5

Near-Net-Shaping of Ultra-High Temperature Ceramics

Carolina Tallon1,2 adn George V. Franks1,2

1 Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, The University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

2 Defence Materials Technology Centre (DMTC), Hawthorn, Australia

5.1 Introduction

Ultra-High temperature ceramics (UHTCs) are difficult to densify for the same reason they have high melting temperatures, namely, strong bonding between atoms. As such, diffusion is typically low, and pressureless sintering (PS) of dry pressed components does not lead to ceramics with high relative density. Therefore, UHTCs are usually densified by hot pressing (HP), hot isostatic pressing (HIPing), or spark plasma sintering (SPS) [1–5]. These techniques are more expensive than PS due to the application of pressure and/or the use of consumable dies in processing. Furthermore, only simple shapes (generally limited to axially symmetric shapes of uniform cross section like cylinders or tiles) can be produced by HP and SPS. Such shapes are of limited use in most applications where complex-shaped components are required. To produce components with complex shapes, HPed or HIPed billets need extensive diamond grinding. To avoid diamond grinding, shaping components in the green stage followed by PS is preferred [6–9].

Green bodies with uniform and high particle packing density are more amenable to densification by PS than green bodies with low particle packing density [10]. High and uniform particle packing can be obtained by consolidation of particles that interact with repulsive forces [11]. Conventional dry pressing techniques are not effective because dry systems have no mechanism to develop repulsion between particles (only van der Waals attraction is active). In contrast, wet (colloidal) processing can be effective in producing consolidated green bodies with uniform and high green density [9, 10]. Suspending ceramic particles in a liquid is a possible way to control solution chemistry and produce repulsion among particles as discussed in the next section. Well-dispersed suspensions (particles interacting via repulsion) enable a number of consolidation techniques, which produce high and uniform particle packing. These techniques are described in the third section of this chapter. Colloidal forming techniques have three desirable characteristics. First, they allow for enhanced densification without pressure and, potentially, at lower sintering temperatures. Second, they can be used to produce complex-shaped objects that need little, if any, diamond machining. Finally, they enable deagglomeration and allow for removal of flaws, which enhances reliability [9, 10].

The main driving force for sintering is the reduction in surface energy because high-energy particle surfaces are replaced by internal interfaces (such as grain boundaries) as densification proceeds. As such, fine particles (micrometer or smaller) with high surface area are more amenable to sintering than coarse particles (tens to hundreds of µm in diameter). Therefore, the use of fine particles is preferred and can produce high-density sintered components by PS.

5.2 Understanding Colloidal Systems: Interparticle Forces

Fine particles used in colloidal powder processing have a high surface area-to-volume ratio. The behavior of fine particles is dominated by surface forces rather than volume forces (due to mass) and are called colloids. The relative influence can be understood by considering the consequences of being hit in the head with a baseball compared to having a cup of flour (same mass as the baseball) thrown on your head. The baseball has large mass so you feel the impact, but the surface adhesive forces are small so that ball drops to the ground via gravity after the impact. The particles of flour have small mass individually, so they cause little pain when they impact your head, but because the surface adhesive forces are greater than the force of gravity, the flour sticks to your hair and skin.

The mass of colloidal particles is small enough that energy from thermally induced vibrations of liquid molecules is transferred to the solid particles, which causes them to move within the liquid. This phenomenon is known as Brownian motion. In the absence of other forces, Brownian motion will maintain particles in a constantly moving randomized structure [12]. On Earth, particles also experience the force of gravity (a body force). Eventually, gravity wins, and particles settle out of suspension. However, Brownian motion can dominate for extended periods of time, which may be much longer than the processing time. Small particles, such as fine ceramics, will usually be stable against sedimentation for periods of an hour or so and up to a few days, if gently stirred or rolled.

For fine ceramic particles, surface forces dominate the behavior in suspension rather than Brownian or gravity forces. The surface forces may be either attractive or repulsive. Depending on the total of the attraction and repulsion of all the surfaces forces operating in a particular situation, either net attraction or net repulsion can result (Fig. 5.1). In the case of net repulsion, the particles remain dispersed in the suspension as individual particles and then Brownian motion usually dominates over gravity for sufficient time to produce a suspension that is stable against sedimentation. If net attraction is the result, the particles will aggregate into larger, more massive aggregates or flocs. In these suspensions, gravity dominates, and the large heavy aggregates tend to settle out of suspension. The surface forces also control behavior including suspension rheology and particle packing as illustrated in Table 5.1.

Figure 5.1. Representation of the repulsion and attraction forces as a function of interparticle distance. (a) When ceramic particles are suspended in a polar solvent, particle surfaces become charged depending on the chemistry and pH of the solution. M–OH groups represent surface hydroxyl group that reacts with acid or base. (b) The surface charge is balanced with a counterion cloud around the particle to provide electrical neutrality. Surface charge and the counterion cloud form the electrical double layer. (c) In addition to using the EDL to create repulsive forces between particles, steric and electrosteric mechanisms could be used by adding polymers or polyelectrolytes, respectively, which will adsorb on particle surfaces.

Table 5.1 Influence of surface forces on suspension behavioraa

| Repulsion | Attraction | |

| Typical behavior | Individual dispersed particles Slow settling Low viscosity High and uniform particle packing |

Aggregation Rapid sedimentation High viscosity and yield stress Low and pressure-sensitive particle packing |

| Typical causes | EDL repulsion (high zeta potential) Low salt concentration Steric repulsion |

Van der Waals attraction Low zeta potential High salt concentration Bridging polymer flocculation |

a Refs. 12 and 13.

The most technologically significant interparticle surface forces are van der Waals, electrical double layer (EDL), steric repulsion, and bridging flocculation.

The van der Waals interaction between particles is due to the sum of individual dipole moment interactions among all of the atoms in the two particles. Every atom in each particle acts as a fluctuating dipole. At every instant, a dipole is created by the separation of the nucleus of an atom (positive) and its electron cloud (negative). That dipole moment fluctuates around the atom at a very fast rate. The electric field emanating from the instantaneous fluctuating dipole moment of one atom influences the dipole moments of the other atoms in both particles. All of the atoms in both particles correlate their dipole moments resulting in the minimum energy configuration. In the case of two particles of the same material interacting across a third medium, the resulting net interaction created by the sum of all of the dipole–dipole interactions is a net attraction [12, 14]. The magnitude of the interaction depends upon the index of refraction and dielectric properties of the particles and intervening medium. Generally speaking, higher-density materials have stronger van der Waals attraction. The magnitude of the interaction can be characterized by a parameter called the Hamaker constant (A). If particles are dispersed in a fluid and no mechanism is present to create repulsion, the particles will be attracted to each other and aggregate. The van der Waals attractive force (FvdW) between two spherical particles can be estimated using the following equation [1]:

where r is the particle radius, and D is the surface-to-surface separation between the particles. The negative sign indicates attraction between the particles.

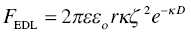

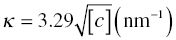

When particles are suspended in aqueous solutions, they can become charged due to reaction of the surface with either hydroxide (OH−) or hydronium (H3O+) ions in solution at high and low pH, respectively (Fig. 5.1a). Surface ionization occurs with the metal hydroxyl groups on metal oxide ceramics. In the case of UHTCs, a thin layer of oxide is found on the particle surfaces, so their charging behavior in solution is expected to be similar. However, their hydrophobic nature affects suspension preparation in aqueous solutions, as observed by Leo et al. [17]. For the sake of discussion; it is assumed that UHTCs have at least a surface monolayer of oxide. At low pH, the surface becomes positively charged, and at high pH, the surface is negative. Each type of surface has a particular reactivity with acid and base such that the pH where the surface is neutral depends upon the surface chemistry of the material. The pH where the material is neutral is known as the isoelectric point (IEP) and is shown in Table 5.2 for a range of UHTCs. Since the overall system is electrically neutral, the surface charge on the particles is balanced by oppositely charged counterions in the solution (Fig. 5.1b). The counterions form a cloud around the particles according to the Poisson–Boltzman distribution. The surface charge and cloud of counterions are known as the Electric Double Layer (EDL) [12, 14]. When two particles with the same charge approach one another, their counterion clouds overlap. The overlapping of these ion clouds results in increased ion concentration in the gap between the two particles. The increased ion concentration produces an osmotic pressure that pushes the particles apart. This repulsive force increases as particles come closer together and is known as EDL repulsion. The magnitude of the repulsive force is related to the zeta potential (ζ) of the particle surface, which is related to the surface charge (Fig. 5.1b). The zeta potential is zero at the IEP and increases in magnitude as the pH of the suspension moves away from the IEP. The EDL force (FEDL) drops off exponentially with distance between particles and can be estimated by Equation (5.2) for spherical particles (with the same zeta potential) under many conditions:

where ε is the dielectric constant of the solution, εo is the permittivity of free space, r is the radius of the particle, D is the surface-to-surface distance between the particles, and ĸ is the Debye screening parameter. The Debye screening parameter depends on the ionic strength (salt concentration) of the solution such that

where c is the molar concentration of monovalent electrolyte (salt) in the solution. If a suspension contains two different types of particles with different IEPs such that one particle has negative charge and another positive charge, the EDL force will be attractive. More detail about these type of interactions is available in the colloid and surface chemistry texts [12, 14].

