3

Reactive Processes for Diboride-Based Ultra-High Temperature Ceramics

Guo-Jun Zhang, Hai-Tao Liu, Wen-Wen Wua, Ji Zoua, De-Wei Nia, Wei-Ming Guoa, Ji-Xuan Liu and Xin-Gang Wang

State Key Laboratory of High Performance Ceramics and Superfine Microstructure, Shanghai Institute of Ceramics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China

3.1 Introduction

From the standpoint of material flow, the life cycle of diboride-based Ultra-High temperature ceramics (UHTCs) consists of two parts: fabrication and application (Fig. 3.1).

Figure 3.1. The life cycle of diboride-based ceramics.

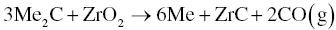

During fabrication, transition metal oxides (MeO2, such as ZrO2 and HfO2) or elemental metals (Me, such as Zr and Hf) are combined with boron sources (B, B2O3, B4C, etc.) to synthesize transition metal diboride (MeB2, such as ZrB2 and HfB2) powders. Subsequently, MeB2 powders are densified using methods such as pressureless sintering (PLS), hot pressing (HP), or spark plasma sintering (SPS), to obtain the final UHTC components. When using MeO2, the synthesis of diborides includes reduction from Me4+(O2−)2 to Me2+(B−)2. In contrast, when using elemental metals, oxidation from Me0 to Me2+(B−)2 is required. Powder synthesis and densification can be combined to fabricate final UHTC products in one step by processes such as reactive sintering. Reactive HP (RHP) and reactive spark plasma sintering (R-SPS) are two examples of this technique.

On the other hand, in the application process, UHTCs are used in environments that are rich in oxygen at high temperature. Some examples include sharp noses and leading edges for atmospheric reentry and hypersonic vehicles, or the corrosive environments of acids, alkalis, and molten metals. During application, especially at high temperature, MeB2 can be oxidized under ablation conditions, leaving products of MeO2 and gaseous B2O3. In some respects, the application process is the opposite of the reduction reactions used in fabrication. In view of this, the life cycle for diboride-based UHTCs can be summarized as a reduction–oxidation reaction cycle, with material flow from MeO2 (or Me) → Fabrication → MeB2 → Application → MeO2.

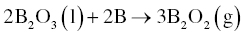

Both the fabrication and application processes involve chemical reactions, so chemical reactions play important roles during the entire diboride-based UHTC life cycle. In this chapter, discussion of reactive processes is limited to the fabrication process where reduction reactions dominated, but some oxidations reactions are used to convert Me to MeB2. In contrast, oxidation reactions that occur during application are not included. The discussion of reactive processes focuses on (i) synthesis of MeB2 powders by different chemical reactions in Section 3.2, (ii) oxygen removal reactions for sintering UHTCs when using MeB2 as starting materials in Section 3.3, and finally (iii) reactive sintering processes to fabricate UHTCs in a combined synthesis and densification process in Section 3.4. A roadmap for the fabrication of MeB2 is shown in Figure 3.2. In addition, thermodynamic aspects of the main reactions in Figure 3.2, including the temperatures at which the reactions become favorable at standard state and under mild vacuum, are shown in Table 3.1.

Figure 3.2. Roadmap of the fabrication process of MeB2 discussed in this chapter.

Table 3.1. Thermodynamics of the main reactions including the temperatures at which the reactions become favorable at standard state and under mild vacuum

| Reaction number in this chapter | Reaction | Type of process | Enthalpy ΔHo298 (kJ) | Free enthalpy ΔGo298 (kJ) | Minimum favorable temperature at standard state (°C) | Minimum favorable temperature with pCO = 15 Pa (°C) |

| (3.1) | Zr + 2B = ZrB2 | Elemental reaction/ reactive sintering | −322.586 | −318.102 | ΔG < 0 (R.T.—2000°C) | ΔG < 0 (R.T.—2000°C) |

| (3.2) | ZrO2 + B2O3 + 5C = ZrB2 + 5CO(g) | Carbothermal reduction/oxygen removing | 1496.907 | 1231.202 | 1140 | 775 |

| (3.3) | 2ZrO2 + B4C + 3C = 2ZrB2 + 4CO(g) | Carbo/borothermal reduction/oxygen removing | 1175.262 | 961.366 | 1428 | 911 |

| (3.10) | 3ZrO2 + 10B = 3ZrB2 + 2B2O3 (g) | Borothermal reduction/oxygen removing | 661.141 | 522.426 | 1275 | 849 |

| (3.5) | 7ZrO2 + 5B4C = 7ZrB2 + 3B2O3 + 5CO (g) | Boron carbide reduction/oxygen removing | 1385.588 | 1113.223 | 1219 | 797 |

| (3.16) | ZrO2 + 3WC = ZrC + 3W + 2CO (g) | Oxygen removing | 803.069 | 690.083 | 1944 | 1298 |

| (3.23) | 2Zr + B4C + Si = 2ZrB2 + SiC | Reactive sintering | −655.075 | −644.364 | ΔG < 0 (R.T.—2000°C) | ΔG < 0 (R.T.—2000°C) |

3.2 Reactive Processes for the Synthesis of Diboride Powders

Diboride powders can be synthesized by different approaches that can be divided into three main groups: (1) elemental reactions between Me and B, (2) reduction processes using MeO2, and (3) chemical routes from polymeric precursors. Chemical routes used to synthesize borides include solutions, reactions with boron-containing polymers, and pre-ceramic polymers. None of these will be discussed in this chapter. This section describes elemental reactions between Me and B and reduction processes using MeO2 as starting reactants.

For elemental reactions, diboride powders are synthesized from elemental metals (Me) or metal hydrides (MeH2) and boron. For reduction processes, transition metal oxides, MeO2, are usually used as the metal source and boron-containing materials, such as B or B4C or B2O3, are used as the boron source. Some of the boron sources can also act as reducing agents, specifically B and B4C. In some cases, reducing boron sources are combined with carbon. To prevent oxidation of the powders, reductions can be performed under vacuum or inert atmospheres. During the reduction process, two factors to consider are as follows:

- Loss and compensation of boron. In reduction processes, gaseous species, such as B2O3 (g), may form during the process, which results in the loss of boron source from the powder mixture. Therefore, excess boron is typically added to the raw materials to compensate for any boron loss. Evaporation of boron-containing gaseous species is affected by the synthesis conditions (e.g., gas pressure in the chamber, synthesis temperature, and heating rate), so the amount of the excess boron source is not predictable.

- The balance between purity and grain size. The starting materials unavoidably contain impurities. In addition, if the MeO2 used in reduction processes is not completely consumed, it will remain in the final powders as oxygen impurities. Higher synthesis temperatures can remove impurities, such as B2O3, which evaporate at higher temperature. On the other hand, higher temperatures lead to increased grain growth, which is contrary to the desire for finer powders. So the interplay between the purity and the grain size should be considered. One approach to balance them is to choose appropriate synthesis temperatures and holding times to prepare high purity and superfine MeB2 powders.

This chapter discusses MeB2 synthesis by carbothermal reduction, borothermal reduction, boron carbide reduction, and carbo/borothermal reduction. Among all of the processes for MeB2 synthesis, these are the most popular and economical methods, so they are used most often.

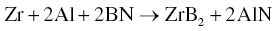

3.2.1 Elemental Reactions

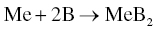

Elemental reactions such as those shown in Reaction 3.1 are the simplest process for MeB2 powder synthesis and have been used for the longest time. These reactions are highly exothermic ( = −318 kJ for ZrB2 and −325 kJ for HfB2), so self-propagating reactions between the precursors can be ignited. These reactions generate large quantities of heat and can promote local melting of the transition metal, which further accelerates the reaction. Elemental reactions are beneficial for self-propagating high-temperature synthesis because the high heating and cooling rates can produce high defect concentrations in as-synthesized powders, which can improve subsequent densification.

= −318 kJ for ZrB2 and −325 kJ for HfB2), so self-propagating reactions between the precursors can be ignited. These reactions generate large quantities of heat and can promote local melting of the transition metal, which further accelerates the reaction. Elemental reactions are beneficial for self-propagating high-temperature synthesis because the high heating and cooling rates can produce high defect concentrations in as-synthesized powders, which can improve subsequent densification.

