Chapter 63

Gabby’s car had given up from lack of use, so Nell drove Gabby to the station to catch the train back to London. She rushed off to buy Gabby magazines and papers, mineral water and chocolate. Ever the farmer’s wife, she imagined Gabby would starve to death between Penzance and London.

Gabby laughed. ‘Nell! I’m not on a train to Outer Mongolia!’

Nell snorted. ‘I know British Rail, or Great Western, whatever they call themselves. They either put on an empty buffet car or run out of everything before you reach Plymouth.’

Gabby hugged her and boarded the train. ‘Take care, Nell … I enjoyed our few days, pretending we were tourists.’

‘So did I, lovie. Don’t work too hard.’

‘I won’t. I’ll ring you …’

The train started to move slowly forward and Gabby leant out, said quickly, ‘I love you Nell!’ Then her head disappeared.

Nell was startled. She watched the long train snake out of the station and run along the track parallel to the sea, a little shimmer of heat haze hovering above the carriages. She and Gabby had never gone in for endearments or declarations of love. They had never needed to. She went slowly to her Land Rover where Shadow sat in the back panting sadly. She adored Gabby and hated it when she went.

Nell drove away from the station and out onto the dual carriageway. She intended to shop while she was there. She deliberately put away the sliver of unease, for she and Gabby had had such a happy week, getting back to normal after Josh and Marika had left.

Gabby felt sick. To her right the waves were grey and large, full of seaweed. A winter sea. The train stopped at signals and Gabby glanced left out of the opposite windows and glimpsed Nell’s Land Rover on the dual carriageway, with the shape of Shadow in the back.

She had the sudden eerie sensation of catching sight of a life she once shared from the disembodiment of a train. Seeing people blow along a sea wall walking dogs, heads bent against the wind, and knowing it could be her walking there and a stranger glimpsing her from a train window with a sense of recognition.

When Josh left, Gabby and Nell had decided they would have ‘outings’. Every day they would drive somewhere different. The Tate at St Ives. Barbara Hepworth and the myriad of small galleries and shops in the small coastal villages which were possible now that the hordes had left and schools were back.

They had sat by the sea and eaten leisurely lunches in Mousehole and Trelissik Garden. They had bought bulbs and plants for the front garden and taken long walks on different coasts. One day they had driven to the Lost Gardens of Heligan to see how the excavation of the Victorian Garden was progressing.

‘Isn’t it odd,’ Nell had asked, ‘how we just stopped going to places when Josh left home?’

‘I suppose we got busier, Nell. Took on more work and forgot to play.’

‘Elan used to call it Cornwallitis. This tendency we all have down here to get locked in and enervated by the weather and being so far from everything …’

‘Like agoraphobia; the distance just seems too great.’

‘Exactly.’

Gabby had picked up on Nell’s depression, so un-Nell-like that she made her promise to have a check-up to make sure it did not have a physical origin.

Gabby knew there was no way she could avoid hurting Nell and it made her feel desperate. The thought of losing her altogether … Gabby could not believe in a life without Nell somewhere in it.

There were notes all over the house from Mark and he had had a telephone line installed with an answer-phone. ‘I needed to know I could talk to you any time and mobile phones are extortionate.’

Gabby had collected flowers on the way home and she filled vases with them and roamed round the house feeling flat and lonely. Mark had booked an open ticket back because he couldn’t gauge how much time he would need.

She had one answer-message on the new phone. ‘I guess you’ll be home about five, sweetheart. Glad you’ve been having a good time with Nell. I’m not sure how long this is going to take. Inez has moved to New York, so I shall probably take an internal flight to see her. I want to talk to the kids first. My lot are great at Chinese whispers … I’ll ring you tonight … Oh, I nearly forgot, Gabriella. I’ve left something out for you on my desk. Directly under the photo of Lady Isabella pinned on the board. I think you’ll find it interesting.’

Gabby went and switched on the kettle, then walked over to Mark’s desk. He had photocopied two passages and made various notes for her. It was difficult to read as the original couldn’t have been clear after so many years and different hands had scrawled in the margins.

With the first entry, Mark had written on a separate piece of paper beside it: ‘John Bradbury checked this in the Parish records for me. Thomas Richard Magor was born on April 15th 1867 in the Parish of St Piran, but baptized in the parish of Mylor, near Falmouth, where presumably he grew up. But look at these photocopies, Gabriella. I found the entries for these two vessels at the Public Record Office in Kew. I then checked the Certificates of British Registry, plus Lloyds List information and merchant shipping movements at Guildhall Library. I was looking for something quite else!’

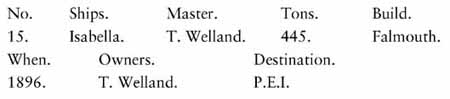

Gabby looked down at a register with a list of ship’s details arranged alphabetically. The year was 1883.

So the owners were Richard Magor, Isabella’s husband, and Thomas, their son. Gabby turned to the second document. The Morwenna was holed off Scilly when her load of wood shifted in a storm in 1884. Four of the crew died and the rest were rescued by lifeboat. They were Master S Budd, First Mate; L Wyatt, Second Mate; and Thomas Magor.

Richard’s son, now aged seventeen.

Gabby picked up the last document Mark had copied.

Gabby leant back. Goosebumps broke out all over her arms. Another ship named Isabella. Another Tom Welland. She looked up at the photo of the figurehead, stared at the sad and haunting face. Oh, Isabella, you and your Tom Welland must have had a child! Oh, God! What happened to you both? Your son was baptized with Richard’s name but he changed it later. Gabby brought her hands to her mouth.

I want to know. I want to know what dreadful thing happened to you, Isabella. Because it did, didn’t it? What made your son change his name suddenly? Gabby thought back quickly. Richard Magor must have been dead by then. Was it only then that Isabella’s son found out who his real father was? Oh, such a tiny glimpse of a story contained in that dry ledger.

She got up and paced the room. Oh, if only Mark was here. I want to talk to him about this. I long to know what really happened to Isabella and we’re never going to know, are we?

Gabby stared and stared at the face on the pin-board above her. Reached up and touched it with her finger. It was as if the air in the room shifted and deflected and took her to the sick moment of Isabella’s disgrace. This familiar face she had so lovingly restored. This face pulled up from the sea would haunt her forever, unless she knew.

She remembered the day in the cemetery and shivered. You want me to know, Isabella. You want me to know.

Mark had written: This perhaps explains why we could find so little reference to poor Isabella in the close-knit villages of Mylor and St Piran. I am so glad we found her and restored her to her rightful place, Gabriella.

Gabby looked out of the window and sighed. So, Isabella’s son Thomas changed his name and called another ship after his mother.