10

Ambulatory Management of Childbirth Pelvic Floor Trauma

Khaled M.K. Ismail, Rasha Kamel, and Vladimir Kalis

Introduction

Annually, millions of women worldwide sustain trauma to the pelvic floor at the time of childbirth. A significant number of these women suffer short‐term and sometimes long‐term consequences, which can have a negative impact on both physical and emotional health, and also affect their quality of life. The burden of these complications is even greater when the age of the woman and the effect on her family is taken into account. In recent years, there has been a lot of focus on the prevention, assessment, and repair of childbirth‐related pelvic floor trauma. There has been a plethora of evidence‐based guidelines, quality improvement initiatives, and innovations and multidisciplinary training programmes devised to address these issues. Nevertheless, the focus has mainly been on intrapartum care with relatively less attention to the antenatal and postnatal periods.

There is wide global variation in maternity service provision and funding. Moreover, there are cultural differences that have an impact on several aspects of maternity care including shared norms, beliefs, and expectations. These factors will undoubtedly affect what services are being offered, how they are utilised, and what is being prioritised. Irrespective of the type or location of healthcare, postnatal services do not receive the same level of attention or funding as antenatal and intrapartum services. Furthermore, childbirth‐related pelvic‐floor trauma and its consequences do not receive the required level of attention because of the tendency to focus on pregnancy progress and foetal development. This, at least sometimes, translates to a significant number of women missing out on crucial information relating to current or previous childbirth pelvic floor trauma and how to mitigate the risk of complications in the short and long term. Although intrapartum management of pelvic‐floor trauma is considered a core skill of any birth attendant, the management of its consequences requires specialised training. Women's pelvic floor pathology encompasses a wide spectrum of functional, anatomical and neurological problems, which may be associated with symptoms of bowel, urinary, and/or sexual dysfunction. Care for women with pelvic‐floor trauma is, therefore, best delivered via a multidisciplinary approach.

Childbirth pelvic trauma and its complications can be addressed in the ambulatory care setting. This can include consultation, investigations, treatment, interventions, and sometimes rehabilitation services. We believe that this model of care should be utilised in the context of specialised postnatal clinics because it will ensure that women receive fast, effective, consistent, and evidence‐based management without added pressure on other maternity services. We see the ambulatory care setting as an interface between primary and secondary care, receiving referrals from family physicians, community midwives, as well as hospital referrals. If the healthcare system allows, we believe women should be able to self‐refer when plagued by a particular query or concern. In this chapter, we will cover the services and procedures that can be undertaken within an ambulatory service in relation to childbirth pelvic‐floor trauma.

Perineal Wound Complications

In women undergoing vaginal delivery about 85% are known to sustain some form of perineal injury. The short‐term sequelae of perineal injury include bleeding and pain, but may include wound complications such as infection, dehiscence and granulation tissue. Persistent pain after eight weeks postpartum occurs in about 22% of women and with about 20% experiencing dyspareunia.

Anal dysfunction such as faecal or flatus incontinence can occur with obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIs). In the long term, perineal trauma such as levator muscle avulsion has been postulated as risk factors for pelvic floor disorders such as pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence.

Perineal Wound Infection

A two‐iteration Delphi study of women who had previously sustained perineal trauma was undertaken to determine patient‐reported outcomes for perineal trauma. The quality‐improvement study demonstrated that the highest ranked outcome was fear of perineal wound infection and delay in wound healing.

There is growing evidence that the number of women reporting perineal wound dehiscence and infection in the community is increasing. A significant number of these wound breakdowns occur within the first two weeks of delivery. However, there are several issues that should be taken into account when discussing childbirth‐related perineal wound infections. These include:

- In many healthcare settings there are no systems to track wound infection and dehiscence in the community and this has led to the wide disparity of prevalence from 0.59 to 13.5%.

- There is lack of perineal‐wound validated screening tools that can be used in the community or primary care for early identification of infection.

- Disparity exists between clinically suspected and microbiologically confirmed perineal wound infection.

- Wide variation in the management of wound infection and dehiscence.

Perineal wound infection and dehiscence can have serious consequences on a woman's general health and quality of life. These problems include persistent pain and discomfort at the perineal wound site, urinary and bowel problems, and dyspareunia, as well as psychological and psychosexual issues from perceived or altered body image. The most serious complication that can arise is systemic sepsis. It is imperative, therefore, that women with suspected perineal infection are reviewed urgently. Women who have problems with their wound in the form of increasing pain, excessive or offensive discharge, pyrexia, feeling generally unwell, swelling of the wound, or evidence of wound dehiscence should have an urgent assessment.

