers in Afghanistan) and another British soldier were killed when a bomb exploded under their armored vehicle near Lashkar Gah. The ANA lost two men and one interpreter. For all the effort, the confirmed number of Taliban killed was between 49 and 62.12

Post-operation intelligence indicated the Taliban escaped the area prior to the start of the operation, rather than choosing to fight. The fighters had moved to German-controlled northern Helmand near Baghran and the eastern edge of Farah province, an area mostly under Italy’s control. General Zahir Azami, the Afghan Ministry of Defense spokesman said: “They want to carry on fighting. They don’t want to escape during the summer. This is the height of fighting season.”

A senior coalition officer who agreed to speak only if he was not identified said: “The sense is that many of the Taliban have left, but they have not gone very far. They are not abandoning the Helmand River valley. They have seen a lot of forces come and go, but we are not going anywhere.”13

Although Operation Khanjar was considered successful, work still needed to be accomplished. Several follow-on clearing operations ensued in some areas to clear out Taliban militants and give Afghan civilians the security and freedom of movement required to participate in the August 20 national and provincial elections.

One of these operations took place on July 18 when Marines with Company F, 2nd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment (2/8) and ANA soldiers conducted an early-morning raid on a prominent Taliban-controlled bazaar near Mian Poshteh. “The purpose of the raid was to disrupt freedom of movement within the bazaar and to exploit the enemy force logistic base,” said Captain Junwei Sun, commander of Company F. “This seizure means we invaded Taliban territory, discovered their caches, disrupted their log operations, and squeezed them out of the area.” Just over two months later, 2/8 Marines established a patrol base within close proximity to this bazaar in order to deny the insurgents influence in the area for the long term.

After studying insurgent movements and activities in the Now Zad region, approximately 400 Marines of 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment (2/3) along with 100 ANA and British troops supported by Marine Aircraft Group 40 launched Operation Eastern Resolve II against the town of Dahaneh, a Taliban stronghold for the past four years. The operation began on August 12. Control of the town was essential to controlling the Now Zad Valley, a major Taliban staging area and large opium market, as well as the best vehicle route connecting Taliban safe havens in northern Helmand. Later that morning a convoy of Marines met heavy resistance as they fought to seize control of the mountains surrounding Dahaneh.

It took three days of heavy fighting to secure the town at a cost of one Marine killed, Lance Corporal Joshua “Bernie” Bernard. Although the Taliban were defeated, the villagers weren’t convinced they would not come back. Marine Captian Zachary Martin, operation commander, gave a realistic assessment of the situation: “They’re waiting to see what we’re going to do. They want to see if we’re going to stay the course, if we’re going to be the winning side, because they very much want to be on the winning side.”14

During the operation, which commenced just a few weeks before the national and provincial elections, the Marines established a position between the insurgents and the village of Dahanna. Another achievement in the operation was establishing a presence in the Dahanna Pass, which served as a logistical resupply route for the insurgency. The Marines’ intense efforts provided the security required to allow people to vote in the August 20 elections.

Other significant accomplishments for 2/3 include the compacting of Route 515, which was initially cleared by 3/8 to connect the districts of Deleram and Bakwa. After the route was cleared, it continued to be plagued with IEDs. Today, the road is still dangerous, but much safer due to the project 2/3 facilitated.15

The loss of a friend is hard, as is the loss of a man under your command. Army Major Louis Gianoulakis tells what it was like.

I served at Contingency Outpost [COP] Michigan. It’s a COP in the Dari-Pesh district in Kunar province within RC-East. It’s at the mouth of the Korengal Valley and the Pesh River, which snaked through my area of operations [AO]. On the west side Sundri was the border and on the east side Metina and Cara were the borders. I lost three Soldiers from my company; two while I was in command and one a month after I left command.

Making that phone call to speak to the mother of the first Soldier was probably one of the most difficult things I’d ever done in my whole life. I’d been a casualty assistance officer before, I’ve been an escort officer before to bring a Soldier home, but making that phone call and talking to the Soldier’s mother [was hard]. It turned out to be a wonderful experience and we had a great conversation, but just the initial opening of the conversation, talking to her – even though I knew she’d been notified, even though I knew she’d spoken to other people – just to be the guy who was responsible for her son. It was hard to talk to her.

The first Soldier [who died] was a very vibrant and energetic Soldier who could turn a very drab, boring day into a very exciting event. He just had that personality. He died doing exactly what you would want a Soldier to be doing: trying to get his weapon back into operation so he could continue to lay suppressive fire for his element – he was a Mk-19 gunner – so they could call for some indirect fire and hopefully kill the enemy, but at a minimum suppress the enemy and get them out of the kill zone without anybody getting injured. His Mk-19 [grenade launcher] malfunctioned; he switched to his 240Bravo [machine gun] and then deemed it would be more effective if he got back on the Mk-19, and that’s when he took a round to his head.