The van der Waals force and the EDL force are the two forces that usually dominate behavior in aqueous suspensions. Together, these forces are known as the DLVO forces (after Derjaguin, Landau, Verwey, and Overbeek). In aqueous solutions, well-dispersed suspensions can be produced by adjusting the pH of the suspension to a few pH units away from the IEP so that sufficient magnitude of zeta potential (charge) is developed that the EDL repulsion dominates over van der Waal attraction. In nonaqueous suspensions, van der Waals forces are significant, but EDL forces are not usually important because the low dielectric constant of nonpolar solvents dramatically reduces the magnitude of the EDL forces.

Table 5.2 Isoelectric point (IEP) of most commonly used UHTCs and other relevant powders

| Powder | IEP | Supplier | Reference | |

| Borides | ZrB2 | 4 | H.C. Starck, Grade B, 2.3 µm, new batch powder received July 2013 | a |

| 4.7 | H.C. Starck | [15] | ||

| 5 | H.C. Starck, Grade B, 2.3 µm | [16] | ||

| 5 | H.C. Starck, Grade B, 2.3 µm | [17] | ||

| 5.8 | Grade ZrB2-F, Japan New Metals Co.; 2.12 µm | [18] | ||

| HfB2 | 2.4 | H.C. Starck, 11.5 µm | a | |

| 6.4 | Alfa Aesar, 2.9 µm | [19] | ||

| TiB2 | 4.5 | H.C. Starck, Grade F, 2.9 µm | a | |

| Carbides | TiC | 3.3 | Supplier: Zhuzhou Hard Alloy Plant, Hunan, China) 0.60 µm | [20] |

| 3.9 | Hefei Kaier Nanotechnology Development Co., Ltd., China; 40 nm | [21] | ||

| 4 | H.C. Starck, HV120, 3 µm | a | ||

| 4.3 | Supplier: H.C. Starck, 1.4 µm | [22] | ||

| 4.3 | Synthesized: Whiskers, 30 nm | [22] | ||

| 5 | H.C. Starck | [15] | ||

| ZrC | 3.8 | H.C. Starck, Grade B, 2.9 µm | a | |

| HfC | 2.7 | Micron Metals (Atlantic Equipment Engineers), HF301, -325mesh | a | |

| B4C | 5.5 | HC Starck; Grade HD15; 2.6 µm | [17] | |

| 6.8 | HC Starck; Grade HD15; 2.6 µm | a | ||

| SiC | 3 | Aldrich | [15] | |

| 3.5 | H.C. Starck, 2.1 µm | a | ||

| 4 | HSC from Superior Graphite | [15] | ||

| 4.8, 4.2, 3.3 | Grindwell Norton, Bangalore, India | [15] | ||

| Nitrides | TiN | 2.2 | T20412-20H, Sanhe Yanjiao Xinyu High Technology Company for Ceramic Materials, Beijing), 2.3 µm | [23] |

| 3.7 | Synthesized powder, 15-30 nm | [24] | ||

| 3.9 | H.C. Starck, Grade C, 2.8um | a | ||

| 4 | H.C. Starck, 1.2 µm | [25] | ||

| 4.3 | Supplier: H.C. Starck, 1.05 µm | [22] | ||

| Silicides | MoSi2 | 4.3 | Chida Materials Co., Ltd., China 2.5 µm | [19] |

a Measured by C. Tallon for this book chapter; 100 mg/l powder suspensions were prepared in KCl 10−2 M; pH was adjusted with HNO3 1 M and NaOH 1 M solutions using a Horiba pH meter. Suspensions were sonicated (Ultrasonic Horn, Misonix 4000, Farmingdale, NY) for 2 min and homogenized overnight to allow for surface equilibrium. The zeta potential measurements were carried out using Zetasizer NanoZS (Malvern, Sydney, Australia). The pH was measured just before loading the suspension in the measuring cell.

When soluble polymers are added to suspensions, the polymers can adsorb onto particle surfaces, which develops other forces (Fig. 5.1c). These forces, known as steric repulsion and bridging flocculation (attraction), can be important in both aqueous and nonaqueous ceramic particle suspensions. When the polymer has a relatively low molecular weight (10,000–500,000 Da) and added in concentration to completely cover the particle surface, the polymer chains form a cushion that prevents other particles from approaching, producing steric repulsion between particles [9, 26]. This mechanism is useful in developing well-dispersed suspensions in nonaqueous solvent, since the steric repulsion can overwhelm the van der Waals attraction in these systems, if the polymer type and dose are carefully selected. Steric repulsion can also be important in aqueous systems, but polyelectrolytes (charged polymers) can be used in aqueous systems so that both EDL and steric repulsion combine to aid in dispersing ceramic particles. If the polymer is only poorly soluble in the solvent, steric attraction can develop between particles. This condition is usually to be avoided in ceramic powder processing where well-dispersed suspensions are desirable. If the soluble polymer has a high molecular weight (greater than about a million dalton) and is added in concentrations such that it covers only about half of the surface of the particles, the polymer can bridge between two or more particles resulting in attraction between particles known as bridging flocculation [27]. Again, this condition is usually avoided in ceramic powder processing. Additionally, a special type of attraction could also occur between particles in water, if they are not wetted by water. This force, known as hydrophobic attraction, causes aggregation between particles that have high contact angle with water and can be a reason why some particles are not easily dispersed in water.

As illustrated in Table 5.1, the net particle interaction force has a dramatic effect on suspension behavior. Two aspects of suspension behavior, in particular, are important in near-net-shaping of UHTC components. The first aspect is suspension viscosity, which needs to be maintained as low as possible with a volume fraction of solids that is as high as possible. For most colloidal processing methods, viscosity must be kept low (except, e.g., in 3D printing of pastes), so that suspension can be poured or injected into a complex shaped die cavity for the near-net-shaping processes described in the next section. The volume fraction must be high to produce a high-density green body and enable PS. The second aspect is the particle packing during consolidation, which should be as high as possible and uniform. High-density green bodies enable PS at as low a temperature as possible, and uniformity of particle packing ensures uniform shrinkage to avoid distortion and stresses during sintering.

Suspension rheology (flow behavior) is related to several factors including particle volume fraction, particle size, and interparticle forces [12, 13, 28, 29]. Suspension viscosity increases dramatically as volume fraction increases and asymptotes to very high value as a maximum particle fraction (usually around 64 vol%) is approached. The viscosity of concentrated suspensions is shear thinning (viscosity decreases as shear rate increases) over most of the shear rate range of interest for ceramic processing. The typical suspension viscosity as a function of shear rate is shown schematically in Figure 5.2 for different particle volume fractions. For noninteracting particles or repulsive particles, shear thinning occurs because Brownian motion randomizes particle arrangement at low shear rates. As shear rate increases, particles tend to align in the flow direction to produce preferred flow structures, which minimize hydrodynamic interactions resulting in reduced viscosity as flow rate increases. At very high shear rates, and volume fractions near maximum packing, particles become jammed and viscosity increases dramatically in a phenomenon known as shear thickening. Smaller particle sizes tend to increase viscosity of both repulsive and, especially, attractive particle networks primarily because the number of particle interactions per unit volume increases with decreasing particle size. Well-dispersed suspensions of particles with repulsive interactions produce lower viscosities (at any volume fraction) than attractive particle networks. This is simply because attractive particle interactions create an additional bonding force that must be overcome before particles can rearrange and flow. As such, well-dispersed suspensions at the highest volume fraction that is pourable are the desirable conditions for suspensions for ceramic processing.

Figure 5.2. Schematic representation of the influence of volume fraction on the viscosity of suspensions as a function of shear rate. At low shear rate, Brownian motion dominates producing high-viscosity randomized structures. At high shear rates, particles line up in preferred flow structures and viscosity decreases.

The final volume fraction (or packing) of particles during consolidation by pressure depends on the applied pressure and suspension response to applied pressure [11, 13] (Fig. 5.3). The suspension response to consolidation pressure is different for well-dispersed suspensions and attractive particle networks. Well-dispersed suspensions typically pack to near-maximum packing fraction, and density is insensitive to applied pressure. On the other hand, attractive particle networks result in lower final densities (at a particular pressure compared to dispersed suspensions), and density depends strongly on applied pressure. Pressure sensitivity (or lack thereof) is important because pressure gradients exist in complex-shaped dies during consolidation. These pressure gradients lead to density gradients in the case of attractive particle suspensions, which produce inhomogeneous green bodies. Such green bodies shrink nonuniformly during densification, tend to warp, and develop stresses, which lead to cracking and lack of shape control. Dry powder systems have no mechanism for developing repulsion between particles, so dry pressed components are particularly susceptible to green body density gradients, sintering warpage, and cracking.