3.2.2 Reduction Processes

3.2.2.1 Carbothermal Reduction.

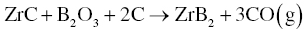

Reaction 3.2 is a carbothermal reduction reaction that is commonly used to synthesize MeB2 powders. However, the volatility of B2O3 can result in substantial loss of B2O3 (10–30 wt%), which requires addition of excess B2O3 during the synthesis process. A balance exists between formation of borides and evaporation of B2O3, and, under the right conditions, the rate of reduction of MeO2 and B2O3 can exceed the rate of evaporation of B2O3. Minimizing carbon contamination is another factor to consider. For the synthesis of ZrB2, Karasev [1] observed opposite trends for B and C content in the final powders based on the addition of excess B2O3. For an excess of B2O3 in the range of 10–30 wt%, the reduction rate of ZrO2 and B2O3 exceeded the B2O3 evaporation rate. This resulted in a stoichiometric powder composition with a C concentration of less than 1 wt%. When the B2O3 excess increased to the range of 80–200 wt%, the rate of evaporation of B2O3 grew, resulting in a higher concentration of C in the final powder. Increasing the excess B2O3 concentration further to 300–400 wt% enabled ZrB2 to be produced with less C. Unfortunately, using large excesses of B2O3 is not economical. Commercially, synthesis of ZrB2 typically uses an excess B2O3 content of 10–30 wt%, which results in pure ZrB2 powders with low C contents. Although Karasev synthesized powders at 2000°C, ZrB2 powders can be produced at lower temperatures (e.g., ~1500°C).

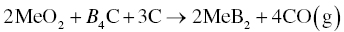

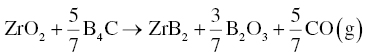

3.2.2.2 Carbo/Borothermal Reduction.

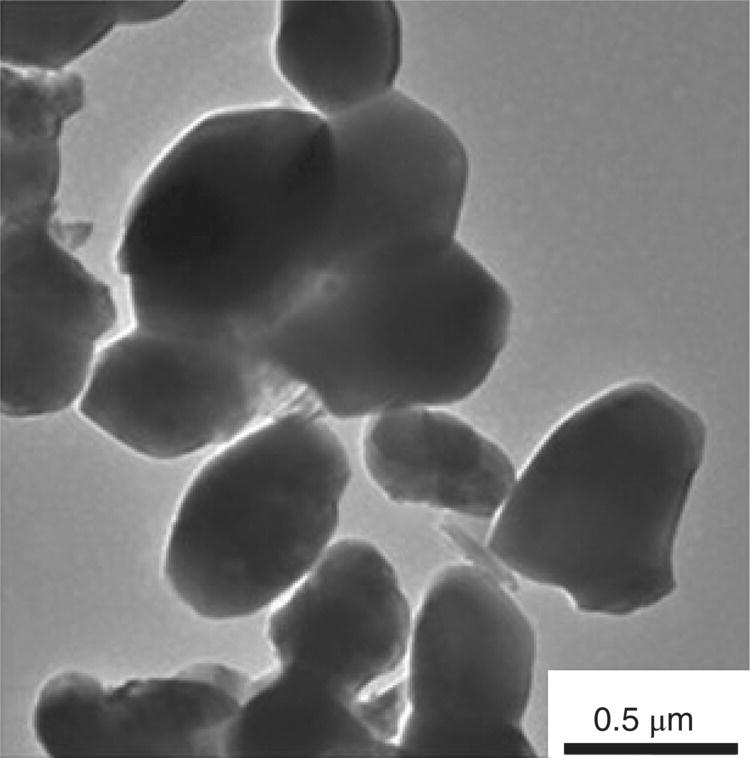

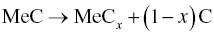

Another method used to synthesize MeB2 powders uses MeO2 as the transition metal source and B4C as the boron source (Reaction 3.3) [2, 3], which may not occur in one step [4] based on thermodynamic calculations showing that some intermediate reactions may be more favorable (Fig. 3.3). From the thermodynamic calculations, Reactions 3.4 and 3.2 are likely intermediate steps for the overall processes described in Reaction 3.3.

Figure 3.3. Standard free energy of reactions as a function of temperature [4].

The analysis summarized in Figure 3.1 suggests that Reaction 3.4 is predominant below 1540°C, while above 1540°C, Reaction 3.2 is more favorable.

Several reports have proposed another possible intermediate process as shown in Reaction 3.5 [4, 5], which may take place before Reactions 3.4 or 3.2.

Some phases, such as carbon, are both a reactant and an intermediate product, indicating that intermediate reactions may take place simultaneously.

Both thermodynamic calculations and experiments demonstrate that the overall synthesis process (Reaction 3.3) goes to completion only above 1500°C. Further, the loss of B2O3 at the synthesis temperature affects the overall process and can result in the formation of ZrC in the final products by Reaction 3.6.

One method to eliminate ZrC formation is to utilize excess B4C. The presence of C in B4C means that the amount of carbon could be decreased. Guo et al. [5] used 20–25 wt% excess B4C to produce nominally pure ZrB2 after 1 h at 1650–1750°C. Even if ZrC forms as an intermediate product, it can be removed in the presence of excess B2O3 by Reaction 3.7 at temperatures above 1650°C.

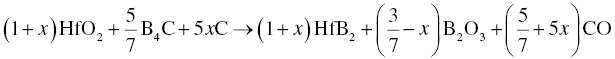

Similarly, fine HfB2 powders can also be obtained by Reaction 3.8 at 1500–1600°C for 1–2 h [6].

where x can vary from 0 to 3/7. When x = 3/7, Reaction 3.8 reduces to Reaction 3.3, meaning that Reaction 3.3 is a special case of Reaction 3.8. In practice, setting x to different values can produce high purity, fine HfB2 powders with a quasi-columnar morphology. The best synthesis conditions seem to be for 0 ≤ x ≤ 1/4 together with 0–10 wt% excess B4C and 0–15 wt% excess carbon.

3.2.2.3 Borothermal Reduction.

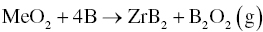

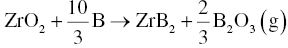

Carbon is used in both carbothermal and carbo/borothermal reduction. The problem with both processes is that carbon may remain in the final products as an impurity. The use of elemental B as raw material to synthesize MeB2 by borothermal reduction could minimize or eliminate carbide or carbon impurities. Common borothermal processes are shown as Reactions 3.9 and 3.10 [7, 8].

During reaction, detection of and discrimination between different boron oxides are difficult. As a result, potential vapor species are typically identified by simulation from thermodynamic calculations. For the reaction of 1 mol ZrO2 and 4 mol B, a probable reaction path is that Reaction 3.10 would take place first, followed by the reaction of excess B (i.e., 0.67 mol based on 4 mol for Reaction 3.9 less 3.33 mol for Reaction 3.10) with B2O3(l) to form boron-rich gaseous species such as B2O2 (g) and BO (g) by processes such as those described by Reactions 3.11 and 3.12.

In contrast to carbo/borothermal reduction, B2O3 is not an intermediate phase, but a final product in borothermal reduction. Hence, the starting B can be consumed by reaction with B2O3. Experimental studies have shown that a ZrO2/B molar ratio in the range of 3.33–4 is appropriate to synthesize ZrB2. Although carbon impurities are avoided in this carbon-free reaction, boron oxides are formed and will be the main source of oxygen impurities. The retained B2O3 can be removed by washing with hot water or vaporization at 1500°C or higher with the latter thought to be more effective at producing a pure product. Fine HfB2 powders have also been obtained by the same method [9].

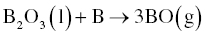

With respect to the final particle size, higher temperatures lead to coarsening. Guo et al. [10] reported a two-step process that included an intermediate water washing (RWR) step that included the following: (i) borothermal reduction at approximately 1000°C to obtain a mixture of ZrB2 powder and boron oxide, (ii) water washing to remove the oxide, and then (iii) a second reduction stage at 1550°C to remove residual oxygen. Particle coarsening was effectively restrained by the intermediate water washing process, resulting in pure, submicrometer ZrB2 powders with low levels of oxygen impurities (Fig. 3.4).

Figure 3.4. TEM image of the submicrometer ZrB2 powder by RWR [10].

