CHAPTER 6

LOW MOOD AND THE ART OF GIVING UP

Pain or suffering of any kind, if long continued, causes depression and lessens the power of action; yet is well adapted to make a creature guard itself against any great or sudden evil.

—Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species, 18871

If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. Then quit. No point in being a damned fool about it.

—Attributed to W. C. Fields

A young man came to our clinic for treatment of moderately severe depression. He had lost interest in most everything, was sleeping poorly and losing weight, and said he was a failure and that his future was hopeless. He attributed his failing grades in community college to his poor sleep and depression. His father was a mason; his mother was a teacher. There was no family history of depression, and he did not have problems with drugs, alcohol, or medical conditions. He easily qualified for a diagnosis of major depression. We started him on an antidepressant and cognitive behavioral therapy.

A month later the psychiatry resident treating him said there was no improvement and asked me to see him again. He said that he was about to be expelled from school but his girlfriend would leave him if that happened. I asked about his girlfriend. He said that she was beautiful and brilliant and he would do anything to stay with her. She was still in high school but would graduate soon. I asked about her future plans. “She’s going to go to this college out east, Vassar, maybe you have heard of it.” “Um, yes, I’ve heard of it.”

What a dilemma! He hated school but had to continue to keep his girlfriend. But he must have known, on some level, that the relationship was unlikely to continue after she left the state for an extremely high-status college. I asked, “What do you think will happen when she moves out east?” He said he had thought about that, and, though it might be difficult, he loved her and was committed to making the relationship work. I said that sometimes it was hard to have a relationship with someone who was far away. He became pensive and said he did not always feel like he fit in with her crowd, but they loved each other. Toward the end of the interview, I asked if he had previously dated other women or if he was thinking of dating other women. He said definitely not.

A few months later the resident asked me to see him again. He was transformed. From a somber, slouching, slow, and soft-speaking disheveled man looking at the floor, he now was enthusiastic and well groomed. He looked me in the eye and said he thought he didn’t need more treatment. We reviewed his symptoms; they were mostly gone. When asked what had happened to make the transformation, he said, “Maybe the drugs worked or something.” However, he had stopped his medications weeks previously. I then asked, “How is school?” “No problem now. I decided to go to work with my dad instead.” “How are things with your girlfriend?” “Great,” he said. “We have lots of fun, it’s really good.” It was now summer, so I asked, “Is she still headed off to Vassar in September?” He replied, “Oh, you mean that girlfriend! She was too uppity. My new girlfriend likes to do all the same kind of things I do. She’s great.”

The Missing Question

Mood disorders pose perhaps the most urgent and frustrating medical problem facing our species. Depression causes more years lived with disability than any other disease.2 Suicide is a leading cause of death, increasing by 24 percent from 1999 through 2014 in the United States.3 Prevention and treatment of heart disease and cancer are increasingly effective, but the rates of depression and suicide have stayed the same or increased, despite decades of intensive research and treatment efforts. Most of the efforts attack depression head-on. They define it, diagnose it, and try to find causes and cures. But the process of revising the DSM diagnosis of depression revealed deep disagreements about a fundamental question: How can pathological depression be distinguished from ordinary low mood?

Jerry Wakefield and his colleagues raised the question with their suggestion that the diagnosis of depression should be excluded not only in the two months after loss of a loved one, as specified in DSM-IV, but also after other equally devastating losses. As noted in chapter 3, the authors of DSM-5 not only failed to adopt the suggestion, they eliminated the exclusion for bereavement.4 So now someone who has five or more depression symptoms for more than two weeks can be diagnosed with major depression even if he or she is in a medical intensive care unit after an auto accident that killed a son or daughter. To most people, that seems ridiculous. Newspapers published impassioned editorials. The blogosphere exploded with opinions. Scientists addressed the problem by studying the differences and similarities among depression, grief, and responses to other losses. However, those studies did little to resolve the debate. Some emphasized the risks of failing to recognize and treat serious depression in the bereaved. Others saw the risk of medicalizing and overtreating ordinary grief. Between these positions is a major gap in our knowledge.

Everyone agrees that some symptoms of depression are normal for a time after a loss. Everyone also agrees that extreme symptoms of depression are obviously abnormal. But disagreement about how to distinguish normal low mood from abnormal depression is intense and enduring. When so many smart people disagree, something is usually missing. What is missing from debates about depression is knowledge about the origins, functions, and regulation of normal low mood.

Trying to understand pathological depression without recognizing the evolutionary origins and utility of normal low mood is like trying to understand chronic pain without recognizing the causes and utility of normal pain. Pain is useful. Physical pain protects against tissue damage. It gets organisms to escape from situations that are damaging tissues and avoid them in the future. Mental pain stops behaviors that are causing social damage or wasting energy. Mental and physical pain can be equally excruciating, even in situations where they are useful. But both are also prone to excess expression when they are not useful, causing chronic pain and pathological depression.

The challenge of deciding if depression symptoms are normal or abnormal is mirrored by the challenge of deciding if physical pain is a product of tissue pathology or an abnormality in the pain system. Pain from a broken leg or a tumor pressing on the spinal cord is obviously normal. However, when no specific cause can be found, doctors consider the possibility that the pain system is abnormal. As a consultation psychiatrist, I was asked to address the question for many medical and surgical patients.

For physical pain, such decisions can be difficult, but finding a tumor or a source of inflammation settles the issue. For mental pain, the challenge is vastly harder because the cause is in the motivational structure of a person’s inner life. Specific life events, such as loss of a loved one, are the closest we can get to a specific cause of pain of the sort that surgeons can find. But ongoing life situations also cause low mood and depression.

When is low mood normal, and when is it abnormal? No amount of knowledge about mood mechanisms can answer the question. An answer requires understanding the origins and adaptive significance of mood. It requires knowing how the capacity for normal mood variation gives selective advantages, the situations in which high and low mood can be useful, and how mood is regulated. It requires recognizing that many mood changes are normal but not useful. This knowledge is the essential but mostly missing foundation for understanding mood disorders and for discovering why mood regulation mechanisms are so vulnerable to failure.

A Few Definitions

Much confusion arises because words describing mood states are used in different ways. Mood usually refers to a long-term pervasive state, akin to climate, while affect is the expression of a current emotional state, more like the weather. However, there is no sharp boundary among mood, affect, and emotion, and the terms mood disorders and affective disorders are used interchangeably. I will use the word mood here to refer to the dimension that ranges from depression to low mood to high mood to mania. The word depression is now so closely associated with pathology that I will use low mood to describe symptoms of mild depression, without any implication of pathology or normality.

