The training for an MWD never ends.

Ever.

Even at night and in all kinds of weather and environments: in water, the pitch black of night, jumping out of helicopters.

“Just like Marines, if we don’t continue the dogs’ training, it can easily diminish and they will forget things,” said Cpl. Sean McKenzie, a handler based at the Marine Corps base in Okinawa, Japan. “It’s important to keep on training because in the event that a team is needed immediately, the dogs can do what they are tasked to do.”

“We’re constantly training, constantly improving,” said Tech. Sgt. Chad Eagan, a handler based at Cannon Air Force Base in New Mexico. “Detection is the main reason our dogs are here, so that’s what we focus on.”

Training never stops for the dogs, even when they are deployed; in fact, if anything, it ratchets up whenever an MWD team is sent to a new area with unknown and strange smells, people, and terrain. It also serves to strengthen an already tight bond between dog and human.

“Deployments are probably one of the most bonding experiences an MWD team can have,” said S.Sgt. Jessie Johnson, a handler with the 56th Security Forces Squadron at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona. “There wasn’t more than two hours a day when I wasn’t with my dog. I needed him to protect myself and the team, and he needed me to take care of his daily needs.”

“You get attached to different units, so a lot of the time your dog is your only friend,” said S.Sgt. Daniel Andrzejewski, kennel master at Marine Corps Base Camp Butler in Okinawa, Japan. “You eat together. You sleep together. You play together. Wherever you go, the dog goes.”

When deployed, MWD teams frequently have to improvise, assembling rudimentary obstacle courses from whatever materials they can find, but once they’re back at their home base they train at a dedicated well-equipped facility. However, if the chance comes to train in a real-world building or environment like a football stadium or a school, handlers and trainers usually grab it.

“We pretty much stay on the installations, but now we are starting to build up a better point-of-contact training schedule so that we can leave installations and come out to areas like this,” said Sgt. 1st Class Raymond Richardson, kennel master at Joint Base Myer–Henderson Hall in Landover, Maryland, referring to a recent MWD training exercise at FedExField. “The stadium itself is insanely large, and challenges the handlers as well, not only the dogs. [Commercial] kitchens are also great, because they smell like food and grease, which are good distractions for the dogs.”

“The training should be a fun experience for the dogs,” said S.Sgt. Charles Hardesty, kennel master at the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center in Twentynine Palms, California. “If the dog thinks training is going to get him in trouble, it is not going to do its job.”

The constant training and ongoing vigilance don’t just benefit the dogs, but the handlers as well. “The dogs teach you something every day,” said Air Force S.Sgt. Jessie Johnson, a handler based at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona. “There is never a time you can say you’ve taught a dog everything or that a handler knows everything. I learn every day. I’ve never been so happy to want to go to work.”

Just as many two-legged soldiers may be called to respond quickly in any possible kind of environment—from blazing-hot deserts to a subzero Arctic blizzard—the same goes for canine soldiers. Even though water training is not a standard part of most MWD training regimens, many bases do occasionally provide the opportunity to their MWD teams.

“[Most] dogs have been trained for a desert environment,” said Cpl. Jonathan Scudder, a handler at the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center in Twentynine Palms, California. “Exposing them to water prepares them for where they may go when they change stations or handlers.”

He added that while some dogs take to the training like, well, a duck to water, some are more reluctant. “How quickly a dog gets accustomed to training in and around water depends on each individual dog and the handler’s training,” Scudder noted. “We take baby steps to ease them into the idea of swimming and practicing what they know while in water. It’s best described as success of approximation.”

Cpl. Paul Kelley, a handler also based at Twentynine Palms, believes it’s imperative that every canine soldier acquire some practice doing his job in a water environment. “If a working dog gets deployed with a handler to a combat zone and the Marine has to swim a distance with his rifle and combat load, he has to have confidence that his dog will be able to follow him effectively,” Kelley said. “We have to prepare them for where they may go. As handlers we have to make sure we keep training to build that confidence with them.”

Just as there are many people who are not crazy about flying, the same applies to dogs, including those who serve in the military.

