The Brief Aeronauts

~ Charles Wilkinson

The haunted lawn: not be photographed; its full condition only half-glimpsed, even by the imagination; a hint of mist; what rises from the bone-broth; a ghost in the ground; some things eat the grass.

At the end of a dirt track, always muddy, except for three days at the height of summer, it's the house you see first; gray stucco over pale red brickwork that shows through in patches: grazed flesh and sickening skin. A wooden door pillaged four centuries ago from a slighted castle three miles up the road. The curved arch over the lintel, a later addition, and a pitched roof, slates missing, the worst holes patched with blue tarpaulin. Diamond-paned windows, a few smashed. On the far side, the lawn stretching out beneath the hill is frayed. Hogweed and ferns thrive in the flowerbeds.

All who live in the parish know the house is Hexter Hall, the name too grandiose for a yeoman's cottage hiding beneath a late Victorian facade. You will not be invited inside, and neither will I. So let's enter with the fumes from the log fire. A tall thin man who comes from a long line of tall thin men lies on a sofa. He is coughing, possibly because of the smoke that hangs across the room like lace; but his chest is congenitally weak. Conceivably he was wheezing and spluttering before the match was lit.

On the far side of the room, next to the only window, not so dirty as to exclude rather than admit light, a middle-aged man in a blue blazer sits on a Windsor chair. He brings with him a whiff of sea salt and polished brass. A member of a yacht club, this is what you imagine. I'm unconvinced, for Hexter Hall is far from the coast. The man opens a brown leather briefcase and produces two glossy magazines devoted to aviation and aeronautical matters.

"With our compliments," says the man, whose name you are now told is Justin Buckey. "We're so grateful you've agreed to be interviewed. In addition to your fee you'll be given three complimentary copies of the issue in which our conversation appears."

As he moves to place the magazines on a low table next to the sofa, something invisible touches his face. A soft irritation over the eyes. A spider's web? He brushes it away; then looks at his hand. No silk on the palm.

"You'll stay the night, of course," replies Ned Hexter, not reaching out for a magazine "We're very quiet here as a rule. Imogen will be delighted to have company at supper. Our son's coming back from London. But not till tomorrow."

Hexter is dressed in a dung-beetle-brown corduroy suit and a moleskin waistcoat. His sandals, worn over thick green socks, are propped on the armrest at the far end of the sofa. His head is supported by a threadbare velvet cushion; his long thin face, crowned by white hair that might once have been red, is pale and dominated by the kind of straight nose seen in paintings of medieval monarchs. The mouth beneath: pale rose pink and pursed. I wonder if you've met anyone like Hexter? Justin Buckey has not.

It's humid outside. How many degrees warmer than Hexter Hall, which has no central heating? Not an inkling this afternoon that the lawn is inhabited. We cannot hear the worms underneath or the moan of the trapped ghost. The hedge at the bottom of the garden is rust-brown; killed three years ago by frost. I have a good view of the back of Hexter Hall, one I'm willing to share with you. Most of the stucco has long since fallen off, exposing shoddy brickwork and beams that no one has bothered to paint black. On the ground floor, there is a sash window with several clean panes. The roof tiles are no longer visible beneath the moss. An unstable chimney stack is pointed with nothing stronger than grass. You ask when we can make our way over the weed-riddled lawn and then peer through the window. If we can no longer listen in, at least we can watch them. You follow me as I drift over to the window. The dark brown furniture is too large for the room; the pictures in sumptuously carved and gilded frames must once have hung on far higher walls. They have the merit of concealing the damp. Ned Hexter has risen from the sofa and is warming the back of his long legs by the log fire, which has ceased smoking. Justin Buckey still sits in the Windsor chair. He has been writing in a notebook. What are they talking about? you ask. It is time to inveigle ourselves through a crack in the glass.

Ned Hexter has been speaking mainly of his family history and helicopters, I reply; I thought to spare you the former; much of it is tedious. Now we will hear them plainly.

"I dream of it every night, falling out of the sky in flames," says Hexter.

"There were no survivors."

How could there have been? On impact, it crumpled like an insect. Anyone who hadn't already been asphyxiated or burnt to death would have died as soon as it hit the ground."

"And the helicopter's design?" Buckey begins carefully. "Do you feel . . . well, later some your ideas were adapted with great success."

