Out to Maureen’s to babysit Stephen. When I go out there, all the horses crowd around because they know I grind the oats for the cattle, so I give them all a handful. You can give a cow a bushel of oats or feed and she won’t likely remember you unless you do it regularly. Not so a horse or goat, they never forget.

A horse will sometimes forgive an injury but a goat never. Hurt him and he’ll get back, sometime, somehow. I talk too much about goats, but did I ever tell you about old Father Dubeau, the priest at Sandy Lake? He had all sorts of animals around and was good at training them. There was a boardwalk from his house to the church, and the father would walk up and down reading his breviary. He’d be followed, honest, by a big brown cat, a huge black dog, and a billy-goat, up and down. As long as the father walked, his animals would follow. He tried hard to get a big white rooster to join the procession, but with no luck. He said the rooster was likely a Protestant.

The black dog, Mackush, was a bit of a marvel. Father would give her a note and tell her to take it to the brother or the teacher, and she’d go to the right place. She’d bring notes over to me on the other side of the bay. She could open and close doors. Brother had made latches she could operate. In winter, she’d go to the fish shed, pick out a fish, take it to the rectory, go in the kitchen put her fish in a pan that they kept under the stove for her, wait till it thawed, then take it outside to eat. She’d open and close every door on the way. The father had a bad heart and would have problems at night. The dog would immediately go fetch the brother if the father appeared to be in difficulty.

She was an Indian sleigh dog, no special breed, but quite a dog. The father used to tell me how he noticed that he was losing a lot of turnips out of his garden. The native women used to come and go that way from the camp, but no one ever saw them with turnips. But one day a woman came to visit with a baby in a tikinagan. The dog was very interested in the baby, so much so that Father Dubeau decided to take a look himself. He hefted the tikinagan and it was very heavy. Inside he found not only the baby but a few of his turnips. He told us about it and said with a twinkle, “That woman was a Protestant too.”

It’s nice to be able to get out and do the things I used to do so many years ago. Then, tracking animals was a skill every kid learned at an early age. How to hunt was important. There were no butcher shops, and while there was salt meat for sale in the store, fresh meat had to come as a result of someone’s lucky or careful hunting.

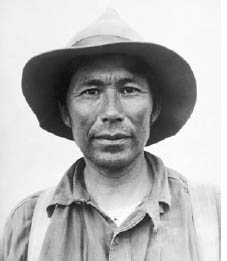

There was a little Eskimo man, his business name was Joseph Palliser, the surname given to his grandfather by Governor Palliser many years before. His native name was Kejuk, meaning wood, because he was small and neat like the wooden dolls they used to make. I once went caribou hunting with Joe. It was mid-winter. The caribou were high in the mountains where the wind kept the snow blown off the moss. There were a lot of wolves, and the caribou knew it. They were very shy.

The only sign to be seen of caribou was the odd frozen dropping, and they could be an hour or a month old. Caribou don’t have the best of sight and always graze into the wind to take advantage of their 20/20 nose power. Joe wasn’t very tall. His nickname was Little Joe to distinguish him from Big Joe, who was not a giant, about my height perhaps. Little Joe said being short just put his eyes that much nearer the ground, the better to see any game signs. It wasn’t long before he said we were behind several caribou. One big stag, the rest were does or young stags.

The ground was frozen like iron. There was almost no snow. He pointed out a scrape in the lichen on a rock. I’d never have noticed it, a bit like a fingerprint on an iron rail, could be anything, but on we went. After about half an hour, in which I followed Joe with my rifle ready and my mind in a cosy camp in some sheltered valley and very little conviction that we’d ever catch up with Joe’s phantom caribou, he pointed out a little patch of snow that had accumulated in the lee of a small boulder, and there, sure enough, was the print of one caribou hoof. We must have come a mile in that blizzard and all that could be seen with the wind and drift tearing at our eyes was the odd depressed place in the moss, a scrape on a rock, a few crushed Arctic willows, but we had come surely to that one foot print.

The wind was so savage that it was impossible to look ahead. Our hoods protected our faces, though I suppose my kabloonak nose stuck out a bit more than Joe’s arctic modified beak. I wondered how the heck we’d ever see the animals and how it would be possible to sight along the barrel of a rifle with those ice spicules coming like shot.

Joe gave me to understand that we were close. I guess I looked unconvinced and he turned his head so that instead of blowing straight into his face, it blew past the front of his hood. He motioned me to do the same and touched his nose with his finger. In a second or so I realized that I could smell the strong caribou smell, almost like farm animals. They were upwind and invisible in the drift but close, very close.

Joe headed off to the right and motioned me to go left, walking almost sideways. I watched him doing the same for a few seconds before he vanished in the blowing snow. In another moment or so, I thought I saw him coming back so I stopped, and then realized that what I was seeing was a caribou facing down wind, listening. Somehow he had sensed our presence. I brought up my rifle and was about to shoot when I heard a muffled report and my caribou went down. I knew the rest would have gone. Since I’d never seen them, I had no idea where, but caribou are strange animals. They’ll dash off madly when scared, and just as likely double back in a short while to see what had scared them.

