2

A Historical Perspective on Research Related to Ultra-High Temperature Ceramicsa

William G. Fahrenholtz

Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, MO, USA

2.1 Ultra-High Temperature Ceramics

Historically, the boride and carbide ceramics that we now classify as ultra-high temperature ceramics (UHTCs) have been known by a number of different names including refractory borides or carbides [1–4], oxidation-resistant diborides [5], ceramals or cermets [6, 7], and hard metals [8]. Although the term ultra-high temperature was not used in any of these early reports, the aerospace community recognized the need for materials that could withstand the extreme temperatures and chemically aggressive environments. For example, reports from the late 1950s and early 1960s from the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and its follow-on agency the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) described the need for rocket nozzles and thermal protection systems [2, 6, 9, 10]. In particular, Reference [10] identified heat sources associated with atmospheric reentry and rocket propulsion as well as the needs related to leading edges, acreage, and propulsion components. The report provided a series of recommendations for future studies, and some of the pertinent recommendations are summarized in Table 2.1. Interestingly, some of the needs identified more than 50 years ago continue to be cited as priorities for current research. The Streurer report also defined heat flux and time regimes in which different types of thermal protection systems would be most effective [10]. As shown in Figure 2.1, convection and radiation cooling could be used for long-duration exposures at heat fluxes below about 40 BTU/ft2·s (~45 W/cm2), whereas a heat sink approach could be used for short-duration (i.e., <0.3 min) exposures for heat fluxes up to about 1000 BTU/ft2·s (1130 W/cm2). Either ablative materials or transpiration cooling was recommended for heat fluxes above 1000 BTU/ft2·s (1130 W/cm2).

Table 2.1. Selected recommendations for future research and development activities related to UHTCs from Reference [10]

| Recommendation number | Recommendation |

| 10 | A systematic investigation on the application of TPS to solid propellant rocket motors to include (i) transpiration, (ii) evaporation cooling, (iii) chemical reaction cooling, (iv) heat sink, (v) radiation, (vi) film cooling, and (vii) ablation. |

| 12 | Studies on the materials behavior at extreme temperatures, and establishment of thermal and other pertinent material properties at extremely high as well as extremely low temperatures. |

| 13 | Development and introduction of standard test methods for the establishment of performance data for TPS. |

| 16 | Reduction of efforts in short-time high-heating-rate ablative systems for ballistic nose cones, as all present and foreseen requirements can be adequately met with achieved capabilities. Remaining efforts should be directed toward a wider variety of potential material systems. |

| 18 | Reduction of present extensive efforts of theoretical treatment of TPS in favor of technological approaches as outlined in (12) above |

Figure 2.1. Summary of types of thermal protection systems as a function of heat flux and exposure time from Reference [10].

Although the term UHTCs is a recent development, the term extreme associated with the application environments began to appear in the ceramic refractories literature in the late 1950s. Extreme was used to refer to temperatures of 2500°F (~1400°C) or higher [11, 12]. The broader term ultra-high temperature emerged in the 1960s and found more widespread use in Japanese articles through the 1990s [13–16]. Terms similar to ultra-high temperature ceramics started to appear in a series of reports and papers when the current wave of interest in these materials started in the United States in the late 1980s and early 1990s [17–21]. Reference [20] is notable as it clearly defined the ultra-high temperature regime in terms of temperature (above 3000°F or ~1650°C) as well as providing a minimum strength target (greater than ~150 MPa) for materials at ultra-high temperatures (Fig. 2.2). The NASA report [21] seems to have been particularly influential in solidifying the use of the term UHTC as it clearly identified this class of materials as candidates for hypersonic aerospace vehicles. The subsequent Sharp Hypersonic Aerothermodynamic Research Probe (SHARP) tests drew significant attention to UHTCs. In particular, the SHARP B-1 and B-2 tests as well as the related NASA reports identified UHTCs as potential candidates for the hypersonic flight environment despite failure of the UHTC strakes due to problems traced back to processing issues [22, 23]. The term UHTC and the recent resurgence of interest in research on boride and carbide UHTCs seem to have grown from these studies as well as those from a select group of other researchers [24–26].

Figure 2.2. Strength as a function of temperature for several engineering materials along with a clearly defined Ultra-High temperature regime from Reference [20].

2.2 Historic Research

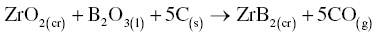

The synthesis of boride and carbide compounds began to draw the interest of researchers in the late 1800s and early 1900s. For the diborides, Tucker and Moody reacted elemental zirconium and boron to produce ZrB2, although they described the compound as Zr3B4 [27, 28]. McKenna later reported the synthesis of ZrB2 by carbothermal reduction according to Reaction 1 at 2000°C [29]. In contrast, reports of the formation of HfB2 were much later, presumably due to the difficulty of separating Hf from Zr [30].

Henri Moissan was an early pioneer of research on carbide materials with over 600 scientific publications identified in a literature search.b Even though Acheson was the first to report a commercially viable synthesis process for SiC [31], Moissan's research on SiC [32], as well as the carbides of Mo [33], Ti [34], and Zr [35] was notable because of its breadth and depth. After the initial reports, scientific publications on borides and many of the carbides were sporadic, but progress was made in areas such as bonding [36], electrical properties [37], and electronic structure [38] through the first half of the 1900s. Although limited in scope, these early studies set the stage for the progress that would result from later studies.