Figure 5.3. Volume fraction of consolidated green body as a function of applied pressure for a well-dispersed suspension and attractive particle networks.

One of the most important reasons for using the colloidal processing approach is that it enables the production of ceramic materials that are more reliable because of the reduced number and size of flaws in the final component [9, 30]. Soft agglomerates can be broken down by combination of physical action (mixing, milling, etc.) and chemical action (creating repulsion between particles) using the colloidal approach. Hard agglomerates and inclusions can be removed by filtration or sedimentation of the well-dispersed suspension. Removal of these heterogeneities results in more uniform and flaw-free green bodies. Once sintered, components produced by colloidal processing will have improved strength and reliability.

5.3 Near-Net-Shape Colloidal Processing Techniques

Near-net-shape (NNS) processing techniques are able to produce green (and sintered) pieces that resemble the final geometry of the desired component. These methods minimize (or eliminate) expensive and costly diamond machining [6, 8].

NNS forming techniques can be classified as dry, plastic, and wet (colloidal) processing methods [31], depending on the water (solvent) content of the initial powder mixture (Fig. 5.4). The best-known example of dry NNS processing techniques is cold isostatic pressing (CIPping), where the powder is placed into a flexible mold. The mold sits inside an oil bath, which transmits hydrostatic pressure homogeneously to produce the green body. The main disadvantage is that the use of dry powder can cause problems associated with the presence of aggregates and low green density. Plastic NNS techniques include extrusion and the use of thermoplastic injection molding using binders that melt, such as paraffin wax, thermoplastic polymeric resins, and polymer mixtures for low-pressure injection molding processes. The main drawback is the removal of large amounts of polymers/binders (typically filling the entire interstitial space among particles), which can cause cracking and undesirable porosity. Paste homogeneity can also be a challenge, depending on the particle size of the powder.

Figure 5.4. Classification of green near-net-shaping ceramic processing techniques.

The colloidal NNS processing techniques involve the preparation of stable powder suspensions, as detailed in the previous section. The suspension is then cast into a mold with the desired geometry, and it is consolidated by different mechanisms, such as filtration (slip casting), gelation (gelcasting), freezing (freeze casting/ice templating), coagulation (direct coagulation casting), or evaporation (3D printing). The dispersion of the powder into a solvent offers the advantage of better homogeneity of the final material since aggregates are broken down. By controlling interparticle forces, packing of powder particles in the green body is more efficient, leading to a higher green density material [9, 10] and a more dense material after sintering.

Colloidal processing techniques have been used for several decades, but they are finding a second life in the application for the processing of materials that traditionally have not been prepared by these techniques, such as UHTCs. Nonoxide ceramics such as UHTCs are typically prepared by dry processing techniques in combination with HP [1, 2, 32] or, more recently, SPS [3–5], as shown in Figure 5.5. Their strong covalent bonding and low self-diffusion coefficients make the use of extremely high temperature and pressure necessary for densification. As a consequence, components are normally made in a very simple geometry (cylinders or tiles) that requires machining to achieve the final complex shape. The machining of such hard materials is time consuming and expensive. Therefore, the use of NNS techniques to produce green bodies in combination with PS is likely to be successful in producing UHTC components.

Figure 5.5. Dry processing route to prepare UHTC components. The main challenge associated with current technology for preparing UHTCs is the need for high temperature and pressure to densify the materials. This leads to the use of sintering aids, which reduces the service performance and limits shapes to very simple geometries.

Apart from the benefits of preparing complex shapes without the need for machining, colloidal processing offers other advantages as outlined in the previous section. Dry processing could lead to the introduction of potential defects in the material, such as impurities from grinding, agglomerates after drying the milled powder, and the need of sintering aids that could affect the final material, as explained in Figure 5.5. Through colloidal processing and control of interparticle forces in suspension (Fig. 5.6), better homogenization of particles within a suspension can be achieved along with the reduction of aggregates, both of which lead to higher particle packing in green bodies and minimization of the need for sintering aids. Enhanced particle packing in the green body leads to sintering at lower temperatures, removing the need for applying pressure.

Figure 5.6. Colloidal processing route to prepare UHTC components. In addition to removing flaws related to powder aggregates and improvement in the homogeneity of the sample, the control of the interparticle forces leads to higher particle packing that reduces the temperature for sintering and the need of pressure. In addition, near-net-shaping allows the manufacturing of UHTC complex shapes.

Most applications of UHTCs need large components of complex shape. Suitable colloidal processing techniques to be explored are summarized as follows:

- Slip casting. This is the oldest and simplest colloidal processing route. A ceramic suspension up to 50 vol% solids is cast into a porous mold (made of plaster of Paris or porous plastic) [31]. Capillary pressure exerted by the empty pores of the mold drives consolidation. The solvent is extracted from the slurry, while particles are deposited as a layer on the porous mold. The process continues until the cast body consolidates to the volume fraction determined by the applied capillary pressure and the compressibility of the sample, which depends upon the particle interaction [11, 33] (see Fig. 5.3). The body is then demolded and dried. This technique is normally recommended for components with uniform cross sections (thicknesses less than a centimeter or two) and for sizes no larger than a few hundred millimeters to ensure homogeneity. However, slip casting can be used for complex shaping, if the thickness of the plaster is sufficient to develop capillary suction pressure uniformly over the geometry. For complex shaping, a negative mold of the desired piece is made out of plaster. The slurry is cast in the cavity (Fig. 5.7a). Pressure filtration aids in the shaping of complex geometries, since it increases the particle packing density and the rate of filtration.

- Gelcasting. The technique was popularized by researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the 1990s [34–37] and has already become a classic approach for complex shape preparation in ceramic processing. Polymerization of a monomer in solution in a highly solid-loaded suspension leads to the preparation of green bodies with outstanding mechanical strength. Gelcast bodies can be unmolded, handled, and even green machined if needed, all within a shorter consolidation time than other techniques using less than 5 wt% gelcasting additives [38, 39]. Figure 5.7b summarizes the main steps of gelcasting. The monomer and crosslinkers are dissolved in the solution prior to powder addition. After the addition of initiator and catalyst (or activator), which trigger the polymerization reaction, the suspension is cast into the desired mold. This reaction initiates the formation of microgels between monomer and crosslinkers, which eventually join into a macrogel network that holds the particles in places, keeping the same homogeneity in the green body as in the suspension. Gelcasting is very attractive when used in combination with other processing techniques to prevent cracking during drying, as in tape casting [40–42], freeze casting [43–47], or hydrolysis-assisted solidification [48]. Gelcasting has also been combined with particle stabilized foams to make porous materials [49, 50].

- Freeze Casting. Freeze-drying is a very well-known technique for drying that was turned into a shaping technique [51–54]. The suspension is frozen inside the desired shape mold, and ice crystals formed by freezing the solvent are removed by sublimation (Fig. 5.7c). These ice crystals lock the particles in place, maintaining the homogeneity of the suspension through the green body and allowing for easy handling and unmolding the piece before the vacuum drying stage. After the sublimation, a packed (quickset) [54] or porous (ice templating) [55–57] green body is obtained, by adjusting the parameters of the method (freezing rate, solid content, cryoprotector addition) [58–60]. Setting times are very short, and drying times, depending on the size, make it an alternative to gelcasting. In most of situations, only 2 or 3 wt% dispersant is needed, minimizing the need for a binder burn-out step. Freeze casting has been used in combination with other techniques such as tape casting [61, 62], gelcasting, injection molding [54, 63], and electrophoresis [64], to aid drying and to create an extra level of porosity in materials.

- Tape casting. In contrast with the other techniques described so far, tape casting is used to produce flexible thin films that can be stacked together to produce a multilayer structure [31]. The suspension is poured into the reservoir of a doctor blade. Upon the movement of the carrier, the slurry is spread over the sheet with a thickness determined by the gap between the blade and the carrier sheet (final tapes of thickness ranging from 10 to 1000 μm). Solvent is removed by evaporation during drying. To prevent drying cracks and provide flexibility needed for handling, a number of polymeric additives, such as dispersant, binder, and plasticizer, are added to the suspension formulation. In addition, a mixture of solvents is recommended [65, 66]. This is the main reason why tape casting has been associated recently with gelcasting and freeze casting technologies.

Figure 5.7. Examples of colloidal shaping techniques. (a) Slip casting: the control of suspension rheology determines particle packing; the green body is formed by the removal of solvent by filtration; (b) Gelcasting: the green body strength is determined by the amount of monomer, crosslinker, initiator (and catalyst), and the solid content of the suspension; (c) Freeze casting: the green body microstructure is designed through control of ice growth, which is controlled by solid content, freezing temperature, freezing device, and cyoprotector addition.

