From the time she had started to look at paintings, the recent German art Anni liked the most had been by the Blue Rider group. But while she admired Macke, Marc, and Jawlensky (she showed no interest when I asked about Gabriele Münter and Marianne von Werefkin, dismissing them, it seemed, because they were women), she had always considered Klee and Kandinsky “the two great ones of the group.” Their presence at the Bauhaus thrilled her. “When Klee proposed taking a line for a walk, I took thread everywhere it could go.”

One of the reasons for Klee’s great impact was the way he built totalities out of components. Anni felt that she was uniquely receptive to this approach because of its applicability to weaving. She also admired the way he made use of the fundamental tools of the drawing and painting processes. Rather than disguise the brushstrokes in his attempts to conjure the surfaces of houses or boats or faces, he had the imprint the brush made on paper or canvas serve as a compositional element. In drawings, he used the scribbling of the pencil, or the little points he created with the point of his pen, to build entire organisms. Anni was attracted to the ways that Klee celebrated rather than disguised the physicality of art and technique.

“The technical makes you focus on what you are trying to do and forget introspection,” Anni maintained. She enjoyed what she called “the stimulation of limitations” and applied Robert Frost’s views on free verse to her deliberate subjugation to the dictates of the loom and thread. She quoted Frost saying that to work without preestablished laws is like playing tennis with the net down. Similarly, she followed Klee’s self-imposed restriction to uniform components, declaring that “the work of any artist, if it’s in music or writing or painting or whatever, is that of reduction of elements.”

THERE WAS, HOWEVER, no pretending that Klee was accessible personally. At the Weimar Bauhaus, when Anni had initially tried to get into one of his classes, she was refused—with the advice that she develop her own work further. Anni recalled what happened when Klee became form master of the weaving workshop:

Klee was our god, and my specific god, but he was remote as a god usually is. Although it sounds like blasphemy, I didn’t think he was actually a teacher who could help those who were in their early stages trying to find their way. I remember his standing in front of a blackboard with us eight or ten students sitting behind him, and I can’t remember that he turned around once to make contact with us students. He had this strange remoteness; besides, I really didn’t understand what he was talking about. It was a disappointment, because I admired his work tremendously—and still think of him as the great genius.

Anni took a fiendish delight in saying this to me while Josef was in the house with us but safely out of earshot in his studio. He would have become enraged with jealousy had he heard her put anyone else above him in the ranking of great artists.

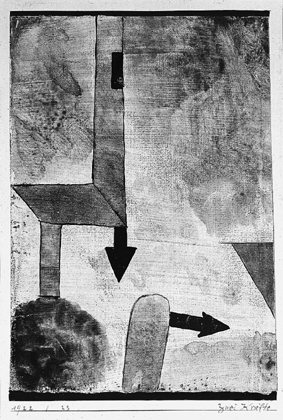

Paul Klee, Zwei Kräfte [Two Forces], 1922–23. Annelise Fleischmann marveled at the spontaneous exhibitions of Klee’s watercolors, when the artist tacked them on the corridor walls of the Weimar Bauhaus. One of the rare students who could afford to buy One, she opted for a particularly mysterious image—although there was much about the transaction that left her unsatisfied.

Ise Bienert persuaded Klee to exhibit his watercolors on the corridor walls of the school. These occasional shows were “the great events of my time at the Bauhaus,” recalled Anni. But, as was almost always the case, even with Klee her memories were of things working out less than perfectly. She asked him if she could buy a watercolor with “valuta”—money in a stable currency, a gift to her from an uncle. Klee was delighted, and showed her a portfolio of twenty recent works. “I’m still puzzled by this: that I hardly liked any of them,” she said to me wistfully. “I thought he was not offering me his top works, they were all not quite in balance, but I chose one because I thought, ‘If I don’t do it today, tomorrow will be too late.’” Years later, when she and Josef were struggling financially in America, she would sell the water-color through Josef’s dealer Sidney Janis; if it had never been her favorite work, at least it helped financially.

Even if she later disparaged the watercolor one can see why Armi picked it. It is one of those Klees with a background that is undisguisedly paint applied to paper, with seemingly random brushwork almost like a child’s finger painting, the paint so thin and watery that every grain of the textured paper is visible. On top of that surface that, by unabashedly presenting the processes and materials of art, resembles a sea of microscopic dots, there are forms that are more mysterious the longer we look at them. One is made of two bands joined at a right angle, like half of a mitered picture frame constructed out of wide strips of wood. That inanimate object stands on another band, which rests on a cloudlike blob. At the mitered corner, there is a large arrow pointing down; three quarters of the way up, there is a small dark rectangle.

The other image on Anni’s Klee is a form that resembles both a stone tablet standing at an angle and a ghost with a sheet over its head. Near the cap of this form with a domelike top, another large arrow, longer than the first one but not as dark, points off to the right. The only additional element is a cut triangle, like a ship’s stern cut off by the right-hand side of the painting.

Everything suggests something, yet nothing is clear. There is a distinct narrative in these bold arrows, a sense of movement in many directions, but the reason for the hurry, or the purpose of the helter-skelter dashing, or their differences in proportion and tonality, are unknowable. What is without question, though, is that while life is enigmatic, the processes of making art have an irresistible fascination, and creativity enables one to celebrate, rather than shun, indecipherability.

THE COMPONENT OF DISAPPOINTMENT—or, alternatively, of disapproval—was inevitable in all of Anni’s memories. When Klee was form master of the weaving workshop and the students hung their wall hangings for him, “he came in and judged all the various pieces, mostly smaller than my big hangings there, and he passed my pieces every time. My heart sank lower and lower. I thought, ‘What on earth have I done?’” The complete lack of reaction from her hero was so devastating that, when she told me about it half a century later, she readily relived her misery.

Socially, the Alberses’ age group was rarely included with the more established generation; they felt they “did not count.” The one time Anni and Josef were invited to Klee’s home, when they were all neighbors at the masters’ houses in Dessau, Klee played a record of Haydn for them. When Anni passed Klee on the street, she always was so afraid of interrupting his reverie that she did not even try to say hello; nor did he.

But that sense of his remoteness is what had inspired her fellow weavers to conceive of the miraculous delivery of his presents for his fiftieth birthday, the event that proved, somehow, that in spite of all the vulnerability, all the challenges, the Bauhaus was a place unlike anywhere else. For there were no boundaries on human imagination.