There is a paucity of validated tools for the objective assessment of perineal wounds for the early detection and follow‐up of wound infection. Until a more specific tool is available, we recommend the use of the REEDA score (Table 10.1) for perineal wound assessment. The REEDA tool assesses Redness (R), Edema (E), Ecchymosis (bruising) (E), Discharge (D) and approximation of the perineal wound edges (A). Its scientific merit relies upon taking precise measurements and providing objective descriptive data to assess the condition of the wound over a period of time.

If a wound infection is suspected, microbiological swabs should be taken from the perineal wound area and the woman should be prescribed appropriate broad‐spectrum antibiotics. We recommend that the antibiotic regimen discussed and agreed upon with the local microbiology team is in line with unit policy. The prescribed antibiotics should be reviewed once the swab results are available. Further follow‐up appointments will depend on the severity of infection, presence of wound breakdown, and general maternal condition. In general, it will be appropriate for the woman to be seen in the clinic weekly for the first two to three weeks. With each visit, an objective assessment of the wound condition using REEDA score should be performed and documented. Once the infection is cleared and the wound has healed, it would be prudent to arrange a follow‐up visit after 8–12 weeks or even later, to check for any long‐term complications such as perineal pain or dyspareunia.

Table 10.1 The REEDA score.

| Score | Redness | Edema | Ecchymosis | Discharge | Approximation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | None | None | None | None | Closed |

| 1 | Mild Less than 0.5 cm from each side of the wound edges |

Mild Less than 1 cm from each side of the wound edges |

Mild Less than 1 cm from each side of the wound edges |

Serum | Skin separation 3 mm or less |

| 2 | Moderate 0.5 cm to 1 cm from each side of the wound edges |

Moderate 1 to 2 cm from each side of the wound edges |

Moderate 1 to 2 cm from each side of the wound edges |

Serosanguinous | Skin and subcutaneous fat separation |

| 3 | Severe More than 1 cm from each side of the wound edges |

Severe More than 2 cm from each side of the wound edges |

Severe More than 2 cm from each side of the wound edges |

Purulent | Skin and subcutaneous fat and fascial layer separation |

Total |

|||||

| Overall score = + |

Dehiscence

Wound dehiscence is frequently preceded by or occurs in association with wound infection. This breakdown can involve the whole wound or only part of it. There is a wide variation in how a wound dehiscence is managed. Some favour expectant management; however, it can take up to 12–16 weeks for the wound to heal by secondary intention. The evidence for the management of such a complication is currently weak; nevertheless, it favours wound re‐suturing 24–48 hours after appropriate antibiotic cover. The latter policy seems to be associated with a reduction in the time required for wound healing and improved satisfaction with the outcome after the wound has healed. In view of the negative impact of expectant management, we strongly recommend that women are counselled and given a choice about both management options so that they can make an informed choice. Re‐suturing a dehisced wound will require anaesthesia for wound debridement and can be done as a day‐care procedure under antibiotic cover in the absence of sepsis. An ambulatory clinic can identify complications, initiate treatment, provide counselling about management options, and follow up women after re‐suturing and those opting for expectant management.

Granulation Tissue

When a wound heals by secondary intention, granulation tissue may form to bridge the gap between the wound edges. Less commonly, it can also form after wound healing by primary intention. Women tend to be referred with what is thought to be a skin tag, an area that is friable or bleeds easily when touched, or a persistent and excessive discharge. In almost all cases, the excessive granulation tissue can be chemically cauterised in the outpatient setting using silver nitrate. Sometimes more than one treatment is required.

Superficial Dyspareunia Following Childbirth

It is reported that 17–23% of women continue to experience superficial dyspareunia at three months after delivery and 10–14% at 12 months. In some studies, rates of 62 and 31% were reported for three and six months postnatal respectively. In view of the risk of such a problem triggering more complex psychosexual disorders, it is important that they are dealt with promptly, sensitively, and efficiently. The ambulatory set‐up provides a suitable environment for this because women would be seen away from both obstetrics and gynaecology outpatient environments where they can be given more time and also have their problem assessed by a specialist.