3.2.2.4 Boron Carbide Reduction.

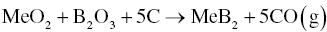

Boron carbide reduction is another approach to produce transition metal diborides. Using ZrB2 as an example, Reaction 3.5 indicates that ZrO2 will react with B4C to form ZrB2 plus gaseous oxides [11]. Zou et al. [11] compared ZrB2 powders synthesized by three different approaches under vacuum at 1600°C for 1.5 h, which are summarized as Reactions 3.3, 3.5, and 3.9. The particle size (~1.0 µm) from Reaction 3.5 was larger than that produced by 3.3 (~0.85 µm), but smaller than Reaction 3.9 (~1.6 µm). The carbon impurity level for Reaction 3.5 was lower than Reaction 3.3. Further, Reaction 3.5 resulted in the lowest oxygen impurity levels, with an oxygen content of only 0.46 wt% compared with 0.51 wt% for Reaction 3.3 and 1.02 wt% for Reaction 3.9. Furthermore, Reaction 3.5 can take place at lower temperatures than Reaction 3.3. However, the composition must be controlled to avoid Reaction 3.4 instead of Reaction 3.5 since the latter produces carbon as an impurity in the as-synthesized powders.

3.2.3 Synthesis of Composite Powders

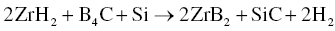

In practice, MeB2 is usually produced with other phases, such as SiC, to form composites. The second phase can promote densification and improve properties of the composites. MeB2-based composite powders can be prepared by reaction synthesis. One example is combustion synthesis of ZrB2–SiC–ZrC composite powders by combustion in air according to Reaction 3.13 [12].

Using a mixture of Zr, B4C, and Si as starting materials, ZrB2-based composite powders with different ZrC contents can be synthesized by varying x. No combustion occurred under vacuum, but in air, the combustion reaction ignited easily. The heat generated from Reaction 3.13 was not sufficient for combustion under vacuum. In contrast, when reacted in air, Zr first reacted with oxygen to form ZrO2, providing sufficient heat to ignite combustion with B4C and Si. Although the reaction was done in air, the final composite powders were homogeneous, fine particles less than 1 µm in size with low oxygen content.

In summary, powder synthesis is an important part of the life cycle and should be designed based on the desired properties of the as-synthesized MeB2 powders. Characteristics such as purity, particle size, and morphology affect densification and microstructure of the final ceramics. Dense UHTCs with finer grain sizes have superior mechanical properties at both room and elevated temperatures [13].

3.3 Reactive Processes for Oxygen Removing during Sintering

The strong covalent bonding and low-volume self-diffusion coefficients of MeB2 phases make densification difficult. Usually, diboride UHTC are prepared by densification methods, such as RHP, HP, and SPS. Additives, such as SiC, MoSi2, Si3N4, B4C, and C, are required for processes such as PLS. Oxygen impurities, which are always present on the surfaces of nonoxide ceramic powders, have a negative effect on the densification for diboride-based UHTCs.

While it is possible to sinter ZrB2 to full density if the starting particle sizes are small enough, the synthesis conditions required are not economical for commercial processes. Therefore, post-synthesis particle size reduction processes are commonly used. Ball milling is an effective treatment method to obtain finer powders, which increases the driving force for densification due to higher surface area and the presence of defects induced by grinding. At the same time, oxygen impurity content increases during the milling process. Oxygen contamination takes the form of MeO2 and B2O3 on the particle surfaces as oxygen has very limited solubility in the MeB2 lattice. Sintering of MeB2 is inhibited by the presence of B2O3 and MeO2, because oxygen impurities promote coarsening mechanisms, which reduces surface area and the driving force for sintering [14].

Boron oxide can be removed from MeB2 particle surfaces by evaporation at elevated temperatures according to Reaction 3.14.

Zhang et al. [15] studied the vapor pressure as a function of temperature using thermodynamic calculations (Fig. 3.5), indicating that B2O3 can be removed under mild vacuum at elevated temperatures.

Figure 3.5. Calculated vapor pressure of B2O3 as a function of temperature in the pressure range maintained in the sintering furnace [15].

In contrast, MeO2 impurities are more difficult to remove. Thermal treatments alone are not sufficient to vaporize MeO2. As a result, MeO2 impurities are typically removed using reducing additives as sintering aids. In general, the criteria for the selection of sintering aids for MeB2 include the following: (i) must facilitate removal of MeO2 and (ii) must form only volatile or high-melting-temperature phases [15]. In this section, some examples of reactive processes for removing oxygen during the sintering of MeB2-based UHTCs are discussed.

3.3.1 Oxygen Removal by Reduction Using Boron/Carbon-Containing Compounds

Because MeO2 is one of the main oxygen impurities in MeB2 powders, the reactions used for synthesizing MeB2 powders from MeO2 can also be used to remove oxygen. As a result, B, B4C, and C are all effective sintering aids.

3.3.1.1 Boron.

Boron can be used to synthesize MeB2 powders by Reaction 3.15 [16, 17].

Hence, B can also be used as a sintering aid to remove MeO2 impurities. Boron is more effective for PLS processes, since B2O3 that is formed is more difficult to remove by evaporation during pressure-assisted sintering.

Typically, around 1 wt% boron is used to promote densification. Lower amounts (≤0.5 wt%) may not be enough to remove the oxide impurities, whereas excess boron (≥2 wt%) can form a liquid phase at above 2100°C (the melting point of boron is about 2092°C). Any boron liquid phase would promote rapid grain growth in the MeB2, which is detrimental to densification.

3.3.1.2 Boron Carbide.

Boron carbide is also a potential sintering aid for MeB2 based on the removal of oxygen by processes similar to Reaction 3.5 [15, 18–21]. Both thermodynamic calculations and experimental results indicate that the reaction can proceed at temperatures in the ranges of 1200°C–1450°C. The addition of B4C enables densification in MeB2 by facilitating the removal of MeO2 at temperatures low enough to prevent significant coarsening of the MeB2 before densification mechanisms become active. B4C is an ideal sintering aid for MeB2 as it reacts with MeO2 to form MeB2. Furthermore, excess B4C can pin grain growth during sintering, resulting in a finer grain size in the final ceramics.

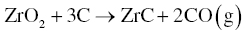

3.3.1.3 Carbon.

Carbon removed oxygen from MeB2 particle surfaces by classic carbothermal reduction, which is also used to synthesize MeB2 powders (Reaction 3.2) [22, 23]. Zhu et al. [22] coated carbon onto ZrB2 particle surfaces to densify ZrB2. Reactions between the C coating and surface oxides on ZrB2 particles were proposed to include carbothermal reduction by Reaction 3.2. Any loss of B2O3 would result in excess of ZrO2, which could lead to ZrC formation by Reaction 3.6. Removal of oxides should minimize coarsening of ZrB2 and consequently promote densification.

3.3.1.4 Boron Carbide and Carbon.

Compared with a single additive, a combination of additives can have a synergistic effect on densification. In particular, the combination of B4C and carbon [24–26] has been used to effectively densify ZrB2. Reaction 3.5 is thought to be the main reaction responsible for MeO2 removal when MeB2 is sintered with B4C alone. However, this reaction leads to the formation of liquid B2O3, which can promote grain coarsening. Analysis of Reactions 3.2 and 3.3 indicates that both ZrO2 and liquid B2O3 can be removed by reaction with carbon. Thus, the combination of C and B4C may facilitate oxide removal more effectively than either additive alone.

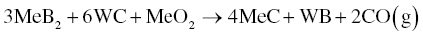

3.3.2 Oxygen Removing by Transition Metal Carbides

In addition to reactions with B, B4C, and C, Chamberlain et al. discovered that WC is an effective reductant for oxygen impurities in MeB2 [27]. Then, Zou et al. revealed that other transition metal carbides can remove oxygen [28].

3.3.2.1 Tungsten Carbide.

In the presence of WC, the products with MeO2 are MeC and W (Reaction 3.16), which are both solid phases with very high melting points. The other product, CO, can be removed as a gas.

Zhang et al. [15] revealed that an intermediate phase, W2C, could be formed during sintering and also facilitate oxygen removal by Reactions 3.17 and 3.18.

In addition to Reaction 3.16, Zou et al. [29, 30] revealed that another reaction with the MeB2 matrix, the MeO2 impurity, and WC was possible (Reaction 3.19).