Dealing with the casualties was by far the hardest thing I had to do, and it’s something you cannot make a mistake with anywhere in the process. There are no-fail missions at the tactical and operational level, but I would say it is more important to ensure that that Soldier and his family are taken care of the right way, because without those Soldiers you’ll never accomplish any other mission. If you fail to do that, your men will see it.16

The men and women who lost their lives were flown home out of Bagram Airfield. A ramp ceremony was held for each one as their coffin was loaded on board the aircraft. People stood at attention, holding a salute until the last coffin passed.

Major Melvin Porter, 3-61 Cavalry company commander, and his unit had just arrived. He relates: “After we got off the plane, they told us to drop our bags and run back to the ramp, so my guys had just hit the ground and now they have to do a ramp ceremony where they drive the [HMMWVs] with the coffins of three soldiers past them. That was really sobering for them, too, especially for some of the younger guys, who had never deployed at all. As soon as they hit the ground the first thing they see are three American bodies.”

It didn’t get easier for him or his troops when they flew into their COP in RC-East.

It took us maybe two to three days to get from Bagram to our actual COP. Then we were on the ground for a couple of hours and we get into our first firefight. We landed on the COP probably about 0230 to 0300, and about 0700 there was an enemy attack. The COP sat in a depressed low area with high ground all around it, so it was interesting to get there and know that you were going to be fighting from a bowl for a year. That was a daunting task to look at going ahead. One of the Soldiers for the unit that we were replacing was injured pretty badly, so it was really an eye-opening experience for my Soldiers, and even prior to that, as soon as we landed in Afghanistan at Bagram, there had been an attack and some Soldiers had been killed.

While the major fighting was taking place in RC-South, two small operations were run in RC-East to enhance security for the presidential elections. The 2nd Battalion, 377th Parachute Field Artillery Regiment, 4th Brigade Combat Team (Airborne), 25th Infantry Division, along with ISAF and ANA forces, ran the week-long Operation Champion Sword at the end of July against insurgent safe havens in the Sabari and Tirazayi districts of Khost province. The operation netted 14 militants captured with no casualties.

In the first week of August Operation Silver Creek was kicked off with the same mission of enhancing security before the elections in Nuristan province on August 20. The 2nd Battalion, 77th Field Artillery Regiment, 4th Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division and ANA forces with the Marine Embedded Training Team 4-4 from the 3rd Marine Division were the units assigned to this operation.

Back on June 15, General Stanley L. McChrystal relieved General David D. McKiernan as ISAF Commander and Commander of US Forces − Afghanistan. It was the routine annual change and, at the time, did not alter operational planning. The first indication of General McChrystal’s views on how the war should be fought was stated in “Commander’s Initial Assessment” submitted to Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates on August 30.17 In the opening paragraph General McChrystal wrote: “Stability in Afghanistan is an imperative; if the Afghan government falls to the Taliban – or has insufficient capability to counter transnational terrorists – Afghanistan could again become a base for terrorism, with obvious implications for regional stability.”

He then redefined the fight as one not “focused on seizing territory or destroying insurgent forces” but rather stated the need to conduct “classic counterinsurgency operations in an environment that is uniquely complex.” Success, he contended, “demands a comprehensive counterinsurgency campaign.” Accomplishing the mission required a “change in operational culture” and a new strategy focused on the population. There was also the acknowledgement that time was critical. After almost eight years of war McChrystal believed that “failure to gain the initiative and reverse insurgent momentum in the near-term (next 12 months) – while Afghan security capacity matures – risks an outcome where defeating the insurgency is no longer possible.”

One of the strongest points in the summary was the need for more troops. In public statements he suggested an additional 30,000–40,000 US forces were needed in addition to the 65,000 already in country.

The offensive went on. In RC-East Operation Buri Booza II on September 8 had ANA and ABP forces moving into Ganjgal village in Kunar province. With the ANA was the Marine ETT 2-8 (Major Kevin Williams, Lieutenant Ademola D. Fabayo, 1st Lieutenant Michael Johnson, Gunnery Sergeant Edwin Johnson, First Sergeant Christopher Garza, Staff Sergeant Aaron Kenefick, Corporal Dakota Meyer, and Navy Hospital Corpsman 3rd Class James Layton). Captain William D. Swenson and Sergeant 1st Class Kenneth Westbrook from the 10th Mountain Division were with the ABP.18

This was supposed to be a routine operation similar to ones the units had run before. “We were not there to fight, we were there to have the Afghan forces prove to an unreceptive audience that the government was fair, professional, responsible, and most importantly, it was Afghan,” said Captain Swenson.

Intelligence sources hadn’t reported any heavy concentration of anti-government forces in the area. “The valley is notorious for welcoming you in, and your farewell present is always fire – always,” Swenson said.

But this time an RPG hit the front of the column as the lead Marines moved within 100m of the village. Then the entire force was hit by heavy machine-gun fire, RPGs, and AK-47s from the valley to the east. “We’re surrounded!” Gunnery Sergeant Edwin Johnson yelled into his radio. “They’re moving in on us!”

An estimated 60 insurgents had infiltrated and maneuvered into Ganjgal from the north and south through unseen trenches. Heavy fire spewed from houses and buildings. According to eyewitnesses, village women and children could be seen shuttling ammunition and supplies to the Taliban fighters.