The cause of superficial dyspareunia following childbirth can be physical and/or psychological. One of the physical causes of superficial dyspareunia following perineal trauma or episiotomy is scar tissue at the introitus, particularly over the area of the fourchette (posterior commissure). This can result from excessive scar tissue formation or poor anatomical repair of the perineal tear. Typically, a thin band of scar tissue or a web of skin at the introitus can be seen on examination by parting the labia and slightly stretching the area of the fourchette. This web of skin or scar tissue will be very tender to touch on digital examination and during intercourse. Some women complain that it splits and bleeds during penetration. It is not uncommon for this problem to be missed on general inspection of the labia.

Conservative approaches, including the use of vaginal dilators, vibrators, and perineal massage have been reported to provide relief of symptoms in a minority of patients. The majority of women, however, will require a procedure to release or remove this area of scarring. A modified Fenton's procedure can be performed as an outpatient procedure under local anaesthesia. One of the main benefits of undertaking the procedure under local anaesthesia is the conscious pain mapping prior to surgery. The procedure follows the same concept as Fenton's, which involves a vertical incision, dissection of underlying scar tissue, followed by closure of the incision horizontally (Table 10.2). It is important to avoid overzealous dissection and the recommendation is to use fine fast absorbing polyglactin suture and a continuous technique for closure in two layers, to reduce the tension on the skin stitches.

Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injuries

Third‐ and fourth‐degree perineal tears are collectively known as OASIs. This section will not cover the prevention, identification, or primary repair of OASIs but rather the management of women who have had this type of injury, in an ambulatory centre.

OASI Primary Repair and Follow‐Up

It is good clinical practice that women who sustain OASIs have a follow‐up appointment in a dedicated clinic at 12 weeks postnatally. During that visit we recommend the following:

- Take a detailed bowel history exploring the timing of the symptoms in relation to the OASIs. Using a bowel control, symptom‐specific questionnaire can be of value in assessing the degree of anal dysfunction.

- Use the faecal incontinence severity index (FISI) and Faecal Incontinence Quality of Life assessment tools to improve the objective assessment (see Table 10.3).

Table 10.2 Steps of a modified Fenton procedure.

Source: Modified from Chandru et al. (2010).

Band of scar tissue at the introitus part on parting the labia and very tender to touch

Vertical incision

Dissection of underlying scar tissue

Repaired across in two layers using continuous 3/0 polyglactin suture

Table 10.3 Faecal incontinence severity index.

Never Rarely Sometimes Usually Always a) Solid 0 1 2 3 4 b) Liquid 0 1 2 3 4 c) Gas 0 1 2 3 4 d) Wears pad 0 1 2 3 4 e) Lifestyle alteration 0 1 2 3 4 - Perform a clinical examination including checking the neurological function of sacral segments, such as the anal wink reflex.

- Assess the women's ability to perform correct and effective pelvic floor muscle training and discuss physiotherapy referral if required.

- Give the woman the opportunity to ask questions about her birth and trauma.

- Perform an endoanal ultrasound of the anal sphincter complex ± manometry.

- Discuss the short and long‐term implications of the trauma and counsel her about mode of delivery for future births However, this will have to be reviewed with any future pregnancy if there is any change in her bowel symptoms.

Further investigations, follow‐up, and multidisciplinary involvement will need to be tailored to the woman's needs.

Ultrasonography

Assessment of the internal and external anal sphincter by means of ultrasonography can be performed using an endoanal ultrasound (EAUS) or exo‐anally using trans perineal ultrasound scanning (TPUS). Colorectal surgeons traditionally use endoanal ultrasonography, however, the availability of high‐resolution volume sonography and tomographic ultrasound has made the diagnostic accuracy of trans perineal scanning in identifying anal sphincter pathology very comparable to that of endoanal ultrasound. TPUS also has the added advantages of cost saving, patient acceptability, and the avoidance of internal stretch of the anal canal and sphincters. With volume sonography, a volume is acquired with subsequent multiplanar and tomographic ultrasound imaging (TUI) sub‐analysis. For TUI, an anal sphincter defect is defined as a defect of 30° or greater in the circumference of the external anal sphincter in at least two of three slices for EAUS or four of six slices for TPUS. Comparative studies of EAUS and 3D TPUS suggest good agreement. A step‐by‐step practical guide on how to perform and interpret a TPUS for the assessment of the anal sphincters is listed in Box 10.1.