So I stood waiting, and after what seemed to be hours but was likely only five minutes or so, I saw shadows in the snow racing back and coming to a stop almost in front of me. By now, the little light that we’d had was failing into the night. I picked out what looked to be the largest animal and fired. I had the satisfaction of seeing it go down. The others were gone by the time I’d reloaded.

So there I was. I had my deer, but where was Joe and his animal? I needn’t have wondered. Out of the dusk and the storm came Little Joe, grinning from ear to ear. He knew he’d probably see the first caribou and it was a great joke to him to shoot it under my nose.

We were talking about tracking, weren’t we? Well I’ll tell you, we skinned and cut up those two caribou, took enough for a meal and one for the dogs. By that time it was pitch dark. Joe said, “Go home for supper,” and started off. I followed his shadow and never walked a longer mile in my life. Dark? It was absolute blackness and there were rocks and things to be wary of. It’s no joke walking in the dark over rough country. You lift a foot and expect to put it down on the same level as its mate, but you find it brings up much sooner than you had anticipated. You are standing with one foot on a boulder, what do you do now. Put the other foot up there too, or bring the first one back? Decisions, decisions. But that was nothing to the fact that I wondered if Joe had even the slightest idea where we were. Again, not to worry. The first thing I knew I was stumbling among the dog traces. They, sensible animals, had gone to sleep, hardly expecting to see us until better weather and more light.

In a short time we’d built up a snow wall, since there was no hard snow to make an igloo, and put our komatik wrapper over the top, fed the hungry dogs, and were sitting in our makeshift shelter with a primus stove going, watching the meat cook by the light of a candle.

We needed six caribou, and in the next day or so we got them, all except for the last day in blizzard conditions, but Joe acted as if he could see for miles. He’d pick up tracks, decide that they were fresh enough to follow and we’d be away. The last day the weather improved, and it was possible to see where we’d been hunting. To me it was a wonder that we hadn’t been killed by falling over a cliff and said so to Joe. He just laughed and said, “When you follow caribou in drift you not got to worry. He don’t fall over cliff, so you don’t too.” Well and good for someone who could not only see in the dark, he could see tracks where none existed.

We picked up all our meat and headed back. On the way out the valley, in the first trees that we saw, we found a party of white hunters who’d been there for days waiting for the weather to improve. They were experienced men who knew that there was no chance for them until they could see. They weren’t a bit surprised to see that we had got caribou. Joe never came home empty handed. On one of our last camps I said something to that effect. He said, “Most times I do good enough, but once old black bear he beat me.” Seems that Joe had a net some distance from where he was camped. It was late fall and there were not many salmon, but he’d get two or three every day. He was salting them lightly in preparation for smoking for his winter breakfasts. So he had a barrel full of weak brine near the net.

Several times he put salmon in the barrel and as regularly the bear would come at night and help himself. Joe tried everything, deadfalls, traps, but as he said the bear was too cute. That being a Labrador expression meaning smart.

Well he was getting no place and the sealing was good so he couldn’t stay there and wait for the bear. Also I figure he was too stubborn to just take the fish home. So he said, “I got big old double barrel must loader (muzzle loading musket). He set it up and attached a line to the triggers and arranged it so that the bear would pick up a salmon, pull on the line and shoot himself. So Joe said he was sitting at home smoking his pipe, when bang went the old blunderbuss. He waited for the second barrel but not a sound, and he figured he’d gotten his bear. It was a bright moonlight night, so he decided to paddle across to see his victim. He said, “I paddle very quiet, big moon, I can see good. Then I see that bear, he standing up, and I see he got the gun. You know what that bear do? He find the gun, shoot one barrel so I come running to see him dead, and he ready for me with second barrel. If I walk over, not paddle, he shoot me sure.”

I said, “Joe, if old Uncle Joe Michelin hadn’t told me that story I’d believe it happened to you.” Joe looked at me very solemnly and said, “That old Joe Michelin he steal my story. Never mind, he old man, not live long, then I tell my bear story some more.” But by a lot of different camp fires in very different places, Joe told me many yarns that were true, perhaps not exciting to a lot of people, but stories that were impressive when one remembered the amount of knowledge and ability that little man had stored up in his head.

I remember once on a trip stopping at Joe’s house. There was a travelling minister who happened to arrive at the same time. He was telling us about an accident up the coast where a girl out hunting ptarmigan had slipped on the ice, dropped her little .22 rifle, which had discharged and the bullet had gone through her skull and lodged between the skull and brain. The parson and a doctor happened to arrive shortly after the girl’s father had found her. He told us how, by the light of a flashlight, the doctor was able to remove the bullet and move her to a hospital by dog team where she was recovering. Joe thought a while and said, “Pretty cute, that doctor.” The parson said, “Yes, but he spent nearly ten years of his life learning to do that sort of thing.” Joe said, “When I’m small boy, my father started teaching me things. All the time I learn some more every day. I getting old man now, sometimes I think I don’t know very much.” I guess his life was one long learning process.

Like all his race, there was genius in his hands. He could make and fix. He could handle a boat or dog team so that he was noted in a country where these things were an indication of a man’s worth. He could watch a clerk add up a long counter slip in the store, and even though it was upside down, he’d have the answer, and correctly, before the clerk, and he never had a day of formal education. He learned somehow to read and could write a letter in English or his own language.