Experiment results show that this reaction can take place at temperature as low as 1450°C. In this case, the impurity phase, MeO2, could also serve as a reaction promoter, which decreased the temperature at which the reaction became favorable and accelerated the reaction between WC and MeB2 [31].

Solid solutions can form between the matrix and additives. Compared with Zr, W has a smaller covalent radius (1.57Å for Zr and 1.38Å for W) and goes into ZrB2 crystal lattice to form a solid solution. Likewise, C (0.84Å) can substitute onto B (0.93Å) lattice positions, also forming solid solutions. Incorporation of C and W into ZrB2 produces electron deficiencies and/or lattice vacancies. These defects increase densification rates by decreasing activation energies and increasing solid-state diffusion rates, which could be another mechanism for the enhancement of densification by WC in addition to oxygen removal [27, 32]. However, the temperatures for oxygen removal by WC are proposed to be more than 1850°C [15, 26], which are higher than other additives such as B, B4C, and C. Finally, WC has other significant impacts on ZrB2 properties, such as flexural strength, especially at temperatures above 1000°C.

3.3.2.2 Other Transition Metal Carbides.

Besides WC, a number of other transition metal carbides (MeC) have high melting points. Zou et al. [28, 33, 34] performed a systematic study of the effect of MeC additions on the densification behavior of ZrB2–SiC ceramics. The transition metal carbides investigated were VC, TaC, TiC, NbC, and HfC, as well as WC.

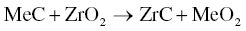

First, thermodynamic predictions showed that MeC should react with ZrO2; however, the reactions and the resulting products are different depending on the transition metal carbide, as shown in Figure 3.6.

Figure 3.6. Molar content of the products calculated by reactions between 3 mole MeC and 1 mole ZrO2 as a function of the temperature at a vacuum level of 5 Pa: (a) WC, (b) VC, (c) NbC, (d) TiC,(e) TaC, and (f) HfC [28].

WC and VC remove oxygen in the same way, as discussed earlier. Intermediate phases form after the dissociation of MeC during heating by Reaction 3.20, where x can vary between 0 and 1 and Me can be W, V, Nb, or Ta.

Most of the MeO2 can be removed below 1650°C by the successive reactions with C or Me2C formed by reaction. For NbC and TaC, the formation of NbCx and TaCx becomes favorable during heating, and ZrO2 can react with carbon, which is released by decomposition of NbC and TaC. However, subsequent reactions between residual ZrO2 and the newly formed NbCx or TaCx are not favorable, namely, Reaction 3.21 is not available for Nb or Ta. As a result, some residual ZrO2 exists in the final products.

For TiC and HfC, an exchange reaction occurs between the carbide and ZrO2 (Reaction 3.22) rather than oxygen removal.

Experimental results confirmed thermodynamic predictions of the ability to react with surface oxides and remove oxygen impurities in the following order:

The sequence is a guide for selecting transition metal carbides as sintering aids for MeB2 ceramics based on their ability to react with and remove oxide impurities.

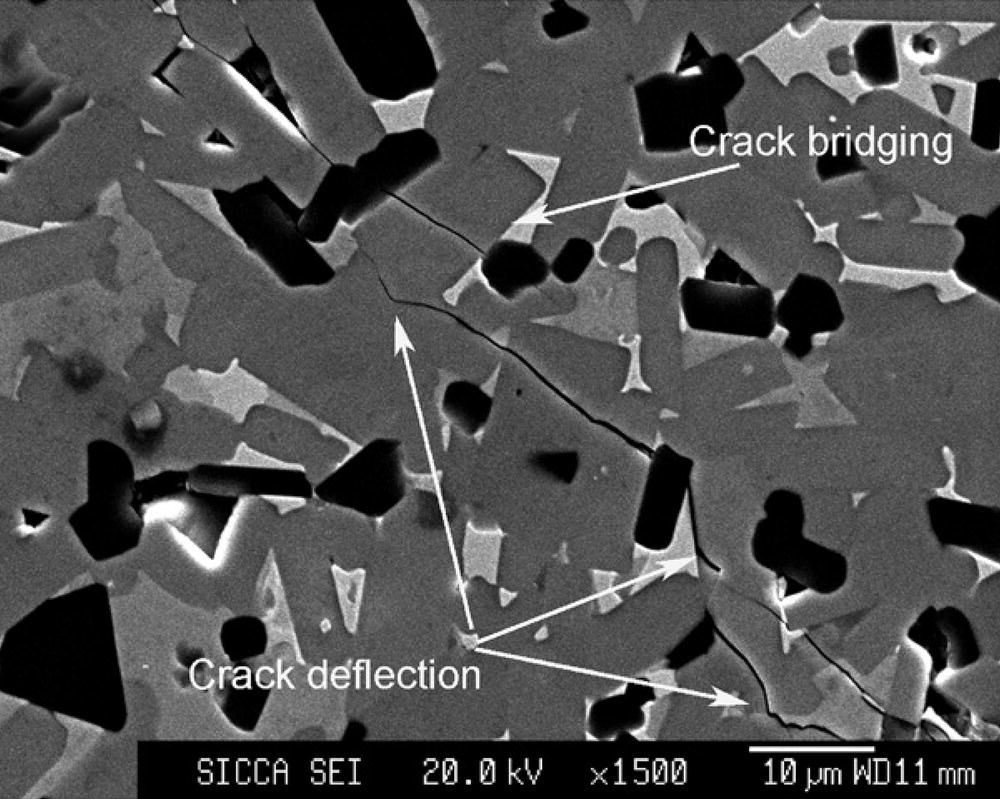

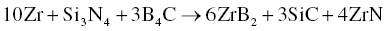

In summary, densification of diboride-based UHTCs requires oxygen impurity levels that are as low as possible. Oxygen removal by reaction with reducing agents can promote densification and can have beneficial effects on the mechanical properties of the resulting ceramics. Furthermore, additives can help tailor microstructures and improve properties. An interesting example is the ZrB2–SiC–WC composites prepared by Zou et al. In this study, the ZrB2 starting powders were synthesized by solid-state reduction, and WC was used as a sintering aid. Nearly fully dense ceramics were obtained, and they demonstrated high fracture toughness and room temperature strength. The improved densification and properties were attributed to the presence of WC, which promoted anisotropic growth of ZrB2 grains and produced a platelet morphology with an interlocking microstructure (Fig. 3.7) [29]. Further, ZrB2–SiC–WC retained a strength of at least 675 MPa at temperatures as high as 1600°C, exhibiting elastic, transgranular fracture (Fig. 3.8). This is one example of the benefits that oxygen removal has on MeB2 UHTCs [35].

Figure 3.7. SEM images of indentation crack propagation in ZrB2–SiC–WC ceramics by Zou et al. [29]

Figure 3.8. (a) The flexural strength of ZrB2–SiC (ZS), ZrB2–SiC–WC (ZSW), and ZrB2–SiC–ZrC (ZSZ) as a function of testing temperature, (b) the load–displacement curves for ZS, ZSW, and ZSZ at 1600°C [35].

3.4 Reactive Sintering Processes

Reactive sintering, which combines synthesis and densification, can produce dense ceramics from high-purity powders in a single thermodynamically favorable in situ step [36–39]. Compared with conventional sintering, some advantages of reactive sintering processes and reaction sintered ceramics are as follows:

- Reactive sintering can produce dense UHTCs at a lower temperature (usually ≤1800°C). Chemical reactions during reactive sintering are highly exothermic and thermodynamically favorable, generating enough energy and driving force for the densification of the final products under relatively low temperatures; in addition, chemical compatibility of the in situ formed phases and uniformity of phase distribution can also be achieved [40, 41]. Thermodynamic calculations demonstrate that most of the reactions during reactive sintering satisfy the conditions for self-sustaining combustion (Tadiabatic ≥ 1800 K and ΔHo298/Cp298 > 2000 K). Therefore, low heating rates (e.g., ~1°C/min) and extended holding times (e.g., 360 min) at selected temperatures (e.g., 600°C) will promote reaction between the starting materials without igniting self-sustaining combustion [40, 42]. In limited cases, however, combustion reactions are beneficial for densification and can promote unique microstructure in the final products [41, 43].