In the first attack, Johnson, Kenefick, Johnson, Layton, and an Afghan soldier they were training were killed.

At least twice, a two-man team attempted to rescue their buddies, using an armored vehicle mounted with a .50-cal machine gun to fight their way toward them. They were forced back each time by a hail of bullets, RPGs, and mortars. A bullet hit the vehicle’s gun turret, piercing Meyer’s elbow with shrapnel. Eventually, Meyer reached the trapped men. He found them spread out in the ditch, dead and bloody from gunshot wounds. Their weapons and radios had been stolen.

“I checked them all for a pulse. Their bodies were already stiff. I found Staff Sergeant Kenefick face down in the trench. His face appeared as if he was screaming. He had been shot in the head.”

Bleeding from his shrapnel wound and still under fire, he carried their bodies back to a Humvee with the help of Afghan troops and escorted them to the nearby Forward Operating Base Joyce, about a mile to the northeast of Ganjgal.

Coalition forces had been flanked and were taking rocket and artillery fire on three sides from multiple angles and elevations by the advancing Taliban. “The enemy realized they were gaining the initiative and that our fires were ineffective,” Swenson said. “We called in artillery, but we couldn’t put it where we wanted to, and they saw that as a deficiency on our part and exploited it. This was a maneuvering enemy, a thinking enemy, an aggressive enemy, and a new enemy.”

Swenson called repeatedly for white phosphorous smoke to shield the coalition and allow them to withdraw. He was repeatedly denied the incendiary rounds on the basis that the drop would be too close to a populated civilian area. The closest obscuring effect of the White Phosphorous shells shells was 400m away, too far away to be effective as cover for the withdrawal.

“A difficult decision was reached that we were no longer combat effective. We were going to be overrun, so we started a controlled withdrawal, but it was not the decision we wanted to make because we still knew we had the Marines up ahead,” Swenson said. “We didn’t know where and were hoping, just hoping they’d taken cover inside a building and stayed there, thus the break in communication. We just didn’t know, but what we did know was that we’d be no good to them where we were, so we began our withdrawal, with additional casualties.”

Major Williams had been shot in the arm and Garza’s eardrums had been ruptured by an RPG. The wounded were accumulating. Unable to physically evacuate the wounded down the steep terraces and out of the kill zone, Swenson coordinated for combat helicopter support.

Westbrook had been isolated and lay in the open suffering a chest wound.19 Negotiating 50m of open space, Swenson, Garza, and Fabayo quickly covered ground, zig-zagging and returning fire as they raced for Westbrook. Despite the maelstrom of direct fire, which had killed two ANA soldiers and wounded three others, the team was holding their own in the kill zone.

At about the same time, a team of OH-58D Kiowa Scout helicopters carrying a combination of missiles, rockets, and .50-cal machine guns arrived on the scene.

“We did receive our aviation support, the Kiowas,” Swenson recalled. “They’re aggressive, like little bees, they swarm all over the place, quick, nimble. The enemy knows when helicopters show up it’s in their best interests to find somewhere to hide. If the enemy is out in the open, they’ll be found and that will be a bad day for them.”

Swenson and Fabayo then manned one of the unarmored ABP trucks and re-entered the kill zone twice to evacuate wounded and bringing them to a casualty collection point. Next, Swenson and Fabayo went in search of the missing Marines, while staying in constant contact with one of the helicopters, which was also trying to locate them.

The arrival of the Kiowas gave them the time needed to move Westbrook and the other wounded down the steep terraces to the ABP trucks, which then carried the wounded to a landing zone where a UH-60 Blackhawk MEDEVAC helicopter waited.

A mission that started as one of good will became a struggle for survival. The immediate cost to the coalition was the loss of four Americans and eight ANA soldiers. Approximately 12 insurgents were killed.

Captain Swenson summed up the operation in just a few words. “There was loss, terrible loss, but we brought forces in to continue that mission, to finish that mission, to clear that village, and to show what our resolve was and what our response would be.”20

The next major insurgent (referred to as Anti-Afghan Forces, or AAF) attack in RC-East took place against COP Keating near Kamdesh, Nuristan province. The attack was the result of the decision by General McChrystal to withdraw troops from remote outposts and consolidate them around larger population centers. COP Keating, along with several other tiny firebases in eastern Afghanistan, was ordered to shut down. The COP lay in a deep bowl surrounded by high ground, with limited overwatch protection from nearby OP Fritsche.

The COP and OP were manned by 60 men from Bravo Troop, 3rd Squadron, 61st Cavalry Regiment, 4th BCT, 4th Infantry Division, along with two Latvian Army advisors to the ANA forces. During the five months of B Troop’s deployment to COP Keating, the enemy launched approximately 47 attacks – three times the rate of attacks experienced by their predecessors. Usually the attacks were made by just a few fighters, and lasted five to ten minutes. This changed on the morning of October 3.

