The original St. Stanislaus Kostka Catholic Church, shown here, was the first church for Polish-speaking immigrants. This structure proved to be too small and was expanded in the 1880s. Bay County Historical Museum.

Chapter 2

THE POLISH WAR

It was Ash Wednesday 1896.

The lumber boom that had enriched the entire region was waning but still alive, and huge numbers of men were needed in all sorts of industries fueled by lumber. A large number of lumber mills remained in operation, with a variety of manufacturing plants, shipyards, shipping companies, railroads, construction companies and all sorts of service industries that required workers, the cheaper the better, meaning immigrant labor.

After the Civil War through the 1870s, a wave of Polish immigrants arrived in Bay County and most settled in what was called Portsmouth, a village adjacent to Bay City. It was centered on Twenty-second Street, which became Kosciuszko Avenue. The early Polish arrivals were Catholic and needed to attend church services. Most went to St. James Catholic Church on Columbus Avenue, which was considered the Irish church. At one point, there were so many Polish attending services that a Polish-speaking priest was assigned there. Still, the Poles wanted their own parish, and they got one: St. Stanislaus Kostka.

In 1875, a new church was constructed on Kosciuszko. The wood-frame building afforded the communicants services with sermons in their own language by a Polish pastor. It was expanded under the second pastor, Father Augustine Sklarzyk to make room for even more families.

The original St. Stanislaus Kostka Catholic Church, shown here, was the first church for Polish-speaking immigrants. This structure proved to be too small and was expanded in the 1880s. Bay County Historical Museum.

The third pastor, also Polish, was Father Marion Matkowski, who was a take-charge individual. When the wood-frame building became too small again for the growing congregation, a fund drive that included tithing donations from each family and annual pew rents for maintenance raised enough money to build a new church.

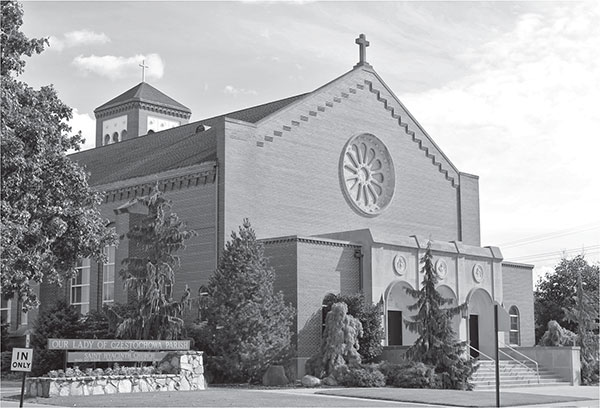

The European-looking Gothic structure was completed in 1892 with Father Matkowski credited as the driving force in getting the new church constructed, and it still is one of the finest-looking churches in Michigan.

Also in the early 1890s, a second wave of Polish immigrants arrived in large numbers, settling in the South End, and began to attend St. Stanislaus. More Polish nuns were assigned to teach the increasing number of youngsters in St. Stanislaus Catholic School.

A rift developed since the older, established wave had become Americanized by speaking English and had become comfortable in the community, taking part in government and civic groups. They resented the intrusion of the new wave of immigrants, especially those who had not paid anything to build the new church and now wanted to take advantage of it without being obligated.

The new church had been opened for only a few days when a disastrous fire erupted along the riverfront in one of the lumberyards, and a firestorm roared through the South End, driven by gale-force winds. The story goes that while hundreds of families abandoned their homes fleeing with as much as they could carry in the wake of the fire, Father Matkowski donned his surplice, filled a bucket with holy water and headed toward the wall of flames. When he got to it, he sprinkled the holy water on the blaze, said a prayer and threw in blessed salt. Witnesses claimed that at once the wind died down, and by evening, the fire was under control.

In the early 1890s, parishioners paid for a beautiful European Gothic–style church that quickly became the epicenter of the “Polish War.” Tim Younkman.

Whether entirely accurate or not, that was Father Matkowski’s reputation in the community, but on Ash Wednesday, February 19, 1896, that would change, kindling a different kind of firestorm.

The priest’s rectory was next to the church, and Matkowski and his assistants employed a housekeeper, Francesca Mickiewicz, and her helper, a pretty fourteen-year-old newcomer by the name of Marta Cwiklinski.

The next day, an assistant pastor, Father Turski, and the father of Marta, Valentine Cwiklinski, confronted Matkowski with an accusation that he had molested the girl. They insisted that he resign his position and allow Turski to take over as pastor. Instead, Matkowski relieved Turski of his duties and said he would inform the bishop in Grand Rapids of his actions. Turski countered that he would go to the bishop and demand that Matkowski, along with his housekeeper, be removed.

While all this was going on, the general public was unaware of the nature of the problem, although rumors circulated quickly that there was a terrible rift between Matkowski and Turski.

Father Marion Matkowski, who had been a widely respected pastor, was falsely accused of molesting a fourteen-year-old immigrant girl. St. Stanislaus Catholic Church.

However, in St. Stanislaus church circles, people became aware of the accusations. Some were astounded that anyone would make such an accusation against a priest, but others believed it and were very angry. Sides were drawn almost exclusively along the newcomer immigrants versus established immigrants. It wasn’t until April that any details of a problem surfaced in the newspapers. On April 27, the Bay City Times-Press reported to a shocked community that St. Stanislaus was to be closed.