2.3 Initial NASA Studies

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, NASA (and its predecessor agency NACA) began to search for materials that could be used in the extreme environments associated with rocket propulsion and atmospheric reentry. The agency was exploring supersonic flight with vehicles such as the Bell X-1, which was the first plane to fly faster than the speed of sound, as well as a variety of concepts for hypersonic aerospace vehicles [39]. NASA conceived, studied, and tested both blunt body and lifting body designs [40]. Even in the early 1950s, NASA recognized that current materials technologies were not adequate to enable their future vehicle needs and began to search for suitable candidates [6]. For rocket motors, extreme temperatures were predicted for some applications, so the list of candidates of interest was limited to materials with melting points above 6000°F (~3300°C) including tungsten, pyrolytic graphite, hafnium carbide, and tantalum carbide [2]. In contrast, a wider variety of materials were needed for the thermal protection systems of future manned and unmanned vehicles. The agency recognized that their array of planned vehicles would present a wide variety of thermal loads based on the trajectories and other needs of specific missions [10]. For example, significant differences in heat loads were identified based on whether vehicles would land vertically as was planned for the Mercury program or horizontally as was foreseen for winged vehicles (Fig. 2.3) [41]. Because of the possible trajectories that were being considered (Fig. 2.4) and the different possible wing leading-edge radii [41], a variety of materials were considered candidates including refractory metals, ceramics, and cermets [42]. At this point, heat loads could be predicted, and the fundamental design principles used to develop thermal protection systems for specific trajectories had been established, but neither standardized evaluation tests nor design databases populated with candidate materials were available [10]. Availability of standardized tests and design data is a problem that persist for sharp leading-edge vehicles to the present day. These early studies also motivated the U.S. Air Force to explore vehicle designs with higher cross range, which motivated interest in transition metal boride compounds. Ultimately, the blunt body Space Shuttle Orbiter was selected as the first reusable atmospheric reentry vehicle based on cost and mission flexibility [39]. However, the early studies showed the potential advantages of hypersonic vehicles with a high lift to drag ratio such as substantially higher cross range.

Figure 2.3. Notional temperature requirements for orbital reentry vehicles based on projected wing loading and hypersonic lift-to-drag (L/D) ratio from Reference [41].

Figure 2.4. Trajectories and methods for dealing with heat loads from Reference [41].

2.4 Research Funded by the Air Force Materials Laboratory

Beginning in the early 1960s, the U.S. Air Force funded a series of studies that focused on refractory diborides and carbides as candidates for a number of potential future aerospace vehicles. For this manuscript, the research has been divided into three main categories: (1) initial thermodynamic analysis and oxidation behavior; (2) processing, properties, oxidation, and testing studies; and (3) phase equilibria research. Each of these areas is discussed in the following subsections.

2.4.1 Thermodynamic Analysis and Oxidation Behavior

Through the first half of the 1960s, the U.S. Air Force commissioned studies focused on the thermodynamic properties of refractory compounds, including the borides, carbides, and nitrides. Broad-based studies at AVCO produced fundamental thermodynamic property data for an extensive number of borides, carbides, and nitrides [43]. Data generated as part of that project continue to be cited today in references such as the NIST-JANAF tables [44]. Building on the AVCO studies, investigations at Arthur D. Little, Inc. focused on the preparation and characterization, thermodynamic data, and reaction kinetics of ZrB2 and HfB2 [45]. These investigations had a number of notable outcomes. The materials studied in this project were produced using zone melting techniques to remove impurities and minimize porosity. As shown in Figure 2.5, both ZrB2 and HfB2 exhibited parabolic oxidation kinetics over wide temperature ranges, with HfB2 having lower overall rate constants based on lower mass gain. This research resulted in a number of scientific publications describing the oxidation of nominally pure diborides that continue to be referenced today [46, 47]. This research also provided fundamental thermodynamic data including heat capacity values for ZrB2 and HfB2, which were more accurate than previous reports because of the higher purity of the materials examined in this study. In addition, Arthur D. Little performed early research on the oxidation of silicide compounds [48].

Figure 2.5. Comparison of kinetic rate constants for the oxidation of ZrB2 and HfB2 as a function of temperature [45].

The U.S. Air Force also sponsored several projects that examined the thermodynamic aspects of refractory compounds. Research at the National Bureau of Standards (NBS; now the National Institute of Standards and Technology of NIST) examined the heats of formation of ZrB2, AlB2, and TiB2 [49]. The NBS report is notable because of an extensive literature review of the synthesis of the borides of Al, Ce, Cr, La, Mg, La, Mo, Nb, P, Si, Sr, Ta, Th, Ti, W, U, and V. Other research examined the oxidation of carbides [50] and the vaporization of refractory compounds including ZrO2, HfO2, ThO2, ZrB2, and HfN [51]. More than 50 years later, the fundamental research sponsored by the U.S. Air Force continues to serve as the basis for understanding the thermochemical stability of borides and carbides.

