Chapter Twenty-One

Between Storms

(1894)

By 1894, the Panama affair had run its course, sweeping away political careers and contributing to growing cynicism on the part of a badly burned and disillusioned public. Clemenceau was not the only politician to go down in defeat in 1893; some 190 new deputies entered the Chamber after the elections. These new members, as well as a large number of the old, were careful to distance themselves from the Opportunist government under which the scandal had bloomed. Calling themselves Progressives, they appealed to a moderate-to-conservative swath of the electorate by advocating tariffs, opposing a progressive income tax, and signaling a willingness to ally with non-royalist Catholics against the radical left.

These moderate and conservative republicans harbored a deep fear of socialism, which was starting to make significant headway as a political force, thanks in large part to episodes of police and army violence against striking workers. But even more feared than the socialists were the anarchists, who rejected political action altogether in favor of militancy. A series of bombs had gone off in 1892, decimating the homes of a judge and prosecuting attorney. These two men had dealt savagely with workers whose May Day demonstration ended in bloodshed, after mounted police charged in. The bomb-thrower went to the guillotine, but his fate only stirred up further animosity among his anarchist colleagues, who proclaimed him a martyr and a hero. Not long after, a bomb was delivered to the Paris office of a mining company whose workers were on strike, killing five policemen. Parisians were panic-stricken.

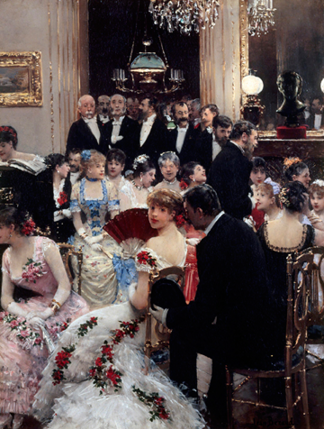

La soirée, ou autour du piano (The Evening Party, or Around the Piano) (Jean Béraud). Oil on wood. Paris, Musée Carnavalet. © Musée Carnavalet / Roger-Viollet / The Image Works.

Many were terrified that the Commune had risen once again—a fear that seemed justified when, in late 1893, a starving young anarchist by the name of Auguste Vaillant threw a bomb into the Chamber of Deputies. (Louise Michel, who in general objected to bombing because it killed women and children, approved of this particular bombing, aimed at those she held responsible for the injustices she so adamantly protested.) A number were wounded, but no one was killed, and so this gesture of hostility toward the state found a sympathetic response among members of the far right, including royalists, deeply conservative Catholics, and anti-Semites, all of whom had their own reasons for detesting the current government. Even certain of the liberal intelligentsia, including Mallarmé, Paul Valéry, and the journalist and critic Octave Mirbeau, sympathized—at least in theory—with anarchists’ fury at the poverty in which so a large portion of the nation was mired.

Vaillant went to the guillotine defiantly crying, “Death to bourgeois society! Long live Anarchy!” But the Chamber of Deputies was determined to put a stop to France’s anarchists, whether simply theorists or actual terrorists, and passed laws restricting the press from printing anarchist theories or propaganda and forbidding “associations of evil-doers.” Thus armed, the police fanned out, raiding anarchist meeting places and issuing warrants. Camille Pissarro, who had long been drawn to radical politics and was attracted by the theory of anarchism, wrote his son, “You must know about the reactionary wind which is sweeping the country now. . . . Look out!”1

Many of France’s leading anarchists now left the country. But instead of shutting down the terrorist threat, the new laws seemed only to incite more violence. Only days after Vaillant’s death, another bomb went off, this time at the Café Terminus, a popular gathering-place at the Gare Saint-Lazare. One person was killed and twenty were wounded. Subsequently, a bomb went off in the Rue Saint-Jacques, killing a passerby, while another exploded in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, where it mercifully did little damage. Still another detonated in its owner’s pocket, as he entered the Church of the Madeleine, and yet another blew up in the chic Restaurant Foyot, where it put out a diner’s eye.