The night before, a large gathering of newcomers who backed Mr. Cwiklinski and Father Turski met at Andrejewski’s Hall, the second-floor room above Adam S. Andrejewski’s saloon at 1029 South Madison Avenue. Turski said he had gone to Bishop Henry Richter and made his complaint but was sent back to St. Stanislaus, where he claimed the atmosphere was so bad that he couldn’t stand it. He wanted a committee to see the bishop to demand Matkowski’s removal. They referred to themselves as Anti-Matkowskis—or Antis, for short.

A committee of Antis, headed by Bay City alderman Adelbert Kabat, went to the rectory and talked with Matkowski. Afterward, the pastor announced he would leave St. Stanislaus immediately. He said he was not willing to keep putting up with complaints and demonstrations against him, and announced the school and church both would be closed in his absence until the bishop made a decision. Despite the story in the paper, the general public still didn’t know the real cause for his leaving.

The paper printed a letter the next day from Father C.J. Votypka, who had been the assistant pastor for four years. He praised Matkowski and said criticism by Turski of the pastor was “humbug.” He also referred to the housekeeper, Francesca Mickiewicz, as “a lady and a Christian.”

On May 2, Bishop Richter, accompanied by Matkowski, arrived by train from Grand Rapids and was taken to St. Boniface Catholic Church and the offices of its pastor, Father John G. Wyss. There he met with a church committee from St. Stanislaus, but the details of that session were not disclosed.

The following day, Richter conducted confirmation services at St. Boniface and then at St. Joseph. He ordered all churches in the area to announce that Father Turski and all of those who back him and were opposed to Father Matkowski were “suspended” from the church. That drew the ire of the Antis, who gathered in the schoolyard to demonstrate their anger, threatening to take their appeal to Cardinal Francesco Satolli, the apostolic delegate in Washington, D.C.

Richter said he believed the congregation was misled by Turski and ordered the church and school to remain closed until further notice. Lost in all this seems to be the fact that the public still didn’t know that Matkowski had been accused of molesting the servant girl.

One of the Anti leaders, Frank Ososki, at a mass rally in Andrejewski’s Hall on May 7, claimed that the workingmen of the parish had paid good money for the church and were frustrated that they could not have a pastor of their choosing.

“We will be satisfied with any priest but Matkowski,” he said.

Alderman Kabat surprised the crowd by saying he had led a delegation to see the Bay County prosecuting attorney Isaac A. Gilbert about having Matkowski arrested. Gilbert refused to seek a warrant but said he would talk to the bishop about the situation. The issue was taken out of his hands by other circumstances.

Matkowski was arrested on May 14, and it was the first time the public was informed of the nature of the crime. The warrant was signed by police justice William M. Kelley on a complaint by Valentine Cwiklinski that his daughter Marta was molested on Ash Wednesday evening by Father Matkowski in the parsonage where the girl was employed.

To avoid problems with crowds, Matkowski was arrested by Detective Benson in the offices of Matkowski’s lawyer. Kelley also arraigned him in the law offices rather than have him taken to the police station. Bond was fixed at $1,000, which was posted by the attorneys, and Matkowski was allowed to go to the St. James rectory.

A two-day hearing in police court began on May 26 with Marta Cwiklinski testifying through an interpreter that what she had said about being molested by the priest was true, claiming she was called up to his room at 11:00 p.m. on Ash Wednesday. She said she stayed the night.

Matkowski testified that none of that happened; he had never asked her to come to his room, nor did she come to the room. He said he had no contact with her.

A friend of Marta’s, sixteen-year-old Kate McNamara, a parishioner of St. James, said she was told by Marta that she had made up the story because her father put her up to it.

This was the first time that it was publicly revealed by the defense that the story of child molestation was fabricated, and it was clear to many that Valentine Cwiklinski may have been influenced by Turski. It also was beginning to become clear that Turski had mental problems.

A surprising news item appeared on May 27: Turski was no longer a Roman Catholic priest but had joined, as a priest, the breakaway Independent Catholic Church in Buffalo, New York. The church was not affiliated with Rome.

Housekeeper Mickiewicz testified that on the Thursday after Ash Wednesday, Marta left the house (meaning her place of employment) in the afternoon and did not give a reason for leaving. The housekeeper said she then hired another girl, Jennie Okon, sixteen.

Okon was called as a witness and said that on March 2, Father Turski did not come down from his room for dinner and Father Matkowski told her to take some food up to him. She said Turski let her in his room and asked her to make the bed for him. He asked where Marta was, and she said Marta no longer worked at the rectory. She began to make the bed.

She said: “He blowed out the candle and closed the door, and caught me around the neck. He asked me if Marta was around here. I said no. He said, ‘You be my Marta.’ I broke away and ran down stairs and told the housekeeper.”

She was afraid to tell Father Matkowski what happened, but the housekeeper continued to insist that she at least must tell her parents, which she did a short time before the hearing.

On June 4, Matkowski walked out of the police court a free man at 2:30 p.m.

Justice Kelley said it was his opinion at first that the Matkowski case should be tried before a jury, but after talking with the prosecutor, it became clear that the prosecutor would not continue with the case based on the evidence. Kelley said it was the prosecutor’s opinion that Marta Cwiklinski’s story was completely fabricated and that she and her family were under the influence of Turski, whom he described as “a bad man.”