2.4.2 Processing, Properties, Oxidation, and Testing

ManLabs, Inc., a small research and development company located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was the lead contractor on a series of projects focused on boride and carbide ceramics. These projects started in the early 1960s and continued into the 1970s. A number of notable accomplishments were achieved, which resulted in the publication of a large number of highly detailed technical reports as well as a series of publications in scientific journals. While the focus was on using commercially available materials, the team provided feedback to suppliers such as improving the purity or reducing the particle size of the starting powders. In addition, several specialized pieces of equipment were produced for processing, characterizing, and testing these materials due to the extreme temperatures involved. The projects were divided into three different focus areas. In the first series, candidate materials were screened along with the evaluation of processing and characterization methods. The second series focused on measuring and understanding the properties of ZrB2 and HfB2 ceramics. The final series of reports focused on the evaluation of boride-, carbide-, and graphite-based materials in relevant environments. This subsection attempts to capture some of the research highlights from each series of reports in roughly the time sequence of the projects.

The first series of studies at ManLabs examined TiB2, ZrB2, HfB2, NbB2, and TaB2 as potential candidates for hypersonic flight and atmospheric reentry applications [52]. Based on literature reports of melting temperatures and thermochemical stability, borides were identified as promising candidates. This first study focused on gathering chemical, physical, and thermodynamic property data for candidate materials from literature sources and then identifying the most promising materials for further study with some initial oxidation testing. Based on oxidation rates, HfB2 and ZrB2 were selected for further study. The follow-on study examined the effect of boron-to-metal ratio (B/Me) on oxidation behavior, thermal conductivity, emissivity, and electrical resistivity [53]. This study also reported extensive evaluations of the densification behavior of ZrB2 and HfB2. While stoichiometric ZrB2 and HfB2 could not be hot pressed to relative densities of more than 98% with grain sizes of less than 50 µm, altering the B/Me ratio improved densification. As shown in Figure 2.6, ZrB2 with a B/Me ratio of 1.89 could be hot pressed to nearly full density at 2200°C without exaggerated grain growth. The plot also shows that hot pressing at 2300°C resulted in a limiting density value of less than 95%, which was attributed to entrapped porosity. Further analysis of density as a function of grain size and sintering time (Fig. 2.7) was used to elucidate the densification mechanism. Densification was attributed to grain boundary diffusion through a thin liquid film where impurities were concentrated. This study also examined the oxidation behavior of the nominally pure diborides as well as diborides with additions of Si or MoSi2. While detailed kinetic studies were completed as part of a project described later, this project did define regimes of behavior for protective behavior (i.e., below ~1200°C for nominally pure ZrB2) and linear kinetics that are still in use today. The report ended with sections describing the thermodynamic stability and phase equilibria of the diborides that were based on literature reports and thermodynamic calculations. The most important outcome of the first two studies was that it motivated additional projects that were more focused on fundamental research on the processing, microstructure, properties, and performance of boride ceramics.

Figure 2.6. Relative density as a function of sintering time for ZrB2 with different B/Me ratios [53].

Figure 2.7. Analysis of densification behavior of ZrB2 (B/Me ratio = 1.89) as a function of densification temperature where t is sintering time and GS is grain size [53].

In the second series of studies, borides with carbon and silicon carbide additions were examined. As part of this project, a series of ZrB2 and HfB2 compositions were formulated and densified. The addition of SiC was examined to improve the oxidation resistance of the diborides while carbon was added to improve thermal shock resistance. The same materials were examined through the entire series of reports, which were separated based on the focus. Some of the important compositions that were developed are summarized in Table 2.2. These reports were highly influential in later studies by narrowing the focus to ZrB2 and HfB2 and identifying the addition of 20 vol% SiC as the optimal composition based on densification, mechanical properties, and oxidation behavior.

Table 2.2. Compositions examined in the second series of studies by ManLabs [54]

| Designation | Major phase | Additive(s) | Composition range |

| I | ZrB2 | None | |

| II | HfB2 | None | |

| III and IV | HfB2 | SiC | 10 – 50 vol% |

| V | ZrB2 | SiC | 10 – 50 vol% |

| VII | ZrB2 | SiC and C | 14 vol% SiC, 10 vol% C |

| XIV | HfB2 | SiC and C | 14 vol% SiC, 10 vol% C |

| XII | ZrB2 | C | 20 vol% C |

| XV | HfB2 | C | 20 vol% C |

One of the early reports examined densification behavior and characterization [54]. Up to this point, all of the borides examined by ManLabs were densified by hot pressing, but plasma spraying, pressureless sintering, and hot forging were examined as alternative densification methods. The presence of SiC was determined to be beneficial because it not only led to improved oxidation protection, but also inhibited grain growth. The results of oxidation testing were published in a series of manuscripts, including one that is used to justify SiC additions to diborides [55]. Figure 2.8 shows that the oxidation resistance of HfB2–SiC is superior to that of either HfB2 or SiC alone due to the synergistic effects of the borosilicate glassy layer.

Figure 2.8. Oxide-scale thickness as a function of oxidation temperature for HfB2, SiC, and HfB2 containing 20 vol% SiC based on data from Reference [55].

The next report in the series examined the mechanical properties of the boride compositions containing SiC and/or C [56]. For nominally pure diborides, the strength was found to increase from room temperature to a maximum at 800°C. Above 800°C, strength decreased to a minimum at 1400°C and then increased between 1400 and 1800°C (Fig. 2.9). The increase in strength up to 800°C was attributed to the relaxation of thermal residual stresses that were present after processing, but no experimental confirmation was presented to support this assertion. Above 1400°C, the increase in strength was attributed to increasing plasticity, which could act to blunt crack tips. The report also offers detailed explanations and analysis of the effects of grain size and porosity on room and elevated temperature mechanical properties. The addition of SiC was identified as beneficial to mechanical properties by increasing the elevated temperature strength (Fig. 2.10). SiC was found to reduce grain growth during densification as well as improve the strength at elevated temperatures. However, SiC was also found to increase plasticity due to grain boundary sliding, a mechanism that was proposed based on observations of deformation during mechanical testing and supported with compressive creep studies.