At approximately 5:58am, both the OP and COP were hit with concentrated fire from B10 recoilless rifles, RPGs, DShK heavy machine-gun fire, mortars, and small-arms fire from the heights. This immediately inflicted casualties on the COP’s guard force and suppressed COP Keating’s primary means of fire support, its 60mm and 120mm mortars. ANA soldiers on the eastern side of the compound failed to hold their position, and within 48 minutes enemy fighters penetrated the perimeter at three locations. Once inside the wire, the attackers burned down most of the barracks and managed to wound 22 soldiers and kill eight, in total half of the approximately 60 Americans there.

Insurgents also captured the outpost’s ammunition depot. Eight Afghan soldiers were wounded, along with two Afghan private security guards. Some of the defenders took refuge in armored vehicles, but at least two were killed by shrapnel from RPGs that breached their turrets.

Lieutenant Cason Shrode, fire support officer, said the initial round “didn’t seem like anything out of the ordinary.” There was a lull and then there was a heavy attack. “We started receiving a heavy volley of fire. Probably 90 seconds into the fight they ended up hitting one of our generators so we lost all power. At that point I knew that this was something bigger than normal.”

When the attack started, Staff Sergeant Clinton L. Romesha, a section leader for Bravo Troop, pushed through heavy enemy fire to the Long Range Advanced Scout Surveillance vehicle battle position 1, or LRAS 1, to ensure that the MK-19 automatic grenade launcher and Specialist Zachary S. Koppes were in the proper sector of fire and engaging enemy targets. He then headed to the barracks, grabbed an MK-48 machine gun, and, with assistant gunner Specialist Justin J. Gregory, moved through an open and uncovered avenue that was suppressed with a barrage of RPGs and small-arms fire. Romesha grabbed a limited amount of cover behind a generator and destroyed a machine-gun team that was on the high ground to the west. He then engaged and destroyed a second enemy machine gun.

Continuing to fight under the heavy enemy indirect and direct fire from superior tactical positions, and suffering a loss of power to the tactical operations center (TOC) when enemy forces destroyed the main power generator, B Troop withdrew to a tight internal perimeter. Within 40 minutes, A-10s, F-15s, a B-1 bomber, and Apaches arrived on the scene. Chad Bardwell, an Apache gunner, said he had to confirm the fighters he saw on ridgelines were the enemy because he had never seen such a large group of insurgents. “We tried to stop them as they were coming down the hill… We were taking fire pretty much the entire day.” One of the pilots’ initial reports described, in laconic terms, flying through gauntlets of fire, and occasionally finding a shooting gallery of insurgent targets.

Chief Warrant Officer Ross Lewallen, the Apache pilot, said a few aircraft were damaged in what was a “time-consuming endeavor” governed by tough terrain. “One of the primary reasons for the fight taking so long is that it is an extreme terrain. There’s a lot of cover so you really can’t detect the enemy until they start moving again,” he said, adding that it was tough for MEDEVAC aircraft to land “because we were still trying to control [the outpost].”

As CAS was raking enemy positions, Romesha engaged multiple enemy positions on the north face, including a machine-gun nest and sniper position. With 3rd Platoon providing a base of fire to cover the assault on the entry control point building, Romesha led a team to secure and reinforce it using an M-203 grenade launcher and a squad automatic weapon (SAW). Once in the building he ascertained that the source of the enemy recoilless rifle fire and RPGs was originating from the village of Urmul and the ANP checkpoint directly to the front of the entry control point. He then called in CAS and heavy mortar fire to take care of the problem; air support neutralized AAF positions in the local ANP station and mosque in the nearby village of Urmol, as well as in the surrounding hills.

The fighting died down at 5:10pm when the last of the AAF withdrew. The Quick Reaction Force was delayed by bad weather and didn’t reach the COP until 7:00pm.

During the attack eight US soldiers were killed and 27 wounded; eight Afghan soldiers were wounded, along with two Afghan private security guards.21 The US military estimated that 150 Taliban militants were also killed as a result of repulsing the assault. One of the defenders, Staff Sergeant Clinton L. Romesha, was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions during the attack.22, 23

In the days following, B Troop withdrew from COP Keating, but, the Americans left so quickly that they did not carry out all of their stored ammunition. The outpost’s depot was promptly looted by the insurgents.

In RC-South, Marines continued operations to clear the Taliban out of the region. From October 6–10, 200 Marines from 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment along with the Afghan 2nd Battalion, 2nd Brigade, 207th Corps conducted Operation Germinate to clear Taliban insurgents out of a pass through the Buji Bhast Mountains in Farah province. Company F traveled into the dangerous pass to clear the route connecting the population centers of Golestan and Delaram in order to allow freedom of movement for local Afghans in the area. Along the route through the pass, Taliban-planted IEDs had killed more civilians than Marines.

“I figured it was either going to be a ghost town or it was going to be a significant battle,” said Captain Francisco X. Zavala, Company F’s commanding officer. “Unfortunately, there was some battle, but it was nothing my Marines couldn’t handle.” As the ground element rolled through the pass, the rest of the Marines and ANA soldiers who had been inserted via helicopter blocked the eastern and northern exit routes. Their supporting mission was to stop and search Afghans fleeing the area and prevent any possible insurgent support from reinforcing their comrades.