There were several Joe Pallisers. He always signed his name Jos. Palliser of John. Last summer, when Doris Saunders of the magazine Them Days was here, and she and I were talking about many of the people that were around when I was young, Kejuk’s name came up. She’d never heard of him, but when I said Jos. Palliser of John she knew immediately. He died only a few years ago, and before he went she recorded a lot of his memories. I asked about the bear and the musk-loader. She hadn’t heard it, not from him or Joe Michelin, who I believe was the original liar, so I gave it to her as I remember it. It should go in Joe’s dossier.

Speaking of Joe Michelin and lies, he once told my dad that when he first came to Labrador the curlew were so numerous that a man could fire one shot and get enough to give him a curlew every Sunday for a year. He said, as a matter of fact, that once he had fired one shot and picked up ninety-nine birds. My dad said, “Might as well say you got a hundred.” The old man looked shocked. “What, tell a lie for one lousy curlew?” So there was Uncle Joe Michelin, who wouldn’t tell a lie but could spin yarns of his days in the lumber woods in Quebec that rivalled Paul Bunyan. In fact, they were so close to the Bunyan yarns that you’d think they were the same. They couldn’t have been, Uncle Joe didn’t tell lies.

You guessed it, yarn spinning was a favourite evening entertainment where there was no radio or TV and only a limited number of records for the few old wind-up gramophones. Old Uncle Jesse Flowers, one of our principal yarn spinners at Rigolet, used to say, “Now I can’t guarantee this is true, but a man who never in his life told a lie, told me.”

Was to the market this morning. Have to admit the market does have lovely blueberries. They should, at the prices they charge. One of my favourites too. Rigolet was a great place for berries of all kinds, and the late fall blueberries were a great target for the fall geese. We’d try to get what we needed before the hungry young geese came to the coast from inland. They soon scoffed the blueberries and went after the low bush cranberries, marshberries and bake apples too.

Greed did get the best of them though and a good few ended up in the oven because they were too busy eating to watch for hunters. We always kept the biggest fattest goose for Christmas. We had a special airtight box to keep fall meat in. Using a mixture of ice and salt we could freeze a bird early in the fall and have it in perfect condition for Christmas. My dad insisted on goose for Christmas and salted salmon for Good Friday. The other holidays got what we happened to have.

I wasn’t very old when a lucky shot got me a big Canada goose. Can I really remember it? Not only can I remember the actual stalk and shooting, I can remember how my breath hurt in my chest, how my hands shook with excitement. I knew I could never hold the gun steady, but at the last moment I found that I could. As I’ve said so many times, we were brought up to hunt. We had to, and because it was a necessary part of living, there was a wonderful joy in bringing home a Sunday dinner.

I can still taste that first goose. My dad carved at the table and he served the meat from the platter. My mother served the vegetables. I can see him now as he laid that crusty gold slice on a plate and passed it to my mother. “First cut to the hunter.” There were several clerks and employees and my dad at the table, all adults, all hunters, but it was my goose, my first one. I was alone when I got him and he was a heavy lug back home over the hills and through the marshes.

I put a good many more on the table later on, but that is the one that I remember. I got home late, after dark. My mother always worried. They had just about finished supper when I turned up. Mother heard the door and came out, relieved that I was back alive, and in her relief inclined to scold me for being late. “What kept you?” I can’t tell you the pride that was in my heart and in my voice when I said, “This old fellow, I think he weighs twenty pounds,” and I dropped him on the floor as if I’d brought a hundred others home. I got a wash and went in to the dining room and got seated.

My dad started serving whatever there was and old Mr. Parsons, the customs officer, who ate all his meals at the house said, “Any luck, boy?” I said as modestly as a ten-year-old who has just got his first wild goose can, “Oh, I got a goose.” The old man, a retired ship master said, “You did, well I’ll be damned,” then quickly to my mother who wouldn’t have swearing in the house, “Saving your presence my dear,” and he had to know where I got him, how, and all the details. He said to my dad, “We got a coming hunter here. Remember that when you have no further use for the rifle.”

That almost brought tears, because the rifle in question was one his son, Ralph Parsons, the last fur trade commissioner of the HBC, and my hero, had given his Dad years before. When Uncle Bill’s eyes gave out, he gave the rifle to my dad. It was a beautiful gun, and if I’d ever been asked what the thing I most wanted would be, I’d have said a .22 high-power savage. And now it was going to be mine, not right away perhaps, but I would own it one day.

Sure enough, when I was in Hebron my dad decided the time had come and he sent it to me. It travelled with me a number of years. I left it at home when I went into the army, and after the war I was going to Igloolik from Churchill so my folks sent all my things from Labrador on Nascopie and she was lost on the way in. I grieved for that firearm, but somehow it was appropriate. Ralph Parsons, the Nascopie and that gun opened up the Eastern Arctic. I don’t mean that the gun played any significant part, but it was there, and since R.P. was long dead, what better place for the gun to rest than on board Nascopie, my favourite ship, on her last voyage.