High mood is a pleasurable state of enthusiasm, energy, and optimistic activity usually associated with situations where activity is likely to pay off grandly. It is closely related to joy, the short-term pleasure from getting what has been desired, and happiness, the enduring state that can persist if most desires can be satisfied. Low mood is the painful state characterized by demoralization, low energy, pessimism, risk avoidance, and social withdrawal that is aroused by certain situations, especially those in which efforts to reach a goal are failing. Sadness can feel very similar to low mood, but it results from specific losses; it often does not include the pervasive lack of motivation that can characterize low mood and depression. Grief is the special kind of sadness caused by death of a loved one or other major loss. Tomes have been written to distinguish these and other mood states, but because emotions are products of evolution, not design, they overlap in untidy ways that defy exact description.

|

LOW MOOD |

HIGH MOOD |

|

Pessimism |

Optimism |

|

Risk avoidance |

Risk taking |

|

Inhibition |

Initiative |

|

Low energy |

High energy |

|

Social withdrawal |

Social engagement |

|

Quiet |

Talkative |

|

Slow thinking |

Fast thinking |

|

Unimaginative |

Creative |

|

Submissive |

Dominant |

|

Lack of confidence |

Confidence |

|

Low self-esteem |

High self-esteem |

|

Analytic thinking |

Subjective thinking |

|

Expecting criticism |

Expecting praise |

How Can Low Mood Be Useful?

Much confusion about depression results from the human tendency to think that specific things must have specific functions. Things we make, such as spears and baskets, have specific functions. So do parts of the body such as the eye and the thumb. It therefore seems natural to ask “What is the function of low mood?” For emotions, however, that is the wrong question. A better question is “In what situations do low mood and high mood give selective advantages?” However, most ideas about the utility of mood have been framed as possible functions, so we must start there.

One possibility is that even ordinary mood variations are not useful. They could arise from glitches, having as little utility as epileptic seizures or tremors. There are good reasons for thinking that this is incorrect. Syndromes that arise from defects in the body, such as epilepsy or tremor, happen to only some people, but nearly everyone has the capacity for mood. We all have a system that adjusts mood up or down depending on what is happening. Such regulation systems can be shaped only for useful responses. Pain, fever, vomiting, anxiety, and low mood turn on when they are needed. This does not mean that every instance is useful; false alarms can be normal. But it does mean that such systems need to be understood in terms of how and when they are useful.

The London psychoanalyst John Bowlby was one of the first to propose evolutionary functions for low mood. Thanks to conversations with the German ethologist Konrad Lorenz and the English biologist Robert Hinde, he turned an evolutionary eye toward the behaviors of babies separated from their mothers.5 After a short separation, some reconnected with the mother quickly, others acted distant, and a few acted angry. A longer separation led to a reliable sequence: initial wails of protest, followed by silent rocking and huddling in a ball that looks for all the world like an adult in a state of despair.6,7

Bowlby saw that crying motivated mothers to retrieve their infants. He also saw that extended crying would waste energy and attract predators, so if the mother did not return soon, inconspicuous withdrawal would be more useful. These ideas developed into attachment theory,8 which provides the foundation for understanding mother-infant bonding and the pathologies that result when it goes awry. Bowlby deserves recognition as a founder of evolutionary psychiatry for his insight that attachment evolved because it increases the fitness of both mother and baby.

More explicitly evolutionary analyses in recent decades have challenged the idea that only secure attachment is normal. In some situations, babies who use avoidant or anxious attachment styles may motivate their mothers to provide more care.9,10,11 If regular smiling and cooing don’t work, it may work better to scream indefinitely when she leaves or to give her the cold shoulder when she returns.

George Engel, the psychiatrist at the University of Rochester who coined the term biopsychosocial model, proposed a function for depression that is related to attachment. He suggested that a lost young monkey could conserve calories and avoid attracting predators by staying quiet in one place. He called this “conservation-withdrawal,” noted its resemblance to depression, and emphasized the similarity of depression to hibernation.12,13

Aubrey Lewis, a founder of the Institute of Psychiatry in London, believed that depression could signal the need for help.14 The idea was advanced further by David Hamburg, the former chair of psychiatry at Stanford University.15 Some evolutionary psychologists give the idea a cynical twist by suggesting that depression symptoms, and especially suicide threats, are strategies to manipulate others into providing help. Edward Hagen has suggested that postpartum depression is a specific adaptation shaped to blackmail relatives into providing help.16,17 He views the symptoms as a passive threat to abandon the infant and finds support for this view in evidence that postpartum depression is more likely when the husband is unsupportive, resources are scarce, or the baby needs extra care. Depression and suicide threats certainly can be manipulations. However, there is little evidence that depression is a reliable response in most mothers in such situations, and it is not at all clear that those who express more depression get more help from otherwise unhelpful relatives. Also, the theory does not fit well with prior research by psychologist James Coyne showing that depression elicits caring, helpful responses only briefly from relatives; after that they tend to withdraw.18

The Canadian psychologist Denys deCatanzaro suggested the even more disturbing idea that suicide can benefit an individual’s genes.19 If an individual in a harsh environment has little chance of future reproduction, suicide could free up food and resources that relatives could use to have children who would carry some of the individual’s genes into future generations. This would be the ultimate example of selection shaping a trait to benefit genes at the expense of the individual. But the idea, while creative, is almost certainly wrong. Even in harsh environments, suicide is by no means routine. Even sick elderly people who can’t reproduce are often desperate to live longer. Also, why bother killing yourself? Why not just wander off or stop eating?

British psychiatrist John Price recognized an important function of depression symptoms based on his close observations of chickens.20 Chickens that lose a fight and descend in the pecking order withdraw from social engagement and act submissive, thereby reducing further attacks by chickens higher in the hierarchy. Price went on to study the same phenomenon in vervet monkeys.21 They live in small groups containing a few males and a few females. The alpha male, who gets essentially all the matings, has bright blue testicles. Until, that is, he loses a fight with another male. Then he huddles into a ball, rocks, withdraws, and acts depressed as his testicles turn a dusky gray. Price interprets these changes as signals of “involuntary yielding.”22,23 By signaling that he is not a threat, the loser escapes attacks by the new dominant male. Better to yield, and signal yielding, than to be attacked.

Price worked with psychiatrists Leon Sloman and Russell Gardner to apply these ideas in the clinic.24 They observed that many depressive episodes are precipitated by failure to accept a loss in a status competition. They view low mood as a normal response to losing a competition and depression as the result of continuing useless status striving, a situation aptly described as “failure to yield.” Other researchers, especially the British psychologist Paul Gilbert and his colleagues, have developed these ideas further.25 They interpret diverse stressful life events as a loss of status, and they observe that many patients recover when they give up an unwinnable status competition.

The anthropologist John Hartung independently proposed an interesting variation, with the intriguing designation of “deceiving down.” He notes that being subordinate to someone with lesser abilities is a perilous situation. The natural inclination to show one’s stuff will be perceived as a threat, likely resulting in an attack or even expulsion from the group. The solution? Deceive down; that is, deceptively conceal your abilities.26 The best way to do that is to convince yourself that you are less worthy and able than you are, a pattern similar to the neurotic inhibition and self-sabotaging that Freud attributed to castration anxiety.