Emile Henry, the young man accused of the Café Terminus bombing, was not at all reluctant to claim credit for this explosion as well as the earlier one that had killed the five policemen. It never was clear whether or not he was responsible for the earlier blast, but under the circumstances, that hardly mattered. Parisians were chilled to hear of his response to the judge, who reprimanded him for seeking to kill innocent people. “There are no innocent bourgeois,” Henry had coldly replied.2

Henry went to the guillotine on May 21, 1894, but this did not put a stop to the violence. Quite the contrary. In June came the most devastating attack of all, the assassination of Sadi Carnot, president of the Republic. Carnot, who was visiting an exposition in Lyon, was riding in an open carriage when his assassin—shouting “Vive la Révolution! Vive l’Anarchie!”—plunged a dagger into his stomach. Carnot had refused to pardon Vaillant or Henry, and he paid the price.

Carnot was immediately given the secular equivalent of canonization, with heroic statues dedicated to his memory going up throughout France, while the shocked Deputies passed a series of repressive laws intended to shut down anarchism once and for all. These laws, which made advocating anarchism a punishable offense and removed anarchists’ rights to trial by jury, also clamped down on all publication of anarchist ideas, including press reports. This in turn stirred up a good deal of fear and indignation among radical republicans and socialists. Pissarro, who was in Bruges at the time, wrote his son that given these new laws, it was impossible to feel safe. “Consider,” he added, “that a concierge is permitted to open your letters, that a mere denunciation can land you across the frontier or in prison and that you are powerless to defend yourself!”3 Under these unfavorable circumstances, he was afraid that he would have to remain abroad for quite some time.

* * *

Despite an undercurrent of panic throughout Paris, life in many ways seemed to go on as usual. Pissarro held a critically acclaimed if not especially lucrative exhibition of his work at Durand-Ruel’s in March, soon after the explosion at the Café Terminus, and returned to France that autumn after deciding that he had nothing to fear, since he was not well-known and had never participated in anarchist activities of any kind.

In March, another important event in the art world took place with the sale of Théodore Duret’s collection. Duret, heir to a lucrative cognac business, had met Edouard Manet in Spain in 1865 and had become one of his closest friends and staunchest admirers. Duret wrote an insightful biography of Manet, catalogued his work, and in the end, served as pallbearer at his friend’s funeral. Manet painted Duret, as did Whistler, who along with Claude Monet was also a good friend. Over the years, Duret had generously supported the Impressionists by purchasing their work and by writing an early defense on their behalf, Les peintres impressionnistes (1878). In time he would also write biographies of Renoir, Whistler, van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Courbet.

But in 1894, Duret had suffered severe business reverses due to the repeated loss of grape harvests, and he was forced to sell much of his collection. The day before the sale, Julie Manet attended an exhibition of the collection, where she spotted one of her mother’s paintings (Young Girl in a Ball Gown) as well as several paintings by her uncle. These included “a portrait of Maman dressed in white on a red sofa with one foot stretched out in front” (Le Repos) and “a small portrait of Maman . . . dressed in black with a bouquet of violets and wearing a small hat” (Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets).4 Like everyone else who has seen this delectable portrait (it now hangs in the Musée d’Orsay), Julie adored it. Her mother bid on this and Le Repos; although Le Repos got away from her, the portrait with the violets did not. Much to Julie’s pleasure, it would soon hang in her own bedroom.