But because canine soldiers are so often called upon to travel to far corners of the world, it’s a necessary evil. However, there’s a big difference between traveling in a cargo plane and jumping out of a helicopter and / or shimmying down a rope while a chopper hovers noisily overhead. That’s why many military bases have ramped up training in recent years.

Handler Sgt. Nina Alero, for one, would have welcomed the training since she and Rex, her canine partner, already had to board a helicopter with no previous training. “Rex was stressed out because of all the noise, it was like sensory overload for him,” Alero said. “This training would have been beneficial to have prior, so I could have known my dog’s reaction to getting in and out of the chopper.”

Previous training would have benefited those military personnel who rescue others as well. “Most pararescuemen have never hoisted dogs into a helicopter before, so this [training session] was an experiment to see how the dogs would react to the sound of the helicopters and being in air,” said S.Sgt. Kenneth O’Brien, a pararescueman with the 83rd Expeditionary Rescue Squadron based at Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan.

One way to meet the need for such high-wire training is to practice by rappelling, which is referred to in the military as fast-roping. Camp Hansen in Okinawa, Japan, has a dedicated rope tower where Marines can practice with and without their dogs.

“The [fast-roping] … was a lot different because you had a dog on your back, and he is moving around,” said Lance Cpl. David Hernandez, a handler with the 3rd Marine Expeditionary Force at the camp. “This is an experience most dog handlers do not get to have.”

Cpl. Nicholas Mejerus, another handler at Camp Hansen, agrees. “If we were to get attached to a unit that is trying to do an air assault, and that handler dog team had never done that kind of training before, they wouldn’t know what to do,” he said, adding that with the experience under their belt, they can help guide others, through either a simulated exercise or the real thing. “Now that we have done it, we can share our knowledge with other Marines.”

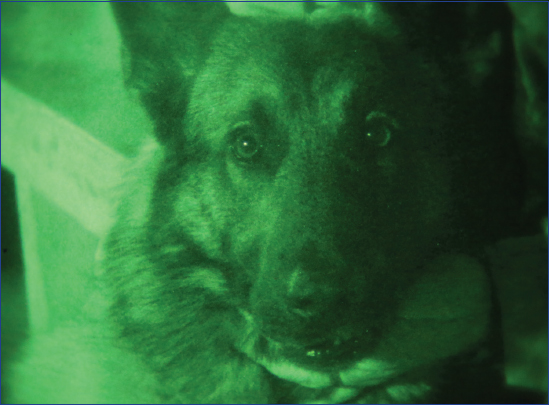

War is a 24 / 7 business. That’s why canine soldiers and their handlers often train under cover of darkness so they’re prepared for anything.

At the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center in Twentynine Palms, California, canine soldiers and their handlers conduct night-training exercises at least once every month. “At night is when the dogs would usually work,” said S.Sgt. Daniel Andrzejewski, former kennel master at the base. “So on top of any other training the handlers do, we also do this night training.”

While many handlers would prefer to work with their canine partners in the light of day, others clearly prefer the nighttime hours. “We’re down and out of the way,” said S.Sgt. Michael Caruso, an MWD handler who works alongside his partner, Zody, at the 51st Security Forces Squadron at the Osan Air Base in South Korea. “We’ll be able to see someone and before they know what’s going on, I can notify base security operations to dispatch responders to handle the potential threat.”

Typically, such training is conducted at venues that are not part of the dogs’ regular routines in an effort to challenge their senses and allow them to practice in unfamiliar places.

“We plant the [training scents] … in different locations throughout the building and let them sit there for about thirty minutes,” Andrzejewski said. “After that, the scent has had time to spread around the room and give the dog a better chance to find it. Most of the time, the substance will be sitting in a hiding spot for a longer period of time.”

Perhaps the most commonly used photo in stories about military working dogs is one that shows them in action, that is, biting the arm of a pretend bad guy. Certainly, showing a picture of a snarling, growling, tooth-baring canine can be an effective way to demonstrate the essence of what a military working dog is capable of and why the military values them so much, but the truth is that it’s rare for a canine soldier to get a chance to bite an actual villain outside of training.