Matkowski attempted to get some of his papers from the rectory but was shocked to find it occupied by Antis who refused him admittance. The priest had two armed guards with him but chose to retreat rather than cause problems.

On June 18, it was reported that Turski has been advised (by persons unknown) to become a Protestant and to get married. He supposedly retorted that it was good advice, but he had no money. In order to get married, he asked his old friends back in Bay City to help him in his cash crisis. It was only a month earlier that he had joined the new independent Catholics in Buffalo. With this new, radical life change, his behavior had become even more bizarre.

He returned to Bay City, staying in the Fraser House, a hotel on Center Avenue, after lodging a few days with a friend, presumably an Anti, at the extreme south end of Michigan Avenue.

Meanwhile, armed Antis continued to occupy the church property, much to the chagrin of the Matkowski supporters. More trouble had been brewing, and menacing crowds milled around the perimeter of the property.

Bishop Richter arrived in Bay City on June 23 and planned to get a court order reclaiming the property in the name of the church that would allow authorities to arrest trespassers. There was some general apprehension in the community on June 26, when it was reported that an Anti-led Polish militia was being organized in the area surrounding St. Stanislaus and points south. Sheriff Alexander Sutherland toured the South End and witnessed the militia drilling. The leaders of the militia claimed they were practicing for the Fourth of July celebration.

The first real blood of the Polish War was spilled in the wake of the tragic death of Joseph Wiznerowicz, who fell from a tramway and was killed. As Wiznerowicz was a St. Stanislaus communicant, the funeral had to be held in St. James where Father Matkowski held services since St. Stanislaus Church was closed.

On June 28, 1896, the funeral service was packed with Polish people on both sides of the feud, including two women who were neighbors living a block apart on Twenty-fourth and Twenty-fifth Streets. As the service concluded, Mrs. John Naperalski said her neighbor began to abuse her because she was an Anti and should not attend a mass conducted by Matkowski, whom she disliked. The neighbor, Mrs. John Szezodrowski, struck the other woman in the arm. Mrs. Szezodrowski claimed that Mrs. Naperalski talked, whispered and laughed during the services, and she took her to task for it. She said Mrs. Naperalski hit her.

They were separated and were on their way home with their husbands when another confrontation developed, and this time, the men got involved. John Szezodrowski threatened to shoot Mrs. Naperalski “in the stomach.” John Naperalski, twenty-five, got in front of his wife and into the other man’s face, and Szezodrowski shoved him. Naperalski struck the other man, knocking him down into a ditch, and proceeded to beat him. When Naperalski finished hitting him, he got up, and that’s when Szezodrowski pulled out a .22-caliber revolver, aimed at the man’s chest and fired. Naperalski turned to run and was struck in the back by a second shot. However, because he was wearing a heavy coat, neither bullet entered his body, though they did cause severe bruising. At that point, Naperalski’s father appeared, and Szezodrowski shot him, hitting him in the leg.

The two injured men got to their house on Twenty-fifth Street, and Dr. Newkirk was summoned to attend to them. Meanwhile, police officers went to Szezodrowski’s house and arrested him. Szezodrowski claimed he fired his gun in self-defense.

Groups of people from both sides began milling around Twenty-third at Grant and at Van Buren Streets. There was talk that the Pros should get guns and kill off the Antis, and the Antis were heard to say they ought to get a rope and lynch Matkowski if they saw him.

At 7:30 p.m., there were three hundred men around George Kabat’s hardware store on Van Buren and Eighteenth Streets. Meanwhile, the Pros were holding a meeting in St. James School with Matkowski in attendance. A youth acting as a scout ran in to say that a large gang of men was approaching the school and that he heard them say they were going to “wipe the place off the face of the earth.”

Father Rafter of St. James quickly escorted Matkowski to the St. James rectory and sent for police, and a group of armed Irishmen from the parish arrived to help defend the property. Captain William Simmons and a squad of officers with the police wagon arrived, all armed with revolvers and clubs. They found an immense crowd around the school building, including women and children, and Simmons worried that if a riot developed a lot of people were going to be hurt.

Some men in the Antis claimed to have talked to Marta Cwiklinski and said that she had denied recanting her story. She insisted that it was true. The crowd was sufficiently whipped into a frenzy, all aimed at Matkowski. As they moved around the school, the officers jumped down from the wagon and formed a line, guns drawn. The crowd stopped moving. Simmons ordered the lights in the school to be extinguished to show there was no meeting going on. After a few more tense moments, the Anti leaders decided not to have a showdown, and the crowd dispersed.

The next morning, Szezodrowski, the man involved in the shooting, was released on bail pending a hearing.

An injunction was ordered by the Bay County Circuit Court against the Antis, which stated they were forbidden from conspiring to remove Matkowski or from interfering with his duties; plus, they were prohibited from occupying the church property.

In case the restraining orders were violated, the guilty parties were subject to arrest for contempt of court, and the sheriff served notice in English and Polish on each of seventy-six defendants listed. Once the papers were served on all of the parties, Matkowski attempted to re-open the church that Sunday, but the Antis vowed violence.

An Anti rally ensued with five hundred men who claimed the injunction wouldn’t stop the majority from going on the church grounds or into the church itself. There were threats of arson, which prompted Sheriff Sutherland to order deputies to stand guard at the church.