- Reactive sintering process can produce diboride-based ceramics with anisotropic microstructures. Phases formed in situ are highly reactive due to small size and large surface areas. In addition, transient liquid phases can be formed, which promote mass transport and anisotropic grain growth. The result can be anisotropic MeB2 grains in the final microstructure, either rodlike or platelet. Because MeB2 ceramics have primitive hexagonal crystal structures, growth of either rodlike or platelet grains is possible due to preferred growth along the c-axis (rods) or a and b-axes (platelets). For UHTCs, however, only a few reports have described this phenomenon. Anisotropic grain growth mechanisms are still under investigation. Even so, this phenomenon can provide for microstructure tailoring and property improvements for UHTCs [37, 43–46].

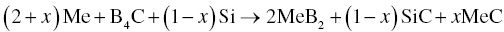

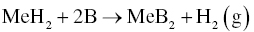

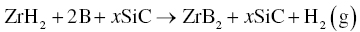

Elemental transition metals (Me) or transition metal hydrides (MeH2) are commonly used as the transition metal source (Fig. 3.1) to minimize the introduction of MeO2 contamination. The boron source is elemental B or some boron-containing compounds, such as B4C and BN. Moreover, because MeB2-based ceramics can contain other phases, such as SiC, ZrC, and MoSi2, boron-containing compounds are also C or N sources for the final products. Reduction processes that are used to synthesize MeB2 powders using MeO2 starting materials, as discussed in Section 3.2, are not viable approaches for reactive sintering. One reason is that most of the reduction processes are highly endothermic, and the Gibbs's free energy becomes negative at temperatures that would promote densification (e.g., >1500°C). Reduction reactions also lead to significant gas release, especially B2O3, which interferes with densification. In addition, the use of MeO2 starting powders typically results in the retention of unreacted MeO2 or other oxygen impurities in the final ceramic. As a result, most reactive sintering processes use elements or nonoxide compounds as starting materials to minimize introduction of oxygen impurities.

In this section, we discuss the fabrication of MeB2-based UHTC by reactive sintering. Because some MeB2 phases formed during the reactive process demonstrate anisotropic morphology, textured microstructures will be discussed.

3.4.1 Reactive Sintering from Transition Metals and Boron-Containing Compounds

3.4.1.1 MeB2–SiC Ceramics.

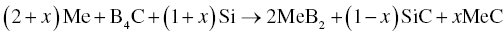

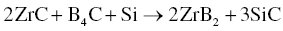

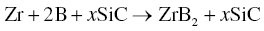

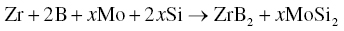

MeB2–SiC ceramics have an excellent combination of properties and have received the most attention among MeB2-based UHTCs. Zhang et al. [36] prepared ZrB2–SiC composites by RHP using Zr, Si, and B4C as starting powders under vacuum at 1900°C for 1 h, according to Reaction 3.23.

A mechanism for the RHP process was proposed as shown in Figure 3.9. During RHP, B and C atoms in B4C will diffuse into Zr and Si, respectively, and form ZrB2 and SiC in situ. Because the diffusion of Zr and Si atoms is slow, the as-synthesized ZrB2 and SiC possess features of the starting powders. The particle size of SiC was generally <3 µm, whereas that of ZrB2 was larger, in the range of 3–10 µm, compared with starting particle sizes of <10 µm for and <43 µm for Zr. The RHP process resulted in relatively small grain sizes for both ZrB2 and SiC, resulting in an improvement of the mechanical properties compared with ZrB2–SiC prepared by conventional HP. Subsequently, Zhao et al. also prepared ZrB2–SiC by R-SPS using the same starting materials [47, 48]. After SPS, a fine homogeneous microstructure was obtained with grain sizes of <5 µm for ZrB2 and <1 µm for SiC. In addition, Zimmermann et al. fabricated ZrB2–SiC ceramics by RHP using ZrH2, B4C, and Si as given in Reaction 3.24 [49].

Figure 3.9. Microstructure formation mechanism of the ZrB2–SiC composite in the reaction-synthesis process, depicting the transformation from (a) the powder compact to (b) the final microstructure of the composite [36].

3.4.1.2 MeB2–SiC–(Third Phase) Cramics.

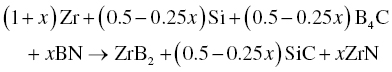

Similar to the production of MeB2–SiC composites, Zr, B4C, and Si were used as starting powders to prepare ZrB2–SiC–ZrC composites by RHP according to Reaction 3.25 [37].

When x = 0, Reaction 3.25 reduces to Reaction 3.23, which is a special case of Reaction 3.25. For Reaction 3.25, increasing the amount of Zr and reducing the amount of Si result in the formation of a third-phase ZrC, which is also a UHTC. Further investigation of Reaction 3.25 revealed that it may consist of two subreactions, Reactions 3.26 and 3.27.

This means that reactive process could produce ZrC at relatively low temperatures (~800°C), and as the temperature increases, ZrB2 could become the main phase. In addition, SiC appeared, and the amount of ZrC decreased at the same time according to Reaction 3.27. In view of these reaction steps, Wu optimized the model of the phase formation sequence during RHP of Zr, Si, and B4C (Fig. 3.10). The same RHP process can also be used to prepare HfB2–SiC ceramics using Hf, Si, and B4C as starting materials [50].

Figure 3.10. Microstructure formation mechanism of ZrB2–ZrC–SiC composites in the reaction-synthesis process, depicting conversion from (a) the powder compact to (b) the intermediate state, and (c) the final microstructure [37].

To highlight the differences between reactive and nonreactive processes, Zhang et al. fabricated ZrB2–SiC–ZrC composites in two ways: (1) from ZrB2, SiC, and ZrC by HP; and (2) from Zr, B4C, and Si by RHP [45, 46]. By HP, the ZrB2 grains were equiaxed, while the RHP composite had a mixture of equiaxed and platelike ZrB2 grains. The reactive process enabled the preparation of ZrB2-based ceramics with anisotropic grains.

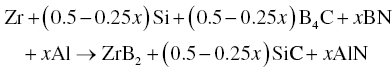

In addition to ZrB2–SiC and ZrB2–SiC–ZrC, Wu et al. prepared ZrB2–SiC–ZrN and ZrB2–SiC–AlN composites by adding BN and Al to Zr, Si, and B4C (Reactions 3.28 and 3.29) [51]. Similarly, ZrB2–SiC–BN [52, 53] and ZrB2–SiC–ZrN [54] composites were prepared using Zr, Si3N4, and B4C batched according to Reactions 3.30 and 3.31.

Wu prepared these composites by both RHP and R-SPS. The R-SPS process formed more homogeneous and finer microstructures because of its high heating rate and short holding time, while RHP process produced coarse microstructures due to a holding time that was long enough for grain growth to proceed. The short holding time and finer microstructure of the final products in the SPS process also improved the densification behavior of the materials.

3.4.1.3 Other MeB2-Based Ceramics.

Johnson et al. used the directed reaction of liquid metal with B4C to yield platelet-reinforced carbide matrix materials [55–57]. ZrB2–ZrCx–Zr were obtained by the process described by Reaction 3.32.

The composites were composed of ZrB2 platelets distributed uniformly in a matrix of equiaxed ZrCx grains, while the residual Zr metal was generally situated at the grain triple points (Fig. 3.11). These platelet-reinforced ceramics exhibited an attractive combination of high strength (800–1030 MPa), fracture toughness (11–23 MPa⋅m1/2), and thermal conductivity (50–70 W/m⋅K) over the temperature range of 25–600°C, which highlights the advantages of the ceramics prepared by reactive process. However, the Ultra-High temperature properties of these composites may be affected by the small amount of residual Zr metal that remained.

Figure 3.11. Backscattered electron images of the cross section of a typical ZrB2-platelet-reinforced ZrC product taken approximately 2 mm from the top (a) and bottom (b) of a 12.7-mm-thick part. The darkest phase is ZrB2, the gray phase is ZrC, and the lightest phase is zirconium metal [54].

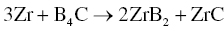

Zhang et al. prepared ZrB2–ZrC ceramics using Zr and B4C as starting materials, according to Reaction 3.33 [58].

Because the diffusion of carbon was much faster than boron in zirconium, only carbon reached the center of the large Zr particles, which resulted in a microstructure with large ZrC agglomerates surrounded by fine ZrB2 and ZrC particles.