“We saw spotters throughout the hills, and we were just waiting for something to happen,” said Staff Sergeant Luke N. Medlin, the engineer platoon sergeant and part of the eastern blocking position.

A few hours after they assumed these blocking positions, the Marines and Afghan soldiers started receiving fire from machine guns, rifles, and mortars from enemy positions in the surrounding hills. The Marines quickly dispatched the initial attackers and called in a UH-1N Huey, an AH-1W Super Cobra, and an F/A-18 Hornet to destroy the enemy position farther uphill. “We were attacked from a well-fortified fighting position in the hills,” Medlin said. “My Marines quickly returned fire, giving us time to maneuver and overwhelm the position with fire until air support got there.”

The only other excitement during the operation came two days later. “During the clearing of one compound, a woman drew a pistol, aiming it at one of the Marines,” said Lieutenant Shane Harden, weapons platoon commander, F Company. “Lance Corporal Justin B. Basham demonstrated extreme composure and great fire discipline not to shoot her. Within a split second he realized that he could use a non-lethal method to disarm her.”24

Marines and sailors from India Company, 3rd Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment returned to towns surrounding the Buji Bhast Pass area as part of Operation North Star from November 15–17. They found the Taliban reasserting its influence by shooting at the Marines. The patrol attended a shura in the town of Gund, and the Taliban responded to the meeting with small-arms fire from the surrounding hills.

“[The Taliban] responding to the shura in that manner. [By] shooting at us, they’re just trying to reinforce their presence there to the locals. They wanted to let [the locals] know, ‘Hey, we’re still here, we see you talking to the coalition forces, and we don’t like it,’” said 1st Lieutenant Scott Riley.

Taliban fighters increased their efforts to reinforce their influence over the region later in the day. This third attempt targeted the Marines, using an IED. “We turned around to look at how beautiful the valley was up there with all the mountains, when we saw a huge plume of smoke and dirt shoot up. Then we waited and eventually heard the explosion,” said 2nd Lieutenant Robert Fafinski, a platoon commander with India Company. “We were pretty sure somebody had died, and eventually we were able to learn from the locals that it was the IED emplacers.”25

Although no villagers or Marines were hurt during the operation, it was obvious that efforts to eliminate the Taliban’s influence had not yet been successful.

Operation Cobra’s Anger targeting the Nawzad District in the volatile Helmand province was more rewarding. The three-day operation ran from December 4–7, where members of 3rd Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment returned to the town of Now Zad. Alpha Company, 2nd Combat Engineer Battalion traveled by road while other units air assaulted using via CH-53E helicopters and V-22 Osprey aircraft. After clearing multiple IEDs the Marines entered the town and came under fire.

“An insurgent shot at us and we saw him peeking from behind a corner shooting rounds at us,” said Corporal Trevor W. Curtis, a vehicle gunner for Lima Company. “Once we had him spotted, one of our gunners shot at him with a .50-cal machine gun and I unloaded my Mark-19 on him. After we shot, a tank fired at his building and all that was left was rubble.”

“I thought they’d put up more of a fight,” said Corporal Cody P. McGuire, a combat engineer for Alpha Company, 2nd Combat Engineer Battalion. “This was a hot spot, but there was very little resistance, except for IEDs. I was there three days and found three IEDs. They have the capability to put up a good fight. But we rolled in with assault breacher vehicles, tanks, and air support. I think they were intimidated.”

After the operation ended, Navy medical personnel assigned to the Marines treated about 300 people while Lieutenant Colonel Patrick J. Cashman, the Marine CO, and Lieutenant Colonel Sakhra, commander of the ANA 207th, met with tribal elders to build rapport with the locals scattered along the route to the pass and the ANA forces in the area.

“As far as bringing the people back into the city, we are about 50 percent, because we have to de-mine the place and clean it up,” said 1st Lieutenant Mathew M. Digiambattista, 1st Platoon commander, Alpha Company, 2nd Combat Engineer Battalion. “Given the right tools and time, we can accomplish anything.”26

This post-operation work was part of the overall COIN strategy and, for the immediate future, helped keep the area secure.

In 2009 the US lost 310 people, of which 266 were killed in action. General McChrystal’s new policies were being implemented, but it was too early to assess their long-term impact. What was evident was that the Taliban and other anti-government forces had not been brought under control or even seriously weakened in RC-South, even with the heavy concentration of US, ISAF, and ANA forces. In RC-East ISAF and US forces ceded control of the more remote areas in an effort to concentrate forces around population centers. The Haqqani Network and Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin continued to be the dominant forces in the region, and there was no apparent way to interdict their operations. Germany had command of RC-North. Over the year, German forces, working with Swedish, Norwegian, US, ANA, and local security forces, conducted a series of operations resulting in the death of over 600 insurgents. But the areas outside of the vicinity of major bases remained under the control of the Taliban and its allies. RC-West remained as it had been – dominated by anti-government forces and criminal organizations.

After eight years of war, the end was not yet in sight.