Because of threats of the Antis, Matkowski declined to open the church on Sunday, July 12. Demonstrators who were prepared to disrupt the services melted away, but a large contingent of women, all armed with clubs, stones and pepper (powder), were stationed to prevent Matkowski from gaining entrance to the rectory, where the parish books were kept. There were new allegations by the Antis that Matkowski had embezzled money and that the proof of it was in the parish account books.

The sheriff’s guards were withdrawn from the property, and Antis took over. A man identified as John Bakowski jumped over the fence on July 13 and declared himself to be the duly authorized guard sent by Richter and Matkowski. Moments later, he was attacked, beaten and stabbed in the hand before being thrown back over the fence and off the property.

Insurance companies reported that vandals had plugged the keyholes of fire alarm boxes around the church, which prevented any alarm of a fire. Insurance totaling $31,000 on the St. Stanislaus church was rescinded by the carrier. Fire officials declared that the fire alarm boxes near the church were to be examined each hour by firemen to make sure they were not disabled.

Meanwhile, Bishop Richter ordered Father Turski to go to the Trappist monastery in Gethsemane, Kentucky. It never was clear if he obeyed the order.

On July 22, Bishop Richter ordered Matkowski to remain as pastor and to retake his church. However, Matkowski did not reopen the church but continued celebrating Mass at St. James until August 14, when he announced he was leaving the city until the tensions died down. Two weeks later, he was granted an indefinite leave of absence from his duties and traveled to Europe. Meanwhile, the bishop ordered a young priest, a Father Lewandowski, to St. James in Bay City to assist in the Polish services.

Pope Leo XIII took an interest in the unrest and rioting in St. Stanislaus parish and dispatched an envoy to investigate. Library of Congress.

The troubles at St. Stanislaus had reached the Vatican, and on September 10, Pope Leo XIII, who had taken an interest in what was happening in Bay City, authorized a representative, Father Peter Wawrzerniak, to investigate. He made a house-to-house visit and learned that all the Poles wanted hostilities stopped and the church reopened with a new priest in charge.

A new pastor was appointed, and Father Anthony Bogacki arrived from his former post in Posen, in Presque Isle County, and reopened St. Stanislaus for services on October 4. Bells announcing services rang again at St. Stanislaus on that Sunday without opposition from any faction. The euphoria was short-lived because Bogacki pronounced that all of the Antis must do public penance before being given absolution for their sins, which meant the souls of those Antis who would die without absolution for their sins were doomed to eternal damnation in hell.

That sparked a firestorm. More than seven hundred Antis (now Anti Bogackis) packed into Andrejewski’s Hall to hear from a committee that had met with the bishop about this new priest. They decided to take a wait-andsee attitude for another week.

On October 24, the sheriff was called to the rectory to break up a crowd that had gathered. A committee had wanted to meet with Bogacki, but the priest would not meet with it. It was upset at the heavy penance the priest imposed.

The tensions boiled again on November 13 at the funeral service for Macj Szafranski, fifty-one, who lived on Madison Avenue between Fifteenth and Sixteenth Streets and was employed as a stave piler at William Peter’s sawmill. He had died two days earlier, and it was generally known that he had been an Anti. The funeral cortege left the home and marched to the church for the 8:30 a.m. Mass. A number of those in attendance belonged to the St. Joseph Polish Benevolent Society, wearing their regalia, which included a black velvet sash worn over the shoulder and a silver cross on the front.

When the funeral procession reached the church, Bogacki met them, sprinkled holy water on the coffin and led the procession into the church. Once inside, he asked that the St. Joseph Society members remove their regalia. They refused and said they were a benevolent society, which was to give the widow $600 after the burial. Bogacki said there would be no service unless the regalia was removed and left the church for the rectory.

Outraged, the family left the church to return home, leaving poor Mr. Szafranski in his coffin in the church. Six members of the society stayed with the body along with about one hundred men and women, members of the Anti group. The society rotated six-man committees to hold vigil alongside the casket until such time as Bogacki performed the funeral mass, but he steadfastly refused to perform the service. He said the St. Joseph society could remove the body to St. Patrick’s Cemetery to be buried there in consecrated ground without any further ceremony. Undertaker Frank Wasieleski, 107 Washington Avenue, was asked by police to remove the body from the church for health and sanitary reasons.

The funeral incident caused several businessmen sympathetic to the Antis to purchase land for a new cemetery since the Antis complained they didn’t want to be buried in the “Irish” St. Patrick’s Cemetery. When Bogacki heard of this new cemetery land, located near Green Ridge cemetery on what is now Columbus Avenue, he was upset, declaring that the bishop would never consecrate this new burial ground. During High Mass on November 22, Bogacki allegedly called the Antis “hogs” and “wild Indians,” which angered many, and a large portion of those communicants got up and left the church, joining an even larger mob milling around outside the church. They blocked the doors so the priest could not leave to go to his rectory, and the police were called by Pro-Bogacki men. When officers arrived, they found more than one thousand men and women blocking entrances to the church and keeping the priest a virtual prisoner. More police arrived and made their way into the church to talk to Bogacki.

The crowd grew more menacing, and the police decided to force a way through the crowd to the priest’s residence, about thirty feet from the church door. They did not draw their guns but had their nightsticks ready. The Pro-Bogacki force also was armed, mainly with clubs but some had firearms. Then all hell broke loose.