5.3.1 Successful Processing of UHTCs Using Colloidal Routes

The earlier section described some of the most developed colloidal NNS techniques that could be put used for processing UHTCs. Several studies have been published pursuing the idea of using colloidal processing techniques for developing UHTCs. Huang et al. [16] prepared aqueous suspensions of ZrB2 for a freeze form extrusion fabrication rapid prototyping technique. Their ceramics reached relative densities of 96% by PS at 2000°C. Medri et al. [67] produced composites of ZrB2–SiC–Si3N4 by aqueous slip casting using a commercial dispersant. The bodies were sintered at 2150°C and produced relative densities of 98%. The preparation of flexible ZrB2 tapes was investigated using aqueous and organic suspensions of ZrB2 to produce a thicknesses of approximately 250–280 μm with a green tensile strength of 1.21 MPa [68, 69]. He et al. [70] developed aqueous gelcasting formulations using acrylamide and HEMA. Their ZrB2–SiC green bodies contained B4C and C as sintering aids that were sintered at 2100°C and 2 h to produce 98% relative density.

The versatility of colloidal processing techniques has led to the preparation of porous UHTCs, which opens a new range of applications where full density is not required. Landi et al. [71] have reported the preparation of ZrB2 materials with aligned porosity by ice templating (freeze casting) of aqueous suspensions. By tuning the parameters controlling the ice growth, materials with 60–70% porosity and pores ranging from 30 to 180 μm were prepared. Also, Medri et al. [72] produced macroporous materials with porosities up to 88% using natural and synthetic foams for replica procedures, and around 70% using ovalbumin as a surfactant for foam preparation. These authors used PS at 2100 and 2150°C, respectively, which ensured enough densification of the struts to reach strengths of 67 MPa in the case of ice templating. For sacrificial templating, higher porosity and larger pore size resulted in a strength of only 4 MPa.

Despite good results, a few issues are still holding back the application of these techniques to the UHTC community's needs. Some of the ongoing issues that need to be addressed are the following:

- Oxidation. The most important issue is the oxidation of UHTC powders. Oxidation affects the service conditions of UHTC components and can change performance from success to failure [2, 73]. The idea of putting UHTC particles into water for processing may not seem like the best way forward. However, powders supplied by manufacturers are sold in containers that allow contact with air. As a result, powders contain some oxygen impurities distributed as the corresponding oxide over the surfaces of the particles. Conventionally, the development of colloidal processing techniques has taken place using aqueous formulations. Nowadays, many different nonaqueous formulations are available, which may be more suitable for nonoxide ceramics. Compared to the as-supplied powders, no significant increase in oxygen content was measured for a common commercial ZrB2 powder upon soaking in water or cyclohexane after 2 days of immersion and subsequent drying at 80°C for another day in air [74]. Some other compounds like HfB2 or TaB2 may have stronger tendencies to oxidize [2, 75], but sintering aids like carbon are commonly used to reduce the oxygen content from the starting powders to levels necessary for densification. Colloidal processing is the best option to incorporate these additives homogeneously.

- Pressureless Sintering. If an NNS process is to be used, then densification needs to be done accordingly. PS can be used to densify materials that have very strong covalent bonds and low self-diffusion rates [2, 76]. PS is possible, if the driving force for densification is enhanced using sintering aids. Another way to improve densification is to improve particle packing or to reduce the starting particle size during synthesis [2, 76, 77] or by milling [3, 78–80].

- Particle size. Decreasing particle size is one of the main issues for colloidal processing. The term colloidal generally refers to particle sizes below 1 μm, yet commercially available ZrB2 powders have average particle sizes as high as approximately 20 μm. Above a few micrometers, gravity dominates particle behavior, and stable suspensions cannot be prepared due to sedimentation. Below 1 μm, interparticle forces and Brownian motion govern the behavior of particles in suspension. This enables creation of repulsive forces to overcome attractive forces and produce a stable suspension. Grinding and milling can be used to reduce particle size to appropriate values. Lee et al. [18] investigated milling of ZrB2 using a planetary mill with SiC balls and ethanol as dispersing medium. Due to the inherent properties of the powder, size was reduced from 2.3 µm initially to only 1.9 µm after milling, even after extensive milling times. More energetic milling procedures, such as attrition milling can be used, but impurities from grinding media [32] affect the purity of the powder and might compromise the final service conditions. Also grinding is an expensive operation. Synthesis of fine UHTC powders [77, 81] could address this problem although the amounts produced are typically too small to prepare large quantities of highly concentrated suspensions.

- Particle density and shape. Finally, the density and shape of particles are also a challenge. The smallest particle size available commercially is between 1 and 3 μm. Due to the higher densities of UHTCs, sedimentation forces in suspensions are a factor to consider. Since most of the small particle size powders available commercially have been produced by grinding, the shape of the particles is angular and irregular, far from the spherical shape that is preferred for high particle packing in green bodies to allow for PS.

Next, a case study is presented whereby colloidal processing and PS of ZrB2 demonstrate that colloidal processing is a viable option for the preparation of complex-shaped UHTC materials. In this study, bodies prepared by colloidal processing and PS are compared to those produced by dry processing and hot pressing without any sintering aids.

5.3.2 Case Study: Colloidal Processing and Pressureless Sintering of UHTCs

To investigate the feasibility of colloidal processing, zirconium diboride was selected as a reference material, since it is well studied and described in the literature. Slip casting and PS will be demonstrated to produce materials with near full density and able to survive extreme temperatures for a few minutes without melting or cracking. The details of this work are summarized here and presented in detail elsewhere [74].

5.3.2.1 Suspension Optimization through Rheological Study.

For this study, ZrB2 Grade B from H.C. Starck was used because it is used by most of the leading research groups. The powder is slightly aggregated, with a Dv50 of 2.3 μm, and has irregularly shaped particles. The oxygen content of the as-received powder was 0.90 wt%. Particles were suspended in water and an organic solvent (cyclohexane) for 2 days and dried at 80°C for 24 h. The oxygen content did not change from that initial value after suspension. However, to be conservative and because it produced lower-viscosity suspensions [17, 74], a nonaqueous formulation was selected to prepare the suspensions.

The first step was to study rheology to determine optimum suspension conditions. Suspensions of 20 vol% solids were prepared in cyclohexane using 1, 3, and 5 wt% of a commercial dispersant (Hypermer A70, Croda, Australia) with respect to the powder weight. This dispersant is a polymer comprised of hydroxyl and amino functional groups with a molecular weight of approximately 4.8 × 105 g/mol. The dispersant was dissolved in the solvent before adding the powder. Suspensions were sonicated for 2 min and rolled for homogenization for 6 h. Rheological behavior was studied using a rheometer (AR-G2, TA instruments) in parallel plate configuration with 40 mm diameter plates and a 700 μm gap, using shear rates from 10 to 1000 s−1. The viscosity as a function of shear rate behavior (Fig. 5.8) showed that the suspension with 1 wt% of dispersant exhibited shear-thinning behavior, indicating that it was not completely dispersed. With 3 wt% dispersant, the suspension was nearly Newtonian, indicating that it was well dispersed and stable. In contrast, 5 wt% dispersant was excessive, indicating that dispersant remained in solution and increased the viscosity of the suspension. Based on these observations, 3 wt% dispersant was selected as the optimum amount to prepare ZrB2 suspensions in cyclohexane. A high solid content suspension with a low-enough viscosity to fill the desired mold was desired for producing high green density. Suspensions with up to 50 vol% solids were prepared using 3 wt% dispersant. These suspensions had appropriate viscosity for slip casting [74].

Figure 5.8. Viscosity versus shear rate curves for ZrB2 suspensions prepared with different amounts of dispersant. The dispersant is Hypermer A70 and the solvent is cyclohexane. The volume fraction of solids is 50%.

Lee et al. [18] prepared aqueous ZrB2 suspensions up to 45 vol% by adjusting pH or adding PEI as a dispersant. Similarly, our group has also been working in aqueous formulations using different particle stabilization mechanisms [17]. The maximum solid contents and green densities were not as high for aqueous formulations as the ones achieved with the nonaqueous formulation because of stronger repulsion forces between particles in cyclohexane.

5.3.2.2 Green Body Formation.

Slip casting was selected as the shaping technique since it is simple and widely used for all types of materials. Also, it does not require the addition of any other reagent to consolidate the component, so the effect of particle packing on sintering could be studied directly.

Suspensions prepared using the optimized conditions described earlier were ball milled with WC media in a very gentle manner for 6 h. The goal was to ensure homogenization and a good quality suspension by breaking the aggregates of the initial powder, not to reduce primary particle size. The oxygen content in the powder increased during milling, as reported by Lee et al. [82]. In our case, the oxygen content was 1.25% after milling compared to 0.9 wt% initially. The final oxygen content in our samples at the end of the processing was below 1 wt% for all conditions studied [74].

Suspensions were cast into lubricated metallic rings of 50 mm diameter placed on top of plaster of Paris. Specimens were covered with plastic film to minimize evaporation during casting. After 24 h, they were unmolded. Slip cast disks (50 mm diameter, 10 mm height) had an average green density of 63% of the theoretical density. No cracks were observed, and the disks had enough strength to be handled and machined. Wang et al. [83] reported a green density of 53% after slip casting an aqueous ZrB2–SiC slurry of 45 vol%. The higher green density achieved in the present study was due to the stronger repulsion forces between particles in the nonaqueous solvent, which led suspensions with higher solid loadings. For comparison, the same powder was dry pressed into disks of similar dimensions applying a uniaxial load of 50 MPa. The green density of these disks was 48%. The ZrB2 particles in our slip cast bodies were nearly close packed due to the superior quality of the suspension (colloidal processing) and the removal of powder aggregates, as compared with the dry pressed powder, which can reach only low particle packing densities due to the Van der Waals attraction between the dry particles.