In short, MWDs are trained to bite because it builds and displays aggression in a dog, which is a required personality trait for all canine soldiers. Though similar to the firearms practice and training that law enforcement professionals endure, it may never be necessary to fire a gun in the line of duty.

“Aggression and biting are skills we need the dogs to have even if we aren’t going to use it,” said S.Sgt. Charles Hardesty. “It’s all about building confidence. If the handlers are timid, the dogs are going to sense that and act the same way. We have to build their confidence and then reinforce it with positive feedback.”

“We like to take it step by step with aggression,” said S.Sgt. Daniel Andrzejewski. “Training varies from dog to dog. We work them up with different biting wraps because we don’t want the dogs to become gear dependent.”

Whether a handler opts to use a bite sleeve or a full-body bite suit that tends to make the pretend “bad guy” look like the Michelin Man, depends on the trainer and handler as well as the specific exercise, but the actual bite is only the beginning of the training. S.Sgt. Conan Thomas and his canine partner, Sgt. 1st Class Britt, continued their training while deployed to Iraq from Fort Carson, Colorado. “Britt is trained on a bite sleeve, but we like to use a whole bite suit just for the safety of the decoy,” said Thomas. “How a [human] decoy acts when he goes down is important to make the training good for the dog. The drive for the dog is the bite, and he can’t bite without us having at least a bite sleeve.”

As is the case with other facets of MWD training, the handler learns just as much as the canine, sometimes even more. “Getting bit by your dog allows you to understand what the suspect is going through, just like when we use Tasers and pepper spray on one another in training,” said S.Sgt. Gary Cheney, a handler with the 633rd Security Forces Squadron at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia. “The tactical bite suit made it more realistic. The dog recognizes the suspect is in pain and knows what to do.”

In addition to the certifications and tests that every canine soldier has to pass on a regular basis, many also participate in regular competitions and races that pit them against other MWD teams—and sometimes civilians—so their handlers can better determine just how fit they are and how well they work together.

Some of these contests are produced by outside sporting groups and nonprofit veterans’ organizations, but a handful are run by the Department of Defense. These Military Working Dog Trials offer MWD teams from military bases from across the country the opportunity to compete in a series of events that test their mettle in both speed and form. To be sure, these contests can be quite grueling, but it was the Iron Dog competition, a demanding six-mile obstacle course where handlers are outfitted in full combat gear while wearing a rucksack that contained a thirty-five-pound sandbag, that served as the true challenge for both human and dog. Once they’re geared up, participants were required to run through often rough terrain—occasionally hoisting their canine partners onto their backs—rescue a lifeless body from a vulnerable area, and crawl under barbed-wire fences while simulated gunfire screamed inches above their heads.

“[The competition] allowed us to handle scenarios we may actually come across here or while deployed,” said PO 1st Class Ekali Brooks, an MWD trainer with the 341st Training Squadron at Joint Base San Antonio–Lackland.

Brooks—who won in two categories and was awarded the overall title of “Top Dog” following the three-day Military Working Dog Trial at Lackland in 2012—added that despite every competitor’s desire to win, or at least finish, the Trials and Iron Dog course also served as a valuable training aid for each and every handler. “We were able to help each other by pointing out the good or bad things we saw. In the end, it makes us all better handlers,” he said.

Marine S.Sgt. Jessy Eslick, who works with the Defense Department’s Research and Development Section, said that watching the competitors—both human and canine—made him realize that despite standard MWD training practices every MWD team is required to meet, a great deal of diversity in training techniques and maneuvers is employed by trainers and handlers at bases across the country and on deployments.

“The dog world is changing every day and we need to stay on top of the new technology and training techniques,” said Eslick. “That being said, we have some work to do to improve and learn from the handlers and trainers before us. I have pride in being part of such a special group of individuals who are dedicated to improving every day. When the time comes and you’re asked to go out on the front lines, you know that you and your dog are there to save lives. You can’t ask for a greater responsibility than being a dog handler.”