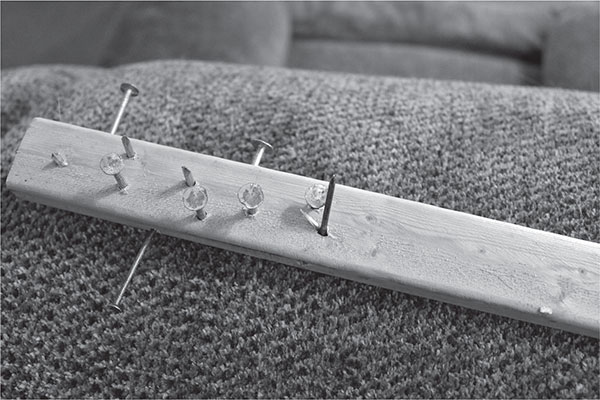

The armed Antis forced the Pros off the church grounds, beating many in the head and face as they chased them. Some of the men had knives and some women had rocks while others were armed with nail-laced clubs called nail bats. Many people were seriously injured. The Antis retreated to the home of Matthew Janowicz, 915 South Farragut Street. Once again, Dr. Newkirk was summoned and tended to the wounded, most suffering head wounds. Other people who were injured to a lesser degree went to their own homes and family members treated them.

During this mêlée, Joseph Stichanski, a Pro-Bogacki man, who was guarding the priest’s house, pulled his revolver and aimed at the crowd. Police officer Andrew Wyman shoved him back into the house. Had Stichanski fired the weapon, he would have been attacked mercilessly and possibly killed by the frenzied crowd.

Meanwhile, police officers were guarding Bogacki inside a small room in the church. Reinforcements were requested by officers with a plan to get the priest out of the area of St. Stanislaus and over to St. James, nine blocks to the north.

Police chief Murphy was informed that the Antis had picked a group of men to go into the church and take Bogacki out to the street. They also vowed to get into the rectory and take the parish books, which were being guarded by Stichanski, who still was armed.

One of the weapons of choice was a potentially lethal club like this one, known as a nail bat. Women especially favored it because it was easy to wield. Tim Younkman.

The handful of police knew they couldn’t hold out against a mob of over one thousand, so Captain Simmons negotiated a deal in which the priest and Stichanski would be allowed to leave the property unharmed. A hack pulled up, and Bogacki was able to escape the mob, being driven to the Rouech House, a hotel at 100 Fifth Avenue, a block from the police station. Stichanski walked away from the rectory and was not harmed.

Mayor Hamilton M. Wright arrived at the church to meet with Antis leader Frank Wasieleski, informing him that violence was against the law and, if it continued, he would have to act. He urged the Antis to protest peaceably because violence hurt the image of their cause.

The Antis allowed a cook into the rectory without incident, and they deserted the church premises. However, hours later, various informants told police and city council members that an attack on the parsonage was scheduled for dawn, possibly to bomb the residence. The mayor ordered all members of the police force to be ready at dawn in full gear and heavily armed, but day dawned without any violence, although some minor vandalism, such as rocks thrown through windows, continued.

Police arrested three men in connection with earlier rioting in which Andrew Biskupski was badly injured when struck in the head. The three men arrested were Valentine Kropski, Andon Foustyn and even seventyone-year-old Michael Torkowski. The latter two were convicted in police court and fined fifteen dollars each after it was revealed that both men had clubs and both delivered blows with them to the victim’s head repeatedly. Kropski was discharged without a conviction.

Warrants were sworn out for three other men in the riot. They were John Yachimovich, Kropski (again) and Joseph Beys, all for assault and battery. The trial of John Yachimovich ended in a hung jury on December 14, and a new trial was ordered. Action on the others was delayed.

The Polish War reached down into the ranks of the elementary school students when two eleven-year-old boys, Bernard Dumbroski and Frank Skrypzak, quarreled on the school grounds during recess on December 14, and Skrypzak used a jackknife to stab the other boy under the right shoulder. Dumbroski, of 812 Michigan Avenue, ran home and showed the wound to his mother, and she treated him. His father was enraged and went to the police, who promised to investigate.

Tensions were raised again when Bogacki announced that at the beginning of the New Year, all those who declined to pay pew rent had to vacate their pews. The Antis said they would be willing to pay the rent but would not do so until the backers of Bogacki were removed from authority on church committees.

New Year 1897 brought even more trouble when one of the Antis— Zenar Wroubleski, forty-two, the father of six, living on the corner of Fremont and Lincoln Streets in the South End—died of typhoid fever on January 2. He also was a member of the St. Michael Benevolent Society, which provided $600 to the widow and $50 toward the burial of a member. The society was on good terms with the parish, with a banner kept inside the church, but Bogacki refused to give Wroubleski spiritual consolation prior to and declined to bless the body after his death.

Instead of providing a funeral Mass, he closed the church doors and refused to have anything to do with the funeral. Bogacki said the sick man had refused last rites, which apparently was true. When the funeral cortege arrived at the church, it found the doors locked, and moments later, a wagonload of police, along with the mayor, arrived. The St. Michael’s society members wanted their banner from inside the church returned to them and said that they would proceed to the new Polish burial ground, which they dubbed St. Stanislaus Cemetery. The mayor secured the banner for them, and the crowd moved off in the direction of the cemetery, where the burial took place, even though the grounds had not been consecrated.

The war was about to escalate, and the story became a front-page headline, unusual for local news stories. This one in the Tuesday, January 5, 1897 edition of the Bay City Times-Press proclaimed: “Riot. The Poles Had One Today.”