5.3.2.3 Sintering.

Disks produced by colloidal processing (and dry pressing) were sintered at 1900, 2000, and 2100°C in a graphite vacuum furnace set up to also run as a hot press. The dies, rams, and crucibles used were made out of graphite. Two sintering procedures were performed at each of these temperatures: PS and HP. For PS, disks were placed in a crucible outside the die, while disks for HP were loaded inside a die. The dwell time was 1 h at each temperature, and the applied pressure in the case of HP was 40 MPa, which was applied during the dwell at the maximum temperature. Heating and cooling ramps were 10°C/min up to 1500°C and 5°C/min above that temperature.

Slip cast disks required calcination stage at 400°C for 2 h in air prior to sintering to remove any remaining organic solvent and polymeric dispersant to protect the vacuum furnace. Calcination increased oxygen content to 3 wt%, but oxygen content was reduced below 0.5 wt% after vacuum sintering in the graphite furnace. The temperature for calcination was well below 700°C, which is the temperature above which significant oxidation of ZrB2 occurs [73, 84, 85].

Sintered samples did not show any signs of cracking for any of the selected temperatures or sintering procedures. Densification results are summarized in Figure 5.9. At 1900 and 2000°C, colloidal processing samples showed only signs of necking between particles when PS was selected, with densities around the 70%. However, at 2100°C, the disks reached 93% relative density. Although this value does not represent full densification, it is more than enough for a wide range of applications for UHTC materials [86]. This result is remarkable since the PS of borides to full density is very difficult, especially without any sintering aids as in this case. Grain coarsening can be faster than densification in borides, resulting in anisotropic growth and entrapped porosity [2]. Direct comparisons to other reported studies are difficult because many different starting powders have been used. However, in general, PS of ZrB2 powder from the same supplier as used in the present work resulted in 70% relative density, after attrition milling, cold pressing, CIPping, and sintering at 2100°C [87]. Reaching full density by PS is possible with the addition of SiC [83], MoSi2 [88], B4C [80], C [69], or WC [78]. In the case of colloidal processing, the enhanced densification is related to higher particle packing in the green body.

Figure 5.9. Sintered density of ZrB2 specimens as a function of processing route and sintering temperature. Densities of the green bodies for colloidal and dry processing routes were included as dashed horizontal lines for comparison.

Disks prepared by colloidal processing and HP achieved 98% relative density at 1900°C and full densification at 2000°C without any sintering aids. Densification of phase-pure ZrB2 by HP is normally achieved at temperatures of 2000°C or higher at pressures of 20–30 MPa or at lower temperatures but higher pressures. Monteverde et al. [89] reported a sintered density of 87% at 1900°C and 30 MPa under vacuum for similar powder as used in the present study, while Chamberlain et al. [32] obtained 98% relative density at 1900°C after 32 MPa and 45 min due to the incorporation of a significant amount of WC during milling. Reactive HP resulted in full densification of ZrB2 at lower temperatures such as 1890°C, but with the addition of 27% SiC [90]. In this context, results obtained using colloidal processing and HP in the present work have already matched and exceeded results previously reported for pure ZrB2, due to the improved homogeneity and green density of the samples.

Compared to dry pressing and sintering under the same conditions, colloidal processing led to higher densities in both PS and HP. Higher particle packing in the green body enhanced the densification due to the close contact between particles. The as-dry pressed pellet had a relative density of only 48%, versus 63% for the colloidal counterparts. Close contact between particles enhances densification process at lower temperatures, even in the absence of pressure or sintering aids. In addition, suspension formation removed aggregates from the as-received powder, enhancing the homogeneity of the green material and, therefore, the final components [10]. To corroborate the effect of particle packing on densification, samples prepared by dry pressing were CIPped at 400 MPa prior to sintering. The additional pressing of the dry particles in the green body led to an increase of 43% in sintered density after PS at 1900°C [74]. The same procedure applied to samples prepared by colloidal processing produced only an increase of 6% in the sintered density under the same conditions, because of the higher particle packing for the colloidal processing ones.

No signs of secondary phases were found by XRD or EDS [74]. The oxygen content of sintered samples was below 0.5 wt% in all cases, which is below the content measured for as-received powders. This demonstrated the suitability of wet processing for UHTCs without compromising their performance by oxidation. Since WC grinding media were used, WC impurities could have been acted as a sintering aid as reported in the literature. Chemical analysis revealed that the gentle milling with WC media left an impurity content of only 0.09 wt% W. This percentage was well below the values reported in the literature to aid the sintering of ZrB2. Therefore, improved particle packing was the only mechanism responsible for the enhanced densification.

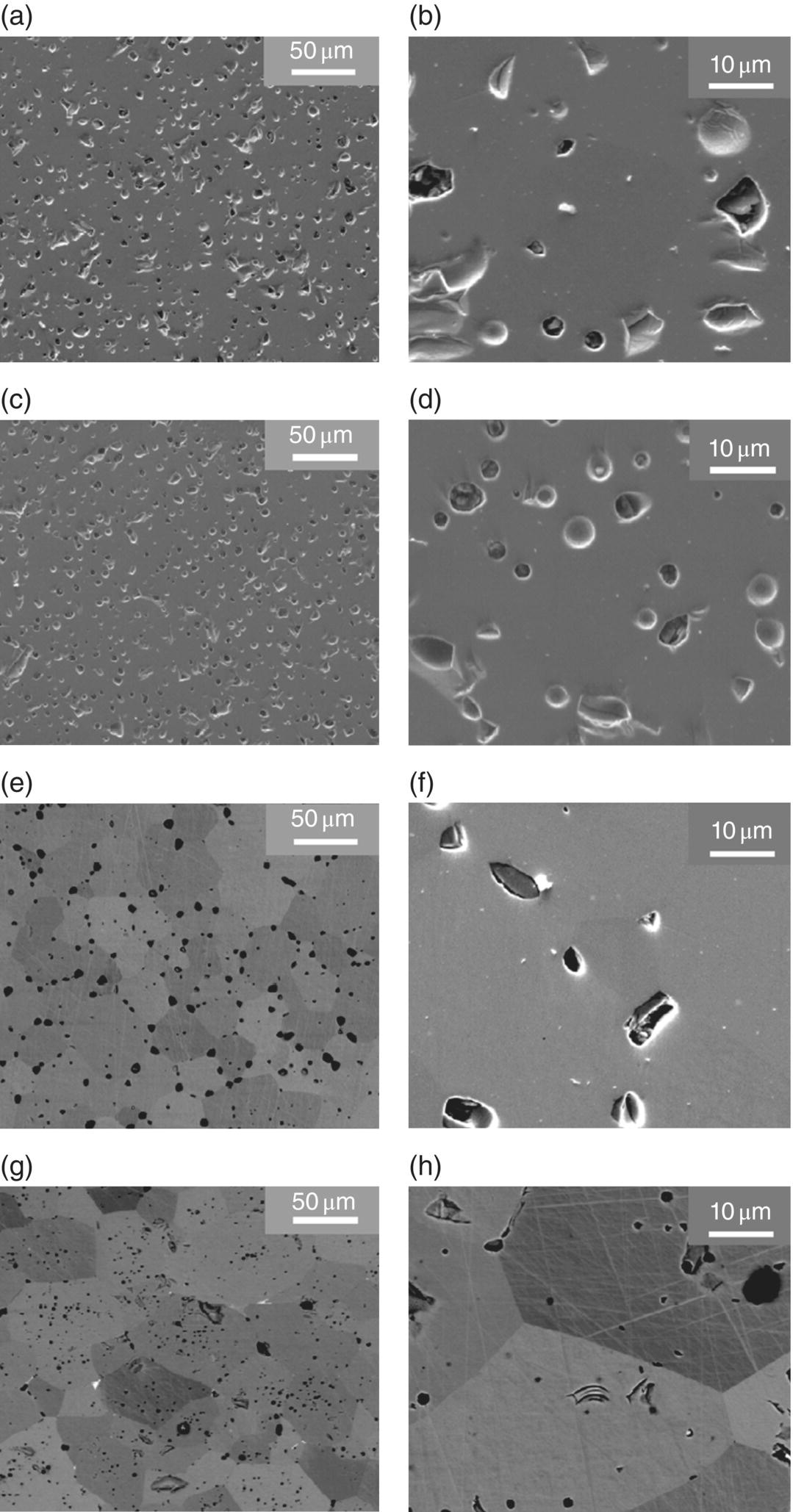

Microstructures of colloidally processing samples that were sintered at 2100°C are shown in Figure 5.10. Pores were observed along with some grain pullout from the polishing, but the microstructures were generally homogeneous and dense. Even though these samples were prepared without any additives or secondary phases, the relative density values and microstructures indicate that colloidal processing is a promising way to produce bulk UHTCs. The density and microstructure may be suitable for some applications where UHTCs are normally used [1, 86, 91, 92].