Continuing her browsing, Julie singled out Monet’s painting of white turkeys, which Winnaretta Singer, now the Princesse Edmond de Polignac, also spotted and paid a handsome price to acquire. Julie then took in her uncle’s unfinished portrait of the Impressionists’ nemesis, the critic Albert Wolff, which she thought was quite marvelous—“especially considering how stupid and ugly the sitter is.”5

Unlike Wolff, Degas was a friend, and Julie warmly admired his paintings in the Duret collection. Julie, who was a favorite of Degas, had few qualms about this prickly gentleman, but Renoir, like so many others, was a little more wary. Later that month, when Renoir invited Julie and her mother to dinner, along with Mallarmé and Durand-Ruel, he added that he wanted to invite Degas, but “I confess that I don’t dare.” Yet despite Degas’ past fallings-out with Renoir and his reputation for (as Paul Valéry put it) “scatter[ing] wit, gaiety, terror” at those dinner parties he attended, Degas by 1894 seems to have been on reasonably good terms with Renoir—sufficiently congenial, in fact, to invite him to dinner, after which Degas took a photograph of him and Mallarmé together.6

* * *

The season’s art events continued in April, with an exhibition of Manet paintings at Durand-Ruel’s. A group of Independents, including Pissarro’s son Lucien, were exhibiting in the annex of the Palais des Arts, while the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, re-formed in 1890 as an alternative to the official Salon, held its exhibit at the Champ de Mars. There, Whistler’s portrait of Montesquiou (formally titled Arrangement in Black and Gold) attracted favorable attention. Like so many of Whistler’s portraits, this one had required numerous sittings over the course of several years, and when at last completed, Montesquiou rushed away with his prize before the painter—notorious for clinging to his paintings—could change his mind. Montesquiou then lent the portrait to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, where it was warmly received.

Eventually Montesquiou sold this splendid portrait for an enormous sum—a deed that infuriated Whistler, who felt ill-used. “I painted it for a mere nothing,” he mourned, “and it was arranged between gentlemen.”7 Ultimately Henry Clay Frick would acquire it, adding to the growing unease among the French about the number of French paintings vanishing across the Atlantic.

* * *

And life went on. Clemenceau, now in greatly reduced circumstances, moved to a modest ground-floor apartment with garden on Rue Benjamin-Franklin.8 Here, where he would live for the rest of his long life, he wrote almost daily for his paper, La Justice, and entertained friends—mostly artists and writers.

Maria Sklodowska met Pierre Curie that spring and would become Marie Curie the following year. Zola was seen in the Tuileries gardens (by Madame Daudet, who reported it to Goncourt), scandalously walking his illegitimate family around this most public of places. And Debussy unexpectedly announced his engagement to Thérèse Roger, a soprano who had recently performed his work in public. Their wedding was to be on April 16, but many among Debussy’s acquaintances were dismayed to learn that he had made no move to break off relations with Gaby, who still was living with him—presumably without knowledge of his marital plans.

Ernest Chausson, Debussy’s friend and source of innumerable loans, indignantly wrote a close family member about Debussy’s duplicity. Chausson was especially troubled about the lies that Debussy had told his future mother-in-law, and he broke with Debussy over this. Others in Debussy’s circle were also dismayed. It was a difficult time for Debussy, during which he lost many friends, and in the end he called off the engagement.

That same spring, Oscar Wilde caused a sensation by appearing in Paris with Lord Alfred Douglas, where he was made much of by just about everyone except Montesquiou, who shuddered at his lack of discretion, and Whistler, who by now was a rival and bitter enemy. Many years before, a mutual acquaintance had introduced Wilde to the equally flamboyant and scathingly witty Whistler with the sly remark, “I say, which one of you two invented the other?”9 But by now, the biting wit that shot back and forth between the two had developed a scorched-earth quality—especially as Wilde felt free to help himself to Whistler’s better witticisms, adopting them as his own. This led to a famous exchange, prompted by Wilde’s patronizing acknowledgment of one of Whistler’s epigrams. After Wilde remarked that he wished he had said it, he was met with Whistler’s prompt retort, “Oh, but you will, Oscar, you will!”10