On that frigid morning, a committee elected by the Antis led a crowd of about five hundred men and women and went on the church grounds to confront Father Bogacki, ordering him to leave the parish for good. Special police officer James Fitzgerald, assigned as a bodyguard for the priest, would not let them into the parsonage. Someone used a club to smash a plate glass window in the door, and Fitzgerald drew his revolver and fired.

This sparked a barrage of missiles from the crowd—clubs, rocks, bricks and other objects were thrown through the rectory windows. The crowd surrounded the house and continued throwing things until every window and door was smashed to pieces. They tore the shutters from the windows, ripped doors from the hinges. Several shots were fired from the crowd at the house, and officers inside returned fire.

Several deputies on duty went to the windows and pumped bullets into the crowd, striking several of the Antis as they tried to run away. As the Antis retreated, Joseph Bartkowiak stood in the yard and was hit in the chest by a bullet. The mob stopped and turned around when Bartkowiak fell and surged toward the house, gaining entrance and smashing all the furniture. They demanded the lives of Father Bogacki and any men inside who were protecting him. Ink from a desk was taken and spilled onto the carpet, bookcases were smashed and a kitchen pantry was destroyed, the contents spilled onto the floor. A wheelbarrow was rammed through the kitchen door.

Bogacki, Fitzgerald and other deputies and several parishioners were on the second floor, all armed and ready for the final rush of the Antis. By now nearly every member of the mob had a weapon, and many had guns.

Police chief Murphy was informed of the riot and was told that at least a dozen men had been shot. He ordered all of the police officers and special officers to get their guns and nightsticks, loaded them in the police wagon and headed for the church grounds.

The Pros, mostly women, had organized into a mob on one side of the church grounds and had armed themselves with clubs, or nail bats, which also were the weapons of choice for the women on the Anti side.

By January 1897, the violence had escalated, as reflected in this Bay City Tribune news story. Bay City Tribune, January 6, 1897.

As the wagon approached, the crowd surged to surround it. At that moment, two civilians jumped from the house window and tried to make a run for it, but the mob caught one of them, identified as Joe Stachinski, and began beating him unmercifully. Police sprang from the wagon and went to his aid, preventing the crowd from killing him. Three officers picked him up and carried him to the patrol wagon, unconscious but alive.

Another man, Alexander Yonkowjak, tried to escape from the house and was caught, beaten and rescued by police, who also managed to take one of the Antis into custody. Chief Murphy, seeing that there were upward of one thousand people in the mob, decided to negotiate. He said he would get Bogacki out of the house but the Antis had to agree not to attack him, to which they assented. Meanwhile, Fitzgerald had exited the back door of the house and was chased by members of the mob, who caught up to him and began beating him with clubs as he ran. He suffered head injuries but kept upright and was saved by a group of Pros who had a wagon, pulling him aboard and away from the crowd.

Because Fitzgerald was involved in the shooting, he was taken into custody by Murphy, and officers arrested Andrew Deska, one of the men who struck Fitzgerald.

The police led Bogacki out of the house and up Grant Street toward St. James rectory. He was not attacked by the crowd, although at least five hundred people followed him, shouting insults and threats.

Police said Frank Novakowski, of 908 South Michigan Avenue, was struck in the leg by a bullet fired from the house. He managed to get to his home, where a doctor was summoned. The bullet smashed a bone in his knee, and a piece of bone had to be removed along with the bullet.

Casmir Wisniewski, of 720 South Van Buren Street, had been one of the Pros guarding the priest inside the house, and when he emerged from the building, he was shot in the arm and clubbed with boards as he tried to escape. The bullet struck him in the right arm below the elbow.

Mrs. Joseph Turkowski, of South Michigan Avenue, was in the churchyard and was struck by a bullet through her leg. She limped home and was treated there by a doctor.

It also was reported that members of the crowd had gone into the basement, where a large amount of wine and liquor was stored. They handed out the bottles through a basement window to their friends, so some members of the crowd, at least, were fired up with alcohol on top of their religious zeal.

By 5:00 p.m., the riot had quieted, although a large number of Antis continued to hold the grounds. Meanwhile, fire chief Thomas K. Harding issued orders that all of his firemen should be armed in case they were called out for a blaze connected to the riot.

That night, Officer Fitzgerald was arraigned in police court on a complaint by Joseph Bartkowiak, charging him with assault with intent to do great bodily harm less than murder. An examination was scheduled for January 9, and bond was set at $800. Meanwhile, another warrant was issued against Bogacki for firing a pistol, the shot wounding Bartkowiak, and Andrew Deska, charged with assaulting Fitzgerald, was released for lack of evidence. Stephen Nowaski, charged with assaulting Alexander Yonkowjak, was released on $200 bail pending the trial, also on January 9.

The Antis appealed to the Papal Legate in Washington, D.C., but Archbishop (later Cardinal) Sebastian Martinelli upheld the church position against them. Library of Congress.

The Antis then appealed again to the apostolic delegate, this time Archbishop (later Cardinal) Sebastian Martinelli.

On January 12, the Pro-Bogacki faction held a mass meeting at the new Washington Hall, on the corner of Washington and Eighth (now McKinley) Streets. The group was led by Alderman Augustus Elias. Two of the Antis tried to gain entry but were turned away by two guards. The meeting was called by leaders to advise all the Pros to continue to obey the law despite the provocations by the other side. The significance is that the Pros were becoming more organized by several respected leaders.