I wish I had some new or exciting news, but things don’t change much. One more month of summer and we’ll be looking at frosty nights again. Used to be that was just another joy, especially with the fur trade. The trappers would be getting restless and one by one they’d disappear, nothing left in the summer campsite except bare poles and floors of wilting spruce boughs. An abandoned Indian camp is a lonely thing, mostly because they leave the poles behind. Even in summer, to suddenly come across an empty muskrat trapping camp is an odd sensation. There will be weeds and new poplar half way up the tent poles, but the signs of life are still there. A broken toboggan board, a pile of shavings where some one made a paddle, a few tin cans strung together and hanging in a tree, saves Mom calling the kids back before they wander too far. A jangle of the tin ware means get back here—quick.

Eskimo camps aren’t lonely. There are no tent poles, nothing is left, a ring of stones that marked the tent, that’s all. Eskimo country is so big and open that there is no place for loneliness I guess. For me it’s possible to feel quite alone in the bush, never in the barrens or the Arctic, but I can’t tell you why. The loneliness of the bush is a good loneliness though, especially at night, when all the trees crowd a bit closer and gossip under the stars.

They watch you too, you can feel it. Marjorie MacDonald, “The Egg and I,” said mountains watch you too. I’ve felt it. It’s an impression you get. If you come at a mountain across a wide valley, it seems to stare at you, and as you get closer and closer it seems to bend over to look at this strange little thing that’s crawling around its ankles. Okay, so it’s the changing angle that convinces you that the mountain bends over. If you are alone, it’s kind of nice to have a friendly mountain watching your progress, just the same as it’s nice when you are all nicely bedded down in the bush to have the huge spruces move a bit closer and stand with their heads together watching the tiny spark of your candle. And when you put the candle out and the fire dies, you can hear them whispering together, with maybe a big old horned owl chuckling to himself at his own jokes.

You know a horned owl can make more strange noises. His hoot is quiet and mournful, but the rest of his tricks can amaze you. He can make a noise like running water in the middle of winter, imitating a creaking tree in child’s play, and once in a great while a mad person’s laugh that can scare the boots off you. Poor old Mr. Bunny will be quietly ambling across a moonlit clearing, minding his own business, when this mad woman screams right beside him. He isn’t wise enough to streak for the nearest cover. No, he sits upright and his black shadow on the snow tells Mr. Owl what he wants to know and bang, midnight supper.

I once spent a night in a tent with crazy John Michelin, a man who’d do anything on a dare, who was one of the best woodsmen in the Height of Land trappers. He could walk further and faster, carry heavier loads than anyone else and laughed and joked the whole day long. Well, John put a candle low on the ground inside the white tent and he made rabbit shadows with his hands on the canvas. After a while, we could hear two owls talking together about the funny goings on. After a while, they decided to investigate and they came over low, almost touching the tent. We could see them by the light of the moon, and their shadows made breath-catching cruciforms on the canvas. You’d have loved them. Great outstretched wings, and in the clear moonlight, the taut wing feathers were faithfully reproduced for a second on the tent roof. A second of intense beauty and motion.

They never came back, but that second is frozen forever in a special chamber in my memory. Not a sound, just a sudden flash of black shadow, one just slightly ahead of the other. Flat images one would say, no indication of the fierce eyes and claws or of the big soft bodies in perfect soundless flight. In my memory I see them as two black cut-outs in the sky, giving for one moment a glimpse into a world of mystery and motion. I don’t suppose there is a camera made that could record that moment, or an operator so skilled that he could catch it. I’m glad too, because it’s mine and I wouldn’t want to see it reproduced in Life over some silly caption.

From the sublime to the ridiculous. I was once, in my Easter holiday, given the job of taking the travelling doctor from Rigolet to West Bay, where he’d be picked up for the next relay along the coast. I had our travelling team, twelve or fifteen big dogs and an excellent leader, with a light komatik. The middle-aged doctor and I sat aboard and the dogs romped along in great style. As we had a light load, the first fifteen miles was along the shore with pretty well perpendicular cliffs on one side, and a few feet away on the other the open water of the inlet which, due to strong tides, seldom freezes.

I had been brought up on the ballicaters, as the narrow ice foot along the shore is called. The doctor had seen little of the same on the playing fields of Eton. He hung on for dear life and cringed when we made a sharp turn to go around a corner and the back end of the komatik and his long legs hung over deep freezing water. Almost no one ever actually fell in, so, though he knew it not, he was in no danger.

When we got to fast ice, deep, firm and with no water to be seen in any direction, he confided to me that the terror mark of all his winter travelling was reached when he left Rigolet “bound up the bay,” and again in summer, when his little ship was buffeted by the tides and whirlpools that kept the “infernal” place open in winter. I rode a long mile or two digesting this, as I’d always been of the opinion that we at Rigolet had the best of possible worlds. Winter and its delights on one hand, and on the other, open water that brought us our share of seals and eider ducks all winter as well as some of the more cold resistant fish like smelt and trout.

Anyhow, that’s not what I started to tell you. The second day out, as we were spanking down the back way, we caught up with Israel Williams. He deserves a little description.

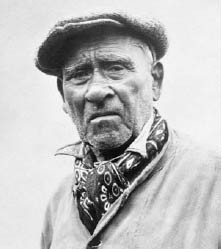

The grandson of an old HBC seaman who decided one fall to remain on Labrador and marry an Eskimo woman, Israel was one of the hairiest people I ever knew. He was also not quite the average model. He was short, very broad, with exceptionally long arms and a bent spine. Standing fully erect, Israel could touch his knees with his palms. All you could see of his face was the tip of a red nose and two black eyes. The hair and beard looked like an enormous black mop.