Further support for the connection between status losses and depression comes from the extraordinary data gathered by the British epidemiologists George Brown and Tirril Harris.27 In their detailed studies of women in north London, they found that 80 percent of the women who developed depression had experienced a recent life event that met their careful definition of “severe.” Of all women who had experienced severe life events, only 22 percent developed depression; however this rate is twenty-two times higher than the 1 percent of women who do not experience such an event. Of the women who had experienced a severe life event, 78 percent did not develop depression during the next year, leading to new studies of “resilience.”28 This careful research provides superb evidence for the role of life events causing depression. Scores of newer studies confirm and extend the role of life events in causing depression.29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37

Some events are much more likely to precipitate depression than others. In the Brown and Harris study, an episode of depression occurred after 75 percent of events characterized by “humiliation or entrapment” but only 20 percent of loss events and 5 percent of danger events.38 These data support Price’s theory nicely, especially if humiliation or entrapment is assumed to involve status conflicts. Describing specific life situations vastly increases predictive power compared to generic measures of life events or “stress.”

The involuntary yielding hypothesis seems correct for many cases of depression I have treated. Myriads of spouses limit their achievements, and even their view of their own abilities, to preserve their marriages. The deceiving-down social strategy prevents attacks by those with more power, at the price of depressive symptoms. An ambitious young lawyer I treated did not use deceiving down; he gave a brilliant presentation that upstaged an ineffective senior partner—who subsequently proved to be very effective at derogating the work of the young upstart, who was soon depressed.

The function of signaling yielding to prevent attack can be reframed in terms of the situation in which it is useful: loss of a status competition. This allows consideration of other ways in which low mood might be useful in that situation: reassessing social strategies, considering possible alternative groups, investing more in selected potential allies, or withdrawing socially until a better time.

Even when reframed as a response to a situation, however, the theory remains specific to one domain—social resources—and one aspect of that domain—social position in a hierarchy. Fighting an unwinnable status contest is one subtype of the more general situation of failing to make progress in the pursuit of any goal. After a status loss, signaling submission stops attacks by those with more power. What about failing in other efforts? Is preventing attacks after a status loss the main function of depression symptoms?

My experience with patients suggests not. Even within the domain of social status, depression symptoms do things other than signaling submission, such as motivating consideration of alternative strategies and new alliances. Also, while about half of my patients with depression seem to be trapped pursuing unreachable goals, many of those goals are not about social position. Is unrequited love a pursuit of a status goal? What about trying to find effective treatment for a child with cancer?

Debate won’t answer such questions; we need data about what events and situations give rise to which symptoms of depression. Billions of dollars have been spent in the search for brain abnormalities in people with depression and millions investigating the role of “stress.” It is a great scientific embarrassment and tragedy that funding agencies have not allocated the resources needed to discover exactly what kinds of life events and situations cause exactly which depression symptoms.39,40,41

Increased thinking about one’s problems is characteristic of low mood. The thinking is often actually rumination. The problem goes around and around in the mind without ever reaching a solution, like a wad of grass that a cow chews, swallows, regurgitates, and chews again. One of my former colleagues, the psychologist Susan Nolen-Hoeksema, viewed rumination as a maladaptive cognitive pattern that is central to depression and best stopped if at all possible.42 In an astounding but tragic bit of luck, she gathered data on depression and tendencies to ruminate just before the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake in California. Interviewing the same subjects again after the earthquake revealed that those who had a tendency to ruminate were more likely to have become depressed, even when other predictors of vulnerability to depression were controlled.43

In a widely discussed 2009 article in Psychological Review, biologist Paul Andrews and psychiatrist J. Anderson Thomson, Jr., proposed nearly the opposite view.44 They argued that rumination helps to solve major life problems. In their view, depression withdraws interest from action and outer life to free up time and mental energy for ruminating to solve the problem. This article extended a related proposal Andrews and biologist Paul Watson had made in a 2002 article, that depression evolved to serve the function of “social navigation.”45 In a firm critique of these ideas, the Newcastle University evolutionary psychologist Daniel Nettle pointed out that there is little evidence that rumination solves social problems, or that depression speeds finding solutions.46 The Norwegian evolutionary clinical psychologist Leif Kennair concurs, and I agree with their critique.47

Nonetheless, social withdrawal and thinking a lot can be useful when one encounters a dead end in life. I greatly admire a 1989 book by the Swedish psychoanalyst Emmy Gut entitled Productive and Unproductive Depression: Its Functions and Failures.48 Using vivid case studies based on historical figures, she argued that depressive withdrawal and intense cogitation can improve coping when major life problems require a major change but can also leave some people stuck in unproductive depression. Major life failures may motivate allocating enormous effort into finding new strategies. However, as Gut, Nettle, Nolen-Hoeksema, and others note, rumination and withdrawal are not reliably optimal responses to such situations.

The functions summarized in the previous paragraphs are some of the most compelling that have been proposed to explain low mood and depression. Framing these functions as alternatives has motivated much useless debate; all may be relevant. However, their significance and relationships to one another become clearer when the frame shifts from their functions to the situations in which they can be useful.

Mood Adjusts to Cope with Changing Propitiousness

Most behavior is in pursuit of a goal. Some efforts are attempts to get something, others to escape or prevent something. Either way, an individual is usually trying to make progress toward some goal. High and low moods are aroused by situations that arise during goal pursuit. What situations? A generic but useful answer is: high and low moods were shaped to cope with propitious and unpropitious situations.49 A propitious situation is a favorable one in which a small investment gives a reliably big payoff. If a herd of mastodons is coming down the valley, exuberant pursuit will likely be worth the effort and risks. If your job is selling new cars, extra effort in a boom year will pay off. In an unpropitious situation, efforts are likely to be wasted. If no mastodons have been sighted for months, expeditions to look for them will likely waste time and energy. Trying to sell cars during an economic downturn is not as fruitless, but it is no fun.

Individuals whose mood rises in propitious situations can take full advantage of opportunities. Individuals whose mood goes down in unpropitious situations can avoid risks and wasted effort and can shift to different strategies or different goals. The capacity to vary mood with changes in propitiousness gives a selective advantage.

The story gets more interesting fast. When times are good and likely to stay that way, there is no need for exuberant effort now. If mastodons come by every day, seeing a herd is no reason to get excited. If your crop can be harvested anytime, relax. But if mastodon sightings are rare, intense effort now will be worth it. It seems paradoxical, but intense high mood is valuable mainly for short-lived opportunities. Low mood is more useful for temporary unpropitious situations than indefinite bad times. People who experience sudden big losses improve with time, but the distortions of depression often make that impossible to see.

