Chapter Ten

Shadows

(1881–1882)

As the new decade opened, the financial downturn that had begun in the mid-1870s continued to worsen, not only in France but throughout Europe. Many forces and factors were at work, but France was especially hard-hit by competition from foreign agricultural products as well as by natural disasters that decimated the country’s all-important vineyards. French agricultural incomes plunged, leaving impoverished farmers and their families with little alternative but to migrate to urban centers such as Paris, where they swelled the numbers of the unemployed.

In response, France’s new republican government came up with a gigantic public works program for railways, roads, and canals—a popular but hugely expensive undertaking. The government also reintroduced the tariff—an unpopular measure, as it contributed to a rise in food prices. With poverty and discontent festering, the government entered into the international race for empire—with the intent of enhancing French prestige as well as diverting discontent at home. In the spring of 1881, France began to extend its influence into North Africa (Tunis), and would soon be looking toward Southeast Asia. Georges Clemenceau, who strongly opposed colonial expansion, took the measure of the current leadership and launched an attack on his longtime political enemy Jules Ferry, who now was prime minister of France.

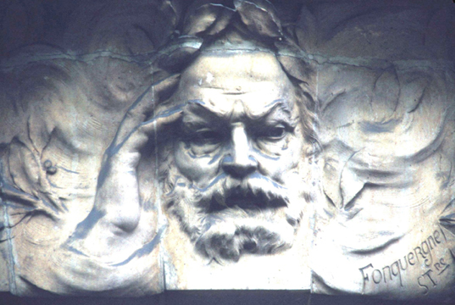

Bas-relief of Victor Hugo (Marcel Fonquergne), 124 Avenue Victor-Hugo, Paris. © J. McAuliffe.

Their enmity dated from the siege of Paris, when Ferry—as prefect of the Seine—supported Thiers’ decision to seize the cannon at Montmartre, despite Clemenceau’s efforts to negotiate a peaceful resolution to the confrontation. Ferry regarded Clemenceau as a rabble-rouser, while Clemenceau considered Ferry a secret conservative bent on undermining the Republic. Ferry’s education policies did not go far enough for Clemenceau, and his colonial policies went too far. Clemenceau was not the only one to be outraged by Ferry’s tactics on the Tunis affair. The whole business had a murky look, and many members of Parliament were angered at being ill informed and then required to ratify the entire affair after the fact.

As a result, although the republicans continued to be securely in charge of the Third Republic, it remained a question as to which faction of republicans would lead the government in the months and years to come. As the elections of 1881 approached, anyone with a finger in politics could foresee that the so-called Opportunists—the current republican leaders of the Third Republic—faced some bumpy times ahead.

* * *

Several years before, Victor Hugo had unexpectedly come face-to-face with death. In actuality, it was an encounter with old age—an experience that, even at seventy-six, he had not anticipated. Mercifully, the stroke he suffered was a mild one, but for a time it looked as if it would bench him permanently. His flood of poetry stopped flowing, and his amorous adventures came to an abrupt halt.

As it turned out, the indomitable old man recovered; sheer determination and willpower did the trick. He no longer was a one-man torrent of words, but in other respects he seemed to have regained his lease on life. Still, his brush with mortality had alarmed a number of prominent people, who decided that it was time to pay him tribute before it was too late. After all, he was the Third Republic’s most visible symbol.

And so, in February 1881, the Third Republic gave him a blowout party to celebrate his eightieth birthday. In actuality, February 26, 1881, marked Victor Hugo’s seventy-ninth birthday, but that made no difference to those who were determined to do him honor. He was, in official parlance, “entering his eightieth year,” and that was enough to justify whatever festivities the Republic could summon up.

And the festivities were indeed overwhelming. They began the day before Hugo’s birthday, with presentations and honors and a triumphal arch erected at the entrance to the street (Avenue d’Eylau, 16th) where he lived. Schoolchildren were absolved of their misdeeds, and crowds began to pour into Paris for the occasion. On the morning of the great day, an enormous and well-organized procession stretched from the Avenue d’Eylau (now the Avenue Victor-Hugo) down the Champs-Elysées to the center of Paris. At noon, the procession set off in a flurry of snow, with senators and deputies leading the way. Five thousand musicians followed, playing the Marseillaise. Clubs, schools, and whole towns marched past the old man and his two grandchildren (the remainder of his descendants, as both of Hugo’s sons and his elder daughter were now dead, and the second daughter, Adèle, was insane). In all, it took six hours for the procession of half a million people to pay their respects.

It was a magnificent event, and Hugo—who had never been overburdened with modesty—rose to the occasion, presiding over the endless stream of admirers like the icon he had in fact become.

* * *

Despite opposition the previous year from Paris’s city council, Sacré-Coeur continued to go up—and down. In April 1881, with the basilica’s massive support system well under way, Cardinal Guibert celebrated the first Mass there, in the crypt.

In the meantime, Gustave Eiffel was completing the internal framework of Sacré-Coeur’s secular rival, the Statue of Liberty, while at the same time building the great hall of the Paris office of Crédit Lyonnais. The Impressionists were busy as well, holding their sixth exhibit—with Monet and Renoir again abstaining.