Figure 2.9. Strength as a function of temperature for nominally pure ZrB2 (Material I) [56].

Figure 2.10. Strength as a function of SiC content in composition IV (HfB2–SiC) [56].

The last report in this series focused on the thermal, physical, electrical, and optical properties of diborides [57]. In this study, the use of additives was presented as a method for controlling properties, and extensive tables of data for heat capacity, thermal expansion, electrical resistivity, and other properties were presented (Fig. 2.11). For thermal conductivity, the importance of high relative density and minimal impurity contents was discussed.

Figure 2.11. Thermal conductivity of composition I (nominally pure ZrB2) as a function of temperature using two methods, cut bar for temperatures below 1000°C and thermal flash for temperature above 1000°C. The materials were nominally fully dense with a grain size of ~20 µm [57].

The final series of studies at ManLabs focused on evaluating the environmental response of boride-, carbide-, and graphite-based materials. The overall goal was to correlate the behavior of materials in laboratory-based tests (i.e., furnace oxidation termed the material-centric behavior regime in the reports) with tests that simulate hypersonic flight or atmospheric reentry (i.e., relevant conditions referred to as environment-centric in the reports). The final series of studies resulted in the publication of nine reports. The reports began with descriptions of facilities, progressed through tabulating experimental results, and then concluded with an attempt to correlate oxidation response in different test regimes.

The first reports from the final series described the testing methods and facilities that were utilized for the study [58, 59]. The research included conventional furnace oxidation (cold gas/hot wall/low velocity) along with more specialized tests including high-velocity furnace testing (cold gas/hot wall/high velocity) and simulated reentry conditions (hot gas/cold wall/high velocity). To accomplish the testing, specialized furnaces were developed for the high-velocity testing in conventional furnaces (Fig. 2.12). Arc heater facilities at AVCO and other laboratories were also utilized (Fig. 2.13). The facilities, test conditions, temperature measurements, and characterization methods are described in detail in the reports.

Figure 2.12. Schematic of the system built for cold gas/hot wall testing at high gas velocities. The system consisted of an induction heater and high-velocity gas-handling unit [58].

Figure 2.13. Schematic of the 10 MW Arc Splash Facility at AVCO [59].

The second set of reports in the final series focused on experimental results [60, 61]. The materials studied included nominally pure diborides, diboride–SiC composites, carbide–carbon composites, graphite-based materials, and refractory metal-based materials (Table 2.3). For furnace testing below 3800°F (~2100°C), the lowest oxidation rates were measured for composites containing one of the diborides and 20 vol% SiC. Above that temperature, oxidation rates were similar for nominally pure diborides and the diboride–SiC composites due to the depletion of SiC from the composites. Interestingly, carbides exhibited good oxidation protection, but only above about 3450°F (~1900°C). At lower temperatures, the oxide was described as puffy and was not protective. Above 3450°F, the scale was more dense and provided protection to the underlying boride. In all tests, the performance of Hf compounds was slightly better than Zr compounds, presumably due to the higher refractoriness of the HfO2 compared to ZrO2. The temperature limits for oxidation protection for each of the candidate materials are summarized in Figure 2.14.

Table 2.3. Summary of compositions studied for the third series of ManLabs projects

| Designation | Material | Major phase | Composition |

| A-2 | HfB2 | HfB2 | Nominally pure HfB2 |

| A-3 | ZrB2 | ZrB2 | Nominally pure ZrB2 |

| A-7 | HfB2 + SiC | HfB2 | HfB2 plus 20 vol% SiC |

| A-8 | ZrB2 + SiC | ZrB2 | ZrB2 plus 20 vol% SiC |

| A-10 | ZrB2 + SiC + C | ZrB2 | 14 vol% SiC + 30 vol% graphite |

| C-11 | HfC + C | HfC | Graphite (C-Hf hypereutectic) |

| C-12 | ZrC + C | ZrC | Graphite (C-Hf hypereutectic) |

| D-13 | JTA | Graphite | Graphite + 43 wt% ZrB2 + 13 wt% SiC |

| E-14 | KT-SiC | SiC | SiC + ~9 vol% Si |

| F-15 | JT0992 | Graphite | HfC + SiC |

| F-16 | JT0981 | Graphite | ZrC + SiC |

| H-23 | SiO2 + W | SiO2 | SiO2 plus 60 wt% W |

| I-23 | Hf-Ta-Mo | Hf-based alloy | Hf with 20 at% Ta and 2 at% Mo |

Figure 2.14. Summary of the results of furnace kinetic studies based on the recession of the parent material after 2 h. HfB2 is always marginally better than the corresponding ZrB2 composition. Carbides are not good at “moderate temperature, but extend temperature to higher values. JTA = graphite grade with ZrB2 and Si additions. KT-SiC = Si-rich SiC (9 vol% free Si). SiO2 + W = SiO2 + 60 wt% W. JTO992 is C–HfC–SiC and JTO981 is C–ZrC–SiC [60].