In the meantime, Edmond de Goncourt was caught up in the furor produced by publication of the seventh volume of his Journal. Following the uproar that his previous volumes created, especially the most recent (published in 1892), Goncourt had promised that this would be the last to appear during his lifetime. But then he changed his mind, and in April 1894 the seventh volume began to appear in serialized form in the Echo de Paris. Like the previous volumes, this, too, angered a number of its still-living subjects, who retorted in ways that Goncourt found painful. Goncourt was especially hurt by criticism from his good friend, the novelist Alphonse Daudet. Daudet’s brother had a go at Goncourt first, but then Alphonse had his say as well, mentioning several personal references that had upset him. Bowing to friendship, Goncourt agreed to let Daudet look at the next volume before publication, with the option of cutting anything that offended him. But worse was yet to come, for in June, the Echo de Paris forwarded to Goncourt a particularly unpleasant commentary—an envelope full of soiled rags.

Hostility to the new seemed especially rife that spring in Paris, as the defenders of tradition—already shaken by the threat of political anarchy—took aim at what they regarded as cultural anarchy. Camille Mauclair (in the Mercure de France) indiscriminately attacked all contemporary painters, whether Gauguin, Toulouse-Lautrec, Cézanne, or Pissarro. The untimely demise of Gustave Caillebotte in February, at the age of forty-six, gave rise to an especially nasty hullabaloo. Caillebotte, who had played a key role in the Impressionist movement—both as a generous patron and as a painter of considerable talent—left his large collection of important Impressionist paintings to the state, with the stipulation that this collection be accepted in its totality, to be exhibited first in the Musée du Luxembourg and then in the Louvre. Caillebotte’s bequest immediately set off an uproar reminiscent of the Olympia affair.

Renoir, who was designated as executor of Caillebotte’s will, had the difficult job of negotiating a settlement that would come even close to what Caillebotte intended—a task made almost impossible by the degree of antagonism that Impressionist art still evoked. One of the most vocal of the traditionalist painters, Jean-Léon Gérôme, called the collection “garbage,” while the prominent review L’Artiste, after attempting a questionnaire on the subject, concluded that Caillebotte’s bequest was considered “a heap of excrement whose exhibition in a national museum publicly dishonors French art.”11 Not surprisingly, Caillebotte’s bequest was not easily resolved and would remain an inflammatory issue for some time to come.

* * *

Oddly, Caillebotte’s collection contained no works by Berthe Morisot, an omission that Morisot’s friends took particularly to heart. Realizing that whenever the Caillebotte bequest was settled and its contents hung on museum walls, Morisot would most unfairly be left out, Renoir, Mallarmé, and Duret began to pull strings to ensure that the state purchase one of her paintings, independent of the Caillebotte bequest, for the Musée du Luxembourg.12

The painting that they had in mind was one that had caught Julie’s eye—Jeune Femme en Toilette de Bal (Young Girl in a Ball Gown)—featuring a young woman in a white ball gown draped with white flowers. Duret, who had hung the painting in a place of honor in his home, proposed that Mallarmé pull strings with the director of the Beaux-Arts, who was a good friend. As a result, while all the storm and furor over the Caillebotte bequest was going on, Morisot’s devoted friends were able to make their case quietly to the curators of the Luxembourg and the Louvre. Without any notable fuss, a reasonable purchase price was agreed on, and the state bought Jeune Femme en Toilette de Bal, which headed for the Luxembourg well ahead of any of the paintings by Morisot’s male colleagues in the Caillebotte bequest.

Renoir and Mallarmé continued to look out for the widowed Morisot in other ways as well. Shortly before the Manet exhibit, Renoir wrote to ask if he could paint Julie with Morisot, rather than Julie by herself, as previously arranged. Morisot agreed, and mother and daughter spent a number of pleasant spring mornings sitting for Renoir, followed by jolly lunches with the Renoir family. That summer, when Morisot (attracted by a poster in the Gare Saint-Lazare) took Julie on vacation in Brittany, Mallarmé and Renoir made a point of keeping in touch with her. While in town, Mallarmé escorted her and Julie to Sunday afternoon concerts, and invited her to the theater.

