In the year 1955, Elizabeth Howes worked analytically with Emma Jung for several months.

I found Mrs. Jung the most integrated person in Zürich....

I found myself deeply moved by a woman who had so obviously found herself and her own authenticity in the midst of so many collective pressures. She was the wife of Carl Jung, which was certainly not an easy task. And she maintained – or rather, achieved – an individuality separate from his. She became a scholar in later years which culminated in her excellent book, The Legend of the Holy Grail. Also she became a wise and sensitive analyst, pointing simply and directly to what needed to be looked at. She was a joy to work with....

Mrs. Jung’s quiet, penetrating, active and participating attitude helped one always to know that one was working in a religious process where the unconscious was revealing – in even the slightest way – powers greater than the ego. But always I remember how she stressed the role of the ego in the development of consciousness. Mrs. Jung said to me, “There are egos and egos and egos. The problem is to find the right one.” To me, as I saw her, she had found hers and

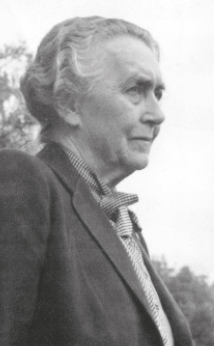

Emma Jung, 1955.

Wife, teacher, analyst, writer, mother of five, grandmother; Emma’s dignity and equanimity is apparent in this portrait in the year of her death.

had related it to the deeper archetypal powers making for wholeness.71

On May 6, Jung wrote to Victor White:

Dear Victor,

The serious illness of my wife has consumed all my spare time. She has undergone an operation so far successfully, but it has left her in a feeble state needing careful nursing for several weeks to come.72

In November, Australian author and teacher Rix Weaver had a meeting with Jung in his study in Küsnacht

Jung was called away ... and I waited quite awhile. When he returned there was a change. He told me the doctor had just called and that his dear wife wouldn’t recover. I offered to leave but he bade me stay. He then sat a little longer to speak. This time he said that life has to be lived fully. One has to live what one is, utilize one’s potential. He spoke of his wife’s life and its completeness, then added, “Death is a drawing together of two worlds, not an end. We are the bridge.”73

Five days later, on November 27, 1955, Emma Jung died.

Dear Neumann,

Deepest thanks for your heartfelt letters.... I am sorry that I can only set down these dry words, but the shock I have experienced is so great that I can neither concentrate nor recover my power of speech. I would have liked to tell the heart that you have opened to me in friendship that two days before the death of my wife I had what one can only call a great illumination which, like a flash of lightning, lit up a centuries-old secret that was embodied in her and had exerted an unfathomable influence on my life. I can only suppose that the illumination came from my wife, who was then mostly in a coma, and that the tremendous lighting up and release of insight had a retroactive effect upon her, and was one reason why she could die such a painless and royal death.

The quick and painless end – only five days between the final diagnosis and death – and this experience have been a great comfort to me. But the stillness and the audible silence about me, the empty air and the infinite distance are hard to bear.74

At the funeral, in a packed church in Küsnacht, Jung led in his family of five children and nineteen grandchildren.

Afterwards friends found him alone in his study, sobbing repeatedly, “She was a queen. She was a queen.”75

After the death of my wife ... I saw her in a dream which was like a vision. She stood at some distance from me, looking at me squarely. She was in her prime, perhaps about thirty, and wearing the dress which had been made for her many years before by my cousin the medium. It was perhaps the most beautiful thing she had ever

Jung at Bollingen, c. 1950s.

In times of stress, Jung found that carving in stone gave him “inner stability.”

I Ching diagram.

In his foreword to R. Wilheim’s translation of the I Ching, Jung wrote of the Chinese symbols as “readable” archetypes.

worn. Her expression was neither joyful nor sad, but, rather, objectively wise and understanding, without the slightest emotional reaction, as though she were beyond the mist of affects. I knew that it was not she, but a portrait she had made or commissioned for me. It contained the beginning of our relationship, the events of fifty-three years of marriage, and the end of her life also. Face to face with such wholeness one remains speechless, for it can scarcely be comprehended.76

Following a visit to his daughter Marianne, Jung wrote,

Dear Marianne,

Warmest thanks for your lovely letter which was a great joy. I am glad you weren’t bored with me. It was a joy to be together with you for a while....

Mama’s death has left a gap for me that cannot be filled. So it is good if you have something you want to carry out and can turn to when the emptiness spreads about you too menacingly. The stone I am working on gives me inner stability with its hardness and permanence and its meaning governs my thoughts.77

Laurens van der Post recorded a late conversation he had with Jung:

He told me toward the end of his life ... [he] was carving in stone ... some sort of memorial of what Emma Jung and Toni Wolff had brought to his life. On the stone for his wife he was cutting the Chinese symbols meaning “She was the foundation of my house.” On the stone intended for Toni Wolff he wanted to inscribe another Chinese character to the effect that she was the fragrance of the house.78