Anorectal Manometry

Anorectal manometry is used for the functional assessment of the anal canal and rectum. The anal sphincter pressures, rectal sensation, and anorectal reflexes are measured using a number of pressure sensors mounted on a narrow balloon‐tipped catheter inserted into the rectum. The parameters measured include:

- Anal canal resting pressure, which is generated by the resting tone of the IAS (normal range 61–163 cm H2O).

- Voluntary anal squeeze pressure generated by the external anal sphincter contraction (normal range 50–181 cm H2O).

- Involuntary anal squeeze pressure generated by asking the woman to cough to assess the external anal sphincter reflex (normal range 50–100 cm H2O).

Mode of Birth in Pregnancies Subsequent to OASIs

Following OASIs, women should be counselled about the mode of birth in subsequent pregnancies. Current guidelines recommend that women who have neither bowel symptoms subsequent to their OASIs nor significant abnormality on ultrasonographic evaluation of the sphincters or anorectal manometry be offered a vaginal birth. There are fairly good levels of evidence to support this recommendation. In contrast, women who do not fulfil the aforementioned criteria should be offered an elective caesarean section in subsequent births, but the evidence in support of the latter recommendation is not robust.

In women who attend for follow up after OASIs and undergo anatomical and functional assessment of the anorectal complex, there is no reason that this discussion cannot be initiated at that time. This approach will give women the opportunity to plan future pregnancies based on clinical information specific to them. Although ultrasound findings should not change overtime, the woman's symptoms or anorectal manometry might. We, therefore, recommend that a detailed assessment of the woman's bowel function should be undertaken again during the antenatal period of any future pregnancy and the mode of birth re‐discussed before a final recommendation is made. Women who did not have investigations performed during the follow‐up of their OASIs will need to have these performed during the antenatal period of their subsequent pregnancy. An ambulatory set‐up provides a one‐stop setting where investigations, results, and counselling can take place with the aim to improve efficiency and reduce a woman's anxiety.

Levator Ani Muscle Avulsion

Pelvic floor disorders, urinary incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse have been identified as important long‐term complications of perineal trauma. Apart from the neurological damage and stretching of pelvic floor muscles in vaginal deliveries, the avulsion injury sustained to pelvic floor muscles is attributed as an important causative factor in pelvic floor disorders.