Figure 5.10. Microstructure of ZrB2 after sintering at 2100°C/1 h at different magnifications. (a and b) Colloidal processing and PS; (c and d) dry processing and PS; (e and f) colloidal processing and HP; (g and h) dry pressing and HP.

Linear and volume shrinkage were recorded during densification (Fig. 5.11). In the case of the colloidal processing samples, there is an increase in the shrinkage observed under pressureless conditions when increasing sintering temperature, in good agreement with the final density values. The dry pressed materials showed similar trends, only with higher shrinkages due to the lower particle packing in the green bodies (48% green density after dry pressing compared to 63% green density for colloidal processing). Linear shrinkage in the axial direction measured for HP materials seems much higher than for PS, but the difference was due to geometry. In HP, the diameter is constrained so all of the shrinkage occurs in the height compared to all dimensions for PS. The volumetric shrinkage during HP was only slightly greater than for disks prepared by colloidal processing, consistent with slightly higher sintered density of the HP materials. Nevertheless, the shrinkage values for the dry pressed materials were higher than for the specimens prepared by colloidal processing. This finding is relevant because even though the improved sintered densities for disks prepared by colloidal processing samples are only slightly higher for disks prepared by dry pressing, the reduced shrinkage of the colloidal processed materials translates into better tolerance and dimension control of the final object during manufacturing. This is especially significant in the case of complex-shaped components, where the dimension control represents a very costly and time-consuming step in their fabrication.

Figure 5.11. Shrinkage for ZrB2 samples as a function of the processing route and type and temperature of sintering. (The linear shrinkage for PS samples showed in the graph represents the average of height and diameter of the samples tested; in the case of the HP samples, the linear shrinkage represents the average of their height only, since the diameter is constrained by die dimension.)

5.3.2.4 Complex Shapes.

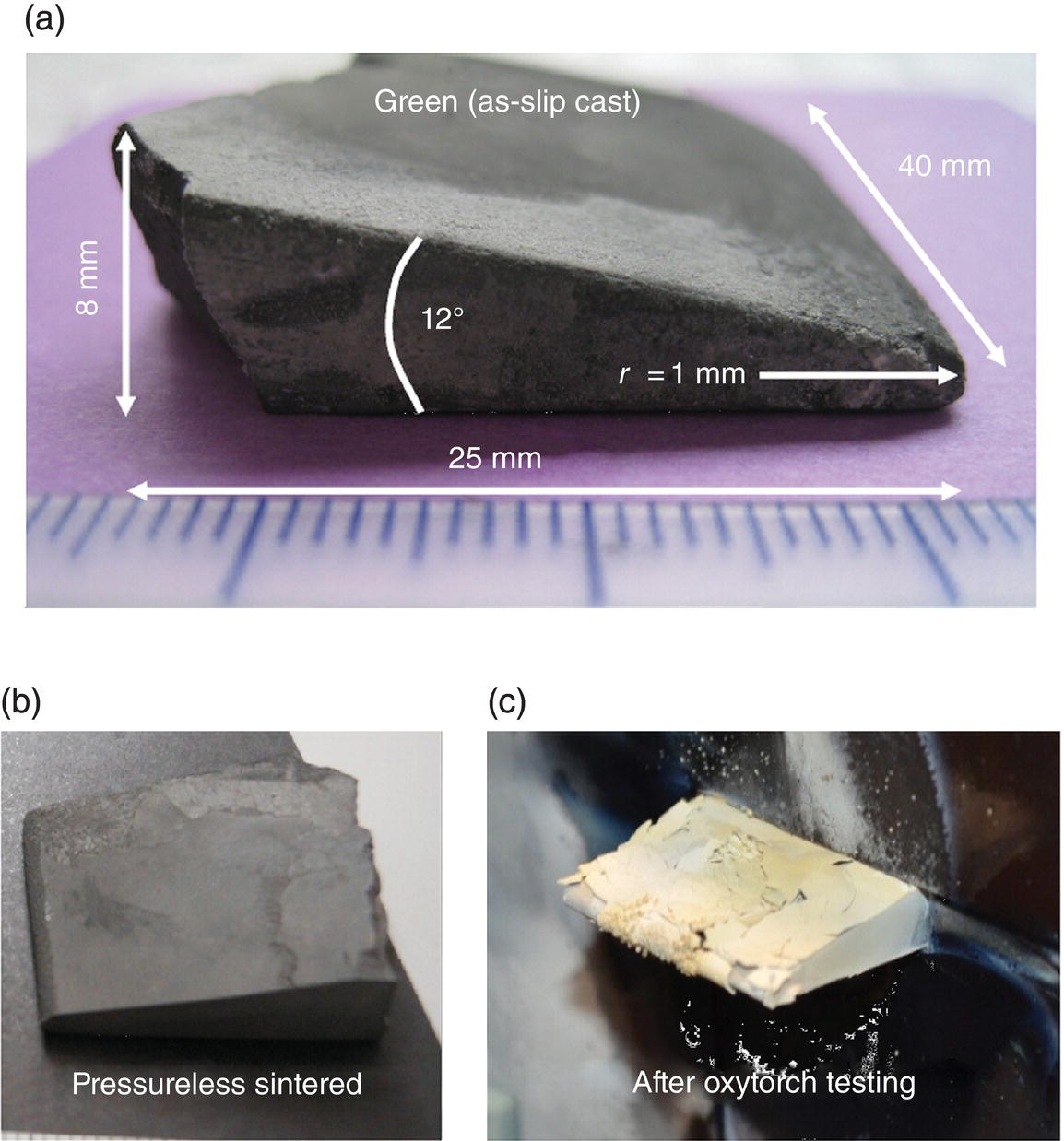

The systematic study described earlier confirms the viability of NNS of UHTCs by colloidal processing techniques. Using the same formulation and shaping technique, a notional leading edge was produced. A plastic mold was manufactured with the required geometry, and a negative plaster of Paris was made around it. The suspension was cast in the cavity, and after consolidation, the sample was unmolded and dried in an oven at 60°C overnight.

Figure 5.12a shows the as-molded green body, which resembles the desired leading-edge shape, including the sharp front angle. The green body had a smooth surface finish, without any additional machining. The green density was in good agreement with the values reported in the previous sections.

Figure 5.12. ZrB2 Leading edge. (a) Green body produced by slip casting as-unmolded; (b) after pressureless sintering at 2100°C/1 h; (c) after oxytorch testing.

Leading edges were densified by PS at 2100°C/1 h under vacuum. Samples did not crack upon sintering, as seen in Figure 5.12b. A relative density of 93% was recorded for samples sintered at 2100°C. Leading edges were then tested under an oxyacetylene torch (High Temperature Materials Evaluation Rig (HoMER), developed at DSTO Fishermans Bend, VIC, Australia). Wedges were subjected to a very high heat flux for 3 min, at temperatures above 3000°C, as read by the pyrometer. The flame was located at the center of the leading edge. The leading edges survived these extreme conditions without cracking or melting (Fig. 5.12c), although the surface was oxidized [93].

5.4 Summary, Recommendations, and Path Forward

Colloidal powder processing was an effective approach to manufacture complex-shaped UHTC components. Colloidal processing enabled enhanced reliability by controlling the interparticle forces between particles, removing flaws, and improving the particle packing in the green body. This resulted in a reduced temperature for densification and allowed for PS of as-shaped complex components.

Careful selection of solvent and processing additives is key to developing well-dispersed, low-viscosity, high-volume-fraction suspensions required for colloidal processing. To minimize the risk of oxidation of UHTC powders, nonaqueous formulations were selected. Further advances will be enabled by the development of polymers/dispersants that produce strong steric repulsion in nonaqueous solvents.

Fine powders (in the submicron-size range) are needed for colloidal processing to obtain all the benefits inherent to this approach in terms of green body homogeneity and improved reliability. In addition, fine powders also play a key role in the reduction of densification temperature due to their stronger driving force for densification.

Finally, it is expected that the development of nonaqueous gelcasting and freeze casting chemistries suitable for UHTCs will broaden the shaping capability of UHTC materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Defence Materials Technology Centre (DMTC) for funding and providing the support and framework to establish the collaboration to perform this work. This work was developed within the DMTC in collaboration with BAE Systems, University of Queensland, Swinburne University of Technology, Australian Nuclear Science Technology Organization (ANSTO), and Defence Science Technology Organization (DSTO). The authors would like also thank Dr. Chris Wood and Dr. Sonya Slater (Defence Science Technology Organization, DSTO, Fishermans Bend, VIC, Australia) for helping with oxytorch testing. Finally, the authors would like to especially thank Prof. Fahrenholtz for the invitation to contribute to this book.