Berthe Morisot was still battling grief, but she was blessed with a lively, appreciative daughter and with friends who cherished her and cared deeply about her welfare. As Renoir once commented to Mallarmé, after a dinner with Morisot: “It must be said that any other woman with everything she has would find a way of being quite unbearable.”13

* * *

One of the painters whose work Julie Manet saw and admired at the spring Duret sale was Paul Cézanne. “Above all,” she confided to her diary, “it’s his well-modeled apples that I like.” She was not alone, for Cézanne, who had long before given up on Paris for his native Provence, was slowly gaining recognition in Paris. A big breakthrough came shortly after the Duret sale, where Julie Manet was not the only one to notice his paintings. On March 25, the influential art critic Gustave Geffroy wrote a very complimentary piece on Cézanne in Le Journal. “There is a direct relationship,” Geffroy wrote, “a clearly established continuity, between the painting of Cézanne and that of Gauguin . . . as well as with the art of Vincent van Gogh.”14

Cézanne was pleased with the article, attributing it to Monet’s influence. After all, Geffroy had long been one of Monet’s biggest boosters, and the two were good friends. The upshot was that in November 1894, Cézanne left his Provençal sanctuary and traveled to Giverny to renew his long-standing friendship with Monet and to meet Geffroy. Until the last moment, Monet was afraid that Cézanne would not come. “He’s so odd,” he wrote Geffroy, “so afraid to see a new face that I’m afraid he’ll give us a miss, despite his keen wish to make your acquaintance.” He then added, “How sad that such a man hasn’t had more support in his life! He’s a true artist and has come to doubt himself overmuch. He needs encouragement.”15

Cézanne did indeed summon up the courage to visit Giverny, arriving in late November. There, Monet introduced him to Rodin, Mirbeau, and Clemenceau, as well as to Geffroy. It was a happy occasion, although Cézanne’s oddities sometimes startled the rest of the company—especially after he took Geffroy and Mirbeau aside to tell them tearfully, “He’s not proud, Monsieur Rodin; he shook my hand! Such an honored man!” And the awkwardness must have been acute when Cézanne followed this up by kneeling before Rodin to thank him for actually having shaken his hand.16

Cézanne seemed to like Geffroy and asked to paint his portrait, with the hope of exhibiting it. At the time, Geffroy lived on the heights of Belleville, directly across from the Butte of Montmartre, and for three months Cézanne came almost every day to his apartment, painting and then lunching with Geffroy and Geffroy’s mother and sister. Unfortunately, Cézanne at last gave up on the picture, saying that it “was too great for his powers,” and returned to Aix. Still, “in spite of its unfinished state,” Geffroy considered it “one of his most beautiful works.”17

During the course of their many lunches and painting sessions, Geffroy came to value the passion and the faith with which Cézanne painted and, indeed, with which he conducted his entire existence. It was a rigorous life, conducted according to self-imposed standards. Not surprisingly, Cézanne imposed similar standards on his peers. Among contemporary painters, only Monet garnered Cézanne’s praise: “Monet!” he would exclaim. “I would place him in the Louvre.” For others, especially Gauguin, he had nothing but contempt. Gauguin, Cézanne would say angrily, had “stolen” from him, from Cézanne’s own discoveries.18

But perhaps most characteristic of the man, according to Geffroy, was his enthusiasm. Only Cézanne could exclaim, with almost childlike gusto, “I will astonish Paris with an apple!”19

* * *

While Cézanne dreamed of astonishing Paris with an apple, Rodin was in the midst of a terrible struggle over his monumental Balzac sculpture. In May, an impatient committee from the Société des Gens de Lettres paid a visit to Rodin’s studio and was alarmed to find that the sculptor had progressed no further than a nude Balzac—a disconcertingly realistic one, with an enormous belly. Rodin was searching for Balzac’s very soul, and given the difficulty of this task, he could set no date for the sculpture’s completion. And then, shattered by overwork and stress, he escaped Paris for a summer of peace and quiet in the countryside.