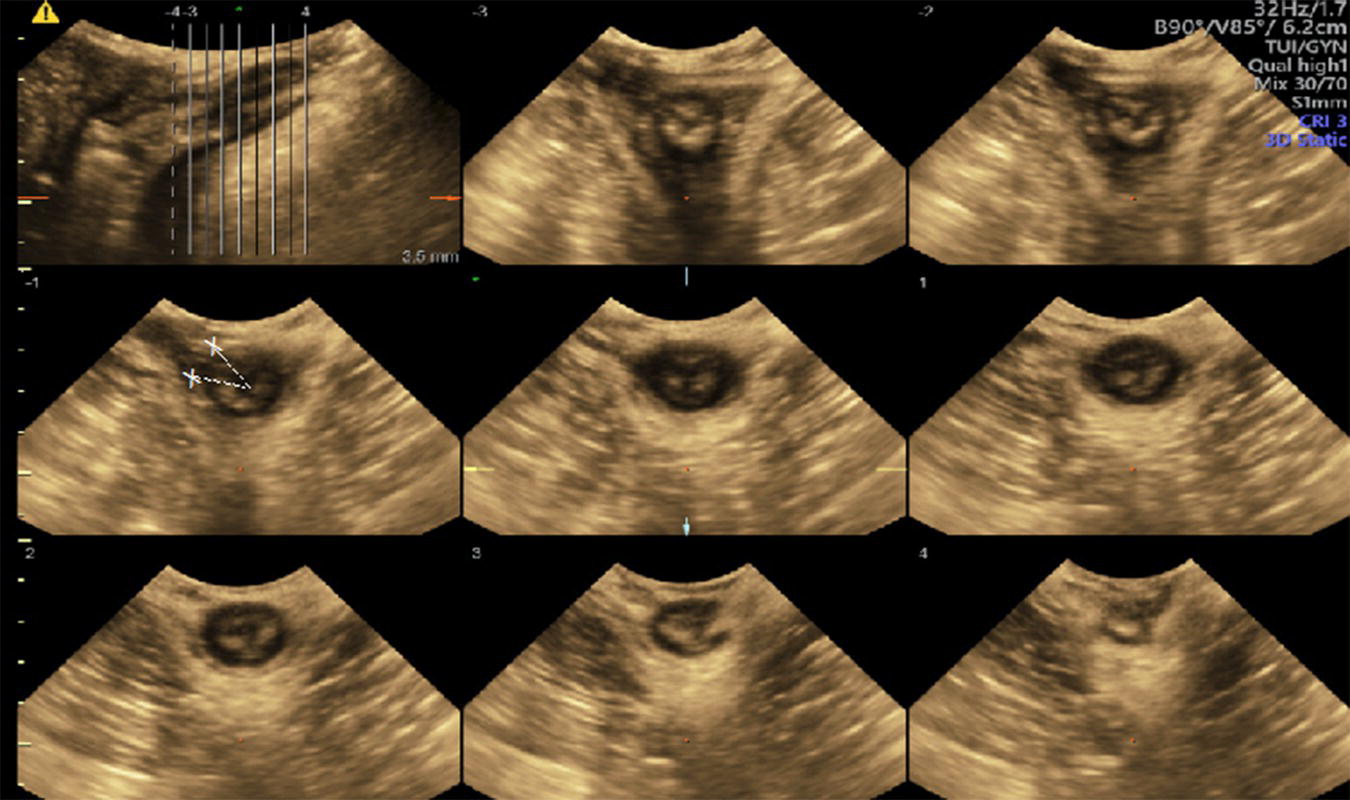

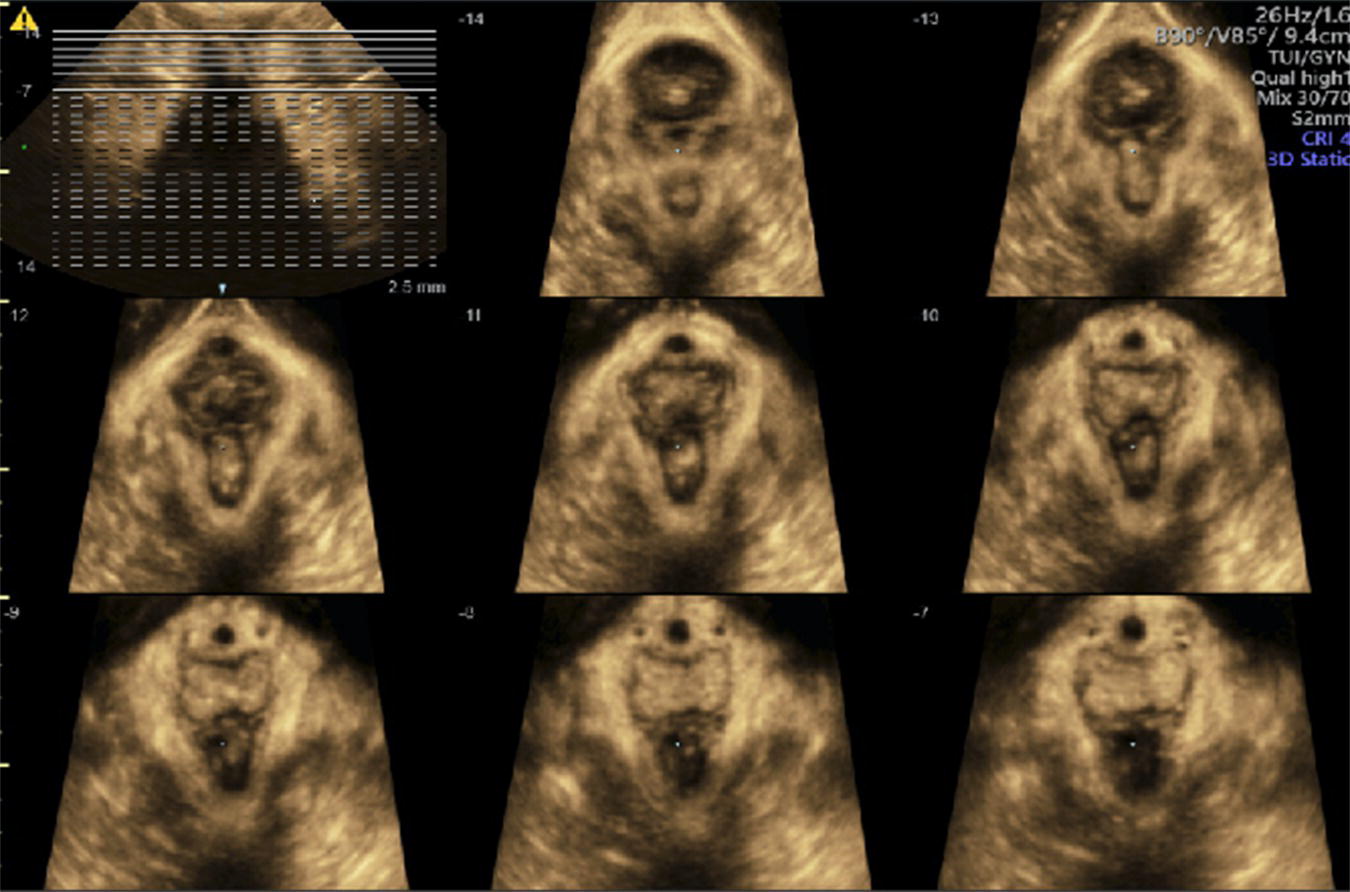

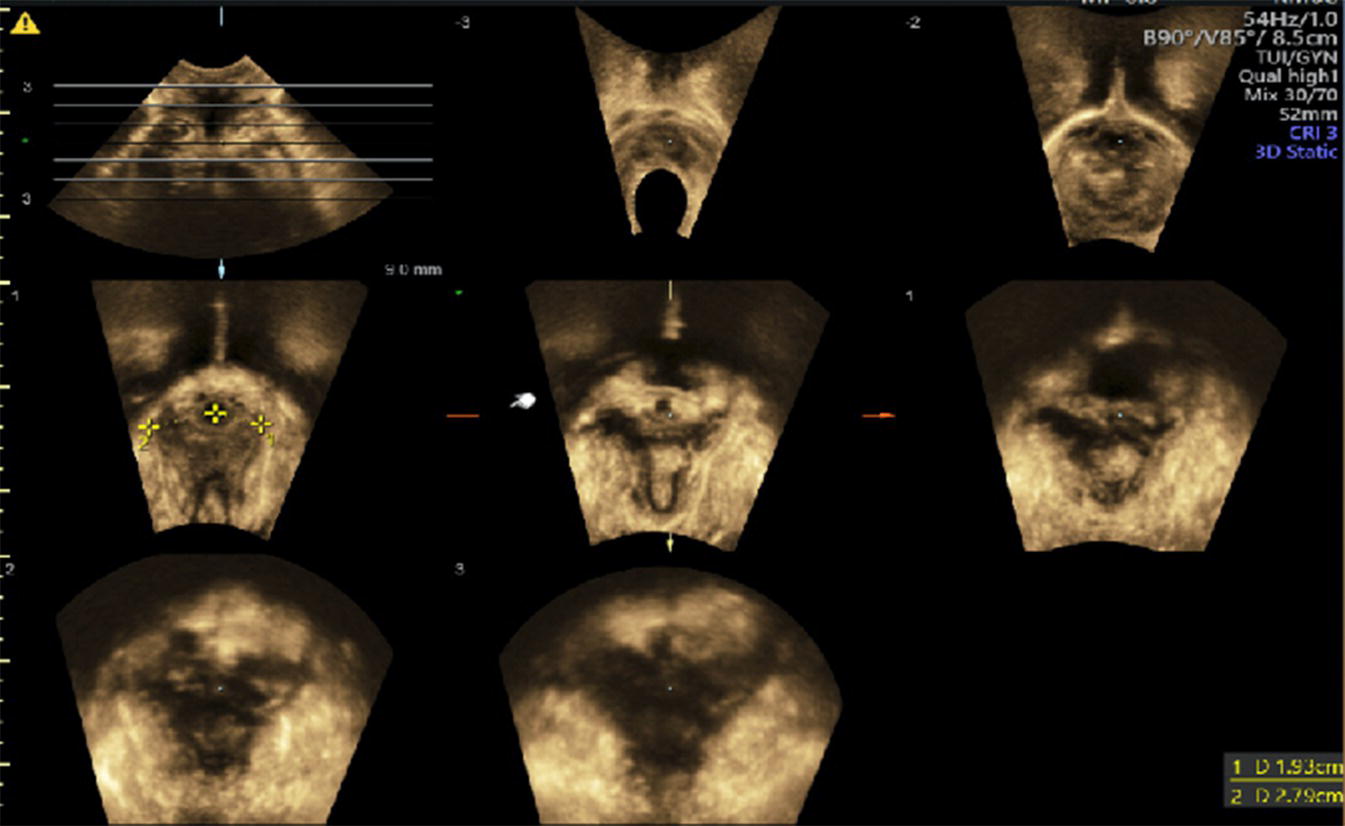

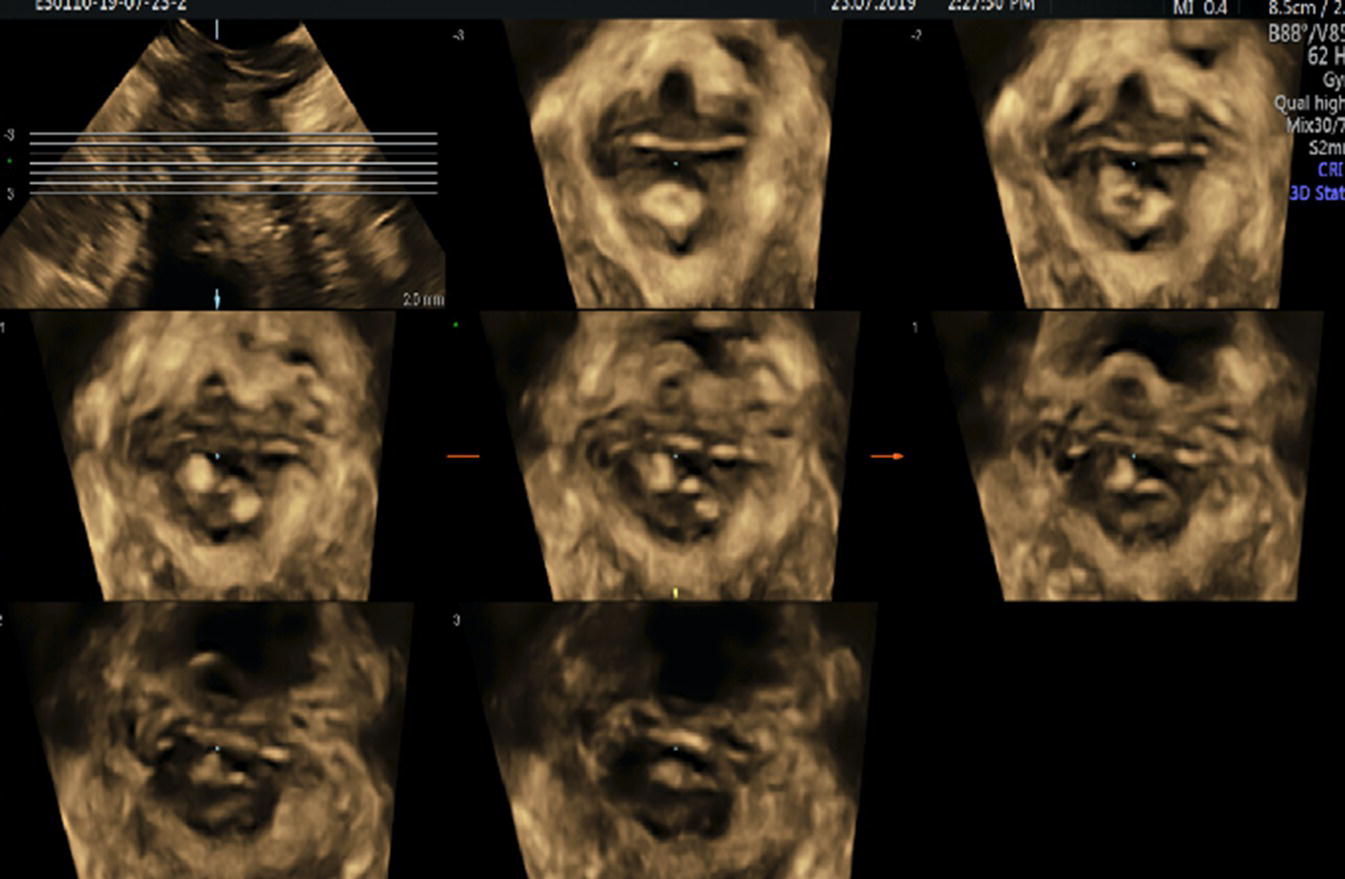

Levator avulsion (LA) is the detachment of the pubovisceral muscle (PVM) component of the levator ani muscle from its insertion into the pubic bone. There is wide variation in the reported incidence of avulsion injury, which ranges from 13 to 36% after the first birth. The risk is significantly higher following operative vaginal birth especially with forceps. The difference in incidence is also contributed to by the variation in the method and timing of diagnosis. LA can be complete or partial and either unilateral or bilateral. Although partial avulsions are more likely to improve over time, they are still associated with subjective and objective pelvic floor dysfunction. Palpation of the site of insertion of the PVM is sometimes recommended as a method of screening for LA, however, the diagnostic accuracy of this method relies on the skill of the examiner and the presence of an intact side to act as a reference. Nonetheless, natural variation in PVM insertions is a real limitation to this technique. Therefore, accurate diagnosis relies on imaging techniques, mainly in the form of 3D ultrasonography or