This was the year that Monet moved from Vétheuil to Poissy, on the western outskirts of Paris. Despite an improvement in his finances, he had not paid the rent in Vétheuil for more than a year, and an irate landlady seems to have prompted the move. He brought Madame Hoschedé and her six children (plus his own two) with him, but he was displeased with the new location and spent the remainder of the winter on the Channel coast, reveling in the scenery and the solitude. When he finally returned, he once again was inundated with the concerns of a family with eight children—including financial responsibility for them all (Ernest Hoschedé had refused to pay for his children’s and wife’s share for some time, and probably was unable to do so). Monet soon bolted once again for the coast, this time taking Madame Hoschedé and the children with him.

Pissarro, with six children of his own, lived in similarly chaotic conditions. In a wintertime letter to his oldest son, Lucien, he reported that the children had taken sick, but were now almost recovered, “and the usual racket is beginning again.”1 Renoir’s life was far less turbulent, as his Luncheon of the Boating Party so ravishingly testifies.

Despite the Impressionists’ general preference for out-of-doors paintings that were, by necessity, painted quickly, Renoir began this work during the summer of 1880 and completed it many months later in his studio. (Even Monet revised and put “finishing touches” [his words] on many of his paintings in his studio, and after a visit to Renoir’s studio, Berthe Morisot commented in her notebook that “it would be interesting to show all these preparatory studies for a painting, to the public, which generally imagines that the Impressionists work in a very casual way.”)2 Still, like his fellow Impressionists, Renoir continued to reject the formalism of the reigning school of academic painting, with its careful renditions of historic tableaux. Instead, he wanted to capture real life. This meant a focus on the mundane, from country roads to domestic pleasures. It also meant a new attention to ordinary people as they went about their everyday lives.

A decade earlier, at the Grenouillère, Renoir and Monet had captured not only the effect of light on water, but also the palpable pleasure of Parisians holidaying on the Seine. Renoir again caught this relaxed and festive mood with the casual conviviality of his Luncheon of the Boating Party—a moment of sun-drenched bliss on the balcony of the Maison Fournaise, in Chatou.

Like the Grenouillère, the Maison Fournaise—which Renoir called “the most beautiful spot in all the environs of Paris”—owed its existence to the railroad, which since the 1830s had provided easy access to this delightful area just west of Paris. Boating on the Seine, as well as strolling along its banks, soon became a major leisure activity for Parisians of all classes, who democratically mixed and mingled there. Sensing good business possibilities, a bargeman and boat builder by the name of Alphonse Fournaise built an open-air café and small hotel on the Ile de Chatou. With the help of his daughter, Alphonsine, and his son, Alphonse, he also developed a boat rental business. Soon his enterprise, the Maison Fournaise, became a meeting place for writers, artists, and celebrities of all sorts, including Guy de Maupassant, who described it in 1881 in La femme de Paul, calling it the restaurant Grillon.

The summer afternoon depicted in Renoir’s charmed scene at the Maison Fournaise stands in marked contrast with Manet’s miserable summer of 1881, which he spent in Versailles. Unfortunately the summer was rainy and gloomy, and his health continued to deteriorate. “I don’t need a chair,” he remarked irritably on one occasion, upon being offered one. “I’m not a cripple.”3 But it was obvious to all around him that he was getting worse and worse.

Yet at heart he still was the same charming bon vivant who took a keen delight in his friendships. These included the American painter James McNeill Whistler, then in London, to whom Manet introduced his friend, the collector Théodore Duret. Manet also continued to adore the entire process of painting and drawing, although it was becoming more and more taxing for him. “You’re not a painter unless you love painting more than anything else,” he remarked to a friend during these difficult months. “And a grasp of technique is not enough, there has to be an emotional impulse.”4

Manet, of course, was not and never had been lacking in either emotional impulse or technique, but his genius had consistently gone unrecognized during much of his career. It was only now that he began to receive some long-overdue signs of respect from the conservative art establishment. Earlier that year, in a change of plans, he had sent Henri Rochefort’s portrait rather than the painting of Rochefort’s sea escape to the 1881 Salon. This turned out to be a good decision, for despite the jury’s antipathy to Rochefort’s (and Manet’s) politics, it at long last awarded Manet a medal.

Recognition came on another front as well. That autumn, after the Opportunists encountered an overwhelmingly pro-Gambetta electorate, Jules Ferry’s cabinet reluctantly resigned and Gambetta at last came to power. Gambetta’s tenure would be brief (lasting only from November 1881 to the following January), but long enough for Antonin Proust, Manet’s friend since boyhood, to become Gambetta’s minister of fine arts. Proust immediately saw to it that Manet was made a chevalier in the Legion of Honor—delighting Manet, but also leaving him a bit despondent. Earlier recognition “would have made my fortune,” he wrote one well-wisher, but “now it’s too late to compensate for twenty lost years.”5

* * *

Manet was not the only artist whom Antonin Proust helped during his brief tenure as minister of fine arts. Proust also gave a significant boost to Rodin’s career by acquiring for the nation Rodin’s most important bronze to date, St. John the Baptist.