Unfortunately, the situation had not improved when he returned. The committee declared that the sculpture in its present form was “artistically inadequate,” and yet there was strong feeling among some committee members that Rodin should be instructed to deliver it within twenty-four hours or return his sizable advance. Was it a question of the delivery date, or was it dissatisfaction with Rodin’s vision? Or was it something else entirely? Some among the press, which soon learned of the affair, speculated that an unnamed sculptor who wanted the commission had prompted friends on the committee to do everything they could to upset Rodin and delay the sculpture’s completion. Others believed that the entire imbroglio was simply a maneuver to prevent Zola’s reelection as president of the Société.

In the midst of the clamor, there still were those who were trying to bring the affair to a positive conclusion. After quiet talks with the new president of the Société, Rodin agreed to place the commission on deposit until delivery was made, and he estimated that the monument would be finished within a year. The committee was satisfied with this arrangement and agreed. Unfortunately, this was not the end of the matter; troublemakers once again stirred the pot, leading the committee to try to reconsider its decision. At this point the Société’s president and six committee members resigned.

Their resignation, on November 26, took place only two days before Rodin’s luncheon at Giverny with Cézanne. It was not only Rodin’s friendship with Monet that drew him there at this tumultuous time; it was also the presence of Geffroy and Clemenceau, both of whom had been his staunchest supporters throughout the entire Balzac affair. Rodin well understood the importance of standing by those who stood by him.

Soon after, yet another president of the Société met with Rodin and drew up a contract providing that Rodin’s commission be put into escrow while he completed the statue, for which there would be no time constraints. It was an arrangement that gave Rodin his necessary freedom, even if it meant that he would now have to invest his own money to bring the work to completion.

But he still had to bring that work to completion—along with two separate monuments to Victor Hugo (for the Panthéon and the Jardin du Luxembourg) and The Burghers of Calais.

* * *

Throughout the last half of 1894, Debussy—now free from marital entanglements—was working on what would turn out to be three masterpieces: his opera, Pelléas et Mélisande; his early sketches for the three orchestral Nocturnes; and his Prélude à l’Après-Midi d’un Faune (Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun). This last work, first performed on December 22, brought him his first success, even if no one at the time recognized it for the groundbreaking masterpiece that it was. Debussy had been inspired by Mallarmé’s poem L’après-midi d’un faune, published in 1876 in a limited edition illustrated by Edouard Manet. In 1890, Mallarmé took note of young Debussy and asked if he would be interested in collaborating in a theatrical production of L’après-midi d’un faune. In the end, Debussy’s inspiration did not take this particular form, but Mallarmé—although surprised when he first heard Debussy play the work on the piano—commented (as Debussy later recalled) that “this music prolongs the emotion of my poem and conjures up the scenery more vividly than any colour.”20

The audience was similarly enthralled. As the conductor, Gustave Doret, later described the occasion, “I felt behind me, as some conductors can, an audience that was totally spellbound.” It was, in his words, “a complete triumph,” and accordingly he did not hesitate to break the rule forbidding encores. The critics, irritated by the encore, were less charitable, but in the years to come their reviews would disappear into the dust. As Pierre Boulez would later put it, in this work “the art of music began to beat with a new pulse.”21

* * *

“Ultimately,” Debussy wrote to a friend that summer, “we must just cultivate the garden of our instincts and officiously trample on the flower-beds all symmetrically laid out with ideas in white ties.” No one had ever claimed that this kind of work was easy, and that autumn he wrote to the Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe that he was “feeling like a stone that’s been run over by carriage wheels.”22

Across town from Debussy, on the Left Bank, Alphonse Mucha was experiencing much the same feeling—although his depression was due less to exhaustion from staying the course than to a sudden lack of work, coupled with the fact that it was Christmas. Alone and depressed, he found himself proofing some lithographs for a vacationing friend. He was just finishing up when fate suddenly intervened—in the form of Sarah Bernhardt.