References

- 1. Levine SR, Opila EJ, Halbig MC, Kiser JD, Singh M, Salem JA. Evaluation of Ultra-High temperature ceramics for aeropropulsion use. J Eur Ceram Soc 2002;22:2757–2767.

- 2. Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE, Talmy IG, Zaykoski JA. Refractory diborides of zirconium and hafnium. J Am Ceram Soc 2007;90 (5):1347–1364.

- 3. Medri V, Monteverde F, Balbo A, Bellosi A. Comparison of ZrB2-ZrC-SiC composites fabricated by spark plasma sintering and hot-pressing. Adv Eng Mater 2005;7 (3):159–163.

- 4. Melendez-Martınez JJ, Dominguez-Rodrıguez A, Monteverde F, Melandri C, de Portu G. Characterisation and high temperature mechanical properties of zirconium boride-based materials. J Eur Ceram Soc 2002;22:2543–2549.

- 5. Snyder A, Quach D, Groza JR, Fisher T, Hodson S, Stanciu LA. Spark plasma sintering of ZrB2–SiC–ZrC Ultra-High temperature ceramics at 1800°C. Mater Sci Eng A 2011;528:6079–6082.

- 6. Sigmund WM, Bell NS, Bergstrom L. Novel powder-processing methods for advanced ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc 2000;83 (7):1557–74.

- 7. Tallon C, Franks GV. Recent trends in shape forming from colloidal processing: a review. J Ceram Soc Jpn 2011;119 (1387):147–160.

- 8. Lewis JA. Colloidal processing of ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc 2000;83 (10):2341–2359.

- 9. Lange FF. Colloidal processing of powder for reliable ceramics. Curr Opin Solid State Mater Sci 1998;3 (5):496–500.

- 10. Lange FF. Powder processing science and technology for increased reliability. J Am Ceram Soc 1989;72 (1):3–15.

- 11. Franks GV, Lange FF. Plastic-to-brittle transition of saturated, Alumina Powder Compacts. J Am Ceram Soc 1996;79 (12):3161–3168.

- 12. Hunter RJ. Foundations of Colloid Science. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford Press; 2001.

- 13. Franks GV. Colloids and fine particles. In: Rhodes M, editor. Introduction to Particle Technology. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2008. p 117–152.

- 14. Israelachvili JN. Intermolecular and Surface Forces. 2nd ed. San Diego (CA): Academic Press; 1992.

- 15. Komulski M. Surface Charge and Points of Zero Charge. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2009.

- 16. Huang T, Hilmas GE, Fahrenholtz WG, Leu MC. Dispersion of zirconium diboride in an aqueous, high solid paste. Int J Appl Ceram Technol 2007;4 (5):470–479.

- 17. Leo S, Tallon C, Franks GV. Comparison of aqueous and non-aqueous colloidal processing of difficult-to-densify ceramics. Part I: suspension rheology. J Am Ceram Soc 2013. (In press, 2014).

- 18. Lee S-H, Sakka Y, Kagawa Y. Dispersion behavior of ZrB2 powder in aqueous solution. J Am Ceram Soc. 2007;90 (11):3455–3459.

- 19. He R, Zhang X, Han W, Hu P, Hong C. Effects of solids loading on microstructure and mechanical properties of HfB2–20 vol.% MoSi2 Ultra High temperature ceramic composites through aqueous gelcasting route. Mater Design 2013;47:35–40.

- 20. Zhang J-X, Jiang D-L, Tan S-H, Gui L-H, Ruan M-L. Aqueous processing of titanium carbide green sheets. J Am Ceram Soc 2001;84 (11):2537–2541.

- 21. Xiong J, Xiong S, Guo Z, Yang M, Chen J, Fan H. Ultrasonic dispersion of nano TiC powders aided by tween 80 addition. Ceram Int 2012;38:1815–1821.

- 22. Laarz E, Carlsson M, Vivien B, Johnsson M, Nygren M, Bergstrom L. Colloidal processing of Al2O3-based composites reinforced with TiN and TiC particulates, whiskers and nanoparticles. J Eur Ceram Soc 2001;21:1027–1035.

- 23. Zhang J, Duan L, Jiang D, Lin Q, Iwasa M. Dispersion of TiN in aqueous media. J Colloid Interface Sci 2005;286:209–215.

- 24. Wasche R, Steinborn G. Influence of the sispersants in gelcasting of nanosized TiN. J Eur Ceram Soc 1997;17:421–426.

- 25. Shih C-J, Hon M-H. Electrokinetic and rheological properties of aqueous TiN suspensions with ammonium salt of poly(methacrylic acid). J Eur Ceram Soc 1999;19:2773–2780.

- 26. Napper DH. Polymeric Stabilization of Colloidal Dispersions. New York: Academic Press; 1984.

- 27. Lamer VK, Healy TW. Adsorption-flocculation reactions of macromolecules at solid-liquid interface. Rev Pure Appl Chem 1963;13:112–133.

- 28. Barnes HA, Hutton JF, Walters K. An Introduction to Rheology. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1989. Rheology Series, 3.

- 29. Pugh RJ, Bergstrom L. Rheology of concentrated suspensions. In: Surface and Colloid Chemistry in Advanced Ceramic Processing, Surfactant Science Series. New York: Dekker; 1994. p 193–239.

- 30. Pujari VK, Tracey DM, Foley MR, Paille NI, Pelletier PJ, Sales LC, Wilkens CA, Yeckley RL. Reliable ceramics for advanced heat engines. J Am Ceram Soc 1995;74 (4):86–90.

- 31. Reed JS. Principles of Ceramic Processing. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1995.

- 32. Chamberlain AL, Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE, Ellerby DT. High-strength zirconium diboride-based ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc 2004;87 (6):1170–1172.

- 33. Stickland AD, Teo H-E, Franks GV and Scales PJ. Compressive strength and capillary pressure: competing properties of particulate suspensions that determine the onset of desaturation. Drying Technol 2013. DOI: 10.1080/07373937.2014.915218.

- 34. Janney MA, Omatete OO, Walls CA, Nunn SD, Ogle RJ, Westmoreland G. Development of low-toxicity gelcasting systems. J Am Ceram Soc 1998;81 (3):581–591.

- 35. Omatete OO, Janney MA, Nunn SD. Gelcasting: from laboratory development toward industrial production. J Eur Ceram Soc 1997;17 (2–3):407–413.

- 36. Omatete OO, Janney MA, Strehlow RA. Gelcasting—a new ceramic forming process. J Am Ceram Soc 1991;70 (10):1641.

- 37. Young AC, Omatete OO, Janney MA, Menchhofer PA. Gelcasting of alumina. J Am Ceram Soc 1991;74 (3):612–618.

- 38. Chabert F, Dunstan DE, Franks GV. Cross-linked polyvinyl alcohol as a binder for gelcasting and green machining. J Am Ceram Soc 2008;91 (10):3138–3146.

- 39. Tallon C, Moreno R, Nieto MI, Jach D, Rokicki G, Szafran M. Gelcasting performance of alumina aqueous suspensions with glycerol monoacrylate: a new low-toxicity acrylic monomer. J Am Ceram Soc 2007;90 (5):1386–1393.

- 40. J. Besida, D. E. Dunstan, J. Fawcett, C. Henderson, S. A. Khoo and G. V. Franks, Novel aqueous tape casting process. 107th Annual Meeting of the American Ceramic Society. Baltimore (MD); 2006.

- 41. Santanach-Carreras E, Chabert F, Dunstan DE, Franks GV. Avoiding mud cracks during drying of thin films from aqueous colloidal suspensions. J Colloid Interface Sci 2007;313:160–168.

- 42. Shanti NO, Hovis DB, Seitz ME, Montgomery JK, Baskin DM, Faber KT. Ceramic laminates by gelcasting. Int J Appl Ceram Technol 2009;6 (5):593–606.

- 43. Lee JP, Lee KH, Song HK. Manufacture of biodegradable packaging foams from agar by freeze-drying. J Mater Sci 1997;32 (21):5825–5832.

- 44. Weber K, Tamandl G. Porous Al2O3-ceramics with uniform capillaries. Cfi-Ceram Forum Int 1998;75 (8):22–24.

- 45. Chen RF, Wang CA, Huang Y, Ma LG, Lin WY. Ceramics with special porous structures fabricated by freeze-gelcasting: using tert-butyl alcohol as a template. J Am Ceram Soc 2007;90 (11):3478–3484.

- 46. Wu HH, Li DC, Chen XJ, Sun B, Xu DY. Rapid casting of turbine blades with abnormal film cooling holes using integral ceramic casting molds. Int J Adv Manufact Technol 2010;50 (1–4):13–19.

- 47. Fukushima M, Nakata M, Yoshizawa Y. Fabrication and properties of ultra highly porous cordierite with oriented micrometer-sized cylindrical pores by gelation and freezing method. J Ceram Soc Jpn 2008;116 (1360):1322–1325.

- 48. Ganesh I, Sundararajan G, Olhero SM, Torres PMC, Ferreira JMF. A novel colloidal processing route to alumina ceramics. Ceram Int 2010;36 (4):1357–1364.