Using Zr and BN as starting materials, Zhang also prepared ZrB2–ZrN (Reaction 3.34). Similarly, ZrB2–AlN could be prepared by adding Al to those precursors (Reaction 3.35) [58].

The final composites had homogeneous microstructures with fine grain sizes. For the Zr–BN system, the researchers determined that the diffusion coefficient of N was smaller than that of C, but close to that of B. Accordingly, homogeneous microstructures were obtained due to the mutual constraint of grain growth for the two phases that formed, which restrained abnormal grain growth in both ZrB2 and ZrN. In the Zr–Al–BN system, Al melted at temperatures as low as 660°C and the maximum solubilities of Al were 11.5 at% α-Zr and 26 at% in β-Zr. Accordingly, the redistribution of Zr and Al was remarkable in this system, producing fine, homogeneous microstructures.

3.4.2 Reactive Sintering from Transition Metals and Boron

3.4.2.1 Monolithic MeB2 Ceramics.

Elemental Me or MeH2 together with B can be used to prepare monolithic MeB2 ceramics by Reactions 3.1 or 3.36.

Chamberlain et al. [42, 59] prepared monolithic ZrB2 ceramics by RHP of Zr and B and studied the reaction mechanism. Analysis concluded that B diffused into the Zr granules to form ZrB2. This behavior was observed in diffusion couple experiments in which polished Zr was heated to 1450°C in contact with B. Given this reaction path, the size and shape of the Zr precursor determined the size and shape of the resulting ZrB2. Attrition milling of the precursors produced nanosized (<100 nm) Zr metal particles, which reacted with B at temperatures as low as 600°C. This process produced ZrB2 with an average particle size of less than 100 nm. The nano-crystalline ZrB2 exhibited significant coarsening and densification between 600 and 1450°C, which was the result of fine particle size and, possibly, a high defect concentration. Significant particle coarsening below 1650°C decreased the sinterability of ZrB2. As a result, a temperature of 2100°C was required to achieve full density. Consolidation of ZrB2 at 2100°C resulted in large grains (~12 µm), leading to lower strength.

3.4.2.2 MeB2–SiC Ceramics.

The addition of other phases to Me and B can enable the production of MeB2-based ceramics. Chamberlain et al. used Zr, B, and SiC along with small amounts of B4C (0.5 wt%, to react with oxygen impurities) to prepare ZrB2–SiC ceramics by RHP [40]. Samples with relative densities in excess of 95% were produced at 1650°C based on Reaction 3.37.

In this case, SiC functions not only as an important second phase that improves the microstructure and properties of the resulting ceramics, but also as an inert diluent that reduces the potential for a self-propagating reaction to ignite.

Using ZrH2 as the transition metal source, together with B, SiC, and B4C, Ran prepared fully densified ZrB2–20 vol%SiC composites by reactive pulsed electric current sintering (R-PECS) by the process described in Reaction 3.38 [43].

The study revealed that ZrH2 first decomposed into metal Zr before reacting with B to form ZrB2. Since metal Zr is ductile and difficult to mill down to small particle sizes, the use of brittle ZrH2 was thought to be a suitable alternative, which made it easier to obtain small starting particles. The same concept is also used to prepare TiB2-based ceramics using TiH2 as a precursor [60–63].

Besides enhanced densification, Ran's experiments revealed another interesting phenomenon, which was orientation of ZrB2 grains. The XRD patterns indicated that the (001) peaks had higher intensity than the (100) peaks in ZrB2–SiC ceramics, which was different from the reference pattern of Figure 3.12. This implied that the hexagonal ZrB2 grains had grown in a preferred direction and the mechanism of orientation of ZrB2 grains was attributed to an anisotropic Ostwald ripening process under pressure [43].

Figure 3.12. ZrB2 JCPDS 35-0741 reference (a) and XRD patterns of cross section (b) and sintered surface (c) surface of the PECS samples [43].

3.4.2.3 MeB2–MoSi2 Ceramics.

ZrB2–MoSi2 ceramics are another important member of the ZrB2-based UHTC family. Using elemental Zr, B, Mo, and Si as starting materials, Wu et al. prepared ZrB2–MoSi2 ceramics via RHP, according to reaction 3.39 [44]:

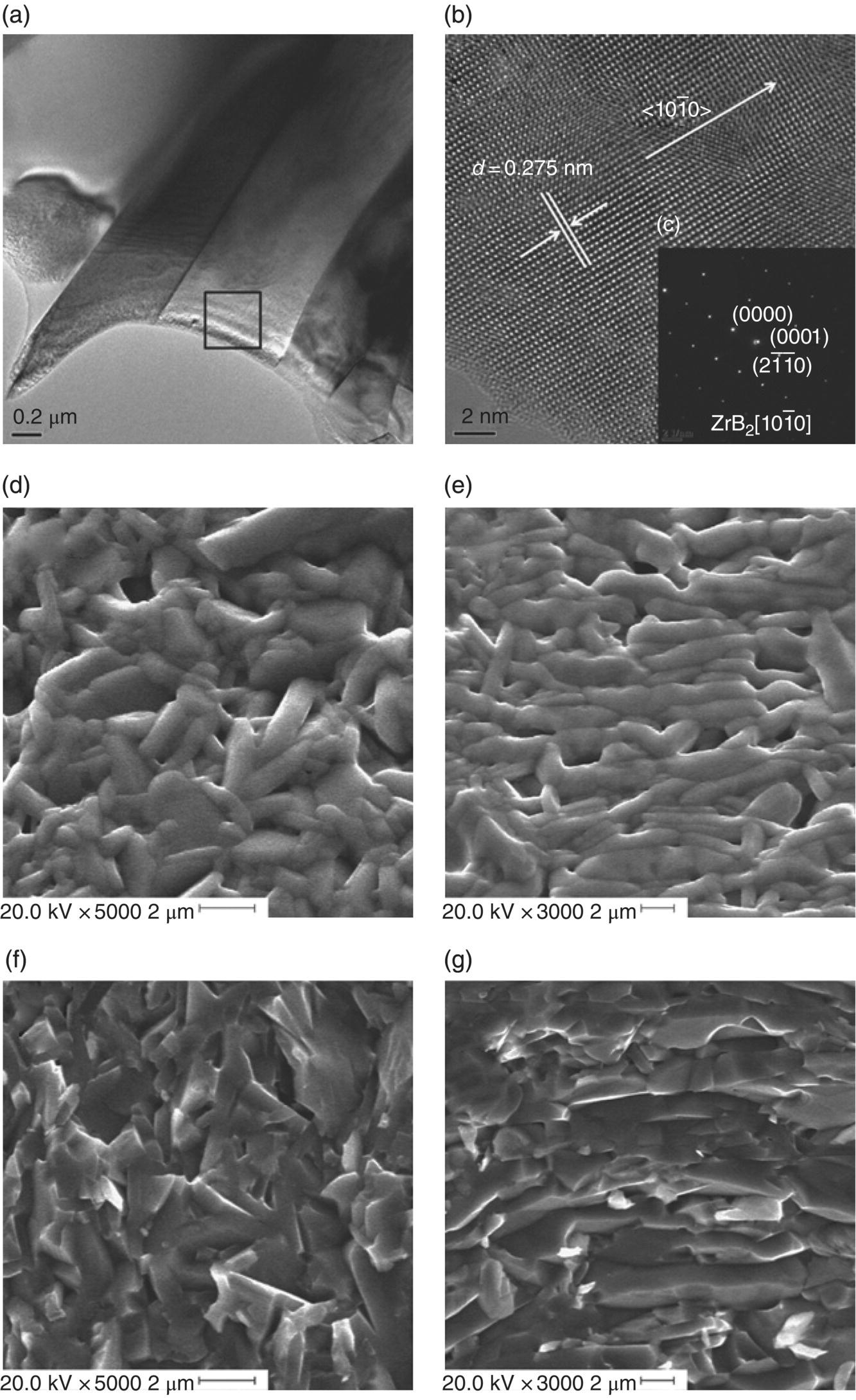

Due to the ductility of MoSi2 at temperatures over 1000°C, the MoSi2 grains deformed to fill the voids in the ZrB2 skeleton, thus favoring the formation of a porosity-free material. The ZrB2 grains had a platelet morphology, which was found only during the RHP process, not for materials prepared by PLS, HP, or SPS. The anisotropic grain growth was attributed to the in situ formation of ZrB2 grains with high chemical activity. The difference in surface energy on different planes favored the elongation of ZrB2 grains through Ostwald ripening at higher temperatures [64].