Darunta guerrilla training camps. Satellite imagery from clearly shows cave entrances and training camps. The digital imaging sensor is designed to produce images with superior contrast, spectral resolution, and accuracy. (Space Imaging)

The Twin Towers of the World Trade Center smoking on 9/11. The al Qaeda sponsored assault on targets in the United States was the instigator of the US attacks on Afghanistan in Operation Enduring Freedom. (Michael Foran)

A view of the damage done to the Western Ring of the Pentagon after American Airlines Flight 77 was piloted by terrorists into the building on 9/11. (US Navy)

Donald H. Rumsfeld (left), US Secretary of Defense, greets Hamid Karzai (right), chairman of the Afghan Interim Administration, at the Pentagon on January 28, 2002. (DOD, photo by Robert D. Ward)

A Tomahawk cruise missile is launched from USS Philippine Sea in a strike against al Qaeda terrorist training camps and military installations of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan on October 7, 2001. The carefully targeted actions were designed to disrupt the use of Afghanistan as a base for terrorist operations and to attack the military capability of the Taliban regime. (DOD photo by Master Chief Petty Officer T. Cosgrove)

ODA operators meet with General Tommy Franks in October 2001. Note the pakol hats, Mk 11 sniper rifle (left), and M4A1 carbine fitted with a sound suppressor and the ACOG 4x optical sight. (USSOCOM/DOD)

An iconic image of Special Forces in Afghanistan. From the Harley Davidson merchandize Realtree hunting jacket, and Confederate flag, it is safe to assume a southern ODA. (Courtesy “JZW” c/o Leigh Neville)

US Army Special Forces troops ride horseback alongside Afghan Northern Alliance horse cavalry on December 11, 2001. The deployment of these SF teams was a key element in the early success of Enduring Freedom, as they coordinated massive air attacks on Taliban and al Qaeda positions. (US Army)

Women in burkas in Mazar-e-Sharif on December 15, 2001. Mazar-e Sharif was the first major center to fall to the Northern Alliance forces of General Dostum, backed by US Special Forces. (USAF)

Local Afghanis ride a taxi at the Mazar-e-Sharif airfield during Operation Enduring Freedom, December 15, 2001. (USAF)

A lead element of more than 45 Jordanian Special Forces soldiers stationed outside of Aman, Jordan, arrived in Mazar-e Sharif, Afghanistan, in support of Operation Enduring Freedom, December 24, 2001. (USAF)

Northern Alliance troops under General Dostum’s command in Mazar-e-Sharif take a break on a wall in the median of the town’s busiest street. (USAF, photo by Staff Sergeant Cecilio Ricardo)

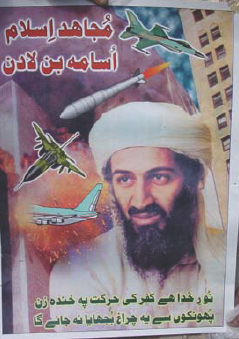

During a search and destroy mission in the Zhawar Kili area on January 14, 2002, US Navy SEALs found valuable intelligence information, including this Osama bin Laden propaganda poster. In addition to detaining several suspected al Qaeda and Taliban members, SEALs also found a large cache of munitions. (US Navy)

A poster depicting General Ahmed Shah Massoud overlooks the Olympic Stadium in Kabul during a football match between a local team, Kabul United, and ISAF, February 15, 2002. It was the first international sporting event to take place in Afghanistan in five years. (Imperial War Museum, LAND-02-012-0293)

March 2002: the rugged summit of Takur Ghar, with the snow-covered floor of the Shah-i-Kot Valley beyond. It is possible to make out, on the streak of snow at 4 o’clock from the single cross-shaped tree on the center skyline, “Razor 01,” the abandoned MH-47E Chinook of the Ranger QRF. (USSOCOM/DOD)

Soldiers from Bravo Company, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) prepare to move out after having been dropped by a Chinook helicopters during Operation Anaconda on March 5, 2002. (US Army, photo by Sergeant Keith D. McGrew)

A Marine AH-1W Cobra takes off from USS Bonhomme Richard in support of Operation Anaconda on March 4. At times the number of CAS assets over Takur Ghar created severe command-and-control difficulties. (USMC)

An aerial view of a rugged mountain pass near Gardez. The mountainous terrain provided many hiding places for groups like al Qaeda and the Taliban. (US Army)

Members of the 2nd Battalion, 187th Infantry conduct a dismounted sweep and clear during Operation Mountain Lion, a follow-up operation to Anaconda in April 2002. This clearly shows the type of terrain Coalition forces were forced tonavigate. (US Army)

Two MH-47E Chinooks of the 160th SOAR launching on a mission somewhere in Afghanistan. (DOD)

A member of the Afghanistan Military Forces has a cigarette while on guard. The AMF were responsible for keeping the locals away while coalition forces, headed by the US Army Criminal Investigation Division (CID), unearth graves in the village of Markhanai on May 5, 2002 in Tora Bora, for Operation Torii. (USAF)

US Army soldiers assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division prepare to enter and clear a room while searching for weapons in Paktika province during Operation Mountain Sweep on August 21, 2002. They are armed with 5.56mm M4 carbines and an M136 light anti-armor weapon (US Army).