To complement the furnace oxidation studies, oxidation behavior was also studied in hot gas/cold wall testing. High heat fluxes were selected to be representative of the conditions that would be encountered during atmospheric reentry. The conditions were severe enough to cause graphite and tungsten to recess on the order of 7–14 in. (~18–36 cm), but resulted in recessions of less than 1 mm in the diboride and carbide materials [61]. Differences were noted in the behavior of materials in conventional furnace oxidation testing, the high-velocity gas flow described in Figure 2.12. The working hypothesis used to explain the results was that different heating methods resulted in different temperature gradients across the oxide scale, which are depicted schematically in Figure 2.15. Specimens in conventional furnace oxidation testing achieve thermal equilibrium. In contrast, the arc heater provides heat to the outside of the specimen, which results in a hotter outside and cooler inside. Likewise, induction heating produces higher temperatures inside the specimen due to generation of heat inside a specimen with an insulating external scale. The materials were tested in a cyclic manner to evaluate the reuse potential (Fig. 2.16). From the tests, the nominally pure diborides and the diboride–SiC composites were identified as the only materials capable of meeting the requirements for the model trajectory. Even though it did not meet the recession criteria established for this project, the merits of JTA graphite (graphite containing a diboride and SiC) also exhibited promising behavior.

Figure 2.15. Schematic description of the temperature gradients observed across the oxide scales for specimens tested in (left) an arc plasma facility that uses hot gas, cold way, and high velocity; (center) conventional tube furnace with low velocity flow; and (right) inductively heated specimen in cold gas/hot wall/high velocity [61].

Figure 2.16. Schematic with information about a model trajectory for a lifting body reentry vehicle showing stagnation pressure and enthalpy along with other information for a vehicle with a 3-in. leading-edge radius [61].

The final reports focused on correlating the behavior observed in material-centered testing in laboratory furnaces with behavior in environment-centered testing that simulated atmospheric reentry conditions [62]. The best success was achieved for describing the behavior of graphite, including the JTA graphite–boride–SiC composite material. For ceramic composites, correlations were more difficult, but some predictive capability was achieved. One of the critical aspects of the research was correlating flight conditions (i.e., altitude and velocity) with test conditions (i.e., enthalpy and heat flux) as shown in Figure 2.17. While the initial goal of correlating behavior in cold gas/hot wall tests in the laboratory to hot gas/cold wall simulations of atmospheric reentry was not met, the project still had significant success by identifying candidate materials for applications. One of the major conclusions of the study was that ZrB2 and HfB2 along with the composites with SiC were the only materials studied that were capable of surviving the extreme environment associated with atmospheric reentry of a sharp leading-edged vehicle.

Figure 2.17. Comparison of measured recession rates (points) as a function of heat flux and total enthalpy. Lines are shown for a calculated surface temperature of 6100°F (3300°C) under two different conditions. The plot also includes a line (– - –) showing the speed and altitude of a potential reentry trajectory [62].

2.4.3 Phase Equilibria

In parallel with the efforts underway at ManLabs, the U.S. Air Force also commissioned a series of studies on phase equilibria in transition metal–based systems. These projects were led by Dr. Edwin Rudy at Aerojet-General Corporation. The overall program resulted in the publication of 38 reports that were broken down into five parts: (1) 14 reports on binary systems, (2) 18 reports on ternary systems, (3) 2 reports on experimental techniques, (4) 3 reports on thermochemical calculations, and (5) a compendium of phase diagram data. Prof. Hans Nowotny from University of Vienna, who remains one of the most prolific authors on transition metal carbide systems, acted as a consultant on the project.

The materials for these projects were produced by the reaction of elemental powders [63]. Starting with high-purity fine powders, the specimens were produced by rapid heating in graphite dies. The total cycle times ranged from 2 to 5 min with a typical heat treating temperature of 1900°C. A pressure of ~39 MPa (380 atm quoted in the report) was applied. After initial reaction, specimens were heat treated at temperatures ranging from 1550 to 1800°C in a W-mesh element furnace. The heat treatments were conducted in sealed tantalum containers under a vacuum of about 7 × 10−3 Pa followed by quenching into a molten tin bath.

Phase diagrams were determined using a modified Pirani-style furnace to melt cylindrical specimens (Fig. 2.18) that was constructed especially for Rudy's experiments [64]. Among the possible designs, the Pirani-style furnace was selected because it allowed for controlled atmosphere, precision measurement of temperature, and elevated temperature while minimizing reactions between the furnace and the specimen. The design used a cylindrical specimen with a thinned center section that had a black body hole that allowed for temperature measurement with a micro-optical pyrometer. This design had the advantage that the hottest temperatures were attained inside the specimen, which enabled more accurate measurement of melting temperatures. To highlight the capabilities of the apparatus, one of the first systems examined was the HfC–TaC binary. A previous study [65] had concluded that a solid solution of HfC and TaC had a higher melting temperature than either end member. Rudy, in an effort to clarify this point, highlighted the capabilities of the system at Aerojet by examining melting temperature across the composition range in this system (Fig. 2.19). Rudy concluded that the melting temperature of Ta-rich compositions was nearly constant across the composition range of interest and did not show a maximum as described by Agte [65]. Interestingly, some researchers continue to disagree on this point.

Figure 2.18. Schematic of the Pirani furnace used for melting point determinations [64].