Life’s Three Decisions

Making three decisions well is all it takes to maximize fitness. The challenge of picking wild raspberries illustrates how mood helps to make these decisions well. First, how much energy should go into your efforts at the current bush? Should you pick berries as fast as you can or at a leisurely pace? Second, when should you quit? Is it better to keep picking berries from this bush or to stop and look for another one? Finally, when it is time to do something else, what should you do next? Gather another kind of food, do something else, or go home?

Our lives are sequences of such decisions on varying time scales. Should I keep editing this paragraph or move on to the next one? Should I keep writing or take a break for lunch? Should I keep trying to write this book or give up and take up golf? My writing is slowing and my enthusiasm is waning, so now is a good time for lunch.

There, that’s better. A brief break refocuses attention to a slight variation on the central question: Why are people who lack the capacity for mood at a disadvantage? Mood variation does not have to exist. We could go about our days in a steady state, neither enthused by unexpectedly finding a tree laden with ripe fruit nor discouraged by walking for hours to find a tree empty. We would experience neither the excitement at smiling, steady eye contact from the most attractive person in the room nor the deflation upon realizing that the invitation was intended for someone else. Without a capacity for mood, neither winning the lottery nor going bankrupt would influence levels of energy, enthusiasm, risk taking, initiative, or optimism. How best to pick berries offers a model for much else in life, even intensely personal decisions such as deciding whether to continue in a job or a marriage.50

Berry Picking and Mood

If you have ever spent an afternoon picking wild raspberries, you have experienced the emotional changes that guide foraging. Finding a bush laden with ripe fruit arouses a tiny thrill. With joyful enthusiasm, you pull off berries in handfuls, some of which are so delectable they never make it to the bucket. As the bush gets depleted, the berries come more slowly, then slower yet. Enthusiasm wanes. Finally, you are reaching through prickles to try to get that one last deformed berry. Your motivation for picking from this bush is gone, and a good thing, too. It is senseless to try to get every berry from every bush. However, jumping too quickly from bush to bush is also unwise. How long should you stay at each bush to get the most berries per hour? The problem may seem abstract, but making such decisions well is crucial to the fitness of nearly every animal.51

The mathematical behavioral ecologist Eric Charnov came up with an elegant solution, one that illuminates much about mood in everyday life.52 To keep things simple, assume that it always takes the same amount of time to find a new bush (Search Time on the graph). When you find a bush, berries come fast at first, then slower and slower yet; that is why the curved line is steep at first, then slowly levels off. You can stop picking at any time along that curve. The longer you stay, the more berries you get from that bush, but to get the most berries per hour, you need to stop and go looking for the next bush at just the right time.

The best time to stop is at the point that gets you the most berries per hour. The number of berries is the height (the dotted vertical lines), and the time is the width (Search Time plus Picking Time), so you will get the most berries per hour if you stop at the point where the line with the steepest slope (the solid one) just touches the top of the curve. If you leave sooner (the lower dashed line), or stay longer (the higher dashed line), you will get fewer berries in an hour.

The Marginal Value Theorem

Charnov called this the Marginal Value Theorem, because all the action is at that spot “on the margin” where the rate of getting berries at the current bush dips below the number of berries you can get per hour by moving to a new bush. The core idea is simple but profound. You don’t have to do calculus to get the right answer, you just need to follow your emotions. To maximize the number of berries you get in a day, go looking for a new bush whenever you lose interest in the current bush. Thanks to your emotions having been programmed by natural selection, that will generally be the point at which the rate of berries coming from the current bush slows to the average number per minute across many bushes. This decision-making mechanism is built into the brains of nearly every organism. Ladybird beetles, honeybees, lizards, chipmunks, chimpanzees, and humans all make such foraging decisions well. No calculation is needed; motivation flags at the optimal time to make a switch.

The decision about when it is best to quit one kind of activity and do something different follows the same principle. If bushes and berries are so sparse that you are spending more calories each hour wandering about than you are getting from picking berries, the best thing to do is to quit. Even if berries are plentiful, there comes a time when quitting is best, because if you already have a thousand, picking more means lugging a heavy bucket and spending whole days in the kitchen making more jam than you can eat in a year. Well before that point, motivation turns negative and sensible people head home.

The Marginal Value Theorem sets the rhythm of our days. We start an activity with gusto, stay with it awhile, then lose interest and move on to something else. How long we stay depends on the start-up cost, which is equivalent to the cost of finding a new berry bush, how the payoffs decline with time, and the payoffs of available alternatives. To read a book, for instance, you need to find the book, settle into a chair, turn on a light, and start reading. If you jump up to do something else after just a few minutes, you will never read much.

People with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) know this all too well. Their motivation for the current task fades fast, and new opportunities glow brightly, like neon invitations. They shift quickly from one activity to another, rarely getting much accomplished. It would be interesting to study how people with ADHD forage for berries. I bet they quit each bush too quickly. However, staying too long is also unwise. People who persist excessively also deserve a diagnosis: attention surplus disorder.53 Interestingly, drugs used to treat ADHD increase dopamine, the same substance released in the brain in response to rewards. Increasing dopamine may make the brain respond as if more berries are coming per minute from the current bush, encouraging persisting at the current task.

When to Quit All Activity

When to quit all activity and go home—or never to go out in the first place—is a related decision that brings us closer to low mood and depression. The general answer is simple: when you are spending more calories each minute than you can get from any possible activity, it is best to go home and wait for a better time.

Bumblebees gather pollen and nectar every minute on warm summer days. As evening comes, cooler air makes flying more costly, and flowers close and become harder to find. At some point in the gathering dusk, it is best to go home. Bumblebees make this decision superbly.54 Their ancestors who quit too soon or persisted too long got fewer calories per day and so had fewer baby bumblebees. For a rabbit, the principle is the same, although the cost of staying out too long is more dramatic: becoming dinner for a fox. For all species, when the expected costs are greater than benefits for any possible activity, the best thing to do is . . . nothing. Don’t just do something, stand there! Find someplace safe and wait for a better time. This analysis gets us closer to low mood and depression.

Some animals go into a dramatic conservation state nightly. The stripe-faced dunnart is a mouselike Australian marsupial that lives in desolate deserts where food is scarce and temperatures fluctuate widely. It can’t get enough calories in a day to keep its body warm through cold winter nights. So its metabolism slows after dark, dropping its body temperature 20 degrees in a bout of minihibernation.55 Sometimes the best strategy is doing even less than nothing.