A UH-60Q Blackhawk from the 717th Medical Company flies through the scenic mountains of the Gardez Pass returning from FOB Salerno after an equipment change over on January 25, 2004. (US Army)

This view from the crew door of a UH-60Q Blackhawk, from the 717th Medical Company (Air Ambulance), shows the rough terrain of northeastern Afghanistan on the route back from FOB Salerno on January 25, 2004. (US Army)

US Marines patrol through a dry creek bed while they search caves in Khost on August 18, 2004. The Marines were conducting vehicle checkpoints and village assessments while maintaining an offensive presence throughout the region in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. (DOD, photo by Lance Corporal Justin M. Mason)

A US Army soldier provides security as a gun team moves down a mountain after making contact with the enemy near Ganjgal on October 16, 2004. (DOD, photo by Specialist Harold Fields)

US Marines conduct a mounted patrol in the cold and snowy weather of the Khost–Gardiz Pass in Afghanistan on December 30, 2004. The mountainous region, not far from the Pakistan border, would be a constant thorn in the side of Coalition forces. (DOD, photo by Corporal James L. Yarboro)

A soldier from the 29th Infantry Division of the Virginia National Guard stoops to enter and search the home of a suspected Taliban member in Afghanistan on June 4, 2005. (DOD, photo by Staff Sergeant Joseph P. Collins Jr.)

An AC-130U gunship from the 4th Special Operations Squadron jettisons flares. The flares are a countermeasure for heat seeking missiles that may be aimed at the planes real-world missions. (USAF)

RQ-1 Predator UAVs, like this one, have been used to increase battlefield awareness at operating locations in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. Intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets, including UAVs, have flown more than 325 missions to provide battlefield awareness in support of Enduring Freedom. (USAF)

The HH-60 Pave Hawk is the Air Force’s primary search and rescue helicopter. It has an 8,000lb capacity two cargo hook pylons for mounting crew-served 7.62 or .50 caliber machine guns for protection. Operationally, Pave Hawks work in pairs for mutual fire support and suppression in kinetic situations. (DVIDS photo)

The AH-64D Apache Longbow attack helicopter’s weapons package includes a 30mm automatic Boeing M230 chain gun located under the fuselage with a rate of fire of 625 rounds a minute. It also has four hardpoints mounted on stub-wing pylons, typically carrying a mixture of AGM-114 Hellfire missiles and Hydra 70 rocket pods. (DVIDS photo)

A US Air Force F-15E Strike Eagle aircraft flies over Afghanistan in support of Operation Mountain Lion on April 12, 2006. US Air Force F-15, A-10 Thunderbolt II, and B-52 Stratofortress aircraft provided CAS to troops on the ground engaged in rooting out insurgent sanctuaries and support networks. (DOD, photo by Master Sergeant Lance Cheung)

A US Army M-ATV leads a resupply convoy during Operation Helmand Spider in Helmand province. The device attached to the grille of the vehicle is a counter-Ied device, designed to jam the signal sent to any remotely controlled electronic IED. (US Army)

The High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle (HMMWV) is a lightweight, highly mobile, diesel-powered, four-wheel-drive tactical vehicle that uses a common chassis to carry a wide variety of military hardware ranging from machine guns to tube-launched, optically tracked, wire command-guided (TOW) antitank missile launchers. (Military.com)

Snipers of the French 2nd Foreign Infantry Regiment using a PGM Hécate and a FR-F2 in Afghanistan in 2005. French troops were part of the ISAF contingent that expanded considerably after 2006. (Davric)

A US Army staff sergeant looks over a cliff as he provides security while his fellow soldiers, Afghan National Army soldiers, and US Air Force airmen of the 755th Explosive Ordnance Disposal Unit move to an enemy weapons cache point on the side of a mountain on December 23, 2006. (DOD, photo by Staff Sergeant Marcus J. Quarterman)

A British Army convoy makes a temporary halt in opium poppy fields outside the town of Gereshk in Helmand, 2006. The opium poppy is traditionally the main cash crop of Afghanistan. Until the late 1990s, Afghanistan was the world’s leading supplier of opium. Whilst in government, the Taliban outlawed opium cultivation, nearly eliminating it from the country entirely by 2001. However, production revived quickly after American forces overthrew the Taliban government. (IWM, 12BDE-2007-010-343)

Paratroopers from the 782nd Brigade Support Battalion, 4th Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Division watch as combat delivery system bundles carrying food and water come floating to the ground in the Paktika province of Afghanistan on October 11, 2007. (DOD, photo by Specialist Micah E. Clare)

A 120mm mortar is fired in support of combat operations in the Da’udzay Valley in the Zabul province of Afghanistan on October 23, 2007. This operation was a joint Afghan National Army and ISAF mission to clear anti-government elements from the Dawzi area. (DOD, photo by Sergeant 1st Class Jim Downen)

Paratroopers from B Company, 1st Battalion, 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division patrol the Ghorak Valley in Helmand during Operation Achilles, March 6, 2007. (Public Domain)

A Marine Special Operations Company’s leatherneck examines a poppy plant handed to him by an Afghan National Army soldier (right) during a patrol on February 25, 2008 through a village in Helmand where they were looking for Taliban fighters. (DOD, photo by Staff Sergeant Luis P. Valdespino Jr.)