Figure 2.19. Comparison of melting temperature as a function of composition in the HfC–TaC system for data from Rudy [64] and Agte [65].

The culmination of the phase equilibria studies was an immense volume of data that was compiled at the conclusion of the project [66]. The compendium is more than 700 pages in length and includes data for over 50 binary and 25 ternary systems. Not only does the volume show phase diagrams, but it also includes liquidus projects, three-dimensional images of ternary systems, vertical sections, and isothermal sections in addition to other information that was collected during the project. For example, a tremendous amount of lattice parameter information was analyzed as part of the project and used to construct composition–lattice parameter maps such as the one shown in Figure 2.20. Many of the diagrams produced by Rudy et al., such as the Zr–B–C ternary shown in Figure 2.21, continue to guide researchers working in these materials. These diagrams have been widely reproduced in technical papers and student theses. In addition, Volume X of the Phase Diagrams for Ceramists compilation is devoted to borides, carbides, and nitrides, and features many diagrams from Rudy's work.

Figure 2.20. Lattice parameter as a function of Ta to Ti ratio and carbon content for the TiC–TaC system [66].

Figure 2.21. Liquidus project for the Zr–B–C ternary phase diagram [66].

2.5 Summary

The progression of research on boride-based ultra-high temperature ceramic materials was reviewed. Although boride and carbide ceramics have been studied for over a century, the use of the term ultra-high temperature ceramics is a relatively recent development as this term has become popular only in the past 20 years. For the most part, boride and carbide ceramics remained a scientific curiosity from their first reports in the late 1800s and early 1900s until the 1950s. During the space race, the need for materials that could withstand the extreme environments associated with rocket propulsion, hypersonic flight, and atmospheric reentry became a national priority. Initial studies by NASA identified boride and carbide ceramics as candidates for rocket nozzles based on melting temperatures in excess of 3000°C. In the 1960s, research sponsored by the United States focused on finding materials for reusable atmospheric reentry vehicles with high lift-to-drag ratios. Projections for leading-edge temperatures in excess of 2200°C motivated a series of projects that focused on boride ceramics. Initial screening studies confirmed that not only did these materials possess melting temperatures above 3000°C, but they had also demonstrated resistance to oxidation. Research at ManLabs consisted of three phases that (1) identified HfB2 and ZrB2 as the most promising candidates; (2) studied the processing, microstructure, and properties of ZrB2, HfB2, and their composites with SiC; and (3) evaluated the response of materials to oxidation and exposure to simulated atmospheric reentry conditions. Although the research was not able to correlate performance in laboratory oxidation studies to behavior in high-enthalpy flows, HfB2- and ZrB2-based ceramics were identified as the only materials capable of withstanding the combination of heat flux and surface temperature projected for atmospheric reentry. Parallel studies at Aerojet evaluated the phase equilibria in UHTC systems. An impressive number of binary and ternary phase diagrams resulted from that research, many of which continue to be widely used today.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge funding provided by the Office of Naval Research Global office in London (grant number N62909-12-1-1014 overseen by Dr. Joe Wells) and the European Office of Aerospace Research and Development (grant number FA8655-12-1-0009 overseen by Dr. Randall Pollak) for the conference “Ultra-High Temperature Ceramics: Materials for Extreme Environment Applications II” that was held on May 13–18, 2012, in Hernstein, Austria.

References

- 1. Markovich VI. Boron and Refractory Borides. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1977.

- 2. Jaffe HA. Development and testing of superior nozzle materials. National Aeronautics and Space Administration Final Report for Project NASw-67. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration; April 1961.

- 3. Fenter JR. Refractory diborides as engineering materials. SAMPE Q 1971;2:1–15.

- 4. Storms EK. The Refractory Carbides. New York: Academic Press; 1967.

- 5. Kaufman L, Clougherty EV. Investigation of Boride compounds for very high temperature applications. Air Force Materials Laboratory Report Number RTD-TDR-63-4096, Part II. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH: Air Force Materials Laboratory; February 1965.

- 6. Freeman JW, Cross HC. Notes on heat-resistant materials in Britain from technical mission October 13 to November 30, 1950. National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics Technical Memorandum RM51D23. Washington, DC: National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA); May 14, 1951.

- 7. Samsonov GV. Refractory Transition Metal Compounds; High Temperature Cermets. New York: Academic Press; 1964.

- 8. Schwartzkopf P, Kieffer R, Leszynski W, Benesovsky F. Refractory Hard Metals: Borides, Carbides, Nitrides, and Silicides. New York: Macmillan; 1953.

- 9. U.S. Air Force and National Aeronautics and Space Administration Joint Conference on Manned Hypervelocity and Reentry Vehicles: A Compilation of Papers Presented; NASA-TMX-67563; April 11–12, 1960; Langley Research Center, Langley Field, VA.

- 10. Steurer WH, Crane RM, Gilbert LL, Hermach CA, Scala E, Zeilberger EJ, Raring RH. Thermal Protection Systems: Report on the Aspects of Thermal Protection of Interest to NASA and the Related Materials R&D Requirements. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration; February 1962.

- 11. Loch LD. Above 2500°F: what materials to use? Chem Eng 1958;65 (13):105–109.

- 12. Whittemore OJ Jr. Extreme temperature refractories. J Can Ceram Soc 1959;28:43–48.