Shy as a mouse and timid, he lived in a place called Flatwater with his brother Tom and his family. It was an out of the way place so they saw very few people. Their women and children were even more shy. They were good trappers and fishermen, but even though they had a good income, due to their odd shapes, clothes purchased or even made at home never fitted very well.

So, away out on the ice of the back way, we fell in with Israel. He’d been to Rigolet to stock up on grub to last them over the break-up season. He had a small team of small dogs. He lived too far from salt water to get many seals, which meant his dogs ate mostly fish, not the best diet for working dogs, who thrive on the meat and fat of seals. He was poking along at a snail’s pace, using a pole to push on the back of his komatik to help his dogs a little. It was a warm day, the sun was bright, the snow soft, and his heavily loaded komatik wasn’t long enough to “bear up” as we used to say and it was ploughing along half-buried in snow.

Israel’s place was of course one of the doctor’s calls. He visited every house and camp along the coast. As a matter of fact, we had expected that our second night out would be spent at Flatwater. So we pulled up alongside Israel, and I loaded all his freight on my komatik, which was twice as long as his and had ten times the dog power. He said the river at the end of the Back Way was bad and that we should wait for him there as he knew where all the good ice was.

We went on ahead, and when we got to the river, Israel was nowhere in sight behind. Both the doctor and I had previously spent nights in Israel’s tiny crowded cabin, which was dark and airless. It seemed to be just too much when we had a beautiful evening coming on and a most inviting campsite right at hand. So we decided to camp there, wait till the night frost had dried the water off the ice and frozen the deep snow on the long portage across the land to Israel’s. The sky was clear, so we made an open camp. No tent, just the shelter of a huge spruce and a big fire of dry wood. We were all set up when Israel and his exhausted dogs showed up. We were well supplied with man and dog food so we gave Israel and his team a good supper. He was a bit amazed that we intended to sleep in “them old bushies,” rather than go on for a couple of hours to his house, but he was tired and very happy to be there with all his goods instead of being miles up the bay struggling with a heavy load. Now you say, we were talking about owls, where are the owls in all this? Well hang on, girl, we’ll get to that. Terrible thought, I may well have told you all this before, if so, “I ’umbly begs your pardin.”

Labrador is a pretty country. Hamilton Inlet, or as it was once called, Esquimaux Bay, is prettier than most other places. We had an ideal place to camp, by the side of a little river that was already half open, and the water rioted madly down between the banks in the first rush of the spring thaw. We could look from where we sat straight up the Back Way to where the hills come down to the Narrows, forty miles away, and above the Narrows there are sixty miles of level ice to the far western end where North West River is situated.

We were blessed with a calm, clear evening, and it was still warm as we sat after our supper watching the sun head for the notch of the Narrows and fit right neatly in, then expire in a blaze of red glory beyond the rim of ice that was our horizon.

The doctor, who was a literary sort of bloke, quoted from a long comfortable sort of poem ending with “and seldom have I seen such a setting of the sun.” I don’t think he got through to Israel, who could neither read, write or figure, but who had an extraordinary pleasant voice and who could sing long painful ballads about sickness, death and jails for hours at a time if you managed to get him started. I tried but he was too shy. Too bad, because he sang them in a dialect long out of normal use. They were brought over from the old country many years before and passed from father to son. The doctor was hoping to hear them too but Israel said maybe his son, Garge, would oblige when we got to his house. George, or Garge, was as short, hairy and ill-shaped as the rest but had a lovely tenor voice.

Once the sun had gone, we built up the fire and sat around in complete comfort drinking a last cup of tea. There is nothing that tastes better than a trapper’s tea. You boil the water, put in the tea, leave the lid off, and hold your pail over the fire for a second or two till the tea boils up once. Only once remember. Tea made like that will taste different and all the leaves will settle to the bottom. That’s only a hint in passing and has nothing to do with owls, what gave you that idea?

We yarned a couple hours away and Israel smoked a short black pipe that was so close to his nose and whiskers that it was a wonder his whole head didn’t go up in flames. He’d take a flaming brand out of the fire and apply it to the pipe and I’d think, this is it, he’ll go this time. How can you tell a man’s wife that his whiskers caught fire and he went out in a blaze of glory. Well he didn’t, I’m glad to relate, and because of the extreme purity of the air, the smoke from Israel’s black plug tobacco was in no way offensive, just a pleasant counterpoint to the smell of the brush (brushies) we sat on, and the tea and the wild marshy smell of the running water. The doctor said it all as he got into his sleeping bag. He said, “May my best friend, sometime in his life, have one evening like this. There could never be two.”

Israel wasn’t too well supplied with bedding. His plan was not to camp outside but to reach someone’s house every night, mostly for the visiting, the gossip and singing that went on. But he had a couple of blankets and he built up the fire and lay close, again awakening in me a fear that I should see Israel immolated before this trip was ended. He wasn’t and I didn’t. We were all asleep in a short time.

Once the sun went down, the frost went to work, the melting stopped. The fire burnt low and sometime in the night Israel’s blankets started to admit more of the night air than he wanted and he got up to replenish the blaze. It had nearly gone out but he raked a few glowing coals together and laid some small pieces of wood thereon, and in order to make it catch more quickly, he got down on his hands and knees and started to blow on the coals.