A police court jury found Stephen Nowicki guilty of assaulting Alexander Yonkoviak, whose head was struck repeatedly with a nail-laden club. Nowicki was ordered to pay a fine of thirteen dollars and court costs of eight dollars or serve forty days in jail. He planned to appeal, he said.

By January 13, Bishop Richter had seen enough and ordered St. Stanislaus School closed. The teaching nuns were ordered to pack their things and head by train for Detroit, and a detachment of armed policemen escorted them for their protection all the way to the railroad station. The sudden move left about five hundred children without a school, which was too large a number for the public schools to absorb all at once. It wasn’t known at the time if other Catholic schools would accept them, or how much the parents would have to pay if they were allowed to attend.

At another mass meeting of the Pros at Washington Hall on January 17, the highlight of the night was the reading of a letter from Bishop Richter ruling on the appeal by the Antis about all of the church problems and the right to have benevolent societies associated with the church. Richter said his ruling was sent to Archbishop Martinelli in Washington, D.C., and that the new Papal Legate agreed with his decisions.

He disposed of the first charge that the church committees overseeing the budget were incompetent and misappropriated funds. The bishop said three of the five leaders of the Antis had been on those committees that had approved the handling of the church finances.

Bishop Richter also dismissed arguments that Father Bogacki used abusive language from the pulpit. The bishop noted the priest should not have used improper language but said it was the pastor’s duty to “to inveigh against vice and to endeavor to suppress disorders in the parish.”

Regarding charges that societies have been unjustly treated, the bishop pointed to the decree from the Fourth Provincial Council of Cincinnati regarding rights and duties of Catholic societies, which meant their formation and bylaws had to be approved by the bishop, the members had to be Catholic and their children were to attend a Catholic school: “Societies already approved remain approved and enjoy the privileges of Catholic societies as long as they remain faithful to their constitution and observe the laws and rules regulating such societies.”

Richter pointed out that anyone in rebellion against the church authority could not receive the sacraments. He said some of the dissenters had presumed to lay down rules and guidelines for the priests, but that was the jurisdiction of the priests’ superiors only.

He said a two-member committee, men who were not already on committees or on the parish council, would examine the church finances and would audit accounts each year.

On January 31, another Pro-Bogacki meeting was held in which it was announced that children readying for their first communion would be welcome at St. Boniface Catholic Church. It also was reported that delinquent pew rental fees at St. Stanislaus totaled $10,403, listing the names of those who owed the fees.

A possible violation of the U.S. Constitution developed on February 6 when the Pros obtained an injunction against two more Antis preventing them from going onto the church property. They were William V. Prybeski, publisher of the Polish weekly newspaper Prawda , and Adelbert Kabat, an Eighth Ward alderman. These appeared to be violations of the First Amendment freedom of the press rights and of interfering with an elected city official performing his duties in representing his constituents.

The next day, another injunction was issued against the editor of the Polish newspaper, identified only as Laskowski. He went to the circuit judge Andrew C. Maxwell to find out how such an injunction could be issued in violation of the First Amendment. Maxwell said he had no knowledge of it since it was done by Bogacki’s lawyers and held no validity.

A mass meeting of the Antis gathered on February 20 at Andrejewski’s Hall and listened to the reading of a letter written to the church committee by Archbishop Martinelli. It stated that those who had caused the disturbances and caused trouble for the pastors of St. Stanislaus could not be considered Catholics until they ceased and desisted from their rebellious acts and that they had to accept the rulings and decisions of Bishop Richter. Despite the threat of excommunication, the Antis continued their defiant rhetoric.

Two men who were found guilty in Bay County Circuit Court of violating the restraining order were sentenced by Judge Maxwell. Charles Glaza was fined $250 and sentenced to six months in jail, and John Swiontek was fined $50 and sentenced to thirty days in jail.

On March 1, Judge Maxwell announced how fed up he was about the criminal activities associated with the St. Stanislaus feud. He said he had heard testimony in the injunction case by Alderman Kabat that the Antis were going to put guards on the premises day and night in shifts because they claimed a right to be there. Maxwell termed the action as “a conspiracy against the injunction of the court which is still in force, and I propose to put a stop to it.”

He ruled that the sheriff would be put in charge of the property as a receiver and that he would proceed to serve attachments on all parties assuming any right to hold possession of the premises in violation of the injunction.

Sheriff Henry Guntermann took control of the church property at 7:00 a.m. on March 2, 1897. He summoned a number of deputies to assist in relieving the Anti guards who were on the property although they agreed to depart peacefully.

Meanwhile, Judge Maxwell ordered three more Antis to jail for contempt of court in violating the injunction. They were W. George Kabat, forty-seven, proprietor of the hardware store on the corner of Van Buren and Eighteenth Streets; Ignatz Buzalski, fifty-three, of 721 South Farragut Street; and Bruno Chudzinski, twenty-nine, of the South End. These three were identified as leaders of the Anti movement.

By 9:00 a.m., about four hundred men and women gathered around outside the grounds of the church property. The women were verbally abusive to the sheriff’s men and even showed them nail bats they had under their shawls. The crowd thinned out after several hours, although the sheriff, sensing that trouble was brewing, asked Deputy Kinney to go downtown and gather up more deputies. The sheriff’s men held the property all day and into the night without any major incident. He left four Polish deputies in charge overnight, and all four were Pro-Bogacki members.