The manager of the print shop rushed in, all in a panic. Sarah Bernhardt, the divine Sarah herself, had just telephoned to demand a new poster for her current play, Gismonda. Not only that, she wanted it by New Year’s Day. It was impossible! There were no available artists who could do such a job. And then the manager looked thoughtfully at Mucha. Could this young man, still virtually an unknown, produce a work that would please the great Bernhardt?

It was worth a try, and Mucha was more than willing. And so the young man set off for the glorious Théâtre de la Renaissance (which Bernhardt had bought after selling the Théâtre de la Porte-Saint-Martin), where Gismonda was playing. Enchanted with Bernhardt, Mucha immediately set to work creating the poster that would change his life.

Where did the ideas come from that set him off in this completely new direction, so unlike anything he had ever done before? No one knows, although it is true that for some time Mucha had been soaking up ideas from his colleagues at the crémerie. These influences included Symbolism and the Japanese art that were sweeping avant-garde Paris, as well as the curved, organic elements of the emerging Art Nouveau movement—although Mucha himself was convinced that his only source of inspiration was the Czech tradition of folk ornamentation.

But Mucha, much as Debussy advised, now cultivated the garden of his instincts, and the Gismonda poster that emerged was something uniquely and even startlingly his own. The manager and owner of the print shop were in fact horrified by what they saw; they sent the poster off to Bernhardt only because they felt they had no other choice. Sunk in gloom, Mucha awaited the verdict.

Bernhardt loved it. Summoning Mucha to the theater, she immediately signed him to a six-year contract to design not only posters but also sets and costumes. In time he would design her jewelry, advise her on hair styles, and select the material for her dresses off-stage as well as on. But it all began with his Gismonda poster. When it appeared on New Year’s Day, it became the talk of the town. Nothing like it had ever been seen before, and the public scrambled to get copies. (A shrewd businesswoman, Sarah ordered four thousand more to sell at a profit.)

According to Mucha’s son, Bernhardt became for Mucha “the ideal woman; her features and even the way she dressed, in flowing robes spiraling round her slim figure.” These Mucha “transformed and etherealized” in his posters (he created a total of nine for her). He would soon become a successful designer, painter, and sculptor, eventually returning to the land of his birth, where he spent the last thirty years of his life painting the epic history of his homeland.

By the end, all the posters and pursuits of his Paris years had become for him a frivolity. Yet it is as a poster artist that he is best remembered—not only of Bernhardt, but also of numerous unknown models, all beautiful and flower-wreathed, with swirling gowns and long, flowing hair. Despite his rejection of the term “Art Nouveau” (“Art is eternal,” he protested, “it cannot be new”),23 Mucha soon became its foremost exponent, leading many Parisians to refer to Art Nouveau itself simply as the “Mucha style.”

* * *

Yet while life in the theater, the art galleries, and the cafés—as well as in the slums—went on much as usual, Paris and all of France was about to be shaken by a storm far more devastating than the Panama affair and far more destructive than any anarchist bomb.

The ingredients for this social and political explosion had been present for some time: the festering wound to national pride inflicted by Germany in 1870–1871, and the corresponding humiliation suffered by the French army; the long-standing hostility between republicans and monarchists, and the comparable enmity between the Republic and the Church; an ongoing economic malaise, especially in the agricultural sector; and, most troubling of all, a rising tide of virulent anti-Semitism.

It was a nasty mix, but so far even the Boulanger affair and the Panama scandal—although coming dangerously close—had not been enough to ignite it. But now, in December of 1894, the fatal spark was about to emerge.

Its cause was the conviction of a young Jewish artillery officer for treason. His name, Alfred Dreyfus, would soon call forth the full range of fear, hate, and misguided national pride that was France’s burden as the century drew to a close.