Now I’ve mentioned that Israel lacked a number of things. One was the services of a barber. I guess his wife caught him occasionally and chopped off a few locks, Sampson and Delilah fashion, but he always had a veritable tuckamore of a head. Well that head was silhouetted against the coals and probably looked like an early rising partridge or something of the sort. A horned owl sitting in a tree saw it and figured, “Well here’s breakfast,” and he struck.

Israel’s mop probably saved him severe scalp lacerations but the bird had dug its claws in, expecting to lift whatever it was that it struck. It just couldn’t let Israel go either, and it couldn’t lift him. It beat the air with its powerful wings and threw ashes and fire all over the place.

The doctor and I woke in a hurry, and my first thought was, He’s gone and done it after all. All I could see was Israel in the centre of a tornado or something. I couldn’t see very well at that. Our fire had produced a lot of fine ash in the hours it had been burning, and most of that ash was presently being agitated by a pretty hefty pair of wings. I wasn’t long in getting out of my sleeping bag, and did the first thing I thought of. I flung one of Israel’s blankets over what seemed to be his head and the turmoil ceased somewhat.

The doctor had a powerful flashlight and by it we could see part of Israel’s head and face and part of the south end of a pretty big bird. The doc was a Britisher, and they like to be brisk, so he said, “What’s the trouble Israel,” and Israel who was about dead with terror anyway said weakly, “A ’orrible big devil bin got me by de ’eed yeer, I be dead for sure!”

Well, by carefully keeping the owl’s head covered, and by shifting the blanket around, we finally found the huge claws still clutching at Israel’s hair which was about the texture and strength of small steel wire. Holding the bird by the leg, I tried to loosen its claw. I might as well have tried to break a steel shackle with my fingers. He had one claw on each side of Israel’s head and was holding on like grim death. He wasn’t moving but now and then he’d make a fierce burping sound that boded us no good if he ever got his eyes uncovered.

Israel was crouching like he was carved in stone. I wondered how long his heart would stand. But doctors are equipped, and this one dived into his medicine box and came up with a big pair of shears. He worked the points in between the bird’s foot, which I held at the ankle, if owls have ankles, if not, at whatever joint they have instead, and after a lot of huffing and puffing, he liberated one claw which still gripped a big ball of pure William’s hair. Then he moved around to the other side and cut the other foot clear.

The rest was simple. I carried the owl a little away from the fire and Israel, set him on a dead tree that had fallen, and whipped the blanket off his head. It was too dark to see the expression on his face. I have an idea that he was displeased. He sat there a couple of seconds balancing on his claws that still clutched a part of Israel, then he took off. I have a picture in my mind of a sadly frustrated owl sitting high in a tree looking at two claws full of a black kinky substance, and wondering what sort of an animal he’d almost got.

There were ashes everywhere, in our own hair, our bedding, even in our grub box. The kettle had been flung into outer darkness and we decided that it was no use in going back to sleep. The doctor checked to see that Israel hadn’t been cut, and Israel put on his big fur hat but had no intention of going any place near the fire.

It wasn’t till daylight came that we saw the damage the doctor’s shears had done. Two great areas just above Israel’s ears had been sheared to the skin. Probably that part of Israel hadn’t been exposed to the sun since he was five or six. The doctor was a kind-hearted man, and he went for a hasty walk out on the ice. He seemed to be having a bit of a problem keeping his composure. Have you ever seen the two pouches on the head of a prairie chicken doing its mating dance? Well Israel was by no means a sleek dancing bird, but he did have two huge white spots on the sides of his head.

There had been a good frost, and with full light, Israel pointed out the safest route across the river and we took off leaving Israel to follow. We made a brief stop at his house to leave his groceries and to advise his wife that he’d soon be along. No one needed a doctor and we went on. The doctor, usually a very sober man, cracked up half a dozen times that morning. He’d say, “I wonder what Israel’s wife thought when he took off his hat?” Knowing Israel and his ways that might not have been for a while, say a year or so. But I bet it made a good yarn over many cups of tea and pipes of tobacco.

Israel finally came to a sad end. He lived close to Tramore, the Wonderstrand of the Viking Sagas, forty miles of pure white sand which rises from the sea to two hundred feet in height. During the war, the US navy, lying ten miles at sea, decided to use it for target practice and they shelled it for several hours. Israel and his family were not in line of fire, but of course they didn’t know that. They crouched in their house till the shooting stopped and found that terror had killed poor old Israel. I guess the Yanks sailed away never knowing they had killed a harmless old man.

I like the name they have given you, and the meaning. Of course, you aren’t the “woman from across the water” to me, but it has a lovely sound.