For a long time, Hexter stares straight ahead. Is he thinking of the men who died or his failure to take out a patent? It is hard to tell, but from our position just inside the room all we can see is the harrowing grief that has condensed his flesh till the skin is taut across his bones. He nods and replies so softly as to be barely audible: "It was a beautiful machine. Beautiful things are often dangerous." He moves away from the fire. "But you must be hungry. I eat very little these days. But there is cake . . . or something . . . in the kitchen. You'll take a cup of tea, at the very least?"

"Yes, tea will be welcome. And whatever else is most convenient."

"I'm afraid that Imogen won't be able to join us. I still have hopes that she may be up to a little supper."

"Your wife. Is she ill?"

Hexter pauses for a moment, as if considering a fine point of law. "Let us say she has changed greatly during these past few months."

"Nor herself?"

"Quite! Now if you'll excuse me."

What you cannot know, and neither Ned nor Justin could be aware of, is that Adrian Hexter, heir to Hexter Hall, its damp rooms, the half-dead lawn and colony of spiders, is at this moment making his way along the road. It will be minutes before he reaches the dirt track. There is no interest in seeing Ned search the cupboards for a cake tin or watching him brew tea in a chipped brown pot; neither is observing Buckey turning the pages of his leather- bound notebook of any significance. From a window over the porch we will witness Adrian's approach.

What should we discuss while we wait? You wish to learn more about Ned Hexter. Why is he living in a ruinous house with no central heating? First, you must understand that none of the Hexters last for long. Note their portraits on the staircase; the line of lineage-proud, short-lived men ascending to the second floor, complete with pictures of their willowy, swan-faced wives. A Hexter would never marry anyone who was not thin and tall. Throughout history most Hexters have, on reaching the age of majority, started well, but few survived long enough to consolidate their achievements. During the infancy and childhood of every succeeding heir, ground was lost: socially, financially - and often literally. The estate has dwindled to the Hall, with its legacy of a haunted lawn.

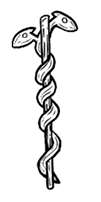

Ned Hexter talks mostly of helicopters. His family history is a subsidiary interest; he is the longest lived of all the Hexters. He trained as an aeronautical engineer. His ambition, fulfilled with fateful consequences, was to create the most elegant machine ever to take to the air. Whilst capable of carrying a sufficient complement of men to make it a commercial and military proposition, it proved slender, no ungainly pot-bellied troop carrier. Its blades were narrow; almost invisible once airborne. It was perhaps the most silent of helicopters ever designed, rising without undue disturbance, though its thrust and lift were evident as a flattening of grass. I have a photograph of one here. The early model was painted sky blue. Hexter hoped that once sufficient height was gained they would be imperceptible; even on cloudy days seeming no more than a patch of the blue breaking through. He saw them as combining grace, stealth and resilience, as secret as anything made of metal could be in the sky.

But now Adrian Hexter is at the end of the dirt track. Though it is drier than usual, it is still sticky beneath the overhanging beech trees. He moves fluently and at great speed, as if there were not a ridge of dried mud or a pothole beneath him; his progress is preternaturally linear. Like his forebears, he is long-limbed. Is he taller than any of them? This is surely not unlikely. You say he seems less substantial. He is wearing a transparent overcoat, somewhat shimmering. An odd way to dress on a balmy afternoon.

We must go downstairs now. The tea has brewed. Ned has found a walnut cake; it sits igneous and dangerously brown in the centre of the table. Will the knife be sharp enough to cut it?

The first cup has been poured when the front door is opened and then banged shut. Ned stands heron-like, tea pot in hand. No visitors are expected.

"Who can that be? We are so seldom disturbed at the Hall."

"You mentioned your son . . . earlier," Justin reminds him.

"Not expected until tomorrow. It would be most unlike . . ."

Then Adrian is in the living-room: a rush of thrashing arms and legs. He's taller than seems strictly conceivably and appears confused. After striking his head on a beam, he sinks into an armchair. His upper body is clad in some kind of waterproof, although the arms are covered by a different material, almost translucent and made of a delicate fabric.

"Well, this is unexpected," Ned remarks. "I'm sure you'd like to see your mother. Unfortunately she's indisposed. We had hopes she would join us for supper, but I suspect that will not now be the case."

"Sorry . . . I'm early. I need to change. That's the problem," said Adrian. His voice is high-pitched yet dry; almost nothing more than a faint squeaking and scraping at a window pane.