However, the Antis were on the march again, this time attacking businesses and residences. On March 14, between 9:00 p.m. and midnight, eight houses and other property occupied by Pro-Bogacki people were attacked. Windows were smashed and property damaged.

Thomas Gilenecki, owner of a saloon and a grocery in a large double store on the corner of Michigan Avenue and Twenty-sixth Street, was one of the victims. A large crowd gathered outside his place armed with clubs and began breaking all the windows and smashing the shades.

The crowd moved on to Twenty-sixth and Monroe Streets and hit the house of Joseph Stachinski, who was one of the victims in the January 5 riot. Angry Antis smashed the windows of his home. The other victims included Joseph Linda, Frank Lange (a brick thrown through a window barely missed one of his young children), Joseph Dukarski’s saloon (Twenty-second and Monroe Streets) with a door smashed in, Roch Andrzejewski’s grocery (Twenty-second and Monroe) with a damaged front and Joseph Kusmisch (windows broken on his house on South Jackson near Twenty-second).

The crowd attacked the home of John Zaremba, the church organist, where someone broke a window with a fist, leaving a blood trail.

Bogacki announced on March 29 that he had resigned from St. Stanislaus and had met with the bishop regarding the situation. With the church closed, the parishioners continued to attend Mass at various local Catholic churches. Some ventured across the river to West Bay City and the German Catholic church on Seventh and Raymond Streets. That is the area near today’s Holy Trinity Catholic Church on Wenona Avenue.

Another bizarre twist came on June 6, 1897, when the German Catholic Church caught fire. Alarms sounded at 12:30 a.m., when a sawmill worker on his way home spotted the blaze. The fire soon burned through to the roof, which collapsed at about 1:15 a.m. The church had been built four years earlier, with the second floor used for worship and the ground floor for a school. A news account quoted a young Polish man who said a number of Antis had been attending the services there and noted that the congregation was not pleased and had made its displeasure clear. There were remarks about it in the Polish newspaper.

Officials said the fire was set with incendiaries. Antis denied having anything to do with it and blamed it on the Germans, who didn’t like the fact that Bishop Richter had made arrangements for Poles to attend the church.

Meanwhile, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled that George Kabat was to be set free and was not guilty of contempt of court based on the evidence, although it stated the injunction was valid and other convictions were legal.

For the next few months throughout the summer, there were occasional problems, some skirmishes back and forth, but no major rioting occurred.

It would be another year before the bishop agreed to reopen St. Stanislaus with a new pastor and a promise from leaders of both factions to adhere to a truce to make the parish work again and to reopen the school for their children.

It is interesting to note that the official church history referred to this whole conflict as “an internal parish problem” and “a misunderstanding.” It did record that Father Matkowski left the parish and went to Grand Rapids, where he was instrumental in building a new church, St. Isadore. The history also lists Bogacki as his successor, noting “his tenure as pastor was brief.” It states the bishop ordered the parish closed until June 18, 1898, when he named Father Joseph A. Lewandowski as administrator and Father Anthony Bieniawski as his assistant.

The parish history continued: “The difficult situation was far from settled; however, Fr. Lewandowski managed to serve the spiritual needs of the parishioners. It remained for his successor to eventually bind up the wounds of discontent and division and to reunite the parishioners.”

That cleric was Father Edward Kozlowski, who was appointed pastor on January 6, 1900. One of his goals was to unite the parish through building a new, bigger school, which opened in 1910.

However, there was a burning desire of many parishioners to form their own parish so they could officially split from St. Stanislaus with the blessing of the church. The ill feelings continued to foment under the surface, but no one seemed willing to return to the campaign of the previous violence. The agitation for a new parish grew.

Some local historians adhere to the idea that the creation of a new parish was just due to the natural increased membership of St. Stanislaus and that overcrowding was a problem. That part was true as far as it goes, but the ill will between the factions was undeniable. It was clear that if a new parish was approved, the Antis would be attending the new one even if it meant moving within its boundaries. The same was true with the Pros, who would move across boundary lines to get back into the St. Stanislaus parish.

Father Edward Kozlowski was appointed pastor to obtain a truce and eventually restored order. St. Stanislaus Catholic Church.

Petitions were sent up the ladder to Rome, and studies were authorized to determine if a new parish was feasible. Since many of the Antis lived in the deeper South End, from the river to the townships, all below Twentyseventh Street, the new parish was created in 1906 with a boundary at Twenty-seventh Street, and a church was built at the corner of Cass and Michigan Avenues. St. Hyacinth Catholic Church, named after a twelfthcentury Polish martyr, opened in 1907, exactly ten years after the battles of the Polish War.

The attitudes between members of St. Hyacinth and St. Stanislaus continue to this day, although they will tell you they don’t know why. They just know they don’t like those in the other parish.

One of the results of the Polish War was the creation of a new parish, St. Hyacinth, at Michigan and Cass Avenues. Tim Younkman.

In an ironic twist, the recent cost-saving consolidation of parishes by the diocese has merged St. Stanislaus and St. Hyacinth parishes under the new name of Our Lady of Czestokowa, referring to the iconic Black Madonna painting that is housed in that Polish city.

Perhaps the reunification of parishes will create the final chapter of Bay City’s Polish War, one of peace and reconciliation.