Liu et al. used RHP and subsequent hot forging to tailor the microstructure of ZrB2–MoSi2 ceramics [65]. The result was a textured and platelet-reinforced ZrB2-based UHTC. During hot forging, the platelet ZrB2 grains grew and simultaneously, under the applied pressure, rotated and rearranged to align along the top surface of the specimen (Fig. 3.13). The textured composites showed a remarkable improvement in mechanical properties, with flexural strengths as high as 871 MPa after hot forging, compared to 572 MPa before hot forging [65, 66].

Figure 3.13. (a and b) TEM image of ZrB2 platelet grains at different magnifications; (c) selected-area electron diffraction pattern of platelet grains of (b); (d and e) SEM images of polished surfaces before and after hot forging; (f and g) SEM images of fractured surface before and after hot forging [62].

In summary, during the MeB2 life cycle, reactive sintering process can realize the fabrication of MeB2-based ceramics from Me and B in one step, which simplifies the procedure compared with the two-step processes that separate synthesis and sintering densification. Relatively low densification temperatures are another advantage of reactive sintering, which are due to chemical reactions during the process and the heat generated from them. The RHP process also provides the opportunity for reduced contamination from oxygen impurities due to the removal of an oxide source to generate the MeB2 powders. Another incomparable strong point is that reactive sintering processes provide a chance for anisotropic growth of MeB2 grains, which is beneficial for the microstructure tailoring and property improvement. Finally, optimized microstructure and enhanced performance play important roles and increase the life of UHTCs during the application process, which is the other part of the MeB2 life cycle.

3.5 Summary

This chapter discussed reactive processes for the synthesis and densification of boride-based UHTCs as part of an overall life cycle. The properties and performances of UHTCs are dependent on the powder properties, densification processes, and microstructures, so optimization of reactive processes is important for the use of UHTCs in the high-temperature structures and other extreme environments. The discussions given earlier provide information about fabrication processes, phase formation mechanisms, microstructure evolution, and property improvements for UHTCs.

References

- 1. Karasev AI. Preparation of technical zirconium diboride by the carbothermic reduction of mixtures of zirconium and boron oxides. Powder Metall Met Ceram 1973;12 (11):926–929.

- 2. Funke VF, Yudkovskii SI. Preparation of zirconium boride. Powder Metall Met Ceram 1964;2 (4):293–296.

- 3. Kuzenkova MA, Kislyi PS. Preparation of zirconium diboride. Powder Metall Met Ceram 1965;4 (12):966–969.

- 4. Zhao H, He Y, Jin ZZ. Preparation of zirconium boride powder. J Am Ceram Soc 1995;78 (9):2534–2536.

- 5. Guo WM, Zhang GJ. Reaction processes and characterization of ZrB2 powder prepared by boro/carbothermal reduction of ZrO2 in vacuum. J Am Ceram Soc 2009;92 (1):264–267.

- 6. Ni DW, Zhang GJ, Kan YM, Wang PL. Synthesis of monodispersed fine hafnium diboride powders using carbo/borothermal reduction of hafnium dioxide. J Am Ceram Soc 2008;91 (8):2709–2712.

- 7. Peshev P, Bliznakov G. On the borothermic preparation of titanium, zirconium and hafnium diborides. J Less Common Metals 1968;14 (1):23–32.

- 8. Ran SL, Van der Biest O, Vleugels J. ZrB2 powders synthesis by borothermal reduction. J Am Ceram Soc 2010;93 (6):1586–1590.

- 9. Ni DW, Zhang GJ, Kan YM, Wang PL. Hot pressed HfB2 and HfB2-20 vol%SiC ceramics based on HfB2 powder synthesized by borothermal reduction of HfO2. Int J Appl Ceram Technol 2010;7 (6):830–836.

- 10. Guo WM, Zhang GJ. New borothermal reduction route to synthesize submicrometric ZrB2 powders with low oxygen content. J Am Ceram Soc 2011;94 (11):3702–3705.

- 11. Zou J, Zhang GJ, Vleugels J, Van der Biest O. High temperature strength of hot pressed ZrB2–20vol% SiC ceramics based on ZrB2 starting powders prepared by different carbo/boro-thermal reduction routes. J Eur Ceram Soc 2013;33 (10):1609–1614.

- 12. Wu WW, Zhang GJ, Kan YM, Wang PL. Combustion synthesis of ZrB2-SiC composite powders ignited in air. Mater Lett 2009;63 (16):1422–1424.

- 13. Zou J, Zhang GJ, Hu CF, Nishimura T, Sakka Y, Tanaka H, Vleugels J, Van der Biest O. High-temperature bending strength, internal friction and stiffness of ZrB2-20 vol% SiC ceramics. J Eur Ceram Soc 2012;32 (10):2519–2527.

- 14. Baik S, Becher PF. Effect of oxygen contamination on densification of TiB2. J Am Ceram Soc 1987;70 (8):527–530.

- 15. Zhang SC, Hilmas GE, Fahrenholtz WG. Pressureless densification of zirconium diboride with boron carbide additions. J Am Ceram Soc 2006;89 (5):1544–1550.

- 16. Wang XG, Guo WM, Zhang GJ. Pressureless sintering mechanism and microstructure of ZrB2-SiC ceramics doped with boron. Scripta Mater 2009;61 (2):177–180.

- 17. Guo WM, Zhang GJ, Yang ZG. Pressureless sintering of zirconium diboride ceramics with boron additive. J Am Ceram Soc 2012;95 (8):2470–2473.

- 18. Monteverde F. Hot pressing of hafnium diboride aided by different sinter additives. J Mater Sci 2008;43 (3):1002–1007.

- 19. Zhang H, Yan YJ, Huang ZR, Liu XJ, Jiang DL. Pressureless sintering of ZrB2-SiC ceramics: the effect of B4C content. Scripta Mater 2009;60 (7):559–562.

- 20. Zou J, Zhang GJ, Kan YM, Ohji T. Pressureless sintering mechanisms and mechanical properties of hafnium diboride ceramics with pre-sintering heat treatment. Scripta Mater 2010;62 (3):159–162.

- 21. Zou J, Zhang GJ, Kan YM. Pressureless densification and mechanical properties of hafnium diboride doped with B4C: from solid state sintering to liquid phase sintering. J Eur Ceram Soc 2010;30 (12):2699–2705.

- 22. Zhu SM, Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE, Zhang SC. Pressureless sintering of carbon-coated zirconium diboride powders. Mater Sci Eng A 2007;459 (1–2):167–171.

- 23. Guo WM, Yang ZG, Zhang GJ. Effect of carbon impurities on hot-pressed ZrB2-SiC ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc 2011;94 (10):3241–3244.

- 24. Zhu S, Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE, Zhang SC. Pressureless sintering of zirconium diboride using boron carbide and carbon additions. J Am Ceram Soc 2007;90:3660–3663.

- 25. Zhang SC, Hilmas GE, Fahrenholtz WG. Pressureless sintering of ZrB2-SiC ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc 2008;91 (1):26–32.

- 26. Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE, Zhang SC, Zhu S. Pressureless sintering of zirconium diboride: particle size and additive effects. J Am Ceram Soc 2008;91 (5):1398–404.

- 27. Chamberlain AL, Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE. Pressureless sintering of zirconium diboride. J Am Ceram Soc 2006;89 (2):450–456.

- 28. Zou J, Zhang GJ, Sun SK, Liu HT, Kan YM, Liu JX, Xu CM. ZrO2 removing reactions of Groups IV-VI transition metal carbides in ZrB2 based composites. J Eur Ceram Soc 2011;31 (3):421–427.

- 29. Zou J, Zhang GJ, Kan YM. Formation of tough interlocking microstructure in ZrB2-SiC-based ultrahigh-temperature ceramics by pressureless sintering. J Mater Res 2009;24 (7):2428–2434.

- 30. Zou J, Sun SK, Zhang GJ, Kan YM, Wang PL, Ohji T. Chemical reactions, anisotropic grain growth and sintering mechanisms of self-reinforced ZrB2–SiC doped with WC. J Am Ceram Soc 2011;94 (5):1575–1583.