magnetic‐resonance imaging (MRI). For this reason, the diagnosis tends to be made a long time after birth. Good agreement between MRI and 3D TPUS has been reported with the ultrasound assessment being more reproducible, more convenient and more cost‐effective. The TPUS assessment for LA should be undertaken upon pelvic muscle contraction for better tissue enhancement and with a volume acquisition angle of at least 70°. On TUI sub‐analysis, LA is diagnosed when abnormal insertion is detected in three central slices or with a levator‐urethral‐gap (LUG) of >2.5 cm (Figures 10.1–10.4).

Although LA is known to increase a woman's long‐term risk of prolapse, there is currently no policy or recommendation for routine screening even in high‐risk women (e.g., after forceps deliveries or births complicated by OASIs). If there is a clinical need to confirm or refute the possibility of an LA, the presence of clinical expertise and an imaging facility within the ambulatory clinic is beneficial. At present, there are no effective surgical interventions for the repair of LA. There does, however, seem to be potential benefits in structured antenatal pelvic floor muscle exercises and alteration of avoidable risk factors such as obesity and constipation to reduce the individual woman's likelihood of developing significant pelvic floor disorders in the future.

Figure 10.1 TUI sub‐analysis of a 3D volume TPUS of a normally attached levator ani upon muscle contraction.

Figure 10.2 3D Axial view of a unilateral right sided levator avulsion.

Figure 10.3 TUI sub‐analysis of a 3D volume TPUS of a unilateral right sided levator avulsion with a LUG of 27.9 mm.

Figure 10.4 TUI sub‐analysis of a 3D volume TPUS showing bilateral Levator avulsion.

Figure 10.5 TUI sub‐analysis of a 3D volume TPUS showing an EAS defect.

Conclusion

Perineal trauma after childbirth can pose significant physical and psychological morbidity. A dedicated centre in the ambulatory set‐up, which provides consultation alongside imaging modalities and the ability to perform day‐care surgical procedures, will be the way forward in caring for these women.

Further Reading

- Chandru, S., Nafee, T., Ismail, K. et al. (2010). Evaluation of Modified Fenton procedure for persistent superficial dyspareunia following childbirth. Gynecol Surg 7: 245–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10397‐009‐0501‐7.

- Dietz, H.P. (2018). Exoanal imaging of the anal sphincters. J. Ultrasound Med. 37: 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.14246.

- Dudley, L.M., Kettle, C., and Ismail, K.M. (2013). Secondary suturing compared to non‐suturing for broken down perineal wounds following childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.: 9. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008977.pub2.

- Hiller, L., Radley, S., Mann, C.H. et al. (2002). Development and validation of a questionnaire for the assessment of bowel and lower urinary tract symptoms in women. BJOG An Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 109: 413–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471‐0528.2002.01147.x.

- Ismail, K.M.K., Kettle, C., Macdonald, S.E. et al. (2013). Perineal assessment and repair longitudinal study (PEARLS): a matched‐pair cluster randomized trial. BMC Med 11 https://doi.org/10.1186/1741‐7015‐11‐209.

- Laine, K., Rotvold, W., and Staff AC (2013). Are obstetric anal sphincter ruptures preventable?‐ large and consistent rupture rate variations between the Nordic countries and between delivery units in Norway. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 92: 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12024.

- Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (2015). The Management of Third‐ and Fouth‐Degree Perineal Tears: green‐top Guideline No. 29. R. Coll. Obstet. Gynaecol. 29: 1–11.