- 13. Sata T. Materials for Ultra-High temperature. Oyo Butsuri 1967;36 (7):537–544.

- 14. Noguchi T. Synthesis of Ultrahigh-Temperature ceramic materials. Nippon Kessho Gakkaishi 1974;16 (4):288–293.

- 15. Sata T. Ultra-High temperature materials. Kino Zairyo 1984;4 (1):10–17.

- 16. Tanaka T. Development and problem of Ultra-High temperature materials. Shin Kinzoku Kogyo 1992;348:83–90.

- 17. Hillig WB. Prospects for Ultrahigh-Temperature ceramic composites. In: Tressler RE et al., editors. Tailoring Multiphase and Composite Ceramics. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. p 697–712.

- 18. Vedula KM. Ultra-High temperature ceramic-ceramic composites. Final Report on Project WRDC-TR-89-4089. Wright Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; October 1989.

- 19. Mehrotra GM. Chemical compatibility and oxidation resistance of potential matrix and reinforcement materials in ceramic composites for Ultra-High temperature applications. Final Report Number WRDC-TR-90-4127. Wright Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Systems Command; March 1, 1991.

- 20. Courtright EL, Graham HC, Katz AP, Kerans RJ. Ultra-High temperature assessment study–ceramic matrix composites. Final Report WL-TR-91-4061. Wright Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Wright Laboratory Materials Directorate; September 1992.

- 21. Rasky D, Bull J. Ultra-High temperature ceramics. NASA Report RTOP 232-01-04. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration; May 2, 1994.

- 22. Kolodziej P, Salute J, Keese DL. First flight demonstration of a sharp Ultra-High temperature ceramic nosetip. NASA Technical Report TM-112215. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration; December 1997.

- 23. Kowalski T, Buesking K, Koodziej P, Bull J. A thermostructural analysis of a diboride composite leading edge. NASA Technical Report TM-110407. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration; July 1996.

- 24. Opeka MM, Talmy IG, Wuchina EJ, Zaykoski JA, Causey SJ. Mechanical, thermal, and oxidation properties of refractory Hafnium and Zirconium compounds. J Eur Ceram Soc 1999;19 (13–14):2405–2414.

- 25. Talmy IG, Wuchina EJ, Zaykoski JA, Opeka MM. Ceramics in the system NbB2-CrB2. In: Materials Research Society Symposium Proceedings, Volume 365; November 28–December 2, 1994; Materials Research Society Meeting, Boston, MA. Materials Research Society, Pittsburgh, PA. p 81–87.

- 26. Zhang G-J, Deng Z-Y, Kondo N, Yang J-F, Ohji T. Reactive hot pressing of ZrB2–SiC composites. J Am Ceram Soc 2000;83 (9):2330–2332.

- 27. Tucker SA, Moody HR. The preparation of a new metal Boride. Proc Chem Soc Lond 1901; 17 (238):129–130.

- 28. Tucker SA, Moody HR. The preparation of some new metal Borides. J Chem Soc 1902;81:14–17.

- 29. McKenna PM. Tantalum carbide: its relation to other hard refractory compounds. Ind Eng Chem 1936;28 (7):767–772.

- 30. Agte C, Moers K. Methoden zur Reindarstellung hochschmelzender Carbide, Nitride und Boride und Beschreibung einiger ihrer Eigenschaften. Z Anorg Allg Chem 1931;198 (1):233–275.

- 31. Acheson EG. Article of carborundum and process of the manufacture thereof. US patent 645648. 1898.

- 32. Moissan H. Volatilisation of Zirconia and Silica at a high temperature and their reduction by carbon. C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci 1894;116:1222–1224.

- 33. Moissan H. Preparation of tungsten, molybdenum, and vanadium in the electric arc furnace. C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci 1894;116:1225–1227.

- 34. Moissan H. Titanium. C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci 1895;120:290–296.

- 35. Moissan H. A new zirconium carbide. C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci 1896;122:651–654.

- 36. Samsonov GV. Continuous-discrete character of variation of the type of bonding in refractory compounds of transition metals and principles of classification of refractory compounds. In: Samsonov GV, editor. Refractory Transition Metal Compounds; High Temperature Cermets. Academic Press: New York; 1964. p 1–12.

- 37. Samsonov GV, Sinel'nikova VS. Electrical resistance of refractory compounds at high temperatures. In: Samsonov GV, editor. Refractory Transition Metal Compounds; High Temperature Cermets. Academic Press: New York; 1964. p 172–177.

- 38. Kiessling R. The borides of some transition metals. Acta Chem Scand 1995;4:209–227.

- 39. Heppenheimer TA. The Space Shuttle Decision: NASA's Search for a Reusable Space Vehicle. Washington (DC): The National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 1999.

- 40. Hallion RP. The NACA, NASA, and the supersonic-hypersonic frontier. In: Dick SJ, editor. NASA's First 50 Years. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington (DC); 2010. p 223–274.

- 41. Love ES. Introductory considerations of manned reentry orbital vehicles. U.S. Air Force and National Aeronautics and Space Administration Joint Conference on Manned Hypervelocity and Reentry Vehicles: A Compilation of Papers Presented; April 11–12, 1960, NASA Report TMX 67563. Langley Field (VA): Langley Research Center. p 39–54.