An F/A-18C Hornet aircraft from Strike Fighter Squadron 113 refuels from a US Air Force KC-10 Stratotanker aircraft over southeast Afghanistan during a mission supporting international security forces in Helmand on October 6, 2008. The squadron was embarked aboard the aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan to provide support to ground forces in Afghanistan. (DOD, photo by Commander Erik Etz)

A Fairchild Republic A-10A Thunderbolt II, known as the Warthog from its less than pleasing aesthetics, sits on the strip at Bagram Air Base. The Warthog was introduced late into the battle and flew top cover for the extraction helicopters. (DOD)

Members of ODA 3336, 3rd Special Forces Group (Airborne) recon the remote Shok Valley of Afghanistan where they fought an almost seven-hour battle with insurgents in a remote mountainside village as part of Operation Commando Wrath. (US Army)

A US Army sniper teams provides overwatch while an officer surveys a village during a foot patrol near FOB Mizan on February 23, 2009. (DOD, photo by Sergeant Christopher S. Barnhart)

US Marines and Afghan National Police officers conduct a security patrol through the Nawa district of Helmand province, August 3, 2009. The severity of the insurgency in Helmand meant that the British troops who had been based there since 2006 were heavily reinforced by US Marines and other troops in 2009. (DOD, photo by Corporal Artur Shvartsberg)

A US Navy Petty Officer treats a Marine who was wounded during a firefight in the Nawa district of Helmand, August 14, 2009. Navy corpsmen are first responders to wounded Marines on the battlefield. (DOD, photo by Corporal Artur Shvartsberg)

A US Marine with 2nd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment reaches for more rounds during an attack at Patrol Base Bracha in the Garmsir district of Helmand, on October 9, 2009. The Marines are deployed with RCT 3, whose mission is to conduct counterinsurgency operations in partnership with Afghan security forces in southern Afghanistan. (DOD, photo by Sergeant Pete Thibodeau)

US Air Force F-15E Strike Eagle aircraft from the 335th Fighter Squadron drop 2,000lb joint direct attack munitions on a cave in eastern Afghanistan on November 26, 2009. (DOD, photo by Staff Sergeant Michael B. Keller)

US Marines board a V-22 Osprey aircraft at Control Base Karma in Helmand on June 9, 2010. (DOD, photo by Corporal Lindsay L. Sayres)

A group of houses surrounded by mountains sit over a rocky foundation across the river in the Dara District of Panjshir. (US Army, photo by Sergeant Teddy Wade)

US soldiers patrol in Baghlan province in January 2011. The district saw a surge of Taliban attacks in the months around this image. (Corbis)

US Marines with Lima Company, 3rd Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment patrol through Bar Now Zad, January 13, 2010. The Marines are moving into the area to deny the Taliban freedom of movement. (USMC, photo by Corporal Daniel M. Moman)

US Air Force Captain Nick Morgans, a pararescueman with 46th Expeditionary Rescue Squadron, scans his sector on the way to a landing zone during a mission near Kandahar on December 24, 2010. A pararescueman’s primary function is as a personnel recovery specialist with emergency medical capabilities. (DOD, photo by Staff Sergeant Eric Harris)

Members of the US Army’s 502nd Regiment fire a mortar during 2010’s Operation Hamkari in Kandahar. This image is part of a winning portfolio for the army photographic competition in 2011 (© MOD, Crown Copyright, photograph by Sergeant Rupert Frere)

US Army Private 1st Class Ben Bradley, left, a Bulldog Troop, Red Platoon scout from 7th Squadron, 10th Cavalry Regiment, ducks away from small-arms fire as fellow scout, Sergeant Jeff Sheppard, launches a grenade at the enemy’s position during a combat engagement in northern Bala Murghab Valley, part of Operation Red Sand, April 4, 2011. (Strategypage.com, photo by Technical Sergeant Kevin Wallace)

US Defense Secretary Panetta visits troops at FOB Shukvani, March 14, 2012. Following the massacre of 16 Afghan civilians by an American soldier, Panetta told troops that it should not deter them from their mission to secure the country ahead of their withdrawal. (Corbis)

This Buffalo MRV, equipped with the anti-RPG “slat” armor, survived an IED attack that took the two front wheels off its axle. The crew survived. (US Army)

As the US prepares to withdraw forces from Afghanistan, combat operations turn to training of Afghan troops. Here Afghan National Army soldiers train on a Humvee in Nuristan. (Corbis)

President Obama and Afghan President Karzai hold a meeting at the White House, January 11, 2013, discussing the continued transition from US-led operations and the partnership between the two nations. (Corbis)

As part of the effort towards withdrawal, US forces, as part of the Coalition, train Afghan security. Here a police officer graduates in Herat, December 2013. (Corbis)