Other animals must make life-and-death decisions in which taking big risks is best. In a classic experiment, the behavioral ecologist Thomas Caraco and his colleagues let juncos learn that they could find seeds at two bird feeders. Both gave the same average number of seeds per visit, but one gave a tiny consistent payout every time, while the other gave a payout that varied widely. In ordinary temperatures, the birds preferred the sure-thing low-payout feeder. But when the temperature decreased below the point that made survival through the night unlikely on the calories provided by the consistent but low-payoff feeder, they switched. Instead of freezing to death for certain, they took a risky bet that offered some chance of survival, like otherwise doomed prison camp inmates who run for the fences despite guards with guns.56

Harsh times require difficult high-risk decisions. My grandmother was born in February 1884 on a small island off the coast of Norway. On the day of her christening, her father sighted a swirl of fish offshore. A heaven-sent gift for extra mouths to feed in a lean winter? He and his partner rowed out despite the waves. They hoisted their nets again and again, until the boat was full. Should they persist or go home? The fish were still there, and they might not come back, so the men also filled a spare dinghy, connected to their boat by a chain. The wind rose, the dinghy flipped, the chain could not be cut, and both boats went down. My great-grandmother was helpless onshore, holding her newborn daughter as her husband drowned. Optimism and boldness are often worthwhile, but occasionally they are fatal. The perils of risk-taking in a harsh environment may help to explain why my great-grandfather’s surviving descendants have tendencies to anxiety and pessimism.

Making decisions about foraging or fishing remains central to the lives of many people, but most of us now pursue long-term social goals in complex webs of relationships that confront us with difficult decisions about whether to continue big efforts that may be futile. Some competitions offer huge payoffs for a few winners and years of useless efforts for everyone else. Making it as a professional football player is fabulous, but 999 out of 1,000 who try will fail. The rewards for even successful novelists pale by comparison, but even more people try writing fiction. Career pursuits offer easy examples, but mood also guides more personal goals: trying to lose weight, find a job, get along with a cranky boss or spouse, or cope with everyday life despite crippling arthritis. Progress speeds and slows, and mood rises and falls, as we pursue the projects that make up our lives.

This brings us back to the crucial question posed by the Marginal Value Theorem: When is it best to give up on a major life goal? Early in my career, I always encouraged patients to keep trying, keep trying, don’t let your depression symptoms fool you into thinking you can’t succeed. Often that was good advice. Some applicants get into medical school the fourth time they apply. Some singers land a gig with the Grand Ole Opry after their fifth year in Nashville. But more become increasingly despondent as failure follows failure. Sometimes a five-year engagement turns into marriage. Sometimes staying another year in LA trying to break into film pays off. But not often.

Sober experience combined with my growing evolutionary perspective to encourage respecting the meaning of my patients’ moods. As often as not, their symptoms seemed to arise from a deep recognition that some major life project was never going to work. She was glad he wanted to live with her, but it looks increasingly like he will never agree to get married. The boss is nice now and then and hints at promotions, but nothing will ever come of it. Hopes for cancer cures get aroused, but all treatments so far have failed. He has stayed off booze for two weeks, but a dozen previous vows to stay on the wagon have all ended in binges. Low mood is not always an emanation from a disordered brain; it can be a normal response to pursuing an unreachable goal.

Animal Models

The standard way to tell if a drug will be an effective antidepressant is to see if it makes an animal persist in useless efforts. The Porsolt test measures how long a rat or mouse swims when dropped in a beaker of water.57 Rats on Prozac or another antidepressant swim longer. Because the test works to identify antidepressant drugs, it is the basis of more than four thousand scientific articles, with new ones being published at a rate of one per day. Persisting seems like a good thing, and many of those articles describe cessation of swimming as a sign of low mood or despair. But stopping swimming does not mean giving up and drowning, it just means switching to a different strategy: floating with the nose just out of the water. Rats switch to this strategy at about the right time. Those on drugs that make them swim longer are more likely to get exhausted and drown.58

Learned helplessness is another animal model that presumes persistence is good. The psychologist Martin Seligman put dogs in a box with two compartments separated by a partition. Dogs that received a shock learned quickly to jump to the other side to escape. But dogs previously exposed to shock they could not avoid did not jump over even when they could. This “learned helplessness” is thought to be a good model of depression.59 As is the case for swimming rats, however, the dogs may only look dumb. There are no electrical shocks in the wild, but there are other dogs ready to inflict pain again if necessary to maintain their dominant position.

Other Situations in Which Low Mood Is Useful

I emphasized the situation of pursuing an unreachable goal in my 2000 article “Is Depression an Adaptation?”60 In retrospect, my view was too narrow. Low mood can give advantages in several other situations. Striving for social status often creates unreachable goals, but chronic low mood can also be useful for those stuck in a subordinate position. I saw scores of depressed women who had small children, no job, no relatives nearby, and an abusive husband. We tried hard to get them into a shelter, but few would go, and few returned for continuing treatment. If depression diagnoses were based on causes, “depression in someone who has no way to escape an abusive spouse” would be a common mental disorder.

While the focus has been on social situations, physical situations also influence mood. Three are especially salient: starvation, seasonal weather changes, and infection.

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment conducted on World War II conscientious objector volunteers provided dramatic evidence of emotional changes. All subjects were initially healthy and emotionally stable. They agreed to go on diets that reduced their body weight by 25 percent. By the time they got to that body weight, most were fatigued, depressed, and hopeless, spending most of their days thinking about food.61,62 Such caloric deprivation occurred at times for our ancestors, and it continues in many parts of the world. In such situations, it is wise to avoid vigorous competitive activities.

Lack of sunlight makes many people feel down, and seasonal affective disorder is common. It’s hard to say whether low mood in the gloom is an adaptation or a by-product of other mechanisms, but when activity is likely to be dangerous or unrewarding, low mood will be useful.63,64,65

Have you ever awakened with new symptoms of a cold and felt like there was not much point in doing anything? The syndrome was named sickness behavior by the ethologist Benjamin Hart in the 1980s.66,67 He described its possible evolutionary benefits, including conserving energy to fight infection, and avoiding predators and conflicts when not in top form. Many studies document depression symptoms during infection.68 Especially dramatic are severe cases of depression precipitated by treatment with interferon, a natural chemical that gears up the body’s immune response. Nearly 30 percent of patients receiving interferon treatment for hepatitis C get serious depression symptoms, not just fatigue but also feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness.69 This demonstrates that immune responses can cause clinical depression and suggests that some aspects of low mood may be useful when fighting infection.70

Fatigue and lack of initiative make sense during infection, but why have terrible feelings of guilt and inadequacy? These symptoms could be by-products of a crude system. A related possibility is that some systems that regulate goal pursuit evolved from preexisting systems for coping with infection. Or perhaps infections in ancestral environments caused only fatigue, and full-fledged depression occurs mainly in people with modern immune systems that are hyperactive because of excess nutrition or disrupted microbiomes.

The bottom line is that infection is yet another situation that arouses low mood. This does not mean that all depression is a product of immune systems. However, if natural selection co-opted aspects of the immune system to create the systems that regulate mood, that would help explain the strong association of depression with inflammatory diseases such as atherosclerosis.71,72,73,74

What Good Is High Mood?

