Though MWD handlers speak a language all their own when it comes to communicating with their canine partners—often without opening their mouths—they must frequently interact with people who have no idea what life is like with an MWD or, indeed, what to expect from a simple encounter. “Can I pet the doggie?” most ask, or maybe they’re afraid of all dogs, especially ones that can look so ferocious.

That’s where the role of public affairs comes in, where handler and canine set out to educate both civilians and fellow military personnel and staff on exactly what these dogs are capable of, from charging a bad guy in a bite suit to rolling onto their backs for a few well-earned belly rubs.

“Letting people know what we do and that we’re here to help them, helps us,” said Cpl. Darren Westmoreland, a handler at the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center in Twentynine Palms, California. Plus, having the dogs interact with—and occasionally show off for—civilians only enhances their training. “Putting the dogs into a scenario with a crowd helps them train [because they] … still have to perform their tasks regardless of people’s reactions,” he added.

Public affairs demonstrations can include everything from participating in a library program designed to help children improve their reading to running the dogs through their daily training regimen at a demonstration on the grounds of a local county or state fair. Public affairs also extend to deployment, when human and canine soldiers in a war zone can help ease the stress and strain of the situation by showing local civilians that these dogs, while professionally trained as soldiers, are not something to fear.

“We’re here to show them some of the capabilities our teams bring to the troops in the field,” said S.Sgt. Jeffery Worley, kennel master at the Marine Corps air station in Yuma, Arizona. “We’re out here showing them what we can do, what we love to do. It’s always a privilege to show what our dogs are capable of, and help people better understand what it is we do.”

Sometimes reluctant readers need a nudge of encouragement to help them pursue what they often find to be a difficult task, whether it’s reading an entire book by themselves cover to cover for the first time or tackling a higher reading level. If that nudge comes in the form of a wet nose, furry body, and marvelous jumps and leaps through the air, so much the better; more kids just might be persuaded to pick up a book and soldier on through.

At the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center in Twentynine Palms, California, a German shepherd named Colli served as a welcome and inspirational reward for the kids participating in Paws for Reading, a summertime reading program at the base library, where librarians joined with the MWD teams on base to provide a draw for kids in the form of a working-dog demonstration.

And what an incentive. As the kids crouched on the edge of a field, several handlers ran their dogs through their standard obedience routines and the onlookers gasped, laughed, and applauded. But once the bite suit came out, the kids sat up straighter and were clearly riveted. A handler in the bulky suit started to run while another handler held Colli and riled him up before releasing him. In a matter of seconds the dog was hanging off one arm growling and snarling while the “perpetrator” wore a huge smile … along with the children.

“I love using our on-base resources to provide different events for kids,” said Ursula Morales, program coordinator at the base library. “The program helps younger children stay engaged in reading over the summer to avoid what’s called ‘summer slide’ where students will regress in their reading if they don’t keep their minds active. To avoid that we include incentives to keep participants interested.”

While there’s a fair chance that kids who live with their parents on a military base have already seen canine soldiers just by virtue of living there, the same can’t be said for civilians in the local community.

So it makes sense to introduce the public to the talents and skills of canine soldiers at an event where people normally come to see and visit with other animals as a matter of course. For many people in Washington State, that event would be the annual Puyallup Fair at summer’s end. Traditionally, in addition to the livestock exhibits and ox pulls, the fair also showcases other animals, including dogs from rescue groups and guide dog organizations, so a group of MWDs from the nearby 51st Military Police Detachment at Joint Base Lewis-McChord fit right in.

“The goal was to put a face with the military canine program and working dog teams here,” said handler Sgt. Todd Neveu, who works alongside S.Sgt. Gizmo, a German shepherd. “Puyallup wants to showcase the local dog handlers and we are a part of that, showing what our dogs can do.”

Hands-on demonstrations that provide local residents with a chance to pet the dogs, interact with them up close, and ask questions of their handlers also help to defuse any natural tension that civilians might feel when they see a police car carrying a dog out in the community, whether it belongs to the military or local police force. Across the country from the Puyallup Fair at the Army base in Fort Campbell, Kentucky, handlers and their canine partners often visit local schools and community organizations to give talks about the MWD program. S.Sgt. Jonathan Rose runs the MWD program at the base and says it’s a good chance to build bonds between military and locals.

“It shows them that we’re here and we’re available, and it teaches them about the capabilities we have,” said Rose. “A lot of people don’t know who we work for or what we do. They think we just drive around in patrol cars eating doughnuts and drinking coffee. I’m just showing them the other side of the house. Besides, this is a job in the military that they might not know that is available to them.”

Although securing a position as part of a MWD team in any branch of the military is highly competitive among humans as well as canines, the various branches never stop recruiting for new members; after all, it’s the only way to find the absolute cream of the crop. As a result, many MWD units hold regular demonstrations for prospective soldiers, often for members of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, who are based on college campuses, as well as its junior division program at high schools across the country.

This form of community service can also cross borders. When a group from the Canadian Air Cadet Program, a youth program similar to JROTC, visited Joint Base Langley-Eustis in Virginia, they got a behind-the-scenes peek at operations on the base, but they especially perked up when the MWD demonstration began.