- 42. Mathauser EE. Materials for application to manned reentry vehicles. U.S. Air Force and National Aeronautics and Space Administration Joint Conference on Manned Hypervelocity and Reentry Vehicles: A Compilation of Papers Presented; April 11–12, 1960, NASA Report TMX 67563. Langley Field (VA): Langley Research Center. p 559–570.

- 43. Schick HL. Thermodynamics of Certain Refractory Compounds: Thermodynamic Tables, Bibliography, and Property File. New York: Academic Press; 1966.

- 44. Chase MW Jr. Zirconium diboride. In: NIST-JANAF Thermochemical Tables, Fourth Edition, Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, Monograph Number 9. Woodbury (NY): American Chemical Society and American Institute of Physics; 1998. p 279.

- 45. McClaine LA. Thermodynamic and kinetic studies for a refractory materials program. Technical Report ASD-TDR-62-204. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; April 1964.

- 46. Kuriakose AK, Margrave JL. The oxidation kinetics of zirconium diboride and zirconium carbide at high temperatures. J Electrochem Soc 1966;111 (7):827–831.

- 47. Berkowitz-Mattuck JB. High-temperature oxidation III. zirconium and hafnium diborides. J Electrochem Soc 1966;113 (9):908–914.

- 48. Berkowitz-Mattuck JB. Kinetics of oxidation of refractory metals and alloys at 1000°C-2000°C. ASD-TDR-62-203. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Aeronautical Systems Division; March 1963.

- 49. Domalski ES, Armstrong GT. Heats of formation of metallic borides by fluorine bomb calorimetry. Technical Report APL-TDR-64-39. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): U.S. Air Force Aeropropulsion Laboratory; March 1964.

- 50. Janowski KR, Carnahan RD, Rossi RC. Static and dynamic oxidation of ZrC. SSD-TR-66-33. Los Angeles (CA): Ballistic Systems and Space Systems Division, Air Force Systems Command; January 1966.

- 51. Kibler GM, Lyon TF, Linevsky MJ, DeSantis VJ. Refractory materials research. WADD-TR-60-646. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; August 1964.

- 52. Kaufman L. Investigation of boride compounds for very high temperature applications. Report Number RTD-TDR-63-4096, Part I. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; December 1963.

- 53. Kaufman L, Clougherty EV. Investigation of boride compounds for very high temperature applications. Report Number RTD-TDR-63-4096, Part II. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; February 1965.

- 54. Clougherty EV, Hill RJ, Rhodes WJ, Peters ET. Research and development of refractory oxidation-resistant diborides part II, volume II: processing and characterization. Technical Report AFML-TR-68-190. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; January 1970.

- 55. Clougherty EV, Pober RL, Kaufman L. Synthesis of oxidation resistant metal diboride composites. Trans Metallurgical Society AIME 1968;242 (6):1077–1082.

- 56. Rhodes WH, Clougherty EV, Kalish D. Research and development of refractory oxidation-resistant diborides part II, volume IV: mechanical properties. Technical Report AFML-TR-68-190. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; November 1969.

- 57. Clougherty EV, Wilkes KE, Tye RP. Research and development of refractory oxidation-resistant diborides part II, volume V: thermal, physical, electrical, and optical properties. Technical Report AFML-TR-68-190. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; November 1969.

- 58. Kaufman L, Nesor H. Stability characterization of refractory materials under high velocity atmospheric flight conditions part II, volume II: facilities and techniques employed for cold gas/hot wall tests. Technical Report AFML-TR-69-84. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; December 1969.

- 59. Kauman L, Nesor H. Stability characterization of refractory materials under high velocity atmospheric flight conditions part II, volume III: facilities and techniques employed for hot gas/gold wall tests. Technical Report AFML-TR-69-84. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; December 1969.

- 60. Kaufman L, Nesor H. Stability characterization of refractory materials under high velocity atmospheric flight conditions part III, volume I: experimental results of low velocity cold gas/hot wall tests. Technical Report AFML-TR-69-84. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; December 1969.

- 61. Kaufman L, Nesor H. Stability characterization of refractory materials under high velocity atmospheric flight conditions part III, volume III: experimental results of high velocity hot gas/cold wall tests. Technical Report AFML-TR-69-84. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; February 1970.

- 62. Kaufman L, Nesor H, Bernstein H, Baron JR. Stability characterization of refractory materials under high velocity atmospheric flight conditions part IV, volume I: theoretical correlation of material performance with stream conditions. Technical Report AFML-TR-69-84. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; December 1969.

- 63. Rudy E, Windisch S, Chang YA. Ternary phase equilibria in transition metal-boron-carbon-silicon systems: part I. related binary systems, volume I. Mo-C System. Technical Report AFML-TR-65-2. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; January 1965.

- 64. Rudy E, Progulski G. Ternary phase equilibria in transition metal-boron-carbon-silicon systems: part III. Special techniques, volume II. A pirani-furnace for precision determination of melting temperatures of refractory metallic substances. Technical Report AFML-TR-65-2. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; May 1967.

- 65. Agte C, Alterthum H. Systems of high-melting carbides; Contributions to the problem of carbon fusion. Z Tech Phys 1930;11:182–191.

- 66. Rudy E. Ternary phase equilibria in transition metal-boron-carbon-silicon systems: part V. Compendium of phase diagram data. Technical Report AFML-TR-65-2. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (OH): Air Force Materials Laboratory; May 1969.