High mood has been neglected. It seems so obviously wonderful and useful that its adaptive significance has only recently been studied. It fits nicely as the converse of low mood, a suite of responses useful in propitious situations, especially those likely to be temporary. People whose motivation and energy rev up in response to opportunity get a selective advantage compared to those who simply carry on at the same old rate. High mood includes not just increased energy but also flares of creativity, risk taking, and eagerness to take on new initiatives. As Shakespeare put it, “There is a tide in the affairs of men, which taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.”75

Barbara Fredrickson, a former colleague at the University of Michigan, proposed that the benefits of high mood come from tendencies to “broaden and build.” Her experiments, and those of others who followed her lead, demonstrate that high mood creates a more expansive view of the world and a greater likelihood of taking new initiatives.76 These changes are just the ticket to taking advantages of opportunities. However, framing them as functions leads to neglect of other aspects of positive mood and other subtypes that are useful in different domains. For instance, people newly in love feel spectacularly happy. They’re motivated to do anything and everything for the beloved, actions likely to pay off with a relationship and probably sex and offspring.77 Similarly, in the world of status competition, being newly appointed to a high position is exhilarating, motivating new initiatives and alliances likely to have grand payoffs. It is good to take advantage of such opportunities early, before competition from others grows.

A Model

Physiologists investigate what organs are for by cutting them out and watching what goes wrong. Take out the thyroid gland, and the resulting hypothyroidism reveals what thyroid hormone is good for. But there is no way to excise mood. Research on people who do not experience much emotion (alexithymia) is relevant, but it is unclear if people with alexithymia really lack emotional responses or if they suppress awareness of emotions.78

I created a simple computer model to see if a tendency to variable mood would be a better strategy than just carrying on without mood variations. It opened my eyes to things I had not imagined. The model is a game in which three different strategies compete by making different amounts of investment on each of 100 moves. Each starts with 100 resource units.

The “Moodless” strategy invests 10 units each time. The “Moderate” strategy invests 10 percent of its resources on each turn. The “Moody” strategy invests 15 percent of its resources if the previous move gave a payoff and 5 percent if it gave a loss. The payoff for each move is based on a combination of a random number and the payoff on the previous move, so there is some predictability. The average payoff is 1 percent, but on any move the entire investment could be lost or as much as doubled.