- 31. Ni DW, Liu JX, Zhang GJ. Pressureless sintering of HfB2-SiC ceramics doped with WC. J Eur Ceram Soc 2012;32 (13):3627–3635.

- 32. Chamberlain AL, Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE, Ellerby DT. High-strength zirconium diboride-based ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc 2004;87 (6):1170–1172.

- 33. Zou J, Zhang GJ, Kan YM, Wang PL. Pressureless densification of ZrB2-SiC composites with vanadium carbide. Scripta Mater 2008;59 (3):309–312.

- 34. Zou J, Zhang GJ, Kan YM, Wang PL. Hot-pressed ZrB2-SiC ceramics with VC addition: chemical reactions, microstructures, and mechanical properties. J Am Ceram Soc 2009;92 (12):2838–2846.

- 35. Zou J, Zhang GJ, Hu CF, Nishimura T, Sakka Y, Vleugels J, Biest O. Strong ZrB2-SiC-WC ceramics at 1600 degrees C. J Am Ceram Soc 2012;95 (3):874–878.

- 36. Zhang GJ, Deng ZY, Kondo N, Yang JF, Ohji T. Reactive hot pressing of ZrB2-SiC composites. J Am Ceram Soc 2000;83 (9):2330–2332.

- 37. Wu WW, Zhang GJ, Kan YM, Wang PL. Reactive hot pressing of ZrB2-SiC-ZrC ultra high-temperature ceramics at 1800 degrees C. J Am Ceram Soc 2006;89 (9):2967–2969.

- 38. Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE, Talmy IG, Zaykoski JA. Refractory diborides of zirconium and hafnium. J Am Ceram Soc 2007;90 (5):1347–1364.

- 39. Zhang GJ, Zou J, Ni DW, Liu HT, Kan YM. Boride ceramics: densification, microstructure tailoring and properties improvement. J Inorg Mater 2012;27 (3):225–233.

- 40. Chamberlain AL, Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE. Low-temperature densification of zirconium diboride ceramics by reactive hot pressing. J Am Ceram Soc 2006;89:3638–3645.

- 41. Wu WW, Zhang GJ, Kan YM, Wang PL. Reactive hot pressing of ZrB2-SiC-ZrC composites at 1600 degrees C. J Am Ceram Soc 2008;91 (8):2501–2508.

- 42. Chamberlain AL, Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE. Reactive hot pressing of zirconium diboride. J Eur Ceram Soc 2009;29 (16):3401–3408.

- 43. Ran S, Van der Biest O, Vleugels J. ZrB2-SiC composites prepared by reactive pulsed electric current sintering. J Eur Ceram Soc 2010;30 (12):2633–2642.

- 44. Wu WW, Wang Z, Zhang GJ, Kan YM, Wang PL. ZrB2-MoSi2 composites toughened by elongated ZrB2 grains via reactive hot pressing. Scripta Mater 2009;61 (3):316–319.

- 45. Qu Q, Zhang XH, Meng SH, Han WB, Hong CQ, Han HC. Reactive hot pressing and sintering characterization of ZrB2-SiC-ZrC composites. Mater Sci Eng A 2008;491 (1–2):117–123.

- 46. Zhang XH, Qu Q, Han JC, Han WB, Hong CQ. Microstructural features and mechanical properties of ZrB2-SiC-ZrC composites fabricated by hot pressing and reactive hot pressing. Scripta Mater 2008;59 (7):753–756.

- 47. Zhao Y, Wang LJ, Zhang GJ, Jiang W, Chen LD. Preparation and microstructure of a ZrB2-SiC composite fabricated by the spark plasma sintering-reactive synthesis (SPS-RS) method. J Am Ceram Soc 2007;90 (12):4040–4042.

- 48. Zhao Y, Wang LJ, Zhang GJ, Jiang W, Chen LD. Effect of holding time and pressure on properties of ZrB2-SiC composite fabricated by the spark plasma sintering reactive synthesis method. Int J Refract Method Hard Mater 2009;27 (1):177–180.

- 49. Zimmermann JW, Hilmas GE, Fahrenholtz WG, Monteverde F, Bellosi A. Fabrication and properties of reactively hot pressed ZrB2-SiC ceramics. J Eur Ceram Soc 2007;27 (7):2729–2736.

- 50. Monteverde F. Progress in the fabrication of ultra-high-temperature ceramics: “in situ” synthesis, microstructure and properties of a reactive hot-pressed HfB2-SiC composite. Compos Sci Technol 2005;65 (11–12):1869–1879.

- 51. Wu WW, Zhang GJ, Kan YM, Wang PL, Vanmeensel K, Vleugels J, Van der Biest O. Synthesis and microstructural features of ZrB2-SiC-based composites by reactive spark plasma sintering and reactive hot pressing. Scripta Mater 2007;57 (4):317–320.

- 52. Wu WW, Xiao WL, Estili M, Zhang GJ, Sakka Y. Microstructure and mechanical properties of ZrB2-SiC-BN composites fabricated by reactive hot pressing and reactive spark plasma sintering. Scripta Mater 2013;68 (11):889–892.

- 53. Wu WW, Estili M, Nishimura T, Zhang GJ, Sakka Y. Machinable ZrB2–SiC–BN composites fabricated by reactive spark plasma sintering. Mater Sci Eng A 2013;582:41–46.

- 54. Wu WW, Zhang GJ, Kan YM, Sakka Y. Synthesis, microstructure and mechanical properties of reactively sintered ZrB2-SiC-ZrN composites. Ceram Int 2013;39 (6):7273–7277.

- 55. Johnson WB, Claar TD, Schiroky GH. Preparation and processing of platelet-reinforced ceramics by the directed reaction of zirconium with boron carbide. Ceram Eng Sci Proc 1989;10 (7-8):588–598.

- 56. Claar TD, Johnson WB, Andersson CA, Schiroky GH. Microsturcture and properties of platelet-reinforced ceramics formed by the directed reaction of zirconium with boron carbide. Ceram Eng Sci Proc 1989;10 (7–8):599–609.

- 57. Johnson WB, Nagelberg AS, Breval E. Kinetics of formation of a platelet-reinforced ceramic composite prepared by the directed reaction of zirconium with boron-carbide. J Am Ceram Soc 1991;74 (9):2093–2101.

- 58. Zhang GJ, Ando M, Yang JF, Ohji T, Kanzaki S. Boron carbide and nitride as reactants for in situ synthesis of boride-containing ceramic composites. J Eur Ceram Soc 2004;24 (2):171–178.

- 59. Fahrenholtz WG. Reactive processing in ceramic-based systems. Int J Appl Ceram Technol 2006;3 (1):1–12.

- 60. Zhang GJ, Jin ZZ, Yue XM. TiB2-Ti(C,N)-SiC composites prepared by reactive hot pressing. J Mater Sci Lett 1996;15 (1):26–28.

- 61. Zhang GJ, Jin ZZ, Yur XM. A multilevel ceramic composite of TiB2-Ti0.9W0.1C-SiC prepared by in situ reactive hot pressing. Mater Lett 1996;28 (1–3):1–5.

- 62. Zhang GJ, Yue XM, Jin ZZ. Preparation and microstructure of TiB2-TiC-SiC platelet-reinforced ceramics by reactive hot-pressing. J Eur Ceram Soc 1996;16 (10):1145–1148.

- 63. Zhang GJ, Yue XM, Jin ZZ, Dai JY. In-situ synthesized TiB2 toughened SiC. J Eur Ceram Soc 1996;16 (4):409–412.

- 64. Liu HT, Wu WW, Zou J, Ni DW, Kan YM, Zhang GJ. In situ synthesis of ZrB2-MoSi2 platelet composites: reactive hot pressing process, microstructure and mechanical properties. Ceram Int 2012;38 (6):4751–4760.

- 65. Liu HT, Zou J, Ni DW, Wu WW, Kan YM, Zhang GJ. Textured and platelet-reinforced ZrB2-based ultra-high-temperature ceramics. Scripta Mater 2011;65 (1):37–40.

- 66. Liu HT, Zou J, Ni DW, Liu JX, Zhang GJ. Anisotropy oxidation of textured ZrB2-MoSi2 ceramics. J Eur Ceram Soc 2012;32 (12):3469–3476.