"There is nothing to prevent you from changing upstairs. But first I should introduce Justin Buckey. From Aviation and Aeronautical News. He's interviewing me."

"Really? I expect to fly soon."

The expression on Buckey's face is one of comprehensive perplexity. He is at a loss to know who or what is addressing him: in English to be sure and the content ordinary enough. But he has never been spoken to in such unfamiliar tones. Finally he manages: "Where to?"

But Adrian has already lost interest. Now it's the orange glow of a lampshade that attracts him.

"Cake, Adrian?" asks Ned. If he is in any way discomfited by his son's appearance and manner, he is disguising it.

"No, thank you, Father. I'm . . . hardly eating at the moment."

"Very well. Perhaps it would be best if you change now. I hope you'll manage a little something for supper."

Adrian has risen unsteadily to his feet; his thin legs look as if they are on the verge of crumpling beneath him. For a moment, he is unsure where to go next. He seems incapable of anything more than imbecilic arm-fluttering. Then he regains control of his body and flickers across the room to the foot of the staircase.

"Now you were asking about the Hexter A6 Helicopter."

"Ah yes," says Buckey, floundering.

"You'll have heard it said that it was a flimsy machine. But the problems were less to do with the design than the materials. The crash was most regrettable, of course."

When Buckey next looks towards the staircase, there's no sign of Adrian. The sounds from above seem almost indefinable, although they could be the old beams settling or a disturbance in the water pipes.

You've seen the photographs and the footage, the machine slowing for a few seconds, suddenly losing height, clipping the top of the canopy on the way down. Then from a different camera, some way off: a view of open fields, the wood in the middle distance. The gray-black smoke rising. Afterwards, the spidery wreckage: the blades twisted, the rest a blackened abdomen. Of course, Hexter refused to accept the blame, although that didn't prevent recriminations and the court case.

In his study, you'll see the designs for the Hexter A6 framed on the wall. And here's an oil painting he commissioned of the A7, flying over the Oxfordshire countryside: as close to being airborne as a machine that never got off the drawing board can be. Hexter believes that his plans were stolen. These box files contain letters from solicitors and counsel. The case went against him. Some thought him unlucky. There hasn't been much to spend on the Hall since then. Lawsuits alleging his intellectual property had been stolen added to the debt. He had to sell what little farmland there was on the estate. He was left with the house and the lawn.

Here's his desk and on the top of it a photograph of Imogen, taken at an air show in the years before the crash. It must have been a cold day for her to wrap up like that. It's only her face that tells you how thin she was. See how the wind has caught her long yellow hair; for a moment, a bright flare on a gray lusterless day. She's in her room now and Adrian's asleep in his. If you listen carefully you can hear Ned cooking supper in the kitchen below. Now it is evening the house is colder. In the living room, Buckey is pacing up and down, plotting tomorrow's early departure. When we slip downstairs, I'm sure that, with Ned out of the room, we'll see him place another log on the fire.

Ned's serving some anonymous meat and thick gray gravy from an orange casserole dish. There's bread in a basket in the middle of the table. Buckey must wonder whether it's warmer in the kitchen. Then he starts. Something small, a moth perhaps, is nibbling at the nape of his neck.

"I'm afraid Imogen is indisposed," says Ned, once he's sitting down. He offers Justin a glass of water. "A pity. She was such an enchanting conversationalist and a great deal better informed about helicopters than one might imagine."

"And your son. What is he reading at university?"

"Aeronautical engineering. Now you may think that is perfectly predictable. But it's become clear that in important respects he takes after his mother."

"Oh!"

"He's started to lose his appetite. I do think it's so important to eat something, don't you agree?"

"Yes," Justin replies, pushing the meat to one side of his plate and toying with the gravy.

"Of course, these days Imogen eats practically nothing. A little honey perhaps."

"What does her doctor say?" asks Justin, as he examines a bread roll.

"Nothing. She hasn't got one."

"Mightn't it be a good idea to . . ."

"No, they're hopeless when it comes to people with Imogen's condition. I've done what I can. Made certain modifications."

"To help her get around the room."

"Yes, I suppose you could say that. She lost a leg the other day."

Hexter speaks of helicopters till late in the evening. Justin is tired by the time they climb the staircase. His host stops to listen at Imogen's door, but there is no sound apart from a noise that might be two of the softest, most fragile things in the world being rubbed together.