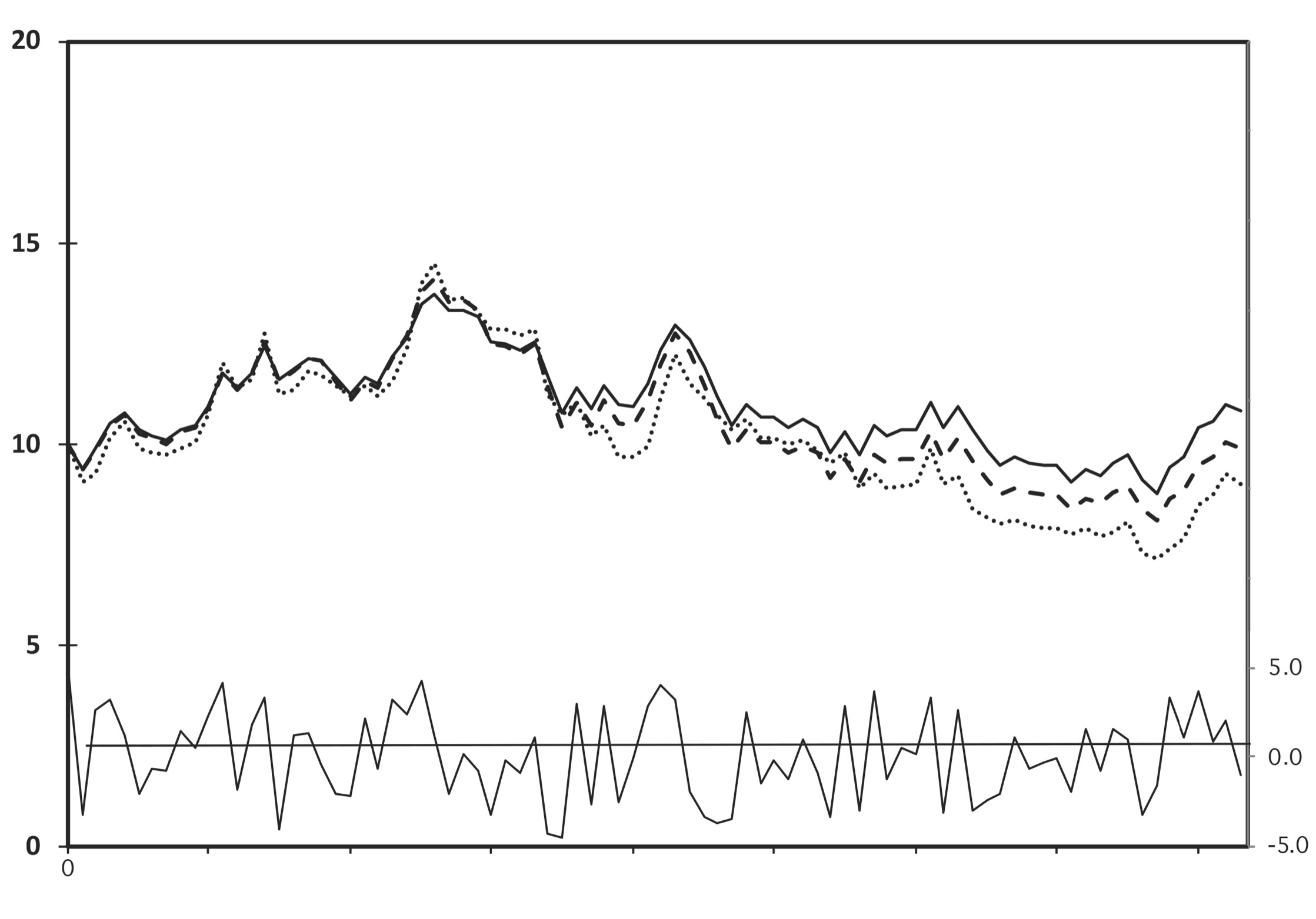

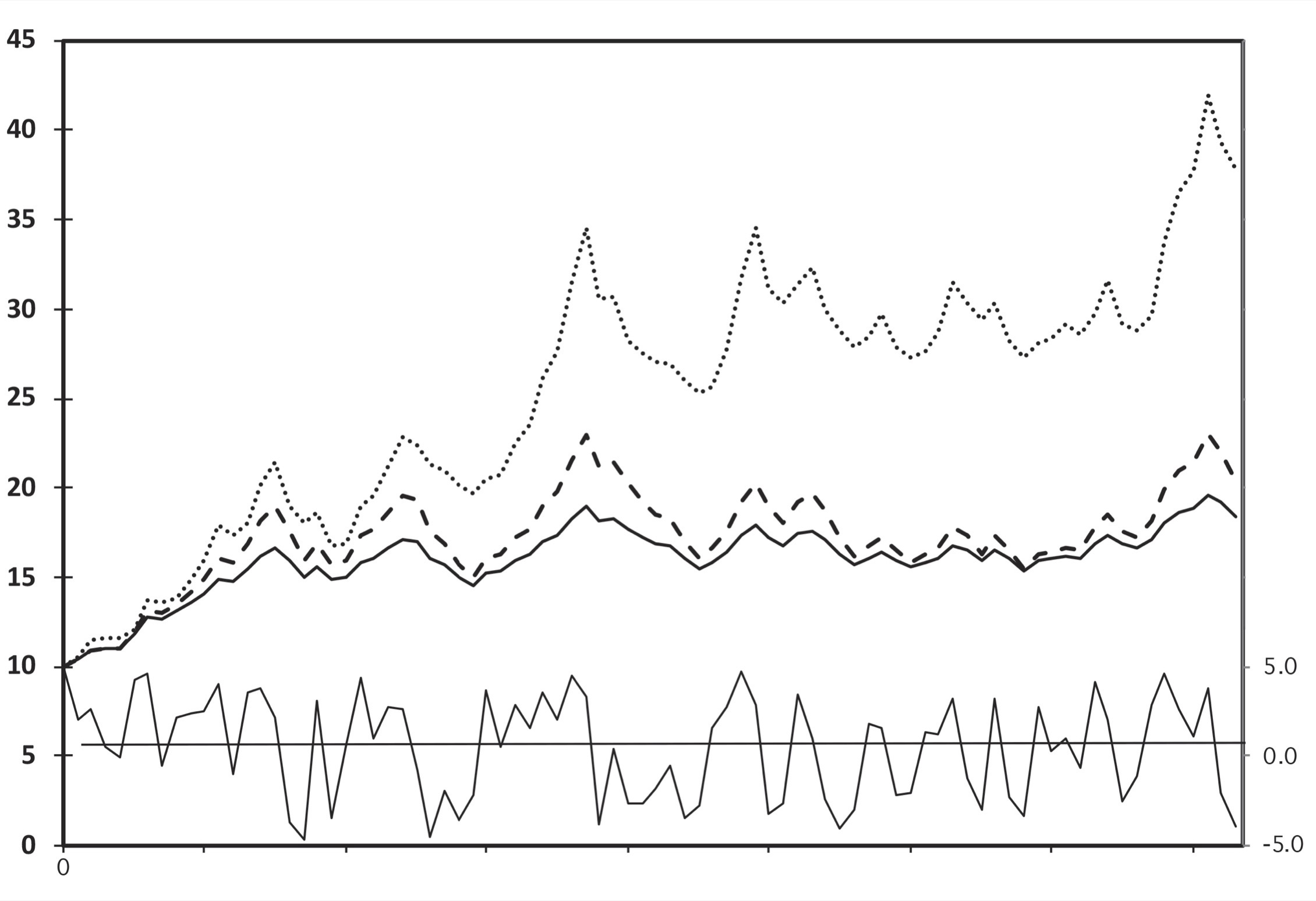

It is great fun watching the game run. One click sets off 100 moves, and four lines crawl across the computer screen, one for each of the three strategies and one to indicate the payoffs at each move. Every run of the game turns out different thanks to tiny variations in the random factors.

Four Runs of the Mood Model

Four runs of the mood model illustrate how chance variations in payoffs result in vastly different outcomes for the three strategies: Moody (dotted), Moderate (dashed), and Moodless (solid). The thin line at the bottom indicates how payoffs vary at each different move in the game.

What strategy wins? It depends on the environment. Usually all three strategies come out about the same. When payoffs are moderately predictable, Moody tends to win because it takes advantage of good times and avoids risk in bad times. As payoffs become less predictable, however, the Moody strategy does worse and worse because it often risks a lot and loses a lot.

Other outcomes were unexpected, just what you hope for from a computer model. The illustration shows the results of running the game four times with identical formulas and starting values. Like the famous hypothetical example of a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil setting off a hurricane in Florida,79 slight variations in the random numbers result in wildly different outcomes. Usually all three strategies give similar results. Sometimes no strategy does very well. When there is a big winner or loser, however, it is usually Moody.

The results from this simple model may help to explain why mood regulation mechanisms vary so much from individual to individual. Minor environmental perturbations can result in drastically different payoffs for different mood regulation mechanisms, even when everything else stays the same. No one system reliably wins; much depends on chance.

When he was a graduate student in my laboratory, Eric Jackson took this much further. He programmed a computer to do 10,000 runs of the game to find out how much mood variability is best. His main conclusion is simple: when rewards vary widely and are somewhat predictable, the optimal strategy is to vary your investments substantially depending on recent payoffs—that is, use the Moody strategy. When rewards are unpredictable, however, more stable strategies win and the Moody strategy goes extinct quickly.

Psychologists Knew It All Along

The idea that mood tracks propitiousness was inspired by my studies of animal foraging, but it is not new. Psychologist friends pointed me to many articles that described the phenomenon in detail. Eric Klinger, a University of Minnesota psychologist, laid out the central ideas especially clearly in 1975.80 When people are making progress toward their main life goals, they feel fine. Obstacles provoke frustration, often observed as anger and aggression. Inability to make progress toward a goal causes demoralization and temporary withdrawal. Prolonged failure of a strategy leads to more severe demoralization and attempts to find alternatives. When extended efforts fail to find a new route to the goal, intense low mood disengages motivation from the goal. When the unreachable goal is truly given up, low mood is replaced by temporary sadness aroused by the loss, and the person moves on to pursue other more reachable goals. Sometimes, however, the goal is something the person cannot give up, such as finding a job or a partner or a cure for a fatal condition. In such a situation, people can get trapped pursuing an unreachable goal, and ordinary low mood escalates into severe depression. Every clinician should read Klinger’s work.

Others have extended these ideas and studied related phenomena. The German psychologist Jutta Heckhausen, now in California, studied a group of childless middle-aged women who were still hoping to have a baby. As they approached menopause, their emotional distress became more and more intense. But after menopause those who gave up their hope for pregnancy lost their depression symptoms.81 The irony is deep: hope is often at the root of depression.

The Canadian psychologist Carsten Wrosch followed up with related studies on parents trying to get help for their children with cancer. The parents who were most set on their goals were more prone to depression.82 Those with a greater ability to shift or give up their goals tended to experience less depression.83

American psychologists Charles Carver and Michael Scheier conducted a series of studies about how the exigencies of goal pursuit influence mood.84 They found that mood is influenced most not by success or failure but by rate of progress toward a goal.85 Faster-than-expected progress bumps mood up, slower-than-expected progress pushes mood down. This is not as obvious as it might seem. Many people think that mood reflects what a person has. This is an illusion, as illustrated by the many rich, healthy, admired people who are nonetheless despondent. People strive to get things, expecting happiness, but it doesn’t work for long. Mood is only modestly influenced by what a person has and only briefly influenced by success or failure. Baseline mood is remarkably stable for most people, and variations reflect mainly the rate of progress toward a goal.86,87

Bad Situations, Low Motivation, and Feeling Bad

When progress toward a major life goal is slowing or stopped, low mood symptoms disengage motivation and induce waiting and considering alternative strategies; then, if no alternative seems viable, giving up on a goal. But is low motivation really the best response in such situations? It avoids wasting energy on fruitless efforts, but if a life strategy is failing, why mope alone in your room? Risk taking and enthusiasm would seem more likely to lead to a successful new strategy. Why don’t life’s reverses shift cognition to an optimistic view of self, the world, and the future to energize a shift to a more useful project?