- 49. Chuanuwatanakul C, Tallon C, Dunstan DE, Franks GV. Controlling the microstructure of ceramic particle stabilized foams: influence of contact angle and particle aggregation. Soft Matter 2011;7:11464–11474.

- 50. Liu W, Xu J, Wang Y, Xu H, Xi X, Yang J. Processing and properties of porous PZT ceramics from particle-stabilized foams via gel casting. J Am Ceram Soc 2013;96 (6):1827–1831.

- 51. Rey L, Pirie NW, Whitman WE, Kurti N. Freezing and freeze-drying [and Discussion]. Proc R Soc Lond Biol Sci 1975;191 (1102):9–19.

- 52. Flosdorf EW. Freeze-Drying. Drying by Sublimation. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation; 1949.

- 53. Kwiatkowski A, Reszka K, Szymanski A. Preparation of corundum and steatite ceramics by the freeze-drying method. Ceram Int 1982;6 (2):79–82.

- 54. Novich BE, Sundback CA, Adams RW. Quickset injection molding of high-performance ceramics. In: Cima MJ, editor. Ceramic Transactions, Forming Science and Technology for Ceramics. Westerville (OH): American Ceramic Society; 1992. p 157–164.

- 55. Deville S. Freeze-casting of porous ceramics: a review of current achievements and issues. Adv Eng Mater 2008;10 (3):155–169.

- 56. Dogan F, Sofie SW. Microstructural control of complex-shaped ceramics processed by freeze casting. Cfi-Ceram Forum Int 2002;79 (5):E35–E38.

- 57. Tallon C, Moreno R, Nieto MI. Shaping of porous alumina bodies by freeze casting. Adv Appl Ceram 2009;108 (5):307–313.

- 58. Araki K, Halloran JW. Porous ceramic bodies with interconnected pore channels by a novel freeze casting technique. J Am Ceram Soc 2005;88 (5):1108–1114.

- 59. Araki K, Halloran JW. Room-temperature freeze casting for ceramics with nonaqueous sublimable vehicles in the naphthalene-camphor eutectic system. J Am Ceram Soc 2004;87 (11):2014–2019.

- 60. Shanti NO, Araki K, Halloran JW. Particle redistribution during dendritic solidification of particle suspensions. J Am Ceram Soc 2006;89 (8):2444–2447.

- 61. Sofie SW. Fabrication of functionally graded and aligned porosity in thin ceramic substrates with the novel freeze-tape-casting process. J Am Ceram Soc 2007;90 (7):2024–2031.

- 62. Ren LL, Zeng YP, Jiang DL. Fabrication of gradient pore TiO2 sheets by a novel freeze-tape-casting process. J Am Ceram Soc 2007;90 (9):3001–3004.

- 63. Adams RW, Householder WB, Sundback CA. Applicability of quicksettm injection molding to intelligent processing of ceramics. Proceedings of the 15th Annual Conference on Composites and Advanced Ceramic Materials: Ceramic Engineering and Science Proceedings; January 13–16, 1991; Cocoa Beach (FL). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2008. p 2062–2071.

- 64. Zhang YM, Hu LY, Han JC. Preparation of a dense/porous BiLayered ceramic by applying an electric field during freeze casting. J Am Ceram Soc 2009;92 (8):1874–1876.

- 65. Moreno R. The role of slip additives in tape-casting technologies: part I-solvents and dispersants. J Am Ceram Soc 1992;71 (10):1521–1531.

- 66. Bohnleinmauss J, Sigmund W, Wegner G, Meyer WH, Hessel F, Seitz K, Roosen A. The function of polymers in the tape casting of alumina. Adv Mater 1992;4 (2):73–81.

- 67. Medri V, Capiani C, Gardini D. Slip casting of ZrB2–SiC composite aqueous suspensions. Adv Eng Mater 2010;12 (3):210–215.

- 68. Lu Z, Jiang D, Zhang J, Lin Q. Aqueous tape casting of zirconium diboride. J Am Ceram Soc 2009;92 (10):2212–2217.

- 69. Natividad SL, Marotto VR, Walker LS, Pham D, Pinc W, Corral EL. Tape casting thin, continuous, homogenous, and flexible tapes of ZrB2. J Am Ceram Soc 2011;94 (9):2749–2753.

- 70. He R, Zhang X, Hu P, Liu C, Han W. Aqueous gelcasting of ZrB2-SiC Ultra High temperature ceramics. Ceram Int 2012;38:5411–5418.

- 71. Landi E, Sciti D, Melandri C, Medri V. Ice templating of ZrB2 porous architectures. J Eur Ceram Soc 2013;33:1599–1607.

- 72. Medri V, Mazzocchi M, Bellosi A. ZrB2-based sponges and lightweight devices. Int J Appl Ceram Technol 2011;8 (4):815–823.

- 73. Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE. Oxidation of Ultra-High temperature transition metal diboride ceramics. International Materials Reviews 2012;57 (1):61–72.

- 74. Tallon C, Chavara D, Gillen A, Riley D, Edwards L, Moricca S, Franks GV. Colloidal processing of zirconium diboride Ultra-High temperature ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc 2013;96 (8):2374–2381.

- 75. Silvestroni L, Guicciardi S, Melandri C, Sciti D. TaB2-based ceramics: microstructure, mechanical properties and oxidation resistance. J Eur Ceram Soc 2012;32 (1):97–105.

- 76. Guo S-Q. Densification of ZrB2-based composites and their mechanical and physical properties: a review. J Eur Ceram Soc 2009;29:995–1011.

- 77. Zhang Y, Li RX, Jiang YS, Zhao B, Duan HP, Li JP, Feng ZH. Morphology evolution of ZrB2 nanoparticles synthesized by sol-gel method. J Solid State Chem 2011;184 (8):2047–2052.

- 78. Chamberlain AL, Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE. Pressureless sintering of zirconium diboride. J Am Ceram Soc 2006;89 (2):450–456.

- 79. Brochu M, Gaunt BD, Boyer L, Loehman RE. Pressureless reactive sintering of ZrB2 ceramic. J Eur Ceram Soc 2009;29:1493–1499.

- 80. Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE, Zhang SC, Zhu S. Pressureless sintering of zirconium diboride: particle size and additive effects. J Am Ceram Soc 2008;91 (5):1398–1404.

- 81. Jung EY, Kim JH, Jung SH, Choi SC. Synthesis of ZrB2 powders by carbothermal and borothermal reduction. J Alloys Compounds 2012;538:164–168.

- 82. Lee S-H, Sakka Y, Kagawa Y. Corrosion of ZrB2 powder during wet processing—analysis and control. J Am Ceram Soc 2008;91 (5):1715–1717.

- 83. Wang X-G, Liu J-X, Kan Y-M, Zhang G-J, Wang P-L. Slip casting and pressureless sintering of ZrB2-SiC ceramics. J Inorg Mater 2009;24 (4):831–835.

- 84. Fahrenholtz WG. The ZrB2 volatility diagram. J Am Ceram Soc 2005;88 (12):3509–3512.

- 85. Shappirio JR, Finnegan JJ, Lux RA, Fox DC. Resistivity, oxidation kinetics and diffusion barrier properties of thin film ZrB2, Thin Solid Films. I 1984;I9:23–30.

- 86. Glass DE. Physical challenges and limitations confronting the use of UHTCs on hypersonic vehicles. 17th AIAA Space Planes and Hypersonic Systems and Technology Conference; April 11–14, 2011; San Francisco (CA); 2011.

- 87. Zhu S, Fahrenholtz WG, Hilmas GE, Zhang SC. Pressureless sintering of carbon-coated zirconium diboride powders. Mater Sci Eng A 2007;459:167–171.

- 88. Sciti D, Monteverde F, Guicciardi S, Pezzotti G, Bellosi A. Microstructure and mechanical properties of ZrB2–MoSi2 ceramic composites produced by different sintering techniques. Mater Sci Eng A 2006;434:303–309.

- 89. Monteverde F, Guicciardi S, Bellosi A. Advances in microstructure and mechanical properties of zirconium diboride based ceramics. Mater Sci Eng A 2003;346:310–319.

- 90. Zimmermann JW, Hilmas GE, Fahrenholtz WG, Monteverde F, Bellosi A. Fabrication and properties of reactively hot-pressed ZrB2-SiC ceramics. J Eur Ceram Soc 2007;27:2729–2736.

- 91. Tallon C, Slater S, Gillen A, Wood C, Turner J. Ceramic materials for hypersonic applications. Mater Aust Mag 2011;45 (2):28–32.

- 92. Paul A, Jayaseelan DD, Venugopal S, Zapata-Solvas E, Binner J, Vaidhyanathan B, Heaton A, Brown P, Lee WE. UHTC composites for hypersonic applications. J Am Ceram Soc 2012;91 (1):22–28.

- 93. Tallon C, Slater S, Woods C, Antoniou R, Thornton J, Franks GV. High temperature testing of UHTC leading edges prepared by colloidal processing. J Am Ceram Soc 2014.