From his bed Justin cannot hear Alex in the next room, alighting for a moment on objects, knocking against the walls and then pressing his face to the window pane; for now it is dark, his only desire is to reach the moon.

It's past seven in the morning when Justin makes his way down the staircase. The house is silent. Every piece of furniture seems less itself, as if hiding the potential for use: the table not designed for anything to rest on it, flowers in a vase or a book, but simply an object constructed from wood. He imagines he's first to get up; then through the one good window he spots Ned Hexter on the lawn. He goes out of the back door to join him. It's a fine day, all the more to be valued for being in late summer. The blue above them has the high gloss of a finished product.

A stretch of lawn closest to the pavement is rife with wild flowers and weeds: yarrow, sheep's sorrel, speedwell and coltsfoot. Further on it's studded with plantains smothering the grass. Hexter's standing towards the back, where little flourishes. In spite of the recent rain there are dry, yellowish-brown patches.

"I'll be off soon," says Justin. "I might beat the worst of the rush hour in town."

"Have you seen Adrian?"

"No, not since last night."

"I hope he's up soon. That boy needs to mate."

"Well . . . I think I'd better . . ."

"You're not going yet . . . surely. There's a lot to tell you. After the crash, I went abroad for a year. One of the mothers kept on coming round here. She was quite mad. Making all kinds of accusations. When I returned, the people in the village told me that she'd buried her son's bones right here in the lawn. I've never found them. He was the pilot."

"Do you think he's here . . . beneath us?"

"Not directly. They'll rise soon, but the pilot's ghost won't be with them Although there are days when I know there has been some kind of . . . anyway, you must meet Imogen before you go."

"That's very good of you, but if you don't mind . . ."

"Come on, she'll be most upset if you leave without saying a word."

Hexter's shepherding him back into the house, past the suitcase, which is packed and waiting in the living-room, and up the staircase.

"I'll give Adrian a call first if you don't mind. The window of opportunity is limited. They don't live for very long, the original species." Ned raps on his son's door three times: no reply. "It could happen any time soon. You don't want to miss it." Then turning to Justin: "Incredible! The lassitude of late adolescence."

"Yes, I've one of my own."

Hexter moves on down the corridor and without knocking enters Imogen's room.

"She doesn't seem at her best this morning," he says, signaling to his guest to come in. It takes Justin more than a moment to comprehend precisely what is in front him. The room is empty, apart from a life form he is initially unable to identify. Later he will attribute this to the fact that even the most commonplace creature will be difficult to recognize if magnified perhaps a million times or more. It is evidently an insect of some sort. It has six long legs that appear pencil-line thin in comparison to the mass of the segmented abdomen. The head has compound eyes and antennae, but also a mop of what looks like yellowish-gray human hair. The lips, supple and feminine, are larger than expected, still capable of kissing. The wings are intricate and translucent.

"She lost two of her legs recently. I've replaced them with very fine steel prosthetics. The slightly shinier ones. Do you see? They seem to be holding up well, but one of her own might break off at any minute. So very fragile, alas!"

"I'd better . . . or I'll miss . . ."

"Hold on! Imogen, this is a Mr Buckey. He's something of an authority on helicopters."

The dry sound of a wing brushing against the wall; a metal leg flexing; a pink tongue protrudes—a response?

"Simply must dash. It's been wonderful to . . ."

Then down the stairs and into the living-room. As Justin picks up his suitcase and makes for the front door, he spots Adrian bumping softly against a window pane. Although his waterproof has turned into two wings, his face, refined by inbreeding, is still recognizable. His hair has gone. A full transition appears imminent.

As Justin runs down the drive, his suitcase swinging beside him, a crane fly, its movements marvelously coordinated, is swimming through the liquid gleam of late summer air; not clumsy, as it would be inside, but an athlete of the insect world. Within seconds, another has passed him, and then a third. The aeronauts are out to play. Rapturous and long-legged, the crane flies have risen from the lawn. Look how they make love on the wing!

Black eggs in the soil. I have been Hexter, Buckey, Adrian, Imogen, the table, a staircase, a teapot and more besides. I thank you for your time. Let's not wait for winter under the lawn: the pilot's ghost, the leatherjackets feeding on roots. In a dark corner of a room, a ten-day- old crane fly will die, withered by the quest for light, its last flight ending away from the beautiful, dangerous sun.