“It’s important to share our American military culture with our international allies so they can get a better understanding of the way we operate,” said Tech. Sgt. Mark Leslie, the kennel master at the base who led the demonstration. “While conducting joint operations, many service members have the opportunity to work hand-in-hand with other nations, and sharing our culture and understanding each other is a necessity to working together.”

One of the Canadian cadets, Rolan Naiman, a warrant officer with the 180th Mosquito Squadron, thought the MWD demonstration was a perfect way to showcase the breadth and diversity of the U.S. military. “Within our cadet program, we can be in our own ‘bubble’ in Canada,” he admitted. Since the Canadian Air Cadet Program actively encourages the idea of building connections with military personnel and civilians throughout the world, providing their service members with experience and demonstrations give cadets firsthand experience and may just spark an interest in becoming a MWD handler on their own.

The handlers who give the demonstrations also benefit. “Personally, I like having fun with the kids while also trying to teach them something about the mission,” said Leslie.

It’s all well and good when demonstrations that spotlight the amazing things that MWD can do are essentially preaching to the choir. But it turns into a much different—and potentially tense—job when a handler uses her canine partner to reach out to a person who may have been afraid of dogs his entire life. Even more difficult is bridging the cultural gap with people who grew up in a society that teaches that dogs are unclean and have no place interacting with humans, much less living in the same house with them. Indeed, in some Arab cultures people believe that if a dog eats from a plate that humans eat from, the plate must be scoured with sand and placed in a sunny spot for forty days in order to purify it.

So MWD teams who serve in Muslim countries in the Middle East, such as Iraq and Afghanistan, must overcome a centuries (indeed, millennia) old distrust of dogs. Add to this the fact that many residents of Iraq and Afghanistan view the military as invaders and occupiers and the presence of a dog adds insult to injury in their eyes. For handlers and their dogs on deployment, this is obviously a trickier situation than setting up a couple of high hurdles and donning bite suits in order to display their talents and win the crowd.

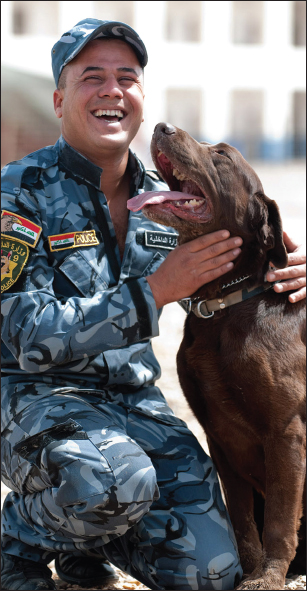

One way that U.S. Coalition handlers have worked to bridge the gap in recent wars and conflicts is to help the Iraqi and Afghani police form their own MWD program and train in clear view of locals, helping them to realize that if one of their own could work with a dog to help fight terrorism in their own backyards then maybe dogs aren’t such a bad thing after all.

In the spring of 2010, Coalition forces paired up with a team of five Iraqi police officers with five dogs and, after just six weeks of training, the teams were already succeeding in finding reserves of explosives and bombs hidden in neighborhood houses. As curious residents gathered to watch Mahmoud Ismail Husain, one of the first group of five, search local buildings with his canine partner Bally, a Belgian Malinois, Husain soon found himself teaching his neighbors what his dog could do, things he had just learned himself a few weeks earlier.

“I encourage them not to fear the dog,” said Husain. “I tell people that Bally is a working dog and he is here to protect our country. He doesn’t bite—he finds explosives.”

And just like his more experienced MWD handlers, Husain never stops being amused and entertained by his canine partner. “When I laid eyes on him, I knew he was going to be my dog just from his stance, he was very athletic and hyper,” he said. “Bally is a troublemaker. When he gets hold of his toy, he doesn’t let go. He makes me very tired.”

But it’s not only the police and military who are helping people in Arab countries learn that dogs are not to be feared. Operation Outreach Afghanistan, an organization that provides humanitarian support and equipment as well as food and clothing to Afghanis throughout the country, is also spreading the word about MWDs.

The group regularly schedules Kids Day for local children, including pizza for lunch, English lessons, and demonstrations by Coalition canine teams and military veterinary staffers. While they didn’t bring out the bite suit, they did show the kids how to care for a dog, from feeding to grooming, and even held an informal dog show that featured the MWDs. For some kids, the highlight of the day was when they donned a stethoscope and listened to a dog’s heartbeat for the first time.

Though it’s clear that the vast majority of nonmilitary who view a canine demonstration thoroughly enjoy seeing the dogs strut their stuff, perhaps the audience that appreciates them the most consists of other military veterans.

For the MWD teams from Camp Lejeune in Jacksonville, North Carolina, one of their favorite ways to give back is with demonstrations for groups of local veterans from World War II.

“All of our guys are veterans, so we know what it means to be a veteran,” said Trent Tallman, a handler with the team who likes to incorporate a history lesson of sorts into his talks, describing how the duties of the dogs who served alongside the veterans differed from those of today’s canine soldiers.

“It’s neat to see the energy and it’s good for us too,” Tallman said. “Sometimes you get an audience that doesn’t really seem to care, but not with this crowd. We want to stay as long as we can and make sure we answer every question.”

And clearly, the intensity of the attention and interest from the audience is not lost on the dogs. “They feed a lot off of the crowd,” said Tallman. “If they are cheering and clapping, then the dogs will be into it too. Nothing makes me prouder than when we get to go up in front of a group of veterans, especially World War II veterans.”