Sometimes they do. Some people come home after losing a job and quickly realize they have been freed from what would have been decades of drudgery. After a divorce, initial despair is often followed by realizing that better relationships are possible. Even giving up on a failing scientific research project can be exhilarating if it opens new opportunities to conduct more interesting studies. Lines from Tony Hoagland’s poem “Disappointment” capture the moment when “he didn’t get the job,— / or her father died before she told him / that one, most important thing— / and everything got still. . . . You don’t have to pursue anything ever again / It’s over / You’re free.”88

Many benefits of an optimistic view of life are obvious, such as avoiding depression and its associated health risks.89 Compared to pessimists, optimists are half as likely to die of a heart attack.90 Their rose-colored glasses make optimists persist happily without the hesitations that plague others. This can, however, lead to the “Concorde Effect,” the mistake of continuing to sink effort into a hopeless cause. If you walked for hours to get to a hunting place and no game animals show up in the first hour, it is probably worth staying longer but not for days. Making good decisions about when to move on is crucial. Persistence and optimism pay off for most life projects. The costs of finding a new job or partner are huge. Usually it is better just to carry on despite problems, oblivious to possible alternatives, with hopes that things will eventually get better. They usually do.

At some point, however, carrying on is a mistake. If an effort is never likely to succeed, cold-eyed objective assessment becomes necessary. Dozens of studies show that low mood makes people more realistic, a phenomenon called depressive realism.91 People generally are unjustifiably optimistic.92 When asked to press a button to control a light that flashes at random times, most subjects think their presses control the flashes. Depressed subjects, by contrast, soon recognize their helplessness. Depressive realism has been documented in many cultures.93 Using sad stories or films to induce low mood shifts people’s assessments of themselves and the future toward greater accuracy,94,95,96 although the effect may be smaller than once thought.97

When a major life goal is slipping away despite major efforts, low mood dispels optimistic illusions and promotes objective consideration of alternatives. The shift is often painful. I have talked with many patients who thought that their marriages could recover, until a moment when suddenly all hope fell away, as if their rose-colored lenses had suddenly gone dark. However, the lenses of depression are not just gray; they distort reality so people can’t see opportunities that others find obvious. Some unemployed people believe that they will never get another job. Some recently divorced people believe that they are inherently unlovable. Frustrated researchers may believe that their careers are over. What gives?

Pessimism prevents hasty moves. If bad stretches in marriages, jobs, or even writing projects quickly aroused optimism about alternatives, we would move on quickly, oblivious to the costs of starting fresh. Negative views of the self and the future delay big changes, giving time for the original enterprise to bounce back. Sometimes it is best to pull up anchor and move to a different fishing spot, but extra consideration and hesitation are worthwhile if waves or weather make moving risky. The costs and risks of moving to a new city, job, or marriage are larger. I suspect that persistence in failing big life enterprises and accompanying low mood are proportional to the costs and risks of finding something better. But so far as I know, the idea has not been tested.

Finally, as we prepare to shift focus from ordinary low mood to mood disorders, it is worth asking why low mood feels so awful. Why doesn’t the system respond to failing efforts by assessing the alternatives objectively and shifting to the next best one at the right time, without self-doubt, rumination, and psychic pain? Multiple explanations contribute, but I think the main one is the same as the explanation for why physical pain hurts. The suffering that accompanies nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cough, fever, fatigue, pain, anxiety, and low mood motivates escape from a current bad situation and avoidance of future similar situations. Individuals who do not experience physical pain accumulate injuries and usually die by early adulthood. People who don’t feel bad when pursuing unreachable goals spend their lives in contented useless efforts. More low mood might help their genes, but a clinic to boost low mood would be about as popular as a clinic to help people feel more anxious.

Solved?

While attributing specific functions to specific mood states is a mistake, the capacity for mood can be said to have a general function: mood reallocates investments of time, effort, resources, and risk taking to maximize Darwinian fitness in situations of varying propitiousness. High and low moods adjust cognition and behavior to cope with propitious and unpropitious situations.

This global summary makes a large tacit assumption: that mood is one thing. It certainly seems like one thing. We have a word for it, and most people readily recognize descriptions of low and high mood. But do the various parts of low and high mood always come together in consistent packages? Do enthusiasm, risk taking, fast thinking, and optimism always arise in synchrony? Does low self-esteem always come along with pessimism, fearfulness, and low energy?

The different aspects of low mood arise together in the same way as the different symptoms of a cold. They are closely associated but in patterns that differ depending on the specifics of the problem. Matthew Keller took on the risky project of looking to see if different kinds of problems aroused different depression symptoms. Three different studies confirmed his hypothesis. In particular, loss of a partner aroused crying, emotional pain, and a desire for social support, while a failing effort caused pessimism, fatigue, and lack of ability to experience pleasure.98 Another former student, Eiko Fried, took this to the next level with a series of studies showing that the common practice of measuring depression severity by summing up the number and intensity of symptoms tosses out the most interesting and important variations. Analyzing individual symptoms may provide data that help demonstrate the effectiveness of antidepressant drugs and help find the brain mechanisms that go awry in serious depression.99

Relieving Mental Pain

Finally, a caution about a common but dangerous bit of illogic. On learning that low mood can be useful, some people conclude that it therefore should not be treated. This mistake is like the one that arose when anesthesia was first invented: some doctors refused to use it, even during surgery, because, they said, pain is normal. We must not let new understanding of the utility of low mood interfere with our efforts to relieve mental pain.

People come for treatment because they are suffering. Whether pain is physical or mental, finding and eliminating the cause provides the best solution. Sometimes low mood should be respected as normal and useful to help adjust a person’s motivation and life directions. However, often the situation can’t be changed. The loss of a friend, continuing abuse, inability to get a job, trying every night to help a child get off drugs, finding no relief from chronic pain—those are good reasons, but the resulting bad feelings are harmful even if they are normal. In other situations, low mood can be normal and useful for a person’s genes but harmful for the person. Sometimes it is normal but useless in the specific instance because of the Smoke Detector Principle. Sometimes it is normal but useless because we live in social environments so different from those we evolved in. And sometimes low mood is caused by abnormalities in the mood regulation system. Considering all the possibilities allows clinicians and patients to take the same medical approach to low mood that they would for physical pain. Try to find the cause and fix it, but always do what you can to relieve suffering.