Unlike Manet, Rodin was still at a point where such official recognition could and did make a huge difference. This acquisition, together with the state’s earlier purchase of The Bronze Age, gave him a nice push along the road to fame and fortune. Unlike Manet, Rodin had a reticent manner and an indifference to politics that made it unlikely that he would offend any of the political figures who could and did help him along the way. Indeed, as Champigneulle points out, Rodin “had the knack of spotting people who could be useful to him.”6

This was fortunate, because Rodin shared with Manet a fierce commitment to his own artistic vision, despite the controversy that it inevitably ignited. Rodin unhesitatingly challenged conventions, especially those of the academic sculptors whose insipid creations he abhorred. But once past the controversy over The Bronze Age, this did him little real damage, since he increasingly circulated among and cultivated some of the most important members of Parisian society—people with money, taste, and connections. Once won over, these patrons provided invaluable support while this indomitable sculptor continued to shock the more staid members of the art world.

Quite unlike Rodin or Manet in temperament was Degas, who by this time had justifiably earned his reputation as a devastating wit. Holding forth at the Nouvelle-Athènes (at Place Pigalle), which had replaced the Café Guerbois as the most popular meeting place for artists, Degas regularly used his well-honed observations and aphorisms to demolish his colleagues. According to the writer and poet Paul Valéry, Degas was “scintillating” and “unendurable,” a ruthless raconteur who “scattered wit, gaiety, terror.”7 Edmond de Goncourt agreed, but in typical Goncourt fashion seemed to relish Degas in full attack mode. In 1881, following a dinner with mutual friends, Goncourt wrote that “it was fascinating to watch that hypocrite eating his friends’ dinner and at the same time . . . plunging a thousand pins into the heart of the man whose hospitality he was enjoying—all this with the most malevolent skill imaginable.”8

It was perhaps Degas’ way of striking back at a world that had so unexpectedly removed his status as a gentleman artist, forcing him to support himself. He could never adjust to this change in status, and he found it especially difficult to finish anything that had been commissioned and paid for in advance—a transaction that, in his view, lowered the work in question to the level of a commodity. The uncertainty of the economy only worsened his predicament. Although a growing number of collectors were buying from him, he complained of financial hardship. Despite his complaints, he probably was far better off than he indicated. Still, the unpredictability of the economy was an unsettling and very real presence throughout France during these years.

* * *

The boost that the government’s public works program gave the economy was real but temporary, lasting only until early 1882, when it dramatically collapsed in the wake of the high-flying merchant bank, the Union Générale.

A recent (1878) addition to the French banking scene, the Union Générale originated as a business venture for the Catholic political right, including monarchists and members of the Catholic hierarchy. With the Catholic Church in France on the defensive and secularism on the rise, Eugène Bontoux (a practicing Catholic) had seen need and opportunity converging in such a venture, which he believed would by its very existence challenge the current banking structure. As its appeal unabashedly stated, the bank’s purpose was “to unite the financial strength of Catholics, . . . which [now] is entirely in the hands of adversaries of their faith and their interests.”9 These adversaries, as another statement made clear, were Jews and Protestants.

Bontoux, a former engineer, had held responsible positions with the Rothschilds’ French and Austrian railroads, ultimately as director of the Südbahn, the major Austrian line. In these jobs he had proved himself to be a capable manager, but at the helm of the Union Générale he enthusiastically joined in the reckless speculation of the times. Thinking big, he aimed at making the Union Générale the largest financial institution in the nation, and inflated his capital accordingly.

At first, Union Générale’s success was gratifyingly stratospheric, and its stock soared. But the times were more than usually volatile, and in January 1882, the stock market plunged, taking Union Générale with it. The disaster impacted nationwide, wiping out the life savings of the well-to-do as well as tradespeople, artisans, domestic servants, and farm laborers. Long lines of people waited all day outside the Union Générale offices in the hope of regaining something—but to no avail. According to Le Figaro, “The despair of these people who have lost everything is pitiable to contemplate. Numbers of priests were among them, and many women, weeping bitterly.”10

The crash reverberated throughout the country, setting off a malaise that went especially deep among the working classes, who blamed the government for this and subsequent financial disasters. But this malaise contained a deeper and more malignant strain, which placed the blame on Jewish bankers, whom irate investors claimed had plotted to destroy the Union Générale. Bontoux, who was sentenced to five years in prison and fled to Spain to avoid serving his sentence, eventually returned and wrote a book in which he, too, blamed the Jews (as well as the Freemasons) for the Union Générale’s demise.

In fact, the Rothschilds and other bankers had advanced funds to Bontoux during the panic, in an attempt to prevent the market crash that followed. But this was not what a significant number of people throughout France wanted to believe. Threatened by the incomprehensibility as well as the power of the financial system that had ruined them, they looked for scapegoats and found them among the people who for centuries had been relegated to handling money. It was perhaps not surprising that, especially during hard times, this malignant weed of anti-Semitism would reappear and multiply.