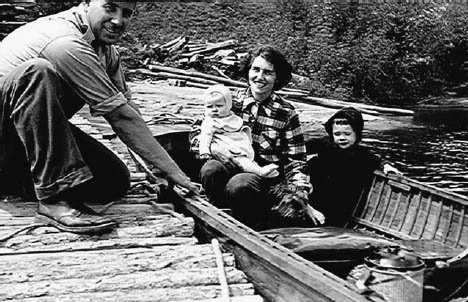

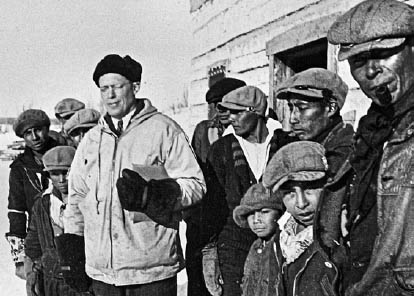

You mentioned Little Joe. Only a few days ago I was hunting for a book on the RCMP ship St. Roche for my niece’s young son, who’s crazy about “old things.” Here now, the St. Roche and I are from the same generation! Well, we’ll let that pass. Anyhow, when I was looking, and making a tour of various books on the way, I picked up a copy of Them Days, and there was Little Joe, at a much more advanced age than I knew him, but not all that much changed. Joe had heartbreaking luck with his first four children, who only lived a very short time. Then his last son was born and he lived and was Joe’s whole world. What Joe knew, he taught the boy. You’d expect a spoiled child, but no way. The child would sit shivering with excitement and anticipation while they drifted in a small boat waiting for a seal.

And when they were lucky, he’d hardly contain himself. He took his part in the hauling out and cutting up. His mother, a very quiet woman, would stand beaming at her two men and their catch, but Joe was the boss. A word from him, and the boy obeyed. I never knew him when he grew up, but if he was like his dad, he was a good man.

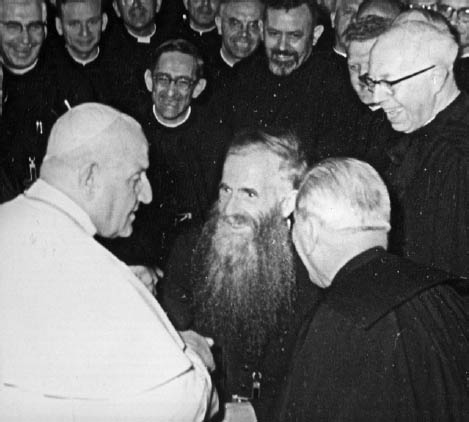

There is something in me that desperately wants to go back to see the sun on the green hills, to see the snow-capped mountains that Joe and I hunted on. I want to go back to the things that cannot change, like old Father Henry, who passed most of his life in the Arctic. I would like my last sight to be across a frozen sea or of an Arctic mountain, but also like good Father Henry, I will not be there at the end. He tried so hard to get his bishop to send him back to the tiny stone house that he built at Pelley Bay. But it wasn’t possible, and a man that gave his life to a cause was denied his last wish. He had never disputed anything his Superiors wanted so he died in a clean hospital bed, with attentive doctors and nurses to care for him, with only one desire, as he told me, to see “my old land.” Not the warm fields of Brittany where he was born, but the rocks and crags of almost the utmost end of northern Canada.

Remember I told you about Mrs. Oldenburg landing and leaving me the bread and tomatoes and Father Henry was having a “fast day”? Did I tell you that later that spring I managed to get a goose, though geese are not common around Repulse. By then, we were getting a few seals and had a little fuel. The only way to cook my gander was to boil him over a fire of seal fat outside the house. I told the father that if this was another fast day I’d feel obliged to write to the pope and complain about his management. He said it wasn’t a fast day so we sat outside on the rocks and fished bits of boiled goose out of the pot till there was none left. Don’t know why I thought of that just now.

I like thinking of Father Henry. When I was at Repulse we had no fuel so we could get barely enough to drink. As a matter of fact, I used to fill a big pickle jar with ice and take it into the sleeping robe with me. Eventually it would turn to slush and I’d get a drink. It was an experience to have that cold glass nest against my back during the night. There are easier ways to waken. Then spring came. Repulse is right on the Arctic Circle so spring arrives slowly. But one day Father Henry and I were hunting up in the hills and found a shallow lake that was about half ice, half water. It was a sunny day, fairly warm by Repulse standards and that water was so inviting. We took off our boots and put our feet in. It was bearable for a few seconds at a time. We had not been able to bathe for many months, so I said we should try. Father Henry’s modesty would not allow him to strip in my presence so he went a little further along and I stripped and tried walking out over the smooth rock that formed the bottom of the lake, but it was impossible. The line of water around my ankles was pure liquid fire. I knew I could never walk in far enough to splash the rest of me, so I went back out and when the agony had gone, at least partly, out of my feet, I found a place where the water was about shoulder deep and I gathered my courage together and plunged in.

I don’t think there was any sensation for a few second; then I was conscious of the most rending pain I had ever felt. I’ve been in icy water many times, fully clothed, and by accident. The clothing helps and the fact that it is accidental helps. One is only interested in getting out, the pain comes later. This time I was unclothed and it was deliberate. The pain seemed to shoot down from the centre of my body to my legs and feet, into my arms. If I could have, I would have screamed but my breath had stopped. To save my feet on the rocks I had jumped in crouched and I went completely under.

The reaction was immediate, and I lost all my strength. I knew I wasn’t breathing and I forced myself to swim maybe four or five strokes, then I shoved my feet against the bottom and shot straight up and managed to get on the shore. Naked as a baby jay, I shot off across the rocks. I couldn’t have stood still and as soon as I got my breath, I let out a yell that could have been heard for miles, I’m sure. I ran around in the sun but I was shivering so uncontrollably that I couldn’t get into my clothes. The only thing to do was run. When I finally began to get some feeling back, I looked around for the father and a quarter of a mile away I could see a white figure with a long beard doing the same dervish dance that I was.

