The Will to Live

For people sent left in the initial selection at Auschwitz station, survival was by no means guaranteed. They had been spared the immediate fate of the gas chambers, but to stay alive in this environment of slave labour and deprivation, so far removed from normality, would take extraordinary willpower, fortitude and luck.

Those considered fit enough to work were marched to one of the many camps that formed Auschwitz. Auschwitz I, the original concentration camp, was an old Polish army barracks that predominantly housed male prisoners. Birkenau, or Auschwitz II, was the women’s camp and also evolved into the main killing centre. Auschwitz III, Buna-Monowitz, was the location of the I.G. Farben industrial factory. There were also around forty sub-camps.

The new prisoners were herded into a building called the sauna, where the process of dehumanization began. All clothes, shoes, glasses and other possessions were forcibly removed and the naked prisoners showered under water that was invariably freezing or scalding. They were disinfected and shaved all over, an intentionally humiliating procedure. Everyone who entered Auschwitz as a labourer had a number crudely tattooed on their left forearm, by which they would be referred for the duration of their imprisonment.

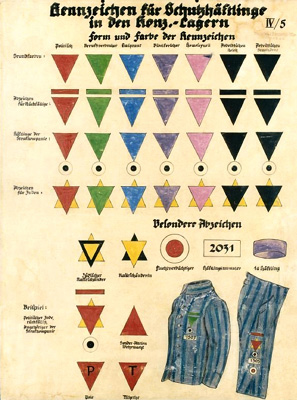

The assignment of numbers in place of names was a significant part of the dehumanization process wrought by the Nazis, as it stripped away a person’s identity and individuality. Likewise the removal of hair, though ostensibly to prevent disease, could render prisoners unrecognizable even to their kin and deprived people of their self-worth. Symbols were also used in the concentration camp system to reduce imprisoned enemies of the regime to categories: homosexuals were marked by pink triangles, Jehovah’s Witnesses by purple triangles and political convicts by red triangles.

Chart showing the symbols used to categorize concentration camp prisoners

Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1993-051-07 / CC-BY-SA

The daily routine and living conditions were intentionally, crushingly, demoralizing. Barracks designed to house fifty-two horses now became the sleeping quarters for over 700 humans. Three-tiered wooden bunks, which at best might be covered with a straw mattress or a thin blanket, often held more than eight or nine people tightly packed on each level. Every morning the prisoners scrambled out of these bunks for roll call (Zählappel), which normally started at around 4.00am. This was another form of selection, as many did not have the strength to stand unsupported for several hours as they were counted and recounted. They stood in rows of five until everyone, including those who had died in the night or during Zählappel, was accounted for. This routine was repeated at the end of each working day.

Bunk beds in an Auschwitz barracks

After roll call minimal food rations were distributed, normally consisting of an inch of hard black bread and tiny sips of a brown liquid purported to be coffee. Occasionally there would be a few mouthfuls of watery soup or a morsel of sausage. To own a bowl or a mug was vital if you were to receive your share and many came to possess such an item through a bartering process that was called, in camp language, ‘organizing’. By saving up bread rations to trade, by finding items such as cigarettes and handkerchiefs which another inmate might value, or by taking from the dead, prisoners could gradually supplement their meagre diets and clothe themselves more effectively.

As in the ghettos, conditions in Auschwitz were grossly insanitary and overcrowded. It was rumoured that typhus was carried in the water supply and lice and rats infested the whole area. Within weeks of arrival, people’s bodies rebelled. Scabies was an infectious skin condition that affected many prisoners and diarrhoea and dysentery were common. Wounds sustained through work or punishment did not heal readily and although there was a sick barracks, this was a perilous place to stay as frequent selections for the gas chambers were made among the ill prisoners.

All who were incarcerated in Auschwitz were faced with the horror of realizing that they had been brought to a centre where human beings were methodically exterminated. The perpetually smoking crematoria chimneys and the omnipresent smell of burning meat were apparent from the moment prisoners arrived, grim emblems of the fate that could befall anyone.

Maintaining the will to live in any of the Nazi camps often depended on mutual support and companionship, without which deterioration could be swift. Having someone to care for, who could reciprocate small kindnesses, meant there was an immediate, tangible reason to try to stay alive. Whole communities were annihilated in the gas chambers, but to have just one family member or friend still living gave people determination and hope. For those who believed, often correctly, that they had nobody left, it was sometimes easier to give up than to endure the gruelling environment and many took their own lives on the electrified barbed wire fences.

In camp jargon, prisoners close to death were called Muselmänner. This word described those who had devolved into barely living skeletons and shuffled slowly with vacant stares, with no means or motivation to recover their strength. For these people, the horrors of Auschwitz were too great to bear and they physically and mentally gave up the fight to survive. If they were not gassed, shot or beaten to death, they submitted to a slow demise in the camp’s mud.