There is no way to describe the searing agony that strikes with the water. It took a long time to regain circulation and when we were finally dressed and warm again, the sensation was glorious. How much accumulated grime came off in that brief plunge I can’t say but we felt wonderful. On the way home Father Henry smiled thoughtfully at me and said, “We are not of very wise mind, Len.” I would find it hard to believe that I would do it again, but many times that spring I went into water that was nearly as cold. I avoided pools with any ice in them. It’s not something you get used to, that’s certain, but such is the power of open water that one does such irresponsible things. I will say that nothing will change a white skin into a scarlet one any faster. I remember looking at my feet and legs and thinking only a tern has feet that red. On the way home we met an elderly Eskimo, and he listened to what we had done and said gravely, “Wah kad lunga,” which can be translated as “How terrible!” but can mean so much more when spoken by a short stocky person who knows every way to survive in the world’s most severe climate, and jumping naked into pools of ice water isn’t one of them. He possibly thought, “…whom the gods will destroy, they first make mad.” If, as I suspect, he saw us running over the tundra in our birthday suits, bright red and gasping strange words in English and French, he probably had a mirthful audience when he told his day’s experiences in the tupik that evening. I can stand under a soothing shower now and remember, even with a little longing, those plunges into that water of fire, and I’ll never forget how I felt after. Mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun. Only Newfies jump into ice water, though what excuse Father Henry had, I can’t say.27

I shall have to see how this goes. Perhaps you’ll turn out to be my wailing wall. Let me say now that nothing is wrong, at least nothing that I can do anything about. Briefly I have just returned from a visit to W.E. Brown in Vancouver. He is eighty-six now.

He is suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. I found it hard. We have been friends and co-workers for years. I admire him very much and he is failing fast, not in a physical sense, but his memory is going. He recognized me and knew Muriel. We talked about old days in the Arctic and in Transport. Then suddenly he stared at me a long time and finally asked my name. I told him and he said, “Not Len Budgell, my best friend?” I had to say yes and that seemed to lift the veil. He was very agitated and said that he was going crazy. I managed to change the subject, and in a few minutes he seemed to have forgotten it. I have just finished a long letter to another of his friends, Professor Rowley of Carleton University, telling him how I found W.E. That wasn’t easy either so I looked around for someone compassionate and understanding and thought of you and how long it’s been since I wrote. I feel better already.

Our trip to BC and back was a mundane sort of adventure but we enjoyed it. Not one leaf had fallen, not one had escaped nature’s paintbrush. Breathe it not to a soul, but there were times when the Rockies were almost as pulsing with colour as Labrador can be. Not quite, but almost.

You would not believe Labrador in fall. Rigolet, where I spent my thoughtless youth, was on a straight stretch of the narrows that connects the outer bay with Hamilton Inlet. Leading straight west is the Double Mere, and almost straight east, the Backway. These are bays fifty miles deep. The hills are high and steep, forested from the water’s edge to the summits, which are bare, but not obviously so. The forest growing almost to the top provides them with a frieze of green, and when the first snow falls, it melts near the water but stays on the higher hills, providing a contrast of white and green. The trees are largely spruce and fir, but there are expanses of birch, larch, aspen and dogwood, as well as the various berry trees. In some places there will be a bold swath of lighter green from the top of a hill to the water. These are the birches. The colour is quite noticeable in summer, but with the first frost they become swaths of gold and red, painted in one stroke by a gigantic brush. The only way to experience it is by boat. You can sail far enough away from land so that you can see every colour, yet near enough to appreciate detail. Even when I was young, I knew I was seeing beauty that could not be matched.

I once caught a ride with an old Eskimo, Mark Palliser. He had a whaleboat with no engine. His power was the wind, or in a calm, the efforts of his old wife and her two sisters on the oars. There was very little wind, but it was with us. We soaked along at a couple miles an hour, vastly content in the warm fall sun. We stopped on convenient little islands to boil a kettle for tea, eat a few of the millions of ripe berries, and check for any sign of bear or caribou. Mark was on a hunting trip but not working very hard at it. The wind was cool, the planks of the boat comfortable in the warm sun.

It was a day when work and hurry were out of mind, the clock forgotten. The three old ladies sat together and muttered away to one another, their eyes missing nothing. Mark sat in the stern, the tiller under his arm, and his black pipe in his mouth. Me? I lay on a pile of nets just out of the wind but well in the sun. I slept, and when I awoke, I watched the hills as we slowly passed them. The colours in the hills were somehow remote and unreachable. Those on the slopes were brilliant and friendly. Every shade of red and yellow you can imagine.

Late in the afternoon, we passed the last of the islands and picked up a breeze from the sea. As we left the narrows, old Mark stood up and stared back at the calm water and glowing colour behind. He said, “Me, I live here all my time, summer and winter. I think the old bay, he more pretty as anything.” Amen, Mark.

27 Father Henry was known to the Netsilik as Kayoaluk (The Red One), because of his red beard, and perhaps for other reasons.